Introduction

With the proliferation of electronic medical records (EMRs) and accompanying tools including patient portals, researchers conducting studies on human subjects are increasingly leveraging electronic methods of cohort identification, recruitment, and data collection. Failure to efficiently recruit sufficient numbers of participants is commonplace with substantial consequences, including increased trial costs and delays in generating and translating research findings [Reference Hudson, Guttmacher and Collins1–Reference Hudson, Lauer and Collins3]. Electronic methods of recruiting and administering surveys have the potential to save time and cost compared with traditional methods [Reference Bray4]. The patient portal serves as a technology platform for healthcare systems, including healthcare providers, to securely connect with patients and coordinate care, and has great potential to engage patients in research.

The mandated meaningful use criteria of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Electronic Health Record Incentive Program includes providing secure messaging between the patient and provider [Reference Wright5]. Patient portal messaging has been shown effective as a patient engagement strategy. For example, the use of patient portal messaging to communicate preventive care and appointment reminders found that it successfully decreased missed appointments and encouraged higher usage rates of preventive services [Reference Irizarry, De Vito Dabbs and Curran6]. Sending messages to patients through the patient portal allows their contact and health information to remain within the secure environment of the EMR. The patient portal can engage patients in research through notification of research opportunities, recruitment, informed consent, survey administration, and participant retention efforts such as disseminating study newsletters and results [Reference Irizarry, De Vito Dabbs and Curran6].

The limited available evidence suggests that patient portal messaging may be more effective than email, while also being cost and time efficient compared with traditional research recruitment methods. A surgical study found that there was a 14% enrollment rate using patient portal messaging recruitment, and there were similar demographics between participants recruited from both patient portal and traditional methods [Reference Baucom7]. Findings indicate that secure message reminders are most effective when they are tailored to population and context [Reference Irizarry, De Vito Dabbs and Curran6]. However, the majority of research exploring the effectiveness of patient portal as a recruitment tool was done in situations where the providers recruiting the participants had an ongoing relationship with the patients [Reference Grant8–Reference Simon10]. An institution-wide patient portal messaging recruitment service differs by allowing investigators to send patient portal messages to patients within the health system for whom the investigator is not a provider. Rigorous evaluations and comparisons of recruitment strategies are sparse [Reference Kramer, Smith and Califf11–Reference Kost13]. Examining whether patient portal messaging is an effective, cost-efficient, and well-received recruitment strategy is essential to determining whether it is worth devoting resources to employ an institution-wide patient portal messaging recruitment service.

The purpose of this paper is to describe the creation of an institution-wide patient portal messaging research recruitment service, and to report pilot results for patient satisfaction with the service and comparison of the service to traditional methods in meeting recruitment goals.

Methods

A team of data analysts, experts in research participant recruitment methods, and experienced clinical researchers collaborated to create the patient portal messaging recruitment service. By creating an institutional service, we are promoting an efficient process for studies seeking to use this recruitment method and proactively addressing concerns regarding satisfaction and privacy among patients within the health system. We have engaged key stakeholder groups including the hospital’s Patient and Family Advisory Council, health system clinicians, the Institutional Review Board (IRB), and the Center for Clinical Data Analytics in establishing the service.

Through an iterative process, the recruitment service is working closely with the IRB to develop required elements for inclusion in patient portal messages. Any patient portal message sent for research recruitment must contain (1) directions on how to opt-out of receiving future research recruitment messages, (2) directions on who to contact for more details regarding the use of patient portal for research, and (3) a link to a “Frequently Asked Questions” webpage specific to the use of patient portal messaging for research. In addition, the patient portal “Terms and Conditions” were updated to include a statement notifying patients that the portal may be used to send research messages and directions on how to opt-out of receiving these messages. Before roll-out of the service, the vice dean for clinical investigation sent an email introducing the patient portal recruitment strategy to clinicians so they would be prepared to address questions that they might receive from patients in the health system.

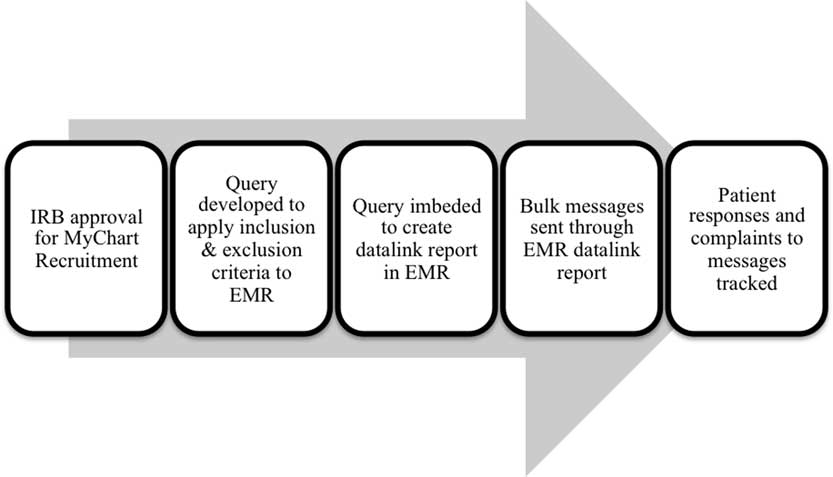

We worked with 2 study teams led by experienced principal investigators to pilot the service. The multistage process is detailed in Fig. 1. Once the studies receive IRB approval, the study team meets with the clinical data analytics team to identify eligible participants through EMRs. Together, they determine how to apply their inclusion and exclusion criteria to the available EMR data to discern eligible study participants. An iterative process is required to refine the phenotype and optimize sensitivity and specificity. The result is a computable phenotype, a Structured Language Query (SQL) code identifying the desired study population. The EMR Research Team applies the computable phenotype to the EMR (EPIC software, WI), and which results in a workbench report of patients that meet the study’s criteria. A recruitment staff member trained in human subjects research is given access to the report in the EMR and is responsible for sending bulk patient portal messages to the identified patients. Each recruitment project begins with a small sample of 250 patients to identify any problems. Following the first batch of 250 messages, study teams may contact as many as 1000 patients through bulk messaging on a biweekly basis. During the pilot phase of the service, we are administering a brief, 3-item survey to assess patient perceptions of patient portal use for research recruitment messaging.

Fig. 1 Process for patient portal messaging recruitment. IRB, Institutional Review Board; EMR, electronic medical record.

The patient portal messaging committee oversees the patient portal messaging service. The committee meets monthly and includes experts from the IRB, clinical data analysts, and EMR Research Committee. The committee collaborates with patient advocates and clinicians to ensure they are maximizing the effectiveness of patient portal messaging recruitment and minimizing any burden for patients and clinicians. Initial committee policies developed as a result of stakeholder input include: (1) one-time messaging per study, (2) limiting frequency of messages to no more than 1 in 30 days for any given patient, and (3) simple opt-out process for patients who prefer to not receive recruitment messages. This committee is responsible for overall governance of research recruitment using the patient portal, and creates and refines guidelines and policies related to the use of EMRs for recruitment.

Results of Pilot Efforts

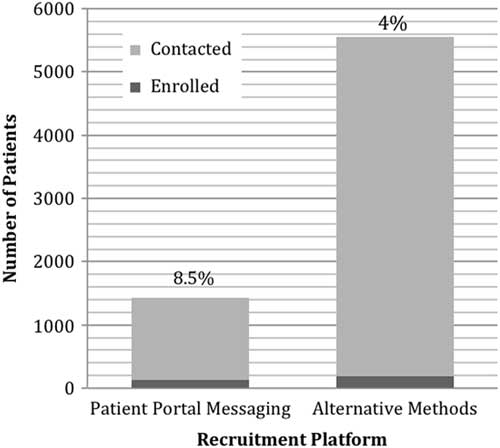

Patient portal messaging for recruitment, consent, and survey administration was piloted with a longitudinal cohort study investigating patient-reported outcomes in atrial fibrillation patients. Potential participants were identified through EMRs using a computable phenotype with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The query to identify patients in EMRs included: atrial fibrillation ICD9 and 10 codes, at least 3 nonemergency department visits within the last 4 years, age ≥18. The process for identifying and recruiting eligible patients through EMRs was developed collaboratively across the 4 academic medical centers participating in this longitudinal cohort study [Reference Amin14]. The effectiveness and patient-reported satisfaction with patient portal messaging in comparison with other recruitment methods and patient-reported satisfaction with patient portal messaging was examined. Identified potential participants were contacted with study invitations through in-clinic, email, phone, patient portal messaging and post mail techniques. Potential participants were approached in a clinic or called only after receiving a post mail or email indicating their interest in the study. Ultimately, 6666 participants were contacted, 5363 through post mail, email, telephone, or in-clinic, and 1303 through patient portal messages. The message text was identical across all platforms. Of these, 318 participants (5%) were enrolled.

Of the 5363 potential participants contacted through post mail, email, telephone, and in-clinic, 3.5% (n=191) were enrolled (Fig. 2). Patient portal messages were sent to 1303 potential participants and of those 9.7% (n=127) were enrolled in the study. In this preliminary analysis, the patient portal enrollment rate (9.7%) was significantly higher than that of email and post mail (3.5%) strategies (p<0.05). The majority of the participants recruited were White (91%), male (67%), and on average 70 years old (±10).

Fig. 2 Number and rate of participants recruited through patient portal messaging versus alternate methods.

The vast majority (91%) of patients reported that research recruitment messaging was a good use of the patient portal, and only 1% reported that it was not a good use. The majority of patients (59%) reported that receiving the recruitment message through the patient portal did not change their satisfaction with being a patient at the medical institution. A proportion of patients (40%) reported increased satisfaction with being a patient at Johns Hopkins because of the recruitment message.

Discussion

In our early experience, patient portal messaging was found to be almost twice as effective as traditional methods in recruiting and enrolling study participants. However, there are important considerations in using patient portal messaging for recruitment. The generalizability of the sample may be impacted by using the EMR which requires prior engagement with the healthcare system. The sample recruited in the atrial fibrillation study was largely White and male, though this may reflect the population in treatment for atrial fibrillation [Reference Golwala15]. In addition, patients receive patient portal messaging via personal email and therefore require an email address and basic internet proficiency. A systematic review of online survey methods in older adults determined that individuals of higher socio-economic status were more likely to be recruited [Reference Remillard16]. Racial, ethnic, and age barriers to patient portal use have been reported across multiple studies [Reference Goldzweig17, Reference Powell18]. All of these factors could potentially limit the representativeness of samples recruited using patient portals.

Efforts at increasing patient portal use have reported promising results. A recent pilot project aimed at increasing patient portal usage in patients attending an ambulatory cardiac clinic identified lack of knowledge of the health portal, patient motivation, and portal functionality and usability as themes that support patient portal utilization [Reference Shaw19]. Previous studies have addressed the challenge of older adults’ inability to use the internet by including an in-person educational intervention to teach older adults how to access and use the internet [Reference Remillard16]. Patients who are made aware of the benefits the portal can offer, as well as the convenience factor, viewed the portal more favorably [Reference Shaw19]. Providers encouraging patients and teaching patient portal use could increase uptake in patient portal utilization [Reference Wade-Vuturo, Mayberry and Osborn20]. The opportunity for hands-on learning with the patient portal increased patients’ satisfaction with the portal [Reference Shaw19]. By helping patients access the patient portal, there would be increased likelihood that researchers could reach a larger and more generalizable population for their studies. Our findings of high patient satisfaction with MyChart Recruitment are limited by response bias, individuals dissatisfied with receiving a message related to research may have been less inclined to open the message and complete the satisfaction survey. However, less than 1% of patients have reported complaints related to MyChart Recruitment messages since the service’s pilot. The small number of patient complaints are concerns over the use of patient information for research purposes.

Required resources for the patient portal messaging recruitment must be considered. Institutional leadership decided that research teams could not initiate portal research messages by themselves but had to work with a single office. We found that we needed engaged representatives from the center for clinical data analytics, the IRB, the EMR research team, and clinical investigators. The costs associated with this service include time spent by the data analysts, the EMR research team, and the staff member interacting with study teams and delivering the patient portal messages. The principal investigators and other study team members also spent considerable time working with the service to develop the optimal phenotype, receive IRB approval, and track responses and complaints to the messages. Importantly, use of the EMR for cohort discovery with the patient portal as an engagement tool is not the panacea for research recruitment. Research teams must be well-trained in effective communication and participant recruitment skills and armed with a toolkit of recruitment strategies to convert a patient’s potential interest in a study to an enrolled study participant. Since piloting, there are currently 5 studies actively recruiting through this service, and 10 studies working with the service to begin recruitment.

In conclusion, use of the patient portal for research was both effective as a research recruitment strategy and met with high patient satisfaction in pilot efforts. Developing a service for patient portal messaging required a knowledgeable, engaged team from diverse departments of the healthcare system. Resources and a high level of engagement are needed both for the service and for the studies using the service. However, research teams report the costs for recruitment through patient portal messaging are substantially less than direct mailings. The patient portal offers a novel opportunity to increase patient engagement in research.

Acknowledgments

This article was funded through a National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Award (UL1TR001079) and a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (PCORI CDRN #1306-04912) for development of the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network, known as PCORnet. K.T.G. received support from predoctoral fellowship in Interdisciplinary Training in Cardiovascular Health Research, T32 NR012704, and Predoctoral Clinical Research Training Program, TL1 TR001078.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.