Clinical and aetiological heterogeneity have impeded our understanding of depression. Improving our effectiveness in treating depression may require more precise matching of treatments to specific characteristics of patients. Atypical and melancholic depression are increasingly being distinguished in depression studies, in recognition of the fact that the large heterogeneity in major depressive disorder (MDD) is hindering identification of potential biomarkers, endophenotypes and aetiological pathways. Reference Antonijevic1,Reference Baumeister and Parker2 This new approach to research on pathophysiological markers has led to the discovery of differences in inflammation and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis activity across subtypes. Reference Penninx, Milaneschi, Lamers and Vogelzangs3 Atypical depression has been linked to higher body mass index (BMI) Reference Lamers, Vogelzangs, Merikangas, de Jonge, Beekman and Penninx4–Reference Cizza, Ronsaville, Kleitz, Eskandari, Mistry and Torvik7 and a higher frequency of metabolic syndrome. Reference Lamers, Vogelzangs, Merikangas, de Jonge, Beekman and Penninx4 People with atypical depression have also been shown to have more inflammation in some studies, Reference Lamers, Vogelzangs, Merikangas, de Jonge, Beekman and Penninx4,Reference Kaestner, Hettich, Peters, Sibrowski, Hetzel and Ponath8–Reference Rothermundt, Arolt, Peters, Gutbrodt, Fenker and Kersting10 but not in others, Reference Anisman, Ravindran, Griffiths and Merali11–Reference Dunjic-Kostic, Ivkovic, Radonjic, Petronijevic, Pantovic and Damjanovic15 whereas melancholic depression was associated with higher cortisol levels. Reference Lamers, Vogelzangs, Merikangas, de Jonge, Beekman and Penninx4,Reference Kaestner, Hettich, Peters, Sibrowski, Hetzel and Ponath8,Reference Karlovic, Serretti, Vrkic, Martinac and Marcinko13,Reference Stetler and Miller16 These results potentially shed a new light on differential aetiologies, but it is not clear yet to what extent this has an impact on the clinical course and whether differences in biological profiles also translate to different somatic health outcome trajectories such as BMI and metabolic syndrome.

So far, cross-sectional and retrospective studies have reported several differences in clinical course between depressive subtypes. However, results are somewhat contradicting with both atypical depression and melancholic depression being associated with chronicity (i.e. chronic course, duration index episode, number of episodes). Reference Lam and Stewart17–Reference Khan, Carrithers, Preskorn, Lear, Wisniewski and Rush22 Only a few prospective studies have evaluated differences in course of depressive subtypes, with one study finding no difference in course between atypical and non-atypical depression, Reference Angst, Gamma, Sellaro, Zhang and Merikangas23 another study finding an initial slower symptom severity recovery but similar severity end-points Reference Sachs-Ericsson, Selby, Corsentino, Collins, Sawyer and Hames24 and one study finding no difference in clinical outcome. Reference Horwath, Johnson, Weissman and Hornig25 One study found the atypical subtype to be a predictor of obesity. Reference Lasserre, Glaus, Vandeleur, Marques-Vidal, Vaucher and Bastardot26 Inconsistencies have also been found for melancholic depression with one study finding melancholic depression to be associated with worse outcomes than non-melancholic depression, Reference Duggan, Lee and Murray27 a study finding more hospital admissions during follow-up but no differences at final follow-up Reference Parker, Hadzi-Pavlovic, Brodaty, Boyce, Mitchell and Wilhelm28 and a study finding no differences in course. Reference Melartin, Leskela, Rytsala, Sokero, Lestela-Mielonen and Isometsa29 Melancholic depression in addition has been associated with increased suicidality. Reference Grunebaum, Galfalvy, Oquendo, Burke and Mann30 Some of the observed discrepancies in the course of depressive subtypes may be because of different methods and definitions used to ascertain subtype. Only one study directly compared atypical and melancholic depression on clinical outcome measures, finding higher remission rates at 16–20 weeks after treatment in people with atypical depression than those with melancholic depression in a naturalistic epidemiological sample of out-patients. Reference Gili, Roca, Armengol, Asensio, Garcia-Campayo and Parker21

Previously, using data from The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) for 818 participants with MDD, we identified different depressive subtypes (severe atypical, severe melancholic, moderate) with the use of data-driven analysis. We have shown that these types have different characteristics and biological profiles. Reference Lamers, Vogelzangs, Merikangas, de Jonge, Beekman and Penninx4,Reference Lamers, de Jonge, Nolen, Smit, Zitman and Beekman31 We also found that the subtypes seemed relatively stable in a group of people with chronic depression over a 2-year period, thus providing further evidence for the validity of the identified subtypes. Reference Lamers, Rhebergen, Merikangas, de Jonge, Beekman and Penninx32 Differences in clinical course would contribute to the clinical relevance of distinguishing these depressive subtypes, but currently, prospective studies on course of subtypes are scarce and are often limited by small sample size or a limited range of outcomes, and lack of direct comparison of different subtypes. The aim of the current 6-year longitudinal study was to compare the course of atypical, melancholic and moderate depressive subtypes. In addition to psychiatric course indicators such as presence of psychiatric diagnoses and suicidality during follow-up, we also evaluated differences in BMI and metabolic syndrome.

Method

Participants

Data are from the NESDA, an ongoing longitudinal naturalistic cohort study of 2981 people, aged 18–65 years at baseline, with lifetime and/or current depressive and/or anxiety disorders (n = 2329, 78%) and healthy controls (n = 652, 22%). Participants were recruited from the community (n = 564, 19%), primary care (n = 1610, 54%) and specialised mental healthcare (n = 807, 27%) from September 2004 to February 2007 at three study sites (Amsterdam, Groningen, Leiden). Exclusion criteria used were: (a) having a primary clinical diagnosis of psychotic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder or severe addiction disorder, and (b) not being fluent in Dutch. A detailed description of the NESDA study design can be found elsewhere. Reference Penninx, Beekman, Smit, Zitman, Nolen and Spinhoven33

For the current study we used the measurements from baseline (T 0) and 2- (T 1), 4- (T 2) and 6-year (T 3) follow-up. At each measurement, a 4 h interview was conducted to collect information on psychopathology, demographics and physical and psychosocial functioning. Also, a medical assessment, computer tasks and self-administered questionnaires were completed. Fasting blood samples were collected, except at the 4-year follow-up. Psychiatric diagnoses were obtained with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) interview, version 2.1, 34 according to DSM-IV criteria. 35 The CIDI interviews were conducted by specially trained clinical research staff.

All people with current (1 month) CIDI-confirmed MDD at baseline whose subtype of depression was previously established (see below) and healthy controls (no baseline lifetime depression and anxiety disorders) who participated in the 2-, 4- or 6-year follow-up were considered for the analysis. There were 743 individuals with subtyped depression and 634 controls (total n = 1377). Of these 1377 eligible people, 129 (9.4%) did not participate in any of the follow-up measurement, leaving a total of 1248 participants to be included in analyses. Individuals lost to follow-up (n = 129) were more often less educated, more often had a diagnosis of MDD and had a higher Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS) Reference Rush, Gullion, Basco, Jarrett and Trivedi36 score (i.e. people from the severe melancholic and severe atypical subtype groups were more prone to loss to follow-up), which is in line with our previous observations regarding attrition in the total NESDA cohort at 2-year follow-up. Reference Lamers, Hoogendoorn, Smit, van, Zitman and Nolen37 Of the 1248 people included in the analysis, 1196 (95.8%) participated in the 2-year follow up, 1121 (89.8%) participated in the 4-year follow-up and 1050 (84.1%) participated in the 6-year follow-up. Within the sample of n = 1248, participation rates at each follow-up assessment were higher in the control group and the moderate subtype group than in the severe melancholic and severe atypical subtype groups (online Table DS1).

Assessment of depressive subtype

To reduce the heterogeneity of depression we applied a data-driven technique – latent class analysis (LCA) – to evaluate clustering of symptoms and to obtain empirically based subtypes of depression, results of which have been previously published. Reference Lamers, de Jonge, Nolen, Smit, Zitman and Beekman31 In short, LCA assumes that an underlying latent categorical variable explains the associations between observed variables (here, depressive symptoms). Reference Hagenaars and McCutcheon38 We used information from the baseline CIDI depression section and a selection of items specific to melancholic or atypical depression from the IDS-self report (IDS30-SR) Reference Rush, Gullion, Basco, Jarrett and Trivedi36 as input for this analysis. The sample included 818 people with current (1 month) MDD (n = 743) or minor depression (n = 75). The best fitting model was a model with three classes (i.e. subtypes). Based on symptom probabilities, the subtypes were labelled as ‘severe melancholic’ (prevalence 46.3%) characterised mainly by decreased appetite and weight loss, but also with the highest probabilities on suicidal thought, psychomotor changes and lack of responsiveness; ‘severe atypical’ (24.6%) characterised mainly by overeating and weight gain, and with the highest probabilities of leaden paralysis and interpersonal sensitivity; and ‘moderate’ (29.1%) that was characterised by lower symptom probabilities and overall lower severity. For the current analyses we only included the 743 people with an MDD diagnosis at baseline. A more detailed description of subtypes and their correlates can be found elsewhere Reference Lamers, de Jonge, Nolen, Smit, Zitman and Beekman31 and in online Supplement DS1.

It should be noted that our labels for subtypes do not refer to the DSM-classifiers. However, robustness of the identified subtypes is shown by other latent modelling studies finding similar symptom patterns Reference Kendler, Eaves, Walters, Neale, Heath and Kessler5,Reference Sullivan, Kessler and Kendler39–Reference Lamers, Burstein, He, Avenevoli, Angst and Merikangas42 and the confirmed stability of subtypes over 2-year follow-up showing 76% of the sample endorsed the same subtype at both measurements. Reference Lamers, Rhebergen, Merikangas, de Jonge, Beekman and Penninx32 Because our labels were used to describe the classes in previous work, we use the same labels here as well for consistency, but readers should remember that our LCA-based subtypes of melancholic and atypical depression differ from the DSM-classification, in the sense that mood reactivity in atypical depression was not a cardinal item and that the number of subtype-specific symptoms does not follow DSM classification.

Outcomes

Outcomes were measured at all follow-up times (unless stated otherwise).

Psychiatric outcomes

Presence of current (1-year) MDD and any anxiety disorder (including generalised anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, panic disorder and social phobia) at 2, 4 and 6 years (T 1–T 3) were assessed using the CIDI. Severity of depression was evaluated with the IDS30-SR. Reference Rush, Gullion, Basco, Jarrett and Trivedi36 As some IDS items were used in defining the subtypes, the use of an IDS score would be inappropriate. We therefore used the Quick IDS (QIDS) Reference Rush, Trivedi, Ibrahim, Carmody, Arnow and Klein43 score with a small adaptation to remove one item used in subgroup definition. Reference Rush, Trivedi, Ibrahim, Carmody, Arnow and Klein43 This adaptation was that instead of calculating the score of the ‘sleep’ domain as the maximum score of four sleep items, we calculated it as the maximum of three items, excluding the item early morning awakening. No other items used in the QIDS calculation overlapped with symptoms used in subgroup definition. Anxiety symptoms were measured with the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Reference Beck, Epstein, Brown and Steer44 manic symptoms with the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ, count of 13 symptoms) Reference Hirschfeld, Williams, Spitzer, Calabrese, Flynn and Keck45 and suicidal ideation in the past week was assessed with the Beck Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire. Reference Beck, Kovacs and Weissman46 Overall functioning was assessed with the 32-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS) Reference Buist-Bouwman, Ormel, De Graaf, Vilagut, Alonso and Van Sonderen47

Somatic outcomes

Weight and height were measured to calculate BMI (weight(kg)/height(m)2). Waist circumference, fasting triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, glucose levels and blood pressure to calculate metabolic syndrome was measured at baseline (T 0) and at 2-year (T 1) and 6-year (T 3) follow-up, and used to define metabolic syndrome according to adjusted Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP-III) criteria. Reference Grundy, Cleeman, Daniels, Donato, Eckel and Franklin48 Besides looking at the presence of metabolic syndrome, we also evaluated a count of metabolic syndrome criteria for a more dimensional measure of metabolic abnormalities.

Statistics

All analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 20. Chi-squared tests for categorical outcome variables, ANOVA for continuous outcome variables and Kruskal–Wallis tests for non-parametric data were used to describe depression subtype groups at baseline. Differences in course trajectory and outcomes between subtypes were assessed by generalised estimating equations (GEE) for dichotomous (binomial model) and count (Poisson model) outcome measures and mixed models for continuous outcome measures using subtype, time and subtype×time as fixed effects. Because the goal of the study was to describe naturalistic course, no other covariates were included. Mixed models were fitted with a random intercept for participant and a repeated time effect, GEE models with a repeated time effect. GEE and mixed models have the advantage that they can take into account within-person correlations and can handle missing observations. All time points were used in the analyses, except for the MDD model from which the baseline measurement was not included as the lack or variance (all participants had MDD at baseline) resulted in a non-convergent model. Several sensitivity analyses were performed, including a model correcting for age and gender, and a model correcting for baseline antidepressant treatment (23.2%). As these results all showed similar patterns and results we only present the main analysis here.

Results

In our initial report on the data-driven depressive subtypes Reference Lamers, de Jonge, Nolen, Smit, Zitman and Beekman31 we showed that the moderate subtype group was of lesser severity, with overall lower comorbidity rates and more favourable values on psychosocial and health outcomes. The current sample – which is a subsample from this study – showed the same pattern of characteristics (Table 1). Severe melancholic and severe atypical depression subtype groups, however, did not differ from each other on clinical characteristics (not tabulated).

Table 1 Baseline description of the depressive subtype and control groups (n = 1248)

| Latent class analysis-based depressive subtype groups | Depressive groups v. controls, P |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe

melancholic (n = 308) |

Severe

atypical (n =167) |

Moderate (n =173) |

Control

group (n = 600) |

Subtypes only P |

||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Female: % | 65.6 | 70.1 | 63.6 | 60.8 | 0.049 | 0.43 |

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 42.3 (11.6) | 40.7 (11.4) | 43.2 (13.0) | 40.8 (14.6) | 0.09 | 0.15 |

| Years education, mean (s.d.) | 11.5 (3.3) | 11.4 (3.3) | 11.6 (2.7) | 12.9 (3.2) | <0.0001 | 0.91 |

| Health indicators | ||||||

| Body mass index, mean (s.d.) | 25.2 (5.0) | 28.3 (5.8) | 25.7 (5.1) | 25.0 (4.6) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Metabolic syndrome, % | 20.2 | 31.1 | 19.3 | 18.7 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Number of metabolic syndrome components, | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| median (IQR) | ||||||

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Age at onset, years: median (IQR) | 25 (16–36.3) | 22 (17–33) | 27 (19–40) | NA | NA | 0.03 |

| Number of episodes, median (IQR) | 1 (1–5) | 1 (1–5) | 2 (1–5) | NA | NA | 0.39 |

| First-degree family history, % | 83.6 | 85.5 | 74.3 | NA | NA | 0.01 |

| Suicidal thoughts, % | 41.9 | 34.3 | 8.1 | NA | NA | <0.0001 |

| Anxiety disorder diagnosis, 1 year: % | 75.3 | 73.1 | 52.0 | NA | NA | <0.0001 |

| Depressive symptomatology (QIDS), mean (s.d.) | 15.1 (4.0) | 15.1 (3.6) | 9.9 (3.7) | NA | NA | <0.0001 |

| Anxious symptomatology (BAI), mean (s.d.) | 22.6 (11.1) | 21.4 (10.9) | 12.5 (7.8) | NA | NA | <0.0001 |

| Manic symptoms (MDQ), median (IQR) | 6.0 (3–9) | 6 (4–8) | 5 (2–7.5) | NA | NA | 0.03 |

| Overall functioning (WHODAS), mean (s.d.) | 41.9 (14.6) | 39.2 (13.8) | 25.4 (12.0) | NA | NA | <0.0001 |

IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; QIDS, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology; BAI, Beck Anxiety Index; MDQ, Mood Disorder Questionnaire; WHODAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule.

Psychiatric diagnoses and clinical characteristics at follow-up within subtypes

Over 6 years of follow-up, all psychiatric outcome measures showed a general improvement. When comparing general course trajectories across the three LCA-based depressive subtype groups, we observed consistent differences between the moderate subtype group compared with the severe subtype groups, but not between the severe atypical and severe melancholic subtype groups.

The moderate subtype group was associated with a more favourable course in all psychiatric outcomes over 6 years compared with the two severe subtype groups. This is visible in the significantly lower prevalence of MDD and anxiety disorders over time, which ranges between 25 and 35% during the follow-up periods as compared with prevalences between 39 and 60% for the severe subtype groups (Fig. 1(a) and 1(b)). The moderate groups also had lower severity scores of suicidal thoughts, depression and anxiety symptoms and disability levels across time (Fig.1(c) and Fig. 2). Significant time×group interactions (online Table DS2) further revealed that the rates of change from baseline for suicidal thoughts, QIDS, BAI and WHODAS were different in the moderate than in the two severe subtype groups, in that relatively more changes over time occurred in the atypical and melancholic depressive subtype groups than in the moderate depressive subtype group.

Fig. 1 Percentage of participants with (a) major depressive disorder (MDD), (b) anxiety disorder and (c) suicidal thoughts over time.

Presented prevalences of MDD, anxiety and bipolar disorder are 1-year diagnoses. Anxiety includes panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia and generalised anxiety disorder. Suicidal thought represents suicidal thoughts in past week. Subtypes are derived from latent class analysis. *P<0.05, **P<0.10; MDD (T 1, T 2, T 3 moderate<melancholic and atypical); anxiety disorder (T 0, T 1, T 2, T 3 moderate<melancholic and atypical; T 1 melancholic>atypical); suicidal thoughts (T 0, T 1, T 2, T 3 moderate>melancholic; T 0, T 1, T 3 moderate<atypical; T 1, T 2 atypical<melancholic). T 0, baseline; T 1, 2-year; T 2, 4-year; T 3, 6-year follow-up.

Fig. 2 Course of (a) depressive symptomatology (Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, QIDS), (b) anxiety symptomatology (Beck Anxiety Index, BAI), (c) World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS) functioning and (d) mania symptoms (Mood Disorder Questionnaire, MDQ) over time.

Subtypes are derived from latent class analysis. *P<0.05, **P<0.10; QIDS (T 0, T 1, T 2, T 3 moderate<melancholic and atypical); BAI (T 0, T 1, T 2, T 3 moderate<melancholic and atypical; T 1, T 2 melancholic>atypical); WHODAS (T 0, T 1, T 2, T 3 moderate<melancholic and atypical; T 0 melancholic>atypical; T 1 melancholic>atypical); MDQ (T 0 moderate<melancholic* and atypical**; T 1 moderate<melancholic and atypical). T 0, baseline; T 1, 2-year; T 2, 4-year; T 3, 6-year follow-up.

The severe melancholic and severe atypical subtype groups were very similar in their 6-year course trajectory on most psychiatric outcomes. The only exceptions were that the severe melancholic subtype group had marginally more anxiety disorder at 2-year follow-up (T 1), marginally more anxious symptoms at 2- and 4-year follow-up (T 1 and T 2), higher WHODAS scores at 2-year follow-up (T 1) and had significantly more suicidal thoughts throughout a large part of the follow-up when compared with the atypical subtype group, although at the 6-year follow-up (T 3) atypical and melancholic subtype groups had similar rates of suicidal thoughts.

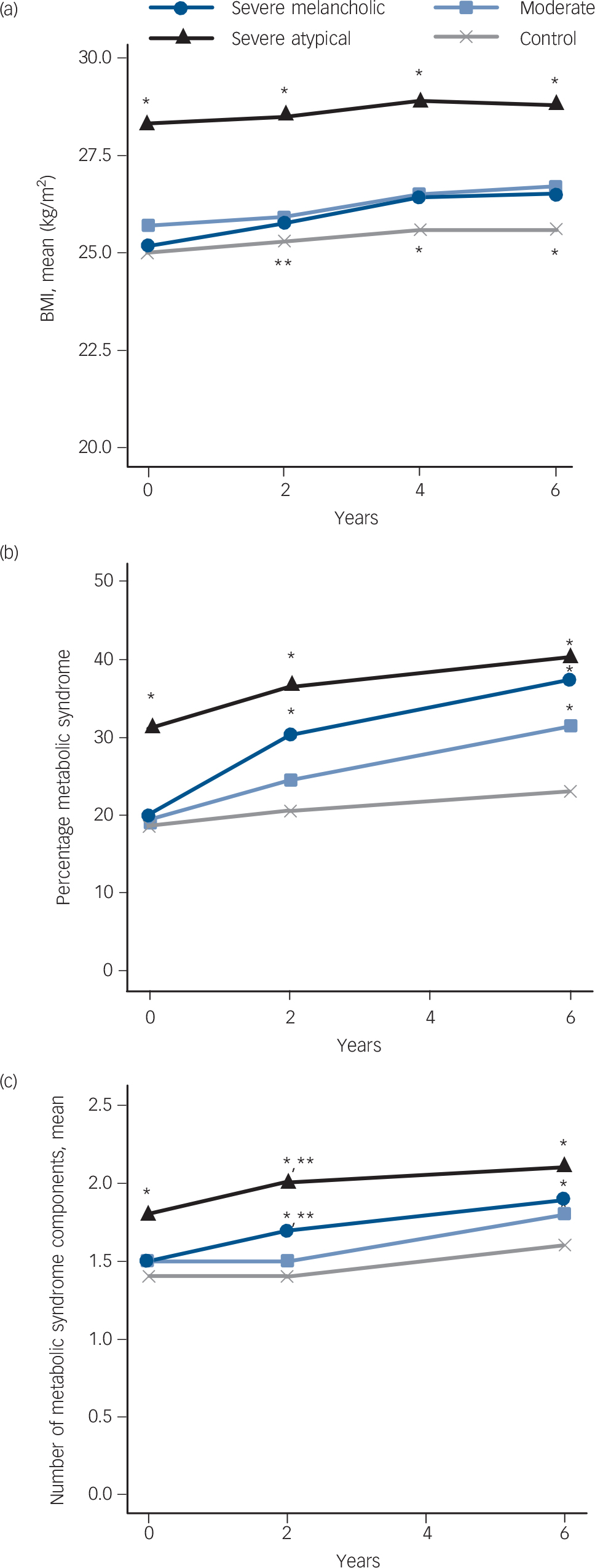

Somatic health characteristics at follow-up with depressive subtype and control groups

Evaluation of BMI and metabolic syndrome showed that the severe atypical subtype group had a poorer course and outcome than the other groups as indicated by significantly higher scores throughout the 6-year follow-up (Fig. 3), although the trajectory of change (i.e. slope of curve) itself was similar to that of the control group, with no significant time×atypical subtype interactions (online Table DS3). The melancholic subtype group showed a steeper rate of increase in BMI, metabolic syndrome and number of metabolic syndrome components than the control group as indicated by significant time×subtype interactions. The atypical depression subtype group also had significantly higher rates of metabolic syndrome and a higher number of metabolic syndrome components at baseline (T 0) and 2-year follow-up (T 1) than the melancholic subtype group; however, at 6-year follow-up (T 3) this difference was no longer significant. Also, the melancholic and moderate subtype groups had a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome and number of metabolic syndrome components than the control group at later follow-up.

Fig. 3 Somatic outcomes over time.

(a) Body mass index (BMI), (b) metabolic syndrome and (c) number of metabolic syndrome criteria. Subtypes are derived from latent class analysis.*P<0.05, **P<0.10; BMI (T 0, T 1, T 2, T 3 atypical>control, melancholic and moderate; T 1 melancholic>control; T 2, T 3 melancholic and moderate>control); metabolic syndrome (T 0 atypical>control, melancholic and moderate; T 1, atypical>control, melancholic and moderate, melancholic>control; T 3 control<atypical, melancholic and moderate); number of metabolic syndrome criteria (T 0 atypical>melancholic, moderate and control; T 1, atypical>moderate* and control*, and melancholic**, melancholic>control* and moderate**; T 3 atypical>moderate and control, control<moderate and melancholic). T 0, baseline; T 1, 2-year; T 2, 4-year; T 3, 6-year follow-up.

Discussion

This study on the course of LCA-based depressive subtypes has two main findings. First, severity was the most important factor predicting course. We found course trajectories to be running parallel to each other for most outcomes and observed that initial differences in severity mostly continued to exist over a 6-year period. Second, the severe atypical and severe melancholic subtype groups did not differ much in course trajectories and outcome on most psychiatric clinical characteristics. However, findings of slightly more anxiety and longer persisting suicidal thoughts throughout follow-up in the severe melancholic than in the severe atypical subtype group indicate that melancholic depression has a somewhat more unfavourable psychiatric clinical course. Also, the atypical subtype group had the least favourable somatic outcomes with continuously high BMI and high rate of metabolic syndrome.

Comparison with findings from other studies

The lack of many differences in course of clinical characteristics in participants with the severe subtypes confirms previous cross-sectional analyses of the subtypes in which no differences were found between severe subtypes, but only between moderate v. severe types. Reference Lamers, de Jonge, Nolen, Smit, Zitman and Beekman31 In contrast to findings in the Zurich cohort study, Reference Angst, Gamma, Sellaro, Zhang and Merikangas23 we did not find that people with atypical depression were more likely to be depressed at follow-up. Parker and colleagues found initial larger decreases in symptom severity scores in individuals with melancholic v. non-melancholic depression, but similar outcomes at 52 weeks, Reference Parker, Hadzi-Pavlovic, Brodaty, Boyce, Mitchell and Wilhelm28 and another study also found only minor course differences between melancholic v. non-melancholic depression. Reference Melartin, Leskela, Rytsala, Sokero, Lestela-Mielonen and Isometsa29 Although our results are therefore in part similar to other studies, a direct comparison is difficult to make because instead of studying people with and without one specific subtype, we compared three subtypes differing both qualitatively (atypical v. melancholic) and quantitatively (severe v. moderate). In the literature, melancholic depression is considered to be the more severe form of depression in comparison with non-melancholic depression. Reference Kendler19,Reference Rush and Weissenburger49 In our study, non-melancholic depression was further divided into severe atypical and moderate subtypes. Although we found marked differences between the moderate and melancholic subtypes, atypical and melancholic subtypes were on the same level for most psychiatric measures. However, the more unfavourable course trajectory of suicidal thoughts – an important clinical indicator of severity – in those with the melancholic subtype nevertheless points to a higher clinical impact of the melancholic subtype.

For somatic outcomes we observed that the group with the atypical subtype continued to have the highest BMI and rate of metabolic syndrome, even after more than half of the group no longer had an MDD diagnosis. We also observed that those with the melancholic subtype seemed to catch up with the atypical subtype group for BMI. The less steep increase in BMI in those with the atypical subtype compared with the melancholic subtype might be explained by relatively more people trying to lose weight in the atypical subtype group, as people with higher initial BMI will be more likely to lose weight. In another study, atypical depression, but not melancholic or unspecified depression, predicted obesity over a 5.5-year follow-up. Reference Lasserre, Glaus, Vandeleur, Marques-Vidal, Vaucher and Bastardot26

Not surprisingly, we also confirmed that severity is a strong prognostic factor, as has been found by others. Reference Keller, Lavori, Mueller, Endicott, Coryell and Hirschfeld50–Reference Conradi, de Jonge and Ormel52 Although some would interpret this as evidence that distinguishing atypical and typical/melancholic depression is perhaps not that relevant, we feel that the pathophysiological differences observed between these subtypes Reference Lamers, Vogelzangs, Merikangas, de Jonge, Beekman and Penninx4,Reference Lamers, de Jonge, Nolen, Smit, Zitman and Beekman31 still warrant further investigation of these subtypes, for instance in studies on genetics and treatment response. An LCA-based atypical subtype – but not a melancholic subtype – was recently found to be associated with an FTO gene variant Reference Milaneschi, Lamers, Mbarek, Hottenga, Boomsma and Penninx53 and with inflammation. Reference Lamers, Vogelzangs, Merikangas, de Jonge, Beekman and Penninx4 Although this FTO finding needs to be replicated, it is an indication that atypical depression and metabolic disturbances have a shared genetic basis. Together with inflammation – which is also associated with high BMI – these metabolic disturbances may be an important target for specific treatment in this group.

Strengths and limitations

The findings of this study should be interpreted in light of some limitations. People who were lost to follow-up tended more often to have more severe depression and one could assume that they have a poorer course. Despite the use of GEE and mixed models – that use all available data instead of complete cases – results may be biased, in that course might be somewhat less favourable in the severe melancholic and atypical subtypes in reality than depicted in this study. Also, the subtypes used are not based on DSM criteria but based on a data-driven classification model, LCA. A systematic review examining the consistency of data-driven subtypes in patients with an MDD diagnosis, also found that depression severity was the most important distinguishing factor rather than specific symptom profiles. Reference van Loo, de Jonge, Romeijn, Kessler and Schoevers54 It should be noted that some LCA studies with more lenient inclusion criteria (for example participants had to have at least one current symptom of depression) showed results similar to our LCA Reference Kendler, Eaves, Walters, Neale, Heath and Kessler5,Reference Sullivan, Kessler and Kendler39,Reference Sullivan, Prescott and Kendler40 and several more studies finding similar subtypes have since been published. Reference Rodgers, Ajdacic-Gross, Muller, Hengartner, Grosse and Angst41,Reference Lamers, Burstein, He, Avenevoli, Angst and Merikangas42 Our data-driven subtypes have further proven their value as they are differentially associated with biological measures (HPA-axis, inflammation, metabolic dysregulation) that imply different aetiological pathways, Reference Lamers, Vogelzangs, Merikangas, de Jonge, Beekman and Penninx4,Reference Lamers, de Jonge, Nolen, Smit, Zitman and Beekman31 which could help to identify underlying pathophysiological mechanisms. Strengths of this study include the relative large groups of different subtypes, the wide range of measures that was assessed and the fact that we had a 6-year follow-up period.

To conclude, course trajectories of LCA-based depressive subtypes mostly ran parallel to each other, with baseline severity being the most important differentiator in course between groups. The more unfavourable somatic health of those with the atypical subtype at baseline continued over time in comparison with the control and the moderate subtype groups, whereas course trajectories of suicidal thoughts and anxiety were most unfavourable in the melancholic subtype group.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.