Introduction

Over the past two decades, radiocarbon dates from well-stratified settlement contexts in Greece, Spain, Tunisia and Lebanon have revealed systematic discrepancies in the absolute dating of the Early Iron Age in the Mediterranean, with revised dates some 70–100 years earlier than the conventional or ‘low’ chronology (Newton et al. Reference Newton, Wardle, Kuniholm, Levy and Higham.2005; Wardle et al. Reference Wardle, Newton, Kuniholm, Todorova, Stefanovich and Ivanov2007, Reference Wardle, Higham and Kromer2014; López Castro et al. Reference Castro, Ferjaoui, Mederos Martín, Martínez Hahnmüller and Ben Jerbania2016; Gimatzidis & Weninger Reference Gimatzidis and Weninger2020; Gimatzidis Reference Gimatzidis2021; Doumet-Serhal et al. Reference Doumet-Serhal, Gimatzidis, Weninger, von Rüden and Kopetzky2023; Alagich et al. Reference Alagich, Becerra-Valdivia, Miller, Trantalidou and Smith2024). As a result, the so-called high chronology has been formulated for the Early Iron Age, with major implications for the chronology of the entire Mediterranean basin, including the later stages of the Late Bronze Age. In addition, limited radiocarbon dates from central or southern mainland Greece have so far failed to identify any divergence from the conventional chronology (Toffolo et al. Reference Toffolo2013). Although concerns were initially raised regarding potential sampling issues for dates from the north Aegean (e.g. Weninger & Jung Reference Weninger, Jung, Deger-Jalkotzy and Bächle2009: 378–80, 385–8), the large number of high-precision radiocarbon measurements on short-lived samples such as seeds and animal bones from well-defined strata at Sindos, located 14km west of Thessaloniki, have so far defied the toughest critics (Gimatzidis & Weninger Reference Gimatzidis and Weninger2020). In this article, we argue that the discrepancy between the high and conventional chronologies for the initial stage of the Early Iron Age is not the result of the misinterpretation of site stratigraphies, old-wood effects, calibration errors or sampling strategies, but rather a result of the asynchronous introduction of the pivoted multiple brush in ceramic traditions, and of the gradual development and spread of compass-drawn concentric circles (CDCCs) as a decorative motif outwards from northern Greece, specifically central Macedonia. In doing so, we establish a testable hypothesis that we hope will stimulate further work on the topic.

Despite decades of research, the origin of CDCCs and the associated Protogeometric ceramic style is uncertain. While CDCCs may be found carved into bone at the start of the Late Bronze Age (e.g. David Reference David, Roman, Diamandi and Alexianu1997; Maran & Van de Moortel Reference Maran and Van de Moortel2014: 544 and references therein), these artefacts were widely distributed across the Aegean and cannot be used to identify where, when or even if the technique was transferred onto pottery. Desborough (Reference Desborough1952: 126), a leading scholar of the Protogeometric style, in a foundational work wrote that “the evidence is not absolutely conclusive for an Athenian origin of the style”, yet this ambiguity was quickly lost in subsequent works and the view of Athenian precedency predominates today. Alternatives to this model, including an origin for CDCCs in Macedonia or Thessaly, while voiced on occasion (see Papadopoulos et al. Reference Papadopoulos, Vedder and Schreiber1998: 510–12, and references therein; Sherratt Reference Sherratt, Levy and Higham2005), have failed to find much support. Recent work on Catling type I amphorae, however, demonstrates that pioneering pottery workshops were in operation in central Macedonia during the earliest stages of the Protogeometric period (Catling Reference Catling1998a; Gimatzidis Reference Gimatzidis2020, Reference Gimatzidis and Gimatzidis2024). Likewise, recent decades have seen the publication of more substantial assemblages of Early Iron Age pottery from Macedonian sites such as Kastanas (Jung Reference Jung2002), Sindos (Gimatzidis Reference Gimatzidis2010), Toumba in Thessaloniki (Kedrou & Andreou Reference Kedrou, Andreou, Adam-Veleni and Tzanavari2017). These new data thus urge further reconsideration.

A major barrier to moving the discussion of the origin of CDCCs forward has been the scarcity of direct pottery imports between northern and southern Greece during the Early Iron Age (Catling Reference Catling1998a), preventing satisfactory relative synchronisations that go beyond stylistic analysis. The discovery of a Macedonian vase decorated with CDCCs in a Late Helladic (LH) IIIC Middle (c. 1150–1100 BC) context at Eleon, in central Greece, therefore introduces a welcome anchor between the two regional ceramic sequences and provides new support for the precedence of the Protogeometric style in the north.

While the notion that one of the defining innovations of the Early Iron Age comes from an area that has been marginalised in the main narratives of Greek history may lead to scepticism from some, this is precisely the value of undertaking the present study: to encourage a critical reassessment of knowledge production within the field of Mediterranean archaeology, to better understand how scholarly biases shape the interpretation of the archaeological record and to ensure that we improve on past models or discard them altogether. This article also highlights weaknesses in current ceramic datasets, particularly the limited number of radiocarbon dates from well-stratified Early Iron Age contexts in central and southern Greece and the small quantity of pottery provenanced through archaeometric analyses (for a recent exception, see Gimatzidis & Mommsen Reference Gimatzidis, Mommsen and Gimatzidis2024).

A Macedonian import at Eleon, Boeotia (P0275)

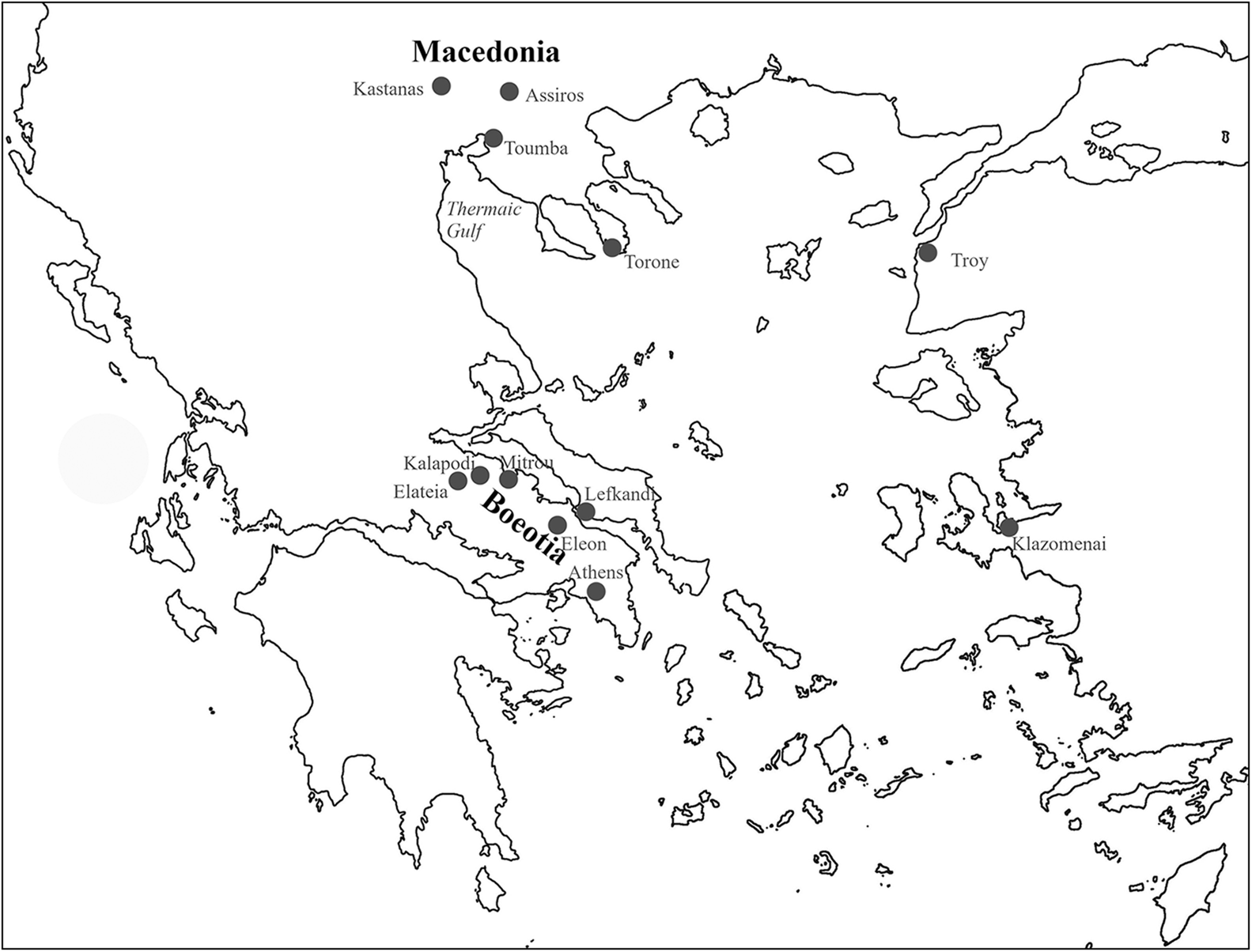

The archaeological site identified as ancient Eleon is located mid-way between Thebes and the shores of Euboean Gulf (Figure 1). The acropolis was densely occupied throughout the Late Bronze Age but activity declined sharply at the end of the twelfth century BC, only increasing again in the middle of the eighth century BC (Burke et al. Reference Burke, Burns, Charami, Damme, Herrmann and Lis2020; Lis & Van Damme Reference Lis and Damme2021; Van Damme & Lupack Reference Van Damme and Lupack2021).

Figure 1. Map of Greece showing key sites mentioned in text (figure by B. Lis).

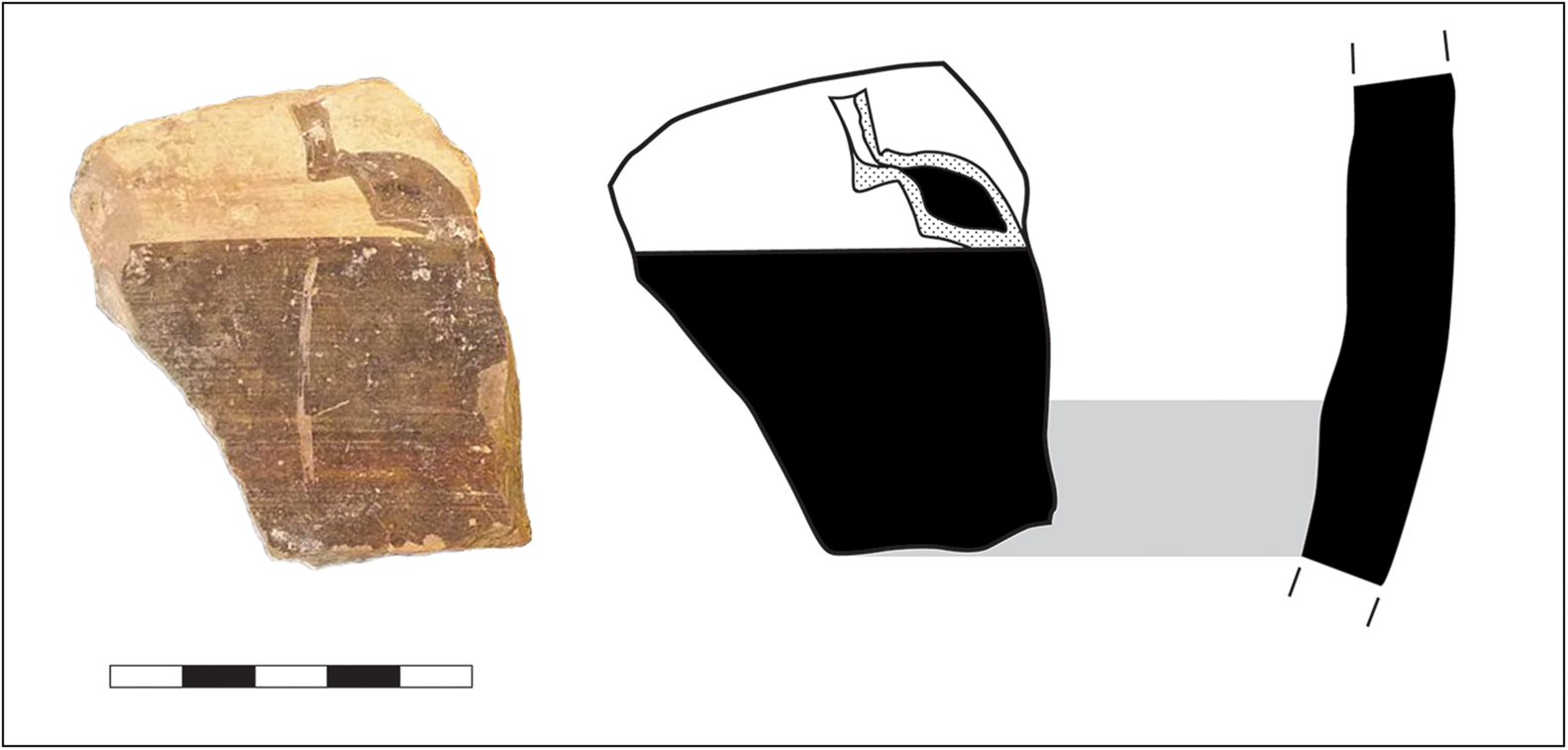

The vase from Eleon (P0275) is either a belly-handled amphora or a hydria preserving a horizontal belly handle but without definite evidence for a vertical handle (Figure 2; see also online supplementary material (OSM) Figure S1). Slightly less than half of the vase is preserved in 45 sherds, and the sharp edges of the sherds indicate rapid deposition after the vase was broken. The shoulder and belly zones present a distinct three-lined motif that is also found at Kastanas, in central Macedonia (Figure 1), where it has been called a triple horn (“dreifacher Horn”; Jung Reference Jung2002: 226). In the spaces between these streamers there are three groups of CDCCs, each consisting of three circles around a central point. The shoulder and belly zones of the vase are framed by very broad horizontal triple bands in a thin-thick-thin scheme. The preserved portion of the neck has a band at the shoulder-neck transition.

Figure 2. Reconstruction of a closed-shape amphora with CDCCs from Eleon, P0275. Scale is 50mm (drawing by T. Ross; photographs by B. Burke).

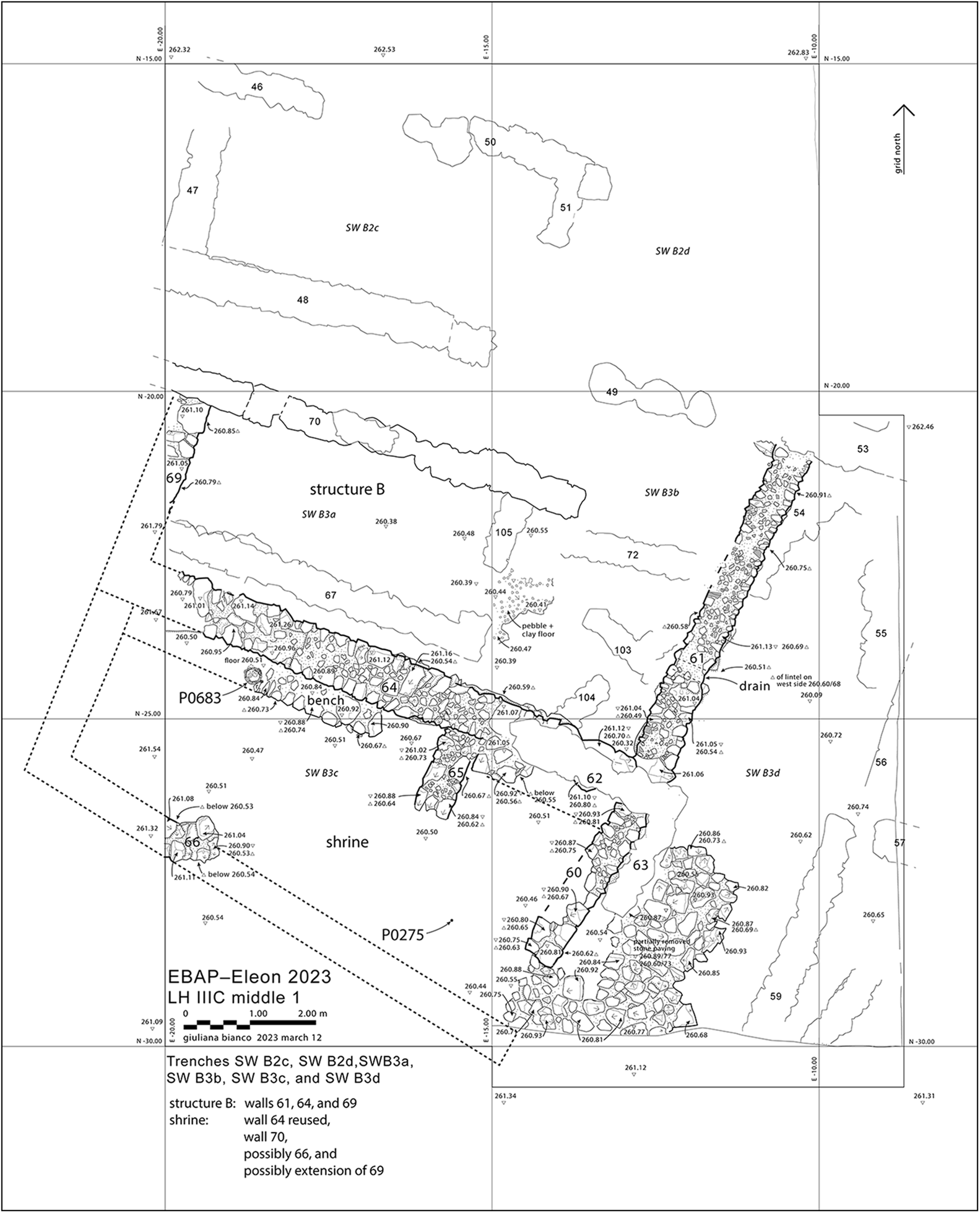

P0275 was excavated in 2013, in what is now understood to be a twelfth-century BC bench shrine (Figures 3 & 4). Excavated from 2012–2014, the western limit of the shrine remains unexplored, but the reconstructed layout consists of an antechamber and bench room with a paved forecourt providing access from the east. A portion of the southern wall of the shrine has been completely removed by later activities but the overall form is indicated by a small fragment of the original wall line projecting from the western balk of excavation trench SW B3c (Figure 4: wall 66). P0275 was discovered crushed on a clay floor (elevation: 260.52masl) in the antechamber of the shrine (Figure 4). Other pottery recovered inside the antechamber includes fragments of a bull figure, kraters (large two-handled mixing bowls for wine), kalathoi (two-handled shallow conical or flared bowls likely used for hand washing), deep bowls, carinated and semi-globular cups, and decorated conical kylikes (two-handled stemmed drinking cups) (Figure 5; OSM Figure S2). Similar material is documented above and alongside the pavement to the east of the antechamber, which produced a dense concentration of 41 wheel-made bull figure fragments. Bull figures are commonly associated with prehistoric Aegean cult sites and can be differentiated from hand-made figurines by their size (>15cm) and construction (coil and wheel creating a hollow body) (French Reference French, Hägg and Marinatos1981).

Figure 3. View of Eleon bench shrine from the south after excavation. Large scale is 1m. (photograph by M. Condell Morton).

Figure 4. Plan of Eleon bench shrine showing findspots of P0275 and P0683. Dashed lines indicate reconstructed walls (figure by G. Bianco).

Figure 5. Pictorial krater preserving the hoof of a horse, P0276, found with P0275. Scale is 50mm (drawing by T. Ross; photograph by B. Lis).

The most distinctive internal feature of the shrine is a course of fieldstones occupying the northern part of the room and forming a low bench against the south face of wall 64. A belly-handled amphora (P0683; Figures 4 & 6) was discovered still in situ where it had collapsed inwards below the level of the bench (elevation of base: 260.56masl). If the vase was inserted whole into the bench at the time of its construction, the neck of the amphora would have created an aperture within the bench into which libations could be poured. Support for this interpretation is found in a hole pierced through the base of P0683 that would have allowed liquids poured into it to seep away (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Belly-handled amphora, P0683, photographed in situ from the south (photograph by T. Van Damme).

Figure 7. Belly-handled amphora, P0683, showing pierced base. Scale is 50mm (figure by J. Vanderpool).

The date of the construction, use and abandonment of the bench shrine can be placed within the LH IIIC Middle period. A terminus post quem for its construction is established by the placement of walls 60 and 65 abutting, but not bonded with, wall 64 of structure B, which was built and abandoned during the LH IIIC Early period (c. 1185–1150 BC) (Lis & Van Damme Reference Lis and Damme2021: 70–73). That the shrine was out of use by the end of LH IIIC Middle is demonstrated by the fill that accumulated within its spaces and the presence of an architectural phase above the shrine itself, represented by walls 62 and 63. The finds post-dating the final use of the shrine include fragments of pictorial kraters, trays, conical one-handled bowls, monochrome deep bowls with narrow reserved bands on the exterior and interior, large closed shapes in White Ware fabric, and jugs with the scroll and necklace motif on their shoulders; all features that are consistent with later stages of the LH IIIC Middle and provide a terminus ante quem for the abandonment of the shrine (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Pottery found in strata above the bench shrine. Scale is 50mm (figure by T. Ross).

The bench shrine was partially disturbed by the construction of a large pit towards the end of the fifth century BC (based on pottery typology; Van Damme & Lupack Reference Van Damme and Lupack2021: 123–9), which removed the south wall. This introduced much later Archaic and Classical (sixth and fifth century BC) material. The pit containing later material was defined in the field and mostly excavated prior to the intact strata within the shrine. Despite the care taken, 12 lingering Archaic and Classical sherds making up three per cent of the total assemblage were found in two excavation units that produced joining sherds from P0275. Critically, however, a third unit overlying the floor of the shrine produced no intrusive sherds but additional joining fragments of P0275. The disturbance urges caution, so it is important to emphasise that the intrusive sherds are completely different in character from P0275 and date hundreds of years later. The most plausible interpretation of the stratigraphy is that P0275 was crushed on the floor and partially disturbed by the much later pit.

Further support for the placement of P0275 within an LH IIIC Middle stratum is the hiatus in occupation of the Eleon acropolis that spanned most of the Early Iron Age. Despite eight seasons of excavations across multiple trenches in various parts of the acropolis, not a single sherd recovered, other than the vessel under discussion, can be stylistically dated between the LH IIIC Late and the Middle Geometric period (c. 1100–750 BC) (Van Damme & Lupack Reference Van Damme and Lupack2021: 87–91). This chronological gap makes it highly unlikely that P0275 was introduced into the bench shrine after the Late Bronze Age.

Neutron activation analysis (NAA) of the chemical composition and petrographic analysis of the mineralogical composition of the clay of P0275 establish it as an import from central Macedonia (Lis et al. Reference Lis, Mommsen, Sterba and Van Damme2023: sample no. ELE018). Based on the elements identified through NAA, P0275 can be associated with a larger chemical group defined by Hans Mommsen in his database of NAA measurements in Bonn, X101. Among the other pottery from chemical group X101 are several Catling type I amphorae from Elateia, Kynos and Troy (Gimatzidis Reference Gimatzidis and Gimatzidis2024: 56, tab. 3.2), as well as additional non-amphora samples from Kastanas (Gimatzidis Reference Gimatzidis and Gimatzidis2024: 57). NAA groups X101 and Ul12, to which further samples from Kastanas and Catling type I amphorae belong, can in fact be considered a single group (Hans Mommsen, pers. comm.). Significantly, layer 12 of Kastanas provides the best parallels for the general decoration of P0275. Both the triple horn, as well as the thin-thick-thin banding, appear first in this layer (Jung Reference Jung2002: pl. 36.346; 41.388). Furthermore, the only other known vessel that combines the triple-horn motif with CDCCs is a mendable amphora at Kastanas, found joining between layers 11 and 12 but probably belonging to layer 12 based on its join distribution (Jung Reference Jung2002: 178, pl. 45.417). This supports a synchronism between the LH IIIC Middle phase at the shrine at Eleon and layer 12 at Kastanas.

Discussion and proposed model

The early date of P0275 demands a reconsideration of the origin of CDCCs and the development of the Macedonian Protogeometric style. In the following section, we present an initial model for the development and spread of CDCCs that makes use of both absolute and relative chronologies and emphasises pottery imports with known or reasonably certain provenance. Sites that lack published radiocarbon dates or comparable early imports are not included.

The origin of CDCCs and the Macedonian Protogeometric style

The new evidence from Eleon allows us to localise the origins of CDCCs in central Macedonia during the second half of the twelfth century BC. This is significant since the conventional date for this phase (c. 1170/60–1100 cal BC; Weninger & Jung Reference Weninger, Jung, Deger-Jalkotzy and Bächle2009: 416, fig. 14) agrees with the proposed start date for the emergence of the Protogeometric style in Macedonia based on the radiocarbon dates from both Assiros and Sindos (although the beginning of the style was not directly dated at either site, it is inferred to fall in the twelfth century BC; Wardle et al. Reference Wardle, Higham and Kromer2014: 6–7; Gimatzidis & Weninger Reference Gimatzidis and Weninger2020: 24). In addition, layer 12 at Kastanas, which contained the earliest Protogeometric style pottery at the site and the closest parallels to the vase from Eleon, yielded six radiocarbon dates on construction timbers. Despite the potential for the extended use and reuse of wood to create a mismatch between the felling of a tree and the deposition of the timber in the archaeological record—the old wood effect—these dates centre around an upward wiggle in the calibration curve c. 1130 cal BC (Weninger & Jung Reference Weninger, Jung, Deger-Jalkotzy and Bächle2009: 379). While the excavator and subsequent scholars have accepted a duration of 150 years for layer 12 to align with pottery typologies (from end of LH IIIC Middle to the early Protogeometric (EPG; c. 1125–975 BC); Jung Reference Jung2002: 228, fig. 80; although see Wardle et al. Reference Wardle, Higham and Kromer2014: supp. mat. 30–32 for prior criticism of this interpretation), production of CDCCs in Macedonia when Mycenaean style pottery was current in central and southern Greece would eliminate the need for this extended duration. As for the site of Toumba in Thessaloniki, the absolute dating can support both the high and conventional chronologies (Andreou Reference Andreou, Deger-Jalkotzy and Bächle2009: 24–25). Notably, phase 2A, in which Protogeometric pottery first appears, has not been directly dated.

The earliest documented CDCCs appear to be those from Kastanas layer 12 (Jung Reference Jung2002), Toumba Thessaloniki Phase 2A (Andreou Reference Andreou, Deger-Jalkotzy and Bächle2009; Kedrou & Andreou Reference Kedrou, Andreou, Adam-Veleni and Tzanavari2017) and Eleon. The vases show a clear development from the Macedonian Mycenaean style in both form and decoration. In addition to CDCCs, thin-thick-thin banding and the triple-horn motif appear to be synchronous developments (Figure 9). At these three sites, CDCCs were applied both to open and closed shapes, including amphorae, hydrias, kraters and deep bowls. In some cases, CDCCs are placed as secondary motifs or substitutions for spirals, evidencing experimentation by local potters. Critically, the earliest pieces have only 2–5 concentric circles around a central pivot documenting a simpler form of the multiple brush used to produce the motif.

Figure 9. Earliest Macedonian Protogeometric style pottery from Toumba Thessaloniki and Kastanas. Scale is 50mm (Toumba: 1. Kedrou & Andreou Reference Kedrou, Andreou, Adam-Veleni and Tzanavari2017: 436, fig. 6 KA 2958; 2 & 3. Andreou Reference Andreou, Deger-Jalkotzy and Bächle2009: 40, fig. 15.5–6; 6 & 7. Andreou Reference Andreou, Deger-Jalkotzy and Bächle2009: 40, fig. 15.8–7; Kastanas: 4 & 5. Jung Reference Jung2002: pl. 28.293–294; 8. Jung Reference Jung2002: pl. 41.388; 9. Jung Reference Jung2002: pl. 45.417; 10 & 11. Jung Reference Jung2002: pl. 40.386–387; 12 & 13. Jung Reference Jung2002: pl. 41.389–390).

Catling type I amphorae and their dispersal

A possible mechanism for the spread of CDCCs is the appearance and wide circulation of the earliest transport amphora in the Aegean; a neck-handled amphora with two sets of CDCCs placed in the shoulder zone known as Catling type I amphorae (Catling Reference Catling1998a). These amphorae first appear in central and eastern Greece in the EPG according to the conventional chronology, but pre-date the appearance of locally produced Protogeometric style pottery at many sites (Catling Reference Catling1998b: 155–64). The recent confirmation of the Macedonian origin of these amphorae localises their earliest production around the Thermaic Gulf (Gimatzidis Reference Gimatzidis and Gimatzidis2024: 54–58, tab. 3.2).

We can trace further developments of the Macedonian Protogeometric style in layer 11 at Kastanas (Jung Reference Jung2002). During this phase, the average number of concentric circles around the central pivot increases, concentric semicircles appear for the first time, a panel of vertical wavy lines separating CDCCs is introduced (layer 11/12, No. 419 in Jung Reference Jung2002) and closed shapes shift from globular or piriform profiles towards more ovoid or biconical ones. These features coalesce in the Catling group I amphorae.

The relative chronology of this development appears to overlap with the regional ceramic styles variously identified as LH IIIC Late (c. 1100–1050 BC) and Submycenaean (c. 1050–1025 BC) in central and southern Greece (on the validity of the terms and their proposed absolute chronology, see Lis Reference Lis, Deger-Jalkotzy and Bächle2009; Papadopoulos et al. Reference Papadopoulos, Damiata, Marston and Gauss2011: 187–98). At Torone, an Attic Submycenaean-style skyphos (a two-handled bowl) was found in association with a Catling type I amphora in the pyre debris of Tomb 101 (Papadopoulos et al. Reference Papadopoulos, Damiata, Marston and Gauss2011: 197, fig. 8, 198). Another Catling type I amphora comes from Tomb XXXIX at Elateia, where it was found paired with an LH IIIC Late amphora with a scroll motif on the shoulder (Deger-Jalkotzy Reference Deger-Jalkotzy and Froussou1999: 200–1, fig. 11; Deger-Jalkotzy & Gimatzidis Reference Deger-Jalkotzy, Gimatzidis and Gimatzidis2024: 207–8). In central Greece and western Turkey, the earliest stratified settlement deposits containing CDCCs at Kalapodi, Kynos, Mitrou, Troy and Klazomenai consist of Catling type I amphorae together with a lot of late LH IIIC style pottery (Jacob-Felsch Reference Jacob-Felsch and Felsch1996; Aslan Reference Aslan2002; Aytaçlar Reference Aytaçlar and Mustaka2004; Lis Reference Lis, Deger-Jalkotzy and Bächle2009: 204–9; Kounouklas Reference Kounouklas2011: 193–209, esp. 200–1). Previous scholarship has attributed this to extreme ceramic conservatism and assigned respective settlement phases to the Protogeometric period based solely on the appearance of CDCCs (Lis Reference Lis, Deger-Jalkotzy and Bächle2009). As the present study demonstrates, however, this more likely represents a period when Macedonian pottery decorated with CDCCs began to spread to other regions through the maritime trade of Catling type I amphorae, but before Protogeometric style pottery started to be produced locally.

Recent discoveries from Athens and Klazomenai validate this model. A fragment belonging to a closed-shape ceramic vessel decorated with CDCCs on the shoulder, made in a fabric compatable with a Macedonian origin and attributable to a Catling type I amphora, was identified in the closed fill deposit of well O 8:5 at the Athenian Agora (personal observation B. Lis). This well belongs to the final Late Bronze Age contexts at the Agora, immediately preceding the appearance of locally produced Early Protogeometric style pottery in Athens. At Klazomenai, building 4—the earliest structure to produce Catling type I amphora fragments at the site—contained vessel fragments dated to LH IIIC Late, including a belly-handled amphora or hydria with a Euboean provenance securely established by recent NAA work (Vaessen & Ersoy Reference Vaessen, Ersou and Gimatzidis2024: 220, 226, fig. 7.7). This amphora finds a close parallel in a Euboean Submycenaean vase from pyre 3 of the Skoubris cemetery (Popham et al. Reference Popham, Sackett, Themelis, Popham, Sackett and Themelis1980: 135, no. 3.1, plates 90, 112). Thus, Catling type I amphorae appear to precede the local production of CDCCs in both Attica and Euboea.

While the identification of an Attic krater decorated with CDCCs in Kynos phase 5, together with Macedonian CDC-decorated amphorae (Deger-Jalkotzy & Gimatzidis Reference Deger-Jalkotzy, Gimatzidis and Gimatzidis2024: 193) could be used to argue against the synchronisation proposed here, it is important to note that this phase is probably protracted. The preceding phase 6 is firmly dated to LH IIIC Late, and thus phase 5 covers both Submycenaean (as originally assigned in Kounouklas Reference Kounouklas2011) and EPG periods (based on the Attic krater), and perhaps also MPG since high conical feet (e.g. Kounouklas Reference Kounouklas2011, no. 198, fig. 172) are not found in central Greece prior to that stage (Lemos Reference Lemos2002; Lis Reference Lis, Deger-Jalkotzy and Bächle2009: 208).

Absolute dates confirm that the development of the Catling type I amphora took place in the early- to mid-eleventh century BC. Support for this date comes from a Catling type I amphora from Assiros dated through a suite of associated short-lived radiocarbon samples on animal bone and carbonised seeds, as well as dendrochronological wiggle match (1095–1070 BC at 95.4%; date modelled in OxCal 4.2.2, using the IntCal13 calibration curve; Wardle et al. Reference Wardle, Higham and Kromer2014), and from radiocarbon samples of pyre charcoal associated with the cremation in Tomb 101 at Torone (1130–1019 BC at 95.4%; date modelled in OxCal 4.1.3, using the IntCal04 calibration curve; Papadopoulos et al. Reference Papadopoulos, Damiata, Marston and Gauss2011: 198–9, figs. 8 & 9, tabs. 1 & 2). As the latter context contained an Attic Submycenaean bowl, it is worth stressing that this date is in agreement with the proposed dates for the Submycenaean style in Attica, Corinth and Euboea (Toffolo et al. Reference Toffolo2013). Thus, it is the dates of the Macedonian Catling group I amphorae and not the Attic Submycenaean style that require upwards revision. Moving up the start date of Catling I type amphoras, however, does not exclude an overlap with Attic EPG, as Catling originally proposed (Reference Catling1998b: 176).

The trade of Catling type I amphorae appears to have increased interest in CDCCs and led to the widespread adoption of the pivoted multiple brush. At present, it is difficult to map the dispersal of this innovative technology but the Argolid, Euboea and Attica were among its early adopters. What distinguishes each of these three regions from the Thermaic Gulf, however, is that their earliest locally produced Protogeometric style pottery already uses an advanced form of the pivoted multiple brush, indicating that the transfer of technology involved in the use of this device took place after the experimental phase outlined above. For instance, at Athens, EPG-style vases have no less than five, and up to eight, concentric circles around the central pivot. Likewise, at Lefkandi, the earliest concentric circles, assigned to the Euboean Middle Protogeometric (c. 1000–950 BC; now considered to overlap in part with the Attic EPG: Catling & Lemos Reference Catling and Lemos1990: 94) range from 3–11 circles with a heavy preponderance of vessels with 6–11.

If one accepts that the Attic EPG style succeeds the Attic Submycenaean (e.g. Ruppenstein Reference Ruppenstein2007), then the absolute dates for its start must be later than both the appearance of CDCCs in central Macedonia and the initial production of Catling type I amphorae. Following the model presented here, we also recognise that the earliest Athenian-produced neck-handled amphorae decorated with concentric circles directly imitate Catling type I amphorae (Figure 10). Similarly, a Proto-White Slipped Ware belly-handled amphora from Salamis on Cyprus can also be seen as modelled on Macedonian rather than Attic prototypes (contra Desborough Reference Desborough and Yon1980). While this model could be disproved by new absolute dating of the Attic EPG style, the sparse dates available at present suggest that the Attic Early Protogeometric should date no earlier than c. 1025 cal BC (Toffolo et al. Reference Toffolo2013).

Figure 10. Comparison of Catling type I amphorae (1–4) and Transitional and EPG neck-handled amphorae from Athens. Scale is 50mm (Assiros: 1. Wardle et al. Reference Wardle, Newton, Kuniholm, Todorova, Stefanovich and Ivanov2007: 493, fig. 6; Klazomenai: 2. Aytaçlar Reference Aytaçlar and Mustaka2004: 21, fig. 4.1; Troy: 3. Lenz et al. Reference Lenz, Ruppenstein, Baumann and Catling1998: 215, pl. 4; Elateia: 4. Deger-Jalkotzy Reference Deger-Jalkotzy and Froussou1999 200, fig. 11b; Athens: 5–8. Dalsoglio Reference Dalsoglio2020: 163, pl. 19).

Chronological implications

Table 1 presents the results of the present analysis and the conventional dates for the introduction of the Protogeometric style in various regions of Greece. With the exception of our suggestion that the boundary between layers 11 and 12 at Kastanas deserves to be reconsidered, the impacts of our study are mainly limited to the north Aegean and have no further impacts on previous synchronisations or stratigraphic sequences. We admit that much work remains to further validate or refute the dates suggested here, but the model can be tested, challenged and ultimately improved by the introduction of new data.

Table 1. Proposed absolute dates for Macedonian Protogeometric style and their relationship to other regions.

Conclusion

At the end of his presentation of the Attic Protogeometric style, Desborough (Reference Desborough1952: 126) wrote: “If the Attic Protogeometric technique has its origins elsewhere, then signs of it must be visible in some other demonstrably earlier context.” This article provides relevant data supporting the earlier development of CDCCs in Macedonia from multiple contexts across the Aegean region, including radiocarbon dates that place the emergence of this motif in the region of the Thermaic Gulf during the twelfth century BC and a recently discovered Macedonian vase from Eleon found in association with LH IIIC Middle style pottery. The proposed model documents a period of experimentation that gave way to increasingly complex groups of circles and designs, and emphasises that the earliest imported Protogeometric style pottery in central Greece, western Anatolia and even the Athenian Agora is Macedonian, not Attic, in origin. Combined with the almost complete lack of Attic EPG exports (see Catling Reference Catling1998a), this observation makes it increasingly difficult to accept that Athens played a major role in instigating the initial development of other regional styles.

When viewed within the context of the EPG style in Athens, it is not surprising that CDCCs would originate from another area entirely. In a study of the Protogeometric Aegean, Lemos (Reference Lemos2002: 14) highlights that the ceramic repertoire of EPG Athens was “enriched by the introduction of unusual or unique vases and shapes: the flask; the bottle; the ring vase; and others” and goes on to indicate that these “probably copy imported vases from Cyprus and Crete”. Ruppenstein (Reference Ruppenstein2007), in defining the transition from the Submycenaean to EPG style, similarly highlighted the receptivity of Athenian craftspeople to external influences. The results of the present analysis fit comfortably alongside these observations and logically suggest that the first CDCCs in Athens also copied imported vases, in this instance from Macedonia. They further highlight the prevailing Athenocentrism that characterises scholarly narratives of the Early Iron Age in Greece and urge re-evaluation of the relative importance of Athens in Aegean trade networks prior to the tenth century BC.

The present study serves as a call for more scientifically informed research into the origins and spread of the Protogeometric style, for example through the combination of high-precision radiocarbon dates and archaeometric provenancing of pottery. While our proposal has the potential to explain the discrepancies between the high and low chronologies through the tenth century BC, it does not resolve subsequent issues with Middle and Late Geometric styles for which Attic imports at Sindos have been directly dated. This again highlights the need for an integrated methodology and further data.

Finally, the results of this research highlight a growing problem in archaeological practice around the tendency to perceive ceramic styles as sequential. The chronological discrepancy in dating the beginning of the Protogeometric period could have been resolved, even without the Eleon vessel, if scholars were more willing to accept that different pottery styles, such as Mycenaean, Submycenaean and Protogeometric in Greece, can be contemporaneous (e.g. Desborough Reference Desborough1972: 29–49; Rutter Reference Rutter and Betancourt1978) and that particular stylistic novelties can appear first in ‘peripheral’ areas, with significant delays prior to their adoption elsewhere. This, however, undermines the fundamental concept of the ‘type fossil’ that is the backbone of many of our synchronisms. And while a partial solution to the problem would be to credit Macedonia with the invention of CDCCs but Athens with the Protogeometric style, we believe that a more appropriate and widely applicable convention is to add a geographical denomination to the name of the style. In this way, the Macedonian Protogeometric style can be properly appreciated and investigated in its own right.

Acknowledgements

We thank the directors of the East Boeotia Archaeological Project, Brendan Burke, Bryan Burns and Alexandra Charami, as well as the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports and the Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia for their support.

Funding statement

This study has been funded through grants from the National Science Centre, Poland (no. 2016/21/D/HS3/02696), and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (no. 430-2022-00390).

Online supplementary material (OSM)

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.144 and select the supplementary materials tab.