Dementia is a clinical syndrome characterised by a decline from a previously attained cognitive level affecting a person’s activities of daily living and social functioning. Alzheimer’s disease is the commonest cause of dementia, followed by vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, and frontotemporal dementia. Globally there were ~47 million people living with dementia in 2015, a number expected to rise to 131 million by 2050 (Prince et al. Reference Prince, Wimo, Guerchet, Ali, Wu and Prina2015) primarily driven by increased longevity. The World Health Organisation’s (2017) Global Action Plan identifies dementia as a global priority urging key stakeholders to put in place necessary policies and resources that would ensure priority ‘to action in dementia’. The Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care provides an evidence-driven report that can act as a vehicle for implementing specific interventions for the prevention and management of dementia (Livingston et al. Reference Livingston, Sommerlad, Orgeta, Costafreda, Huntley, Ames, Ballard, Banerjee, Burns, Cohen-Mansfield, Cooper, Fox, Gitlin, Howard, Kales, Larson, Ritchie, Rockwood, Sampson, Samus, Schneider, Selbaek, Teri and Mukadam2017).

The aim of the report was to consolidate the evidence base through the involvement of experts from a variety of disciplines and countries and add to it. The specific recommendations are about transforming the lives of people with dementia and their families through prevention, intervention, and care. The full report can be accessed here: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)31363-6/fulltext. For this editorial we summarise the key recommendations of the Commission into two main categories; those related to prevention, and those related to intervention and care.

Prevention of dementia recommendations

The number of people with dementia is increasing globally, especially in low- and middle-income countries (Prince et al. Reference Prince, Wimo, Guerchet, Ali, Wu and Prina2015). Recent studies suggest that changes have been occurring, with decreases in the age-specific incidence or prevalence in the United States, United Kingdom, Sweden, the Netherlands, France, and Canada, probably reflecting reduced exposure to risk factors or increased resilience to cognitive decline, but in others, for example, Japan and China this is not the case (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Wang, Wu, Liu, Theodoratou, Car, Middleton, Russ, Deary, Campbell, Wang and Rudan2013; Okamura et al. Reference Okamura, Ishii, Ishii and Eboshida2013). Identifying and modifying risk could translate to a huge benefit for societies, individuals, and health care systems. Prevention is always preferable to cure but this is particularly important in view of the absence of disease modifying treatments of the underlying illness. Any delay in the onset of dementia will be associated with significant health gains for individuals and society.

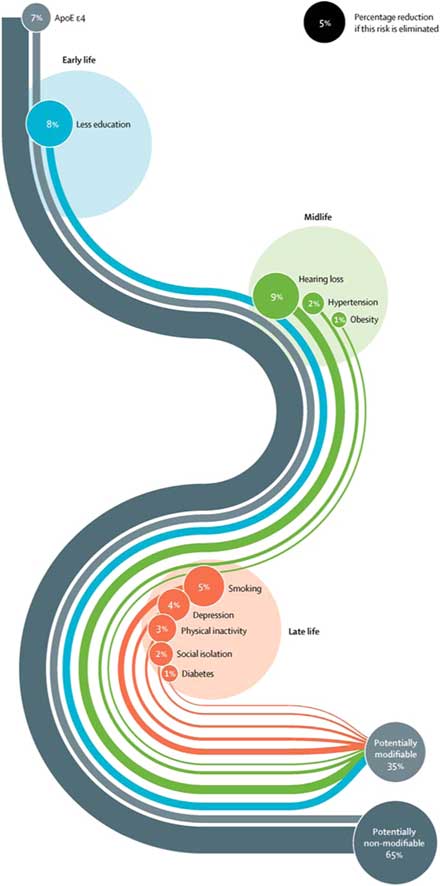

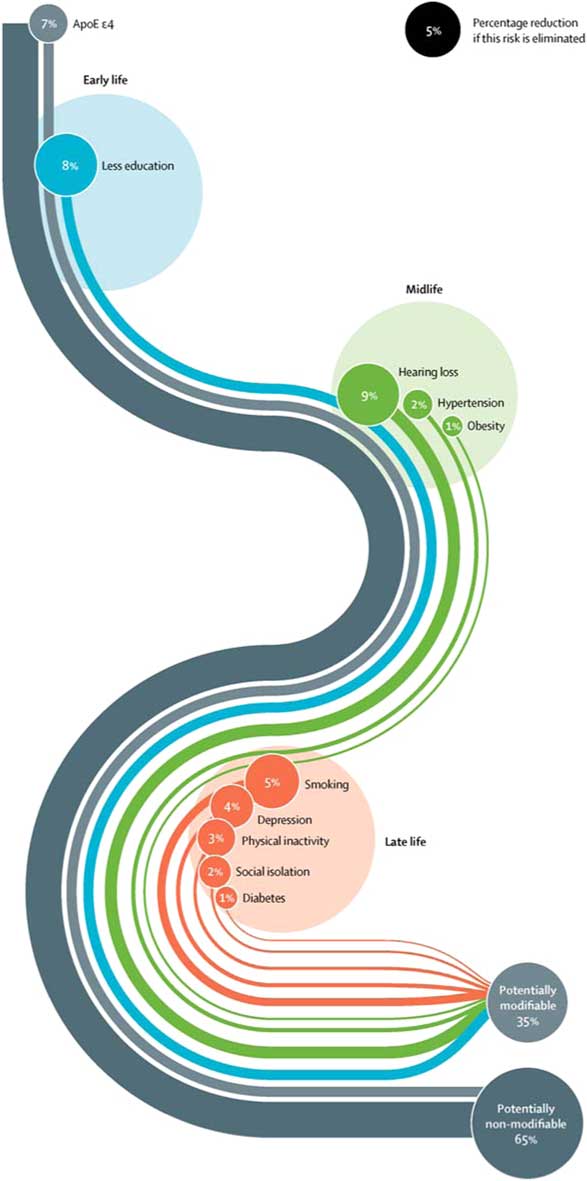

The Lancet Commission extends our knowledge of dementia prevention by calculating and presenting a new model approach to modifiable risk factors (Livingston et al. Reference Livingston, Sommerlad, Orgeta, Costafreda, Huntley, Ames, Ballard, Banerjee, Burns, Cohen-Mansfield, Cooper, Fox, Gitlin, Howard, Kales, Larson, Ritchie, Rockwood, Sampson, Samus, Schneider, Selbaek, Teri and Mukadam2017). This model estimates the population attributable fraction, which is the proportional (percentage) reduction in new cases of dementia that would occur if specific risk factors were completely eliminated. The risk factors included in this model are those identified by the UK National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (2015) and the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Daviglus et al. Reference Daviglus, Bell and Berrettini2010) guidelines, with those qualifying on ‘best-quality evidence’ being added. What is new and important about this model is that it takes a life-course approach to dementia prevention, considering that risk factors and their contribution to risk of dementia differ across the life span, and additionally calculates the contribution of emerging risk factors that have not been considered before – hearing loss and social isolation. These nine risk factors were education (the effect of which is mostly in early life), hearing loss, hypertension, and obesity (mid-life) and late life factors specifically smoking, depression, physical inactivity, social isolation, and diabetes (see Table 1).

Table 1 Potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia

This new model found that more than a third of dementia cases are potentially preventable with collectively all nine factors accounting for 35% of the population dementia risk. Although it is impossible to completely eliminate these risks, the evidence of incidence reductions to date of around 20% strongly suggests that preventive strategies have the potential to delay or prevent dementia. Fig. 1 shows the Lancet Commission life-course model of the nine key modifiable risk factors to dementia, delineating each factor’s contribution.

Fig. 1 Life-course model of contribution of modifiable risk factors to dementia.

We were surprised to find that hearing loss was the largest contributor. This was accounted for by the strength of the association with dementia, almost doubling the risk, and by how common hearing loss is. Overall, we found that the most promising intervention targets were increasing education in early life, increasing physical activity and social engagement, reducing smoking, treating hypertension, diabetes, and hearing impairment. These are unlikely to be harmful and would also benefit people in other ways.

Recommendations for intervention and care for people with dementia and their families

Diagnosis is a prerequisite for accessing interventions, and therefore we view timely diagnosis as the vehicle to accessing timely care (for further information on early diagnosis see the full Lancet Commission report; Livingston et al. Reference Livingston, Sommerlad, Orgeta, Costafreda, Huntley, Ames, Ballard, Banerjee, Burns, Cohen-Mansfield, Cooper, Fox, Gitlin, Howard, Kales, Larson, Ritchie, Rockwood, Sampson, Samus, Schneider, Selbaek, Teri and Mukadam2017). The Commission emphasises that although the underlying illness is not curable, many of the symptoms of dementia are now manageable, therefore the course of dementia and its symptoms changes with good dementia care. In the section below we review interventions that are effective and improve outcomes for people with dementia and their families, and should therefore be implemented now.

The report highlights that good dementia care is individualised, which means that people with dementia and their families need to have their medical, social, and supportive care needs assessed and re-assessed over time as they change. They should be tailored to individual’s cultural needs, preferences, and priorities. Cholinesterase inhibitors are in routine use for treating cognitive symptoms, and although they do not change the neuropathology of the disease, they have a small but clinically important effect on cognition and function at all Alzheimer’s disease severities (Birks, Reference Birks2006), and are also effective in dementia with Lewy bodies (McKeith et al. Reference McKeith, Del Ser, Spano, Emre, Wesnes, Anand, Cicin-Sain, Ferrara and Spiegel2000). Optimal doses also benefit global change and activities of daily living (Birks, Reference Birks2006).

Family carers of people with dementia are at increased risk of experiencing depression, with ~40% being at increased risk of developing clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety (Mahoney et al. Reference Mahoney, Regan, Katona and Livingston2005). Treating carers’ psychological distress and specifically depression is important for the individual and in addition, the presence of carer distress predicts care breakdown, admission to home care (Gallagher et al. Reference Gallagher, Ni Mhaolain, Crosby, Ryan, Lacey, Coen, Walsh, Coakley, Walsh, Cunningham and Lawlor2011), and increases risk of elder abuse (Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Selwood, Blanchard, Walker, Blizard and Livingston2010). There are effective interventions such as the STrAtegies for RelaTives (START) (Livingston et al. Reference Livingston, Barber, Rapaport, Knapp, Griffin, King, Livingston, Mummery, Walker, Hoe, Sampson and Cooper2013) or the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health intervention (REACH) (Gitlin et al. Reference Gitlin, Belle, Burgio, Czaja, Mahoney, Gallagher-Thompson, Burns, Hauck, Zhang, Schulz and Ory2003), which reduce risk of depression for carers and should therefore be made available. People with dementia and their families also need opportunities to discuss their views on plans about the future, considering the loss of capacity associated with more severe dementia. Health care professionals should discuss these views at an early stage to maximise the involvement of people with dementia.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia are common, affecting nearly every individual at some point in the illness. They increase severity of dementia symptoms and distress experienced by family carers and often mean that care at home breaks down (Savva et al. Reference Savva, Zaccai, Matthews, Davidson, McKeith and Brayne2009). These symptoms can have many causes and often several cluster together therefore their careful assessment is important (Lyketsos et al. Reference Lyketsos, Sheppard, Steinberg, Tschanz, Norton, Steffens and Breitner2001). The Commission published algorithms incorporating strategies for managing neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia particularly agitation, low mood, and psychosis which is usually psychological, social, and environmental, with pharmacological management restricted to people who experience severe symptoms. An important contribution of the Commission is the provision of guidance for clinicians and professionals involved in the care of people with dementia, describing the key principles and approaches to assessment and management of each of these symptoms (Livingston et al. Reference Livingston, Sommerlad, Orgeta, Costafreda, Huntley, Ames, Ballard, Banerjee, Burns, Cohen-Mansfield, Cooper, Fox, Gitlin, Howard, Kales, Larson, Ritchie, Rockwood, Sampson, Samus, Schneider, Selbaek, Teri and Mukadam2017).

The report highlighted that people with dementia are vulnerable to risks including self-neglect, vulnerability (including to exploitation), managing money, driving, or using weapons (Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Selwood and Livingston2008; Cooper & Livingston, Reference Cooper and Livingston2014). Risk assessment and management at all stages is essential, balancing severity of risk against the person’s right to autonomy. Given that dementia shortens life span, and a third of older people die with dementia, the Commission recommends that professionals working in end-of-life care consider whether a patient has dementia, as they might be unable to make decisions, or express their needs and wishes. Technological interventions have the potential to improve care, assisting people with dementia to live in safe and stimulating environments, but caution is needed so that these interventions are for specific benefit rather than to replace social contact.

Conclusions

This editorial has reviewed the key messages of the Lancet Commission on Dementia, placing an emphasis on what we can do now to prevent and intervene for dementia. In summary, the Commission’s key findings show that a large proportion of dementia is preventable and ‘acting now’ will have a huge benefit for societies and individuals worldwide. An important life-course approach, accommodating exposure to specific risk factors across the life span is presented, and urges us to think that ‘it is never too early and never too late’ to prevent dementia. The report also addresses the significant developments in interventions that improve outcomes for people with dementia and their families which should be routinely offered. This means we have made significant progress and are much closer to safe, widely accessible, high-quality dementia care.

Acknowledgements

For the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care report, we were partnered with University College London, and received financial support from the Alzheimer’s Society (AS), UK, the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), and Alzheimer’s Research UK (ARUK). The Lancet commission received financial support from the AS, ESRC and ARUK. Vasiliki Orgeta is funded by the Alzheimer’s Society. N.K. is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (DRF-2012-05-141). A.S. is funded by the Welcome Trust. All authors are supported by the UCLH NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. G.L. was (in part) supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) North Thames at Bart’s Health NHS Trust. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Financial Support

This article received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The author asserts that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.