Obesity in early life has immediate consequences on health, such as dyslipidemia hypertension, abnormal glucose tolerance and other risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD)(Reference McCrindle1,Reference Must and Strauss2) . It is a precursor of adulthood obesity(Reference Freedman, Khan and Serdula3), leading to development of cardiometabolic risk factors like atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes(Reference McCrindle1,Reference Biro and Wien4) . According to data from the World Health Organisation (WHO), in 2012, chronic non-communicable diseases were responsible for 38 million deaths worldwide(5). From an economic point of view, chronic non-communicable diseases are responsible for high public financial expenditures, with obesity being especially linked to sky-rocketing medical costs(Reference Dobbs6).

In the last decades, the global prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents has exponentially increased(Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Hall7). In 2008, it was estimated that 170 million people less than 18 years old were classified with overweight or obesity(Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Hall7); and projection models show that, by 2030, 30 % of children and adolescents will be affected by these conditions in the USA(Reference Wang, Beydoun and Liang8). Estimates by WHO show that most youths with excess weight live in low- and middle-income countries, where the rates have been increasing even faster compared to high-income countries(9).

In Brazil, overweight and obesity among youth is an important public health concern due to its increasing prevalence. Data from the Family Budget Survey (POF), conducted between 1974 and 2009, show that obesity among adolescents increased from 0·4 to 5·9 % in boys and from 0·7 to 4·0 % in girls(10). More recently, the Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents (ERICA), which evaluated 73 399 Brazilian adolescents aged 12 to 17 years, revealed that 17·1 % and 8·4 % of adolescents had overweight and obesity, respectively(Reference Bloch, Klein and Szklo11).

Differences between Brazilian regions are striking in many ways, with social, demographic, cultural and economic factors particularly influencing nutritional status. The South and Southeast are more developed and industrialised regions, Midwest is in development trough agribusiness, while the North and Northeast regions are characterised by the highest social inequalities in Brazil. Access to healthcare services is much lower in the North and Northeast regions compared to the rest of the country. Despite very different epidemiological profiles, regional information about the trends in prevalence of excess weight among adolescents are scarce. A previous systematic review that included 28 Brazilian studies showed an overall prevalence of obesity among adolescents of 14·1 %, but results were not stratified by region or decades, therefore making it difficult to generalise such rate for the whole country(Reference Maria Aiello, Marques de Mello and Souza Nunes12). The diversity between Brazilian geographical areas highlights the necessity of collecting data from studies conducted in different cities and states of Brazil in order to obtain a better epidemiological profile of youth obesity across the country during the past decades.

In order to have a better understanding of excess weight trends in Brazilian adolescents, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies that presented data about weight status in this population. Our objective was to estimate the prevalence of overweight and obesity in Brazilian adolescents, considering regional and temporal variations. We hypothesised that overweight and obesity would significantly increase over the years in all regions of Brazil.

Methods

The protocol for this review was registered and published on the Prospero database (Registration number: CRD42018107055). The report of this systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement(Reference Liberati, Altman and Tetzlaff13,Reference Moher, Shamseer and Clarke14) .

Search strategy

The search strategy was performed in Portuguese and English languages, without restriction of publication data, by the main investigator. The literature search combined the following keywords: overweight, obesity, adolescents and Brazil. The terms were searched in four databases: MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online/PubMed), EMBASE (Elsevier), Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) and Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde (LILACS). Full search strategy is shown in the supplementary material (Table S1). All potentially eligible studies were considered for review. Duplicate studies were excluded. The software EndNote version X7 (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY) was used for reference selection management. The last search was performed in June 2020.

Study eligibility

Two pairs of reviewers (MS and MRG; JAR and MM) analysed study eligibility independently. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the studies included in the meta-analysis. The studies were selected based on the following criteria: cross-sectional and cohort studies that reported the prevalence of overweight/obesity among Brazilian adolescents (10–19 years old). Weight and height had to be measured to calculate the BMI; studies based on self-reported data were excluded.

Fig. 1. Flow diagram of study selection.

Populations in the studies had to be selected through random sampling or census, and studies that included less than 300 individuals were excluded. A sample size calculation was performed considering the following parameters: prevalence of overweight/obesity of 25 %(Reference Bloch, Klein and Szklo11), power of 80 % and confidence level of 95 %. These parameters required a sample of around 300 adolescents. This criterion was adopted to help us in the screening processes, avoiding studies with non-representative sample at local level, at least, or those with a large margin of error.

Additionally, studies that assessed only specific subgroups not representative of its geographical strata were considered ineligible. Systematic reviews, narrative reviews, clinical trials, case–control and case reports studies, as well as studies using overweight/obesity diagnostic criteria for adults were excluded from this review. Studies in English and Portuguese were included. A third investigator (FVC) solved disagreements between reviewers.

Data extraction

Two pairs of reviewers (MS and MRG; JAR and MM) separately evaluated the studies for data extraction. Titles and abstracts were reviewed and publications were selected for reading in full, if they presented data according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria or had insufficient information in the abstract to make a decision. Studies from the same population were assessed and the article with more details was included. In relation to studies with insufficient information, a request was sent to the authors; if they did not reply, the study was excluded from this review.

Data were entered in a pretested Microsoft Office Excel™ spreadsheet based on the Strengthening in Epidemiology Statement (STROBE) checklist(Reference von Elm, Altman and Egger15). The absolute, rather than relative value of each variable, was obtained. Any discordance between the data extracted was discussed until consensus was reached. Captured variables included study name, date of publication, year of data collection, study design and type (household survey, school-based survey, etc), age range, region, diagnostic criteria for overweight and obesity and estimated prevalence of overweight and obesity (overall and by sex).

Risk of bias

We assessed the risk of bias for each selected study using a ten-item tool that was specifically developed for population-based prevalence studies(Reference Hoy, Brooks and Woolf16). The tool is divided in two domains – external validity (four items) and internal validity (six items). After evaluation of the ten items, each item received a score of 1 (yes) or 0 (no). According to overall scores, a summary assessment deemed a study to be at low (9–10), moderate (6–8) or high (≤5) risk of bias.

Statistical analysis

Random effect models were used to calculate prevalence estimates and their 95 % CI. Results are presented by decades (before year 2000, years 2000 to 2009, and year 2010 and after). Sensitivity analyses were performed by sex, age group, macroregion and diagnostic criteria. Double arcsine transformation was used to handle distribution asymmetry related to different prevalence measures(Reference Barendregt, Doi and Lee17). Continuity correction was used for adjustment when a discrete distribution was approximated by a continuous distribution. Pooled values were then converted to prevalence. Chi-square test was used to determine differences in prevalence rates among different decades. The Cochran chi-square and I 2 tests were used to evaluate statistical heterogeneity and consistency among the studies. Values of I 2 higher than 50 % were considered an indication of high heterogeneity; however, high heterogeneity is expected in meta-analysis of prevalence studies. Statistical analyses were performed using MetaXL (Epi-Gear International, Sunrise Beach, Australia), an Excel-based comprehensive program for meta-analysis.

Results

The search retrieved 10 144 articles in 4 databases, of which 4032 were duplicates and were excluded. Additional 5099 articles were removed based on title and abstracts, and 1013 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 151 (9 187 431 individuals) met all the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

The main characteristics of the included studies are described in Table S2. Most studies had a cross-sectional design (146 studies, 97 %). Sample sizes varied substantially with a median of 1009 adolescents. Few studies collected the data before the 2000s (nine studies, 6 %). The most used criteria to define overweight or obesity were from the WHO (80 studies, 53 %).

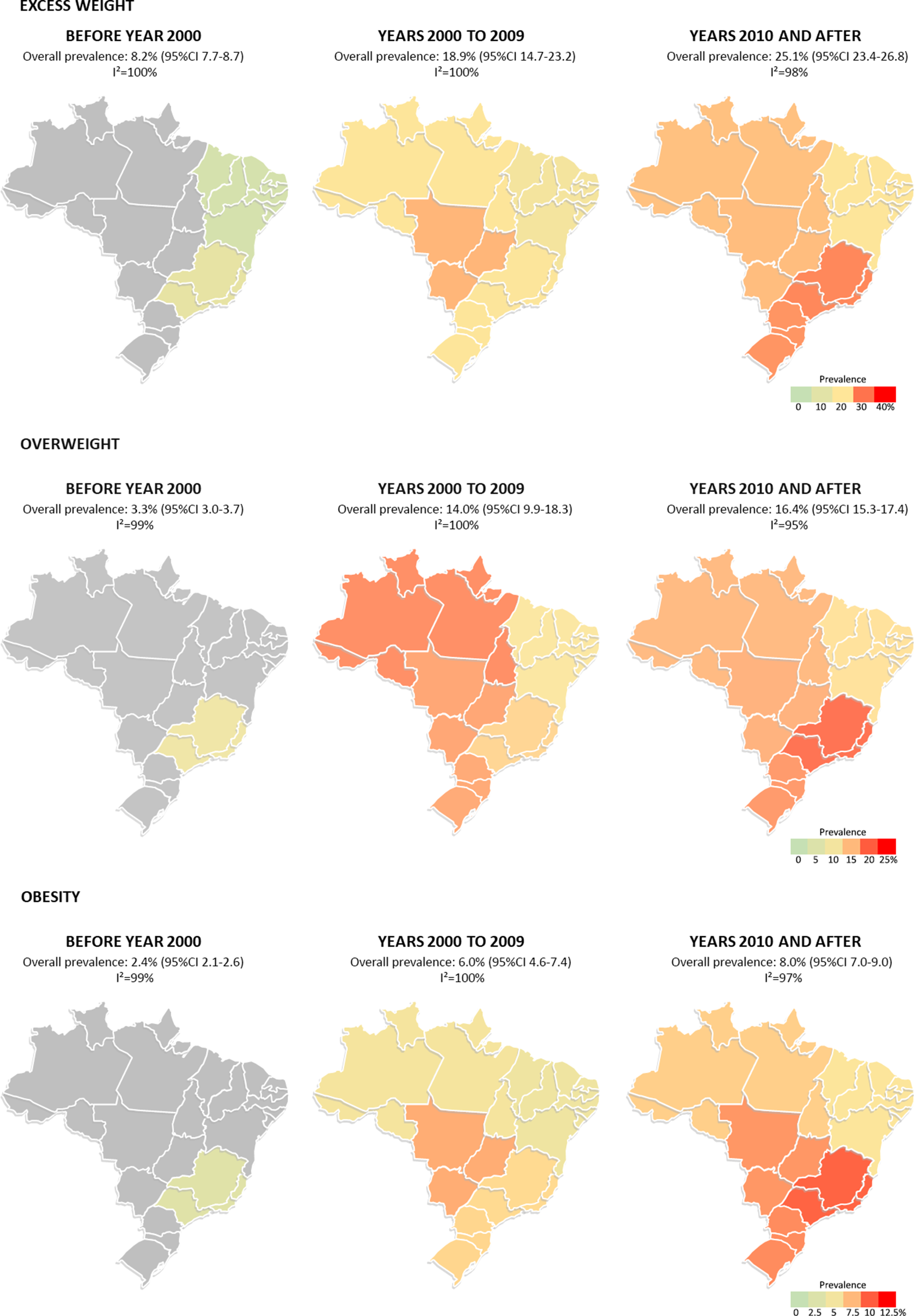

A meta-analysis was conducted according to the excess weight category and temporal trends by decades. Changes in the prevalence of excess weight over time and by Brazilian regions are shown in Fig. 2. The overall prevalence of overweight/obesity, overweight and obesity was 20·6 % (95 % CI 19·6, 21·5, I 2 100 %), 14·5 % (95 % CI 13·5, 15·4, I² 100 %) and 6·6 % (95 % CI 6·2, 7·0, I² 100 %), respectively. In trend analyses, we observed a significant increase in the prevalence of overweight/obesity in the last decades (8·2 % (95 % CI 7·7, 8·7, I² 100 %) until 2000s, 18·9 (95 % CI 14·7, 23·2, I² 100 %) in the 2000s and 25·1 % (95 % CI 23·4, 26·8, I² 98 %) in the 2010s). Similar results are observed for the trends in the prevalence of overweight and obesity when analysed separately. Complete forest plots for overweight/obesity, overweight and obesity, showing all studies included, can be found on the Online Supplementary Figs. S1, S2 and S3.

Fig. 2. Prevalence of excess weight (overweight/obesity), overweight and obesity by time period in Brazilian macroregions. Excess weight: a) Before year 2000: Northeast (n 3, 5·3 %; 95 % CI 2·5, 8·9, I² 99 %) and Southeast (n 8, 11·9 %; 95 % CI 6·5, 18·1, I² 99 %). b) Years 2000 to 2009: North (n 3, 19·4 %; 95 % CI 13·5, 25·7, I² 98 %), Northeast (n 14, 16·4 %; 95 % CI 13·9, 19·1, I² 97 %), Midwest (n 2, 24·2 %; 95 % CI 17·9, 30·9, I² 97 %), Southeast (n 27, 19·1 %; 95 % CI 16·7, 21·6, I² 98 %) and South (n 23, 19·6 %; 95 % CI 16·5, 22·9, I² 98 %). c) Years 2010 and after: North (n 5, 23·3 %; 95 % CI 21·3, 25·5, I² 82 %), Northeast (n 18, 19·6 %; 95 % CI 17·0, 22·5, I² 97 %), Midwest (n 4, 23·6 %; 95 % CI 22·2, 25·1, I² 51 %), Southeast (n 19, 28·2 %; 95 % CI 25·8, 30·6, I² 95 %) and South (n 28, 27·1 %; 95 % CI 24·2, 30·0, I² 97 %). Overweight: a) Before year 2000: Southeast (n 4, 9·0 %; 95 % CI 3·5, 15·5, I² 98 %). b) Years 2000 to 2009: North (n 2, 17·7 %; 95 % CI 9·6, 26·8, I² 97 %), Northeast (n 10, 11·7 %; 95 % CI 9·8, 13·7, I² 94 %), Midwest (n 2, 16·4 %; 95 % CI 12·8, 20·1, I² 93 %), Southeast (n 21, 13·6 %; 95 % CI 12·1, 15·2, I² 95 %) and South (n 13, 16·1 %; 95 % CI 13·9, 18·3, I² 94 %). c) Years 2010 and after: North (n 2, 15·2 %; 95 % CI 14·7, 15·8, I² 0 %), Northeast (n 14, 12·9 %; 95 % CI 11·1, 14·8, I² 94 %), Midwest (n 4, 15·6 %; 95 % CI 14·3, 17·0, I² 59 %), Southeast (n 12, 19·4 %; 95 % CI 18·1, 20·8, I² 85 %) and South (n 18, 17·1 %; 95 % CI 15·3, 19·1, I² 94 %). Obesity: a) Before year 2000: Southeast (n 3, 2·9 %; 95 % CI 1·3, 4·8, I² 90 %). b) Years 2000 to 2009: North (n 2, 5·2 %; 95 % CI 4·0, 6·5, I² 59 %), Northeast (n 10, 4·5 %; 95 % CI 2·9, 6·3, I² 97 %), Midwest (n 2, 7·8 %; 95 % CI 5·1, 10·7, I² 93 %), Southeast (n 23, 6·6 %; 95 % CI 5·2, 8·1, I² 97 %) and South (n 15, 6·7 %; 95 % CI 5·3, 8·3, I² 95 %). c) Years 2010 and after: North (n 3, 6·9 %; 95 % CI 5·8, 8·1, I² 20 %), Northeast (n 15, 6·0 %; 95 % CI 4·9, 7·2, I² 93 %), Midwest (n 5, 8·4 %; 95 % CI 7·1, 9·8, I² 79 %), Southeast (n 12, 9·8 %; 95 % CI 7·9, 11·9, I² 97 %) and South (n 19, 8·7 %; 95 % CI 6·7, 10·9, I² 98 %).

In relation to regional estimates, only the Northeast and Southeast regions had data available before year 2000 invalidating comparisons among regions at this time. Between years 2000 and 2009 and after 2010, the Northeast had the lowest prevalence of excess weight, overweight and obesity compared to the other regions. A small number of studies from the Midwest and North regions were included in the last two time periods. The highest prevalence of all weight groups in years 2010 and after was found in the Southeast region, followed by the South region (Fig. 2).

Prevalence rates of excess weight category and their 95 % CI by sex, age group and diagnostic criteria are presented in Table 1. The overall prevalence of overweight and obesity was similar among sexes, except for studies before year 2000, for which females had a higher prevalence of excess weight. Studies that enrolled older adolescents and those adopting International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) cut-off points after year 2000 reported lower prevalence ratios of excess weight compared to other categories. High statistical heterogeneity was identified in all analyses.

Table 1 Subgroup meta-analyses of excess weight, overweight and obesity by decades

IOTF, International Obesity Task Force; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Risk of bias assessment is presented in online Supplementary Table S3. Overall risk of bias was considered low in 108 studies (71·5 %), moderate in 42 studies and high in 1 study. All studies had data collected using the same mode and directly from the subjects, had an acceptable case definition, measured the parameter of interest with an instrument shown to have validity and reliability, and had appropriate numerators and denominators for the parameter of interest. Most studies selected a population that was nationally representative in the parameters of interest (66·9 %) and had a sampling frame representative of the target population (88·7 %). A census or a random form of selection was used in 115 studies (76·2 %) and the likelihood of non-response bias was minimal in 77 studies (51·0 %).

Discussion

In this systematic review, we identified 151 studies reporting rates of excess weight in Brazilian adolescents, with data collected from 1974 to 2018. Prevalence of excess weight ranged from 2·2 % to 44·4 %, and an increase could be seen when comparing information from more recent to older studies. Populations were included from household surveys, birth cohorts and school-based samples, and only twelve studies included individuals from more than one macroregion in Brazil.

Individual cross-sectional studies have hinted the rising trends of overweight and obesity among this age group in different countries(Reference Ogden, Carroll and Lawman18,Reference Wang and Lobstein19) , but representative data of trends about the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Brazilian adolescents were limited. To fill this gap, we performed a systematic review focused on adolescents from all regions in Brazil, and we show separate data by decades of data collection. In general, we observed an increase in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Brazilian adolescents since the 70s. The high statistical heterogeneity found was expected, as previous meta-analyses of prevalence studies showed(Reference Maria Aiello, Marques de Mello and Souza Nunes12,Reference Wong, Huang and Wang20) . In our analysis, the heterogeneity can be due to differences between samples of the studies in many characteristics, such as age (some included adolescents from all ages, others included only those with 10 to 13 years or 17 and older), ethnic background (some studies were made with indigenous populations), criteria for excess weight (five different classifications were observed) and type of study (school-based, household survey or cohort).

In the last decades, Brazil and other middle-income countries have experienced a quick transition in food availability and eating habits. Until recently, the most prevalent nutritional problem in Brazilian children and adolescents was underweight/undernutrition, especially in the poorer and less developed regions of the country(Reference Monteiro, Benicio and Konno21). However, due to a rapid industrial expansion and changes in lifestyle (such as increase in sedentary time(Reference Schaan, Cureau and Bloch22) and consumption of ultra-processed foods(Reference Souza, Barufaldi and Abreu23)), a double disease burden can be seen – undernutrition is still present in many areas, but obesity-related health problems are higher than ever(Reference Conde and Monteiro24). Countries like India and China, which also underwent significant socio-economic changes in a small amount of time, have similar growing trends in excess weight in youth. From the 80s to the last 10 years, for an example, overweight rates increased from 1·8 % to over 13 % in Chinese children and adolescents(Reference Yu, Han and Chu25).

In this systematic review, we present an overall prevalence of excess weight from studies that have adopted different criteria to classify adolescents with overweight and obesity, one of them specifically made using only Brazilian children(Reference Conde and Monteiro26). Classification based on the article by Must et al(Reference Must, Dallal and Dietz27) was the least used. Classification based on WHO references(Reference de Onis, Onyango and Borghi28) was the most commonly used, especially in studies published since 2009. Criteria by IOTF for overweight/obesity(Reference Cole, Bellizzi and Flegal29) was the preferred before year 2000. It is possible to consider that adding prevalence from diverse cutoffs is a limitation and could lead to imprecise results; however, the prevalence for overweight/obesity still exponentially increased in last decades when we analyze separately studies that used WHO reference curves (4.4 % until year 2000 to 26.6 % in the 2010s) and IOTF criteria (9.2 % to 21.7 %), despite including a smaller number of articles.

In subgroup analysis, the prevalence of excess weight varied greatly among macroregions, reflecting the health inequalities between them. In the literature, many studies show that associations between socio-economic status (SES) and rates of obesity depend on local characteristics – people with higher SES are less likely to be overweight or obese in high-income countries, but more likely in lower-income countries(Reference McLaren30). In a continental sized country such as Brazil, it is important to address how significant differences among regions can influence nutritional patterns. In our study, we found a positive association between SES and rates of excess weight comparing regions – prevalence was lower in the Northeast region across all decades and higher in the South and Southeast regions in the last decade. States from the Northeast region have the lowest Human Development Index (HDI) in the country, and nutritional transition at these places is relatively recent or concurrent, with underweight still being an important public health concern. Conversely, at the South and Southeast regions, comprising states that have the highest HDI of the country, these changes were observed decades ago, and ultra-processed foods are more easily accessible(Reference Conde and Monteiro24,Reference Batista Filho and Rissin31) . This dietary pattern has been previously reported in adolescents – in the ERICA study, higher SES was associated with greater consumption of unhealthy foods, such as sugary drinks and snacks(Reference de Alves, de Souza and Barufaldi32).

The prevalence of overweight/obesity in this study was similar and increased across decades in both sexes; however, girls had higher rates of excess weight before year 2000 (11·9 % v. 4·6 %). This can be partially explained due to the fact that, in this period, two big studies included only boys at older age (17–19 years) from the Brazilian Army database. Similar results by sex are observed in a recent country-wide survey in Brazil(Reference Bloch, Klein and Szklo33), supporting that prevention polices against obesity should be conducted independently of sex. Finally, analyses comparing group ages showed that younger adolescents had higher prevalence of excess weight compared to their older counterparts. This can be directly related to puberty and its effect on acquisition of fat-free mass, reaching the highest levels at peak height growth velocity(Reference de Oliveira, da Silva and Oliveira34).

Treatment of obesity in a health system usually involves recommendation of lifestyle modifications (increase physical activity, decrease sugar and fat consumption), pharmacological therapy and, in selected cases, bariatric surgery. Nevertheless, obesity rates continue to grow alarmingly worldwide. This can be attributed to the fact that the ‘pressure’ from the obesogenic environment is still the same, and therefore interventions should also try to change socio-economic, political and cultural context involving excess weight. Efforts such as clear nutritional labelling in packages or decrease in percentual of fats are commonly accepted by decision-makers and food industry. However, regulation of food advertising, taxing or banning energy-dense and nutrition-poor foods sold in schools find a barrier for implementation, mostly due to commercial interests(Reference Dias, Henriques and Anjos35). Actions for prevention of obesity during childhood also involve the same modifications in public policies. Only when obesity is approached in an interdisciplinary way beyond the health sector, we will have a real chance of altering its repercussions later in life.

Nonetheless, it is important to consider regional access to healthcare services and economical power when defining prevention strategies, as they vary greatly among Brazilian regions. Populations from the North and Northeast regions, especially those with lower SES, have more difficulty in reaching the healthcare system, and when they do, resources are scarce(Reference Uchimura, Felisberto and Fusaro36). Additionally, access to healthy foods, such as vegetables and fruits, can be limited, as they have higher prices compared to ultra-processed foods. In contrast, adolescents from the South and Southeast regions have higher prevalence of excessive screen(Reference Schaan, Cureau and Bloch22) and sitting time(Reference Werneck, Oyeyemi and Fernandes37), as well as higher access to physical education classes. These inequity patterns show that there is no simple or single solution to tackle this health problem in Brazil. Public policies need to be specific for each region, considering their strengths and weaknesses, in order to be effective. In the South and Southeast, the higher accessibility to infrastructure (sports courts, tracks and swimming pools) can be used to diminish sedentary behaviour and to promote physical activity, while in the North and Northeast it is essential to improve nutritional composition and overall access to healthcare services.

Our study has some limitations. The number of studies from before the 2000s was much smaller than those from other decades, and more than half were composed by adolescents from the Southeast region of Brazil; therefore, the prevalence from this period may not be accurate. There was also a low representation of individuals from the North and Midwest regions, especially before 2010. This poor coverage of epidemiological changes in some Brazilian regions restricts the evaluation of national prevalence of excess weight over time. Further studies in these macroregions are required to correctly demonstrate racial, cultural and socio-economic diversity of this nation. Differences and changes in diagnosis criteria over time among the studies may also limit the interpretation of our results. High heterogeneity was found in all analyses; however, this is expected when gathering results from more than a hundred studies that used multiple criteria and included individuals from different regions and age groups.

Conclusions

Despite inherent limitations from gathering data of studies from a continent-sized country such as Brazil, our findings can be considered the most recent trend estimates of excess weight in adolescents, and they clearly show that the prevalence of overweight and obesity is alarmingly increasing in recent years. This situation warrants public health interventions, which should be based mainly on prevention of overweight during the adolescence and its health consequences later in life.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: Not applicable. Financial support: This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001 and National Counsel of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq) (grant: 440822/2017–3). Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: MS, FVC, LCP and BDS conceived and designed the analysis. MS, JdAR, DSS, MMM, GZ and MRG collected the data. MS and FVC performed the analysis. All authors contributed to writing the paper. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021001464