Between 1910 and 1920, forty U.S. states created mothers’ pension programs, giving needy “deserving” mothers, typically widows, cash aid to support their dependent children. The primary goal of the grants was to enable poor mothers to raise their children in their own homes rather than surrender them to orphanages or foster care. A secondary goal, less recognized today but often invoked by Progressive Era social welfare reformers, was to reduce child labor. While existing research shows that child labor laws largely failed to significantly reduce children’s workforce participation, we examine whether policies that tackled the problem by providing aid – rather than by penalizing work – were more effective.

The short answer is that they were not. States and counties with more generous mothers’ pension programs did not see greater declines in population-level child labor rates than those with a less generous, or no, program. This is somewhat surprising because prior research on mothers’ pensions as well as on contemporary cash transfer programs shows benefits. Mothers’ pensions increased educational attainment and longevity among children who received them in the early twentieth century (Aizer et al. Reference Aizer, Eli, Ferrie and Lleras-Muney2016). Similarly, contemporary conditional cash transfer programs in developing countries increase school enrollment and reduce child labor (Skoufias and Parker Reference Skoufias and Parker2001; Schultz Reference Schulz2004; Edmonds Reference Edmonds2007; Baird et al. Reference Baird, McIntosh and Özler2010; Baird et al. Reference Baird, Ferreira, Özler and Woolcock2014; Benhassine et al. Reference Benhassine, Florencia Devoto, Dupas and Pouliquen2015). We provide evidence that pensions suffered from limited generosity and coverage, as well as a lack of conditionality, and surmise that these weaknesses may account for pensions’ failure to reduce child labor at the population level. Another potential explanation stems from states’ and counties’ limited administrative capacity to monitor recipients and ensure that eligibility criteria, such as regular school attendance, were being met.

Were child labor laws effective? Mixed evidence from 19th- and 20th-century U.S. and U.K.

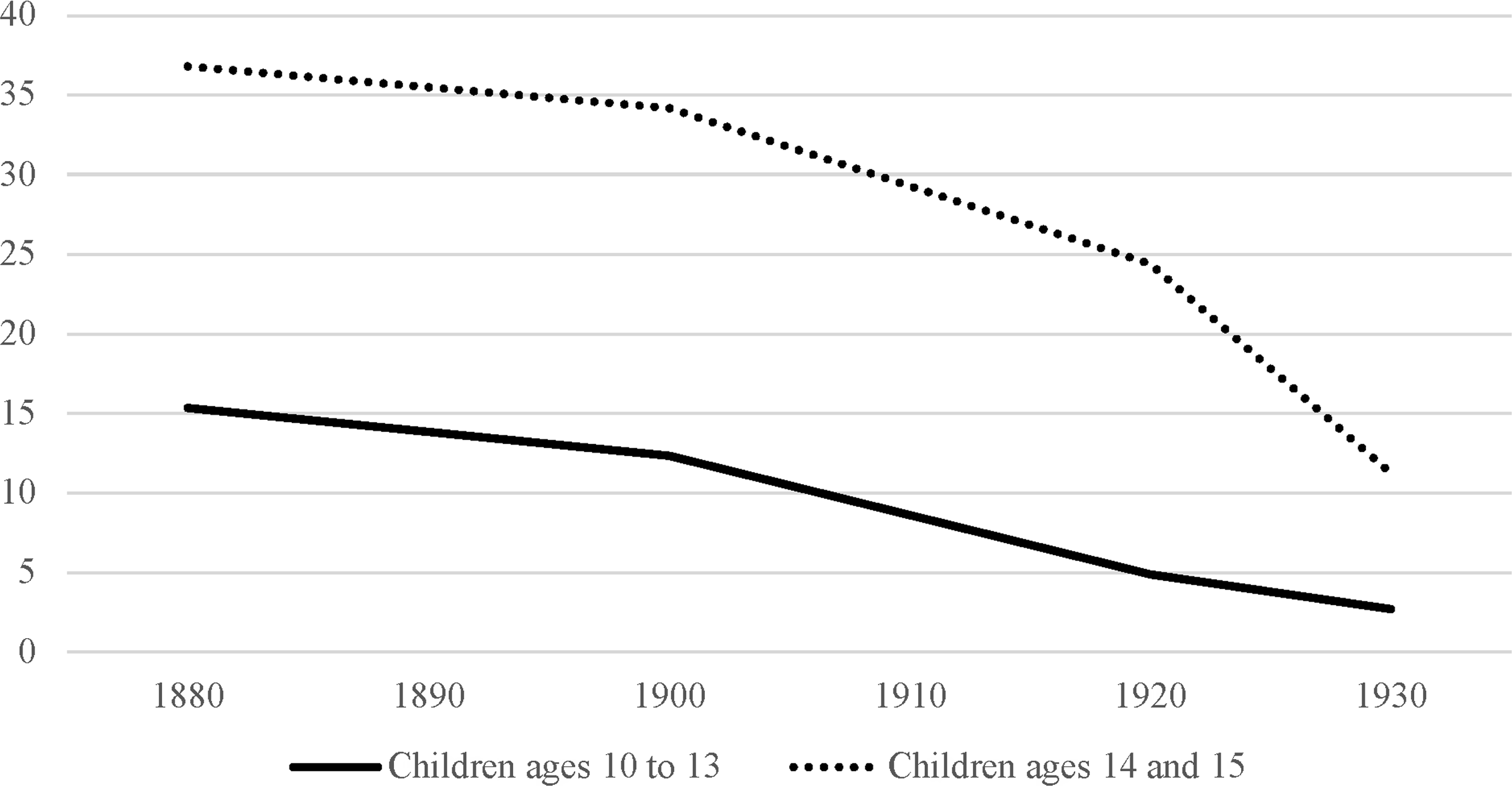

Labor force participation among 10- to 13-year-olds decreased sharply between 1880 and 1930 in the U.S., from roughly 16 percent of children working to only about 3 percent. Labor also declined sharply among children age 14 and 15, from about 37 to 11 percent of children working (see Figure 1). Most of the decline occurred in agriculture – a sector whose share of the overall U.S. workforce went down by more than half during this period (Lebergott Reference Lebergott and Brady1966) – but child labor decreased significantly in manufacturing and other employment sectors, as well. The Census Bureau reported that between 1910 and 1920, the decade when the majority of mothers’ pension programs were adopted, the number of children engaged in agricultural pursuits declined by 54.8 percent, while the number of children employed in non-agricultural pursuits declined by 25.9 percent (US Bureau of the Census 1924: 11).Footnote 1

Figure 1. Decline in labor force participation among U.S. children aged 10 to 15, 1880–1930, all industries.

The dramatic decrease in children’s workforce participation has prompted economic historians to ask whether any of the decline, particularly in the regulated manufacturing sector, can be attributed to child labor laws. By 1910, 43 states had enacted laws establishing minimum working ages and maximum working hours for children in manufacturing and usually also mining. In 1915, the modal minimum legal working age was fourteen (Lleras-Mooney Reference Lleras-Mooney2002: 410). However, research suggests that these regulations had limited impact on child labor.

For example, Moehling (Reference Moehling1999) compares the difference in occupation rates of thirteen- and fourteen-year-olds in states with a minimum manufacturing employment age of fourteen versus states without such a restriction. In addition, for those states with minimum age rules in place, she compares differences in thirteen- and fourteen-year-olds’ occupation rates before and after the rule was enacted. Moehling concludes that very little, if any, of the decline in child labor in the U.S. between 1880 and 1930 can be attributed to state child labor laws. Similarly, Nardinelli (Reference Nardinelli1980) concludes that the British Factory Acts of the mid-nineteenth century, which established working age minimums and hours maximums for children in textile mills, at most sped up a process that was already underway, namely the replacement of child workers by adult women and labor-saving technology.

Basu (Reference Basu1999) argues that what Moehling reveals in her analysis is not the futility of child labor legislation per se, but the failure of U.S. states to adequately enforce their laws. Even where factory inspection systems were created to implement child labor laws, the task typically proved difficult in the face of limited administrative resources, indifferent personnel, uncooperative courts, lenient penalties, and widespread evasions. In an era of patronage politics, factory inspectors were often chosen for political reasons, rather than on the basis of experience or competence. Even where they took their jobs seriously, parents and employers colluded to deceive them about working children’s true ages and the actual duration of their working hours. The sheer scope of workplaces to be monitored and the large number of poor families desperate for earnings overwhelmed even the most dedicated inspectors (Anderson Reference Anderson2021). For example, despite zealous efforts to root out and prosecute child labor violations, Illinois factory inspector Florence Kelley reported being unable to prevent an increase in illegal child labor (Illinois Office of Inspectors of Factories and Workshops 1895).

There is some evidence that the impact of child labor laws was conditional upon states’ administrative capacity. Enforcement depended not only on assiduous factory inspection but also on adequate record-keeping. For instance, between 1910 and 1930, U.S. states that supplemented child labor regulations with mandatory birth registration – which made it harder to conceal working children’s true ages – saw significantly less underage employment than states that lacked such requirements (Fagernäs 2012; see Pearson Reference Pearson2015 for more on birth certificates and child labor law administration). Moreover, child labor laws may have had a greater impact in some industries than in others. Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Christiansen and Philips1992) find that the decline in children’s participation in the U.S. fruit and vegetable canning industry between 1880 and 1920 was partly attributable to child labor laws, but they conclude that economic factors had a stronger effect. Finally, while child labor laws may not have made a significant contribution to the U.S.’s overall decline in factory child labor between 1880 and 1930, Manacorda (Reference Manacorda2006) argues that they did reduce child labor among underage children in the shorter time period between 1910 and 1920.

Despite evidence that child labor laws may have reduced child labor in certain industries, during certain time periods, or under certain administrative conditions, the overall scholarly consensus is that these laws were of limited effectiveness. Declines in child labor in the U.S. and the U.K. during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are instead attributed to changing technology, an increase in the demand for skilled and semi-skilled labor, an increase in the supply of unskilled adult labor (due, in the U.S. case, to immigration), and rising real wages (Goldin Reference Goldin1979; Osterman Reference Osterman1979; Nardinelli Reference Nardinelli1980, Reference Nardinelli1990; Cogan Reference Cogan1982; Parsons and Goldin Reference Parsons and Goldin1989; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Christiansen and Philips1992; Humphries Reference Humphries2010: 208; Hindman Reference Hindman2015: 237–49). Changing cultural attitudes also encouraged families to eschew sending younger children to work (Zelizer Reference Zelizer1985; Hindman Reference Hindman2015: 241) while increasing their acceptance of mothers’ labor force participation (Cunningham Reference Cunningham2000; Kleinberg Reference Kleinberg2005: 421). Some scholars (e.g. Nardinelli Reference Nardinelli1990) have concluded that the historical evidence supports tackling child labor indirectly by promoting economic development. The best thing to do, these scholars claim, is to let the market solve the problem: when economic growth raises adult wages and increases the demand for skilled labor, then children will naturally be drawn out of the labor force and redirected toward school.Footnote 2

However, there is a lack of historical research on the impact of social provision, as opposed to labor regulation, on children’s employment. Our study aims to fill this gap by examining whether mothers’ pensions reduced child labor rates in the early twentieth-century U.S. at the state and county levels.

Mothers’ pensions and child labor

In 1909, the White House hosted a “Conference on the Care of Dependent Children.” Over two hundred child welfare advocates and experts descended upon the capital to grapple with the problem of dependent children – the approximately 93,000 U.S. children residing in orphanages, children’s homes, and with foster families. Many of these children had been separated from their still-living biological parents because the parents could not afford to care for them. At the conclusion of the conference, the participants presented President Roosevelt with a list of fourteen unanimous resolutions. Among these was a call for the creation of “pensions” to enable poor but morally sound and “deserving” parents – especially widows – to retain custody of their children. The conference lit the spark for the “wildfire” spread of publicly funded mothers’ pensions across forty states, plus the territories of Hawaii and Alaska, between 1910 and 1920 (Leff Reference Leff1973; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992: 457).Footnote 3 An additional six states, as well as the District of Columbia, enacted mothers’ pensions programs over the course of the following decade (Leff Reference Leff1973).

The primary purpose of mothers’ pensions was to prevent family break-up due to poverty alone (Leff Reference Leff1973: 398–99; Howard Reference Howard1992: 193; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992: 424; Goodwin Reference Goodwin1997: 37; Crenson Reference Crenson1998: 17; Ward Reference Ward2005: 1). Less frequently recognized by contemporary historians, however, is that Progressive Era reformers also regarded pensions as a potential policy solution to the other major child welfare problem of the day: child labor (Leff Reference Leff1973: 409, 413; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992: 444; Gordon Reference Gordon1994: 37, 40).Footnote 4 If poor parents received aid, then perhaps they would keep their children in school rather than send them to work in factories or fields. Already in 1903, the National Consumers’ League had begun calling for widows’ pensions as an antidote to child labor. Its general secretary, the former Illinois factory inspector Florence Kelley, argued that if such pensions were adopted in manufacturing centers across the U.S., then “the child labor problem would be on the way to a prompt solution” (National Consumers’ League 1903: 19–20; see also Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992: 444). She suggested that pensions for widowed mothers be regarded as scholarships to allow children to stay in school until they reached the legal working age, an idea also endorsed by Jane Addams and by the Illinois Federation of Women’s Clubs (National Consumers’ League 1903: 19–20). As the Federation noted, barring children from paid employment only made sense if the state stepped in to ensure that the “real need” of widowed mothers was being met.

The link between mothers’ pensions and child labor continued to be made by reformers throughout the decade. At the 1909 White House conference, Charles Richmond Henderson, a University of Chicago sociologist and president of the National Children’s Home Society, pleaded in support of aid to poor mothers, “…let us not…permit some of the little children to go into factories and to work themselves to death in order to help support the family. The family must be supported, the mother must be cared for, but not at the cost of the children” (Proceedings of the Conference on the Care of Dependent Children 1909: 71; for more on Henderson, see Abbott Reference Abbott2010). In 1914, the delegates to the Third International Congress on the Welfare of the Child unanimously adopted a resolution recommending the universal adoption of mothers’ pensions “as the most effective method of checking truancy and child labor” (Third International Congress 1914: 432). In 1916, Hannah Schoff, president of the National Congress of Mothers and the PTA, wrote:

Some plan must be devised that would make it possible for the home to be sustained without the work of little children. Thus the nation-wide movement to secure mothers’ pensions has a meaning and purpose the scope of which is not fully realized even by some of its warmest advocates (Schoff Reference Schoff1916: 143).

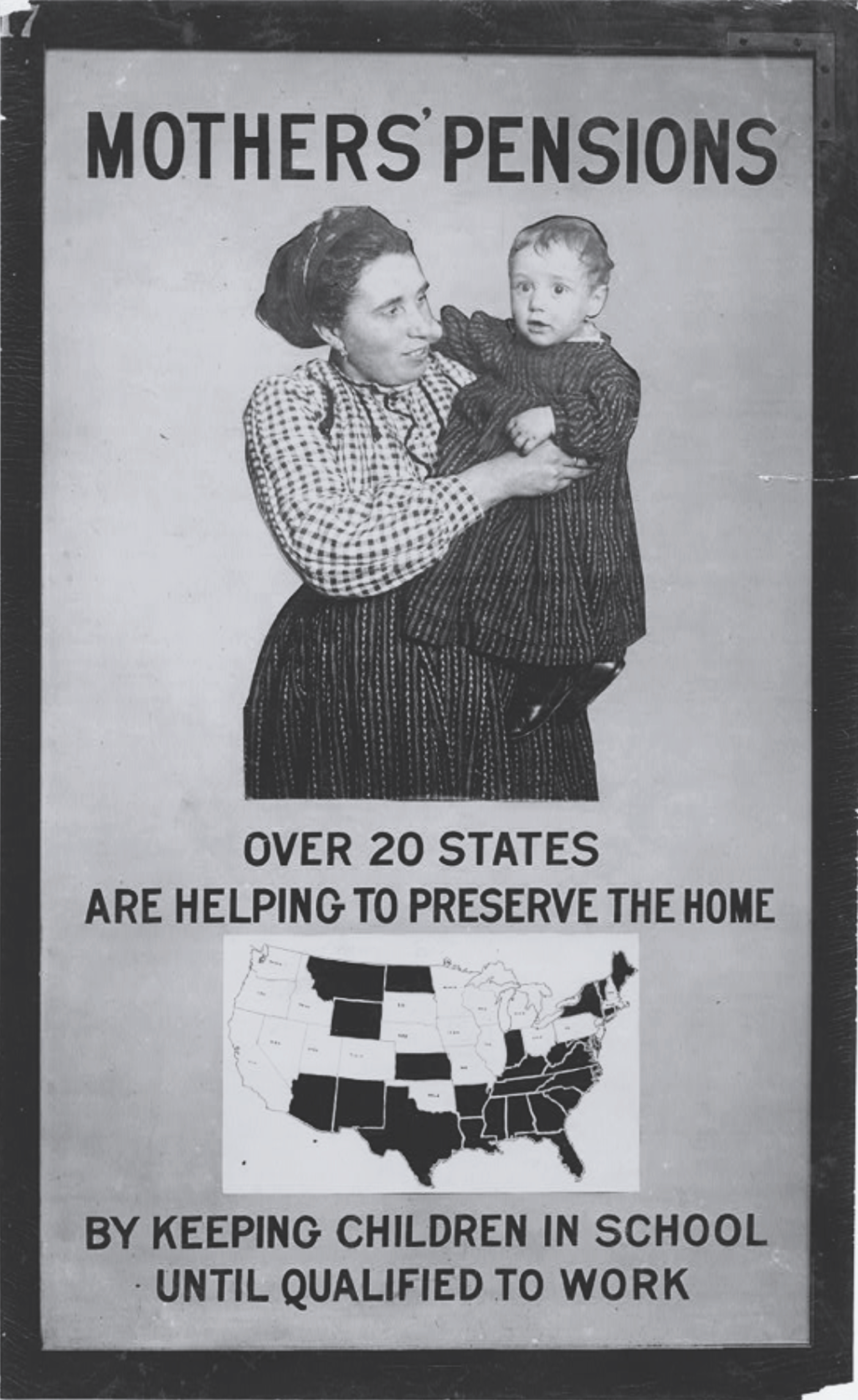

In 1919, the National Child Labor Committee, an advocacy group whose main purpose was to promote child labor laws, similarly hailed mothers’ pensions as a “practical way” to relieve hardship and enable children to forego premature employment (National Child Labor Committee 1919). Its educational materials proclaimed that the pensions kept children in school until they were old enough to work (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. National child labor committee poster, ca. 1914.

Source: Hine, Lewis Wickes, photographer. National Child Labor Committee collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. https://www.loc.gov/item/2018677695/.

Thus, although the main impetus behind mothers’ pensions was preventing family break-up, the idea that pensions could help combat child labor was one that many prominent Progressive Era reformers explicitly articulated. Their reasoning was that pensions would serve as a replacement for children’s foregone wages, not as a supplement to their earnings. However, whether families actually treated the pensions in this way – withdrawing their children from paid labor because pensions made it possible for them to afford to do so – is another question altogether. Moreover, whether pensions actually made a discernable impact on population-level child labor trends has yet to be explored. This is the aim of our paper.

Motivations for the present study

There are a number of reasons to expect a significant positive correlation between mothers’ pensions and child labor decline. First, existing research shows that mothers’ pensions had a significant effect at the individual level, although their impact on child labor has never been examined. Using matched data from archival mothers’ pension records and name-identified U.S. census, WWII, and death records, Aizer et al. (Reference Aizer, Eli, Ferrie and Lleras-Muney2016) analyze the long-run impact of mothers’ pensions on men whose mothers received a pension when they were boys. On average, these men lived one year longer, finished 1/3 year more schooling, had healthier weight and earned higher incomes in adulthood than those whose mothers applied for pensions but were rejected. Given these positive outcomes, it stands to reason that mothers’ pensions could have reduced child labor, too.

Unlike Aizer et al. (Reference Aizer, Eli, Ferrie and Lleras-Muney2016), however, we are interested in whether mothers’ pensions affected population-level, rather than individual-level, outcomes. In other words, we ask not whether a given child who actually received a pension was less likely to work, but whether state or county pension programs reduced the overall likelihood that children in the target population participated in paid employment. Assessing pensions’ aggregate impact on these children’s likelihood of working for pay is necessary if we are to determine whether any of the decline in child labor between 1880 and 1930 can be attributed to these social welfare provisions.Footnote 5

The second reason to expect that mothers’ pensions might have reduced child labor is that contemporary conditional cash transfer programs have been shown to have this effect. Many contemporary efforts to reduce child labor in developing economies have adopted a “carrot” rather than a “stick” approach – essentially paying poor parents to withdraw their children from work and send them to school, rather than penalizing them for violating child labor laws. Research suggests that these programs can in fact be a good way to reduce both illegal and legal child labor while improving family well-being. Indeed, they seem to be the most promising measure against child labor that has been tried – more effective than child labor bans, boycotts, trade sanctions, information or awareness campaigns, and compulsory schooling laws (although rigorous evaluations comparing these various approaches are scarce or non-existent) (Edmonds Reference Edmonds2007). For example, the Mexican Oportunidades program provides grants to poor mothers, conditional upon children’s regular school attendance, and rewards girls’ school attendance more generously than boys’. The program has been shown to significantly reduce children’s wage labor and to significantly lower the amount of time girls spend on domestic chores (Skoufias and Parker Reference Skoufias and Parker2001; Schultz Reference Schulz2004). Similar results have been demonstrated for programs modeled on Oportunidades in other countries (Edmonds Reference Edmonds2007; Baird et al. Reference Baird, McIntosh and Özler2010). Programs with explicit conditions (e.g., school attendance) that are monitored and enforced have a much greater positive effect on children’s school enrollment than programs that lack conditionality or that fail to enforce their requirements (Baird et al. Reference Baird, McIntosh and Özler2010; Baird et al. Reference Baird, Ferreira, Özler and Woolcock2014). However, nonconditional programs have also been shown to increase school enrollment and attendance (Baird et al. Reference Baird, Ferreira, Özler and Woolcock2014; Benhassine et al. Reference Benhassine, Florencia Devoto, Dupas and Pouliquen2015).

It is important to recognize, however, that there are major differences between contemporary programs like Oportunidades and early twentieth-century mothers’ pensions. First, mothers’ pensions were generally not conditional upon recipient children attending school, and they were never conditional upon their foregoing paid employment. Second, well-designed conditional cash transfer programs follow a strict, uniform protocol for determining eligibility, for setting the amount and duration of benefits, and for supervising families and monitoring compliance. Mothers’ pensions, on the other hand, were generally administered more arbitrarily and haphazardly, and localities usually lacked the capacity to enforce conditions in the rare cases in which these existed. Third, Oportunidades and similar programs are designed to allow rigorous evaluation, employing randomized controlled trials to assess effectiveness; mothers’ pensions were not and we lack the ability to measure their impact with the same precision.

Conditionality and administrative capacity: New Jersey and Pennsylvania

There are, however, important exceptions to this general lack of conditionality and supervision among early twentieth-century mothers’ pension programs. Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia all required school-age pension recipients attend school regularly in order for their families to continue receiving support (U.S. Department of Labor Children’s Bureau 1919: 53, 60, 65, 156, 190, 225). In most of these states, weak administrative capacity made enforcement of these eligibility requirements difficult. New Jersey, for example, did explicitly require program administrators to ensure that children attended school (U.S. Department of Labor Children’s Bureau 1919: 156), but its program lacked the capacity to closely supervise beneficiaries. The entire state of New Jersey had only eight part-time investigators in 1918. An agent of the Board of Children’s Guardians, which oversaw all child welfare programs and institutions in the state, lamented, “Our supervision of families, which is the most important, is still our problem. We have not been able to carry out the provision of the Law which requires us to visit each family six times a year.” The president of the board estimated that at most, two visits per year were feasible, and observed, “the ‘follow-up work’ in the widows’ homes is very far from creditable to the State, and it in no sense carries out the intent of the law” (New Jersey State Board of Children’s Guardians 1919: 4, 12).

A notable exception to this lack of conditionality and administrative capacity is Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania, where the silk industry relied heavily on child labor (Holleran Reference Holleran1996), was one of only three states to establish a distinct administrative entity exclusively responsible for overseeing mothers’ pensions (the other two were Delaware and Rhode Island (Davis Reference Davis1930: 580)). Its mothers’ pensions statute begins with a detailed plan of administration: pensions were overseen in each county by a volunteer board of trustees composed of between five and seven women, under the centralized leadership of a salaried state supervisor, also a woman, and two salaried assistants (U.S. Department of Labor Children’s Bureau 1919: 189–90). The supervisor’s main role was the “establishment of standards” relevant to “health, education, dietetics, and home care” (U.S. Department of Labor Children’s Bureau 1922: 21–23).

Pennsylvania’s law also stipulated that children attend school: “No payment shall be made on account of any child of proper age and physical ability unless satisfactory report has been made by the teacher of the school in which such pupil is enrolled stating that such child is attending school” (U.S. Department of Labor Children’s Bureau 1919: 190). In 1919, Pennsylvania raised the maximum age of pension eligibility from thirteen to fifteen for the express purpose of allowing fourteen- and fifteen-year-olds to continue their schooling rather than go to work. Counties that refused to accept the provisions of the statute pertaining to administration and eligibility were not allowed to institute a program (Eckman Reference Eckman1922: 18–19). The Pennsylvania supervisor’s annual report for the year 1918 expresses the seriousness with which program administrators tried to promote school attendance:

Good school records have from the beginning been recognized by the Boards as one of the first qualifications to Assistance. The Law is regarded as part of the educational machinery of the state and both mothers and children look upon the grant as something in the nature of a school scholarship. This has made for a high standard of attendance and progress. A school report covering attendance, punctuality, scholarship and health is received for each child of school age on uniform state blanks at least twice a year and in some counties as often as once a month. A school census of all children between six and sixteen under the care of the Fund was made last year by the State office and will be made biennially (Pennsylvania State Board of Education 1919: 12).

Such comments are absent from other reports we were able to find for this study. Given Pennsylvania’s special commitment to ensuring that pension recipients attended school regularly, we had a strong expectation of finding a significant effect of pension generosity on child labor in that state, in particular.

Mothers’ pension generosity: State laws, local implementation

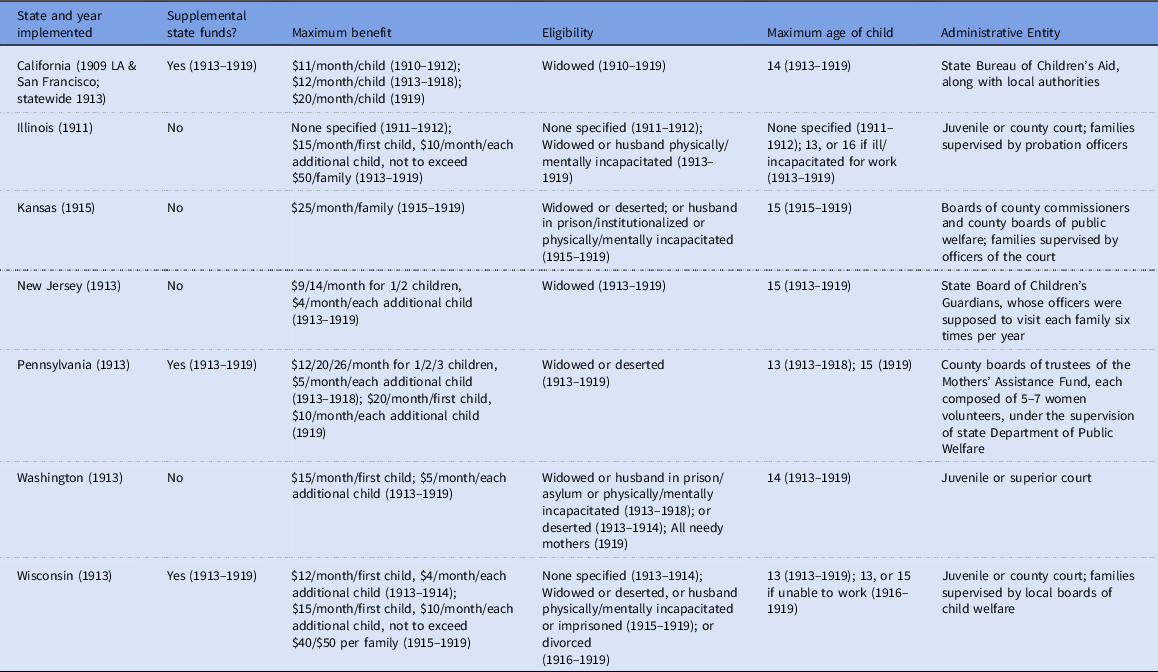

Mothers’ pension laws were state-level enabling laws: they authorized, but generally did not require, county and municipal governments to offer pensions to poor mothers and sometimes other guardians. There was a great deal of state-level variation with regard to the scope and generosity of mothers’ pension statutes (for examples, see Table 1). At the state level, laws varied along the following dimensions:

-

Funding: In most states, programs were to be funded entirely by local revenues. However, a few states allocated state funds to supplement local resources.

-

Maximum size of benefit: State laws set parameters determining the maximum (never the minimum) monthly cash amount that could be allocated for each child in a family, and they often also set a maximum amount for each family.

-

Eligibility: All state laws included unmarried, poor widows with dependent children in their programs. But many states also extended eligibility to mothers who had been abandoned by their husbands or whose husbands were physically incapacitated, imprisoned or institutionalized. A few states either explicitly included, or did not explicitly exclude, never-married or divorced single mothers, and a few included other guardians.

-

Maximum age: States capped the age of eligibility for dependent children. The most common maximum age was thirteen (particularly in states where fourteen was the minimum legal working age), but quite a few states granted aid to older children.

-

Administration: In a plurality of states, mothers’ pensions were administered by the juvenile, county, district, or probate courts. Various other entities were tasked with this responsibility in other states. These included state or local child welfare boards, boards of county commissioners, boards of children’s guardians, or state boards of education. Only three states set up a commission specifically to administer mothers’ pensions. In most cases, administrative entities operated with few resources and personnel, and their capacity to assess families’ needs or enforce eligibility criteria, such as children’s school attendance, was limited (Davis Reference Davis1930: 579–80; Machtinger Reference Machtinger1999).

Table 1. Statutory mothers’ pension benefits and requirements in seven selected states, 1910–1919

Not only was there significant variation across states with regard to the breadth of eligibility criteria and grant generosity, but variation existed within states, as well (Machtinger Reference Machtinger1999: 109–10). Even in states with mothers’ pension laws on the books, not every locality actually created a program; at their peak, only 60 percent of counties legally entitled to grant mothers’ pensions actually did so (Howard Reference Howard1992: 196). Among those that did, the percentage of legally eligible families aided and the average size of grants varied widely.

Our study tests whether the generosity of mothers’ pensions decreased children’s labor force participation among the most commonly targeted households: those headed by widows. We use full-count census data and a difference-in-difference approach to test this in two ways. First, we use U.S. Census data from 1880 to 1930 to examine whether the rate at which child labor decreased across states varied with how generous the state mothers’ pension law was. The second analysis is conducted at the county, not the state, level, and focuses on program implementation rather than statutory provisions. We use data from seven states to see if more generous counties – measured by county-level program expenditures – had larger declines in child labor after the adoption of mothers’ pensions.

To preview our findings, we find no relationship between mothers’ pension program generosity and child labor. States and counties with less generous child labor programs saw a decline in child labor that was no different from states and counties with more generous programs. Thus, we do not think mothers’ pension programs lowered child labor. We attribute this to the small size of the grants, the programs’ limited coverage, and their lack of conditionality on behaviors like school attendance or compliance with child labor rules. Even where eligibility was conditional upon school attendance, administrative capacity to enforce this requirement was generally quite limited (with the notable exception of Pennsylvania, as explained above). In what follows, we present data, methods, and results from both sets of analyses before discussing our overall conclusions.

State-level analysis

Data

We use full count U.S. Census data from 1880 to 1930,Footnote 6 excluding 1890 and 1910. Data from 1890 are unavailable owing to a fire that destroyed Census records. Although 1910 is the most proximate census prior to the passage of mothers’ pension laws, we exclude it because of differences in instructions given to census-takers. In 1910, census-takers were given special instructions about how to determine whether a child was gainfully employed. These instructions emphasized that women’s and children’s occupational information was just as important as men’s, and that it should never be taken for granted that children were not employed. Furthermore, census workers were told that children should be counted as having an occupation in any case where they “materially assisted” their parents in any work other than household work. In other years, this emphasis on rooting out child labor was omitted from the instructions. This change in the instructions may have caused the number of child laborers to be over-counted in 1910 relative to other years, as U.S. Census officials later acknowledged (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1924: 16–17). Our preliminary analyses showed that child labor was higher in 1910 than in 1900 or 1920, suggesting that these instructions substantially altered patterns of recording child labor. We therefore exclude the 1910 data and rely on the longer trends from 1880 to 1930 (excluding 1890) within each state.

We restrict our analysis to children between ages ten and fifteen (inclusive). Although children ages ten to thirteen were eligible in every state, one component of our generosity measure is precisely whether older children were eligible, and so we examine trends separately among children age thirteen and under, and children age fourteen and fifteen. Further, since poor, unmarried widows with dependent children were eligible for mothers’ pensions in every state, we only retain children residing in female-headed households where the head of household is a widow.Footnote 7 Because mothers’ pension recipients were overwhelmingly white (Ward Reference Ward2005), we exclude non-white children from our analysis.Footnote 8

Variables of interest

Our outcome variables are thus the labor force participation rate of white children ages ten to thirteen and white children ages fourteen and fifteen living in widow-headed households. We generate these rates from full count census data for each state in each of the four Census years (1880, 1900, 1920, and 1930). To generate the labor force participation rate, we code any child with a listed occupation as working.

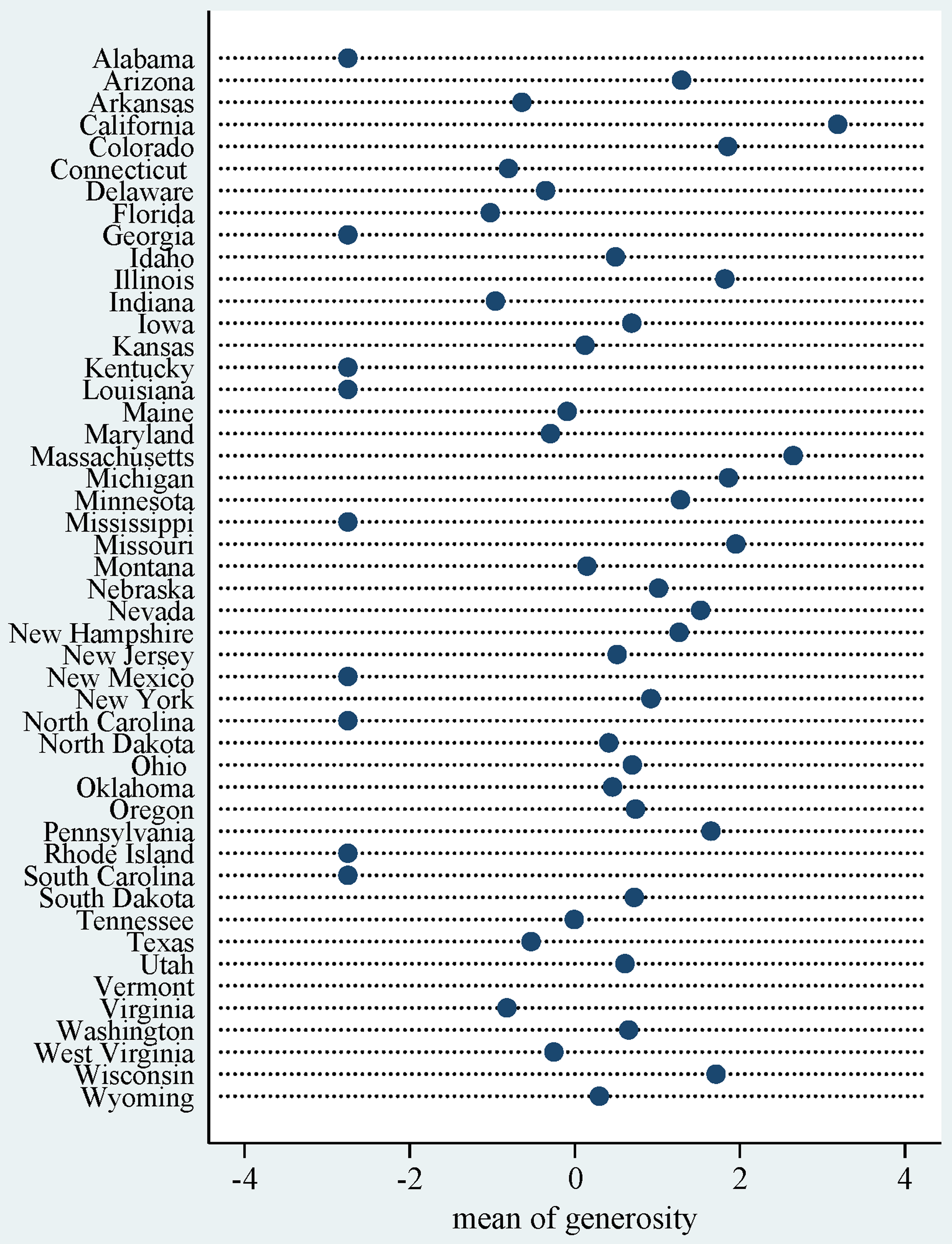

Our independent variable of interest is a composite of four indices of the generosity of a state’s mothers’ pension law between 1910 and 1920, based on the dimensions discussed above. The first of these is the number of years the state had a mother’s pension law in effect between 1910 and 1920, which ranged from 0 to 10. The next is the maximum possible benefit allotted to a family of four (almost always, one mother and three children). This varied not only across states, but also over time within states as benefit levels were adjusted. For each state, we averaged the maximum benefit for a family of four across the decade, assigning a 0 for years in which the state had no pension instituted. Thus, this figure ranged from $0 to $42 ($0 to $1,083 in 2020 dollars) per month.Footnote 9 The next generosity indicator was the number of years that state funds were allocated to supplement local funding of mothers’ pensions. Finally, we included an indicator for the maximum allowable age of the child. This also changed over time within states, so we averaged the maximum age allowed for each year that the state had a mothers’ pension law in effect. States with no law received a 0 for each component of the index. We conducted a principal component analysis on these four indices, which produced one salient factor, henceforth referred to as “generosity” with an eigenvalue of 2.59.Footnote 10 Figure 3 presents each state’s generosity score on this combined measure.Footnote 11

Figure 3. Generosity of mothers’ pension laws between 1910 and 1920, by state.

Control variables

We include state-level controls for aggregate characteristics of children and adults in the state, state-level economic structure, and state revenues and expenditures. From full-count Census data of ten- to fifteen-year-old children living with widowed mothers, we derive the average age of children and the percent of children that are female. Because foreign-born children might have been more likely to work, we control the share of children that are foreign born. We also control for adult characteristics derived from 1 percent samples of all adults ages 18–65. These include the percentage of adults residing on farms and in urban areas, and the percentage of adults with occupations, to control for the economic structure of the state. In addition, we control for adult literacy and the percentage of adults that are foreign born.

To control for the greater prevalence of child labor across regions, which may be correlated with pension generosity, we include an indicator for whether or not a state is in the South. We also include economic and governmental characteristics for each year. This includes a control for the overall level of industrialization to address the possibility that both child labor and a state’s mothers’ pension generosity are functions of a state’s dependence on industrial labor. It is also possible that mothers’ pension generosity and/or child labor participation are related to state finances or a state’s overall commitment to social provision. Thus, we also include as a control a measure of total state and local revenue per capita and the state’s educational expenditures per capita.Footnote 12

Modeling strategy

We use a difference-in-difference approach to see whether the decline in child labor differed by states’ mothers’ pension generosity. Because states had different levels of child labor before adopting mothers’ pensions, it is inappropriate to examine the link between the generosity of pensions and child labor force participation rate. Instead, we examine how children’s labor force participation changed after the adoption of mothers’ pensions. Did more generous states have larger declines in child labor comparing years before the passage of laws (1880, 1900) to those after the passage of laws (1920, 1930), even after adjusting for a state’s demographic characteristics, economic structure, revenue and education expenditures? Mathematically, the difference-in-difference is captured by including an indicator variable for year (before/after 1920), our generosity scale, and an interaction between the two in each model. We also include a linear time trend to account for the overall decline in child labor from 1880 to 1930.

We aggregate to the state level in order to examine how state policy shifts are associated with the overall rate of child labor. Because we have multiple observations for states, we add a random intercept at the state level to control for unobserved variation between states. Because statutory generosity does not vary within states, we do not use fixed effects to eliminate unobserved variation, as we could then not test the effect of generosity.

The model takes the following form: Y it = B 00 + B 1n G i + B 2 T it + B 3 T it *G i + B k X it + U i , where G j represents state-level generosity, T j is a dummy variable representing whether the year is 1880/1900 or 1920/1930, X i represents a series of state-level covariates that vary over time, and U represents a random intercept term at the state level.

Trends over time

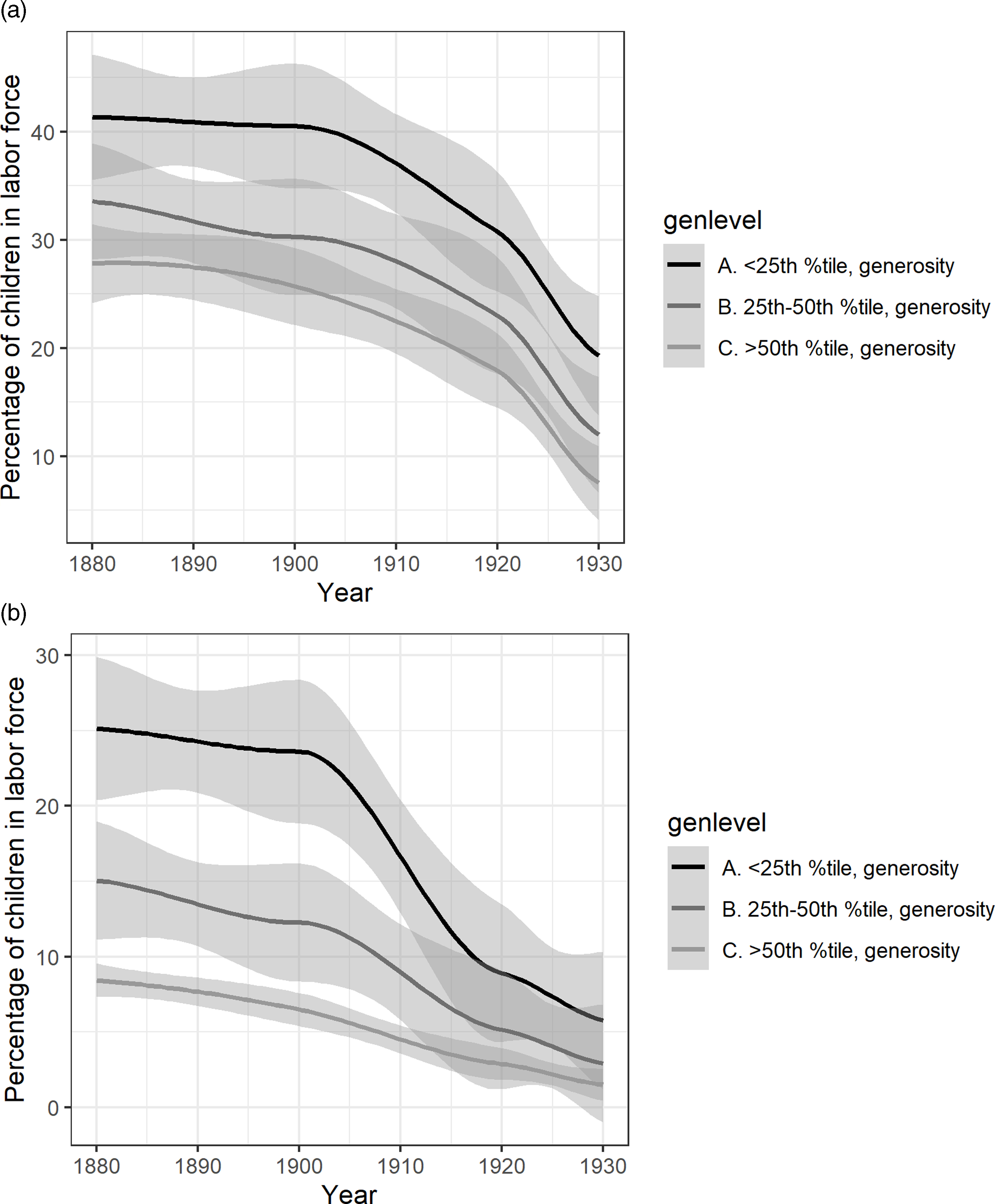

Before examining results from our multivariate regression with difference in difference, we show state-level trends in child labor for groups of states with different levels of generosity in Figure 4. We expected that the effect of mothers’ pension laws – which were passed between 1910 and 1920 – would manifest as a bigger drop in more generous states than in less generous states. However, Figure 4 shows that this is not the case. Instead, we find that states that ended up passing the most generous laws already already had lower rates of child labor in 1880 and 1900. States that did not pass laws or that passed less generous laws had higher rates of child labor in 1880 and 1900, and rates of child labor declined more rapidly in less generous than in more generous states. This is true for both older and younger children, although the timing of declines differ.Footnote 13

Figure 4. Percent of children working by generosity of state mothers’ pension law. Panel A: 14- and 15-year-olds. Panel B: 10- to 13-year-olds.

To summarize, we find (1) lower rates of child labor in more generous states, particularly in earlier years and (2) more generous states have smaller decreases in child labor between 1900 and 1920. Still, these patterns could be explained by state-level controls. For example, if industrialization is positively correlated with both generosity and decreases in child labor, controlling for it would reduce the differences in child labor declines across states. To test such possibilities, we estimate a random-effects regression model in which we examine the link between state-level generosity and changes in child labor rates while controlling for a wide range of economic and demographic characteristics at the state level (shown in Model 2, Appendix 1 in supplementary materials).

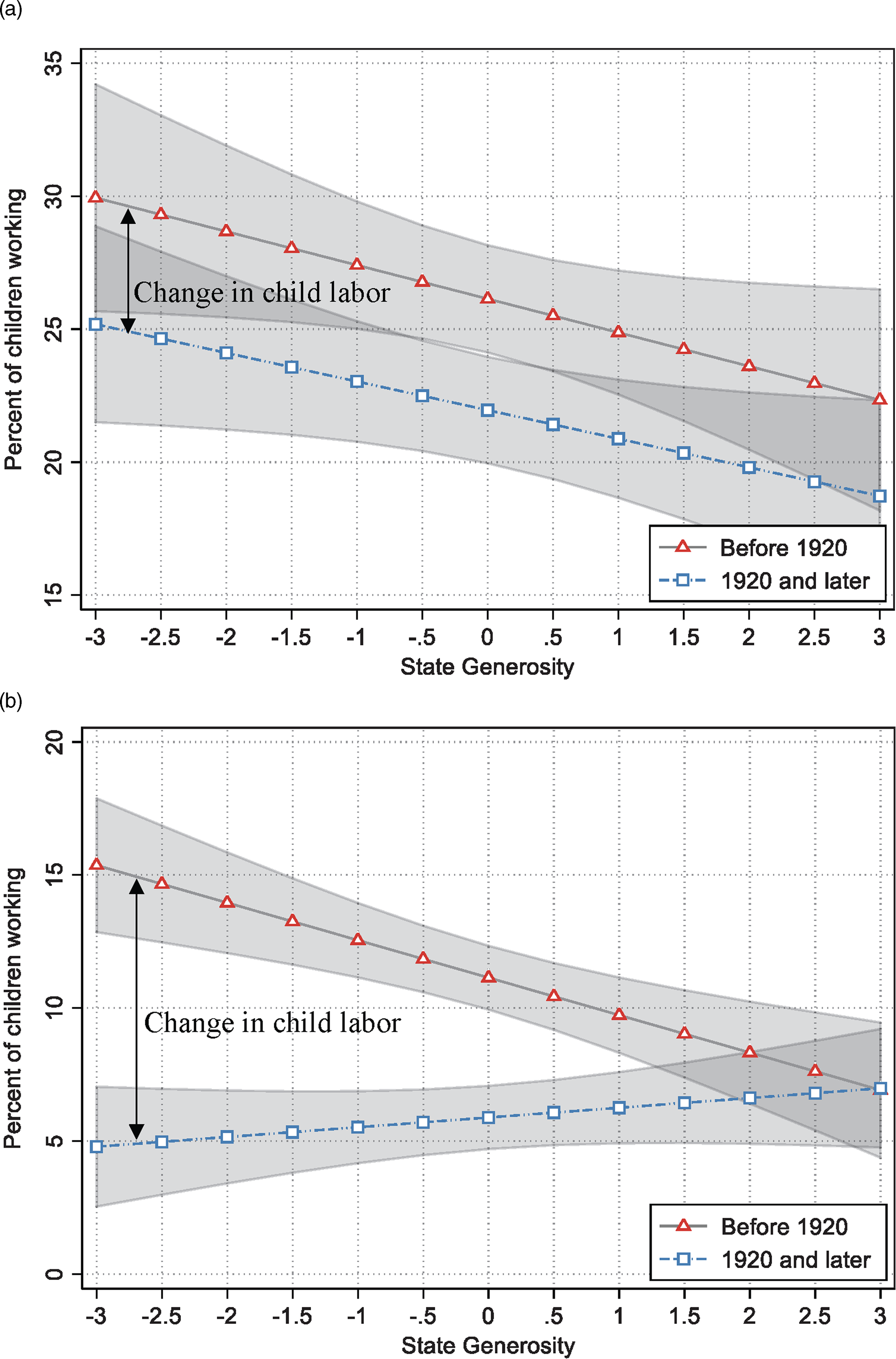

Figure 5 presents predicted rates of child labor from model 2, with the first panel showing older children and the second panel showing younger children. In each panel, the top line indicates rates of child labor, on average, in 1880 and 1900 by the generosity of the mothers’ pension policies that states ended up passing, net of controls for state characteristics. The bottom line shows rates of child labor in 1920 and 1930, after mothers’ pensions were passed. The difference between these lines, illustrated by the double-ended vertical arrow, shows the change in rates of child labor after passage. Panel A indicates that although there is a link between state-level generosity and child labor in 1920 and 1930, the link was similar prior to the passage of mothers’ pension laws. For younger children, in Panel B, there is no relationship between state-level generosity and child labor in 1920 and 1930, after laws were passed. However, states that went on to pass more generous laws had lower rates of child labor before 1920, even after controlling for state characteristics. Thus, the decrease in child labor for the least generous states is larger than the decrease in child labor in the most generous states.

Figure 5. Predicted probability of child’s work by generosity of state mothers’ pension law, before and after passage; from model with state-level controls. Panel A: 14- and 15-year-olds. Panel B: 10- to 13-year-olds.

Note: Predicted probabilities are generated from Table 1, Appendix 1. Controls include the average age of children, the percent of children that are female, the percent of children that are foreign born, the percent of adults residing on farms residing in urban areas, working, and foreign-born, whether the state is in the South, the state’s level of industrialization, state and local revenue, and the state’s educational expenditures. To generate predicted probabilities, we set all controls to their mean values.

These results suggest that, net of other factors, generous mothers’ pension laws (1) did not reduce child labor at the state level and that (2) there was little association between the generosity of laws and rates of child labor after passage. One possible explanation for this unexpected finding is that mothers’ pensions were not administered in a way that prevented families from combining pension income with children’s earnings. Another is that the programs simply did not reach enough families, or offer large enough benefits, to have an impact at the population level.

County-level analysis

In the state-level analysis presented above, our assessment of a state’s mothers’ pension generosity is based on the text of its law. The analysis assumes that states that passed mothers’ pension laws effectively implemented them across the board. It further assumes that this implementation affected individual children of widows across the state equally. However, mothers’ pensions were implemented at the county level and both their presence and generosity varied considerably within states (Howard Reference Howard1992: 195–96). Even in states that enacted a mothers’ pension law, not every county put a program in place; among those that did, program expenditures and coverage varied widely. We therefore examine how counties’ implementation of mothers’ pension programs affected child labor at the county level.

Data and methods

To account for this county-level variation, we analyze counties in states for which we have mothers’ pension expenditure data for any year between 1914 and 1919: California, Illinois,Footnote 14 Kansas, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Washington, and Wisconsin.Footnote 15 These represent a diverse selection of states with regard to geographic location, dominant economic sector (agriculture vs. manufacturing), and urbanization. We collapse individual-level observations from full count census data to create county-level variables for child characteristics and 1 percent census data for adult characteristics. Our sample consists of 455 counties across the seven states.

As in the state-level analysis, we use random intercepts. Here, we include random intercepts at the county level to assess whether county expenditure per capita on mothers’ pension programsFootnote 16 affected the change in child labor rates while accounting for unobserved sources of variability that might lead a particular state or county to have a higher or lower rate of child labor.

Our key independent variable is annual expenditures per child in a widowed household in the prior year closest to 1920 for which data are available. The denominator is calculated from full-count Census data for 1920. We use the total number of children age 13 or under in widow-headed households,Footnote 17 rather than the number of beneficiaries, because this better captures the impact of the program on potential beneficiaries. If we used only beneficiaries, programs that were small even in large counties might appear to offer substantial support. Expenditures per child ranged from 0 in counties with no program to $120 in Colusa County, California (a county with only 105 children in widowed households), with a mean of $9.34.

As in the state-level analysis, we include county-level controls derived from full-count data for widow-headed households containing children between the ages of ten and fifteen for the average age of children, children’s literacy, and the percent of children that are female. For adults, we control for literacy, the percent of adults that are foreign-born, female, and living on farms, in urban areas, and working in manufacturing, derived from 1 percent samples of adults. To control for the possibility that county wealth affected not only mothers’ pension expenditures but also the prevalence of child labor, we also include a control for a county’s wealth per capita in 1900.Footnote 18

Results

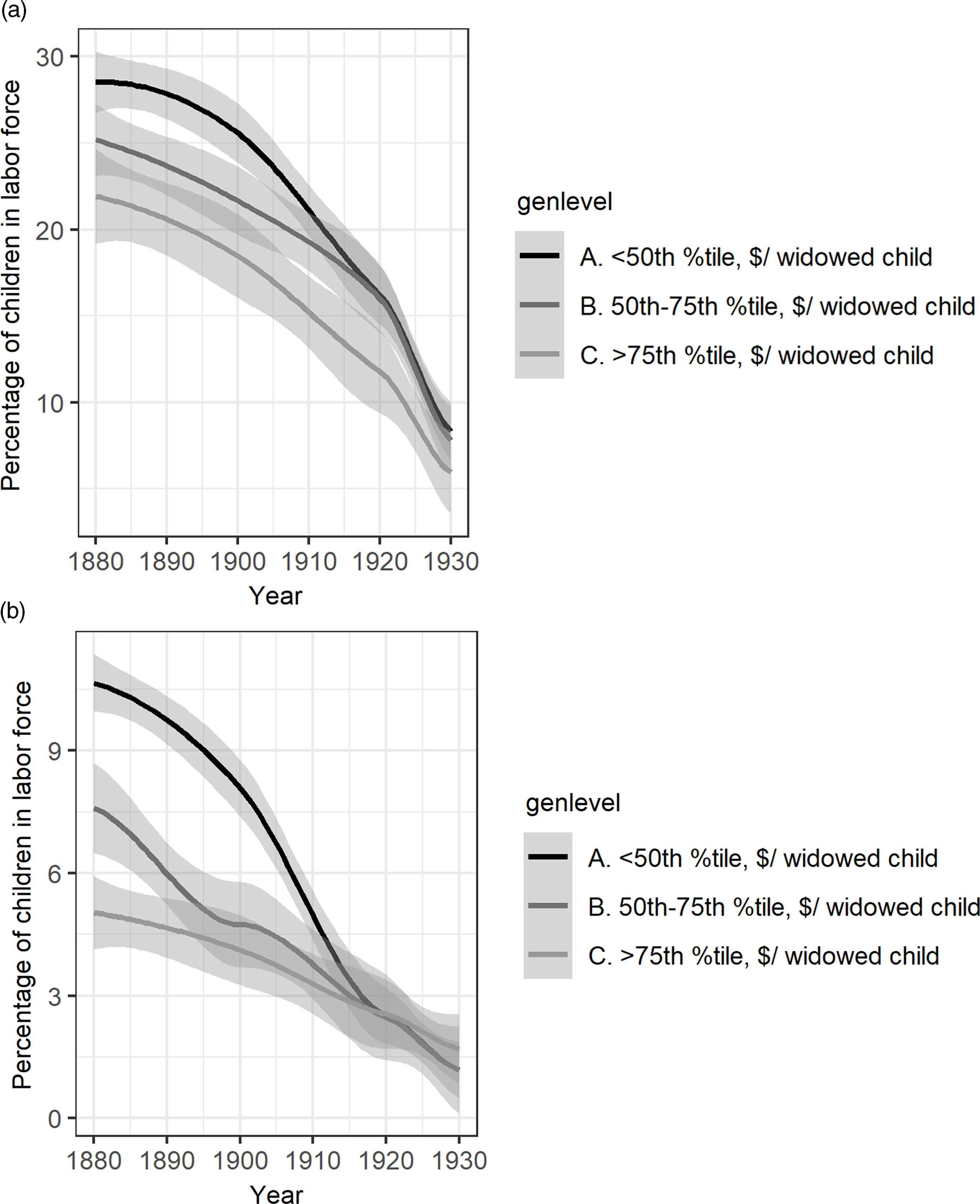

Figure 6 shows trends in child labor by counties’ level of generosity. Panel A shows the decline among 14- and 15-year-old children. The darkest line indicates counties that spent relatively little per capita after the passage of mothers’ pension legislation in their states. Within the group of counties that had low benefits, 22 percent did not pay any mothers’ pension benefits in the period we observed. These counties had higher rates of child labor in 1880 and 1900 but declined more rapidly than other counties. Counties that eventually had more generous distributions of mothers’ pensions saw lower levels of child labor in early years, but in 1920 and 1930, after laws had been passed, there appear to be no differences between counties based on the level of generosity. The pattern in Panel B, among younger children, is similar, in that counties with lower spending per child after passage began with higher child labor rates and all counties converged to roughly the same point after the passage of legislation (in 1920–30).

Figure 6. Percent of children working by expenditures per widowed child by county. Panel A: 14- and 15-year-olds. Panel B: 10- to 13-year-olds.

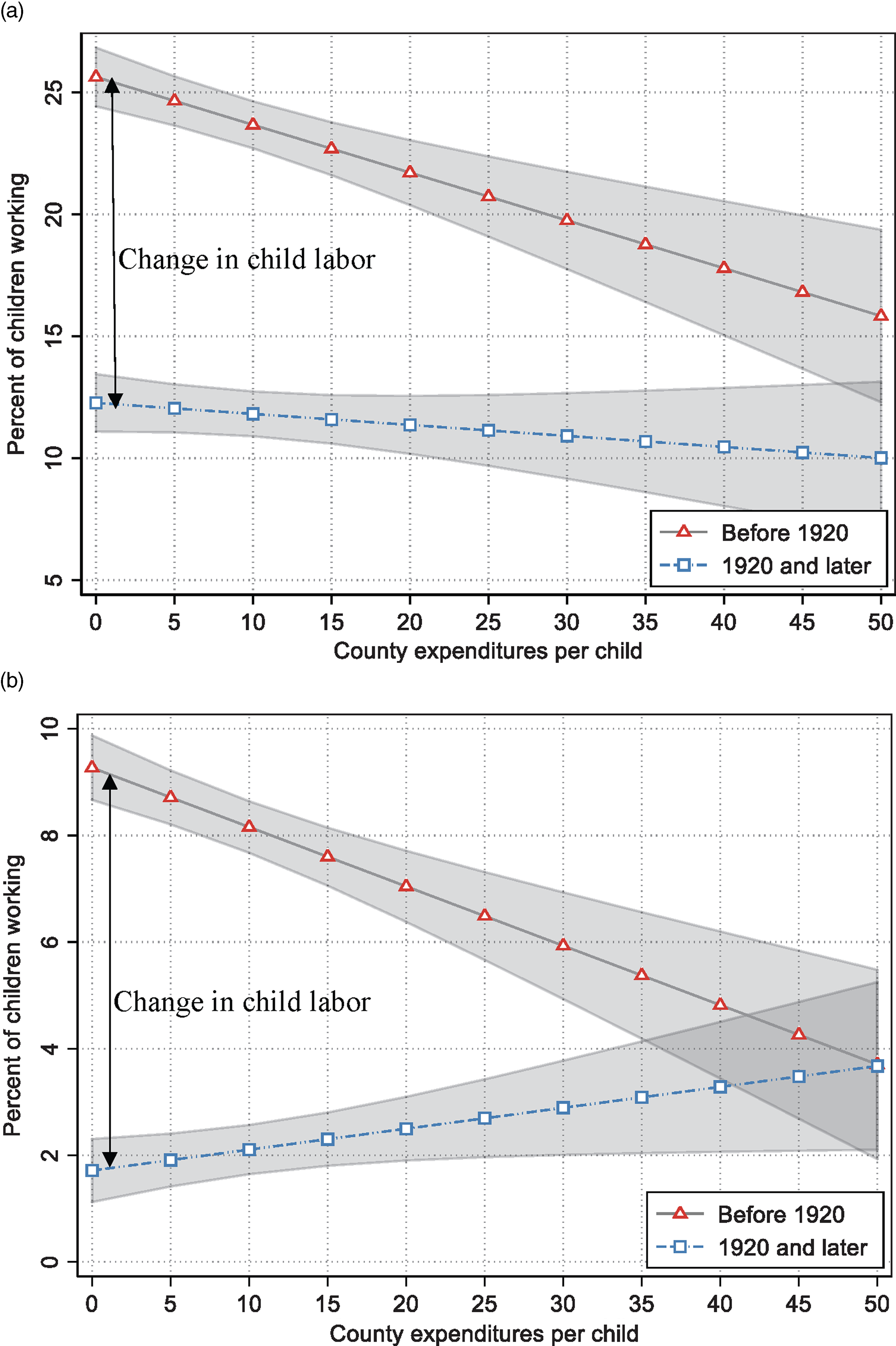

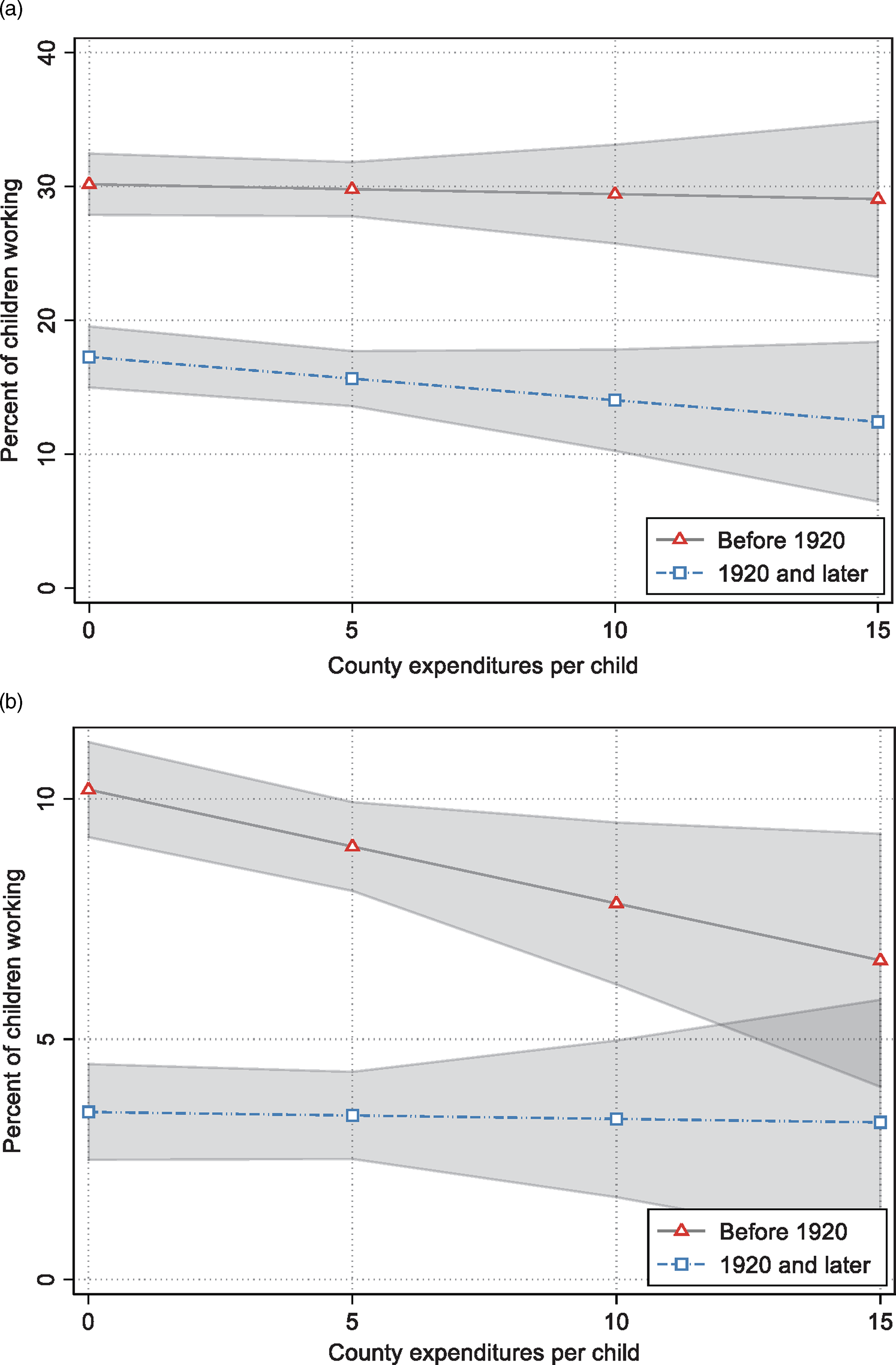

As with our earlier analysis, we investigate whether the inclusion of controls alters this relationship. It does not. Figure 7 shows predicted rates of child labor by counties’ expenditure per child. Counties that went on to spend less per child (toward the left side of the x axis) had higher levels of child labor prior to the passage of laws. After passage, those same counties had levels of child labor that are not significantly different than counties with higher levels of spending. Although in 1920 and 1930, counties that spent more appear to have higher rates of child labor than counties that spent less, the differences are not statistically significant. Overall, and given our other results, we are inclined to read this set of analyses as yet more evidence that mothers’ pension programs had no effect on child labor within the target population.

Figure 7. Predicted probability of child’s work by county expenditures before and after institution of mothers’ pensions; from model with county-level controls. Panel A: 14- and 15-year-olds. Panel B: 10- to 13-year-olds.

Note: Predicted probabilities generated from Table 2, Appendix 1. Controls include the average age of children, children’s literacy rate, the percent of children that are female, the percent of adults foreign-born, adult literacy, the percent of adults that are female, the percent of adults living on farms, in urban areas, and working in manufacturing, and the county’s wealth per capita in 1900. To generate predicted probabilities, we set all controls to their mean values.

Discussion

Mothers’ pensions evidently did not reduce the likelihood that children of widows worked for pay. Why not? While we cannot answer this question definitively, we investigated three likely explanations. First, and most important, we examined data on program coverage – the share of needy households receiving aid – and found that programs fell short of need. Our estimated percentage of pension recipients among widow-headed households with children age 13 and under is just 5.2 percent in Pennsylvania, 11.8 percent in Illinois, 12.2 percent in New Jersey, 25.5 percent in California, and 28.3 percent in Wisconsin.Footnote 19 Of course, not all widows were poor, but these low rates of coverage suggest that many poor widows with children, as well as other poor single mothers, were not receiving grants they were legally eligible for. For instance, in Pennsylvania in 1918, program administrators reported that only an estimated 30 percent of eligible families were receiving pensions (Pennsylvania State Board of Education 1919: 7).

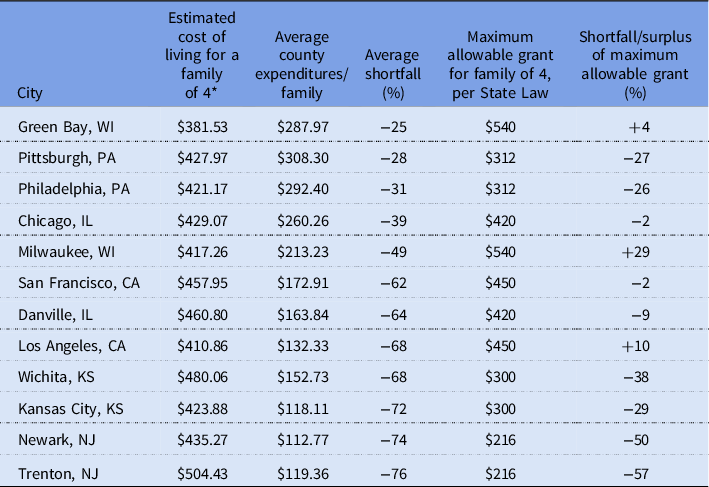

Second, grants were small and not sufficient to cover a family’s cost of living (US Department of Labor 1922: 10–11). Table 2 presents shortfalls in mothers’ pension grants relative to the estimated cost of living for a family of four (mother plus three children) in twelve cities.Footnote 20 In each city, average monthly shortfalls were substantial, ranging from 25 to 76 percent of a family’s estimated needs. Even if families received the maximum allowable grant, they still faced significant shortfalls in most cities. Such shortfalls would have created strong incentives for families to combine aid with children’s earnings.

Table 2. Estimated monthly shortfalls of mothers’ pension grants for families of four relative to cost of living in 12 cities

+ Includes food, clothing, rent, fuel/lighting, furniture, and incidentals.

Third, state mothers’ pension statutes generally did not stipulate that children attend school regularly, or that they refrain from child labor, in order to be eligible for aid. In our sample, the exceptions to this were Pennsylvania and New Jersey, although evidence from administrative agency reports suggests that only the former had the administrative capacity to actually enforce its schooling requirements. In the end, though, these variations made little difference with regard to reducing child labor at the population level. As shown in Figure 8, generous Pennsylvania counties did not see a significantly greater drop in child labor rates compared to less generous counties.

Figure 8. Predicted probability of child’s work by county expenditures in Pennsylvania before and after institution of mothers’ pensions; from model with county-level controls. Panel A: 14- and 15-year-olds. Panel B: 10- to 13-year-olds.

Note: Predicted probabilities are generated from Table 3, Appendix 1. Controls include the average age of children, children’s literacy rate, the percent of children that are female, the percent of adults that are foreign born, literate, female, living on farms, in urban areas, and working in manufacturing, and the county’s wealth per capita in 1900. To generate predicted probabilities, we set all controls to their mean values.

Evidently, greater supervision of recipient families could not make up for the fact that grants fell well short of the cost of living and only reached a small fraction of eligible widows (Pennsylvania State Board of Education 1919: 4, 7).

Limitations vs. strengths

Our study suffers from several disadvantages, all due to limitations in the historical data we were able to compile. First, predicted probabilities of child labor are derived from 1920 census data, but county-level data on program generosity is often from several years prior; for example, for California, it is from 1915. Lack of comprehensive data for all years in which a program was in effect prior to 1920 means that we may have under- or overestimated programs’ impact on child labor in some cases. Second, we were only able to find usable county-level data for seven states; it is possible that our results would have been different if we had been able to include more states. Third, the expenditures data we use are likely somewhat inconsistent across states and counties; in particular, some states may have included administrative expenses in their expenditures data while others did not. Fourth, our population includes only widow-headed households with children and not other poor single mothers who would have been eligible for aid in some states; although we control for individuals’ socioeconomic status using proxy measures, our results may be skewed by our inability to focus precisely on the population actually targeted for mothers’ pension programs in each state. Finally, our outcome measure is crude; it treats all child labor the same, and cannot differentiate between children who worked only part time or intermittently from those who worked full time. It could be that mothers’ pensions reduced the number of hours children worked, perhaps allowing them to combine school with wage labor, but our data do not allow us to explore this possibility.

Despite these disadvantages, our study moves knowledge on this topic forward. It is the first known study of the impact of mothers’ pensions on the probability of children’s labor force participation in U.S. states and counties. It draws on a wealth of primary historical data, including qualitative data from state and federal agency reports as well as quantitative data from these reports, a variety of historical data sets, and published primary sources. Furthermore, we use full-count Census data, eliminating any issues related to sampling error. We ensure our results are robust across different model specifications, and, lastly, we analyze the available data at multiple levels, allowing us to discover patterns at the granular county level which are obscured by state-level observation.

Conclusion

At the state level, after controls for state-level variables, we find no effect of mothers’ pensions on the likelihood that children of widows worked for pay. In 1910, more generous states already had lower child labor than less generous states for both older and younger children. Furthermore, the decrease in child labor between 1910 and 1920 is larger for less generous states. By 1920, after adjustment for state-level economic characteristics and individual and household characteristics, we find that the difference between generous and non-generous states in the likelihood of child labor disappeared for children age 10 to 13. Patterns are similar at the county level: before the passage of mothers’ pension laws, counties that went on to spend more on pensions generally had lower rates of child labor than counties with lower expenditures, and there is little evidence to suggest that higher spending led to more rapid declines in child labor.

The broader implication of these findings is not that policy interventions to combat child labor are pointless. As mentioned, contemporary conditional cash transfers have repeatedly been shown to decrease labor force participation and to increase school attendance among young beneficiaries. Rather, the finding suggests that, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, U.S. states chose not to adequately invest in policy interventions that could have reduced child labor, despite the issue’s salience among reformers and the public at large. States passed child labor laws, but failed to adequately enforce them. Likewise, they created mothers’ pensions to aid poor families, but they did not fund or administer these programs adequately. Mothers’ pensions reached few families and fell short of living expenses, and so poor families – in all likelihood, including many of those who received a pension – continued to depend on children’s earnings to survive. Pension programs also did not make aid conditional on children foregoing paid employment, and they typically did not make it conditional upon children’s school attendance. Even where school attendance was required, program administrators generally lacked the resources needed to ensure compliance. For these reasons, mothers’ pensions were a missed opportunity to steepen the decline in child labor in the early twentieth-century U.S.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2022.33.