The worldwide trend in childhood overweight and obesity is now a well-characterised phenomenonReference Wang and Lobstein(1). Where national data are available, adiposity has increased in both pre-school and school-aged children in nearly every country studied. However, large variations in secular trends do appear across countries, and these relate to the degree of economic development and urbanisationReference Wang and Lobstein(1). Increased availability of highly palatable, energy-dense convenience foods and increasing levels of sedentary activity may specifically contribute to rising rates of childhood obesity. Certainly, consumption of fast foods and soft drinks has risen markedly during the same period of timeReference St-Onge, Keller and Heymsfield(2). Given the link between childhood obesity and adult ill-health, how to mitigate these effects has now become an international health imperativeReference Lobstein and Baur(3).

Strong associations between the duration of daily television (TV) viewing and children’s adiposity have been reported in numerous studiesReference Bernard, Lavallee, Gray-Donald and Delisle(4–Reference Reilly, Armstrong, Dorosty, Emmett, Ness, Rogers, Steer and Sherriff10). Moreover, TV viewing behaviour predicts later adiposity, suggesting a causative roleReference Proctor, Moore, Gao, Cupples, Bradlee, Hood and Ellison(9, Reference Jago, Baranowski, Baranowski, Thompson and Greaves11, Reference Viner and Cole12). While this relationship is in part mediated by exerciseReference Jago, Baranowski, Baranowski, Thompson and Greaves(11), much research has also demonstrated that TV viewing is also associated with specific differences in food intake and diet. Increased TV viewing in children and/or adolescents is associated with reduced fruit and vegetable consumptionReference Ortega, Andrés, Requejo, López-Sobaler, Redondo and González-Fernández(13–Reference Matheson, Killen, Wany, Varadt and Robinson16), more snackingReference Francis, Lee and Birch(17, Reference Snoek, Van Strien, Janssens and Engels18), and increased intake of unhealthy and decreased intake of healthy foodsReference Woodward, Cummings, Ball, Williams, Hornsby and Boon(19). Van den Bulck and Van Meirlo found that every additional hour of TV viewed per day equated to an additional 653 kJ consumedReference Van der Bulck and Van Mierlo(20). TV viewing is thus related both to the type and the amount of food consumed.

A link between TV viewing and obesity is clearly a concern, as TV viewing is a popular leisure-time pursuit for children across the globe. In the UK, each week children watch an average of 17 h of programming (both children’s and family), a majority of which is commercial, i.e. broadcasting adverts(21). It has been shown that around half of the advertisements shown during children’s programming in the UK are for food products, of which most are high in fat, sugar and/or saltReference Furnham, Abramsky and Gunter(22–Reference Neville, Thomas and Bauman25), although new regulations regarding such advertising have recently been introduced in the UK(26). A recent US-based study estimated that between 27·2 % and 36·4 % of children’s exposure to non-programme content was for food-related advertsReference Powell, Szczypka and Chaloupka(27). These were for cereals (27·6 %), sweets (17·7 %), snacks (12·2 %), fast-food restaurants (12·0 %) and beverages (8·8 %). Numerous studies have shown that food adverts can alter children’s preference for specific brands as the advertisers would intendReference Brody, Stoneman, Lane and Sanders(28–Reference Gunter, Oates and Blades30). However, more recent data suggest they can also, under certain circumstances, increase energy intakeReference Halford, Gillespie, Brown, Pontin and Dovey(31, Reference Halford, Boyland, Hughes, Oliveira and Dovey32).

A systematic review of the literature on the effects of advertising on consumption in children by Hastings et al.Reference Hastings, Stead, McDermott, Forsyth, MacKintosh and Rayner(33) concluded that food promotion ‘is having an effect, particularly on children’s preferences, purchase behaviour and consumption’. The findings of the Hastings review would suggest that this form of brand promotion has clear effect beyond brand swapping, promoting a diet of energy-dense obesity-promoting foods. Certainly, it seems that children who watch more TV consume more of the most frequently advertised items, as well as less fruit, water and milkReference Vereecken and Maes(34). Generally it is TV viewing and not advert exposure that has been linked to childhood obesity. However, in a recent cross-cultural study which included data from the USA, Australia and eight European countries, a significant association between advert exposure and childhood obesity has been demonstratedReference Lobstein and Dibb(35). Specifically, a clear association between the prevalence of childhood obesity and the number of adverts for sweet and/or fatty foods advertised per 20 h period of child-specific programming was found. It would seem logical then to infer that increased occurrence of obesity is caused by increased exposure to adverts promoting foods high in sugar and/or fat during viewing. However, if this is the case, are obese children more responsive to exposure to food adverts?

Our previous research has shown that recognition of food advertisements correlates with body mass index (BMI)Reference Halford, Gillespie, Brown, Pontin and Dovey(31). However, food advert exposure did not produce any clear weight-status-specific effects on children’s intake or food choice. If food adverts have the same effect on the intake and food choice of all children, irrespective of weight status, can they really be contributing specifically to childhood obesity? In our previous research the sample size was small, and consequently the number of obese and overweight children included in the study was limited. Moreover, in the protocol, an advert recognition task preceded the food intake measurement and therefore this task may have interfered with the effects of our experimental manipulation on food cues. So what is still not certain is whether or not the effects of TV food advertising are more pronounced in obese and overweight children. Consequently, we decided to re-examine the effects of food adverts in a sample of children including a far greater number of obese and overweight individuals in order to determine the effects of weight status on the response.

In our previous study, the ability to correctly recognise food adverts was significantly associated with higher food intake following food advert exposureReference Halford, Gillespie, Brown, Pontin and Dovey(31). It was also found that obese children recognised a greater number, and a greater proportion, of TV food adverts compared with non-food TV adverts. They also recognised more TV food adverts than the normal-weight children. In our previous study we tested advert recognition prior to food intakeReference Halford, Gillespie, Brown, Pontin and Dovey(31). However, this cognitive task may have affected children’s food intake, either by distracting them from the effects of the food adverts or by acting as food stimuli themselves. Therefore, in the present study, food intake measurements were not preceded by the recognition task.

It was hypothesised that: (1) food advert exposure would increase food intake and alter food preferences in children; (2) these effects would be more pronounced in the overweight and obese children; and (3) food advert recognition would be related to children’s weight status.

Methods

Participants

Fifty-nine children (32 male, 27 female) aged between 9 years 6 months and 11 years 2 months (mean 10 years 2 months) were recruited from two classes of a UK school to participate in the study. This was an opportunity sample, no child or parent refused to participate; therefore the children were entirely representative of the two classes. In this study no children dropped out due to illness or for any other reason.

BMI was converted to a standard deviation (sd) score using the revised 1990 reference standardsReference Cole, Freeman and Preece(36). BMI was calculated using the standard formula of weight (kg)/[height (m)]2, and these values were categorised as obese, overweight or normal weight based on published UK age- and gender-related normsReference Reilly, Armstrong, Dorosty, Emmett, Ness, Rogers, Steer and Sherriff(10, Reference Jago, Baranowski, Baranowski, Thompson and Greaves11). Standard deviation from these normsReference Cole, Freeman and Preece(36, Reference Cole, Bellizi, Flegal and Dietz37) for the whole sample was used in analyses to standardise for age- and gender-related differences. This method was used previously in Halford et al.Reference Halford, Boyland, Hughes, Oliveira and Dovey(32). Using these established criteria, 33 (56 %) children were normal-weight (NW), 15 (25 %) were overweight (OW) and 11 (19 %) were obese (OB). This was a higher number and proportion of overweight and obese children than in our previous studiesReference Halford, Gillespie, Brown, Pontin and Dovey(31, Reference Halford, Boyland, Hughes, Oliveira and Dovey32).

Materials

Television advertisements

Three videos were used, containing a collection of 10 non-food related adverts, a collection of 10 food-related adverts, and a cartoon. Advertisements were recorded from children’s and family programming. The products featured in the adverts used in each condition are described in Table 1. Each advert was approximately 30 s in length, for a total advert exposure time in both conditions of 5 min. These adverts were immediately followed by a 10 min cartoon; the same cartoon was used in both conditions.

Table 1 The products represented in both the control condition (toy) adverts and the experimental condition (food) adverts

Foods and food intake measurement

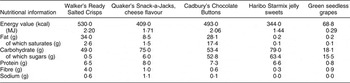

The children were given the opportunity to select and eat from an assortment of foods. The foods offered were: Quaker Snack-a-Jacks (cheese flavour); Haribo jelly sweets; Cadbury’s chocolate buttons; Walker’s potato crisps (ready salted flavour); and fruit (green seedless grapes). Each food item was chosen to represent a specific food category: low-fat savoury, low-fat sweet, high-fat sweet, high-fat savoury and low energy density. The first four food categories were used previously in Halford et al.Reference Halford, Gillespie, Brown, Pontin and Dovey(31) and all five were used in Halford et al.Reference Halford, Boyland, Hughes, Oliveira and Dovey(32). The number of foods offered to each child was limited to five choices due to constraints of space. The nutritional values of the foods used in the study are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Nutritional values of food items used in this study (per 100 g)

Study design

This study utilised a within-subject, counterbalanced design with control (toy advert) and experimental (food advert) conditions. Each child underwent both conditions. For counterbalancing, the order of presentation varied within the sample, so that approximately half of the sample (one school class) took part in the control (toy advert) condition first, the other half of the sample took part in the food advert condition first to minimise order effects. The two sessions were held at the same time on each test day but two weeks apart.

Procedure

Two weeks prior to the study, the children were asked if they wished to take part and consent forms were given to their parents.

On each occasion, the children were told that they would be viewing adverts followed by a cartoon. After viewing, the children were divided into groups of four or five. Each child was then presented with five plates, containing one of each of the five foods in either a standard portion size or 50 g weight, whichever was the greater. The children were instructed that they could eat as little or as much food as they liked, and were asked not to eat from one another’s plates. The children were also told that if they finished the portion of a particular food, more of that food would be provided if they wished. A number of children did request extra food. There was no time constraint; however, neither session lasted beyond 20 min. Once the children had finished eating, the remaining uneaten food was re-weighed. After the second session, weight and height measurements were taken individually, in private, with a member of school staff present at all times.

Analysis

All intake data collected adhered to the assumptions for parametric data, therefore analysis took the form of analysis of variance (ANOVA and MANOVA where appropriate) and t tests. Post hoc comparisons used appropriate repeated-measures or independent-sample t tests. All analyses were completed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences statistical software package, version 14 for personal computer (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Total food intake

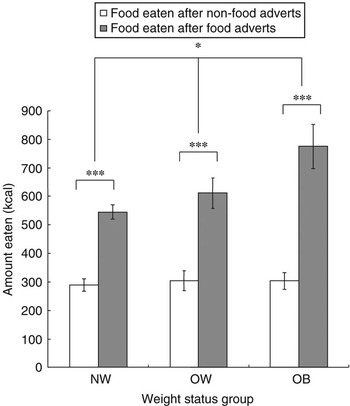

A mixed ANOVA was performed on the total energy consumed by the children between the three weight status categories. Across the group as a whole, total energy intake was significantly higher after exposure to food adverts than after the control (toy) adverts (F(1,56) = 210·751; P < 0·001). There was also a between-participant effect of BMI on total energy intake between the two advert conditions (F(2,56) = 3·398; P = 0·04), with food advert exposure increasing total food intake in the NW (t(36) = 10·454; P < 0·001), OW (t(14) = 11·285; P < 0·001) and OB (t(10) = 5·815; P < 0·001) children by 89 %, 100 % and 155 %, respectively (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Amounts of food eaten by the normal-weight (NW), overweight (OW) and obese (OB) children in the two advertisement conditions. Values are means, with standard error of the mean shown by vertical bars. Mean values were significantly different: *P < 0·05, ***P < 0·001. For conversion of energy values to MJ, multiply kcal by 4·184 and divide by 1000

A significant interaction with BMI status and advert type was also observed (F(2,56) = 7·076; P = 0·002). The significant difference in intake between the three weight status groups was in the food advert condition only (F(2,58) = 6·259; P = 0.004), as all participants consumed a similar amount of food following the control (toy) adverts (F(2,58) = 0·112; P = 0·894). Specifically, following exposure to food adverts, OB children consumed more food than the NW (t(42) = 3·674; P = 0·001) and OW (t(24) = 1·798; P = 0·043) children.

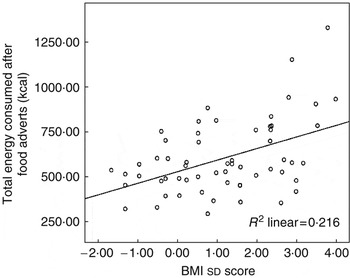

In addition, there was a significant positive correlation between BMI sd score and energy intake after exposure to the food adverts (r(59) = 0·465; P < 0·001) (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Correlation between body mass index (BMI) standard deviation (sd) score and food intake after exposure to the food adverts. BMI converted to sd for age and gender based on published norms. For conversion of energy values to MJ, multiply kcal by 4·184 and divide by 1000

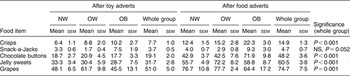

Intake of individual foods

A MANOVA (violation of sphericity) examining the effects of adverts and weight status on food choice was performed. This produced a significant interaction between food choice and advert condition (F(4,53) = 76·140; P < 0·001), whereby food advert exposure increased the intake of all food items (except Snack-a-Jacks) in the group as a whole (see Table 3). With regard to energy intake, in the control (toy advert) condition, children consumed significantly more energy from jelly sweets and chocolate than from crisps, significantly more energy from crisps than from grapes, and significantly more energy from grapes than from Snack-a-Jacks (all tests P < 0·001). While this ranking did not change per se after exposure to the food adverts, the greatest increase in intake was seen in chocolate (152 %), crisps (92 %) and jelly sweets (90 %), and then in grapes (46 %).

Table 3 Mean intake (g) of each food item in both conditions

NW, normal weight; OW, overweight; OB, obese; sem, standard error of the mean.

There was also a significant three-way interaction of food consumption between food type, advert condition and weight status (F(8,108) = 3·429; P = 0·001). Using planned post hoc one-way ANOVAs, it was shown that this significant interaction was due to differences in food intake between the weight status groups. The OB group ate significantly more chocolate buttons and Snack-a-Jacks following the food adverts than both the OW and NW children, and more crisps than the NW children (all tests P < 0·05). The OB group also ate significantly more Snack-a-Jacks in the control (toy advert) condition than both the OW (t(24) = 3·438; P = 0·002) and the NW children (t(42) = 2·867; P = 0·006). There was no statistical difference in the intake of jelly sweets or grapes between weight status groups in either the food advert or control (toy advert) condition.

There were significant positive correlations between BMI sd score and energy intake from chocolate buttons (r(59) = 0·322; P = 0·013), crisps (r(59) = 0·329; P = 0·011) and jelly sweets (r(59) = 0·273, P = 0·037) after exposure to the food adverts. In the control (toy advert) condition, a weak correlation between BMI sd score and crisp intake was observed (r(59) = 0·268; P = 0·04).

Discussion

As predicted, the effect of food advert exposure produced the greatest response in the obese children. The intake response in overweight children was also significantly greater than in the normal-weight children. This is the first clear between-weight-status effect on intake in response to food advert exposure to be demonstrated in our studies. This may have been in part because of the greater proportion and total number of overweight and obese children we were able recruit to this study. Despite a smaller sample and lower proportional obesity, our previous research had found that BMI correlates with food advert recognitionReference Halford, Gillespie, Brown, Pontin and Dovey(31) suggesting that there was an underlying difference in the impact food adverts had on children of differing weight-status, hence the rationale for this study. However, in the previous study, food advert exposure produced equivalent increases in food intake in all children irrespective of their weight status. In fact, in the previous study, trends for weight status differences in overall food intake were apparent in both control (toy advert) and food advert conditions. In contrast, in the present study no weight status differences in total food intake in the control (toy advert) condition were apparent.

Critically, these data provide the first clear definitive picture of an exaggerated intake response to food advert exposure based on weight status. In response to the food adverts, the obese children increased their intake by 1·97 MJ (471 kcal) from the control (toy advert) condition, compared with 1·28 MJ (306 kcal) in the overweight and 1·05 MJ (250 kcal) in the normal-weight children. The increase in intake in the overweight group was primarily driven by an increase in the intake of jelly sweets (0·60 MJ, 143 kcal) and chocolate (0·48 MJ, 114 kcal). Similarly, the increase in intake in the obese children was primarily driven by an increase in chocolate consumption (1·03 MJ, 245 kcal). This suggests that it is the effect of food advert exposure on the intake of sweet, energy-dense foods which differentiates the weight status groups. Moreover, in the food advert condition, total energy intake and intake of all the high-energy-density foods (jelly sweets, chocolate and crisps) were significantly and positively correlated with the children’s standardised BMI scores.

Given that TV viewing is associated with current adiposityReference Bernard, Lavallee, Gray-Donald and Delisle(4–Reference Reilly, Armstrong, Dorosty, Emmett, Ness, Rogers, Steer and Sherriff10) and predicts future weight gainReference Proctor, Moore, Gao, Cupples, Bradlee, Hood and Ellison(9, Reference Jago, Baranowski, Baranowski, Thompson and Greaves11, Reference Viner and Cole12), we believe that obese and overweight children may request more foods merely because of increased advert exposure. Certainly a direct association between TV advertisement exposure and obesity has recently been demonstratedReference Lobstein and Dibb(35). Advert exposure in general has been clearly linked to increased requests for specific itemsReference Buijzen and Valkenburg(38, Reference Pine and Nash39) and this seems to be equally true for food adverts as for toy adverts. Chamberlain et al.Reference Chamberlain, Wang and Robinson(40) demonstrated that total TV viewing and total media exposure are associated with subsequent food and drink requests. Brody et al.Reference Brody, Stoneman, Lane and Sanders(28) showed that advert exposure increased demands for specific advertised food items in subsequent shopping trips. Similarly, Marquies et al.Reference Marquies, Filion and Dafenais(41) also found that time in front of the TV increased requests to parents for advertised foods. In addition, ArnosReference Arnos(42) noted that during TV viewing, over 40 % of children asked their parents to purchase food items they had seen advertised.

Given the nature of the foods promoted on TV, if these requests translated into purchases and consumption this could only have a negative impact on dietReference Furnham, Abramsky and Gunter(22–Reference Neville, Thomas and Bauman25, Reference Powell, Szczypka and Chaloupka27, Reference Brody, Stoneman, Lane and Sanders28). However, research is needed to determine if the mere degree of exposure and not individual differences in responsiveness predict these weight status differences. The notion that the obese may be more responsive to external food cues is also well established in the literatureReference Schacter(43). Perhaps the relationship between food promotion and obesity is in part independent of total TV viewing time or total advert exposure?

With regard to the experimental manipulation, these results clearly replicate our previous findings that exposure to food advertisements increases food intake in childrenReference Halford, Gillespie, Brown, Pontin and Dovey(31). Advert exposure produced varying changes in intake of all of the differing food items offered to the children. The effect was greatest for the three most energy-dense foods (high in fat and/or sugar). The intake of the low-fat savoury food item was very low. Halford et al.Reference Halford, Gillespie, Brown, Pontin and Dovey(31) also showed that in both the control (toy advert) condition and the food advert condition, the least consumed snack was the low-fat savoury option. There are probably two interrelated factors mediating the effects of TV viewing on energy intake: first, the type of foods that are easiest to consume while viewing; and second, the type of foods most promoted during viewing (both during family programming and in many countries still promoted during children’s programming also)Reference Furnham, Abramsky and Gunter(22–Reference Neville, Thomas and Bauman25, Reference Powell, Szczypka and Chaloupka27, Reference Brody, Stoneman, Lane and Sanders28). These items are often snack foods high in fat and sugar, and are likely to promote positive energy balance.

In this study, the low-fat savoury item was again the least preferred, as commented on beforeReference Halford, Boyland, Hughes, Oliveira and Dovey(32). Low-fat savoury snack items probably do not feature significantly in children’s habitual diets and consequently it is hard to find one that children will consume a substantial amount of when presented alongside more familiar and favoured itemsReference Halford, Gillespie, Brown, Pontin and Dovey(31, Reference Halford, Boyland, Hughes, Oliveira and Dovey32). There are obvious limitations to the use of only four or five food items to assess children’s habitual taste preferences and the effect of advert exposure on them. However, the number of food items which realistically can be offered to each child is limited. Questionnaire-based tools are more appropriate if a more comprehensive assessment of the effect of food advert exposure on food preference and food choice is required.

What is particularly distinct in these data is that the total increase in energy intake and the increases in the intake of each of the foods were far greater in magnitude than previously reported, with the total energy intake doubling after exposure to food adverts. In this respect, the results contrast markedly with our previous findings. In the present study, the stimuli and the foods offered were very similar to those offered beforeReference Halford, Gillespie, Brown, Pontin and Dovey(31); therefore it is most likely that the change in procedure altered the response. The removal of the advert recognition test reduced the time from advert exposure to the experimental eating opportunity from over 15 min (cartoon viewing and 5 min to complete the recognition task) to just 10 min (cartoon viewing only), strengthening the salience of the cue. However, this change in magnitude of the effect was probably also due to the fact that only one rather than two events occurred between the stimuli exposure and the food eating opportunity. While the effect of a specific exposure can initially be quite dramatic, the effects dissipate fairly quickly especially if attention is diverted to a cognitive task such as recognition. Whether increased duration between adverts and eating opportunity, or distraction is the more potent effect at dissipating the effects of food adverts on subsequent intake remains to be tested.

This was an experimental study in a relatively small but (in terms of distribution of body weight) a fairly representative sample of UK children in this age group. Rather than using an opportunity sample, another approach would have been to recruit children in each of the three weight status categories to produce three weight status groups with equal numbers; however, matching these groups for age, gender and socio-economic background may be difficult. Caution must be taken when generalising the results of small-scale experimental studies to real-world behaviour. However, these data provide clear evidence of weight status differences, both in terms of total energy intake and in food choice, in response to food advert exposure, differences that were not apparent from our previous work. Moreover, they again demonstrate the statistically significant effect of advert exposure on children’s food choice and total energy intake. These factors may well be critical in explaining the link between TV viewing, advert exposure and childhood obesity.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded wholly by the University of Liverpool. The original study was designed by J.C.G.H. and T.M.D.; the experimental procedures were piloted, the data were collected and a preliminary analysis was performed by S.M. and L.S.; G.M.H. and E.J.B. also helped in the development of the study protocol, the preparation of study materials and purchasing of study foods, generated additional data and analysed the full data set. All six authors contributed to the first draft of the manuscript. J.C.G.H. and E.J.B. handled submission and revision. J.C.G.H. has recently received research support from Lipid Nutrition and has also recently worked with Danone UK and GlaxoSmithKline, all on unrelated projects. E.J.B.’s postgraduate study is supported by the School of Psychology, University of Liverpool. The authors wish to acknowledge our colleagues in the Human Ingestive Behaviour Laboratory, in particular Dr Joanne Harrold and Professor Tim Kirkham, for their time and support.