At first look, Vietnam might seem to represent the apex of Cold War congressional activism. On no other foreign policy issue between 1947 and 1989 did Congress – especially the Senate – devote so much effort both to reining in executive power and to challenging the principles underlying Cold War foreign policy. In another respect, however, the legacy of Congress and Vietnam is one of failure. The legislature largely deferred to the executive during the Johnson and Nixon administrations, after forfeiting its greatest chance to shape Vietnam policy by paying insufficient attention to Southeast Asia before the US military commitment significantly escalated.

The congressional response to the conflict is divided into three eras. Until 1964, members of Congress approached Vietnam mostly as one of several controversial foreign aid issues, rather than as a burgeoning military intervention or a foreign policy crisis. This approach peaked in 1963, when Congress devoted considerable attention to Southeast Asia. The second period, from 1964 through 1968, featured deep divisions on partisan, institutional, and ideological grounds. Liberals – mostly Democrats and mostly in the Senate – sought to use the institutional power of Congress to force Lyndon Johnson to modify his Vietnam policy but struggled to perform an effective oversight role. Between 1968 and the collapse of South Vietnam in 1975, the response to Vietnam functioned as part of a broader congressional challenge to executive primacy in international affairs, with the legislature mostly employing the power of the purse to accomplish its aims. Even here, however, Congress proved less successful in contesting executive power on Vietnam issues than regarding policies elsewhere.

The most influential works on Congress and Vietnam remain biographies of key members – especially from the Senate – who shaped the institution’s response to the war. The role of Republican senators, traditionally understudied, is the focus of an important book from Andrew Johns. There are a few institutional histories of Congress and foreign policy that cover the conflict. Works on the House of Representatives – either individual biographies or institutional studies – remain much rarer.Footnote 1

The Foreign Aid Revolt

One of the first senators to express consistent concerns with US policy toward Vietnam was Allen Ellender (D-Louisiana). A protégé of Huey Long, Ellender’s foreign policy beliefs combined a skepticism toward overseas spending, a generic hostility to communism, and a racist sense that nonwhite peoples could not effectively govern themselves. This combination prompted him to criticize the Eisenhower administration’s decision to extend economic and military assistance to Ngô Đình Diệm’s newly formed regime in South Vietnam. “Personally,” he recalled a decade later, “I went on record as far back as 1954 against U.S. involvement in Viet Nam, and advised President Eisenhower against it.” In 1957, the Louisiana senator suggested the United States was trying “to do too much too fast,” citing South Vietnam as an example of where it “appears obvious that our [foreign] aid effort … is being used to fill the coffers of the Vietnamese government.”Footnote 2

No one would confuse Ellender with a deep thinker on international affairs. He was best known for annual international tours, purportedly inspecting US foreign aid projects for wasteful spending, which he would then promote with amateurish home-made movies upon his return to Washington. The New York Herald-Tribune joked that his efforts demonstrated that “every American possesses among other freedoms the freedom to make a fool of himself.”Footnote 3

Despite Ellender’s reputation as a lightweight, he correctly recognized Vietnam as an example of foreign aid abuses and interpreted the problem as a foreign aid issue rather than as a military intervention. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, senators from various positions on the ideological spectrum shared their colleague’s concerns. They stand out because, as a general matter, the Senate during this period supported the foreign aid program. In 1959, for example, J. William Fulbright (D-Arkansas) criticized “defense support and special assistance, such as is involved in Viet Nam.” Two years later, Albert Gore, Sr. (D-Tennessee) questioned what “more of the same thing would accomplish” in terms of US military aid to South Vietnam. Wayne Morse (D-Oregon) likewise cited “the cumulating evidence that the Government of South Vietnam is not a democratic government.”Footnote 4

The most significant such move came in December 1962, when Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (D-Montana) led a Senate delegation to South Vietnam. The former history professor, generally considered among the Senate’s most knowledgeable members on East Asian matters, had tended to support the regime of Diệm, a fellow Catholic. But he returned from the 1962 trip convinced that the United States needed to “make crystal clear to the Vietnamese government and to our own people that while we will go to great lengths to help, the primary responsibility rests with the Vietnamese.” Privately, Mansfield suggested “that our chances may be a little better than 50-50.” He released a report questioning the effectiveness of US aid to South Vietnam; after all, he noted, “seven years and billions of dollars later” since his previous visit to the country, he heard “the situation described in much the same terms.” The head of the British Advisory Mission to Vietnam relayed the report’s “depressing effect” in the field.Footnote 5

The US role in South Vietnam gradually evolved from an economic aid initiative in the mid-1950s to a mixed economic and military aid program in the late 1950s, to a military aid program accompanied by a small military commitment during the Kennedy years. But because each of these structures remained, at its core, a foreign aid program, it required an annual congressional authorization and appropriation, funded through foreign aid rather than the Pentagon budget – ensuring a major role for Representative Otto Passman (D-Louisiana), whose Foreign Operations Subcommittee had jurisdiction over the foreign aid program’s funding level. Dubbed “Otto the Terrible” by foreign aid supporters, the Louisiana congressman considered the entire program both wasteful and unnecessary.Footnote 6 And he reflected broader attitudes toward foreign aid in the House.

Quite apart from the specifics of his agenda, Passman was an extraordinarily difficult person with whom to interact. (Lyndon Johnson, fuming that the congressman had “a real mental problem,” doubted Passman’s having acquired much “information or knowledge or wisdom” in “the swamps of Louisiana.”) Passman rejoiced in “the limelight” on foreign aid, boasting of his ability, despite having dropped out of school at a young age, to perform the task: “You don’t need a diploma to do this. All you need is common sense.” As he informed one foreign aid official, “I don’t smoke and I don’t drink. My only pleasure in life is kicking the shit out of the foreign aid program of the United States.” Described by reporter Tim Creery as “cadaverous, twitchy, and intense,” Passman spent time on few other legislative issues, and his knowledge of the intricacies of the aid program, unsurpassed in Congress, often exceeded that of senior foreign aid administrators who had only served a few years in their position. Peace Corps Deputy Director William Haddad summarized the general sentiment of officials from three administrations: “Passman’s a sick, sick man.”Footnote 7

Between 1954 and 1962, these two patterns – Passman’s vitriolic hostility to foreign aid in general, though without a specific focus on Vietnam, and the sporadic concerns of Senate Democrats (liberals as well as conservatives) with the execution of the Vietnam aid program – did not intersect. During these years, despite his power in the House, Passman could not obtain a large enough reduction in the program to affect the Vietnam aid package. Senate liberals were more repelled by Passman’s anti-aid posture than by individual aid packages that contradicted their ideals. That situation changed in 1963. Passman was at the zenith of his power, and a backlash among Senate liberals against aid to military regimes (mostly in Latin America) produced a wider reconsideration of foreign aid. US News & World Report dubbed the situation as the “foreign aid revolt,” and, at least in theory, it threatened the underpinnings of the US role in South Vietnam before a substantial number of US combat troops were stationed there.Footnote 8

In fiscal year 1963, around one-eighth of the entire foreign aid budget, or nearly $500 million, went to South Vietnam. As the year began, the White House feigned at cooperation with Passman, but neither side had much interest in working together. In the House, Passman prevailed, securing a $1.728 billion reduction in Kennedy’s request for a $2.802 billion appropriation. The president lamented that the cuts had gotten into the “deep muscle” of the program. National Security Council (NSC) staffer Robert Komer worried that unless the Senate reversed Passman’s cuts, the United States would not “be able to sustain the kind of effort in Southeast Asia which is now costing us well over half a billion [dollars] a year.”Footnote 9

Unfortunately for the administration, as the foreign aid bill moved to the Senate, adverse diplomatic and military developments – a political crisis caused by tensions with neutralist Buddhist factions, which culminated in the self-immolation of a Buddhist monk, the military setbacks for Diệm’s forces, the diplomatic tensions between Diệm and Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, and the internal divisions over policy within the Kennedy administration – highlighted attention on Vietnam. Speaking for several of his colleagues, Stephen Young (D-Ohio) described the Agency for International Development (AID) as “terrifically overstaffed” in Southeast Asia, making the region an obvious target for funding cuts. Ernest Gruening (D-Alaska) deemed the situation “a disaster … a trap of our own making.” The Senate’s most searing indictment of Kennedy’s Vietnam policy came in closed committee hearings, from Albert Gore. While conceding that he was not “an expert on the situation in Vietnam,” Gore suggested that the Buddhist crisis had given the United States a “legitimate excuse” to cut its losses and withdraw. Even though such a move likely would yield a communist victory, “from our expenses there it might be good riddance.”Footnote 10

While Gore challenged the administration’s intellectual rationale for Vietnam, the best-known Senate overture in 1963 came from Idaho Senator Frank Church. Operating from the premise that “the present government” might not be the “kind of regime” that could “conduct successfully the war effort,” Church suggested diplomatic protests to Diệm, keeping in mind that if the Saigon regime were recalcitrant, “we are in a position to go further withholding certain kinds of aid.” The Idaho senator introduced a sense of the Senate resolution affirming that “unless the government of South Vietnam abandons policies of repression against its own people and makes a determined and effective effort to regain their support, military and economic assistance to that government should not be continued.”Footnote 11 While the Senate never formally voted on the measure, similar wording eventually was incorporated into the text of the 1963 foreign aid bill.

On paper, then, it appeared as if Congress might significantly restrict the Vietnam intervention. But limitations existed as to how far critical senators were willing to go. Declining to follow his report’s arguments to their logical conclusion, Mansfield asserted in summer 1963 that “we are stuck” with the involvement “and must stay with it whatever it may take in the end in the way of American lives and money and time to hold South Viet Nam.” Gore, meanwhile, assured Kennedy officials that he had deliberately confined his criticism to private comments, and that he had “made no public statement on the current crisis in Vietnam. None whatsoever.” And while Church’s sense of the Senate resolution was the strongest formal congressional offering on South Vietnam during the Kennedy years, it was hardly a bold challenge to executive authority. The Idaho senator, who described himself as “fully in accord” with Kennedy’s goals in South Vietnam, closely coordinated with administration officials. His efforts also deflected attention from a far more ambitious proposal, from Kenneth Keating (R-New York), for a comprehensive Foreign Relations Committee investigation of the South Vietnam aid program.Footnote 12

During the Cold War, Congress could, and often did, influence foreign policy through informal means, procedural gambits, or indirect committee or subcommittee pressure. So the initiatives described above were far from insignificant. But they also were notable for what they failed to accomplish. Unlike other aspects of the 1963 foreign aid revolt, congressional action on Vietnam avoided funding cuts or amendments that restricted policy, and even the Church resolution reflected a more moderate parliamentary strategy than the Keating amendment, which the administration opposed.

Two reasons explain the generally passive role Congress took toward Vietnam in the foreign aid era. First, as late as 1963, most members of Congress – even those who spent considerable time on international issues – knew relatively little about Vietnam. (Mansfield, an exception to this limitation, focused on his tasks as majority leader, and participated only sporadically in foreign aid hearings.) Hubert Humphrey (D-Minnesota) typified the problem of legislative ignorance, admitting in November 1963 that he was “really not very well informed” about “such a confusing area.” Closed Foreign Relations Committee hearings often served as a kind of travelogue, with senators musing about possible (if unknown) comparisons between Vietnam and Thailand or Malaya. Comments about substance were even odder. Based on a single trip to South Vietnam in 1959, Bourke Hickenlooper (R-Iowa), the Foreign Relations Committee’s ranking Republican, dismissed reports that Diệm had mistreated Buddhists, and pressed the CIA to uncover evidence that the Buddhist priests who engaged in self-immolation really “were subject to drugs or other dulling or deadening devices, hypnosis or other types of human control.”Footnote 13

This level of congressional ignorance sharply contrasted with Latin America, with which many members of the upper chamber – on both sides of the issue – had been deeply engaged in policy since the late 1950s. As the Senate considered the 1963 bill, senators, already with a relatively limited amount of time for floor debate on foreign aid, tended to focus on the region of the world they knew best (Latin America) and steered clear of areas with which they were less comfortable.

Second, while legislators could have taken the time (as many eventually did) to familiarize themselves with Vietnam, in 1963 other regions of the world yielded more fruitful opportunities to criticize Kennedy’s foreign aid policies. As a result, legislative tactics dictated that senators (and, critically, Passman) look beyond Vietnam in their attacks on the foreign aid program.

In the House, for instance, Vietnam represented perhaps the only aspect of the foreign aid program in which Passman knew less than the witnesses he was questioning. He (and his staff) combed through often-obscure publications, seeking unreported or underreported quotations from executive branch officials revealing waste in the program. That these quotations were “generally out of context,” as a Kennedy administration study noted, did not minimize their effectiveness. Passman browbeat low-level witnesses, looking for embarrassing statements that could be exploited on the House floor. He overwhelmed witnesses with a barrage of figures, hoping to extract incorrect answers that he then could use to challenge the administrators’ expertise.Footnote 14

During subcommittee hearings about South Vietnam, however, Passman confronted not the mid-level bureaucrats to which he was accustomed but instead Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, and AID administrator David Bell. A “gotcha” moment seemed unlikely, while critiquing aid to South Vietnam threatened his standing with anticommunist conservatives. While Passman did not avoid Vietnam entirely in 1963, he had sufficient alternative grounds for attacking the foreign aid program to stay relatively clear of Southeast Asia.

For Senate critics of foreign aid, events in Vietnam also were an awkward fit, though for ideological rather than tactical reasons. In the early 1960s, with events in Latin America providing the frame of reference, safeguarding existing democracies, especially from the threat of military coups, was the chief focus of Senate liberals.Footnote 15 This is why the Alliance for Progress, which funneled military aid that Latin American generals then used to oust democratically elected regimes, aroused such concern. Diệm, by contrast, did not fit neatly into a protect-democracies paradigm. He clearly was not a democrat. Nor, however, had he come to power via a military coup. So for protect-democracy liberals, critiquing aid to his regime – as opposed, say, to the Dominican Republic or Honduras after 1963 military coups in those nations – carried less ideological appeal.

Even the November 1963 coup that toppled Diệm produced disparate reactions in Congress. Gore (once again, in private) recommended severing ties with South Vietnam, lest “this constant and repetitive identity of the United States with military coups and repressive regimes … erode the image of the United States in the world.” Church, on the other hand, welcomed “the thing that I certainly had hoped for, because it was becoming increasingly evident the incompetence and corruption of this regime was going to lose the war against the Communists.”Footnote 16

In short, amidst a complex debate about the future ideological and financial direction of foreign aid, critics of the program, from both the right and the left, searched for particular issues they could exploit to demonstrate the wisdom of their overall critique. Since the South Vietnam aid package was less on-point for these critics than aid to other regions, it received less attention than it deserved.

The lengthy Senate floor debate ensured that the foreign aid bill had not cleared Congress by the time of Kennedy’s assassination. This delay theoretically allowed Congress to reevaluate conditions in Vietnam in the aftermath of the coup. No such examination occurred. Instead, the final stages of the 1963 foreign aid bill fight revolved around a battle between Passman and Lyndon Johnson over the funding level (Passman prevailed) and the new president’s frantic and ultimately successful efforts to block a politically inspired amendment to force him to publicly report whenever he authorized emergency aid to a nation in the Eastern Bloc. Reflecting on Passman’s conduct with Texas Congressman Jack Brooks, Johnson bitterly concluded, “If I ever walk up in the cold of night and a rattlesnake’s out there and about ready to get him, I ain’t going to pull him off – I’ll tell you that.”Footnote 17

At the time, it might have seemed that Congress would have ample opportunity to return to Vietnam and examine the issue more closely. But instead, the next two times Vietnam came before Congress, it did so in crisis situations – the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964 and an emergency defense appropriations measure in 1965. The 1963 foreign aid debate thus would provide Congress with its best opportunity to fully explore Vietnam policy before US troops were irrevocably committed to the region. In the end, it failed to do so, poorly serving both the public and itself.

The Limits of Oversight

The first high-profile congressional vote on Vietnam policy, the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, came in August 1964. The first high-profile vote on funding for the conflict occurred the following year, for a supplemental defense spending measure. In both instances, the parliamentary situation (declining to support a retaliatory attack that had already occurred, declining to appropriate money for troops that were in the field) discouraged congressional assertiveness. And in both instances, Congress approved the president’s request with only a handful of dissenting votes.

These vote tallies did not accurately reflect the state of opinion on the war in Congress, at least in the Senate. Almost without exception, during late 1963 and early 1964 Senate Democrats opposed widening the war, while their Republican colleagues, sensing a campaign issue against the popular new president, advocated a more aggressive approach to Vietnam. Bourke Hickenlooper typified the GOP’s public rhetoric when he claimed that the Kennedy–Johnson policy meant that “our fighting man is fighting in effect with one arm tied behind his back, under artificial restrictions.” National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy would later complain that, on Vietnam, Republican legislators sought “to have it both ways,” criticizing Johnson’s policies while offering only an all-out war in their place.Footnote 18

Despite minimal enthusiasm for the war among Senate Democrats, most also were inclined to give the Johnson administration the benefit of the doubt, and in the first seven months of the new administration, congressional activity on Vietnam waned. The vacuum was filled by the two most radical members of the Senate caucus, who delivered a series of speeches demanding a reversal of US policy in the region.

In September 1963, Ernest Gruening privately remarked that if his son were killed in Vietnam, “I would not feel that he was dying for the defense of my country.” He made these sentiments public in a March 1964 Senate address (surprising colleagues, the New York Times reported, “by his choice of strong words”) – while also recommending withdrawal, given that defeat was “ultimately inevitable, in impossible terrain, for people who care not.” Morse expressed similar sentiments in a series of speeches deeming the conflict an undeclared war that violated the Constitution.Footnote 19

When NSC staffer James Thomson surveyed sentiments in the Senate in spring 1964, he discovered that “although Morse and Gruening appear to have made no admitted converts during this period, they have encountered little rebuttal from their colleagues,” with “a growing number of Senators … privately sympathetic with the Morse–Gruening position.” That list included several Southern conservatives. At the same time, however, the duo’s rhetoric made it politically problematic for other senators to fully endorse their position. Their willingness to publicly resist did have some impact. In May 1964, when CIA Director John McCone predicted easy passage of a congressional resolution expressing blanket support for the administration’s handling of Southeast Asian affairs, McGeorge Bundy replied, “Convert Morse first.”Footnote 20

If Morse and Gruening upped the price for the administration introducing a general resolution of support, this did not mean the idea was rejected out of hand. Indeed, in June 1964, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian Affairs William Bundy deemed the question of whether to offer such a resolution an “immediate watershed” issue. An excuse came on August 2, 1964. After a US-supported South Vietnamese naval raid on its coast, North Vietnamese forces fired on the USS Maddox, which was inside North Vietnam’s territorial waters. The Defense Department almost immediately doubted reports of a second attack two days later, but the administration failed to communicate these concerns to Congress. Instead, Johnson promoted the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, whose text approved the retaliatory raids he already had launched against North Vietnam and authorized him to “take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.”Footnote 21

A bill to grant the president advance commitment to use force was hardly a novel tactic. Eisenhower had secured two such resolutions (to respond to the Taiwan Straits Crisis in 1955 and events in the Middle East in 1957) and Kennedy one (during the Cuban Missile Crisis). In Johnson’s case, however, political concerns also furthered the idea of a resolution, as a way of neutralizing GOP presidential nominee Barry Goldwater’s attacks on administration weakness in Southeast Asia.

The presence of US troops in Southeast Asia and the measure’s explicit endorsement of armed retaliation that already had occurred gave the administration insurmountable leverage when Congress considered the bill. No negative votes came in the House, where the only major criticism, offered by Ed Foreman (R-Texas), focused on Johnson’s decision to announce the retaliatory raids before rather than after they had occurred. Citing the president’s desire for an announcement to occur before midnight Eastern Time, the El Paso congressman accused him of “shooting from the lip.”Footnote 22

In the Senate, as expected, only Morse and Gruening voted no. Morse, receiving word from Pentagon contacts that the second attack likely never occurred, denounced the measure for providing an “alibi for avoiding congressional responsibility.” Gruening attributed the North Vietnamese attack to US escalation of the conflict, and contended, in any case, that the “allegation that we are supporting freedom in South Vietnam has a hollow sound.” Fulbright prevented any additional negative votes by privately assuring skeptical liberals that the president would never use the authority conferred by the resolution but would benefit politically from its adoption.Footnote 23

Despite the unanimous House vote and an 88–2 tally in the Senate, Johnson was displeased he received any criticism at all. Shortly after the vote, he denounced Gruening as “no good” and someone who failed to appreciate all the things he had done for Alaska, termed Morse “just undependable and erratic as he can be,” and blasted the “shitass” Ed Foreman.Footnote 24

Thanks in part to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, Vietnam played only a minor role in the fall campaign. But as the US military presence in Southeast Asia increased in early 1965, a handful of Senate liberals joined Morse and Gruening in criticizing US policy. One of this number, Stephen Young (D-Ohio), was an accidental winner in both 1958 and 1964, and carried little weight in the Senate. But younger liberals, such as George McGovern (D-South Dakota) and Frank Church, had more influence; the two World War II veterans urged a greater emphasis on diplomacy and criticized the initiation of a bombing campaign against enemy-controlled areas. It was no secret, columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak reported, that Democratic attacks on the president’s Vietnam policies were “both galling and embarrassing him” – to such an extent, the duo reported, the president purportedly told Church, “Frank, the next time you need a dam out in Idaho, go see Walter Lippmann about it.”Footnote 25

Through the spring of 1965, Johnson considered introducing another Gulf of Tonkin–like resolution, but rejected the move lest it trigger an intraparty debate in the Senate. With this option foreclosed, the president chose another route – transforming a vote on funding the troops into a de facto endorsement of his policy. As both he and his critics recognized, such a proposal would be almost impossible for members of Congress to oppose. On May 4, the president requested a $700 million supplemental appropriation for military operations in Vietnam, to communicate “that the Congress and the President stand united before the world in joint determination that the independence of South Vietnam shall be preserved and the Communist attack will not succeed.” The House passed the measure 408 to 7, with both parties’ leadership deeming the vote an endorsement of Johnson’s Vietnam policy.Footnote 26 Morse and Gruening, joined by Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson, cast the only negative votes in the Senate. Armed with this second endorsement of his handling of Southeast Asian events, Johnson approved a June 1965 request to more than double the US military presence in the region.

Lacking any chance of blocking Johnson through funding reductions or legislation, Senate skeptics of the war increasingly turned toward oversight. As Church privately told Morse in June 1965, it was “absolutely vital for the Senate to continue to discuss the alternatives to a widening war in Southeast Asia.” Fulbright soon agreed: admitting that he had not acted promptly enough because he did not “realize the seriousness of the situation until recently,” he sought to shape US public opinion through public hearings, which ran from January 28 through February 18, 1966. Witnesses included leading figures in the development of Cold War foreign policy, with Dean Rusk and General Maxwell Taylor defending administration policy and George Kennan and General James Gavin questioning it. The flailing administration response – Johnson pressed CBS not to televise the hearings, Taylor smeared Morse by saying his antiwar remarks would be good news to Hanoi – only heightened the hearings’ impact.Footnote 27

Fulbright’s leading biographer, Randall Bennett Woods, has acknowledged that while the hearings appear in retrospect to be a turning point in how Congress responded to the war, at the time only 37 percent of respondents knew of them. Nonetheless, they set the stage for more aggressive future Senate oversight. What Newsweek called their “superb drama” – especially sharp questions from committee members Fulbright, Morse, Gore, and Church, coupled with the difficulty of pro-administration witnesses in responding to them – made it easier for both ordinary Americans and the media to question the tenets of the administration’s policies. Because the Senate’s most influential prowar voices did not serve on the committee, the hearings presented a more one-sided view of Senate opinion than actually existed. Johnson certainly noticed: the president opened one White House dinner for senators by remarking, “I am delighted to be here tonight with so many of my very old friends as well as some members of the Foreign Relations Committee.”Footnote 28

Senate critics of the war nonetheless struggled to sustain momentum throughout 1966 – Fulbright, for one, recognized the “new role for me, and not a very easy one under our system.” That Morse and Gruening continued to press colleagues to enter what Church ridiculed as their “‘never-never-land’ of radically ineffectual dissent” made it difficult for the antiwar bloc to develop a consistent legislative strategy. Fulbright, Church, and McGovern preferred a more calculated approach, Morse and Gruening a more confrontational one, and in the end, the two sides could not agree. The year’s major Senate votes on Vietnam – a Gruening amendment allowing draftees to decline to serve in Vietnam and a Morse amendment to rescind the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution – attracted only five votes apiece, effectively providing, as Fulbright lamented, “a reaffirmation of the President’s power.”Footnote 29

At a minimum, the overwhelming defeats of the Morse and Gruening offerings seemed to prove the wisdom of antiwar senators relying on oversight to influence Johnson. But a vision of congressional power based primarily on oversight rather than legislation could work in both ways. With the Foreign Relations Committee becoming the center of antiwar sentiments in Congress, the Senate Armed Services Committee used similar tactics to champion a more aggressive US position in Southeast Asia. Though chaired by longtime Johnson confidant Richard Russell, the committee’s major figure on Vietnam matters was its second-ranking Democrat, John Stennis (D-Mississippi). Stennis also chaired the Preparedness Investigation Subcommittee (PIS), the Armed Services body responsible for conducting oversight investigations. Hearings in January 1966 – which Stennis hailed as “historic” – featured an array of prowar Democrats denouncing the administration for not sufficiently “fighting to destroy the enemy.”Footnote 30

The next year, PIS hearings explored what Stennis termed “the overall policy and public philosophy governing and controlling the conduct of the entire war.” Defense Secretary Robert McNamara was the sole civilian witness; military testimony deflected blame to civilian policymakers. Stennis denounced a bombing pause as “a tragic and perhaps fatal mistake”; his colleague, Henry Jackson (D-Washington), urged an expanded bombing campaign. The hearings had a dramatic policy effect. Johnson became keener to approve strikes against previously denied air targets in their aftermath.Footnote 31

The only Democrat to serve on both the Foreign Relations and Armed Services Committees was Stuart Symington (D-Missouri). Secretary of the Air Force before winning election to the Senate in 1952, Symington earned the nickname “Senator from the Air Force” both for his consistently pro–air force approach and his efforts to funnel government contracts to Missouri-based McDonnell Douglas. (One administration staffer observed that Symington was “obviously more interested in plugging for the air force than for the Administration generally.”)Footnote 32 This worldview initially made him strongly supportive of the military campaign in Vietnam. But Symington grew increasingly skeptical about the war as the 1960s progressed. As a participant in the Fulbright Hearings, he suggested that “without question we must take another look” at the basic policy if conditions in South Vietnam did not improve. A balanced-budget Democrat, the Missouri senator worried about the long-term economic effects of the war. Most importantly, he concluded that the administration’s secrecy was frustrating the ability of Congress to perform its oversight tasks.Footnote 33

Symington’s evolution into an antiwar senator began elsewhere in Southeast Asia. While he initially did not challenge the commitment in Vietnam, he opposed an expanded war as too costly and too likely to raise constitutional concerns. The tough questions Symington posed for William Bundy, who represented the administration, was the most notable development from late 1966 Foreign Relations Committee hearings on the US military presence in Thailand. The Missouri senator in particular focused on transparency issues, wondering whether “we are being so secretive about such an obvious operation” due to possible parallels between the mid-1960s situation in Thailand and mid-1950s conditions in Vietnam. Symington dismissed as “ridiculous” Bundy’s claim that “sophisticated” citizens could obtain sufficient information about Thai affairs in the New York Times. All of a sudden, this formerly predictable senator had become a wild card in the upper chamber’s debates about Southeast Asia, giving critics of the war in Vietnam credibility on military and national security matters they previously had lacked.Footnote 34

Despite their growing numbers, during the mid-1960s, an oversight strategy provided significant limits on what antiwar Democrats could accomplish. Their strength remained, as Fulbright admitted, in educating the public, not in exercising formal legislative powers. In the end, this strategy did little to prevent the dramatic expansion of US involvement in the war between 1964 and 1968.

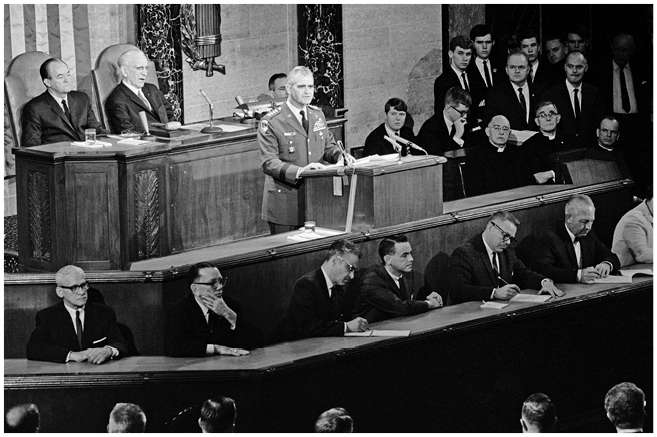

Figure 3.1 General William Westmoreland, commander of US troops in Vietnam, speaks to the United States Congress (April 28, 1967).

The Power of the Purse and the Limits of Congressional Power

The 1966, 1968, and 1970 elections changed the composition of Congress in subtle but ultimately significant ways. The 1966 midterms brought to the Senate three Republicans – Mark Hatfield (Oregon), Charles Percy (Illinois), and Edward Brooke (Massachusetts) – who to varying degrees questioned the wisdom of how Johnson had handled Vietnam. Their arrival coincided with more veteran Republicans criticizing the war effort more aggressively. The most noteworthy, Clifford Case (R-New Jersey), in 1967 denounced Johnson’s “misuse,” “perversion,” and “complete distortion” of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. The comments drew sharp criticism from conservatives in both parties; Stennis accused Case of unintentionally giving “comfort, encouragement, and hope to the enemy.”Footnote 35 But the development was critical – antiwar Democrats could hope to command a Senate majority only if they obtained some Republican support. In 1966, that seemed unlikely; by 1968, such an outcome seemed more promising.

Elections also altered the Vietnam-related composition of the Senate Democratic caucus, making it more open to working with more moderate Republicans. In 1968, several prominent critics of the war – Church, McGovern, Nelson, Gruening, Morse, and Joseph Clark (D-Pennsylvania) – were standing for reelection in what now would be described as red or purple states.

The group employed differing strategies regarding how to reconcile their positions on the war with the political realities of the states they represented. Church, McGovern, Clark, and Nelson sought to moderate their positions, to appease moderate or conservative voters at home. For instance, all four endorsed a public letter (coordinated by Church) opposing unilateral withdrawal from Vietnam. Fulbright, who faced only token opposition, signed on to give cover to Church, who was running in strongly Republican Idaho. McGovern, elected to the Senate by only 597 votes in 1962, aimed to neutralize resolutions condemning him passed by the South Dakota Veterans of Foreign Wars and the American Legion. The South Dakota senator privately told Gruening that he had not stood “100% on all your efforts because of the extremely conservative nature of my state and my forthcoming campaign, but my heart is always with you even when I have not been able to vote with you.”Footnote 36 The approach worked: not only were Church and McGovern reelected, but they increased their margins from 1962, even as GOP presidential nominee Richard Nixon easily carried their state.

Gruening and Morse, by contrast, did not in any way retreat. Gruening, if anything, grew more extreme. Beyond advocating unilateral withdrawal from Vietnam, he started opposing all defense appropriations, contending that Congress needed to be more confrontational in seeking to bring the troops home. Along with his advanced age (81), this voting pattern, representing a state heavily reliant on defense spending, heightened Gruening’s vulnerability. Two strong Republicans declared for the seat but, in the end, the incumbent failed to make it out of the primary, falling to Mike Gravel, a 38-year-old former state legislator.

His position on Vietnam likewise eroded Morse’s political standing. Morse had crossed party lines in 1966 to endorse Mark Hatfield against his prowar Democratic opponent, Representative Robert Duncan. Duncan then turned around to challenge Morse in the 1968 primary. With covert support from the Johnson administration, he held Morse to 49 percent of the vote. (A third candidate siphoned 5 percent of the vote and probably cost Duncan the victory.) A weakened Morse then narrowly lost the general election to Republican Bob Packwood.Footnote 37

Two years later, the Nixon administration’s number-one Senate target was another Democrat weakened by his early opposition to the war, Albert Gore. The Tennessee senator was ideologically out of step with his state – he managed only 51 percent in the 1970 Democratic primary – but also had antagonized both Nixon and Vice President Spiro Agnew. (In late 1969, Agnew said that Gore needed “to be removed to some sinecure when he can simply affect those within the sound of his voice and not the whole State of Tennessee”; in 1970, he ridiculed Gore’s “mistaken belief that Tennessee is located somewhere between New York City and Hartford, Connecticut.”) Gore’s opponent, Bill Brock, linked him with such liberal critics of the war as Fulbright, McGovern, and Ted Kennedy (D-Massachusetts). Near the end of the campaign, Gore admitted that his antiwar stance had gone “against the grain of the prevailing sentiment in Tennessee. Show Tennesseans a war and they’ll fight it.” Despite campaigning gamely, Gore lost by around four points.Footnote 38

The political reporter Don Oberdorfer regarded Gore as the Senate’s “most compelling leader against the Administration” on the war.Footnote 39 In his final years in the Senate, the Tennessee senator became more aggressive in his criticism – joining the likes of Morse, Gruening, and Stephen Young. The unsuccessful reelection bids of Gruening, Morse, and Gore, coupled with Young’s retirement, meant that, by 1971, relatively little difference existed between the tactics or belief systems of antiwar Senate Democrats and Republicans, mostly eroding the partisan distinction that had existed over the war during most of the Johnson administration.

After 1970, then, a more cohesive and bipartisan Senate antiwar bloc formed. These senators largely abandoned the Johnson-era tactic of focusing on oversight and instead aimed to use the appropriations power – by targeting military spending itself rather than, as in the early 1960s, the foreign aid program. And they increasingly found at least some support in the House of Representatives, which during the oversight era had tended to go along with Johnson’s Vietnam policies.

Richard Nixon’s promise to honorably end the war in Vietnam largely immobilized congressional action in 1969. But the president’s failure to promptly deliver on his promise generated what was then the most serious congressional effort to end the war. An amendment cosponsored by George McGovern and Mark Hatfield sought to cut off appropriations for all military operations in Vietnam except those related to the pullout of US troops, with a full withdrawal required by June 30, 1971.

Discussion of the amendment consumed the summer of 1970, its fate sealed when two moderate Republicans, George Aiken (R-Vermont) and John Sherman Cooper (R-Kentucky), came out against it, arguing that it could undercut the troops in the field. In his final speech on the measure, McGovern described “every senator in this chamber” as “partly responsible for sending 50,000 young Americans to an early grave, this chamber reeks of blood.”Footnote 40 That sort of rhetoric – when offered by Morse or Gruening in the mid-1960s – alienated colleagues and isolated the speaker. By 1970, however, the center of opinion in the upper chamber had shifted, and though McGovern–Hatfield went down to defeat, its 55–39 margin was respectable.

By this point Senate critics had shown they could obtain majority support for using the appropriations power to shape debate, at least when the focus was not Vietnam itself. On April 30, 1970, without congressional authorization, Nixon sent US combat troops to neutral Cambodia, seeking to disrupt North Vietnamese supply lines and fortify the South Vietnamese military position. The move, which Fulbright deemed “the most serious constitutional crisis we’ve ever faced” apart from the civil war, generated fierce criticism in the Senate. Within weeks, fifty senators had publicly criticized the administration’s actions, with fewer than a quarter of the body coming out in support. With Majority Leader Mansfield terming the Senate as the “only hope” of Americans who wanted to restore constitutional order, Church and John Sherman Cooper introduced an amendment to cut off funds for the operation.Footnote 41

In response, White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman searched for “inflammatory types to attack Senate doves – for knife in back disloyalty – lack of patriotism.” He found a few takers: Hiram Fong (R-Hawai’i) wildly claimed that “under the Cooper–Church theory, allied forces should never have invaded occupied France to get at the German Nazis in World War II.”Footnote 42 But the administration’s Senate allies mostly recognized that the amendment would pass when brought to a vote, and so concentrated on stalling, introducing amendments designed to delay progress of the measure.

Bob Dole (R-Kansas) futilely proposed giving Nixon authority to override any restrictions imposed by Cooper–Church if he considered doing so necessary for the national interest. An unsuccessful Robert Byrd (D-West Virginia) amendment sought to apply Cooper–Church only to actions the president did not consider necessary to protect US troops in South Vietnam. (One Cooper aide denounced Byrd as a “king’s man” who believed “that the President should not be restrained by legislative action in matters of foreign affairs and national security” – an accurate appraisal at the time, but ironic in light of Byrd’s jealous defenses of legislative prerogatives late in his career.)Footnote 43 A proposal from Robert Griffin (R-Michigan) sought to authorize US arrangements with third parties, such as Thailand, to serve as mercenaries in Cambodia. Each of these offerings narrowly lost, consuming debate time on the Senate floor as the troops completed their action in Cambodia. Pressed by Majority Leader Mansfield, Cooper and Church added a compromise provision deeming their amendment consistent with the president’s authority as commander-in-chief. That decision gave the amendment enough support to easily pass, 58–32 – though the House still rejected the offering.

The Cooper–Church outcome provided a reminder that any congressional effort to address the war based on funding restrictions rather than oversight hearings would require support from both chambers rather than only the Senate. That realization highlighted the importance of House efforts to grow opposition to the war. The first significant House antiwar amendment came in 1971, when Representatives Charles Whalen (R-Ohio) and Lucien Nedzi (D-Michigan) offered an amendment to cut off funding. The amendment failed, 158–254. For the first time, however, a majority of House Democrats (135–106) supported an end-the-war amendment. Nedzi’s role, moreover, provided a House counterpart to Symington – a prominent member of the Armed Services Committee who took a high-profile role against the war.

In the Senate, meanwhile, McGovern and Hatfield revived their efforts. Bob Dole ridiculed their backers as “a Who’s Who of has-beens, would-be’s, professional second-guessers, and apologists for the policies which led us into this tragic conflict in the first place.”Footnote 44 Seeking to broaden their support from 1970, the duo agreed to an amendment sponsored by freshman Lawton Chiles (D-Florida) to link a cutoff of the funds to the release of all American POWs. (National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger nonetheless complained about antiwar senators introducing “one amendment after another, forcing the Administration into unending rearguard actions.”) Four senators who had voted against McGovern–Hatfield in 1970 – Democrat Everett Jordan and Republicans Ted Stevens, Milton Young, and Charles Percy – backed the Chiles offering, which went down to defeat, 52–44 votes. This total was the highest number of votes for any antiwar measure until that time.Footnote 45

By 1971, then, the pattern was clear: each year, more and more senators were willing to vote to cut off funds for the war. The question was whether events or an appropriate legislative vehicle would emerge to bring the total to a majority. The time was right in late 1971. The release of the Pentagon Papers, a classified study of Vietnam escalation during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, raised doubts about the justification for the war. Mansfield used the opening to introduce an amendment declaring a pullout within nine months to be national policy – a more moderate offering than either the McGovern–Hatfield or Chiles amendments, since it did not explicitly authorize a date to withdraw funds for the war. The Mansfield amendment easily passed, 61–38, consolidating support from even conservative Democrats and attracting support from four Republican opponents of the McGovern–Hatfield amendment.

Given such results, Symington privately speculated that 1972 “could be the ‘year of decision,’” in which the Senate firmly established its power to shape Vietnam policy. A few months later, the Times’ John Finney correctly noted that “much of the energy and organization had gone out of the antiwar effort in the Senate.” The key reason was the surprising success of George McGovern’s bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, which unintentionally revived the more explicitly partisan lens through which the Senate had approached Vietnam policy in the mid-1960s. The prominent role that his antiwar legacy played in McGovern’s campaign complicated efforts to woo Republican backers for antiwar measures. Even in this environment, however, the Senate for the first time approved an amendment (cosponsored by Church and Cooper) to cut off funds for the conflict, although the overall military aid bill to which the amendment was attached then went down to defeat. Absent the withdrawal secured by the Paris Peace Conference, it seems likely Congress would have dramatically curtailed or terminated altogether funding for the war in 1973, especially given results of Senate elections in Iowa, Colorado, South Dakota, Delaware, and Maine, each of which replaced a prowar Republican with an antiwar Democrat.Footnote 46

Conclusion

In 1973, the new Congress did address one legacy issue from Vietnam – an effort to restrain the war powers of the executive. But advocates were, metaphorically, fighting the last war. Looking for a mechanism to prevent another president from abusing measures like the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution or the 1965 appropriations bill, the act required notification of Congress within forty-eight hours of sending troops into harm’s way and required the troops’ withdrawal after ninety days, absent a congressional authorization to use force. Some liberals criticized the latter provision as effectively granting a president some authority to send troops abroad without congressional authorization; some conservatives viewed the law as an infringement on the president’s power as commander-in-chief. The measure easily cleared the House, and a cross-ideological coalition put together by its chief sponsors – Stennis, Jacob Javits (R-New York), and Tom Eagleton (D-Missouri) – ensured necessary support in the Senate. Both chambers then narrowly overrode Richard Nixon’s veto. Whether the War Powers Act had any more actual power than a sense of Congress resolution, however, remains very much open to debate; it is unclear whether the act even would have posed a significant obstacle to Johnson’s militarization of the war in 1964 and 1965.

Leverage provided one critical element in the story of how Congress responded to the Vietnam War – between 1964 and 1973, the executive had the leverage, forcing Congress to react to external developments (Tonkin Gulf) or face accusations of undermining the troops in the field (the 1965 defense appropriations bill, McGovern–Hatfield). The final element of congressional involvement in the war, however, featured Congress with leverage, as the new administration of Gerald Ford unsuccessfully sought to procure emergency aid to forestall the collapse of South Vietnam in 1975. After abandoning plans for a massive infusion of military aid to Saigon, the administration called for humanitarian assistance for the South Vietnamese, as well as congressional authority to evacuate remaining US nationals.

The proposal cleared the House after a tumultuous debate in which newly empowered Watergate Democrats, deeply suspicious of any grant of executive power, worried about another Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. (Michael Blouin, a moderate Democrat elected in 1974 from an eastern Iowa district, reflected on the day: “If people think panic reigns in Saigon, they should have checked the tempo of this floor.”)Footnote 47 The House vote proved irrelevant. In the Senate, freshman Foreign Relations Committee member Dick Clark (D-Iowa) championed what he deemed a compromise, under which the aid would be released only when Ford committed to respecting the congressional power to declare war in any evacuation plan. Discussions were still ongoing over the proposal when the South Vietnamese regime collapsed.

The chaos associated with the final, failed aid package provided a reminder of the reactive nature of how Congress responded to Vietnam once funding for the war shifted from the foreign aid program – which allowed for more effective oversight – to the defense budget. While individual legislators, such as Symington, were able to exercise significant influence during the late 1960s and early 1970s, and congressional activism played some role in challenging the expansion of the war during the Nixon years, the legislature struggled to wield its power as Johnson made the key decisions to expand the war in the mid-1960s.