1. Introduction

The theme of ‘heritage at risk’ in this volume offers a chance to evaluate the word ‘risk’ in relation to museums. ‘Risk’ is here intended to refer to the safety of artefacts and, directly connected to this, the need for the cataloguing of finds. The safety of the finds is determined by the quality of the buildings housing them. The historic buildings in which these museums are housed represent architectural and urban value in their own right: the Castle of Tripoli, which has hosted the Archaeological Museum in the Libyan capital ever since the years of the governorship of Pietro Badoglio; the Governor's Palace, now the seat of the Museum of Libya; the Museum of Sabratha, an exemplary expression of modernist architecture of the 1930s; and the Museum of Zliten, despite the alterations to its interior following its conversion from a hotel into a museum (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Zliten Museum, 2011. Photo: D. Baldoni, Missione Archeologica Roma Tre.

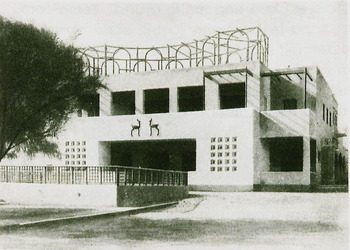

Figure 2. Zliten, Albergo alle Gazzelle, c. 1938. From La Libia, Ente Turistico Alberghiero della Libia, 1938.

At the moment all the museums and their contents have been protected. This is the result of a process that began in 2011, during the autumn months of that year which resulted in the toppling of Colonel Gaddafi's regime. In December 2011, the Department of Archaeology at Lepcis Magna and the Archaeological Mission of the University of Roma Tre carried out a survey of the museums of eastern Tripolitania: Lepcis (Figure 3), Zliten, Misurata, Madinat as-Sultan (Figure 4), and Bani Walid (Figure 5). The purpose of the survey was to assess the overall condition of the buildings, the state of conservation of the artefacts housed in them, and any loss or destruction caused by the recent conflict. A necessary corollary of this assessment was the development of a database for the finds preserved in the public collections inspected. For this purpose, all artefacts were individually photographed and summarily catalogued; so far 3,231 objects have been catalogued.

Figure 3. Lepcis Magna Museum, 2011: emptied showcases. Photo: F. Baroni, Missione Archeologica Roma Tre.

Figure 4. Madinat as-Sultan Museum: stockpiling of weapons, 2011. The exhibition room has been emptied and used as a depot for munitions. Photo: F. Baroni, Missione Archeologica Roma Tre.

Figure 5. Bani Walid Museum, 2011. Photo: Archaeological Department of Lepcis Magna.

This survey highlighted the need to begin the systematic digitisation of the cultural heritage of Libyan museums, even if limited for the time being to Tripolitania, although in a second phase the digitisation will have to be extended onto a national scale. An important contribution to these problems was the holding of a workshop in Tripoli in 2013, titled ‘Libyan Heritage in the Digital Age: The First Step’, coordinated by Hafed Walda. It was in its aftermath that the ‘Red Castle and Museums of Tripolitania’ project took shape, thanks to the cooperation of the Department of Antiquities (DoA) and the support of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The project was formalised in the same year. It focused on the cataloguing and digital storage of archaeological artefacts present in Libyan museums and archival documents.

2. The project

The project includes a trilingual database (Arabic/Italian/English) which allows the cataloguing of the various types of objects through a single interface. It can be used for any type of material and it can include objects, graphic documents and photographs in a single file. If the data in our possession permits the geo-location of finds, we can then ‘link’ an object or a document to a particular physical space/context, which we can visualise on a cartographic or satellite support. In this way the finds can be firmly tied to their site of provenance and correlated with all data relating to their discovery, excavation, conservation and display.

The programme allows the acquisition of a wide range of archival material: registers and inventories, reports on the activities of ancient monuments commissions, topographical maps, surveys, drawings and photographs, largely produced between the 1920s and 1970s. All this archival material can be firmly linked to the material contexts to which they refer. This will facilitate access to the historic archaeological documentation that is actually held not only in the archive of the DoA, but also in large part preserved in Italian archives and institutions, not always easy to access.

For the time being the pilot project is limited to the sole macro-area of Tripolitania. However, the individual components are transferable to other areas. This will permit the data to be exported through widely used formats and inserted in a more complex and binding nation-wide programme. Such an enlarged programme represents, clearly, a huge commitment, which would need to be tackled with other entities and with other resources surmounting our present capacities. As things stand today, the system can produce a data file corresponding to the characteristics requested by the protocol Object ID now in use in the main international institutions responsible for the crackdown on the illicit trade in works of art. This was also discussed in the ‘Current Status of Archaeological Sites, Monuments and Museums’ section of the workshop recently held in Rome (29 February–2 March 2016), organised by Susan Kane, in a perspective aimed at managing the risk as well as controlling theft, in close coordination with the FBI Art Crime Team and the equivalent Italian agency, the Nucleo Tutela Patrimonio Culturale dell'Arma dei Carabinieri.

3. The Museum of Bani Walid

Considering specifically the issue of materials under threat, the focus of the present paper will be on the Museum of Bani Walid. Due to the uniqueness of the materials it contains, it deserves a ‘special’ intervention with a view to its renovation and promotion as a cultural hub in the region. This should be combined with a systematic study of the finds ‘quarried’ from mausolea scattered over the huge territory of which Bani Walid, capital of the Warfalla region in south-east Tripolitania, represents the largest inhabited centre. The territory comprises the basin of the Wadi Soffegin and its extensive network of tributaries, stretching eastward as far as the valley of the Wadi Zem-Zem. Between 1979 and 1989 this territory was the focus of the ambitious UNESCO Libyan Valleys Archaeological Survey project.

If the years of the Jamahiriyya generally appear characterised by an atmosphere of lukewarm interest shown by the regime towards the conservation of the country's archaeological heritage, in Bani Walid the opposite was the case. The express wish of the then president of the Department of Antiquities of Libya, Ali Emhemmed al-Khadduri, a local man and very close to the Colonel, was to create a museum at Bani Walid that would champion the values of the territory: a museum able to promote and defend the culture of the local populations, who may have been absorbed into the Roman orbit, but whose native individuality and identity are still clearly recognisable. The museum was created between 1988 and 1991. It was installed in a one-storey building originally built as a school, presumably in the second half of the last century. It consists of eleven exhibition rooms and a gallery, which surrounds three sides of the large courtyard. In 2011 the museum was the scene of gun battles between loyalist troops, who had occupied it, and rebels. Damage was caused both to the building and to the collections (Figures 6–8). The objects displayed in the glass cases suffered the worst damage: they were vandalised (Figure 9), destroyed (Figure 10), or looted (in particular coins and oil-lamps). Structural damage was caused by gunfire to the upper part of the mausoleum reconstructed at the centre of the courtyard (Figure 11). In 2016, thanks to the financial support of the community of Bani Walid, the structure has been rehabilitated and most of the artefacts restored to their original location (Figures 12–14).

Figure 6. Bani Walid Museum, 2011. Photo: D. Baldoni, Missione Archeologica Roma Tre.

Figure 7. Bani Walid Museum, 2011. Photo: D. Baldoni, Missione Archeologica Roma Tre.

Figure 8. Bani Walid Museum, 2011. Photo: Archaeological Department of Lepcis Magna.

Figure 9. Bani Walid Museum, 2011. Photo: F. Baroni, Missione Archeologica Roma Tre.

Figure 10. Bani Walid Museum, 2011. Photo: Archaeological Department of Lepcis Magna.

Figure 11. Bani Walid Museum, 2011. Photo: Archaeological Department of Lepcis Magna.

Figure 12. Bani Walid Museum, 2016, after refurbishing. Photo: Musbah Abdulhafiz Musbah, Bani Walid Museum.

Figure 13. Bani Walid Museum, 2016, after refurbishing. Photo: Musbah Abdulhafiz Musbah, Bani Walid Museum.

Figure 14. Bani Walid Museum, 2016, after refurbishing. Photo: Musbah Abdulhafiz Musbah, Bani Walid Museum.

The abundance of figurative decoration – mainly from the mausolea – present in the territory of Bani Walid has been known ever since the early years of the nineteenth century. This is well documented by the account that the future admiral William Henry Smyth wrote of his stay at Bani Walid, on 3 March 1817, along the route that would lead him to Ghirza. To quote Smyth's own words:

Having found several people here who had recently arrived from the place I was bound to, I repeated my inquiries respecting the sculpture, and again received positive assurances that I should see figures of men, women, children, camels, horses, ostriches, &c., in perfect preservation; and the belief of their being petrifactions was so prevalent, that doubts were expressed whether I should be able to remove any one of those whom it had pleased Providence thus to punish for their sins. (Smyth, quoted in Beechey and Beechey Reference Beechey and Beechey1828, 504–12, particularly 507–508).

The rich archaeological heritage of the area is also demonstrated by the considerable amount of architectural material collected in the Italian fort at Bani Walid during the colonial occupation; it was documented by John Ward-Perkins in 1948. In the 1950s the collection was transferred by the Superintendent Ernesto Vergara Caffarelli to Tripoli with the aim of re-organising the Archaeological Museum display; later a large part of the material was shipped to Lepcis Magna and put on display in the new museum, inaugurated in 1994.

At the moment, the collection displayed in the museum is composed of a large quantity of materials gathered throughout the Warfalla territory. Some of it, such as the elements of architectural decoration from Ghirza, the inscription from the mausoleum of Gasr Banat, the relief of mourners from the mausoleum of Wadi Migdal (Figure 15) are well known. When removal of the material proved impossible, recourse was had to plaster casts (for example, the frieze of the tomb of Wadi Umm el-Agerem, or the relief of the North A mausoleum at Ghirza). More importantly, however, the creation of the museum proceeded side by side with a new survey of the territory. This survey was coordinated by Dr. Mahmud el-Nemsi, at the time in the service of the Department of Antiquities at Lepcis Magna, who transferred many unpublished items to the museum. The report and photographic documentation of the reconnaissance are of great value to identify the provenance of artefacts.

Figure 15. Bani Walid Museum. Relief illustrating four mourning women, from the mausoleum of Wadi Migdal. Photo: F. Baroni, Missione Archeologica Roma Tre.

The aim of the organisers of the museum was to offer a comprehensive cultural survey of the region. However, the task was complicated by the lack of documentation relating to grave goods (all the burial chambers of the mausolea showed signs of looting). It was therefore decided to transfer to the museum some tomb furnishings from other collections – such as cinerary urns in stone and glass, amphorae intended to contain the remains of the funeral pyre, tableware in pottery and glass, oil-lamps and coins (‘Charon's obol’). These were brought from the storerooms both of Lepcis Magna and of the Museum of Tripoli.

The core of the collection is composed of hundreds of architectural fragments from the many mausolea that punctuated the course of the great widian. In some cases, they are accompanied by inscriptions with the names of the founder(s) of the tomb and his family. Other fragments consist of capitals, columns, bases, friezes, often with vegetal ornamentation, some with metope decoration, some with a continuous frieze, some with figures. Among them, we may mention some friezes from the mausoleum of Wadi al-Bneya, with decorative motifs linked to agriculture, hunting (with the use of the net), and combats between men and wild animals; this latter iconography has very precise affinities with the frieze of mausoleum North B at Ghirza.

4. The territory of Bani Walid

It is interesting to cite two of the better preserved mausolea in the territory as examples. They have both been dated by Ginette Di Vita-Evrard to between the middle and second half of the second century AD, on the basis of their respective inscriptions. Of the first, located at Wadi Ghalbun, some four kilometres NW of Bani Walid, only the upper storey is preserved. Conspicuous portions of its figural decoration, including the prominent figure of Hercules, are still visible. The text of the inscription, written in Latin characters but in the neo-Punic language, was subjected to a brief analysis by Robert Kerr (Reference Kerr2010): of special interest is the presence of the Latin technical loanword procurator. The second monument comes from Wadi Khanafes. Its upper storey has been reconstructed. The statue of the founder of the tomb is prominently displayed in its upper niche: his dress, attributes (rotulus), hairstyle and cut of his beard (his face is largely a modern reconstruction) are all elements that declare the patron's wish to be portrayed in the habitus of a Roman citizen, even if he did not have that status (Figures 16–17). The lower storey of the mausoleum is characterised by the funerary door surmounted by a fragmentary four-line Latino-Punic dedicatory inscription within a tabula ansata. It reads: ‘Mausoleum, which was made by Pudens / and Severus for their father Amsua/la, son of Masuna for 1700 [denari i] / and the architect who made [it] was Reginus who …’. So the inscription tells us that the monument was erected at the expense of two brothers for their father, whose patronymic is cited. Father and grandfather bear Libyan names, while the sons each received a single Latin name (they were not Roman citizens), respectively Pudens and Severus, both names particularly loved by the Africans. The architect of the tomb, Reginus, also bears a Latin name. During this period, fictitious integration into the onomastic system must have assumed a strong self-representative significance for these ‘notables of the desert’; however, this concept would gradually decline in a later period, in a radically changed social climate.

Figure 16. Bani Walid Museum. The Mausoleum of Wadi Khanafes, upper storey. Photo: F. Baroni, Missione Archeologica Roma Tre.

Figure 17. Bani Walid Museum. The Mausoleum of Wadi Khanafes, upper storey, present state. Photo: Musbah Abdulhafiz Musbah, Bani Walid Museum.

The ‘funerary system’ has its most spectacular monumental manifestation and bears its most potent ideological message in the mausolea. They indicate considerable economic potential; they are a staging of family values; they reflect the social structure of the ruling class that commissioned them. The figurative paradigm and the codes of communication need to be further elucidated in the ongoing debate on the identity features of pre-desert culture, torn between originality, innovation and acculturation, and conditioned by the need for the families that commissioned these tombs to display their own status and power.

5. Future work at Bani Walid

At Bani Walid there is still a great deal to do. Thanks to an agreement with the DoA, a teamwork plan involving various skills has been organised: it comprises the study of the architectural decoration, that of the inscriptions, and the restoration, where possible, of the monuments. But above all it is a work of cooperation of our Libyan colleagues: without their active participation it would be impossible to proceed to the documentation and study of the materials or that of the provenance of the finds. We hope at the same time to formalise a collaboration with our colleagues who are involved in the reorganisation and study of the archive collected in the Society for Libyan Studies, hosted at the University of Leicester, currently in a phase of digitisation. This important sharing of tasks represents the only viable way to achieve an exhaustive archive of the sites and materials of the pre-desert area.