Introduction

Does democracy aid influence whether democratisation helps – or hampers – building peace after civil war? For almost three decades, support for democratisation constitutes an integral part of international peacebuilding efforts.Footnote 1 This seemed a fruitful strategy in Nepal (2006) and Nicaragua (1991), but less so in Liberia (1997) or Angola (1992). The long-held conviction that democratisation is the best path towards stable peace after civil wars has increasingly been questioned.Footnote 2 Based on findings that democratisation processes are particularly conflict prone, scholars concluded that political liberalisation – and efforts to support this end – may cause renewed violence.Footnote 3

This article contributes to the debate on the wisdom or folly of supporting democratisation after civil war. It generates new insights on the potential of postconflict democracy aid through a novel approach: First, it is the first to disaggregate democracy aid, which allows exploring the effect of external support targeting key aspects of postconflict democratisation that are either peace-enhancing or peace-threatening. Second, it proposes that combinations of such support can help to prevent destabilising effects. Third, it investigates the postconflict context where the destructive dynamics are supposedly most pronounced. Overall, it explores the following research question: What kind of external democracy aid (if any) can alleviate destabilising consequences of democratisation after civil war?

While the effect of democracy aid on democratisation has received much attention, we know little about its role in fostering peace after civil war. Roland Paris argues that externally supported liberalisation triggered renewed violence in several qualitative case studies.Footnote 4 Quantitative studies suggest that such support might trigger low-scale violence, but is statistically associated with a reduced likelihood of civil conflict during regime transition.Footnote 5 However, these analyses do not specifically consider postconflict situations, and use an aggregate measure of democracy aid.

Combining fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) with insights from a qualitative case study, this article identifies patterns of democracy aid that explain peaceful democratisation after civil war. QCA is uniquely equipped to analyse complex causal relationships because it allows focusing on the combined effect of the presence and/or absence of various factors. Moreover, it acknowledges that alternative pathways (that is, combinations) can lead to the same outcome. Drawing on forty qualitative interviews with domestic and international stakeholders, the Liberian case serves as a plausibility probe of the finding with the widest explanatory scope.

The findings suggest that external democracy aid can indeed help to sustain peace during postconflict democratisation. More specifically, promoting ‘controlled competition’ through combined substantial support for institutional constraints and for competition explains peaceful democratisation after civil war even in most difficult cases. In countries without a high predisposition for conflict recurrence, fostering ‘cooperative democratisation’ by substantially supporting cooperation alone might be able to prevent renewed violence. Importantly, the analysis indicates that democracy aid is not associated with renewed violence. The results not only contribute to the academic debate, but also provide useful insights for policymakers.

The article proceeds as follows: The next section discusses existing literature accounts on the relationship between (postconflict) democratisation and peace. Section three discusses the dynamics of postconflict democratisation in view of how democracy aid can reinforce peace-enhancing and mitigate destabilising effects. After presenting the research design in section four, the fifth section discusses the results before the last draws a conclusion.

Postconflict democratisation

A democratic system, following Robert Dahl's notion of polyarchy, is characterised by public participation and contestation, accompanied by institutional guarantees.Footnote 6 I define postconflict democratisation as an improvement in the quality of one or more of these aspects, in the aftermath of a civil war. Democratisation, as understood here, does not imply that full democracy is reached at the end of the process. It depicts a ‘process of opening up of political space’,Footnote 7 which can mean the introduction of democratic institutions in an undemocratic regime, or the deepening of democratic qualities of an already rather democratic regime (without a guarantee against subsequent backsliding). Although democratisation processes are primarily driven by domestic actors and institutions, research shows that external actors can effectively foster democracy.Footnote 8 I follow Azpuru, Finkel, Pérez-Liñán, and Seligson in defining official development assistance as democracy aid if it is specifically targeted at democracy promotion and aims at ‘establishing, strengthening, or defending democracy in a given country’.Footnote 9

Theoretical arguments paired with empirical evidence suggest that consolidated democracies are least susceptible to violent conflict. Theoretically, democracies provide mechanisms for peaceful conflict resolution.Footnote 10 Empirically, numerous studies demonstrate that full democracies – as well as full autocracies – rarely break down.Footnote 11 Moreover, recent studies suggest that the quality of political institutions or higher governance levels has a significant impact on preventing the recurrence of civil war.Footnote 12 Yet, empirical evidence also indicates that the path towards democracy is often far from smooth despite the positive effects an established democratic system can have on maintaining peace.

Scholars have demonstrated that transition processes contain destabilising potential,Footnote 13 in particular after violent conflict.Footnote 14 Case studies supported these macro-level findingsFootnote 15 and point to trade-offs between establishing peace and democratisation.Footnote 16 Cederman, Hug, and Krebs address concerns regarding the reliability of the statistical resultsFootnote 17 and confirm the relationship using a more valid measurement of regime change.Footnote 18 While agreement is still lacking as to how strong the relationship between democratisation and instability is, consensus holds that processes of democratisation contain the potential to destabilise.

Against this background, the question arises whether democracy aid fosters, or hampers, building peace after civil war. Externally supported democratisation has been at the centre of international peacebuilding since the 1990s. Renewed violence in many cases, however, triggered a critical debate regarding this ‘liberal peacebuilding’ strategy, arguing that promoting democracy to foster peace is unsuited for fragile, war-torn contexts.Footnote 19 Various scholars caution that in postconflict situations democracy aid might actually run counter to building peace and should at least be postponed until the circumstances are more favourable.Footnote 20 Burcu Savun and Daniel Tirone's statistical finding that democracy aid significantly reduces the likelihood of violence during transition, though, provides ground for optimism.Footnote 21 They argue that democracy-related aid can reduce problems of uncertainty and commitment. Similarly, Aila Matanock shows that democratic participation provisions in peace agreements combined with close international scrutiny can reduce the risk of renewed violence.Footnote 22 Sebastian Ziaja, in turn, finds an ambivalent effect: He demonstrates that democracy aid is associated with higher levels of violent unrest, though not with the outbreak of civil war.Footnote 23 Yet, except for Matanock, these studies concentrate on democratising countries in general and do not differentiate those cases whose recent history of civil war renders them particularly vulnerable to experience renewed violence.Footnote 24

In sum, previous research on the peace-democracy nexus investigated the effect of democratisation on peace,Footnote 25 the effect of postconflict elections on peace,Footnote 26 or the effect of democracy aid on postwar democratisation.Footnote 27 Scholars have provided robust findings that democracy aid fosters democratisation,Footnote 28 and that it can mitigate destabilising effects of democratic transitions.Footnote 29

However, the literature lacks conclusive evidence for the effect of democracy aid on the chances of civil war recurrence. The existing macro-level studies do not take the postconflict context into account. Moreover, they analyse aggregate Official Development Assistance (ODA) contributions. Due to the complexity of the peace-democracy nexus that lacks a clear, linear relationship, this article assumes that focusing on the effect of aggregate aid levels is insufficient. Instead, it might be necessary for international support to reinforce the peace-enhancing aspects as well as addressing adverse dynamics of postconflict democratisation to prevent a recurrence of violent conflict. I therefore disaggregate democracy support to allow a more fine-grained understanding of which type and combination of support (targeting specific aspects of democracy) can explain peaceful democratisation after civil war.

Democracy aid

Drawing on research in the fields of regime transition and conflict research, I argue that substantial (as compared to marginal) support for competition, for institutional constraints, and for cooperation can help to mitigate, but might also reinforce destabilising dynamics of postconflict democratisation. Due to the complexity of the relationship between peace, democracy, and democratisation, I theorise that strengthening one aspect only might be insufficient or potentially even counterproductive. Instead, combinations of support might be necessary to render democratisation peaceful.

Democracy aid can impact on postconflict political processes in various ways. First, financial contributions and technical support can help to improve the functionality and capacity of democratic institutions, processes, and actors,Footnote 30 for example, through civic education,Footnote 31 or support for civil society.Footnote 32 Moreover, financial support can be crucial to reduce the dependence of actors and institutions on the ruling government, allowing them the necessary independence to oppose the government or hold it accountable.Footnote 33 Second, international engagement in an area can help to improve the credibility and legitimacy of democratic procedures.Footnote 34 Third, international attention and scrutiny will be heightened by support in an area, which can help to facilitate cleaner democratic procedures and mitigate the risk of violence.Footnote 35

Competition

Support for competition can strengthen peace-enhancing aspects of democratisation; by facilitating free and fair competition for power, for example through electoral support, or empowerment of marginalised groups.Footnote 36 Promoting pluralism that allows a meaningful choice can make an important contribution to the open political contestation that is essential for a functioning democracy.Footnote 37 External support can enable a (more) level playing field where diverse political actors have a fair chance of gaining power, for example by promoting a free and vibrant press thereby helping to facilitate a genuine debate or empowering marginalised groups and civil society organisations to promote pluralism and a meaningful choice.

Democratic procedures in turn can work as a system of conflict management. Since conflicts exist in every society, the main question is whether a society is able to resolve them in a peaceful way. Functioning democratic institutions offer mechanisms to deal with conflict peacefully, in contrast to autocratic regimes, which often rely on repression. Democratic elections and accountability mechanisms provide institutionalised, transparent, and open channels to allocate, but also withdraw political power.Footnote 38 This way, supporting democratic procedures provides non-violent means to address grievances and seek government reform, allowing former rebels or other groups outside the power circles to influence politics without adhering to violent strategies.Footnote 39

In addition to procedures for managing conflict, a democratic system also directly reduces sources of conflict. It gives a voice to different groups, reducing exclusion and marginalisation, which are key reasons for conflict recurrence.Footnote 40 Targeted support for these groups can help to make their participation meaningful. Thus, fostering political competition reduces the incentives for groups that do not hold power to violently challenge power-holders.

Potential power gains for one group, however, imply potential power losses for another. Strengthening an independent electoral commission, providing technical support to facilitate clean and transparent elections or sending election observers reduces opportunities for electoral fraud.Footnote 41 Thus, external support for competition can help emerging political actors to effectively challenge power-holders. If as a consequence of such support the ruling elite feels seriously threatened, it may provoke repressive responses and unleash violent dynamics, since power-holders – be they old elites or new, democratically elected incumbents – seldom yield their power and privileges voluntarily.Footnote 42

Thus, I expect that external support for competition alone is insufficient to sustain peace during postconflict democratisation and might even trigger renewed violence.Footnote 43 To avoid reinforcing the adverse effects of increased political competition, it might be necessary to combine different types of democracy aid. The postconflict context reinforces the potential of such destabilising dynamics. High degrees of polarisation and mistrust increase the chances that the competitive nature of liberal democracy triggers renewed violence.Footnote 44 Moreover, subjugating to democratic rules could mean accepting defeat at the ballots after winning on the battlefield.Footnote 45 This makes it difficult to believe that all actors credibly commit to these rules, and that neither the winning party would usurp power nor losers return to warfare.Footnote 46 Therefore, strengthening institutional constraints and fostering cooperation might be important additions to promoting political competition.

Institutional constraints

First, I theorise that combining support for competition with support for institutional constraints can foster the peace enhancing effects of postconflict democratisation. It can address the institutional vacuum caused by a democratic transition, countervail the credible commitment problem and raise the costs of violent competition. Support for institutional constraints can help to effectively thwart abuses of power.Footnote 47 For example, by enabling an independent judiciary to prevent momentary electoral winners from using their legitimately gained power to entrench their position. Peaceful contestation and the acceptance of unwelcome or unexpected results are more likely if the opposition sees a fair chance to win power in the next elections.Footnote 48 Moreover, a functioning judicial system can act as a neutral arbiter of clean electoral procedures and offer non-violent means to address (alleged) fraud or procedural deficiencies. Promoting the neutrality and democratic oversight of the police can help to ensure the impartial persecution of undemocratic behaviour. In a postconflict context, those institutions formerly able to contain or punish violence are usually weakened or dismantled while nascent democratic institutions typically fail to provide effective constraints and credibly guarantee that the rules will be upheld for all actors alike. External support can be essential to strengthen institutional constraints since the ruling elite will mostly be disinclined to strengthen checks on their own power.Footnote 49 Moreover, guaranteed rights and freedoms directly reduce grievances and prevent the repression of minority groups and divergent opinions.

Strengthening institutional constraints in the absence of political pluralism and fair contestation, however, might be similarly unsuited to foster peaceful democratisation. Institutional constraints can be used for repression as well as for protection. If the judiciary or the police are under the influence of the ruling party, they may become tools for monopolising and retaining power rather than constraining abuses of power.Footnote 50 Since power-holders have little incentives to allow the creation of effective constraints on their own rule,Footnote 51 political contestation might be required to foster the independence and neutrality of oversight institutions. International support for pluralism alongside support for institutional constraints can help to strengthen the role of an opposition currently not in power, a critical media as well as the awareness of power-holders that a different party might gain power in the future. It thus reduces opportunities and incentives to engage in violence both for power-holders as well as for contenders or marginalised groups. Thus, I expect that a combination of support for institutional constraints and for competition is required to mitigate negative, and instead generating peace enhancing effects of postconflict democratisation.

Cooperation

Second, I expect that supporting cooperation in society can be another way to mitigate the potential destabilising effects of political competition. Electoral competition requires mobilising constituencies, which entails emphasising differences instead of similarities. After protracted conflict, mobilisation strategies tend to exploit, and thereby reinforce, wartime cleavages by stoking rivalry, drawing upon hatred and antagonism.Footnote 52 Substantial support for cooperation can countervene divisive mobilisation strategies by reducing the fertile ground for such tactics. Support in this area, moreover, can help to generate the basic consent to a political system that places a premium on compromise and is not perceived as a zero-sum game.Footnote 53 As a consequence, it can soften the credible commitment problem and increase the chances that constituencies accept electoral defeat of their candidates without violent contestation. The trust that electoral winners will not use their temporary superiority to restrict competition for power is pivotal for momentary losers to respect ‘the winners’ right to make binding decisions’.Footnote 54 Therefore, it is plausible that substantial support for competition combined with efforts to promote cooperation can help to render postconflict democratisation processes peaceful.

Third, combining substantial support for institutional constraints and cooperation might theoretically also mitigate destabilising effects of postconflict democratisation. The two kinds of support could mitigate violence by addressing the credible commitment problem and thus crucially strengthen emerging democratic procedures.

In short, based on the theoretical discussion we should expect that support for two of the three conditions jointly can facilitate peaceful democratisation after civil war. Each of the combinations constitute alternative pathways to peace. In QCA notation: COMP*IC + COMP*COOP + IC*COOP → PEACE (combined support for competition and for institutional constraints, or for competition and for cooperation, or for institutional constraints and cooperation is sufficient for peaceful democratisation).Footnote 55 With regard to recurrence, we expect that one type of support alone is insufficient to prevent renewed violence. Thus, only supporting competition without supporting institutional constraints nor cooperation is insufficient to facilitate peaceful democratisation (thus leading to recurrence), as is the sole support for institutional constraints or for cooperation alone: COMP*~IC*~COOP + IC*~COMP*~COOP + COOP*~IC*~COMP → RECURRENCE. The subsequent analysis includes a formalised theory evaluation to appraise these expectations against the empirical reality.

Contextual factors

Various factors can theoretically matter for the effect of international democracy promotion efforts on peace. Inclusive institutional designsFootnote 56 and demobilisation of rebel groups can help to reduce the credible commitment problem present in postconflict democratisation processes.Footnote 57 In these contexts the importance of external democracy aid might be reduced, but its effect could also be enhanced. In addition, higher levels of development, previous democratic experience and stronger institutions heighten the chances of successful postwar democratisation.Footnote 58 Income and geostrategic importance may limit the leverage donors can have, reducing the potential impact of external democracy promotion.Footnote 59 Furthermore, we know that various factors related to characteristics of the previous conflict as well as several structural context conditions such as the level of socioeconomic development increase the risk of civil war recurrence.Footnote 60 Contexts with a particular high risk of conflict recurrence might increase the importance of external engagement, though also reducing its chances to succeed.

Research design

Using Qualitative Comparative Analysis on all 18 cases of postconflict democratisation in the period 1990–2014, this article generates new insights on the role of democracy aid in fostering peace after civil war. To assess the plausibility of the findings, qualitative insights from Liberia complement the QCA. Liberia exemplifies the path with the widest explanatory scope, covering a large share of cases including most difficult cases. The discussion draws on forty qualitative interviews with international representatives and domestic stakeholders from politics, civil society, and media conducted in Monrovia at the end of 2017.

Qualitative Comparative Analysis

This article asks what kind of external democracy aid (if any) can alleviate destabilising consequences of democratisation after civil war. It assumes that different combinations of democracy aid can influence whether postconflict democratisation triggers renewed violence.

QCA is ideally suited to address the research problem: The set-theoretic approach allows going beyond the probabilistic logic of linear regression analysis, which has hitherto dominated the debate on the peace-democracy nexus. By focusing on configurations instead of correlations, QCA is able to handle three core aspects of causal complexity and is uniquely equipped to provide new insights on this complex relationship.Footnote 61 Its epistemology acknowledges (1) that different causal paths can lead to the same outcome (equifinality); (2) that a condition (often) exerts a certain effect only in combination with other conditions (conjunctural causation); and (3) that the absence of a condition does not necessarily have the inverted effect of its presence (asymmetric causality).Footnote 62 In other words, it is plausible to expect that not a single remedy can sustain peace in all postwar democratisers; that the effect of one type of democracy aid might depend on the presence of other types; and that if substantial support for competition triggers recurrence, this does not automatically imply that its absence fosters peace. In order to understand not only which types and combinations of democracy aid foster peaceful democratisation, but also which ones might cause violence to recur, I analyse their effect on both recurrence and non-recurrence of violence.

QCA starts from the assumption of maximum causal complexity. All theoretically possible combinations of the conditions are listed in the so-called truth table. Each row (namely, combination of conditions) represents a potential statement of sufficiency. Cases are assigned to the truth table rows that represent them best according to the empirical data, which then serves to calculate the degree to which a row can be considered sufficient for the outcome of interest. With the consistency threshold (which should be tailored to the data at hand, but at least 0.75) the researcher determines how much inconsistency is accepted for the rows to be included in the minimisation.Footnote 63 By discarding redundant information, algorithm-based minimisation reduces the truth table to its simplest, but still valid expression of sufficiency presented in the ‘solution’. I conduct fuzzy-set QCA using the Enhanced Standard Analysis and interpret the parsimonious solution after making sure that no untenable assumptionsFootnote 64 are included in the minimisation process.Footnote 65

The QCA identifies patterns – or alternative pathways characterised by a specific configuration of conditions – that explain the outcome under investigation. However, although such a configuration identified through the QCA suggests a causal relationship, it does not prove causation nor does it specify the causal mechanism that might explain the link between the pathway and the outcome. Therefore, I use qualitative insights to support the causal interpretation of the QCA results.Footnote 66 Even though a detailed process tracing to ascertain causality is beyond the scope of this article, insights from qualitative interviews thus help to conduct a plausibility check of the causal relationship suggested by the QCA.

Case selection

The analysis focuses on cases of (initial) democratisation in the aftermath of civil war in the period 1990–2014. Although supporting democratisation has been an integral part of international peacebuilding efforts since 1990, the argument that democratisation can trigger violent conflict is emphasised in particular for postconflict contexts. Thus, this article focuses on high-risk cases in which the destabilising effects of democratisation are presumably most pronounced. The end of the Cold War significantly changed the international system and international efforts to foster democracy in their current form only started thereafter. Focusing on all cases of civil war that ended in 1990 or later, the sample comprises 18 postconflict episodes that feature an increase in political competition shortly after the end of the civil war.

Civil wars are commonly understood as internal conflicts between the government and a non-state armed force aiming to overthrow the government or gain independence over a specific territory. Using data from UCDP/PRIO, this article applies the established threshold of one thousand battle-related deaths in one year to distinguish a civil war from (minor) civil conflict.Footnote 67 This yields a set of cases with a similar history of violent struggle and comparable legacy of violence shaping the dynamics of postconflict democratisation. Each postconflict episode constitutes a potential case. If a country has experienced several civil wars, each of these postconflict peace episodes is included as a distinct case, if it has been accompanied by democratisation.

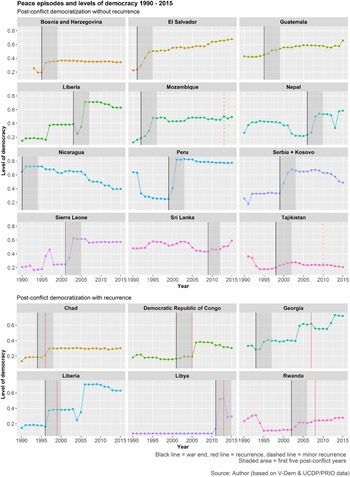

To determine if democratisation occurred after a civil war ended, I use the polyarchy index by the ‘Varieties of Democracy’ project dataset v. 7.1).Footnote 68 Designed to represent Dahl's concept of polyarchy, this narrow conceptualisation of democracy allows to clearly distinguish it from the outcome of interest, peace. Cases are considered ‘democratisers’ and become part of the sample if their level of democracy increases within the first five postconflict years. This selection explicitly includes cases whose initial increase in democracy levels was short-lived and followed by a deterioration within the five-year period.Footnote 69 Figure 1 displays all cases and their democratic trajectory between 1990 and 2015. The black line indicates the end of the war, the shaded area highlighting the five years after the war ended. A red line indicates a renewed outbreak of violence. A robustness test using the Unified Democracy Scores as an alternative measurement of democratisationFootnote 70 is presented in appendix 11. All 18 postconflict democratisers except Nicaragua start at very low levels of democracy and have been classified as closed or electoral autocracy at war's end by V-Dem in their ‘Regimes in the World’ indicator.Footnote 71

Figure 1. Case selection: Postconflict democratisers.

Outcome and periods of analysis

This analysis aims to explain when processes of postconflict democratisation remain peaceful. Peace is operationalised narrowly as the non-recurrence of violence until today, but at least for five years. Recurrent violence is captured in a fuzzy-set that differentiates between: (1) peaceful outcomes with no or minor violence below one hundred battle deaths; and (2) recurrence of major violence (above that threshold) up to full civil war. Each peace episode starts with the year after the civil war ended (that is battle deaths dropped below 25) and ends with the recurrence of major violence. Figure 1 presents all the cases clustered according to the outcome – whether they remained largely peaceful or experienced renewed violence. An alternative, qualitative assessment of peace serves for a robustness test, presented in appendix 11 (supplementary material).Footnote 72

The analysis includes the average support over the first seven postconflict years for each case; or as many years as peace lasted if recurrence occurred earlier. All cases have held formal elections within the seven-year period: Elections are key to arguments for both the positive effects of democracy, as well as its destructive forces, since they can act as a prism to set hidden potential for violence free.Footnote 73 Hence, this period ensures that each case had to pass this ‘test’ with its high risk of escalation.

Explanatory variables

This article focuses on support for: (1) competition; (2) institutional constraints; and (3) cooperation to analyse the effect of democracy aid on renewed violence in the context of postconflict democratisation. It further includes (4) a country's predisposition for conflict recurrence to capture the difficulty of the country context.

Per capita ODA commitments serve to approximate external support geared towards each area of engagement, using data provided by the AidData project (research release 3.0).Footnote 74 Since ODA is decided upon in bilateral negotiations, substantial commitments indicate that donors and recipient governments identified demand in the area and that donors know and care about developments, which can directly affect political dynamics. Although commitments reported by donors contain the uncertainty that the full amount might not have been disbursed, this article relies on commitments as the best available approximation for donor engagement in different areas: Only data on commitments provided by AidData after rigorous double-blind coding is accurate enough to allow a disaggregated analysis of democracy aid. Quality and coverage of available disbursement data is extremely limited.Footnote 75

The first condition captures substantial support for political competition. It includes the promotion of free and fair elections, the free flow of information, or strengthening pluralism directly by providing support for political parties, legislatures,Footnote 76 human rights, or civil society organisations. Second, substantial support for institutional constraints regards engagement in constitutional development, efforts to strengthen the capacity, accessibility, and independence of the judiciary and generally, the supremacy of the rule of law.Footnote 77 The third condition, substantial support for cooperation, is society focused. It measures support for dialogue, peaceful conflict resolution and reconciling different societal groups, including former conflict parties.Footnote 78 Since neither the OECD self-reporting system, nor AidData records this type of support separately, I use newly data coded in a joint research projectFootnote 79 (see appendix 4 in the supplementary material for more information).

I use fuzzy-set QCA to combine a qualitative differentiation in kind (for example, democracy vs non-democracy) with a quantitative differentiation in degree (for example, more or less democratic systems). The set-theoretic logic of QCA requires transforming raw data into meaningful sets. In contrast to crisp-set QCA that only offers a dichotomous distinction (1 or 0), using fuzzy-sets allows a more precise representation (between 0 and 1) of each case across the conditions. Assuming that not any negligible amount of external support matters, I define the crossover point (distinguishing between substantial and unsubstantial support) based on substantive and case knowledge combined with evident gaps in the data (see appendices 2 and 3 for a detailed elaboration). Appendix 11 presents various robustness tests performed of these calibration decisions. The three types of democracy aid are measured in per capita ODA commitments over the period of analysis.

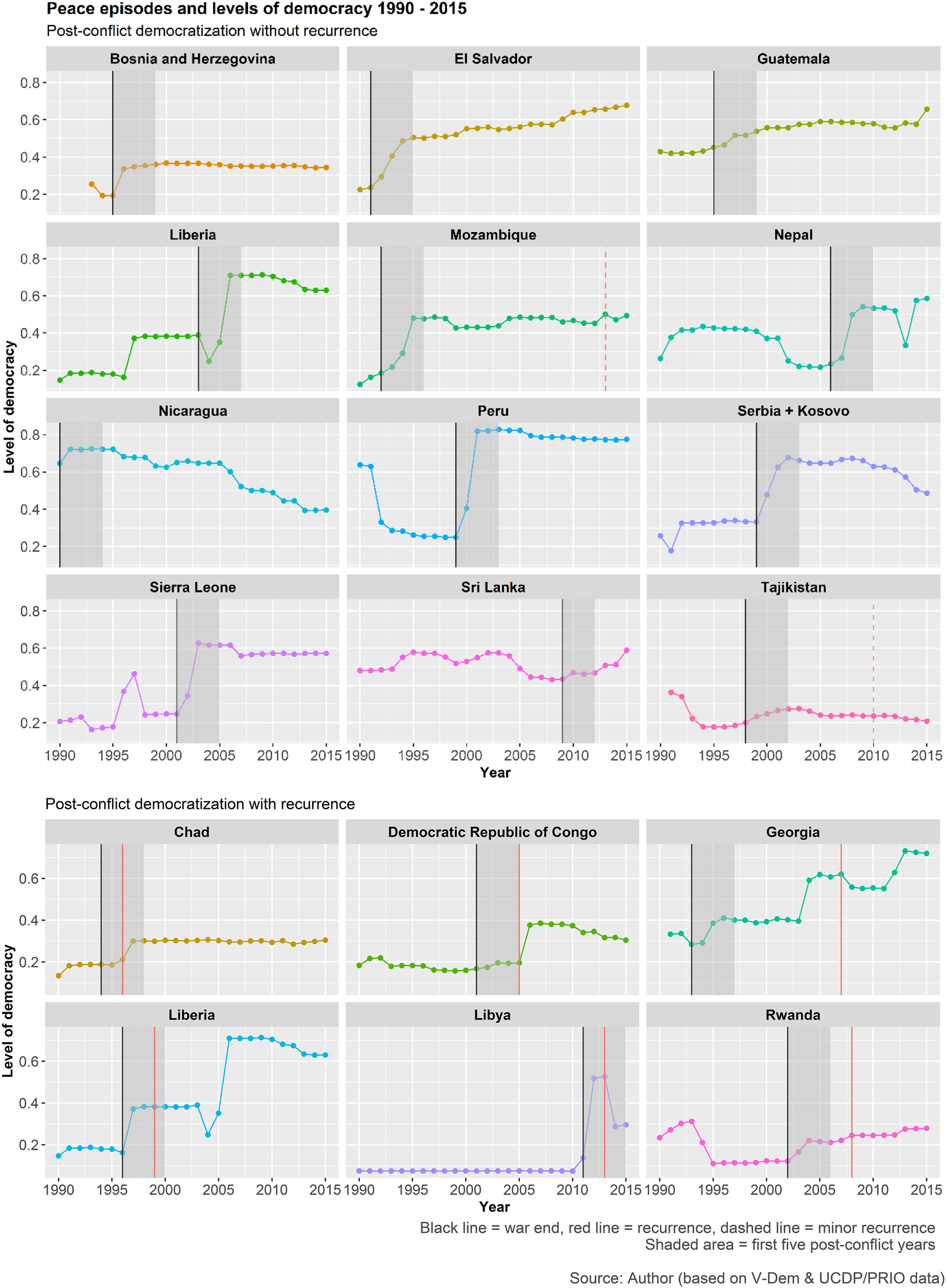

To take into account the contextual difficulty of building peace, the analysis includes a case's ‘predisposition for conflict recurrence’, that is, a particular high risk of renewed violence. Despite the possibilities of external actors to influence peace and democratisation, these processes are primarily domestically driven. If a case is highly predisposed to experience recurrence, the best external efforts might be insufficient to prevent a relapse. The aggregate condition ‘predisposition for conflict recurrence’ is composed of those factors established in the peace and conflict literature to increase the risk of recurrence. It assumes that characteristics of the previous war (short wars, less severe wars, and those with more than one faction involved), as well as structural context conditions (low socioeconomic development, high resource dependence and violent conflict in the neighbourhood) increase the risk.Footnote 80, Footnote 81 Appendix 5 provides a detailed overview of the operationalisation and calibration of this condition.Footnote 82 The empirical pattern shows that the predisposition does not drive support – neither are high predisposition cases more likely to receive support, not do external actors shy away from such contexts. Figure 2 depicts the distribution of the four conditions across the cases: Each bar shows the amount of ODA a case received over the period of analysis, the colours differentiating between the three types of support. The circle below each bar indicates whether the case has a high predisposition for recurrence (black) or not (empty circle).

Figure 2. Distributions of conditions.

Findings

This article uses fuzzy-set QCA to assess what combinations of democracy aid (support for competition, institutional constraints, and cooperation) can mitigate destabilising effects of postconflict democratisation. It identifies two combinations of support that can indeed help to sustain peace.Footnote 83 The strongest finding suggests that combining substantial support for competition with substantial support for institutional constraints can facilitate peaceful democratisation. Importantly, democracy aid is not associated with renewed violence.

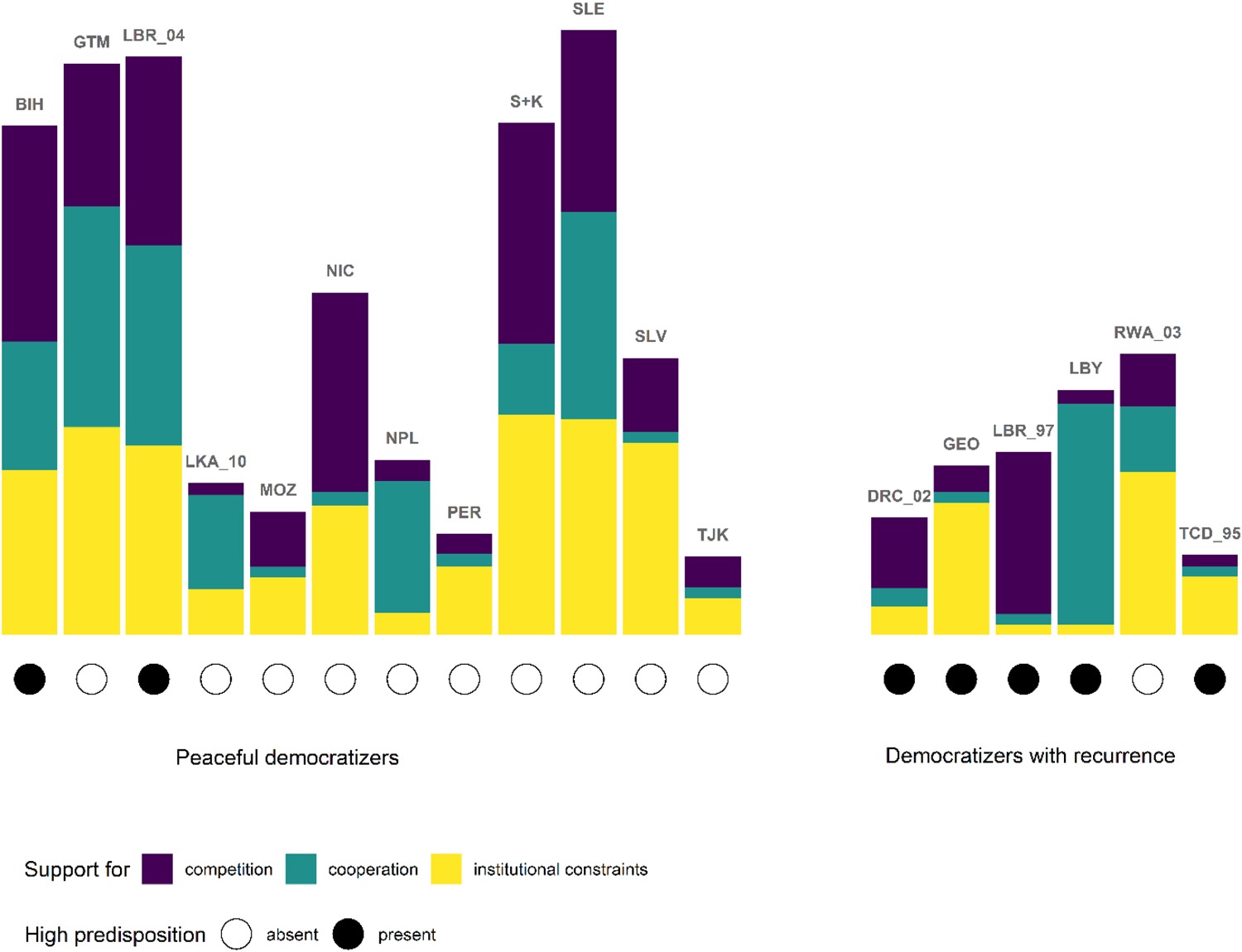

I conduct separate analyses for the presence and the absence of the outcome to gain a better understanding on whether certain aspects of democracy support can contribute to peace, or trigger renewed violence.Footnote 84 Table 1 presents the truth tables for peace and for recurrence, which is the first step in any QCA application. Based on the empirical data, the cases have been assigned to the truth table row – that is, combination of conditions – that represents them best. The consistency score (between 0 and 1) indicates the degree to which each combination of conditions can be considered sufficient for the outcome. A clear gap in the consistency levels of the truth table rows guides the placement of the raw consistency threshold at 0.77, determining which rows are consistent enough to be included in the subsequent minimisation process (Table 1).Footnote 85 Testing for necessary conditions yields no condition, or combination of conditions, that can be considered necessary for peace or recurrence (see appendix 9 in the supplementary material).Footnote 86

Table 1. Truth tables.

Note: A truth table does not present fuzzy-set scores but indicates the absence (0) and presence (1) of a condition.

(P) or (R) after the case names indicate if the case remained peaceful or experienced recurrence.

Peaceful democratisation

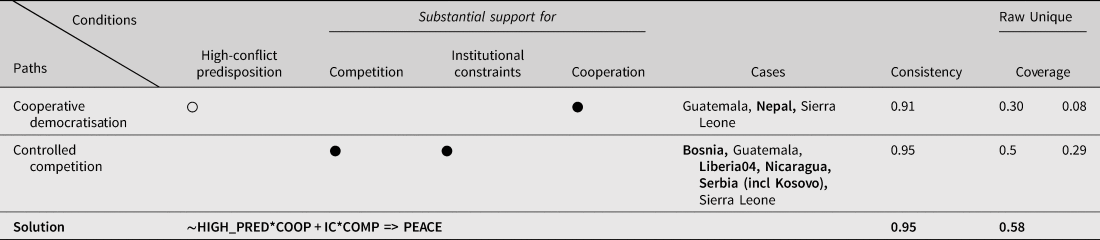

The analysis of sufficiency suggests two alternative pathways to peace during postconflict democratisation. The parsimonious solution explains seven out of the 12 cases that remained peaceful during democratisation after civil war. The consistency of 0.94 is sufficiently high to confidently warrant an interpretation of the results.Footnote 87

Table 2 presents the results. The first path ‘Cooperative democratisation’ shows that in cases without (empty circle) a high predisposition for recurrence, substantial support (filled circle) for cooperation alone can explain sustained peace. This path uniquely covers Nepal and includes Guatemala and Sierra Leone. It indicates the importance of external efforts to promote ‘cooperative democratisation’ by helping to bridge societal cleavages. In Nepal, a comprehensive peace agreement ended the civil war and abolished the monarchy, completely overhauling political power-relations. The comparatively low concentration of power and prewar democratic experience with long-established political parties could explain why societal reconciliation might be considered sufficient to foster peaceful democratisation in this case. However, since only one case is uniquely covered, it strongly drives this path, which must thus be interpreted with caution, as discussed further below.

Table 2. Peaceful democratisation (parsimonious solution).

Note: Empty circles depict a condition's absence (~), shaded circles its presence. Empty cells indicate that the condition does not help to explain the outcome; it can be either present or absent. Cases in bold are uniquely covered cases.

The second path ‘Controlled competition’ suggests that combined substantial support for institutional constraints and competition can facilitate peaceful democratisation after civil war, independent of the predisposition for conflict. Typical cases representing this path are, for example, Bosnia, Liberia since 2004 and Nicaragua. This path is highly consistent and explains half of all peaceful cases. Thus, supporting ‘controlled competition’ has a strong explanatory power. This is in line with the theoretical expectation that support for a competitive system needs to be accompanied by support for institutional constraints to prevent a monopolisation of power that would curtail pluralism. The two types of support apparently need to go hand in hand: On their own, neither can facilitate peaceful democratisation. Promoting ‘controlled competition’ by combining both types of support, however, can explain peaceful democratisation.

Guatemala and Sierra Leone are represented in both paths, that is, not uniquely covered. The two cases received all three types of democracy aid and did not have a high predisposition for recurrence – either of the two pathways could be at play, or even both at the same time. No contradictory cases are part of the solution – cases that according to the analysis would be expected to be peaceful but experienced renewed violence (deviant cases for consistency). Five peaceful cases are not explained by the solution (deviant cases for coverage): El Salvador, Mozambique, Peru, Sri Lanka (2010), and Tajikistan. This indicates that other factors might be necessary to explain this subset of cases, most of which experienced a particularly strong surge in democratisation after the civil war ended. They received no substantial democracy aid (Mozambique and Peru) or in one area only. These cases present interesting avenues for future research to further investigate what helped to facilitate peaceful democratisation in the absence of external support.

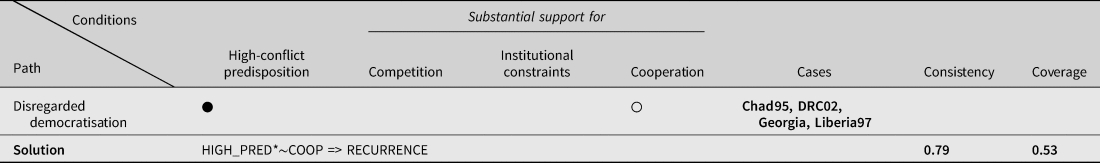

Democratisation with recurrence

Do specific kinds or combinations of democracy aid trigger renewed violence, instead of promoting peace? The analysis provides no evidence for a conflict-triggering effect of democracy aid. Testing for patterns that explain recurrence yields only one path in high predisposition cases: the absence of substantial support for cooperation (Table 3). The results indicate that a lack of democracy support explains recurrence in high risk cases, not its presence.

Table 3. Democratisation with recurrence (parsimonious solution).

Note: Empty circles depict a conditions absence (~), shaded circles its presence. Empty cells indicate that the condition does not help to explain the outcome, it can be either present or absent.

The consistency of the parsimonious solution for recurrence is too low for substantially interpreting the results. However, it supports the general picture – all pathways to peace contain the presence of democracy aid, while the path to recurrence is characterised by its absence. In light of concerns against democracy aid in postconflict contexts (based on the findings that democratisation can be destabilising (see Paris),Footnote 88 this adds strength to a general finding: The combined QCA results for peace and recurrence support that democracy aid can help prevent recurrence during postconflict democratisation. The findings do not suggest that such support inflicts renewed violence.

Discussion

The results hold against a wide range of robustness tests. Conducting robustness tests recommended as standards of good practice for QCA as well as more rigorous tests,Footnote 89 I perform five types of robustness tests by altering: (1) calibration and consistency thresholds; (2) case selection (including alternative measurement and operationalisation of democratisers); (3) operationalisation of the outcome (including an alternative, qualitative assessment); and (4) model specifications (that is, adding a condition capturing the overall amount of democracy aid or removing PRED). In addition, I engage in a modest form of (5) methodological triangulation by conducting a plausibility check with a qualitative case study. Overall, I conduct 52 alternative runs of the QCA across the different types of robustness checks (presented in appendix 11). All 52 tests except one yield solutions in sub- or superset relation to the main solution formula presented in the analysis, being in such a set-relationship is generally considered sufficient to increase the confidence in the results in QCA robustness tests. Both pathways are identified across almost all variations. However, as mentioned before, the first pathway (~PRED*COOP) only covers one case uniquely: Nepal. While small N research often relies strongly on individual cases, it is important to note that the path disappears when Nepal is removed and thus it needs to be interpreted with caution. Unusual for QCA, the vast majority of the tests (all except five), even yield the exact same solution formula as the standard model, with only minor variations in consistency and coverage. Thus, the QCA results can be considered highly robust.

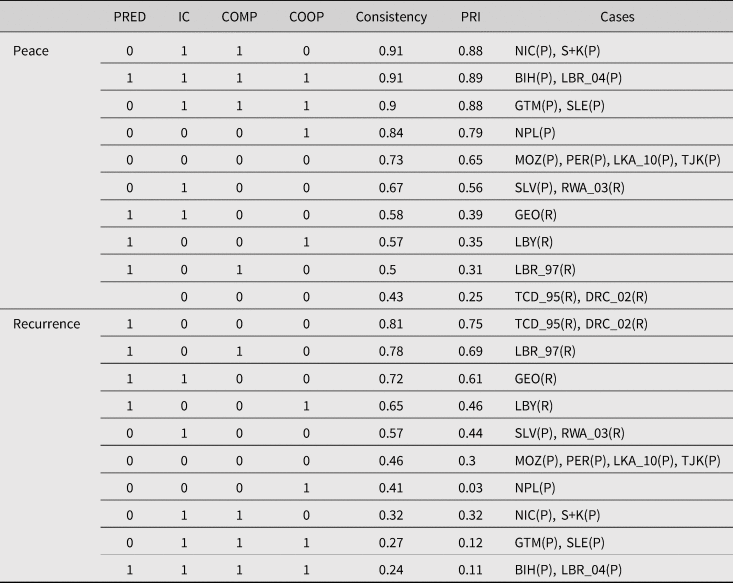

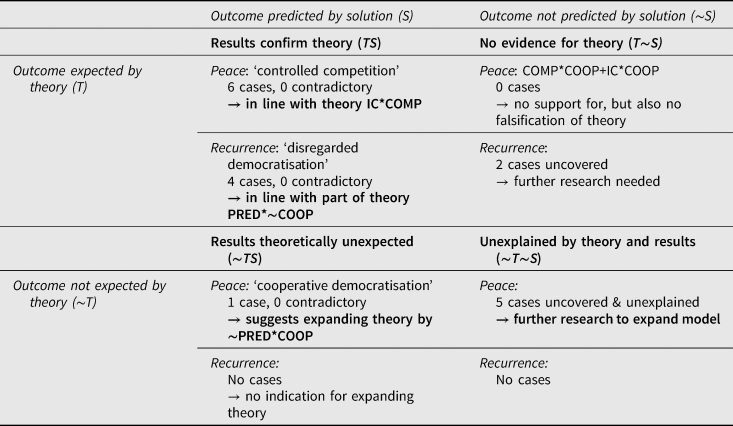

Comparing the theoretical expectations with the empirically observed pattern, QCA enables a formalised theory evaluation that helps to disclose (1) which parts of the theory are supported by the results; (2) in which direction theory should be expanded; and (3) which parts of theory should be discarded.Footnote 90 The results are summarised in Table 4 in a two-by-two matrix on whether the solution predicts the outcome or not, and whether it was theoretically expected, both for peace and for recurrence.

Table 4. Theory evaluation.

I theorised that combining substantial support for competition (COMP) with either substantial support for constitutional constraints (IC) or for cooperation (COOP) can mitigate destabilising effects of postconflict democratisation (COMP*IC + COMP*COOP + IC*COOP → PEACE). The path ‘controlled competition’ strongly supports the part of the theory stating that COMP and IC combined can facilitate peaceful democratisation. This finding is backed by six cases, which is one-third of all cases and half of the peaceful cases (TS, upper left quadrant). The path ‘cooperative democratisation’, was unexpected and may suggest a refinement of the theory (~TS, lower left quadrant). However, since it relies strongly on the Nepalese case (the only one uniquely covered by this path), the fact that it was also not backed by theory call for further restraint in its interpretation. As the table (left side) indicates, the solutions do not contain inconsistent cases (such cases would represent the configuration of conditions but not the outcome). Two theoretically expected pathways (COMP*COOP and IC*COOP) receive no empirical support (T~S, upper right quadrant). Since there was also no contradictory evidence, further research would be needed before discarding this part of the theory entirely. Five cases that have so far remained peaceful are neither explained by the theoretical model nor by the solution, indicating the potential existence of a yet uncovered, alternative pathway (~T~S, lower right quadrant). An in-depth, qualitative study could shed light on the factors that may explain this set of cases.

Regarding recurrence, the low consistency of the solution precludes drawing strong conclusions. Yet, the findings provide some indications. According to the theory, one type of support in absence of the other two types might contribute to renewed violence, which is not confirmed by the solution. Four cases support part of this expectation (TS): democratisation in the absence of democracy aid – more specifically ~COOP – explains renewed violence. Interestingly, two cases – Liberia_97 and Georgia – each represent the pattern PRED*COMP*~IC*~COOP and PRED*IC*~COMP*~COOP, thus receiving one type of support only (for competition and institutional constraints, respectively) in presence of a high predisposition. This provides further support for the argument that the two types of support need to be combined, as the solution for peace suggests. Two cases are not included in the solution, although their outcome was theoretically expected (T~S; Libya and Rwanda 03), both receiving one type of support only. There are no cases where the outcome was theoretically unexpected (~T).

Taking a closer look at the potential influencing factors discussed in the theory section provides some further insights (see appendix 6 in the supplementary material for an overview). All cases explained by the solution implemented a demobilisation process, which might indicate that this is a crucial accompanying factor, speaking to the findings by Dawn Brancati and Jack SnyderFootnote 91 on the importance of demobilisation before holding peaceful postconflict elections. However, it might also be the case that the international community engaged in these countries strongly pushed for and supported demobilisation processes. As Lilli Banholzer observes: ‘External actors are involved in almost every DDR intervention, playing either a supporting or a leadership role.’Footnote 92 Interestingly, two cases that remained peaceful but are not explained by the solution did not demobilise the warring parties. Other contextual factors present no clear picture: V-Dem data on the level of democracy at the end of the war and the concentration of power varies substantively across these cases and does not provide a clear pattern. Three of the five peaceful cases that are not explained by the solution have a comparatively high level of GDP per capita, speaking to the literature identifying a high level of socioeconomic development as a facilitating factor for democratisation and as reducing the risk of civil war recurrence. This favourable context might thus explain why these countries managed peaceful democratisation without international support.

Liberia: A plausibility probe

To assess the plausibility of the causal relationship suggested by the QCA, Liberia serves as an illustrative case study of the path ‘controlled competition’. This path explains the majority of peaceful cases independent of their predisposition. As a typical, uniquely covered case in this path, Liberia is well suited for conducting a plausibility probe.Footnote 93 Moreover, with a high predisposition for conflict Liberia represents a particularly difficult case. Drawing on forty qualitative interviews and secondary sources, I examine in what way the combined substantial support for competition and institutional constraints has helped to prevent destabilising effects of postconflict democratisation. The plausibility of support for ‘controlled competition’ is confirmed in Liberia by (1) comparing the first and second postwar period and (2) tracing the combined effect of these two aspects of democracy aid.

After the first civil war, donors provided substantial support for competition to facilitate democratic elections in 1997.Footnote 94 Yet, support for strengthening institutional constraints was neglected. Although the elections were fairly well organised thanks to international support, the electorate did not believe that warlord Charles Taylor would accept defeat, nor that he could be prevented from resorting to violence in that case.Footnote 95 Yet, he was also able to draw on his superior resources and networks for his landslide victory with the infamous slogan ‘He killed my ma, he killed my pa, I'll still vote for him.’ The elections were followed by a short period of stability. Yet, soon Taylor used his democratically legitimated power to establish control over the media and crack down on the opposition. The emerging democratic institutions were too weak to provide any effective checks on his abuses of power.Footnote 96 In 1999, fighting resumed and newly formed armed groups challenged Taylor's power violently.

After the second civil war ended in 2003, donors provided substantial support both for competition and for institutional constraints, which helped to render democratisation peaceful. The risk that democratisation might trigger renewed violence was still considerable: The high concentration of power in the centralised presidential system yields high stakes in the elections, inflammatory rhetoric was used in all three rounds conducted since 2003, and after each presidential election the losing party did not easily accept defeat.Footnote 97

All interviewees agreed that international support for the elections substantially enhanced the quality and credibility of electoral procedures and results, which was important to prevent renewed violence. ‘We did not have the capacity in 2005 to organize a credible election. We could have organized an election [in 2005], but the extent of legitimacy of this election was questionable without international support. We needed [the reassurance] that “this election is independent, it's free and fair, it's organized by the United Nations”’ (Interview 4_20-11-2017).Footnote 98 Several interviewees emphasised that (only) defective and incredible elections would contain the risk of violence in Liberia and that the substantial external support especially in 2005 and 2011 lent the results crucial legitimacy. As interviewees stressed, in 2011 the losing party had difficulties accepting the results, but ‘they did not have any evidence to show that they were cheated. Because the process was managed by the international community’ (Interview 33_04-12-2017, also 28_30-11-2017). The international support reduced the basis for allegations of fraud, and rendered violent mobilisation less likely, preventing a violent escalation.

Furthermore, interviewees underlined the importance of civic education and freedom of speech for democratic development in Liberia and acknowledged that international support played a major role, for example by pushing for a law on the freedom of speech. This allows grievances to be publicly raised without adhering to violence: ‘People are able to express themselves freely without being penalized or without being put in jail. So freedom of expression is there which [allows] for people to vent out their anger and talk about things instead of being suppressed and then they find a way out’ (Interview 37_04-12-2017, see also 4_20-11-2017, 24_29-11-2017). Thus, international support for competition prevented renewed instability caused by weak and defective democratic procedures unable to provide a sufficient degree of impartiality, transparency, and credibility.

In addition to support for competition, substantial support was provided for strengthening institutional constraints after 2003. While the judiciary still faces serious deficiencies, international efforts have helped to enhance its capacity and independence, and generally strengthen the rule of law. ‘There was lots of support to reforming the justice system. We have more courts; our courts are now functional. Even if we still have challenges with prolonged detention, pre-trial detainees - people are now taking action to the court rather than taking the law in their hands’ (Interview 8_21-11-2017). In contrast, ‘in the past, those who did not go to the court at that time felt that that was a waste of time, that they would not get justice’ (Interview 12_23-11-2017). Moreover, various ‘integrity institutions’ have been established with strong international support, including an auditing, human rights and anti-corruption commission. Thus, international support was crucial to establish certain checks on the executive (even if these are still limited), restraining the ability of the ruling party to silence critical voices or engage in overt rent-seeking (Interviews 11_22-11-2017, 10_22-11-2017, and 4_20-11-2017).

The combined support for competition and institutional constraints helped to render postconflict democratisation peaceful in Liberia: facilitating fairly competitive and credible elections reduced grounds for challenging the results violently by preventing grievances caused by an uneven playing field, substantial procedural deficiencies or deliberate fraud. The increased credibility and legitimacy of the results not only minimised legitimate reasons to challenge the results but also curtailed the potential of a sore loser to mobilise violent protest. However, the allegations of fraud as well as fears that the situation might escalate, demonstrate that the support for competition by itself was not sufficient to facilitate an electoral process without grounds for contestation. In that context, it was important that the judiciary had been sufficiently strengthened to provide a credible, peaceful alternative to challenge the results (Interviews 12_23-11-2017, 20_28-11-2017, 8_21-11-2017). For this, the 2017 presidential elections provided an illustrative test case. After the first round, the second-placed party filed an official complaint, upon which the electoral commission halted the process to investigate. The commission, and later the Supreme Court took the complaint seriously, but eventually dismissed the allegations. All political parties patiently awaited and accepted the ruling, facilitating the first peaceful handover of power since 1944. Observers emphasised it as a significant achievement that instead of protesting violently: ‘People are turning to the law, people are having some level of faith … instead of saying we fight’, which has been achieved with international support for reforming the judiciary (Interview 4_20-11-2017). However, the allegations of fraud demonstrate that the support for competition by itself was not sufficient to facilitate an electoral process whose results would be beyond doubt and without grounds for contestation. Therefore, it was important that the judiciary had been sufficiently strengthened to provide a credible, peaceful alternative to challenge the results, whose verdict was patiently awaited and accepted by all parties.

Apart from democracy aid, other factors also played a role. In 1997, an UN observer mission and regional peacekeeping forces were present, yet left soon after the elections. In contrast, the robust UN peacekeeping mission after 2003 was not only much stronger but also stayed for an extended period, which helped to address the credible commitment problem and provided time for institutional development.Footnote 99 However, as Virginia P. Fortna argues in her seminal book, the effect of peacekeeping works not only through military means, but also by influencing political dynamics through facilitating communication or providing support for elections and human rights.Footnote 100 In fact, an UNMIL representative describes governance and anti-corruption as key priorities in the immediate postconflict phase (Interview 6_20-11-2017). These types of activities, however, clearly constitute democracy aid and as such are included in the analysis.

Another key difference compared to 1997 was the absence of most former fighters – member of the transitional government were prohibited from running for presidency – from the 2005 presidential elections, though not from other elections. Most importantly Taylor was excluded due to his exile and later imprisonment. Yet, beyond the 2005 presidential elections, former wartime leaders have largely been co-opted into the political system, which seems to has worked as an effective alternative to deal with spoilers.Footnote 101 The former warlord Prince Johnson was one of the main contenders in the 2017 elections.

These factors also indicate that in situations where domestic institutions cannot yet credibly constrain potential spoilers, external enforcement can serve as a substitute. While indictment before the criminal court is a very exceptional, extreme example, research shows that lower-scale international scrutiny such as international peacekeeping, but also donor engagement or electoral observation missions can already make a difference in providing constraints on political actors.Footnote 102 When Taylor won the elections in 1997, he was able to act as he did because no domestic or international enforcement mechanisms existed that could impose the provisions entailed in the peace agreement.Footnote 103 In 2005, the strong international engagement was able to serve as ‘a neutralizing force for everybody in the system’ (Interview 15_24-11-2017).

Conclusion

Can democracy aid tame postconflict democratisation processes? The relationship between peace and democratisation has been a topic of debate for decades. This matters particularly for countries just emerging from civil war: On the one hand, (functioning) democratic institutions are supposed to provide mechanisms of conflict management that can help to facilitate peaceful cohabitation after civil war. On the other hand, the postwar context appears to be particularly unsuited to handle certain aspects of transition towards liberal democracy. This article contributes to the debate by taking a disaggregate perspective on the role democracy aid can play in this context. It theorises and empirically investigates what kind of external support targeting key dynamics of postconflict democratisation (that are either peace-enhancing or peace-threatening) can mitigate potential destabilising effects, or, alternatively, might trigger renewed violence. A case's predisposition for recurrence is factored in to account for difficult contexts.

Using fuzzy-set QCA to analyse patterns of democracy aid that explain sustained peace during postconflict democratisation, this article identifies two robust pathways to peace: (1) substantial support for cooperation in the absence of a high predisposition; and (2) substantial support for institutional constraints provided jointly with support for competition, independent of the predisposition for conflict recurrence. A qualitative case study of the second path ‘Controlled competition’ confirms the plausibility of the results drawing on the Liberian case. These empirical findings speak well to the theoretical expectations. Supporting meaningful competition is important, yet on its own insufficient to sustain peace. The same holds for support for institutional constraints. Only in combination, the QCA indicates, can these two types of support facilitate peaceful democratisation after civil war. However, the theoretical expectation that support for competition alone might trigger renewed violence has not been confirmed.

Thus, more generally, the analysis soothes concerns by scholars and practitioners that postconflict democracy aid causes instability – the results do not indicate that any of these aspects of democracy aid is linked to recurrence during postconflict democratisation. Instead, they suggest that specific combinations of democracy aid can indeed help to sustain peace in this context. The analysis focuses on democratisation after civil war, which according to the literature constitutes ‘least likely contexts’ of peaceful democratisation. Therefore, it is plausible that the findings also apply to processes of democratisation more generally, but need to be confirmed by additional research. Further avenues for research emerge: to explore those cases that democratised peacefully without international support, investigate the role specific institutions and their quality play, as well as other context conditions, such as previous democratic experience, economic inequality or power-sharing.

Moving beyond the question of whether democratisation helps or hampers building peace after civil war, this study adds to the debate by providing new insights on the circumstances under which postconflict democratisation contributes to peace, namely when accompanied by democracy aid. The findings speak to previous research that investigates which factors render democratisation and postconflict elections less prone to violent conflict.Footnote 104 This article is the first to disaggregate democracy aid and analyse its effect on conflict recurrence. Using a configurational approach presented new and nuanced insights, shedding lights on the specific combinations of democracy aid that help to foster peaceful democratisation after civil war, which can provide guidance to policymakers designing postconflict support strategies.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to Carsten Schneider and Adrian Dusa, as well as colleagues from the German Development Institute and the University of St Gallen, participants at various conferences, and the anonymous reviewers for helpful feedback at different stages. My special thanks go to Charlotte Fiedler, Sebastian Ziaja, and particularly Tina Freyburg for their in-depth engagement with my work. I warmly thank the interviewees in Liberia for generously sharing their invaluable insights.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit: {https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2021.36}

Karina Mross (PhD, University of St Gallen, 2019) is a researcher at the German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik. Her research focuses on democratisation, peace, and social cohesion after civil wars, as well as international democracy promotion and peacebuilding efforts in postconflict societies.