1. Introduction

According to research in higher education, international academic mobility has steadily increased in recent years and decades, with one study noting that ‘at the global level, 42.3% of academics experience or have experienced some kind of international mobility’.Footnote 1 For UK universities in particular, it is found that there has been a considerable rise in foreign academic staff: 27% of all academic staff in 2007 were foreign, which rose to 32% in 2018 (and for some fields it was up to 50%).Footnote 2 Indeed, it may be argued that this internationalisation is exactly what can be expected in academia. According to an expert on academic mobility, ‘higher education and science are international more or less by definition in adhering to the principle of borderless generation, dissemination and search of/for new systematic knowledge’.Footnote 3

Yet, in most countries and universities, ‘law’ is the exception to this trend as few legal scholars pursue their academic careers in a country that is different from their home jurisdiction.Footnote 4 Thus, in line with the view that ‘law seems to be a parochial, state-based subject’,Footnote 5 being legally trained in one jurisdiction but permanently working in another may be seen as akin to a change to another academic discipline. There are few counterexamples to this jurisdictional immobility of careers in legal academia. Some are about cases where legal scholars spend time abroad for an LLM or PhD degree and then return to their home jurisdictions.Footnote 6 There is also some flexibility within some common law jurisdictions (eg Australian legal scholars at universities in Singapore, UK legal scholars at universities in Hong Kong). However, the UK is the most interesting counterexample, as its universities have shown a great willingness to appoint legal scholars from any legal tradition and any part of the world, irrespective of their main legal education.Footnote 7

It is likely that a variety of reasons have contributed to this unique UK phenomenon. The general literature on mobility in higher education suggests that push and pull factors play a complex role, including: the increased attractiveness of the universities of the host country; the transferability of academic qualifications; a common language; geographic proximity, as well as individual biographical features.Footnote 8 Similarly, there are likely to be a variety of factors related to both legal academia in the UK and the foreign countries that account for the phenomenon of a large proportion of UK-based foreign-trained legal scholars. Focusing on the latter reasons,Footnote 9 the literature suggests that this process towards increasingly internationalised law faculties happened without any central planning, due to factors such as the role of the Commonwealth legal empire and European integration, a growing number of law students and the corresponding need for more academic staff, and the open and merits-based recruitment process of UK universities.Footnote 10

This phenomenon of foreign-trained legal scholars in the UK also raises questions of how their ‘foreignness’ impacts on their research and teaching and what further implications this impact may have. A ‘positive story’ may argue that foreign-trained legal scholars act as ‘change agents’Footnote 11 in their departments, for example, promoting comparative and international legal scholarship and teaching. In addition, the impact of foreign-trained legal scholars may go beyond universities, as they train future lawyers and may even contribute to the UK's legal culture becoming more European, civil-law oriented and international. However, there could also be a ‘negative story’; namely, that foreign-trained legal scholars do not ‘fit in’ because they and their UK-trained colleagues have profoundly different approaches to research and teaching. Specifically, for legal scholars from civil law countries, it may matter that – according to some – there is said to be a deep divide between the legal mentalities of the civil law and the common law,Footnote 12 with EU law-based civil law influence on the common law even being called a ‘legal irritant’.Footnote 13

The topic of foreign-trained legal scholars in the UK is thus complex but also underexplored in the current literature. This paper cannot address all aspects that could potentially be relevant. Rather it will focus on the following. First, it will present original data that shows the prevalence of foreign-trained legal scholars at Russell Group universities. Secondly, it will discuss the results of a survey of foreign-trained legal scholars. This survey aimed to explore how respondents deal with the challenge of being based at a university where there may be an expectation that they will assimilate with UK-trained legal scholars, in addition to considering the impact of the UK's departure from the European Union (Brexit). Finally, the conclusion relates the findings of this paper to the growing volume of general research on legal scholarship and legal scholars.

2. Prevalence of foreign-trained legal scholars at Russell Group universities

(a) Method and scope of data collection

Few data exist that show the extent of foreign-trained legal scholars in the UK. A paper by the former Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) reported that, in 2010–11, 21% of academic staff at law departments of UK universities had non-UK nationality.Footnote 14 Yet, further details are not provided and it is not clear how many of those were foreign-trained legal scholars. By contrast, a book by Anthea Roberts reports data on legal scholars who have a first law degree from other jurisdictions; yet, her research is specifically interested in a sample of ‘international law academics from elite universities’, finding that around 74% of such UK academics have a first law degree from another country.Footnote 15 Finally, an article by Mark Davies examined the educational background of legal academics according to samples of up to eight universities in four groups (Oxbridge, non-Oxbridge Russell Group, pre-1992 non-Russell Group, post-1992 sector) identifying 31%, 32%, 41% and 22% respectively of academics in these groups having a first degree from overseas, though not analysing these foreign-trained legal scholars in further detail.Footnote 16

For the purposes of this paper, the websites of the 23 Russell Group universities that offer an undergraduate law degreeFootnote 17 were scrutinised in order to identify the educational background of legal scholars. If a particular website did not provide clear information, this was supplemented by a search via Google and LinkedIn in order to identify scholars’ university degrees. Using this method, it was possible to ontain reliable information for 1469 of 1530 (ie about 96%) of the legal scholars of the Russell Group universities (for details see the next section). The collection of information beyond the Russell Group universities had been contemplated too. However, the websites of many of the less research-focussed universitiesFootnote 18 provide little information about their academic staff, and thus any information about their academic education would not be representative about these universities.Footnote 19 Specifically for EU academic staff, a general study of UK universities also found that Russell Group universities are the universities with high numbers of foreign staff.Footnote 20

The search included all legal scholars with the job titles of ‘lecturer’, ‘senior lecturer’, ‘reader’, ‘assistant professor’, ‘associate professor’ and ‘professor’, but excluded visiting and emeritus positions as well as any other title (eg teaching fellow, research fellow). Given the use of information available on university websites, it was not possible to identify whether individuals were on leave or in a part-time position.Footnote 21 As the identification of legal scholars used the websites of universities’ law departments (or, in the terminology of some universities, law faculties or law schools), the search did not identify legal scholars employed in other departments or, in the case of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, those who have a position at only one of the colleges.

Regarding the ‘foreignness’ analysed in this paper, the search aimed to identify anyone who did their initial law degree (LLB, JD or equivalent) in a country other than the UK – in the following these individuals are called ‘foreign-trained legal scholars’.Footnote 22 Thus, as far as UK legal education is concerned, it was not distinguished whether a scholar studied in England, Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland. As the focus was on persons with a foreign legal education, the data collection did not consider foreign academic qualifications in other fields (nor would it have been possible to identify someone's nationality). The decision to focus on the undergraduate legal education was taken since it usually covers all relevant areas of law of the jurisdiction in question, while postgraduate degrees can be highly specialised (or may focus on non-domestic laws). While it is possible that, despite a foreign undergraduate legal education, the subsequent educational and work experience leads to a process of assimilation, it would be difficult to identify general criteria that would capture such cases.

(b) Findings by countries and universities

The aforementioned search modus identified 539 foreign-trained legal scholars at Russell Group universities. Overall, this amounts to 36.69% of all of its academic staff in law. This section presents and discusses these findings, distinguishing between the origin countries of the foreign-trained legal scholars on the one hand and their current universities on the other.

The foreign-trained legal scholars at the Russell Group universities come from all parts of the world, though there are some gaps in Africa and the Middle East, Central Asia and Southeast Asia (see Figure 1). Distinguishing between continents, the majority of foreign-trained legal scholars are from other European countries (55.10%), followed by legal scholars from Asia (14.47%), Australia and Oceania (11.69%), North America (10.20%), Africa (4.64%) and South America (3.90%). Thus, in the present case, this international academic mobility is not only directed towards the UK as a country of the ‘Global North’,Footnote 23 but is also mainly the result of legal scholars from the Global North moving to the UK. Conversely, there are fewer legal scholars from the ‘Global South’ moving to the UK. This is likely to be the result of a variety of reasons: immigration rules, geographic distance and relocation costs, as well the costs of gaining a postgraduate academic qualification (LLM, PhD etc) in the UK, given that this often precedes a career in UK academia.

Figure 1. Map of origin countries of foreign-trained legal scholars (highlighted in black)

Aggregating the number of foreign-trained legal scholars for all countries with an Anglophone legal systemFootnote 24 shows that they represent 39.33% of all foreign-trained legal scholars in the UK. Specifically, as displayed in Table 1, Australia, Ireland, the US, Canada, India, New Zealand and South Africa are in the top 20 origin countries. Thus, this aspect of the data may be read as confirming the enduring role of the common law (and the Commonwealth) for academic mobility. In the case of legal scholars from the US, the uncertainty of early-career positions at US universities (be it as a visiting assistant professor or at a tenure-track position) could also be a ‘push factor’ in favour of UK universities.

Table 1. Top 20 origin countries by number of foreign-trained legal scholars

The remaining 60.77% of all foreign-trained legal scholars are from non-Anglophone countries. These are mainly Europeans, but Table 1 shows that there is also a fairly high number of legal scholars from China (similar to other academic fieldsFootnote 25). Aggregating the numbers for scholars from EU Member States shows that they represent 51.76% of all foreign-trained legal scholars. The intuitive explanation is that the UK's (now) former membership of the EU (including free movement, the ability to teach EU law,Footnote 26 etc) was one of the motivations for these scholars in deciding to pursue their academic careers in the UK. With regard to the specific EU countries ranked at the top of the list of origin countries, it is likely that for countries such as Greece and Italy the fact that their universities have not had many available positions in recent years (or even decades) may also have played a part.Footnote 27 For Germany in particular, it is likely to matter that most academic positions below the rank of a full professor are temporary assistant contracts, while in UK universities even the positions at the lowest rank (lecturer or assistant professor) can be of a permanent and independent nature.Footnote 28 Furthermore, the UK system of gradual promotions (eg, lecturer, senior lecturer, reader, professor) may play a role: thus, some foreign legal scholars may initially have intended to work in the UK for only a limited period but then decided to stay, having succeeded in one or more academic promotions.

The proportion of foreign-trained legal scholars in Russell Group universities ranges from 16.67% to 57.52%. It is not easy to find general explanations of why universities have higher or lower proportions of foreign-trained legal scholars. From the data shown in Table 2, it can be seen that the London universities and Oxbridge have fairly high numbers, while the lowest proportions are mainly at the universities in the periphery (though not the two Scottish universities).Footnote 29 It may also be thought that the size of the universities and their international ranking may be correlated with being able to attract and afford a large proportion of foreign-trained legal scholars. Yet, the correlation between the proportion of foreign-trained legal scholars and the total number of academic staff is fairly weak (0.34) and the universities at the top three and bottom three of Table 2 rank similarly in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings.Footnote 30

Table 2. Foreign-trained legal scholars at Russell Group universities

It could be the case, however, that the information about top origin countries, also displayed in Table 2, can provide more precise explanations for particular universities. For example, given its location, it is no surprise that Irish-trained legal scholars are the largest group at Queen's University Belfast. The large number of Chinese-trained legal scholars at Durham can be explained by the establishment of a Centre for Chinese Law and Policy,Footnote 31 and the large number of French-trained legal scholars at Exeter by a joint undergraduate programme in English and French law (‘double maîtrise’).Footnote 32 In other instances, established networks may play a role. For example, given the civilian elements of Scots law,Footnote 33 it is perhaps no surprise that Glasgow and Edinburgh have a large proportion of German and Italian legal scholars. Oxford has a high number of Australian trained legal scholars and in total 65.85% of its foreign-trained legal scholars are from Anglophone countries. This number is considerably higher than the average proportion of all of the universities (39.33%) and this may suggest that Oxford relies more on old common law networks than the more recent European ties.Footnote 34

3. Survey of foreign-trained legal scholars

(a) Design of survey and response rate

The information presented and discussed below was collected through a web-based survey, circulated on 27 November 2020 and reproduced in the Annex to this paper. In online surveys, it is often difficult to achieve a high response rate.Footnote 35 Thus, the survey was deliberately kept short with just four multiple-choice questions and one free-text question (asking respondents about any further comments they may have). In substance, the main aims were to explore how far the non-UK training of foreign-trained legal scholars might matter for their research and teaching, how far their ‘foreignness’ may have led to forms of discrimination and how their choice for UK universities may change as a result of the Brexit referendum.

The survey was sent to the 539 foreign-trained legal scholars of Russell Group universities; 244 of them responded to the survey. Thus, the response rate of the survey was 45.27%, which is a very good rate when compared with similar online surveys.Footnote 36 There were some variations between the response rates between EU and non-EU respondents on the one hand, and between Anglophone and non-Anglophone respondents on the other:Footnote 37 namely a slightly higher response rate of EU respondents (48.75% compared to 41.54% of the non-EU respondents) and a considerably higher response from non-Anglophone respondents (49.85% compared to 38.21% of Anglophone respondents).

These different response rates are already an interesting finding. They may partly be induced by the Brexit-related fourth question. Yet, it is more likely that some of the Anglophone respondents did not even open the survey as they felt that the ‘problem’ about having a foreign legal education may be less relevant for them. Indeed, one of the free-text responses stated ‘I am foreign-trained in one sense but Australian-trained is not foreign-trained in many respects’ (R18).Footnote 38 However, it is also interesting to refer to another quote which states that ‘being Irish in the UK is often a weird mid-place since while I consider myself a migrant, often English (as opposed to Scottish or Welsh) understand me as not being’ (R4).

The following will report both the overall responses and the variations in responses by EU/non-EU and Anglophone/non-Anglophone respondents. Reference will also be made to the free-text responses in order to contextualise the quantitative with qualitative empirical information.

(b) Focus of research and teaching

This section concentrates on the question of whether the respondents are keen to make use of their foreign legal education or whether they rather feel that they should fully assimilate to the UK legal environment. The former view would be in line with a statement by Christopher McCrudden that the ‘multi-national nature of UK legal teaching has undoubtedly contributed to the development of a more cosmopolitan legal education’.Footnote 39 It may also be argued that the specific historical experience of German-speaking émigré lawyers who fled from Nazi Germany in the 1930s may point in a similar direction, as they are said to have had a strong tendency to emphasise the commonalities of people from different countries, races and religions.Footnote 40 However, others have suggested that the Jewish émigré lawyers had a strong wish to assimilate, namely that there was a ‘temptation to present themselves as being more English than the English’.Footnote 41 This latter position may also be confirmed by a statement from higher education research that (only) the sciences share ‘common languages and research programs worldwide’,Footnote 42 while legal scholars who move to another country may feel the need to change their research focus to their new country's law.

The first and second survey questions thus asked respondents to reflect on the role of the law of their home jurisdiction in their research and teaching. In the introductory remarks to the survey, it was clarified that the survey ‘(…) is addressed to UK-based legal scholars who did their initial law degree (LLB, JD or equivalent) in another country (in the following: “your home jurisdiction”)’.

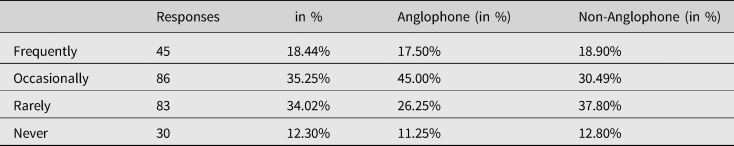

Question 1 asked about the frequency of their research dealing with the law of their home jurisdiction (see Table 3). It can be seen that the two options in the middle were the ones chosen most frequently. Thus, most respondents say that some of their research concerns the law of their home jurisdiction. Aggregating the options ‘frequently’ and ‘occasionally’, it can be seen that 62.50% of Anglophone scholars fall into these categories, while the figure is just below 50% for non-Anglophone scholars.Footnote 43 Indeed, it makes sense that the research of Anglophone scholars more frequently relates to their home jurisdiction as these latter rules may also be relevant for UK (or English, Welsh etc) law given the survival of a ‘single common law tradition’ despite local deviations.Footnote 44

Table 3. Question 1: ‘How far does your research deal with the law of your home jurisdiction (as opposed to UK law, international law etc)?’

As regards the non-Anglophone scholars, it is notable that the highest category (‘frequently’) has been chosen even more often than by Anglophone scholars. This is likely to account for cases where a scholar's expertise in a foreign jurisdiction is their main interest of research. According to one respondent, ‘I work as a comparatist, so, French law (as it is the place I trained) is used frequently’ (R39). And according to another one:

‘I guess answers to the first two questions may differ based on the importance of the home country in comparative studies, funding applications, and student composition. E.g., colleagues with Chinese origin often research and refer to Chinese law given high demand. The interest in legal developments in post-Soviet countries is lower’ (R57).

Two responses also emphasise the potential benefit of being trained in a civil law jurisdiction – but also the challenges of being based in the UK. In the first, it is said that ‘I find having a civil law background helps me explain and I sometimes use examples and illustrations from outside common law’ (R56). The second one starts with the statement that ‘it would be good for the UK legal culture to be more exposed to serious doctrinal analysis of continental law’ but then also adds that ‘(t)here is a mistaken sense that the common law is very different’ (R1).

According to the wording of Question 1, the alternative to research on foreign law is any other engagement with legal rules. Some of the respondents clarified that, for them, this alternative is not UK law but, for example, general jurisprudence, EU law or international law (R21, R41, R42, R53). It may then well be the case that, as suggested by one of the respondents, the divide is often between legal scholars who pursue research in UK law and everyone else (R20), also considering that, according to another respondent, ‘since I research and teach EU law, I occasionally use many jurisdictions etc as an example as well’ (R33). In this respect it is furthermore interesting to note that legal scholars may shift their focus due to Brexit (addressed in more detail in the following section). According to one of them:

‘I am [also] concerned about my EU focussed research not being as seriously considered or losing opportunities in Europe. I have had to start internalising my research (U.K. focussed) and also started focussing more on international law to future-proof my research position.’ (R8)Footnote 45

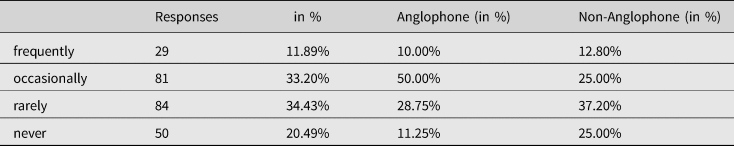

The general pattern of responses to Question 2 about the frequency of teaching aspects of the law their home jurisdictions (see Table 4) resembles that of Question 1, though at a slightly lower level for Anglophone scholars and at a considerably lower level for non-Anglophone scholars.Footnote 46 Specifically, it can be seen that 60% of the Anglophone foreign-trained legal scholars report that they incorporate aspects of the law of their home jurisdictions ‘frequently’ or ‘occasionally’, while this is less than 40% for the non-Anglophone legal scholars.Footnote 47

Table 4. Question 2: ‘How far do you incorporate aspects of the law of your home jurisdiction in the undergraduate or postgraduate teaching at your UK university?’

Despite some divergences, the continuing similarities of common law countriesFootnote 48 mean that legal scholars trained in other common law countries can make use of their prior legal education in teaching many courses at UK universities. As expressed by one of the respondents:

‘There is some usefulness to being from a common law jurisdiction in my home jurisdiction. I think there is a perception that I can teach more subjects than my colleagues who are foreign-trained but from civil law jurisdictions.’ (R31)

This does not mean that there are no differences in the way common law scholars approach the teaching of a particular subject in the UK. According to another respondent, ‘it is clear’ that Australian legal scholars follow developments in UK law while UK legal scholars are ‘highly unlikely to follow Australian developments and especially not to include in UG teaching’ (R50). It is also possible, but beyond the scope of the survey, that foreign-trained legal scholars from other common law jurisdictions incorporate diverse modes of teaching (eg US-trained legal scholars may use Socratic teaching methods or reflect the postgraduate nature of US legal education).

Beyond the common law, some respondents explained why they do, or do not, include the law of their home jurisdiction. For example, on the one hand, a respondent stated: ‘I teach on a French law programme as well as a comparative contract law module, so, it is frequently used’ (R39). On the other hand, some of the international law scholars clarified that incorporating elements of law from their home jurisdictions is not really an issue (R21, R28) (while one could also take a different position given the rise of ‘comparative international law’Footnote 49). With respect to EU law, a respondent pointed out that they had ticked the option ‘rarely’, as EU law ‘is technically still part of UK law’ (R41) (or at least it was at the time the survey was circulated).

For foreign-trained legal scholars who have a civil law background and are asked to teach common law subjects, it remains a challenge to teach something they have never studied. In particular, this may be challenge if we follow Pierre Legrand's view that civil and common law are based on irreducibly different ways of understanding.Footnote 50 According to Legrand, it is impossible for a civil law lawyer to think like a common law lawyer, or vice versa,Footnote 51 and a civil law lawyer ‘can never understand the English legal experience like an English lawyer’.Footnote 52 Of course, this does not imply that it is impossible to learn something new; yet, in the spirit of Legrand, the argument would remain that the original legal background of scholars will always shape their ways of legal thinking, as is the case for our native languages when we learn a foreign one.Footnote 53

However, it is also possible to take a more optimistic view, as is also expressed in the comparative law literature. For example, it is said that legal systems should not be seen as ‘closed frameworks’ that foreigners can never enterFootnote 54 and that the ‘borders of legal systems are not the borders of knowledge acquisition’.Footnote 55 Likewise, the parallels with language learning are not conclusive, since a native language is acquired as an infant, while law is studied as an adult. For legal learning, it is suggested that we can be more optimistic and follow the view that it is possible to overcome national legal cultures. Specifically, by identifying legal culture as ‘mental software’, it is possible that ‘mental programming’ can accommodate different cultural perceptions.Footnote 56

The UK universities themselves largely seem to follow this more optimistic view, as they frequently appoint civil law trained scholars and ask them to teach common law subjects. Yet, there is also the potential that foreign-trained legal scholars face various problems, as we will see in the next section.

(c) ‘Trouble in paradise’?

In the higher education literature, it is observed that foreign academic qualifications can be either an advantage or a disadvantage. On the one hand it is said that ‘international mobility is increasingly valued on a CV’ and that their ‘mobility experience’ may lead to ‘privileged positions in academia’.Footnote 57 On the other hand, internationally mobile scholars may ‘experience skill downgrading, ending up in relatively lower positions in the labour market in the destination country’ with their ‘educational qualifications as a form of institutionalised cultural capital’ being insufficiently acknowledged by their colleagues.Footnote 58

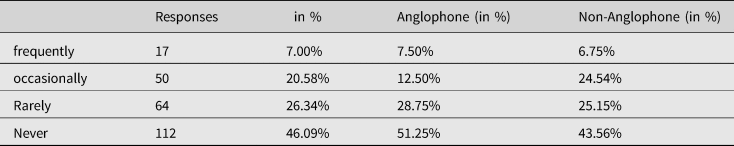

The responses to Question 3 show that only a minority of foreign-trained legal scholars report ‘frequent’ or ‘occasional’ discrimination (see Table 5). Comparing Anglophone and non-Anglophone scholars, the rate is higher for the latter group (31.67% as compared to 20%).Footnote 59 From a critical perspective, these data may also be read as stating that only a minority of respondents have ‘never’ experienced discrimination. Finally, the importance of analysing forms of discrimination is confirmed by the fact that many of the free-text responses of the survey addressed the topic of this particular question.

Table 5. Question 3: ‘Have you experienced discrimination as compared to (fully) UK-trained colleagues?’

Some of the free-text responses refer to the appointment process at UK universities. According to one of them, the applicant was challenged as being ‘qualified to teach law in England and Wales’ (R48), and in another response the extensive foreign experience of ‘both teaching and research’ was said to be ‘somewhat overlooked’ (R10). Yet, most other comments on the appointment practices applaud the general willingness of UK universities to appoint foreign-trained legal scholars; or, for example, saying that they ‘welcome excellent scholarship from international colleagues to a far greater extent than other academic systems do (e.g., US, many continental European) do’ (R61) and that the ‘UK seems to me to be among the, if not the, most welcoming jurisdiction for foreign trained law academics’ (R36). A further response starts with a similar positive statement but then also expresses a strong form of criticism:

‘UK universities are, unlike US ones, more open to hiring foreign-trained academics, even when it comes to teach UK law. This is certainly something to be commended and that is not found anywhere in Europe – certainly, for example, not in legal academia in countries such as Germany, France and Italy. And yet UK academics often display a very “British empire” approach to international colleagues – i.e., they very rarely seem to fully appreciate and understand the diversity of foreign colleagues and the potential cultural enrichment they bring to the table. In other words, and beyond catchphrases on diversity etc., UK academia is welcoming toward foreign-trained scholars as long as they are willing to be assimilated.’ (R59)

In some of the responses, a lack of appreciation of the ‘foreign’ is expressed even more strongly: one of them says that ‘casual racism/microaggressions’ are real problems in UK academy (R12) and another one refers to ‘stigmatising attitudes towards my home country on the part of some colleagues’ (R61).

More often, however, respondents referred to a variety of more indirect and institutional disadvantages that are faced by foreign-trained legal scholars. Some of them concern specific problems of non-Anglophones scholars. According to one of them, ‘cultural and linguistic barriers exist’ and it ‘takes some time and emotional energy to catch up with all the aspects of the UK educational system’ (R11). And, according to another one:

‘Non-native English speakers are examined and assessed for promotion under the same standards applied to their native-English speakers colleagues. Yet, since all the important publications are in English, for a non-native speaker it takes on average two to three times more to write a book or an essay. This is a de facto discrimination because foreign trained academics will take more time to reach the number of publications required for promotion.’ (R43)

Another respondent refers to teaching assessments as an example of discrimination, namely that research shows that ‘non-UK staff always received worse student feedback than UK staff’ (R24) which then also matters for performance benchmarks. Presumably, this mainly applies to non-Anglophone foreign-trained legal scholars,Footnote 60 in particular as far as undergraduate teaching is concerned (given that postgraduate students are often also non-native speakers in English).

The UK's Research Excellence Framework (REF) is also mentioned as a possible source of discrimination. In one of the free-text responses it was said that the REF has a ‘huge impact on what is seen as quality research, including what topics and jurisdictions are discouraged’ (R38), and it is then likely to matter that, according to another response, in the UK ‘other legal orders are not seen as just different but almost always inferior’ (R62).

Finally, some of the respondents use the adjectives ‘soft’ and ‘subtle’ in order to indicate the problems of identifying discrimination.Footnote 61 For example, this may refer to situations where there are ‘different reference points’ and ‘not completely understanding what is being communicated’ (R27). It can also be about forms of exclusion, for example ‘conference invitations not sent, editorships kept within small elite British group, projects not shared, teams not joined etc’ (R29) or, according to another respondent, ‘occasional discrimination for not being British when it comes to senior positions, such as Head of Department or higher’ (R45).

In conclusion, it can be seen that there are a variety of reasons why some discrimination exists to the detriment of foreign-trained legal scholars in the UK. This paper cannot examine how far the reasons mentioned by some respondents are representative of the overall population of foreign-trained legal scholars. It should also be noted that in some instances efforts are made to avoid discrimination. For example, the REF system accepts publications on any topic and published in any language, and the author of this paper is aware that, in some universities, this is not discouraged and efforts are undertaken to ask foreign experts to review the ‘REFability’ of these publications. It is also at least possible that parts of the REF could actually favour foreign-trained legal scholars: for example, international and comparative research may have a better chance of being regarded as ‘internationally excellent’ and may thus more often receive a classification of at least as ‘three star’ than research which ‘merely’ deals with one jurisdiction.Footnote 62

Brexit has a direct discriminatory impact on UK-based EU academics who do not hold UK citizenship. In light of the result of the Brexit referendum, the impact that Brexit will have on UK higher education in general and legal education in particular has been discussed.Footnote 63 Specifically, in a 2016 survey, 76% of non-UK EU academics stated that ‘they were more likely to consider leaving UK higher education’.Footnote 64 For legal scholarship and education, a 2017 blog post by Jessica Guth suggests that the loss of EU students and staff could be ‘devasting’, leading to, among other things, ‘a more inward looking and insular approach to scholarship and teaching’, ‘less tolerance for different ideas and approaches and ways of thinking’ and ‘less well rounded lawyers’.Footnote 65 Thus, revisiting the possible impact of Brexit by means of the survey was also seen as worthwhile, for the purposes of this paper.

Question 4 asked respondents to indicate whether they are considering leaving the UK, and some of the free-text responses also addressed the impact of Brexit more generally. It can be seen that a majority answered in the affirmative (see Table 6). As expected, the foreign-legal scholars who trained in EU countries are even more willing to leave, with only 22% explicitly stating that they are not considering leaving the UK. It is, however, also interesting to observe that almost 40% of non-EU legal scholars indicate that they are considering leaving the UK due to Brexit.

Table 6. Question 4: ‘Does “Brexit” make you consider leaving the UK?’

Some of the free-text comments of respondents who do not plan to leave the UK clarify that they do not regard Brexit as a positive development. Rather they refer to personal reasons and problems of relocating elsewhere. For example, according to one of them, the UK is now ‘the place where my contacts with various legal practitioners are’ and ‘where my children go to school’ (R47; similarly referring to family reasons: R2, R14, R39). According to another, ‘leaving the UK owing to Brexit is very difficult to do it in practice for those of us that have established our lives and have been truly EU integrated, i.e. we now are couples that are British and of nationals of another EU MS, and have children’, while then also referring to the closed nature of academic job markets in continental Europe (R15).

Some respondents also clarified that they joined UK academia post-Brexit (R53, R57). Indeed, another respondent mentioned that, in several post-Brexit recent recruitment rounds, ‘there seemed a continued interest from European legal scholars to work in the UK’ (R34). Similarly, a journal article explains that many of the reasons why mobile academics find the UK an attractive destination are not immediately impacted by Brexit, stating that ‘the language, career opportunities for entry and mid-level academics, and the openness of the market are likely to remain stable’.Footnote 66

As regards EU scholars who are considering leaving the UK, the free-text responses refer to a variety of factors. One of the respondents expresses ‘concerns about the future of funding opportunities, working conditions and security of tenure’ as well as ‘EU focussed research not being as seriously considered or losing opportunities in Europe’ (R8).Footnote 67 Another states that they are actively considering leaving the UK while also saying that ‘this does pose some professional “anxiety” insofar as I have focused mainly on UK, EU and international law (…) and naturally neglected my home jurisdiction’ (R3). As a final example, a legal scholar originally from Ireland expresses the lost advantage of the EU muting ‘some of the historic tension between the UK and Ireland’ and ‘working with UK and other colleagues on comparative law projects’ (R65).

Two non-EU scholars who are considering leaving the UK provide some further reasons related to UK universities and the UK as a country more generally. According to the first one, ‘the pressures placed on the academic sector in recent years (of which Brexit is only the most recent) has resulted in a system that is dominated by middle managers working from a professional services perspective that is frequently antagonistic to academic research excellence and a reasonable life/work balance’ (R61).Footnote 68 And according to the second, ‘Britain is radically changed’ since the referendum, having become ‘a poorer, nastier country with a growing intolerance to those who are from elsewhere’ (R22).

It is beyond the scope of this paper to assess whether these latter statements are representative of all foreign-trained legal scholars in the UK. Yet, they illustrate well that – akin to the reasons why foreign-trained legal scholars moved to the UK in the first placeFootnote 69 – a variety of factors play a role in a complex manner. It is too early to say how this will change UK legal academia. At present, it seems likely that it will retain its unique feature of having a large number of foreign-trained legal scholars. Yet, as universities in the EU and elsewhere come to realise that there are many highly qualified legal scholars in the UK who are keen to relocate to another country, this may well change in the long run.

4. Conclusion

In recent years and decades, a growing volume of research has discussed the nature of legal scholarship and what it means for legal scholars as both researchers and teachers. For example, many publications discuss how far traditional ‘doctrinal’ and ‘black-letter’ methods of legal scholarship have been challenged by socio-legal, critical, economic and others forms of interdisciplinary legal research.Footnote 70 A further point of discussion has been the relationship between legal scholarship and the legal profession. Here, it has been bemoaned by some that US legal scholarship has moved too far away from the actual law, resulting in a growing disjunction between US law schools and the legal profession,Footnote 71 while in continental European the interaction between these two groups may still be fairly strong.Footnote 72

Returning to the topic of this paper, it could be argued that the prevalence of many foreign-trained legal scholars in the UK might have a negative influence on interdisciplinary legal scholarship, in that they may have received their original legal education in a country with an emphasis on ‘doctrinal’ and ‘black-letter’ methods. Moreover, as foreign-trained legal scholars are likely to be less connected to UK legal practice than their locally trained colleagues, there could be a further disadvantage in that it might lead to a growing disjunction between legal academia and legal practice in the UK. For the same reason, the mismatch between foreign-acquired legal training and the task of teaching domestic law could be disadvantageous to law students. Thus, such line of reasoning would consider foreign-trained legal scholars as ‘irritants’Footnote 73 to UK legal scholarship and education.

However, there are better reasons to follow the positive view that foreign-trained legal scholars are ‘change agents’ in their UK universities. As some of the answers to the first two questions of the survey indicate, a good number of foreign-trained legal scholars use the law of their home jurisdiction as a point of comparison for research and teaching. This is important, as comparative law typically goes hand-in-hand with socio-legal or other interdisciplinary approaches to legal scholarship, given that analysis of legal differences and similarities is likely to be assessed alongside non-legal differences and similarities.Footnote 74 What is more, the use of comparative information is a key factor that makes ‘law’ an academic discipline. In the words of Jan Smits, ‘all disciplines aim for knowledge that supersedes the local: academic work aims for universal knowledge and is therefore necessarily international’.Footnote 75 This does not mean that legal research cannot be concerned with local knowledge (eg the laws of a particular country). Yet, foreign-trained legal scholars may then push UK legal academia to reflect on, say, what the discussion about the interpretation and application of a particular rule of English law means for legal knowledge more generally.

Finally, it would not be convincing to argue that foreign-trained legal scholars create a growing disjunction to legal practice and that they are ill-equipped to teach UK law. In today's world, legal practice is increasingly transnational, at least in some fields. Thus, having some foreign legal background may be an advantage for foreign-trained legal scholars as far as they teach, for example, topics of financial law. In other instances, they can at least provide students with an international perspective about law more generally which can be relevant for any future career (whether in legal practice or elsewhere). It may also be noted that, as foreign-trained legal scholars have chosen to live and work in the UK, many of them do have an interest in UK law (or English, Scots law etc). Thus, it would be unfair to assume that they never interact with UK legal practice and are reluctant to teach UK law. Furthermore, some, or even many, UK-trained legal scholars are (also) not particularly close to legal practice;Footnote 76 thus, responding to the US debate mentioned at the beginning of this section, it can be argued that in the UK the more practical legal training will, in any case, follow at a later stage for those LLB graduates who aspire to become solicitors or barristers/advocates.

As a result, despite the problems highlighted in the responses to the third and fourth survey questions, it is suggested that the UK model of having a large proportion of foreign-trained legal scholars at its universities has largely been a success story. Accordingly, as UK universities have shown a greater openness to appointing foreign-trained legal scholars, this may well be a model for other countries.

Annex

(a) Cover email sent on 27 November 2020

Subject line: Survey on Foreign-Trained Legal Scholars in the UK

Dear [CustomData1],

Hope all is well and apologies for the request to respond to a survey in these difficult times. But this survey is really a very short one :-), with just four multiple choice questions which takes less than one minute to complete (see button ‘Begin Survey’ below).

Thank you for your time and all the best,

[….]

(b) Survey text (as made available on Surveymonkey)

Survey on Foreign-Trained Legal Scholars in the UK

This short survey is addressed to UK-based legal scholars who did their initial law degree (LLB, JD or equivalent) in another country (in the following: ‘your home jurisdiction’). This survey is carried out in compliance with the EUI Code of Ethics in Academic Research and all responses will be treated strictly confidential and anonymous.

Q1: How far does your research deal with the law of your home jurisdiction (as opposed to UK law, international law etc)? (i) frequently; (ii) occasionally; (iii) rarely; (iv) never

Q2: How far do you incorporate aspects of the law of your home jurisdiction in the undergraduate or postgraduate teaching at your UK university? (i) frequently; (ii) occasionally; (iii) rarely; (iv) never

Q3: Have you experienced discrimination as compared to (fully) UK-trained colleagues? (i) frequently; (ii) occasionally; (iii) rarely; (iv) never

Q4: Does ‘Brexit’ make you consider leaving the UK? (i) yes; (ii) no; (iii) I don't know; (iv) not applicable

Q5: Do you have any other comments (whatever it may be; I'm aware that the four questions above may seem limited in scope)? Free text

(c) Respondents who answered Q5

Note: for reasons of confidentiality no further details on the background of the respondents are disclosed.