Introduction

The Coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) was first discovered in China at the end of 2019 and rapidly spread across the world in 2020. At the end of 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic had killed more than 5 million people worldwide and more than 290 million positive cases had been identified.

Early legitimate concerns that the COVID-19 pandemic may lead to an increased number of self-harming behaviors [Reference Gunnell, Appleby, Arensman, Hawton, John and Kapur1] were not realized. Indeed, initial reports showed reduced or stable rates of both suicide deaths and non-lethal self-harms during the early months of the pandemic [Reference Hawton, Casey, Bale, Brand, Ness and Waters2, Reference Pirkis, John, Shin, DelPozo-Banos, Arya and Analuisa-Aguilar3]. In France, an 8.5% reduction in the total number of hospitalizations for self-harm was found between March and August 2020, a decrease starting abruptly the first week of the first lockdown and persisting until the end of August when positive cases and deaths due to COVID-19 were low [Reference Jollant, Roussot, Corruble, Chauvet-Gelinier, Falissard and Mikaeloff4]. The decrease was observed in both men and women and in all age groups except older people.

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants then caused a second wave from September to November 2020, a third wave in February–May 2021 (alpha variant), and a fourth wave in July–August 2021 (delta variant). Social distancing measures, travel restrictions, and lockdowns/curfews were reimplemented. Despite the promising start of the vaccination campaign in December 2020, national surveys showed high levels of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and suicidal ideas in the general population in France [5] and some studies additionally suggested that postlockdown periods may be marked by more severe clinical conditions [Reference Ambrosetti, Macheret, Folliet, Wullschleger, Amerio and Aguglia6], raising the possibility of a delayed impact on self-harm rates. Clinicians particularly alerted in media of the situation in young people and an early study reported an increasing number of visits at an emergency room in Paris in people aged 15-year-old and below starting in September 2020 [Reference Cousien, Acquaviva, Kernéis, Yazdanpanah and Delorme7].

The present study primarily aimed to investigate the prolonged impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospitalized self-harm patients by comparing the period between September 2020 to August 2021 (covering the second, third, and fourth infectious waves) with 2019 as the reference pre-COVID year. To this aim, we used a large and exhaustive national hospital database. A secondary objective was to identify similarities and differences in trends in self-harm hospitalizations between this period and the first months of the pandemic (March–August 2020) [Reference Jollant, Roussot, Corruble, Chauvet-Gelinier, Falissard and Mikaeloff4]. This latter objective will be presented in section “Discussion.” We hypothesized that findings from this second period would differ from the first months, notably in relation to an increasing number of self-harms in adolescents, suggesting two different stages of the pandemic in terms of effects on self-harm.

Methods

The methods used here have been previously described in detail [Reference Jollant, Roussot, Corruble, Chauvet-Gelinier, Falissard and Mikaeloff4]. We used the same design as in the previous study covering the March–August 2020 period.

Design

This is a retrospective observational study.

This manuscript follows the RECORD reporting guidelines for observational studies using routinely collected health data.

Population

All patients aged 10 years or older, who were hospitalized for self-harm in medicine/surgery/obstetrics in France (including overseas territories) between January 1, 2019 and August 31, 2021 were included. However, the current analyses only focused on the comparison between the January–December 2019 period as the last pre-COVID comparison period, and the September 2020–August 2021 period as the studied period.

Database

All data were extracted from the national Programme de Médicalisation des Systèmes d’Information (PMSI) database, an exhaustive collection of discharge summaries for all patients hospitalized in public and private hospitals in France. The authors had full access to the data.

Variables

The main outcome was the total number of hospitalizations for self-harm in France during the period September 1, 2020 to August 31, 2021 as compared to the period January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019 (pre-COVID period). We chose this period as the reference period (instead of September 2018–August 2019) for two reasons: (a) there are historical downwards trends in self-harm hospitalization in France so the reference period should be as close as possible to the studied period; and (b) 2019 was the reference period for our previous investigation of the March–August 2020 period [Reference Jollant, Roussot, Corruble, Chauvet-Gelinier, Falissard and Mikaeloff4], allowing a certain level of comparison in findings between the two COVID periods.

The outcome was analyzed by month and week, and according to 10-year age bracket and sex.

Self-harm was identified by an ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision) code X60 to X84 registered as an associated diagnosis.

The secondary outcomes were the changes in the self-harming means, total number of hospital stays per patient, mean duration of hospital stays (in days) per patient, number of hospital stays in an intensive care unit, and hospital mortality following hospitalization for self-harm.

Statistical analyses

Differences in the number of hospitalizations (per month, year, age group, sex, self-harming act) between the pre- and post-COVID periods were estimated by Relative Risks (RR) and presented with 95% Confidence Intervals [CI] using a modified Poisson regression model, as described by Zou [Reference Zou8] who suggested using a modified Poisson approach to estimate the relative risk and confidence intervals by using robust error variances. In our study, the robust error variances can be estimated using the SAS GENMOD procedure with the “repeated” statement. In our analyses, the subject identifier was the unique ID number of each hospital stay considered. A two-sample Student’s t-test was used to compare the mean number of stays and the mean length of stay per patient during the two periods. A Cox proportional-hazards regression model was applied to evaluate hospital mortality during the two periods, taking into account the length of stay for patients who died at the hospital.

The p-value was set a priori at 0.05 for all analyses.

All analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Version 9.4, Cary, NC).

Results

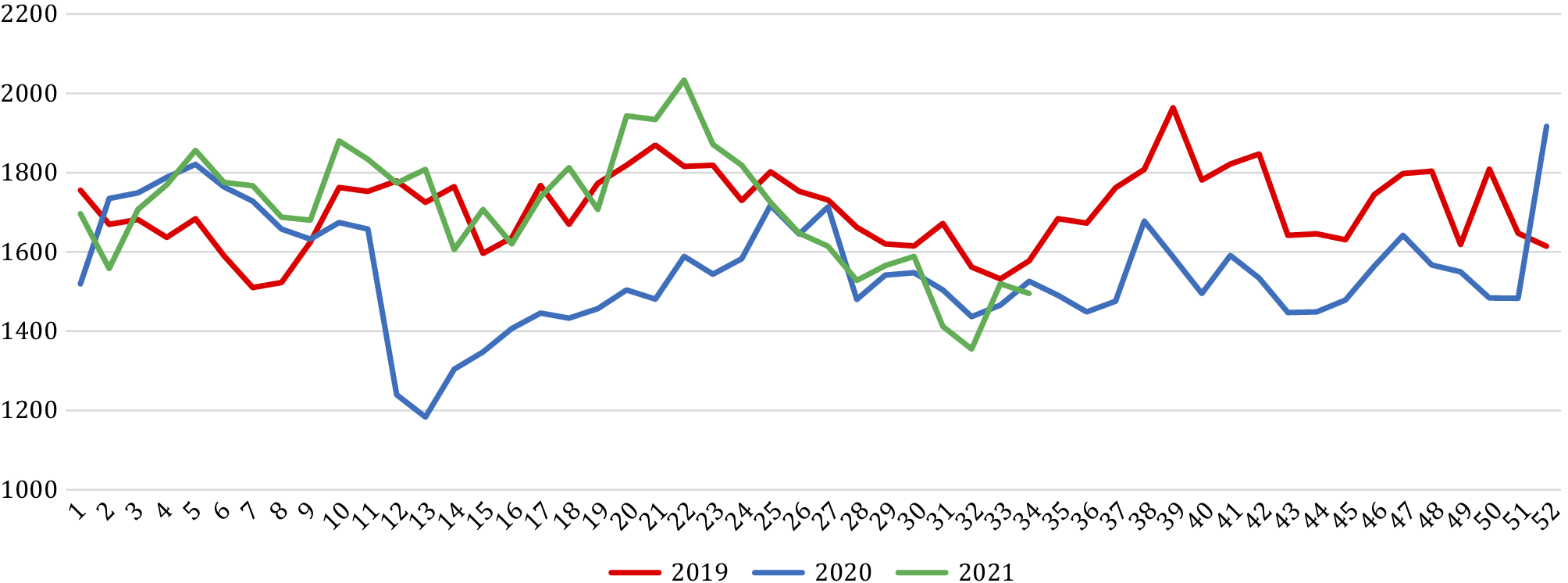

There were a total of 228,727 hospitalizations for self-harm between January 1, 2019 and August 31, 2021, representing 180,471 patients. Weekly and monthly numbers are shown in Figures 1 and 2. As expected, this population comprised more women than men (61.3% vs. 38.7%) and the main self-harming means used were drug overdoses (72.4%) and use of sharp objects (10.7%).

Figure 1. Number of monthly hospitalizations for self-harm in France in 2019, 2020, and 2021 (until August only) and representation of national confinements, curfews, and infectious waves. Red lines: infectious waves (February–August 2020 possibly starting end of 2019; September–December 2020; January–June 2021; July–August 2021). Brown squares: national confinements (March 17–May 11, 2020; October 30–December 15, 2020; March 31–May 3, 2021). Yellow squares: national curfews (October 14–October 30, 2020; December 15, 2020–March 31, 2021; May 3–June 20, 2021). Pink: Reference period (2019), Blue: first stage of the pandemic (*data available in Jollant et al. [Reference Jollant, Hawton, Vaiva, Chan-Chee, du Roscoat and Leon32]); Green: Studied period (September 2020–August 2021).

Figure 2. Number of weekly hospitalizations for self-harm in France in 2019, 2020, and 2021 (until August only). The number of hospitalizations at week 53 in 2020 was added to week 52 as there was official no week 53 in 2019 leading to an artificially increased number for this week.

Comparison of the September 2020–August 2021 period and 2019

Overall, there were fewer self-harm hospitalizations during the September 2020–August 2021 period as compared to January–December 2019: 85,679 versus 88,782 (−3,103 representing −3.5%; RR [95% CI] = 0.97 [0.96–0.97]; p < 0.0001). However, the monthly changes differed over the studied period (Table 1), with a persisting decrease ranging from −10.0 to −14.9% between September and December 2020, followed by a more fluctuating pattern between January and June 2021, then a decrease in July and August 2021.

Table 1. Number of monthly hospitalizations for self-harm in France in September 2020–August 2021 compared to January–December 2019.

Note: Relative risk from Poisson regression model. For January–August 2020 versus 2019 numbers and statistics, please see Jollant et al. [Reference Jollant, Hawton, Vaiva, Chan-Chee, du Roscoat and Leon32]. Lancet Regional Health Europe 2021.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

* p < 0.05;

** p ≤ 0.001;

*** p ≤ 0.0001.

Differences were observed by sex, with a significant decrease found during the studied period versus 2019 for men (−8.0%; RR = 0.92 [0.91–0.93]; p < 0.0001) but not women (−0.6%; RR = 0.99 [0.98–1.01]; p = 0.3) (Table 2). Men represented 88.9% of the global decrease in numbers during this period.

Table 2. Number of hospitalizations for self-harm in France in September 2020–August 2021 compared to January–December 2019, per age group and sex.

Note: Relative risk from Poisson regression model.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

* p < 0.05;

** p ≤ 0.001;

*** p ≤ 0.0001.

A significant effect of age was also found (Table 2 and Figure 3). There was a large increase in self-harm hospitalizations in women aged 10–19 years (+27.7%, RR = 1.28 [1.25–1.31]; p < 0.0001); and a stability in numbers in male adolescents aged 10–19, in both sexes among 20–29-year-olds, and in people above 70. All other age groups showed decreasing trends during the studied period versus 2019. Large decreases were notably found for middle-aged adults (30–59-years-old) in both men and women.

Figure 3. Changes (in %) in the number of hospitalizations for self-harm in France in September 2020–August 2021 compared to January–December 2019, per age group and by sex.

When focusing on 10–19-year-old female adolescents, the annual trends in self-harm hospitalizations (Figure 4) showed the expected seasonal pattern (lowest in summer, highest in winter and spring), but a more marked increase during winter and spring 2021 versus 2019. It was followed by a decrease during summer 2021, although the number of hospitalizations during the 2021 summer period remained higher than in summer 2019 and summer 2020.

Figure 4. Number of monthly hospitalizations for self-harm in France in 2019, 2020, and 2021 (until August only) per age group in women (top) and men (bottom).

All types of self-harm means significantly decreased or were stable as compared to 2019, except for use of sharp objects and jumping from height (Table 3). In female adolescents aged 10–19, significant increases were found for use of sharp objects (+48.9%; RR = 1.49 [1.43–1.56]; p < 0.0001), drug overdose (+18.4%; 1.18 [1.15–1.22]; p < 0.0001), alcohol use (+26.5%; 1.27 [1.04–1.53]; p < 0.05), use of chemicals (+19.2%; 1.19 [1.01–1.40]; p < 0.05), hanging and strangulation (+48.7%; 1.49 [1.26–1.76]; p < 0.0001), jumping from height (+28.8%; 1.29 [1.05–1.57], p < 0.05), and use of other/unspecified means (+45.2%; 1.45 [1.30–1.63]; p < 0.0001).

Table 3. Number of hospitalizations for self-harm in France in September 2020–August 2021 compared to January–December 2019, according to the self-harm means and characteristics of hospital stays.

Note: Relative risk from Poisson regression model; £, Student t-test; §, Cox model.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

* p < 0.05;

** p ≤ 0.001;

*** p ≤ 0.0001.

The number of hospitals stays per patient and the hospitalization duration slightly increased during the studied period versus 2019.

Finally, a significant global decrease in self-harm hospitalization in intensive care units was found compared to 2019, while no change in the number of deaths in hospital following self-harm was observed (Table 3). In adolescent girls, however, the number of intensive care unit hospitalizations increased during the studied period versus 2019 (+20.6%; RR = 1.21 [1.05–1.39]; p < 0.05).

Discussion

General findings and comparison with the first months of the pandemic

As compared to 2019 (the last pre-COVID year), the COVID-19 pandemic during the period September 2020–August 2021—covering the second, third, and fourth infectious waves—showed different patterns in self-harm hospitalizations compared to the early months of the pandemic and the first infectious wave (March–August 2020) [Reference Jollant, Roussot, Corruble, Chauvet-Gelinier, Falissard and Mikaeloff4] (see summary Table 4). First, the global decreasing trends observed during the first stage of the pandemic persisted but at a lower intensity. This was particularly the case for 30–59-year-old adults until the end of the studied period in August 2021. Second, young people (10–29-years-old) showed a very different temporal pattern, suggesting a delayed effect. The decrease in self-harm hospitalizations observed in these age groups during the first pandemic stage was replaced by (a) a large increase in hospitalized self-harms in teenage girls (notably between January and June 2021) and the use of more violent acts in this population, and (b) similar levels of self-harming behaviors as compared to 2019 in 10–19-year-old boys and in 20–29-year-olds in both sexes. Third, people above 70-years-old continued to show similar levels of hospitalized self-harm as in 2019, with no decrease since the start of the pandemic. Finally, hospitalization in intensive care units decreased (with the notable exception of teenage girls) and deaths at hospital were comparable to 2019, suggesting no global negative impact of the pandemic on more lethal acts to date.

Table 4. Summary of findings by age group and gender during the first (March–August 2020, Jollant et al. [Reference Jollant, Hawton, Vaiva, Chan-Chee, du Roscoat and Leon32]) and second (September 2020–August 2021) stages versus 2019.

A global decrease in self-harm hospitalizations

Concerns that the prolongation of the pandemic may be associated with significant increases in the number of self-harming behaviors were not realized. The overall decrease in hospitalized self-harms observed during the first stage (−8.5%) [Reference Jollant, Roussot, Corruble, Chauvet-Gelinier, Falissard and Mikaeloff4] continued, although at a lower level (−3.5%). This was notably the case for middle-aged individuals in both men and women. Among 30–59-year-olds, the decreases in the number of self-harm hospitalizations during the studied period as compared to 2019 ranged from −12.6 to −15.0%. A decrease of −6% was also found in people aged 60–69 years old. Similar findings have been found in Northern England regarding primary care recorded self-harm, with a stronger decrease until August 2020 followed by a weaker decrease until May 2021 [Reference Steeg, Bojanić, Tilston, Williams, Jenkins and Carr9]. However, other locations have observed increasing trends during the first months of the pandemic [Reference Ambrosetti, Macheret, Folliet, Wullschleger, Amerio and Aguglia6, Reference Beghi, Ferrari, Biondi, Brandolini, Corsini and De Paoli10].

It is remarkable that these decreases persisted at such high rates. Indeed, results from phone surveys conducted by Public Health France [5] in a representative sample of the French adult general population (therefore, mainly middle-aged people) reported high rates of depression (18%), anxiety (23%), sleep problems (68%), and suicidal ideas (10%) at levels superior to the pre-COVID period. Similar results were found in a systematic review of studies conducted in 204 countries, demonstrating a significant increase in depressive and anxiety disorders, especially among women, since the start of the pandemic [11]. A study in Sydney, Australia, also reported a discordance between increased numbers of presentation at hospital for suicidal ideation but decreased number of self-harms during the first 15 months of the pandemic [Reference Sperandei, Page, Bandara, Reis, Saheb and Gaur12]. These findings highlight, if needed, the importance of monitoring depressive/anxiety symptoms, suicidal ideation, self-harming acts, and suicide deaths separately.

A speculative explanation may be that economic measures taken by the French government, including financial support for endangered professional activities such as restaurants or touristic places, and state-guaranteed loans for companies, may have limited the negative impact of the pandemic on working populations. Moreover, the national economy showed an unexpected rapid recovery (as early as the third trimester of 2020) in terms of unemployment and gross domestic product. Previous studies have shown that active labor market programs limit the impact on suicides during economic crises [Reference Stuckler, Basu, Suhrcke, Coutts and McKee13].

The case of adolescents and young adults

In young people, two phenomena were observed. Adolescent girls showed a large increase in self-harm hospitalizations (+27.7%), while adolescent boys and 20–29-year-old men and women showed stable numbers as compared to 2019. This is in sharp contrast to 30–59-year-old adults during the same period, and to the same age groups during the first stage of the COVID-19 pandemic (−5.0 to −22.1% in France [Reference Jollant, Roussot, Corruble, Chauvet-Gelinier, Falissard and Mikaeloff4]). The increase observed in teenage girls in France since January 2021 seems to follow the usual pre-COVID seasonal pattern that is, increasing trends during winter and spring followed by decreasing trends during the summer vacation (July–August). However, it was much more marked in 2021 than in 2019. Additional worrying observations were the increase in the use of more violent self-harming means such as hanging, jumping from height, or use of chemicals, and the increase in intensive care unit hospitalizations in female adolescents.

This temporal evolution in self-harming behaviors in adolescent females during the COVID-19 pandemic was also reported in the USA: after an initial decrease, a 26.2% increase in the number of visits to the emergency departments for suicide attempt was observed in girls aged 12–17 years. This phenomenon started in early May 2020 and was still observed in May 2021 [Reference Yard, Radhakrishnan, Ballesteros, Sheppard, Gates and Stein14]. In Manchester, England, an increase in self-harms in adolescents aged 10–17 was also observed since August 2020 [Reference Steeg, Bojanić, Tilston, Williams, Jenkins and Carr9]. In Ontario, Canada, a similar initial decline in self-harms in young people was also found [Reference Ray, Austin, Aflaki, Guttmann and Park15] followed by an increase in adolescents during the second infectious wave in September 2020–January 2021 [Reference Stewart, Vasudeva, Van Dyke and Poss16].

Explanations are only speculative so far. First, the importance of social interactions for biopsychosocial development [Reference Gifuni, Chakravarty, Lepage, Ho, Geoffroy and Lacourse17, Reference Casey, Jones and Hare18] might render young people particularly sensitive to impairments in social life, including in the domains of family, school/university, romantic relationships, and friendships. A study in Switzerland during the first lockdown showed that the main sources of perceived stress among adolescents were the disruption of social life and main activities, notably among young women [Reference Mohler-Kuo, Dzemaili, Foster, Werlen and Walitza19]. The same study also underlined high rates of excessive internet use. In France, the studied period comprised several weeks of lockdowns or curfews, and the limitation in the sizes of recreational, festive and familial gatherings that were only raised in summer 2021. Moreover, there were numerous temporary classroom closures, and closure of universities for several weeks during the 2020–2021 academic year. Finally, lockdown periods may have had negative impacts on the functioning of many families [Reference Hwang, Ipekian, Jaiswal, Scott, Amirali and Hechtman20], including high rates of domestic violence toward juveniles [Reference Stewart, Vasudeva, Van Dyke and Poss16, Reference Loiseau, Cottenet, Bechraoui-Quantin, Gilard-Pioc, Mikaeloff and Jollant21, Reference de Oliveira, Galdeano, da Trindade, Fernandez, Buchaim and Buchaim22].

This situation may have increased the risk of mental disorders among young people. Several studies have highlighted the increasing prevalence of depression in young generations before the start of the pandemic [Reference Hidaka23]. The pandemic may have exacerbated this phenomenon. For instance, a study among workers showed higher changes in severity and prevalence of depressive and anxious symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic among the youngest versus oldest workers [Reference Thomas, Lawton, Brown and Kranton24]. A literature review revealed increasing rates of depression and anxiety among adolescents since COVID-19, notably in girls [Reference Racine, McArthur, Cooke, Eirich, Zhu and Madigan25]. A Canadian survey among 12–18-year-old adolescents found a significant association between deliberate self-harm during the pandemic and (a) self-identification as transgender, nonbinary, or gender fluid; (b) not residing with both parents; and (c) psychiatric concerns or frequent cannabis use [Reference Turner, Robillard, Ames and Craig26]. It is therefore possible that the pandemic context and related effects on social life had a particularly strong impact on the mental health of younger generations.

One last speculative explanation may be that the young generations are currently exposed to high levels of uncertainty and hopelessness regarding their future, related notably to geopolitical tensions in the world and major climate changes, with limited demonstrations that things will improve any soon.

The case of older people

People aged 70-years-old and more showed no change in the number of self-harm hospitalizations during the studied period in comparison to 2019 contrary to middle-age adults. Moreover, this observation was also previously found in the first stage of the pandemic [Reference Jollant, Roussot, Corruble, Chauvet-Gelinier, Falissard and Mikaeloff4]. Literature on self-harm in older people during the pandemic remains scarce. A study of suicide -related calls to a national crisis hotline in Israel during the early months of the pandemic found a 30-fold increase in people aged 50 and more [Reference Zalsman, Levy, Sommerfeld, Segal, Assa and Ben-Dayan27].

Older people may have been particularly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic at three levels. First, they were the age group at the highest risk of COVID-19 mortality since the beginning of the pandemic and during the whole studied period. Second, they may have particularly suffered from social contact restrictions due to limited use of virtual ways of communications, the absence of professional interactions, and sometimes living alone. A study in Hong-Kong during the COVID pandemic found an association between loneliness and suicidal ideation in older people with late-life depression [Reference Louie, Chan and Cheng28]. Finally, the COVID pandemic led to an important reduction in access to care for both physical and mental health, as shown by an English population-based study [Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick and Carreira29]. This may have particularly affected this population.

Until statistics are published, it cannot be fully excluded that the numbers of suicide deaths increased during the pandemic in this age group characterized by a low suicide attempt on suicide deaths ratio [Reference Beghi, Butera, Cerri, Cornaggia, Febbo and Mollica30]. For instance, a study in Taiwan showed age differences in suicide rates during the early months of the pandemics, with an initial decrease followed by an increase in older people [Reference Chen, Yang, Pinkney and Yip31]. More research in this specific age group is urgent and vigilance is needed.

About more lethal acts

Finally, our study did not identify any impact of COVID-19 pandemic on more lethal acts (with the exception of more intensive care unit hospitalizations in teenage girls). Contrary to initial concerns during the first stage [Reference Jollant, Roussot, Corruble, Chauvet-Gelinier, Falissard and Mikaeloff4], intensive care hospitalizations decreased, and deaths in hospitals following self-harm were stable compared with 2019. This is in line with the international literature mainly showing stable or decreasing numbers of suicide deaths during the early months of the pandemic [Reference Pirkis, John, Shin, DelPozo-Banos, Arya and Analuisa-Aguilar3]. National data on suicide mortality in France are unfortunately not yet available for the pandemic period. More recent observations remain limited and continued vigilance is warranted.

Limitations

Several limitations should be kept in mind. First, this study is limited to self-harming behaviors leading to a hospitalization. It therefore does not include those leading to an emergency department visit without subsequent hospitalization or acts with no hospital presentation [Reference Jollant, Hawton, Vaiva, Chan-Chee, du Roscoat and Leon32]. However, findings are largely in line with those from calls to poison control centers for a suicide attempt [Reference Jollant, Hawton, Vaiva, Chan-Chee, du Roscoat and Leon32], and with those from emergency department visits (unpublished data from Santé Publique France) suggesting that our findings are not due to, for instance, limited bed availability. Second, it cannot be excluded that many hospitalizations following self-harm were not accurately coded as self-harm. However, this would have affected each year unless there were changes in coding procedures between 2019 and 2021, which cannot be fully confirmed or excluded. The fact that similar findings have been reported in different countries tend to support a global phenomenon. Third, hospital databases do not have extensive information, limiting the interpretation of findings. For instance, conditions of living, or professional or financial information are not found here. Additional clinical studies are required to understand the mechanisms behind the phenomena reported here, notably in terms of age and sex effects.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Ms Sarah Kabani for editing and English-language assistance.

Data Availability Statement

The PMSI database was transmitted by the national agency for the management of hospitalization data (ATIH number 2015-111111-47-33), which manages this sensitive information (https://www.atih.sante.fr/), and cannot be directly shared.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: F.J., C.Q.; Formal analysis: A.R.; Funding acquisition: C.Q.; Writing—original draft: F.J., A.R., C.Q.; Writing—review and editing: F.J., A.R., E.C., J.C.C.-G., B.F., Y.M., C.Q.

Financial Support

This study was partly funded by a grant from Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-20-COV1-0005-01) to C.Q. The funding agency had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Ethical Standards

The access to the ATIH (“Agence Technique de l’Information sur l’Hospitalisation”) hospital data platform was approved by the National Committee for data protection (registration CNIL number 2,204,633) and therefore was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written consent was not needed for this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.