Introduction

Unemployment is a constant topic in all modern welfare states and, since the beginning of this century, active labour market reforms are a primary focus of modern welfare states (Barbier and Ludwig-Mayerhofer, Reference Barbier and Ludwig-Mayerhofer2004). Active labour market policies (ALMP) can take different forms, which are implemented during different economic times. During economic recession with high unemployment rates, governments focus their reforms on lowering unemployment rates as fast as possible. Passive benefits are curtailed to save costs and ALMP measures focus on job creation in the public sector, and stricter rules for benefit recipients including sanctions (Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2010), which can be called workfare reforms (Dingeldey, Reference Dingeldey2007). Albeit given less public attention, also in economically prosperous and stable times with low unemployment and even labour shortages in some sectors, policy changes in the unemployment system occur. These more routine policy changes focus on ALMP measures of education and training (Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2010) and are called enabling reforms (Dingeldey, Reference Dingeldey2007).

Both reform sets – workfare and enabling reforms – have to be communicated and explained to the public. Especially for contested reforms, their legitimisation is important for political parties – in particular those in government – in order to sustain or gain support. This legitimisation is based on the communication – or the framing – of the topic of unemployment in specific terms (Pal and Weaver, Reference Pal and Weaver2003). Furthermore, framing can also influence the content of political reforms (Mead, Reference Mead2011). Although the measures and outcomes of different types of ALMP reforms are well-researched (Barbier and Ludwig-Mayerhofer, Reference Barbier and Ludwig-Mayerhofer2004; Dingeldey, Reference Dingeldey2007; Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2010), little is known about the political discourse on ALMP reforms. In particular, little is known on how the framing of workfare and enabling ALMP reforms varies and how political parties frame in these reforms. Existing unemployment framing literature focuses either on passive unemployment benefits (e.g. Esmark and Schoop, Reference Esmark and Schoop2017) or on unemployment in general over a certain time (e.g. Holmqvist, Reference Holmqvist2009). Furthermore, these studies focus only weakly on the individual unemployed, the centre of all ALMP measures. As ALMP were and are still implemented we consider political debates on these reforms as an important subject for the analysis of the framing of unemployment and of individuals who are unemployed. The current study extends the knowledge on framing of unemployment by (1) utilising concepts from the literature on deservingness to understand how the individual, the focal point of all ALMP, may be used in framing political positions (2) comparing framing between workfare and enabling reforms, and (3) studying framing in parliamentary debates in a systematic-quantitative design. Therefore, we utilise the comparison of one workfare with one enabling reform to understand the relation of reform objective with framing of the unemployed in ALMP reforms. Moreover, we investigate how parties differ in their inclination to refer to unemployed persons in such debates and how they are portrayed to legitimise or oppose reform proposals. We thereby answer three interrelated questions. (1) How important are frames of the individual unemployed (compared to framing on the organisational or societal level) in enabling and workfare reforms? (2) To what extent do these individual-related statements mean blaming unemployment on the unemployed or establishing their deservingness? (3) To what extent do parties in parliament differ in their inclination to refer to individual unemployed persons and if to inflict blame or to establish their deservingness?

Empirically, the study is based on one set of workfare and one set of enabling reforms in Germany. In the late 1990s and the early 2000s, Germany was in the midst of a deep recession including a rising unemployment rate, which peaked at 11.2 per cent in 2005 (EU28 8.9 per cent) (OECD, 2018). Against this background, the Social Democratic–Green coalition government enacted a large workfare reform, implementing cuts on unemployment benefits, stricter monitoring of job searches, reintegration agreements, and sanctions for unemployment benefit recipients in case of non-compliance with the new rules. In the late 2010s, Germany’s economy was stable and unemployment low, with an unemployment rate of 4.1 per cent (EU28 8.5 per cent) in 2016 (OECD, 2018). The enabling reforms enacted by the Social Democratic and Christian Democratic coalition government during this time were rather small but focused on the expansion both of social rights (e.g. for people in unstable employment) and of qualification and up-skilling. That both time points are marked by different framing strategies can be assumed by a short look at two public statements, one for each time point. The then chancellor Gerhard Schröder stated in 2001 that ‘people’ – meaning the unemployed – had ‘no right to laziness’ (Helm, Reference Helm2001), whereas then minister of labour Andrea Nahles argued in a press statement in 2016 that the unemployment agency should ‘actively support and accompany the unemployed’ (Nahles, Reference Nahles2016).

In the next section, we provide background information on the reform of unemployment security systems in Germany. In the theory section, we reflect on framing of the unemployed by paying special attention to framing based on abstraction and framing based on blame and deservingness. The subsequent section presents the data and explains the quantitative coding schemes that were used for the analysis. Our results reveal that unemployment framing differs between workfare and enabling ALMPs and sheds light on ideological party differences in the framing of ALMPs. In the conclusion, we reflect on these results and their implications.

Reform context

Until 1983, only the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), the Christian Social Union (CSU; the CDU’s sister party), the Liberal Democratic Party (FDP), and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) were represented in the national parliament. The Green Party (Bündnis ‘90/die Grünen) entered the lower house of parliament in 1983, and the Leftist Party (Die Linke)Footnote 1 entered with the first election in unified Germany in 1990. The parties’ policy positions slightly differ based on the policy field. In the field of economic and social affairs, the Christian parties had a centre right position in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but since the mid-2000s, moved further to the right. Thereby, they adjusted to the position of the Liberal Party who usually take the most right-wing position of the parties in parliament. The Social Democrats inhibit a centre-left position, with the Greens to the left and the Leftist Party on the far left (Pappi and Seher, Reference Pappi and Seher2009).

As many other welfare states, unemployment policy in Germany turned in the early 2000s towards the incorporation of ALMPs (Barbier and Ludwig-Mayerhofer, Reference Barbier and Ludwig-Mayerhofer2004). In, general, ALMPs are supply-side oriented, thus target the unemployed and their employability (Theodore, Reference Theodore2007). They are divided into different types – often two but also more – which differ by their labels but resemble each other in their definitions (Barbier and Ludwig-Mayerhofer, Reference Barbier and Ludwig-Mayerhofer2004; Dingeldey, Reference Dingeldey2007; Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2010). In a first type, ‘emphasis is placed on the pressure (or even compulsion) for the unemployed, particularly welfare recipients, to (re-)enter the labour market, even with low-income jobs’ (Dingeldey, Reference Dingeldey2007: 825). Welfare benefits should relate to strict conditions and sanctions in case of non-compliance. The second type focuses on employability by stressing human capital development often connected to education and training. We adopt the labels employed by Dingeldey (Reference Dingeldey2007) for these types of ALMP; ‘workfare’ for the first type, ‘enabling’ for the second type.

Research on the framing of unemployment in Germany found different frames and different foci. During the Weimar Republic the unemployed were portrayed mainly as people able and willing to work and as being involuntarily in their position due to economic conditions (Flora et al., Reference Flora, Alber and Kohl1977; Zukas, Reference Zukas2001). However, contested views also existed then. Employers framed the unemployed as becoming lazy if they were not monitored, socialists saw them as a threat to the unity of the labour class, and communists constructed them as the capitalist ‘face of inhumanity’ (Zukas, Reference Zukas2001). Especially, the frame of the lazy unemployed, being self-responsible and undeserving has been taken up in the media over the last three decades (Sielschott, Reference Sielschott2010; Bandelow and Hornung, Reference Bandelow and Hornung2019). Positive depictions of the unemployed are rare (Sielschott, Reference Sielschott2010), yet a focus on the macro-economic context in the media discourse has been shown for the Hartz-Reforms (Bandelow and Hornung, Reference Bandelow and Hornung2019).

In the early 2000s, Germany’s economy was in recession, and structural unemployment was high. Under these economic circumstances, the left-wing SPD-Green government coalition, led by the SPD, took up a discourse on controlling the increase of social insurance contributions in order to retain a competitive economy in a globalised world (Seeleib-Kaiser and Fleckenstein, Reference Seeleib-Kaiser and Fleckenstein2007). In this situation, a reform package of four labour market laws was passed in 2002 and 2003, which can be labelled as workfare policies.Footnote 2 This legislation was one of the largest social reform packages in German history and restructured the entire support systems for unemployment. The job placement process and the bureaucratic procedures were guided by new efficiency aims (Ludwig-Mayerhofer et al., Reference Ludwig-Mayerhofer, Behrend, Sondermann, Evers and Heinze2008). Activation in the form of workfare played a crucial role in the reform package by the introduction of target agreements and sanctions in case of non-compliance. Furthermore, the employability was set into focus by determining that each legal job offer has to be accepted by the unemployed irrespective of prior education or job (Legnaro, Reference Legnaro2006). According to Seeleib-Kaiser and Fleckenstein (Reference Seeleib-Kaiser and Fleckenstein2007: 439), the accompanying government communication was based on: ‘promoting greater personal responsibility, [which] constitutes the overall normative frame’. In the literature, these reforms and their effects are discussed as having introduced an individualistic and market-oriented turn in unemployment policy (Knuth, Reference Knuth2006; Legnaro, Reference Legnaro2006; Mohr, Reference Mohr2007; Ludwig-Mayerhofer et al., Reference Ludwig-Mayerhofer, Behrend, Sondermann, Evers and Heinze2008; Hegelich et al., Reference Hegelich, Knollmann and Kuhlmann2011). The legislation spurred vast public criticism as well as inter-party criticism in the SPD, which eventually led to re-elections that resulted in a new government coalition of CDU, who led the government, the sister-party CSU and the SPD (Hegelich et al., Reference Hegelich, Knollmann and Kuhlmann2011). This coalition is called the Grand Coalition due to its large majority, which usually lies around 70 per cent (Deutscher Bundestag, 2019).

The late 2010s marked a time of persistent economic growth and low structural unemployment. The objective of labour market policy was to keep unemployment low and helping those long-term unemployed who could not yet be integrated into the labour market. In 2016, two laws taking up these objectives were sponsored by a Grand Coalition government, again led by the CDU.Footnote 3 Opposed to the Hartz legislation, these reforms focus on ALMP as enabling policies. The first law introduced new measures for qualifications and training for the unemployed as well as an expansion of the eligibility for unemployment insurance benefits for people with several interruptions of their employment history (Bäcker, Reference Bäcker2017a). In the second law, a number of small measures for the long-term unemployed concerning qualifications and training as well as new rights and obligations (especially for people under twenty-five) were passed (Bäcker, Reference Bäcker2017b).

Theory

How social problems are defined, perceived, interpreted, and evaluated is influenced by the way they are framed by political actors and the media (Entman, Reference Entman1993; Benford and Snow, Reference Benford and Snow2000). Put succinctly, ‘framing is concerned with the presentation of issues’ (de Vreese, Reference de Vreese2005: 53). Social science scholarship has demonstrated the significance of framing for power structures and the outcomes of political debates (Snow and Benford, Reference Snow and Benford1988; Steinberg, Reference Steinberg1998; Benford and Snow, Reference Benford and Snow2000; Steensland, Reference Steensland2008). Furthermore, framing by political actors is able to influence public policy (Mead, Reference Mead2011; Rose and Baumgartner, Reference Rose and Baumgartner2013). Parties use framing as a strategy to explain their own reform proposals or to criticise those of others in order to gain public support (Pal and Weaver, Reference Pal and Weaver2003; Druckman, Reference Druckman2004; de Vreese, Reference de Vreese2005). When it comes to welfare state and unemployment reforms, effective framing is an important tool for governments to legitimise reforms and thereby avoid electoral punishment and gain public support (Pal and Weaver, Reference Pal and Weaver2003).

Studies focusing on the framing of unemployment or the unemployed have taken several angles, e.g. medicalisation (Holmqvist, Reference Holmqvist2009), Europeanisation (Lahusen, Reference Lahusen and Heidenreich2006), deservingness (Slothuus, Reference Slothuus2007), and abstraction (Iyengar, Reference Iyengar1990). Responsibility for unemployment or being unemployed is attributed to either the society or the individual (Iyengar, Reference Iyengar1990; van Oorschot and Halman, Reference van Oorschot and Halman2000; Theodore, Reference Theodore2007). This kind of unemployment framing already had a significant influence on the introduction of unemployment insurance schemes in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century (Flora et al., Reference Flora, Alber and Kohl1977). They were introduced as the latest of the big social insurance systemsFootnote 4 in most developed countries (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2005) because the framing of unemployment included largely individualised blame, while the state and interest groups (e.g. employers) were only made liable to a small extent (Flora et al., Reference Flora, Alber and Kohl1977). Only step-by-step, unemployment was constructed and framed as a social risk based on market- rather than individual failure, which sparked the initialisation of societal unemployment schemes (Flora et al., Reference Flora, Alber and Kohl1977: 732). In general, ALMPs focus on the supply-side; accordingly place the individual unemployed at the centre for overcoming unemployment. Hence, if political actors want to legitimise these reforms, they need to connect to the individual measures of the reforms and thus frame unemployment in individual terms. Ascribing unemployment to organisations or to societal changes should be uncommon in both forms of ALMPs – enabling or workfare – because they could not justify the individual level measures.

However, the joint individual nature of ALMPs does not necessarily mean that individual attributions of unemployment have the same meaning in enabling and workfare reforms. Individual unemployment frames such as ‘lack of incentive to work’ or ‘lack of qualifications’ (Esmark and Schoop, Reference Esmark and Schoop2017) tap into prevalent perceptions of deservingness that exist within the population (van Oorschot et al., 2017). Deservingness is defined by the five CARIN criteria (control, attitude, reciprocity, identity, and need). Although all five criteria are important in defining deservingness ‘the weights of criteria differ between individuals and contexts’ (van Oorschot and Roosma, Reference van Oorschot, Roosma, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017: 16). In the European context, widespread negative images on the unemployed revolve around ‘doubt about unemployed people’s willingness to work and about proper use of benefits’ (van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2006: 25). Thus, the ‘willingness to work’ – or in other terms the control over one’s own situation – paired with the ‘proper use of benefits’ – or the need for benefits – are the two most important deservingness criteria for the unemployed. Moreover, the control over neediness has been shown to be decisive for the amount of personal blame ascribed to the individual unemployed (van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2006; Larsen, Reference Larsen2008). Inflicting blame on individuals for their unemployment or establishing their deservingness are both tools to legitimise reforms (van Oorschot and Halman, Reference van Oorschot and Halman2000; Green-Pedersen, Reference Green-Pedersen2002). Hence, legitimations of workfare reforms should stress high control and low need of the unemployed, thus inflicting blame on them, to justify sanctions on benefits. Yet, the framing of the unemployed in enabling reforms should focus on their low control over but high need for education and training, hence establishing their deservingness.

Since framing in the political debate constitutes a strategic action, both party ideology (left–right) and the executive position of a party (government–opposition) can be decisive in unemployment framing (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Slothuus and Togeby2010; Helbling, Reference Helbling2014). Focusing on party ideologies and party affiliations, left-wing parties and their voters are more oriented toward solidarity and view beneficiaries of both social assistance and unemployment benefits as being more deserving than do right-wing parties and voters, who demand more sacrifices by the unemployed (Blomberg et al., Reference Blomberg, Kallio, Kangas, Kroll, Niemelä, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017; Uunk and van Oorschot, Reference Uunk, van Oorschot, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017; Kriesi and Hänggli, Reference Kriesi, Hänggli, Bernhard, Fossati and Hänggli2019). This left-right positioning based on solidarity and sacrifices has only recently been reinforced for unemployment policy debates on non-active labour market components (Kriesi and Hänggli, Reference Kriesi, Hänggli, Bernhard, Fossati and Hänggli2019). Thus, independent of the type of ALMP reform, leftist parties can be expected to individualise less and blame less than rightist parties. However, the implementation of ALMPs do not follow a clear left–right pattern (Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2010) and consequently ‘activation debates are likely to be more open to cross-camp coalitions and justifications’ (Kriesi and Hänggli, Reference Kriesi, Hänggli, Bernhard, Fossati and Hänggli2019: 224). Accordingly, framing could differ more between government and opposition than between left- and right-wing parties. For example, Esmark and Schoop (Reference Esmark and Schoop2017) found evidence that parties that are in favour of retrenching unemployment benefits use undeservingness frames more often than parties that are against retrenchment. Hence, government parties in workfare reforms, which strengthen the conditionality of benefits, might employ a blame frame more often than the opposition.

Study design

Data

Our analysis is based on a comparison of parliamentary debates on ALMP reforms in Germany from 2002 and 2003 (hereafter referring to only by the year 2003) and from 2016 (see section: Reform Context). The first set of reforms are an example of workfare policies during a time of macroeconomic hardship; the second set of enabling policies during macroeconomic stability.

All debates of the first parliamentary chamber on each law were included.Footnote 5 The coded material includes 108 speeches held in parliament, and given to the protocol, as well as nine written declarations by members of the parliament. These declarations were only used in the parliamentary discussion of the first reform set by members of parliament (or groups of members) to explain their voting decision and their concerns about the law. These declarations are not read in parliament but printed in the official transcripts of the debates. We included these declarations, which are usually about one to three paragraphs long (or five to ten sentences), because they are part of the parliamentary process and communication.

Parliamentary debates on reform proposals are part of the legislative process in Germany. Although decisions on the bill are usually discussed and decided beforehand by the government and parliamentary committees, debates explain and justify these decisions or give reasons for the opposition to the bill (Bleses et al., Reference Bleses, Offe and Peter1997). Furthermore, the parliament and the debates serve as an arena for argumentative campaigning for political support (Bleses et al., Reference Bleses, Offe and Peter1997). The time allotted in each debate to the political parties is based on their parliamentary share. About 80 per cent of speeches held in the German parliament are pre-written (Ismayr, Reference Ismayr2000). In Germany, the government and the political parties dominate the unemployment discourse (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Bernhard, Fossati, Hänggli, Bernhard, Fossati and Hänggli2019), which makes parliamentary debates an adequate source to study political framing.

Coding decisions and coding schemes

Based on the framing and deservingness literature discussed earlier, we developed a two-level quantitative coding scheme that we re-evaluated and supplemented during the test coding (Neuendorf, Reference Neuendorf2016). We coded latent frames, which focus on the meaning of text rather than manifest frames, which are based on the physical components of a text (e.g. words, sentences, text structure) (Neuendorf, Reference Neuendorf2016). Similar to Esmark and Schoop (Reference Esmark and Schoop2017), we constructed a codebook for a guided interpretation of the content (see online supplementary material). The coding units were the paragraphs that already existed in the official transcripts of the debates. Excluding hecklers’ statements, the coded speeches and declarations had 2120 paragraphs. Only paragraphs that had a clear focus on (un)employment and the labour market were coded.

For our first level of coding (Table 1) we distinguish between the level of abstraction to which statements refer: societal, organisational, or individual (Flora et al., Reference Flora, Alber and Kohl1977; Iyengar, Reference Iyengar1990; van Oorschot and Halman, Reference van Oorschot and Halman2000; Theodore, Reference Theodore2007). The societal frame refers to aims, problems, reform solutions, and evaluations based on the structure of society and/or on the labour market, including the benefit systems. The organisational frame addresses organised entities, such as trade unions, employer associations, and employers. The individual frame includes issues of unemployment at the level of each unemployed person or each individual with a specific characteristic (e.g. the long-term unemployed, above fifty years old, single parents) as well as individual policy instruments, such as reintegration agreements.

Table 1 Coding scheme: level of abstraction (first level codes)

This first level of the coding scheme was pretested at two 5 per cent random test samples by both authors separately in order to discuss the challenges of the coding and refine the coding instructions. The reliability based on Cohens Kappa values (Cohen, Reference Cohen1960) was 0.61. These values can be evaluated as having ‘moderate’ to ‘substantial’ agreement based on Landis and Koch (Reference Landis and Koch1977), and the coding scheme can thus be used.

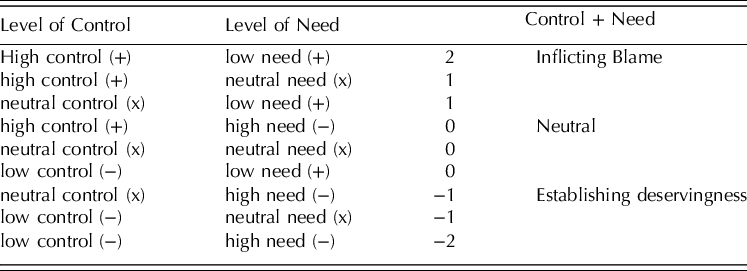

In a second step, only those paragraphs that received a code at the individual level were coded on a second level – the level of blame-deservingness. This level operationalised whether individualisation was used to blame people for their own unemployment or whether it was used to establish deservingness. We used an index based on two dimensions with three categories, with the dimensions based on the need and control deservingness criteria by van Oorschot and Roosma (Reference van Oorschot, Roosma, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017). Negative images of the unemployed are questioning the willingness to work and the reasonable spending of benefits by the unemployed (van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2006), thus their control and need, which influences how much they are blamed for their own situation. The dimensions ‘level of need,’ and ‘level of control’ had both three levels: ‘high,’ ‘neutral,’ and ‘low.’ The level of blame-deservingness was measured by combining the ‘need’ and the ‘control’ codes. It is important to note that the values of the dimensions were reversed. Table 2 shows the coding scheme and the corresponding scale of blame-deservingness, with positive values indicating ‘inflicting blame’ (hereafter also referred to as ‘blame’ or ‘to blame’), values of zero indicating a ‘neutral’ position, and negative values indicating ‘establishing deservingness.’ All paragraphs, which received the individual code on the first coding level, were coded on the dimensions of need and control. In case a paragraph did not contain any arguments on need or control, neutral codes were set. The second level of the coding scheme was pre-tested on a 5.6 per cent test sample. The reliability based on the value of Cohens Kappa (Cohen, Reference Cohen1960) was 0.52.

Table 2 Coding scheme: blame-deservingness (second level codes)

For both analyses, the share of each code on the total number of codes shows how important each frame was (Fengler and Schmidt, Reference Fengler and Schmidt1967; Vowe and Dohle, Reference Vowe, Dohle, Marcinkowski and Pfetsch2009; Esmark and Schoop, Reference Esmark and Schoop2017). For the first level of the coding scheme (the level of abstraction), percentages relate to all coded paragraphs. For the second level of the coding scheme (the level of blame-deservingness), percentages relate to all paragraphs, which have been assigned an individual code on the prior coding level. All coding and the calculation of Cohens Kappa were performed with the software MAXQDA.

Results

Time

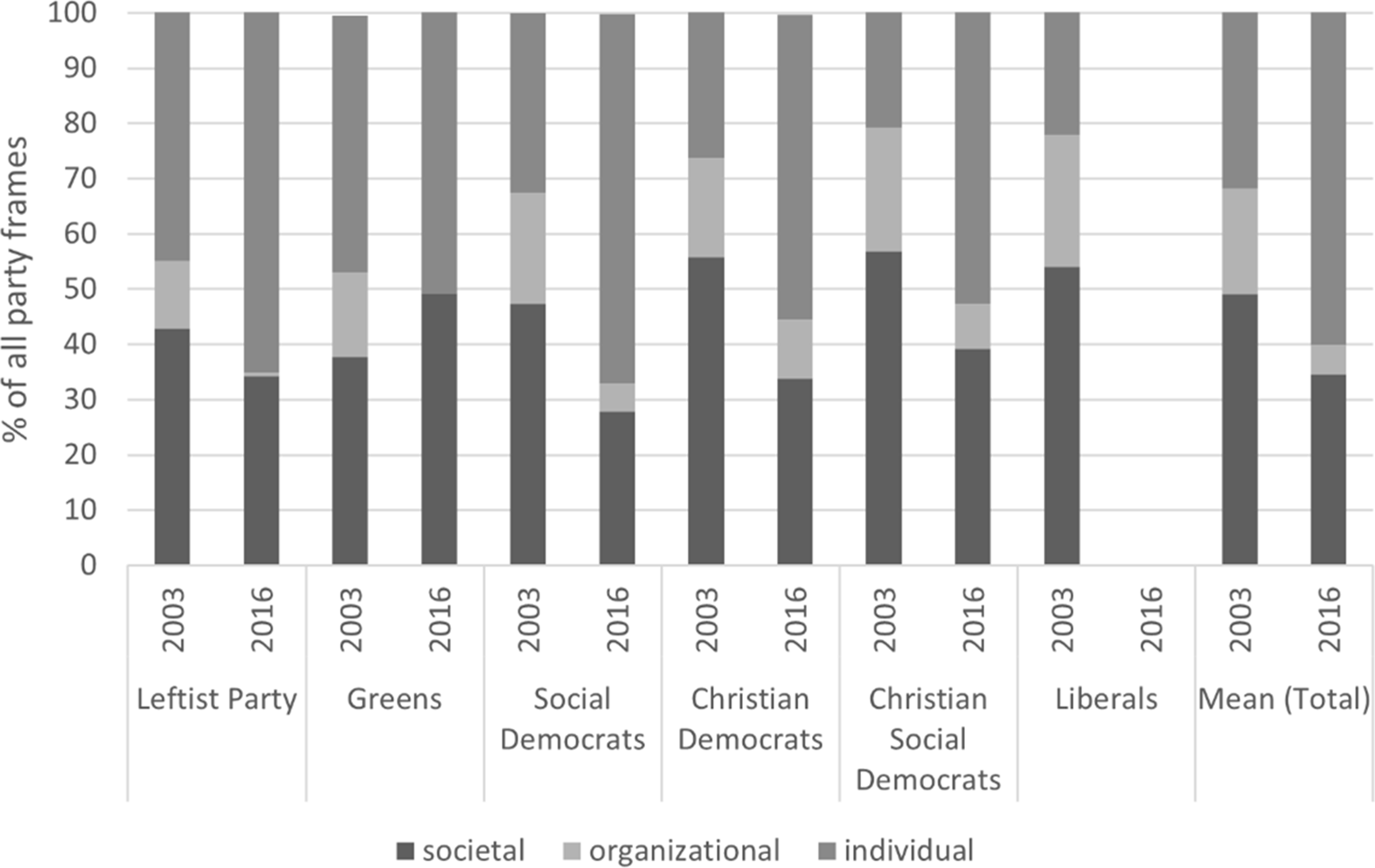

A clear overall trend emerged indicating that unemployment was framed more individualistically in the enabling reforms of 2016 (60 per cent) than in the workfare reforms of 2003 (31.8 per cent) (see Figure 3, mean). In the workfare reforms, unemployment was predominantly framed in societal terms (49.1 per cent compared with 34.6 per cent in 2016), and the focus on the organisational level was higher than in the enabling reforms (19.1 to 5.4 per cent). These findings indicate that the framing of unemployment was more individualised during the enabling than the workfare reforms.

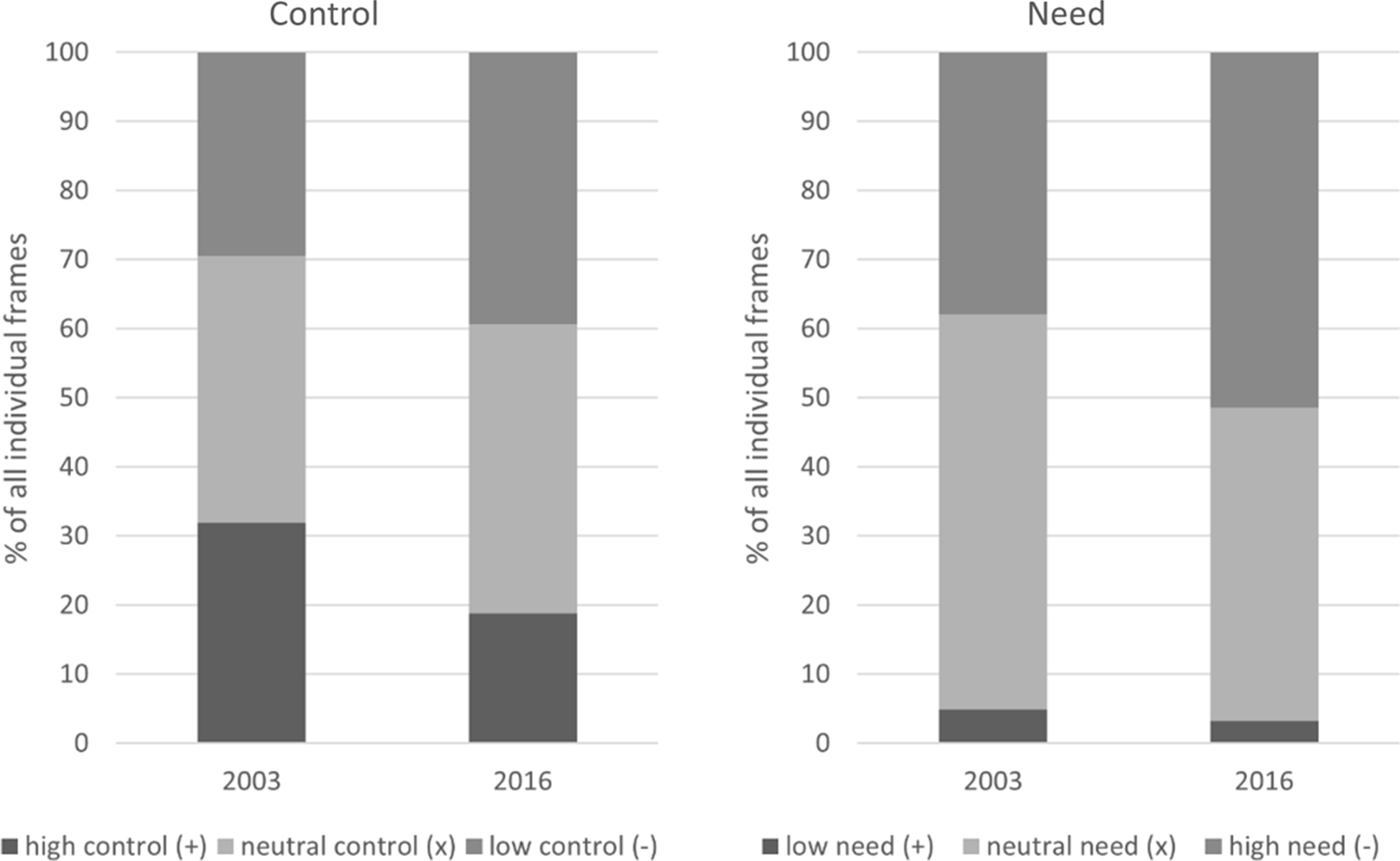

Figure 1. Need and control frames (shares).

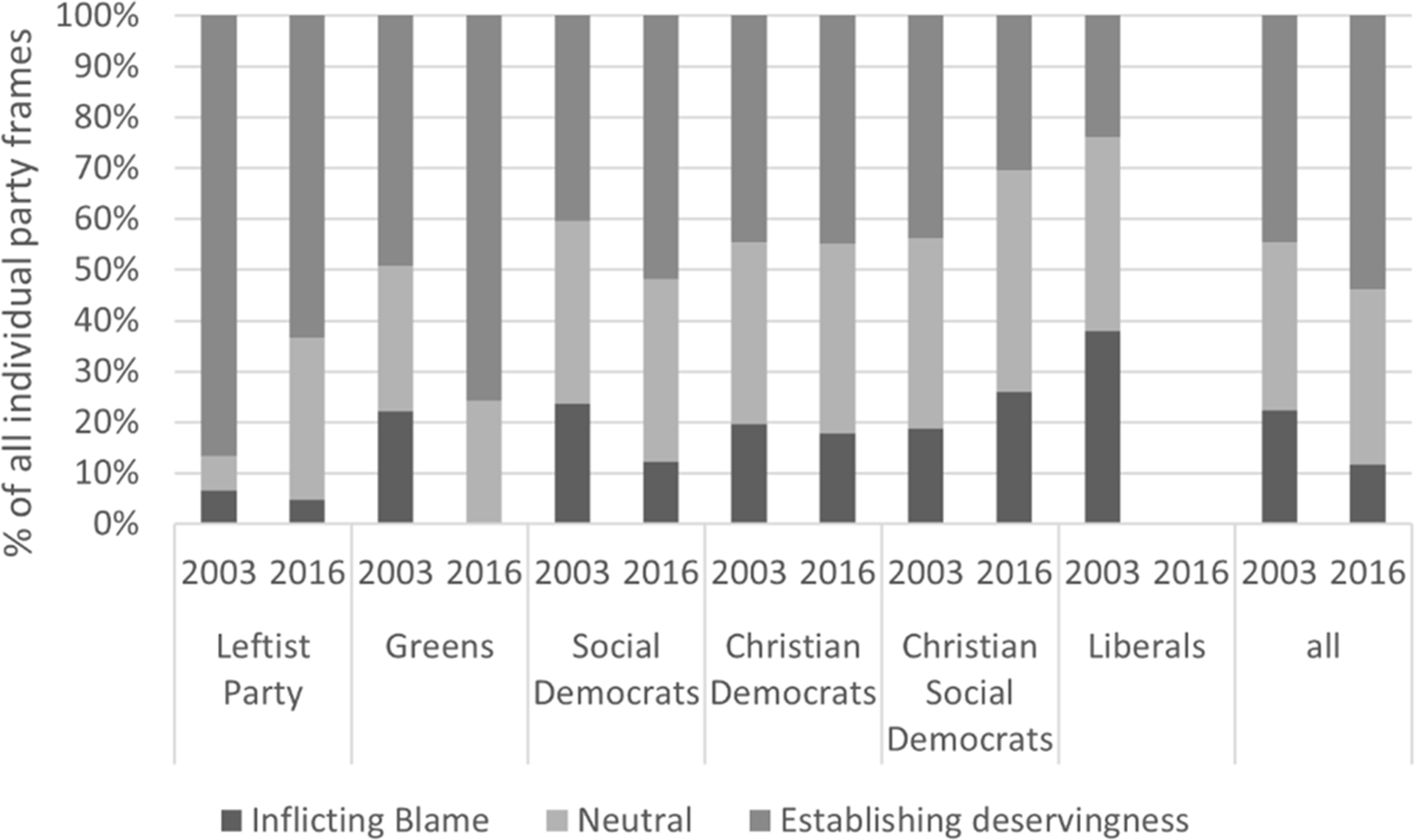

Figure 2. Blame-deservingness framing (shares).

Figure 3. Framing by level of abstraction by party (shares).

In the next step, we were interested in whether the individual frame was used to blame the individuals or rather to establish deservingness. Figure 2 shows that in both enabling and workfare reforms, the ‘establishing deservingness’ frame was more often used than the ‘inflicting blame’ frame. However, blaming was more prevalent during the workfare reforms in 2003 than during the enabling reforms in 2016 (22.5 per cent in 2003 compared with 11.7 per cent in 2016). In the same vein, there was an increase between these two time points in the establishing deservingness frame by 9.1 percentage points (from 44.6 to 53.7 per cent).

The changes were based on both dimensions of the index (Figure 1). ‘High-need’ and ‘low-control’ codes (relevant for the ‘establishing deservingness’ frame) increased, whereas ‘low-need’ and ‘high-control’ codes (relevant for the ‘inflicting blame’ frame) decreased between workfare and enabling reforms. However, ‘low-need’ framing seemed to be nearly non-existent in the German debates on unemployment, with less than 5 per cent of all need codes for both time points. The results thereby indicate: first, that independent of the kind of debated ALMP reform and the economic situation, mainly individuals’ deservingness was established for their own unemployment, or a neutral position was taken; second, despite the fact that inflicting blame upon the unemployed was for both reforms the least common strategy, more blame was inflicted on the unemployed in the workfare than in the enabling reform.

Parties

Furthermore, we were interested in how parties differed in their unemployment framing. We hypothesised that parties’ use of frames could be related both to the party ideology (left–right) as well as to their executive function (government–opposition).

The government was formed by the Social Democrats and the Greens in the workfare reforms of 2003 and by a Grand Coalition of Social Democrats and both Christian parties in the enabling reforms of 2016. The prior findings on the framing of abstraction for both time points were mirrored by the results for the parties (Figure 3). All parties framed unemployment in more individualistic terms in the enabling than in the workfare reforms. Nevertheless, the three parties on the left framed more individualistically than did the rightist parties, independent of the type of ALMP reform. The shares for the individual frame for the Leftist Party, the Social Democrats, and the Green Party were all above the mean (except for the Greens in 2016). Thus, there was a pattern of framing of abstraction due to parties’ ideology; however, no government–opposition divide could be depicted.

Focusing on the amount of blame-deservingness, both the highest and the lowest share of ‘establishing deservingness’ were given in the workfare reforms of 2003 (see Figure 4). The Leftist Party used this frame in 86.7 per cent of paragraphs containing the individual frame, whereas the liberals only used it in 23.8 per cent. All other parties’ shares on this frame ranged between 40 and 50 per cent. The same pattern was visible for the frame of ‘inflicting blame.’ The Leftist Party used this frame in only 6.7 per cent of paragraphs containing the individual frame, whereas the liberals had the highest share, with 38.1 per cent in the workfare reforms of 2003. Interestingly, the shares of the two leftist government parties were higher than those of the two Christian parties: 22.2 per cent for the Greens and 23.7 per cent for the Social Democrats compared with 17.9 and 16 per cent for the CDU and CSU, respectively, in the workfare reforms of 2003. Thus, the most-right and the most-left party in parliament showed a clear ideological divide in the workfare reforms. Both government parties and the two conservative oppositional parties framed less radically. However, the governing parties of the Greens and the Social Democratic Party used the ‘inflicting blame’ frame slightly more than the Christian democratic parties, which hints at an ‘inflicting blame’ strategy of the left government coalition in the workfare reform.

Figure 4. Blame-deservingness framing by party 2003 and 2016 (shares).

This supposition is underpinned by the results of the framing of the enabling debates of 2016 (see Figure 4). At these reforms, there was only a left–right framing pattern but no government–opposition divide. ‘Inflicting blame’ increased, and ‘establishing deservingness’ decreased from left to right. The only exception was the Green Party, which took over the left opposition role from the Leftist Party by inflicting no blame at all and by ‘establishing deservingness’ more than any other party. On the political right, the Christian Social Union was the only party to counter the general trend by an increased use of the ‘inflicting blame’ frame (from 18.8 to 26 per cent) and decreased use of the ‘establishing deservingness’ frame. (43.8 to 30.4 per cent). This move might have occurred because the party took over the role of a right opposition, which had been missing without the liberals in parliament. Overall, a clear left–right divide could be depicted (as for the workfare reforms), yet no government–opposition divide was visible for the enabling reforms.

Overall, we find evidence for more individual framing and more ‘establishing deservingness’ framing by the left than the right for enabling as well as workfare reforms. Furthermore, we could also show that the government ‘inflicted blame’ during workfare reforms to a higher extent than did parts of the opposition.

Discussion

Social scientists have long been interested in how issue characteristics, party affiliation, and the executive position of speakers affect framing in political debates (Steinberg, Reference Steinberg1998; Pal and Weaver, Reference Pal and Weaver2003; Steensland, Reference Steensland2008). In this study, we investigated how the framing of unemployment and the unemployed differed between two different forms of ALMP reforms – workfare and enabling policies – in Germany. Most importantly, we analysed how party affiliation and executive position interact in parties’ use of framing on the level of abstraction and the level of blame-deservingness framing.

The macro-economic situation in 2003 and 2016 differed quite substantially as well as the kind of ALMP reforms. In 2003, Germany struggled with high cyclical and structural unemployment caused by insufficient economic growth and enacted an encompassing unemployment reform, which can be characterised largely as a workfare policy. On the contrary, 2016 was marked by low structural unemployment and economic stability in which more incremental labour market reforms mainly typified as enabling policies were enacted. Based on the literature on unemployment framing (Iyengar, Reference Iyengar1990; Esmark and Schoop, Reference Esmark and Schoop2017) and deservingness (Jensen and Petersen, Reference Jensen and Petersen2017; van Oorschot et al., 2017), we expected similarities and differences in the framing of unemployment. Concerning the level of abstraction, we assumed in workfare as well as in enabling reforms a high level of the individual frame, which outnumbers the societal and organisational frame, because both types of ALMP focus on the supply-side – thus the individual (Theodore, Reference Theodore2007). Regarding the framing of blame-deservingness, we expected high ‘inflicting blame’ framing in workfare reforms and high ‘establishing deservingness’ framing in enabling reforms, because the deservingness of beneficiaries should be questioned in reforms limiting and sanctioning benefits and established in those extending individual qualification rights (Esmark and Schoop, Reference Esmark and Schoop2017). Contrary to our expectation, the study revealed that the individual frame was less often used than the societal frame for the workfare reforms and that the individual frame prevailed in the case of the enabling reforms. However, while blaming the individual was overall an unpopular framing strategy, it was in fact used more often for the workfare reform. Furthermore, the literature on party preferences and the welfare state (Fossati, Reference Fossati, Bernhard, Fossati and Hänggli2019; Helbling, Reference Helbling2014) suggests that party ideology as well as the government–opposition divide might be important for parties’ framing. First, all parties followed the general trend in that the individual frame was more often used in the enabling reforms during economic stability than in the workfare reforms during economic downturn. We expected leftist parties to use less the individual frame than rightist parties. Contrary to our expectation, leftist parties proved to frame unemployment in a more individualistic manner. It is remarkable that all parties used the individual frame more often in the enabling than the workfare reforms, yet our data do not allow for explaining this pattern. One possible reason might relate to the different context of the reforms. The workfare reforms were enacted in a time of recession and high unemployment in which societal causes could not be left out of the framing of unemployment. Nevertheless, also general individualisation trends in society might have influenced this finding (Daly and Scheiwe, Reference Daly and Scheiwe2010; van Gerven and Ossewaarde, Reference van Gerven and Ossewaarde2012).

Party ideology is crucial for the framing of parliamentary debates. Based on research on party ideology (Pappi and Seher, Reference Pappi and Seher2009; Blomberg et al., Reference Blomberg, Kallio, Kangas, Kroll, Niemelä, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017; Uunk and van Oorschot, Reference Uunk, van Oorschot, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017), on the one hand, we expected that – all else being equal – leftist parties would inflict blame less than rightist parties. On the other hand, we assumed that the government would use the blame frame more than the opposition during the workfare reform (Kriesi and Hänggli, Reference Kriesi, Hänggli, Bernhard, Fossati and Hänggli2019). Contrary to our expectation, leftist parties framed unemployment in a more individualistic manner, albeit inflicting less blame. This seems to be the case independent of the content and time point of the reform. Leftist parties thus seem to use the individual frame to demonstrate individual hardship and uncontrollable circumstances to justify the extension of social rights for the unemployed. However, during the workfare reform, the left-wing government blamed more and established less deservingness than expected based on their ideological positioning.

Framing of different ALMPs with a focus on the individual and his deservingness has up to now rarely been examined although research has shown that framing is able to influence public policy and to foster public support for political parties (Pal and Weaver, Reference Pal and Weaver2003; Druckman, Reference Druckman2004; Mead, Reference Mead2011; Rose and Baumgartner, Reference Rose and Baumgartner2013). Our study extends research on the framing of unemployment (e.g. Slothuus, Reference Slothuus2007; Esmark and Schoop, Reference Esmark and Schoop2017) by taking up the deservingness approach and focusing on the individual, the focal point of every ALMP. Our study establishes that the framing of unemployment and the unemployed indeed differs between enabling and workfare ALMPs. Although the individual is the focal point of both types of reforms individual framing is more prevalent in enabling ALMP. Furthermore, framing in enabling reforms focuses more on establishing the deservingness of individuals. Moreover, in contrast to recent research (Fossati, Reference Fossati, Bernhard, Fossati and Hänggli2019; Kriesi and Hänggli, Reference Kriesi, Hänggli, Bernhard, Fossati and Hänggli2019), our study finds that left–right positioning is evident in ALMP reforms and adds that government–opposition specific framing determinates framing in workfare reforms.

Our study has important limitations. First, we cannot rule out the possibility that factors other than changes in the economic situation and the resulting character of the reform influenced the differences in unemployment framing in the German parliament. For example, changes in the general unemployment discourse (Knuth, Reference Knuth2006; Seeleib-Kaiser and Fleckenstein, Reference Seeleib-Kaiser and Fleckenstein2007) or the welfare state discourse (Daly and Scheiwe, Reference Daly and Scheiwe2010; van Gerven and Ossewaarde, Reference van Gerven and Ossewaarde2012) might be the reason for the shifts in time. Additionally, framing might also be influenced by the different party composition of the parliament (Lindbom, Reference Lindbom, Kumlin and Stadelmann-Steffen2014), e.g. the higher share of Leftist-Party parliamentarians in 2016, or the non-representation of the Liberal Party in the parliament of 2016, which yet formed a rightist opposition in 2003. Moreover, welfare state institutions influence the scope for blaming strategies (Larsen, Reference Larsen2008), which might have led to an indirect strategy to just focus on the individual instead of a focus of blaming in the German case. The current study focuses on Germany, a conservative welfare state, and in principle only allows for conclusions relating to this specific case. However, the study reveals differences in the framing of unemployment and unemployed individuals in workfare and enabling policies. As these types of policies have been implemented in the past about thirty years in all mature welfare states, one can assume that differences in framing have occurred in other countries as well. Nevertheless, more studies are needed to investigate and confirm if the framing patterns we find are similar in other conservative welfare states such as Austria but also if these patterns also exist in a social-democratic welfare state such as Denmark or in a liberal welfare state such as the United Kingdom. Furthermore, extending the time frame to include more upswings and downswings of the economy and the labour market and different workfare and enabling policies might reveal more fine-grained results and eliminate other explanatory factors.

Conclusion

Studying the framing of unemployment reform is important because it enables us to better understand discursive political action in a controversial field with potential impact on legislative outcomes and public attitudes toward unemployed individuals. Our study extends the research on welfare state framing by comparing unemployment framing in parliamentary debates with two different ALMP reforms. Based on this comparison, we were able to affirm that (leftist) governments indeed blame individuals more for their own unemployment during workfare reforms. Furthermore, we provided first evidence that in enabling reforms individual framing of unemployment is higher than in workfare reforms. This individualisation was coupled with a decrease in blame framing on the unemployed across the political spectrum. On the one hand, blaming the individual was in fact used more to explain workfare than enabling policies; on the other hand, individual framing was higher in enabling than in workfare reforms. Consequently, individual framing in ALMP differs according to the kind of policy. It will be interesting to see if rising unemployment and subsequent ALMP reforms following the COVID-19 pandemic will show similar patterns of individualisation and blame, because labour market downturn can clearly be attributed to non-individual causes.

List of parliamentary debates

Deutscher Bundestag (07.11.2002) Stenografischer Bericht - 8, Sitzung, Plenarprotokoll 15/8, Berlin.

Deutscher Bundestag (15.11.2002) Stenografischer Bericht – 11, Sitzung, Plenarprotokoll 15/11, Berlin.

Deutscher Bundestag (19.12.2002) Stenografischer Bericht - 16, Sitzung, Plenarprotokoll 15/16, Berlin.

Deutscher Bundestag (20.12.2002) Stenografischer Bericht - 17, Sitzung, Plenarprotokoll 15/17, Berlin.

Deutscher Bundestag (11.09.2003) Stenografischer Bericht - 60, Sitzung, Plenarprotokoll 15/60, Berlin.

Deutscher Bundestag (12.10.2003) Stenografischer Bericht - 67, Sitzung, Plenarprotokoll 15/67 (neu), Berlin.

Deutscher Bundestag (19.12.2003) Stenografischer Bericht - 84, Sitzung, Plenarprotokoll 15/84, Berlin.

Deutscher Bundestag (14.04.2016) Stenografischer Bericht - 164, Sitzung, Plenarprotokoll 18/164, Berlin.

Deutscher Bundestag (15.04.2016) Stenografischer Bericht - 165, Sitzung, Plenarprotokoll 18/165, Berlin.

Deutscher Bundestag (02.06.2016) Stenografischer Bericht – 173, Sitzung, Plenarprotokoll 18/173, Berlin.

Deutscher Bundestag (23.06.2016) Stenografischer Bericht - 179. Sitzung, Plenarprotokoll 18/179, Berlin.

Acknowledgment

The authors received funding for this article from the German Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (AZ: Ia4-12131-1115).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746421000890.