INTRODUCTION

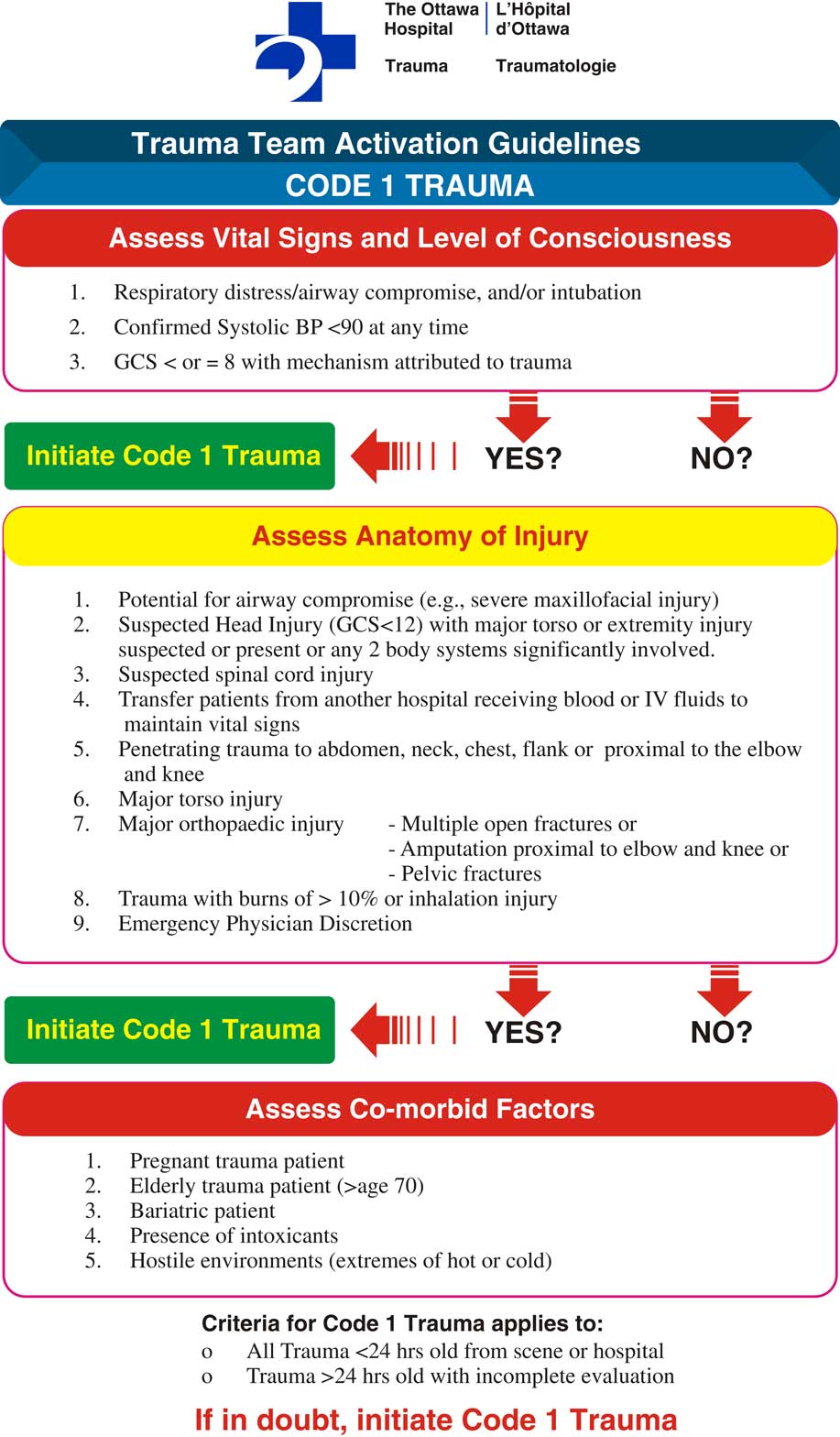

Injury is a major source of morbidity and accounts for 9% of global mortality. 1 It is the leading cause of death for young people in Canada ages 1 to 34 2 years and also an important cause of hospitalization, impairment, and disability throughout all age groups, including seniors. 3 Patient care at dedicated trauma centres has been shown to both lower mortality and improve functional outcomes in trauma patients.Reference Nirula and Brasel 4 , Reference Celso, Tepas and Langland-Orban 5 Trauma teams are multidisciplinary and made up of emergency medicine physicians, anesthetists, general surgeons, nurses, and other support staff led by a team leader. The aim of this team is to rapidly assess and stabilize the trauma patient and arrange definitive treatment. Trauma code activation is most frequently initiated by emergency physicians using physiological and anatomical criteria, mechanism of injury, and patient demographic factors, in conjunction with data obtained from emergency medical service personnel. Specific criteria for activation at our institution can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The Ottawa Hospital Trauma Team Activation Guidelines.

Having a dedicated trauma team composed of emergency physicians and trauma surgeons has been shown to improve mortality among severely injured trauma patients.Reference Gerardo, Glickman and Vaslef 6 Delayed activation of the trauma team has been shown previously to be a common provider-related complication in evaluating trauma service performance.Reference Hoyt, Hollingsworth-Fridlund and Winchell 7 Delayed trauma team activations at a Level II trauma centre in the United States were significantly linked to patients over age 55, non-white ethnicity, blunt force assault, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 15, Injury Severity Score (ISS) of 16 or higher, and head injury with maximum Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) of 3 or higher. In this study, they found no link with increased mortality for delayed trauma team activation but did find that hospital length of stay was longer, and discharge to a rehabilitation facility was more common.Reference Ryb, Cooper and Waak 8 There has been no study looking at delayed trauma team activation in the Canadian setting. Our goal was to identify factors that may be associated with delayed activation in our setting to inform our trauma team activation policy.

Our study assessed delays in trauma code activation in the setting of a Canadian Level I trauma centre. Our objectives were to 1) analyse factors associated with delayed activation of the trauma team to help characterize the patient populations who are at risk for potential poor outcomes in trauma and 2) determine patient outcomes between those who had no delay versus those who had a delay in trauma code activation.

METHODS

We conducted an ethics review board-approved health records review to augment data already collected as part of a regional trauma data repository. Our tertiary care regional trauma centre serves a population of 1.23 million people over a 17,000 square-kilometer area with an annual patient census of more than 70,000. 9 Our centre is a regional adult referral centre that receives referrals from 13 hospitals within a regional trauma network as well as occasionally from hospitals outside of our trauma network. A trauma bypass procedure exists for paramedics to divert directly to our trauma centre instead of the nearest hospital in our network when appropriate. Trauma patients at our centre, if requiring admission, would be admitted under the care of a trauma surgeon to a dedicated trauma unit or to an intensive care unit, if they had more immediate life-threatening injuries. When a trauma patient is seen in the emergency department (ED), he or she is assessed by the emergency physician who makes a decision to activate the trauma team, which activates a multidisciplinary team, including a trauma team leader as well as early X-ray and computed tomography (CT) imaging.

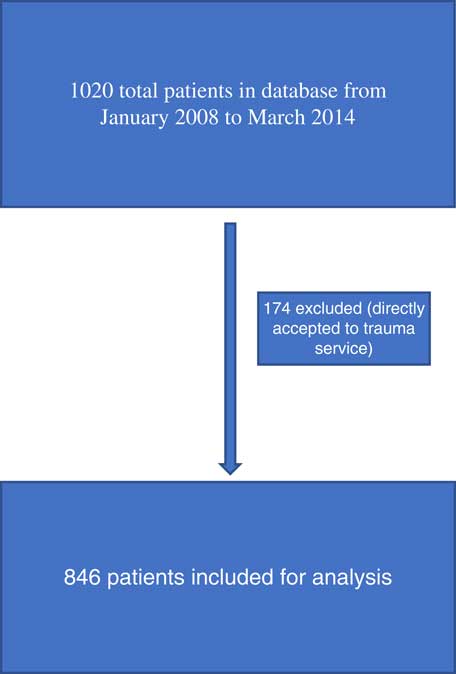

Consecutive trauma cases from January 2008 to March 2014 were selected for review. As seen in Figure 2, we included any trauma code activation by an emergency physician. Trauma code activations that were accepted directly to the trauma service prior to arrival to the ED were excluded. These patients would have had the trauma team activated automatically upon patient arrival prior to emergency physician assessment and were managed differently with the emergency physician not involved in the decision to activate the trauma team. These two patient populations would differ in acuity and time from injury, and, for this study, we were looking specifically at the decision-making of the emergency physician to activate the team or not. Based upon a prior study looking at delay in trauma team activation, we defined delay in trauma code activation as a time greater than 30 minutes from the time of arrival in the ED to the activation of the trauma team.Reference Ryb, Cooper and Waak 8

Figure 2 Summary of patients included for analysis.

A single reviewer identified cases meeting the inclusion criteria from data already available in a trauma database maintained by a data analyst. A standardized data extraction form was completed, including age, sex, mechanism of injury, ISS, history of ethanol use, time from injury, and time of presentation. We looked at whether patients were transferred via ground or air ambulance. The ground ambulance crews consisted of both primary care paramedics and advanced care paramedics who have additional training and scope of practice above primary care paramedics. For example, advanced care paramedics would be trained in endotracheal intubation, compared to primary care paramedics, who would be limited to supraglottic airways. Air ambulance crews included critical care paramedics who have a greatly expanded scope of practice above advanced care paramedics, such as rapid sequence induction intubation. Some of the emergency physicians also work as trauma team leaders at our centre, although not while they are staffing the ED. We looked at this variable and the emergency physicians’ experience, whether they had been involved in more than 10 codes over the study period. We also looked at patient arrival by time of day. Comparison of severity of injury between the two groups was done using the AIS (1-6) and ISS. AIS 1-6 are based on the following regions: head and neck, face, chest, abdomen, extremities, and external injuries. From the AIS scores, a total ISS is calculated, which is a standardized measure of injury severity.Reference Baker, O’Neill and Haddon 10 All data from codes, which were identified as delayed, were checked manually via chart review, and any missing data from the trauma repository were extracted via chart review for those cases. In cases of discrepancy between data from the chart and the database, the chart data were used. For two datapoints in the database, there were substantial missing data, including 32.3% did not have any data on blood alcohol level, and 23.6% of patients did not have a time of injury.

Data were collected on a Microsoft Excel sheet and exported into the Statistical Analysis System (SAS). A univariate analysis was performed to look at factors that may influence trauma team activations. We subsequently used multiple regression analysis models for delayed activation in relation to discharge destination, mortality, length of stay, and time to operative management.

RESULTS

From 1,020 patients identified by the trauma database, 174 patients were excluded because they were seen directly by the trauma team, leaving 846 patients for analysis. Table 1 summarizes the baseline patient characteristics. The mean age was 41.2 years old with 77.4% being male. The mean ISS score was 21.8. The mechanism of injury in the majority of patients was from blunt trauma (74.0%) followed by penetrating injuries (25.5%). Most patients were transferred to the hospital by ground ambulance (88.7%), with 9.5% via air ambulance; 1.9% of patients were walk-in arrivals and not via ambulance, and 14.7% were transferred from another hospital for assessment by an emergency physician. These patients were not accepted directly to the trauma team; 23.5% of all patients had an ethanol level measured above the Canadian legal limit for operating a motor vehicle, although a large proportion (32.3%) was not tested.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of trauma patients (N=846)

ED=emergency department; EMS=emergency medical services; EP=emergency physician; TTL=trauma team leader.

* Blood alcohol legal limit in Canada=17 mmol/L.

Table 2 shows the outcome data for all patients in the study; 5.8% of these patients died in the ED, and 85.0% survived to discharge; 41.5% of all patients were discharged home, 16.3% were sent to a specialized rehabilitation facility, and 2.2% percent were sent to other discharge destinations, which consisted mainly of local homeless shelters and group homes.

Table 2 Outcome characteristics of trauma patients (N=846)

ED=emergency department.

* Other destinations included local homeless shelters, nursing homes, and unknown.

A comparison between early and delayed activation of the trauma team can be seen in Table 3. In trauma codes, 4.1% (35/846) were activated after 30 minutes. The median length of time from arrival to activation of the trauma team was 5 minutes in the early group versus 41 minutes in the delayed group (p<0.01). Mean ISS scores were very similar between the two groups as well as component AIS scores and physiological data. Delayed trauma activation was more frequent in older patients. Mean age was significantly different between the two groups at 40.8 years in the early group versus 49.2 in the delayed group (p=0.01). Age over 55 years was also statistically significant (22.4% in the early group v. 37.1% in the delayed group; p=0.04). Age over 70 years was statistically significant (7.6% in the early group v. 17.1% in the delayed group; p=0.04). There was no statistical difference in terms of what time of day that the patient arrived in the ED. There was a higher percentage of blunt trauma in the delayed group (85.7% v. 73.5%), but this did not approach statistical significance (p=0.3). Emergency physician level of experience was similar between the early and delayed groups.

Table 3 Comparison of early versus delayed activation of trauma team

AIS=Abbreviated Injury Scale; BP=blood pressure; bpm=beats per minute.

As seen in Table 4, there was no significant difference in mortality. Survival to discharge was 84.8% in the early group versus 88.6% in the delayed group (p=0.54). Median length of stay was identical at 10 days in both groups. Median time from arrival in the ED to operative management was similar (331.0 minutes in the early group v. 277.5 minutes in the delayed group; p=0.52). There was no significant difference in terms of hospital discharge destination or destination from the ED.

Table 4 Outcome data comparing early versus late activation of trauma team

DISCUSSION

Our data, in the setting of a Canadian Level I trauma centre, showed that approximately 4% of trauma team activation occurs after 30 minutes. The only clear association was age, in terms of risk factors for delayed activation. There was no difference in terms of outcome data such as mortality, hospital length of stay, or time to operative management. The two groups were similar in terms of their severity of injuries. Elderly trauma patients are recognized by trauma guidelines to be at risk for more adverse outcomes post-injury,Reference Calland, Ingraham and Martin 11 and age over 70 years is included in the trauma activation guidelines at our institution (see Figure 1). Age over 70 years has also been postulated to be a cut-off for increased mortality in elderly trauma patients.Reference Caterino, Valasek and Werman 12 Elderly patients may not mount the same physiological response to trauma as younger patients do to both age and medications, such as beta blockers, and therefore their vital signs may be falsely reassuring. In general, the small percentage of delayed activation and the lack of any differences in outcome likely mean that the activation system is working efficiently. However, it appears that, despite data and guidelines stating that elderly patients are at high risk of poor outcomes, they are still at risk for under-triage, and further emphasis on having a low threshold for trauma activation in the elderly would be appropriate.

To our knowledge, this is the only Canadian study looking at delayed trauma team activation. Ryb et al. undertook a similar study looking at trauma team activation at their Level II trauma centre in Maryland (United States).Reference Ryb, Cooper and Waak 8 Similar to the Ryb et al. study, we found mean age to be statistically significant. Unlike their study, we did not find blunt trauma, a higher ISS, or head injury as significant causes of delayed activation of the trauma team. As seen in their study, there were no differences in patient outcomes. Our population of trauma patients was substantially sicker, and it would seem that we have a much higher threshold to activate the trauma team. Our mean ISS was 21.8, which was substantially higher than seen in the Ryb et al. study, which had a median ISS in their delayed activation group of 9 and 5 in their early activation group. Our median length of stay was also much higher (10 v. 1-2 days). This likely represents a difference in practice between the two centres of when to activate the trauma team.

Another study in Maryland (United States)Reference Chang, Bass and Cornwell 13 has shown that patients over the age of 70 years were less likely to be transported to trauma centres, despite meeting criteria, and attributed this to an unconscious age bias. It is possible that this unconscious bias is what contributed to the increase in age in the delayed population in our study.

Some of the limitations of this study include that it is retrospective and, as such, prone to all of the limitations of retrospective studies. Given that this was a local study of one trauma system, it may not be generalizable to other trauma systems. It was not practical to go through each case in the early activation group to see whether the cases met trauma code activation criteria, mainly due to lack of clear charting around decisions to activate the team. The exact criteria for activation for each case in the delayed group were not clear; therefore, the reason for delays remain unclear. This is likely multifactorial and, given the increased age in the delayed group, represents an unconscious bias to either under-triage or delay activation of the trauma team in elderly patients. There were also data that were incompletely captured, and it is possible there were cases that were missed entirely in the trauma database, because each case was put in manually by a research assistant, which could bias our results. We tried to mitigate this by using a large sample size over several years and looking at the delayed codes in further detail. It was not possible to assess cases that were never called as trauma codes but met activation guidelines. Importantly, given the relatively small number of delayed activation, this study may be underpowered to see differences in outcome data, including morbidity and mortality.

CONCLUSION

Our trauma activation guidelines appear to result in very few delayed activations of the trauma team. Trauma team activation delays were not associated with worse outcomes in our population. Delayed activation is linked with increasing age. Considering there were severe injuries in this delayed cohort that required activation of the trauma team, this suggests that further emphasis and intervention on the aging trauma patient should be made to recognize this vulnerable population. This is especially important given an increasingly aging population that will likely result in a larger percentage of geriatric trauma in the future.

Competing interests: None declared.