In response to increased biodiversity loss (Ceballos et al., Reference Ceballos, Ehrlich, Barnosky, Garcia, Pringle and Palmer2015), international conventions and plans, such as the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC, 2008), have been established. One of the main goals of conservation is the maintenance of ecosystems, communities, habitats and the species within them (Soulé, Reference Soulé1987). Habitat loss, however, is a significant threat to biodiversity, especially for species with restricted geographical distributions such as narrowly endemic species, which usually have specific habitat requirements (Essl et al., Reference Essl, Staudinger, Stöhr, Schratt-Ehrendorfer, Rabitsch and Niklfeld2009).

Most Brazilian species of Begonia are endemic to the country, mainly to the highly diverse and threatened Atlantic Forest (Jacques & Gregório, Reference Jacques and Gregório2020). As a result of historical loss and fragmentation of natural habitats, the Atlantic Forest is one of the so-called hottest global hotspots (Laurance, Reference Laurance2009; Rezende et al., Reference Rezende, Scarano, Assad, Joly, Metzger, Strassburg and Tabarelli2018), and protected areas are critical for the conservation of the remaining fragments of this forest. The first protected area in Brazil, Itatiaia National Park, was founded in 1937 in an important centre of endemism in the Atlantic Forest, the Mantiqueira Mountain Range (Fiaschi & Pirani, Reference Fiaschi and Pirani2009). The Park is an IUCN (1994) category II protected area, which allows public visitation.

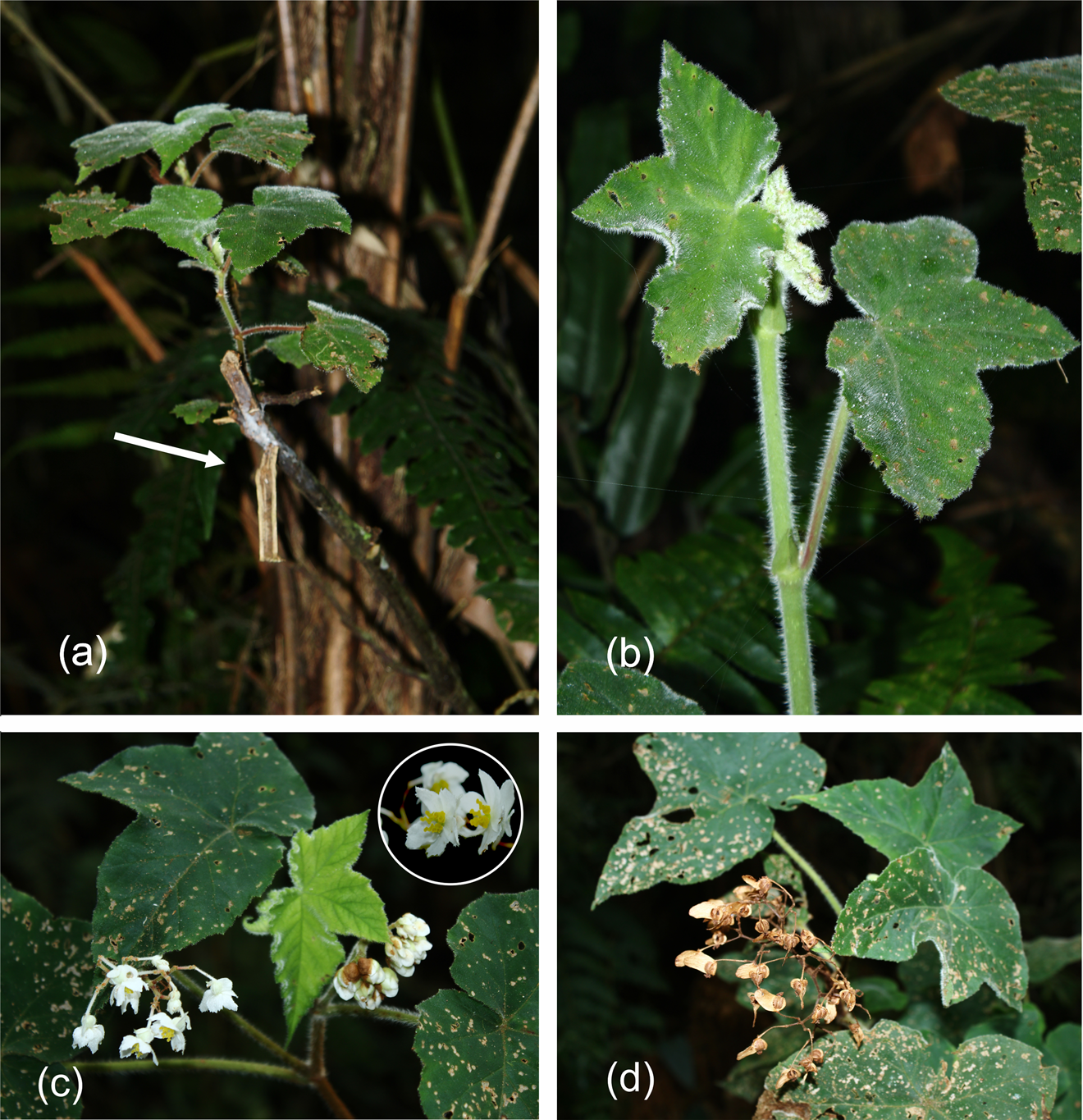

Itatiaia National Park contains 13.5% (25) of the Begonia species known from the Atlantic Forest and 29% of the Begonia species known from Rio de Janeiro state (Jacques & Gregório, Reference Jacques and Gregório2020). Begonia jocelinoi (Plate 1) is endemic to the Park and was formerly categorized as Wanted in the Red List of the Endemic Flora of Rio de Janeiro state as the species had not been recorded since 1953 (Rosa et al., Reference Rosa, Baez, Moraes, Martins, Moraes, Maurenza, Negrão, Martinelli, Martins, Moraes, Loyola and Amaro2018). Until now, B. jocelinoi was only known from herbarium specimens: the first collection was in the Park in 1943 (J.J. Sampaio 09, holotype RB, isotypes CEPEC, NY, SP; E. Pereira 324, paratypes RB), which appear in the protologue of specimen A.C. Brade 21228, paratype MBML, RB, in 1953.

Plate 1 (a) An adult Begonia jocelinoi that has been pruned (arrow) and that is sprouting, (b) a young plant, (c) adult plants at the reproductive stage, with female flowers, and (d) adult fruiting.

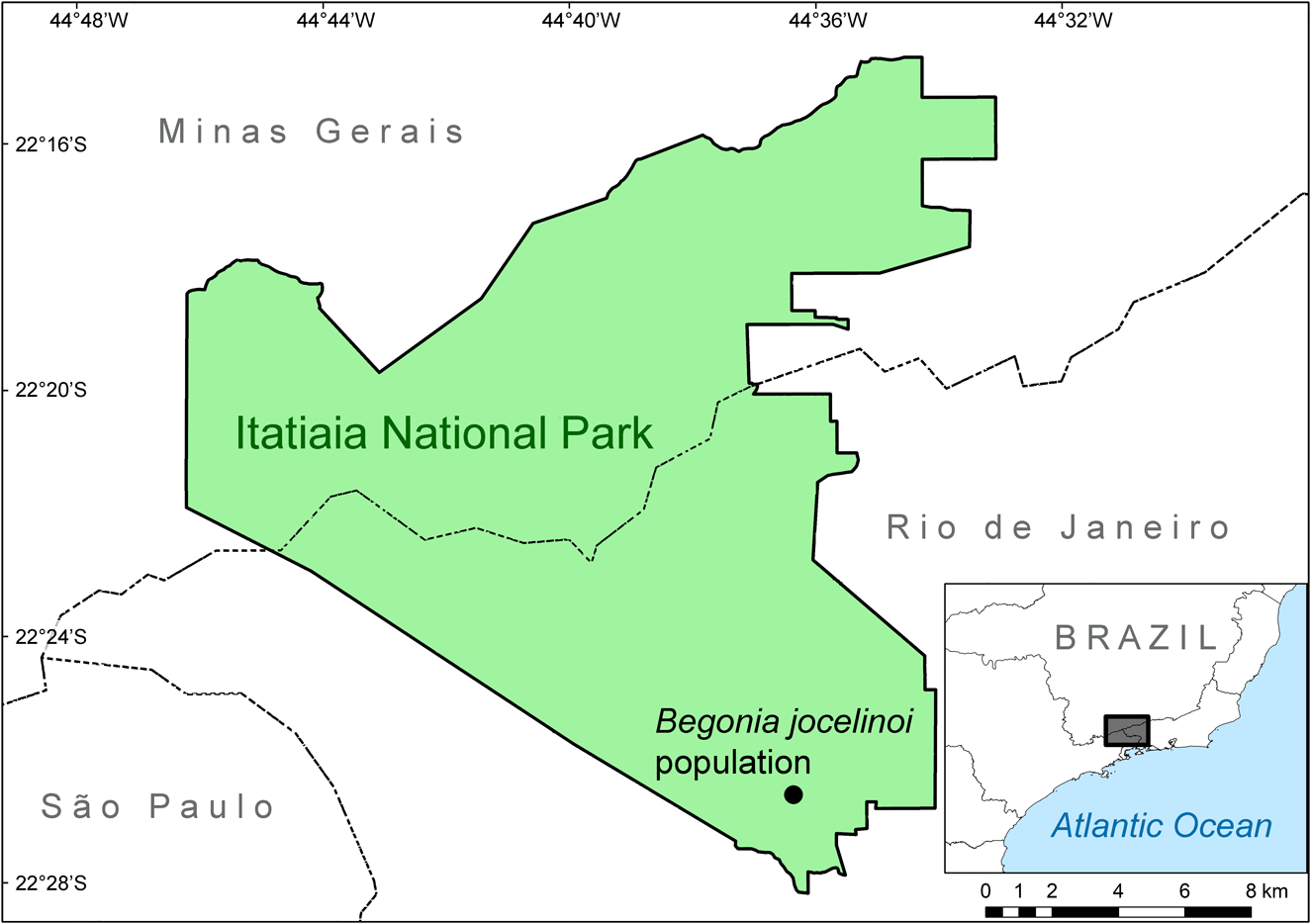

To obtain information on B. jocelinoi we consulted JABOT (2019), Specieslink (2020), and herbarium collections at RB and SPF. We visited Itatiaia National Park four times during May 2019–February 2020 to search for B. jocelinoi. Previous records of B. jocelinoi were at 1,000–1,500 m altitude and therefore we explored trails close to the type collection site and other similar trails up to c. 2,000 m altitude (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 The location of the single known population of Begonia jocelinoi in Itatiaia National Park, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

We located a single population of B. jocelinoi with 65 individuals at the reproductive stage and several hundred seedlings in five localities over 1,123–1,532 m on the Três Picos trail. The individuals at the reproductive stage had flower buds, flowers and/or fruits. Fruits had well-formed seeds, but we did not test viability. The location is shaded, with high humidity and diffuse sunlight. Some individuals were in a clearing resulting from the death of the native bamboo Guadua tagoara (Nees) Kunth following synchronous flowering.

We also located additional collections of B. jocelinoi in herbaria, all of them from the Três Picos trail: M.L.O. Trovó 510 (RB) collected in 2012, J. Luber 421 (RB), I. Paglia 31 and 72 (RB) and C. Baez 1876 (RB) collected in 2019. Other specimens that we found identified as B. jocelinoi on Specieslink are in fact Begonia convolvulacea (Klotzsch) A.DC. Begonia jocelinoi was previously categorized as Critically Endangered based on criteria B2ab-i, ii, iii (Jacques et al., Reference Jacques, Moraes, Amaro, Moraes, Amorim, Wimmer, Martinelli, Martins, Moraes, Loyola and Amaro2018). Our findings support this categorization, but based on criteria B1a + C2aii (IUCN 2012), because of its restricted geographical range (extent of occurrence 1.5 km2, area of occurrence 16.0 km2), and small population size with few mature individuals.

Few studies have directly examined the impacts of tourism on rare and threatened plants and how this may affect the risk of extinction in protected areas. Direct threats of tourism include collection of plants by tourists, maintenance of trails and damage from activities such as walking, biking and vehicles (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Pickering and Buckley2003). A typical maintenance activity in Brazilian protected areas is clearing trails to keep them open for walkers. This maintenance occurs recurrently on the Três Picos trail, and led on at least one occasion to the inadvertent pruning of B. jocelinoi (Plate 1a), including of flowering individuals. A reduced number of reproductive individuals in an isolated population can decrease genetic diversity via inbreeding and genetic drift caused by low gene flow and a small effective size (Barrett & Kohn, Reference Barrett, Kohn, Falk and Holsinger1991).

Our research in Itatiaia National Park indicates the vulnerability of B. jocelinoi as its single known population lies on a trail in a severely fragmented biome. The Atlantic Forest has the largest number of Alliance for Zero Extinction sites among Brazilian biomes (Diniz et al., Reference Diniz, Gonçalves and Brito2017). Based on the concepts of irreplaceability and vulnerability (Margules & Pressey, Reference Margules and Pressey2000), the rediscovery of a population of B. jocelinoi indicates the need to prioritize this area for local conservation. Of 16 additional threatened species in the Park that were recorded only once prior to 1969, six were recorded during 2019–2020 (Moreira et al., Reference Moreira, Carrijo, Alves-Araújo, Amorim, Rapini and Silva2020) but 10 have yet to be relocated.

Narrowly endemic species may be best conserved by local conservation efforts (Crain et al., Reference Crain, Sánchez-Cuervo, White and Steinberg2015). For this reason, we recommend the following actions for B. jocelinoi: (1) an in situ conservation plan, including studies on phenology, pollination, seed dispersal and population dynamics; (2) an ex situ conservation plan for greenhouse cultivation and to foster ornamental use; (3) advice for tourists about threatened plant species on trails and awareness of the improper collection of plants; (4) diversion of the part of the Três Picos trail where the population is located, to minimize the effects of tourism and pruning; (5) mapping other potential areas of occurrence of this species; (6) fieldwork to search for other populations in any potential areas identified. These strategies have already been proposed or are in use for the conservation of other species with a highly restricted distribution (e.g. Martinelli et al., Reference Martinell, López-Pujol, Blanché, Molero and Sàez2011; De Lírio et al., Reference De Lírio, Freitas, Negrão, Martinelli and Peixoto2018; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zhou, Liu, Mo, Zhang, Wang and Shen2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior for graduate scholarships to IP (88887.335096/2019-00) and JL (88882.447055/2019-01), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico–Bolsa de Produtividade em Pesquisa and Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro–Cientista do Nosso Estado for research grants to LF and VFM, the curators of herbaria RB and SPF for access to collections, Rafael da Silva Ribeiro for the help with the map, and Itatiaia National Park staff for logistical support and encouragement.

Author contributions

Data collection, species identification, figure preparation: IP, JL; writing: all authors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.