Suicide and attempts are prevalent among psychiatric patients and constitute a major global, clinical and public health concern. The risks are particularly high with major mood disorders, especially with bipolar disorder (BD) and severe major depressive disorder (MDD).Reference Harris and Barraclough1–Reference Tondo, Pompili, Forte and Baldessarini5 Suicide has been associated with various ‘risk factors’, as reviewed in the Supplementary Information available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.167. Despite the substantial literature on risk factors for suicide, there are surprisingly few direct comparisons of factors across patients with mood disorders evaluated under the same conditions. Clarifying risk factors for individual types of major affective disorders should enhance earlier identification of suicidal risk, support preventive interventions and improve the treatment and prognosis of patients at risk. Accordingly, this study aimed to compare demographic and clinical risk factors in large samples of patients diagnosed with MDD or type I or II BD. We hypothesised that both rates and associated risk factors would differ by diagnosis, especially between patients diagnosed with BD versus MDD.

Method

Clinical assessments

The study sample included patients with diagnoses (updated to meet DSM-5 [2013] criteria) of BD type I (BD-I), BD type II (BD-II) or major depressive (MDD) disorder at the Lucio Bini Mood Disorders Center in Cagliari, Sardinia. Included participants had repeated assessments of clinical history and of suicidal behaviour (attempts or suicides) or reported suicidal ideation over several years of follow-up. Suicide attempt included any self-injurious act, with or without evidence of intent to die; violent acts included severe self-injury with medical intervention or death, or the involvement of gunshot, hanging, drowning or asphyxiation or jumping from height. All participants underwent systematic initial and repeated diagnostic and follow-up assessments by the same mood disorders expert (L.T.). Clinical information concerning demographic, descriptive and clinical characteristics – including prospectively evaluated morbidity over time, characteristics of suicidal behaviours and treatments given – was derived from semi-structured interviews and life charts constructed at intake and updated during prospective, clinical follow-up (weekly through an index episode of illness at intake and at 1- to 6-monthly intervals thereafter, as indicated clinically). Clinical data were recorded systematically, converted to a digitised summary form from 2000 and data in computerised records were coded to protect patient identity – all as detailed previously.Reference Tondo, Lepri and Baldessarini6–Reference Tondo, Vázquez, Pinna, Vaccotto and Baldessarini9 Participants provided voluntary, written informed consent at clinic entry for the collection and analysis of data to be presented anonymously in aggregate form. This is in accordance with the requirements of Italian law, which states that a specific authorisation from local ethical committees is not required when data are anonymous, aggregated and identified by individual codes.10 Data management also complied with the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act which pertains to confidentiality of patient records.

Data analysis

Data are presented as means with 95% confidence intervals or proportions (percentage) and rates (percentage per year). Preliminary tests of association used standard bivariate comparisons based on analysis of variance methods (t-score) for continuous data and contingency tables (χ2) for categorical data. We evaluated relative risk ratios for prevalence or magnitude of each tested factor for association with suicidal status, overall and for BD versus MDD. The resulting P-values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons to guide the selection of factors for multivariable logistic modelling which generated odds ratios and their confidence intervals and χ2 values. Factors supported by logistic regression modelling were included in receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses of Bayesian sensitivity (true positive rate) versus (100 − specificity) (false positive rate) to compute the area under the curve (AUC) as a percentage. Analyses used the following commercial software: Statview version 5 for Mac (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for spreadsheets and Stata version 13 for Mac (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for analyses.

Results

Sample and exposures times

The study sample included 3284 patients with one of the following DSM-5 major mood disorders: BD-I (n = 714), BD-II (n = 497), all BD (n = 1211) or unipolar MDD (n = 2073). The duration of illness averaged 17.0 years with BD and 11.7 years with MDD (Table 1); 64.4% were women. Participants were followed prospectively at the study site for an overall average of 2.95 (95% CI 2.74–3.16) years.

Table 1 Types of suicidal risks in 3284 patients with bipolar disorder type I, bipolar disorder type II or unipolar major depressive disorder

Lifetime prevalence in patients with bipolar disorder (BD, type I or II) or major depressive disorder (MDD) compared as relative risk ratios (with χ2). Exposure years are compared by analysis of variance (t-score) and exposure-adjusted rates (percentage/year) are compared as incidence rate ratios (IRRs, with exact P-values). BD-I, BD type I; BD-II, BD type II.

a Prevalence of violent acts is expressed as proportion of all suicidal acts (attempts + suicides).

Suicidal risks

The lifetime risk (percentage of patients) of identified suicidal ideation was significantly greater among patients with BD-II (35.0%) than those with BD-I (25.2%), and among patients with BD (29.2%) than those with MDD (17.3%), as were the respective annualised rates (1.92 v. 1.55%/year and 1.72 v. 1.47%/year; Table 1). The lifetime risk of suicide attempts was non-significantly higher among participants with BD-I (20.9%) than those with BD-II (15.9%); but this risk was significantly 3.93-times greater among all patients with BD (18.8%) than those with MDD (4.78%). The exposure time-adjusted attempt rates (percentage per year) were higher in those with BD-I versus BD-II (1.28 for BD-I v. 0.88 for BD-II, 1.45-fold higher; and 1.11 for BD-I v. 0.41 for BD-II, 2.72-fold higher) and for those with BD versus MDD (Table 1). The risks and rates of suicide were similar between those with BD-I (1.82%; 0.11%/year) and BD-II (1.61%; 0.09%/year), but significantly greater with those with BD overall (1.73%; 0.10%/year) than those with MDD (0.48%; 0.04%/year). In terms of the risks and rates for all suicidal acts (attempts + suicides), patients with BD-I (22.7%; 1.39%/year) had the highest rates, followed by those with BD-II (17.5%; 0.97%/year) and then by those with MDD (5.26%; 0.45%/year); these rates were high for patients with BD overall (20.5%; 1.21%/year).

The attempts/suicides ratio of rates (%/year), a proposed measure of lethality (greater lethality with lower ratio), indicated similar lethality among all diagnostic groups: BD-II (9.78), MDD (10.2), BD-I (11.6) and all BD (11.1; Table 1). The proportion of violent attempts or suicides (involving gunshot, jumping, hanging, drowning or asphyxiation) of all suicidal acts was greater among patients with BD-I than those with BD-II (38.2 v. 23.0%), and not significantly greater in patients with BD versus those with MDD (33.1 v. 23.9%). In addition, as expected, violent acts were more prevalent among men by 1.66-fold (40.8%, 95% CI 32.2–49.7) versus women (24.6%, 19.2–30.6, χ2=10.4, P = 0.001) in both BD and MDD (not shown).

Factors associated with suicidal acts overall

Among all patients with mood disorders, the factors that were present before intake at the study site and that were significantly associated with lifetime suicidal acts (Table 2A) included: family history of major affective disorder, BD or suicide; being unmarried or divorced and having fewer children; being unemployed and having a low socioeconomic status; having experienced early abuse or trauma, and relatively early loss of a parent; being younger at illness onset and with more years at risk; having had more than four prior depressions; and being admitted to hospital for psychiatric illness.

Table 2 Factors associated with suicidal acts in 3284 patients with mood disorders

Comparisons are of proportions or values of measures among patients with versus those without suicidal behaviour (attempts or suicides); those without suicidal acts include patients with suicidal ideation only. Factors not significantly associated with suicidal behaviour included: education beyond high school, and having an anxious and hyperthymic temperament. MDD, major depressive disorder; BD, bipolar disorder; BD-I, BD type I; BD-II, BD type II; ASRS-A, Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale Part A; TEMPS-A, Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa, Paris and San Diego-Autoquestionnaire; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MDQ, Mood Disorder Questionnaire.

a. In suicidal women versus men.

b. Versus single or in long-term relationship.

c. Versus married/widowed.

d. Excludes students, homemakers, people who are disabled.

e. In low or medium versus high socioeconomic status.

f. In BD versus MDD.

g. In BD-I versus BD-II.

At intake assessment, the factors associated with lifetime risk of suicidal acts (Table 2B) included: older current age; BD (BD-I > BD-II) versus MDD diagnosis; co-occurring attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), especially with inattention (higher Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale Part A score); misuse of drugs or alcohol or smoking; lack of an anxiety disorder; mixed (hypomanic) symptoms in depressive episodes (in MDD or BD); switching into (hypo)mania in BD-I; higher ratings for dysthymic, cyclothymic or irritable temperament (Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa, Paris and San Diego-Autoquestionnaire ratings); somewhat higher Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) ratings; and higher ratings of lifetime BD-like symptoms (Mood Disorder Questionnaire score).

The factors associated with suicidal behaviour that were evaluated prospectively during follow-up (Table 2C) included: longer exposure time (years at risk), greater morbidity (as percentage time spent ill, depressed, or [hypo]manic) and psychiatric admission to hospital. In addition, although treatments were assigned clinically, it is noteworthy that antidepressant monotherapy was much less often given to patients who were suicidal, whereas use of mood stabilisers or antipsychotic drugs alone or with antidepressants was much more prevalent among patients who were suicidal (Table 2C).

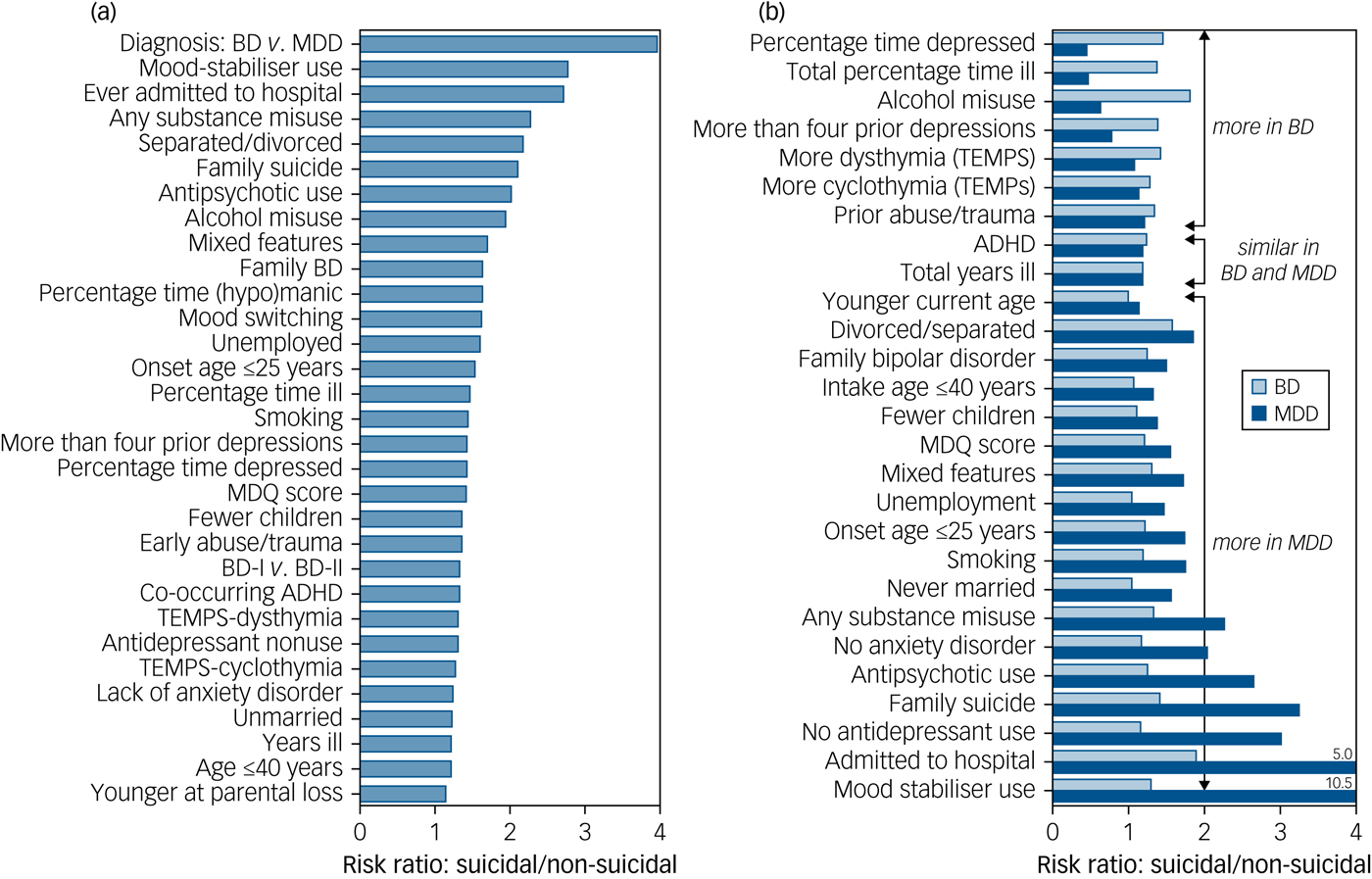

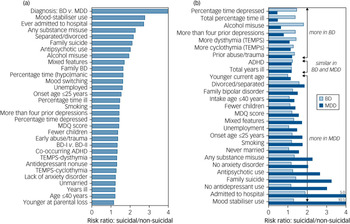

The risk factors that were most strongly associated with suicidal behaviour among the 3284 patients with major mood disorders (based on findings in Table 2) are shown in descending rank order in Fig. 1a. Additionally, associations (risk ratio) with suicidal behaviour among patients with BD and those with MDD are shown separately in Fig. 1b. Risk factors fell into three clusters: (a) those more associated with suicidal acts in patients with BD than those with MDD, (b) those similar in patients with BD and those with MDD, and (c) those more strongly associated among patients with MDD than those with BD.

Fig. 1 Relative risk factors associated with suicidal acts in bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD). (a) Relative risk of 31 factors highly significantly (P ≤ 0.01) associated with 371 patients with major mood disorders who were suicidal versus 2913 patients with major mood disorders who were non-suicidal. Factors are shown in descending rank order by risk ratio. (b) Comparisons of strength of association of these risk factors as the ratio of their prevalence or magnitude among patients who were suicidal/non-suicidal, separated by diagnosis (BD, n = 1211, light bars; versus MDD, n = 2073, dark bars), indicating which factors associated more with BD than MDD (upper cluster), which were similarly associated in both (middle cluster) and which were more associated with MDD than BD (lower cluster).

Multivariable logistic regression modelling

Factors preliminarily associated with suicide attempts or suicides among all patients with mood disorders (Table 2) were further tested by stepwise, multivariable logistic regression modelling. In order of strength of independent association with suicidal behaviour, the five significantly and independently associated factors ranked as follows: psychiatric admission to hospital, intake HRSD depression score ≥20, BD diagnosis, onset age ≤25 years, and presence of mixed features in any illness episode (Supplementary Table A1).

ROC analysis

We used factors sustained for association with suicidal acts in multivariable regression modelling for ROC analysis, based on regressing Bayesian sensitivity versus (100 − specificity) or true positive versus false positive rate (Supplementary Fig. A1). The computed AUC was 71.3% (95% CI 68.6–74.0), well above a chance association (50.0%). Optimal differentiation of patients with versus those without suicidal acts was associated with the presence of two factors, optimally yielding sensitivity of 76.0% and specificity of 55.4%, and correct classification of 57.8% of patients as suicidal or not (Table 3).

Table 3 Numbers of factors selectively associated with suicidal acts in 3284 patients with a major mood disorder

Factors tested were: (a) diagnosis of bipolar disorder versus major depressive disorder, (b) intake age ≤40 years, (c) previous admission to hospital, (d) presence of mixed features, and (e) intake Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression total depression score >18.

Discussion

This study provides risks and annualised rates for patients with suicidal acts (attempts or suicides), relative risks of violent and nonviolent suicidal acts, as well as estimated rates of suicidal ideation among 3284 similarly and consistently evaluated patients with major affective disorders at a single study site, with comparisons among the diagnostic types (Table 1). Overall, we found a lifetime risk for suicide ideation of about 68%, for suicide attempts of various severity of 30%, for suicide of 2.8%, and for all acts of 33% during an average exposure time of 14.3 years. The attempts/suicides ratio was similar in patients with BD (11.1) and those with MDD (10.2), and several times lower (greater lethality) than in the general population (at least 30).11 The study also quantified associations of many demographic and clinical factors with suicidal acts (Table 2, Fig. 1a), as well as their relative likelihood among those diagnosed with BD or MDD (Fig. 1b).

As expected, indications of less conventionally successful social functioning were associated with greater risk of suicidal behaviour.Reference Hansson, Joas, Pålsson, Hawton, Runeson and Landén12–Reference Bellivier, Yon, Luquiens, Azorin, Bertsch and Gerard14 Such risk factors included being unmarried or divorced and consequently having fewer children, as well as lower socioeconomic status and more unemployment. These factors are also independently associated with the presence of a mood disorder. Also associated with suicide and attempts were younger illness onset, longer time from onset to intake and older current age, which are all indicative of greater exposure or more years at risk.

Greater suicidal risk was more associated with BD than with MDD, and risk was similar among patients with BD-I and those with BD-II (Table 1). These findings accord with previous observations involving cases of MDD being unselected for illness severity.Reference Tondo, Lepri and Baldessarini6,Reference Bottlender, Jäger, Strauss and Möller15 Co-occurring morbidities associated with suicidal acts included ADHD and substance misuse as well as smoking. However, contrary to expectation,Reference Hawton, Sutton, Haw, Sinclair and Harriss2,Reference Isometsä16,Reference Sánchez-Gistau, Colom, Mane, Romero, Sugranyes and Vieta17 co-occurring anxiety disorders were associated with lower risk of suicidal acts (Table 2B), perhaps by association with a lower degree of impulsivity.

In addition to a BD diagnosis, risk factors associated with suicidal behaviour included indices of greater illness severity: notably, time spent ill or depressed, multiple early recurrences of depression, psychiatric admission to hospital and co-occurring substance misuse (Table 2). Also strongly associated with suicidal behaviour was a history of BD or of suicide among first-degree family members. We also found higher ratings for certain types of affective temperaments, particularly dysthymic and cyclothymic, among patients who were suicidal, as reported previously.Reference Baldessarini, Innamorati, Erbuto, Serafini, Fiorillo and Amore18,Reference Vázquez, Gonda, Lolich, Tondo and Baldessarini19 Particularly of note, the present findings also support a well-known, strong association of suicidal risk with mixed features, including patients diagnosed with either BD or MDD (Table 2).Reference Tondo, Vázquez, Pinna, Vaccotto and Baldessarini9,Reference Saunders and Hawton20–Reference Vázquez, Lolich, Cabrera, Jokic, Kolar and Tondo23 Elements that may connect BD, mixed states and suicidal risk include aggressiveness and other mania-associated characteristics in both juveniles and adults.Reference Diler, Goldstein, Hafeman, Merranko, Liao and Goldstein24,Reference Perugi, Angst, Azorin, Bowden, Mosolov and Reis25

Violent methods of suicide or attempts were identified in 28.4% (95% CI 7.21–49.6) of all suicidal acts (attempts + suicides), more with a diagnosis of BD-I than BD-II or MDD (Table 1) and, as expected,Reference Bradvik26–Reference Forsman, Masterman, Ahlner, Isacsson and Hedstrom28 more with suicides than attempts, and more among men than women. The overall rate of violent acts is somewhat lower than recently reported rates that averaged 45.1% (95% CI 14.8–75.4; 36% for attempts v. 54.6% for suicides, 38.2% among women v. 55.3% in men), probably due to regional and cultural differences.Reference Bradvik26–Reference Forsman, Masterman, Ahlner, Isacsson and Hedstrom28

Another interesting observation is that use of antidepressants alone was much less prevalent among patients who were suicidal than those who were non-suicidal, in contrast to greater use of antipsychotics and mood stabilisers alone or combined with antidepressants (Table 2). This clinical, nonrandomised choice of treatments reflects clinical practice at the study site, in which antidepressants were avoided in favour of antipsychotics or mood stabilisers in patients who are agitated or show mixed features, so as to avoid potentially increasing suicidal risk.

Five factors significantly and independently differentiated patients with versus those without suicidal acts based on multivariable logistic regression modelling: psychiatric admission to hospital, higher depression rating at intake, BD diagnosis, younger at onset and presence of mixed features in one or more illness episodes (Supplementary Table A1). Some of these factors may reflect greater illness severity. ROC analysis found that these risk factors differentiated patients who were suicidal from those who were non-suicidal with an AUC of 71.3%, and that any two of these independently associated factors optimally differentiated those who were suicidal from those who were non-suicidal with maximal sensitivity and specificity (Table 3; Supplementary Fig. A1). Risk factors may be associated with suicidal risk but would be of limited value in predicting suicidal behaviour for particular patients and times. Notably, they must be combined with attention to clinical conditions and behaviours that may be associated with planning for suicide, including verbal statements, organising personal and business affairs or giving away valued possessions.

Limitations

These findings include factors derived from clinical histories and so may include errors of ascertainment. However, these should be similarly likely across the diagnostic groups compared. Observations made in a mood disorder centre might introduce biases, such as bias related to illness severity, although most study patients were referred by primary care clinicians or were self-referred. In addition, the bivariate testing of large numbers of risk factors for association with suicidal status risks finding chance associations. Rather than making Bonferroni-type adjustments of significance, factors with strong preliminary associations with suicidal behaviour were further tested with multivariable regression modelling, as well as by comparing the magnitude of observed bivariate associations overall and between diagnostic groups.

The present findings test and extend extensive previous research on risk factors for suicidal behavior among subjects with a major mood disorder, as reviewed in the Appendix, and add quantitative assessments of the strength and independence of the association of risk factors with suicidal status, comparing them among specific diagnostic groups. Factors with especially strong associations with suicidal acts (P < 0.0001; Table 2) include: BD diagnosis, familial BD or suicide, being unmarried, early illness-onset, being admitted to hospital, substance abuse or smoking, years of illness, and prospective proportion of time ill or depressed, as well as less use of antidepressant treatment alone and greater use of mood-stabilising or antipsychotic medicines. The findings should contribute to improving earlier identification of suicidal risk, supporting preventive interventions, and improving the treatment and prognosis of patients with mood disorders at particularly high suicidal risk.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.167

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Bruce J. Anderson Foundation and by the McLean Private Donors Psychiatric Research Fund (to R.J.B.), as well as by a grant from the Aretaeus Foundation of Rome (to L.T.).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.