Introduction

The brown hairy dwarf porcupine Coendou vestitus is one of the rarest of the seven species of porcupines (genus Coendou) that occur in Colombia (Ramírez-Chaves et al., Reference Ramírez-Chaves, Suárez-Castro, Morales-Martínez and Vallejo-Pareja2016). It is a small species (head–body length 330–370 mm), characterized by having three types of fur: long dorsal fur, bicolored defensive fur, and bristles (Voss, Reference Voss, Patton, Pardiñas and D'Elía2015). Since its description more than a century ago (Thomas, Reference Thomas1899), it has been recorded from only six localities. This species is considered endemic to both sides of the Eastern Cordillera in the Colombian Andes, which is a complex ecosystem with topographical and biological diversity and high levels of endemism (Olson & Dinerstein, Reference Olson and Dinerstein2002; Armenteras et al., Reference Armenteras, Gast and Villareal2003; Sánchez-Cuervo et al., Reference Sánchez-Cuervo, Aide, Clark and Etter2012). Andean ecosystems are a global conservation priority as only 25% of their original extent remains (Armenteras et al., Reference Armenteras, Gast and Villareal2003).

Although C. vestitus is considered rare (Ramírez-Chaves et al., Reference Ramírez-Chaves, Suárez-Castro, Morales-Martínez and Vallejo-Pareja2016), this condition has not been evaluated, and it has been suggested based only on the absence of data and the paucity of voucher specimens. Information on the ecology, genetics, natural history and conservation status of the species is also scarce, and in the case of the latter, contradictory. This porcupine is categorized as Data Deficient on the IUCN Red List (Weksler et al., Reference Weksler, Anderson and Gómez-Laverde2016), with the assessment considering the presence of the species from only two localities, although in the same assessment three localities were mentioned. Nationally, the species has been categorized as Vulnerable based on its reduced geographical range as a result of habitat loss and fragmentation (Amori & Gippoliti, Reference Amori and Gippoliti2003; Alberico & Moreno, Reference Alberico, Moreno, Rodríguez-Mahecha, Alberico, Trujillo and Jorgenson2006; MADS, 2017). Currently, it is the only porcupine species categorized as threatened in Colombia (Alberico & Moreno, Reference Alberico, Moreno, Rodríguez-Mahecha, Alberico, Trujillo and Jorgenson2006). Here, based on available literature, specimens in natural history museums and collections, and data from recent records, we evaluate the level of rarity of the species and reassess its conservation status.

Methods

Assessing rarity

To evaluate the rarity of the species we followed the criteria of Yu & Dobson (Reference Yu and Dobson2000), based on four characteristics: (1) local population density, (2) range, (3) the number of habitat types in which the species occurs and (4) body size. In addition, we suggest factors that may have determined the rarity category of this species. As the species population density has not been assessed, we documented the number of records per year since the species description. We consider the population density to be low if the number of records evaluated is < 1 for each 10-year interval (there are c. 10,000 records of mammals in databases for Cundinamarca, the department in which C. vestitus has been historically recorded). We also estimated the species range and related this to the rarity level using the extent of occurrence (EOO) and area of occupancy (AOO). We calculated the EOO using the minimum convex polygon (linking the known points of occurrence for the species), and the AOO by summing the area of grid squares in which the species is known (using grid squares of 2 km2 as recommended in IUCN, 2010) in GeoCAT (Bachman et al., Reference Bachman, Moat, Hill, de la Torre and Scott2011). For this we used data from six confirmed localities. Three of these are voucher specimens housed at Colombian collections and the other three are photographic records (Table 1). The photographs showed characters used to differentiate C. vestitus from other species in this genus: dorsal pelage with long blackish fur that partially or completely conceals defensive quills, and bicoloured bristle-quills (Voss & da Silva, Reference Voss and da Silva2001; Voss, Reference Voss, Patton, Pardiñas and D'Elía2015; Plate 1). We excluded the record ICN 3505 from our analyses because the specimen was transported from another locality in the western part of the Eastern Cordillera; the location on the label of the specimen is in a market area (Alberico & Moreno, Reference Alberico, Moreno, Rodríguez-Mahecha, Alberico, Trujillo and Jorgenson2006).

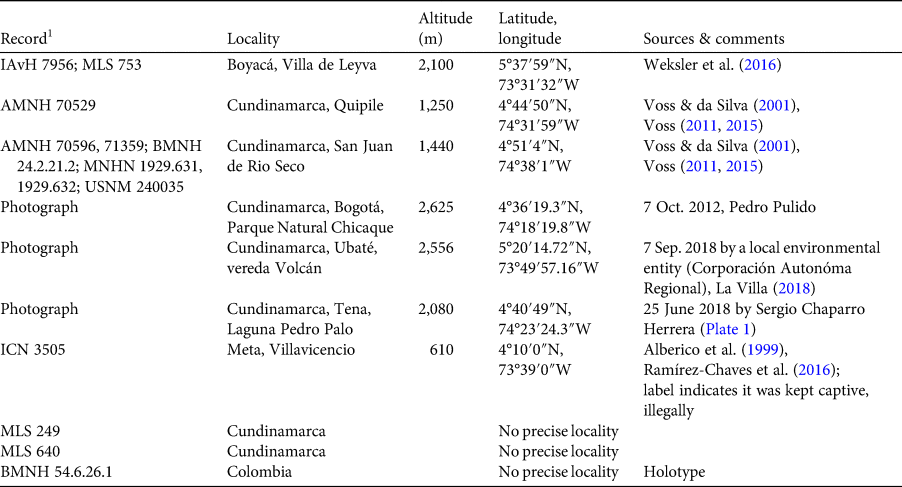

Table 1 Records of Coendou vestitus in Colombia. Records from six confirmed localities were used in the analyses; one record (ICN 3505) was excluded.

1IAvH, Instituto de Investigaciones Biológicas Alexander von Humboldt; MLS, Museo de La Salle; AMNH, American Museum of Natural History; BMNH, British Museum of Natural History; MNHN, Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle; USNM, National Museum of Natural History; ICN, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Plate 1 Photographic record (June 2018) of Coendou vestitus from Pedro Palo, Tena, Colombia (Table 1). Photo: Sergio Chaparro.

We also considered the number of habitats occupied by the species. For this, we overlaid the EOO on the ecoregions of Colombia, following the classification of terrestrial ecoregions (Olson et al., Reference Olson, Dinerstein, Wikramanayake, Burgess, Powell and Underwood2001). We evaluated body size based on information from the labels of the reviewed voucher specimens and from the literature (Voss, Reference Voss, Patton, Pardiñas and D'Elía2015; Ramírez-Chaves et al., Reference Ramírez-Chaves, Suárez-Castro, Morales-Martínez and Vallejo-Pareja2016), and compared this trait with other species of Coendou.

Conservation status

To reassess the species conservation status, we used information on the level of rarity, EOO and AOO (IUCN, 2012). We included the level of rarity and the ecoregions the species inhabits to infer the conservation status of the species because of the absence of information on other factors that can influence the AOO, such as biotic interactions (predation, competition) and landscape (connectivity and shelter) (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Nascimento and Aguiar2013). We also examined whether the EOO or AOO of C. vestitus overlaps with protected areas, by using the protected areas layer for Colombia (October 2018; SINAP, 2018), and evaluated the per cent of forest area that remained unchanged during 2016–2017 within the polygon of the species range (IDEAM, 2018). To evaluate overlap of the AOO and EOO with protected areas, we estimated the extent (km2) of protected areas inside the EOO polygon using as a limit the elevational range of the species, and determined the number of confirmed localities inside protected areas.

Results

Rarity

Our findings indicate that C. vestitus matches the criteria of an extremely rare species (Category H; Yu & Dobson, Reference Yu and Dobson2000), based on all four factors evaluated.

Population density

From the description of C. vestitus to the present, we found only 12 voucher specimens and photographs of three living specimens. Three records had no precise locality information. The records date from the species description in 1889 to photographic records from Cundinamarca in 2018 (Plate 1, Table 1). The scarcity of records suggests a low population density, considering that several biological expeditions have visited the area in which the species occurs (Cundinamarca is the Department in which Bogotá, the capital of Colombia and home of the main Colombian academic institutions, is located).

Range

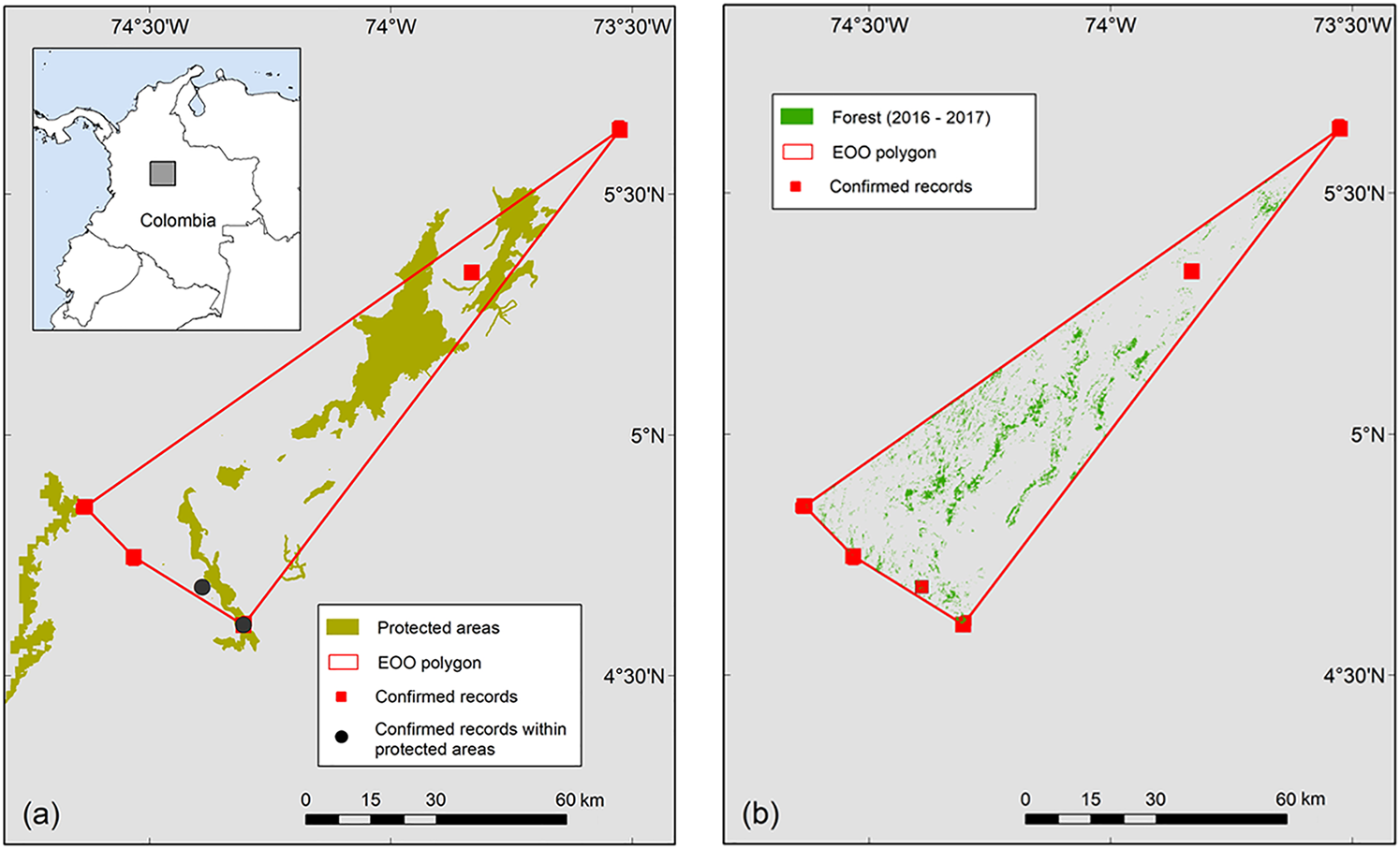

It has been suggested that the elevational range of C. vestitus is 1,300–2,600 m (Barthelmess, Reference Barthelmess, Wilson, Lacher and Mittermeier2016), 250–2,000 m (Alberico et al., Reference Alberico, Rojas-Díaz and Moreno1999) and 600–1,440 m (Ramírez-Chaves et al., Reference Ramírez-Chaves, Suárez-Castro, Morales-Martínez and Vallejo-Pareja2016). However, based on the information from confirmed localities, and discarding a dubious record from Villavicencio, the elevational range appears to be from 1,250 m (Cundinamarca, Quipile) to 2,600 m (Cundinamarca, Chicaque). The estimated area of the species range is based on only six confirmed localities (Table 1, Fig. 1), with an estimated EOO of 3,323 km2 and an AOO of 24 km2.

Fig. 1 Extent of occurrence (EOO) of Coendou vestitus, with (a) protected areas within the EOO, indicating the two records in protected areas, and (b) forest coverage in 2016–2017.

Number of habitat types in which the species occurs

Overlaying the EOO on the terrestrial ecoregions map indicated that the species only occurs in tropical moist broadleaf forest (Olson et al., Reference Olson, Dinerstein, Wikramanayake, Burgess, Powell and Underwood2001). This ecoregion corresponds to the highly threatened sub-Andean and Andean forests.

Body size

The adult body size of C. vestitus (total length of head and body 330–370 mm) is within the range observed for small Coendou species (C. insidiosus 310–350 mm; C. nycthemera 290–380 mm; C. pruinosus 320–380 mm; C. rufescens 340–410 mm; C. melanurus 330–435 mm; C. quichua 330–440 mm; C. speratus 330–440 mm; C. spinosus 285–470 mm; C. bicolor 450–500 mm; C. prehensilis 400–530 mm), being the third smallest species of the genus after C. ichillus (260–290 mm) and C. roosmalenorum (290 mm). Coendou vestitus has, however, a considerably shorter tail than the latter species.

Conservation status

We found only two localities (of the six confirmed) within conservation areas (33.3% of the occurrences), although the EOO polygon intersected with 35 protected areas, managed by two institutions (Corporación Autónoma Regional and Parques Naturales Nacionales de Colombia). Specifically, these 35 areas include one Soil Conservation District, five Regional Protected Forest Reserves, eight Regional Integrated Management Districts, and 21 Natural Civil Society Reserves (UNEP–WCMC, 2019). The portions of the protected areas within the EOO polygon have a total area of 1,025 km2, with 1,298 km2 of the EOO not lying within protected areas (Fig. 1a). When overlapping the forest coverage with the EOO polygon, the forest coverage during 2016–2017 was 219 km2 (6.6%). Considering the species' range and its rarity, we recommend that C. vestitus is recategorized from Data Deficient to Endangered based on the following criteria: (1) B1b(iii,iv,v) and B2b(iii,iv,v): with an EOO of < 5,000 km2 (B1) and continuing decline inferred (b) in extent and/or quality of habitat (iii), number of locations or subpopulations (iv) and the number of mature individuals (v), and similarly with an AOO < 500 km2 (B2); (2) C2b: population size estimated to number < 2,500 mature individuals with a continuing decline, observed, projected, or inferred (C), and, continuing decline, observed, projected or inferred, in numbers of mature individuals, and extreme fluctuations in number of mature individuals (2b).

Discussion

Our recommendation to categorize C. vestitus as Endangered follows IUCN (2012) recommendations to assess poorly known taxa based on information on inferred habitat loss and restricted distribution, to avoid assigning a Data Deficient category. The current IUCN information (Weksler et al., Reference Weksler, Anderson and Gómez-Laverde2016) is incomplete (with AOO and EOO unknown) because it includes data for only from two localities (Voss, Reference Voss, Patton, Pardiñas and D'Elía2015). The periodic re-evaluation of a species’ Red List status is an important tool for the planning, monitoring and management of biodiversity conservation (Hoffmann et al., Reference Hoffmann, Hilton-Taylor, Angulo, Böhm, Brooks and Butchart2010; Angulo et al., Reference Angulo, von May and Icochea2019).

Besides being an endemic and rare species, our findings confirm that C. vestitus is restricted to an ecosystem in which habitat is being lost and there are continuing threats from anthropogenic transformation (Thiollay, Reference Thiollay1996; Armenteras et al., Reference Armenteras, Gast and Villareal2003; Angulo et al., Reference Angulo, von May and Icochea2019). The Eastern Cordillera comprises 40% of Andean ecosystems, but only 27% of its original vegetation cover remains. Although this region is characterized by high species richness and endemism it is one of the least known and least protected ecosystems (Armenteras et al., Reference Armenteras, Gast and Villareal2003; Rodríguez-Erazo et al., Reference Rodríguez-Eraso, Pabón-Caicedo, Bernal-Suárez and Martínez-Collantes2010). Habitat loss affects the persistence of small mammals, which play important ecological roles, for example as seed dispersers of pioneer species, and in trophic and predator–prey relationships (Decher, Reference Decher1997; Brose et al., Reference Brose, Jonsson, Berlow, Warren, Banasek-Richter, Bersier and Blanchard2006; Lima et al., Reference Lima, Oliveira and Chiarello2010; Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Hsieh and Nakazawa2016).

Although C. vestitus has previously been considered a rare species because of the scarcity of records (Ramírez-Chaves et al., Reference Ramírez-Chaves, Suárez-Castro, Morales-Martínez and Vallejo-Pareja2016), there are other reasons for it to be considered rare (Cofré & Marquet, Reference Cofré and Marquet1999). Although other porcupines in Colombia are known from fewer specimens (e.g. C. ichillus), they are not endemic to the country, having a wider distribution (Voss, Reference Voss, Patton, Pardiñas and D'Elía2015). Our confirmation of rarity is based on a combination of apparent low local population density, a small range, occurrence in only one habitat type, and small body size.

In general, small-sized species of Coendou (e.g. C. ichillus, C. roosmalenorum and C. vestitus) have more restricted distributions in the northern part of South America compared to the larger species that have only one type of quills in adulthood (e.g. C. prehensilis and C. bicolor; Voss, Reference Voss, Patton, Pardiñas and D'Elía2015). The rarity of C. vestitus is perhaps associated with homoplastic functional traits such as the presence of three types of hairs in adulthood (i.e. with less protection against predators than species with a body fully-covered by quills) (Voss et al., Reference Voss, Hubbard and Jansa2013) and small body size (Gaston & Blackburn, Reference Gaston and Blackburn1995; Yu & Dobson, Reference Yu and Dobson2000). Several species of African small mammals have been categorized as rare or Vulnerable (Schlitter, Reference Schlitter and Lidicker1989; Decher, Reference Decher1997) because their size could influence predator–prey relationships (Brose et al., Reference Brose, Jonsson, Berlow, Warren, Banasek-Richter, Bersier and Blanchard2006; Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Hsieh and Nakazawa2016). In this context, additional morphological characters may confer an adaptive advantage to large Coendou species: a body mostly covered by quills in adulthood provides a possible advantage against predators (Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Juanes and Rountree2000; Speed & Ruxton, Reference Speed and Ruxton2005), the swollen nasofrontal sinuses protect the brain, and a larger tail facilitates arboreal locomotion, as observed in C. bicolor and C. prehensilis (Voss et al., Reference Voss, Hubbard and Jansa2013; Voss, Reference Voss, Patton, Pardiñas and D'Elía2015). The morphological and/or evolutionary reasons for the restricted range of small-sized Coendou are, however, as yet unclear, and require further research.

Although 106 genera, 333 species and 61 subspecies of rodents are considered threatened and have high endemism (Ceballos & Brown, Reference Ceballos and Brown1995; Amori & Gippoliti, Reference Amori and Gippoliti2001, Reference Amori and Gippoliti2003, IUCN, 2020) a relatively lower per cent of rodents are categorized as threatened compared to other mammalian groups (Ceballos & Brown, Reference Ceballos and Brown1995; IUCN, 1997; Amori & Gippoliti, Reference Amori and Gippoliti2001). No Coendou species are as yet categorized as threatened (IUCN, 2017): six are categorized as Data Deficient, including C. vestitus, and eight as Least Concern.

The only locations of C. vestitus within protected areas are in the 2.44 km2 Nature Reserve Parque Natural Chicaque and the 0.45 km2 Natural Civil Society Reserve Tenasuca de Pedro Palo, which together correspond to only 0.08% of the species’ range (Fig. 1a). In addition to the small EOO, the area of the 35 protected areas within the EOO is small (a mean of 29 km2 per protected area). The area surrounding the EOO is severely affected by extensive commercial plantations and urban settlements, with only c. 50% of the ecoregion unaffected (Armenteras et al., Reference Armenteras, Gast and Villareal2003; Sánchez-Cuervo et al., Reference Sánchez-Cuervo, Aide, Clark and Etter2012; Angulo et al., Reference Angulo, von May and Icochea2019). This limits connectivity (Bright, Reference Bright1993), which is important for the persistence of a species (Passos et al., Reference Passos, Mello, Isati-Catalá, Mello, Bernardi and Varzinczak2016). Maintenance, extension or connection of protected areas, connecting the relict habitats, could help to protect C. vestitus (Cofré & Marquet, Reference Cofré and Marquet1999; Amori & Gippoliti, Reference Amori and Gippoliti2003; Armenteras et al., Reference Armenteras, Gast and Villareal2003).

Conservation strategies and financial resources need to be established for threatened and endemic species and for species with restricted distributions (Cofré & Marquet, Reference Cofré and Marquet1999; Isaac et al., Reference Isaac, Turvey, Collen, Waterman and Baillie2007). However, for mammals most monitoring and conservation efforts are directed at large or charismatic species. Less attention has been directed at rodents, even though the group has a high extinction rate (Amori & Gippoliti, Reference Amori and Gippoliti2001, Reference Amori and Gippoliti2003; Armenteras et al., Reference Armenteras, Gast and Villareal2003). Prioritizing the conservation of C. vestitus has the potential to contribute to the protection of the ecosystems in which it occurs and of co-occurring species. We recommend that national agencies prioritize this porcupine species, together with other species in urgent need of monitoring.

Porcupines remain a poorly known group, both at national and Neotropical levels (Voss, Reference Voss2011). Knowledge of the ecology of C. vestitus is mostly based on inference from other porcupine species (e.g. Alberico & Moreno, Reference Alberico, Moreno, Rodríguez-Mahecha, Alberico, Trujillo and Jorgenson2006; Weksler et al., Reference Weksler, Anderson and Gómez-Laverde2016). Our compilation of information on C. vestitus highlights the need for further fieldwork and data collection. Nevertheless, threats to porcupines are evident, in particular loss of habitat, illegal trade, road-kills, and hunting for consumption (de Freitas et al., Reference de Freitas, de França and Veríssimo2013; Racero-Casarrubia et al., Reference Racero-Casarrubia, Chacón-Pacheco, Humanez-López and Ramírez-Chaves2016). In Colombia, illegal captivity has also been documented (on a voucher specimen label; Table 1) as a threat to the species. Our compilation of data and our findings form the basis for further research and for the establishment of conservation strategies and future evaluations of the distribution and conservation status of C. vestitus.

Acknowledgements

We thank Hugo López (Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia) and Cristian Cruz Rodríguez (Museo de La Salle) for allowing us to review specimens under their care; Luiz H. Varzinczak for useful comments on the text; Pedro Pulido, Sergio Chaparro and Carlos Aya for sharing records and photographs; and Mario Ernesto Jijón Palma for help with the map. MMTM thanks Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brazil (Finance Code 001) for support. HERC thanks Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt (Andrés M. Cuervo and María López Rodríguez) for access to voucher specimens, and The Rufford Small Grants (Grants 23710-1 and 29491-2), the Universidad de Caldas (projects 0743919 and 0223418), and the Science and Scholarship Committee of the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, for support. FCP thanks the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (Grant 307303/2017-9).

Author contributions

Project design: MMT-M, HER-C; data collection: MMT-M, HER-C, EAN-U; evaluation of rarity and threatened status: MMT-M, FCP; writing: MMT-M, HER-C.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.