Introduction

Palliative care (PC) aims to improve the quality of life for people with serious illnesses, defined as conditions that carry a high mortality risk, negatively impact the quality of life and daily function, and are burdensome in symptoms, treatments, or caregiver stress (Rabow et al. Reference Rabow, Pantilat, Shah, Papadakis, McPhee, Rabow and McQuaid2023; Yeh and Bernacki Reference Yeh, Bernacki, McKean, Ross, Dressler and Scheurer2017). It involves addressing and managing physical, emotional, and existential or spiritual distress, supporting patients’ families and loved ones, and aligning realistic treatment options with patients’ and families’ goals of care (Gomella and Haist Reference Gomella and Haist2022). The approach integrates care for physical symptoms with psychosocial and spiritual care, considering a patient’s and family’s needs, preferences, values, beliefs, and culture (Gomella and Haist Reference Gomella and Haist2022; Rabow et al. Reference Rabow, Pantilat, Shah, Papadakis, McPhee, Rabow and McQuaid2023; Yeh and Bernacki Reference Yeh, Bernacki, McKean, Ross, Dressler and Scheurer2017). PC can be provided alongside curative treatment at any point in the disease trajectory and may become the sole focus of care near the end of life (Rabow et al. Reference Rabow, Pantilat, Shah, Papadakis, McPhee, Rabow and McQuaid2023; Yeh and Bernacki Reference Yeh, Bernacki, McKean, Ross, Dressler and Scheurer2017).

Approximately, 57 million people worldwide require PC annually (World Health Organization 2020), and around 80% of these were living in low- and middle-income countries (World Health Organization 2020). However, only 14% of patients requiring PC worldwide receive it (World Health Organization 2020). For example, roughly 70% of adults who died between 2012 and 2016 due to chronic diseases in Colombia potentially required PC (Calvache et al. Reference Calvache, Gil and de Vries2020). However, PC services are concentrated in the country’s main cities, and there are several obstacles to the prompt and timely identification of the need for PC by health professionals (Calvache et al. Reference Calvache, Gil and de Vries2020).

Decisions regarding referral to PC represent challenges for health professionals, who may see it as a sign of their failure, and for patients and families – who frequently associate PC with abandonment and death. Consequently, access to these services is often delayed (Cuadrado Franco Reference Cuadrado Franco2019; Gempeler et al. Reference Gempeler, Almonacid and Cuadrado2021; Kaasa et al. Reference Kaasa, Loge and Aapro2018). In addition, about 73% of physicians consider death a negative outcome and even an indicator of therapeutic failure (Cuadrado Franco Reference Cuadrado Franco2019), probably one of the causes of the frequent administration of disproportionate treatments to patients with poor health status or prognosis (Cuadrado Franco Reference Cuadrado Franco2019; Gempeler et al. Reference Gempeler, Almonacid and Cuadrado2021).

A recent integrative systematic review suggests that PC needs should be assessed holistically, including traditional domains such as social or spiritual and emerging ones such as sexual, economic, or health services access (Goni-Fuste et al. Reference Goni-Fuste, Crespo and Monforte-Royo2021). According to this review, only some assessment tools cover all these domains (Goni-Fuste et al. Reference Goni-Fuste, Crespo and Monforte-Royo2021). However, several systematic reviews of instruments that measure unmet needs or PC needs have shown that the Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC) has essential strengths in its development and content-related validity evidence covering the mentioned domains (Afseth et al. Reference Afseth, Neubeck and Karatzias2019; Ahmedzai and Walsh Reference Ahmedzai and Walsh2000; de Heus et al. Reference de Heus, van der Zwan and Husson2021; Hart et al. Reference Hart, Crawford-Williams and Crichton2022; Richardson et al. Reference Richardson, Medina and Brown2007; Waller et al. Reference Waller, Hobden and Fakes2022).

The Academic Unit of Supportive Care at the University of Sheffield worked for over 5 years to develop SPARC (Ahmedzai et al. Reference Ahmedzai, Payne and Bestall2005). SPARC consists of 45 self-rated questions in 8 subscales covering physical and psychological symptoms, communication, and social and personal issues. It is designed to facilitate health-care providers in identifying patients in need of specialized supportive and PC services (Ahmedzai et al. Reference Ahmedzai, Payne and Bestall2005). SPARC has been used in numerous research projects to assess the PC needs of patients with various medical conditions (Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, Hughes and Winslow2015; Gardiner et al. Reference Gardiner, Gott and Ingleton2013; Maguire et al. Reference Maguire, Connaghan and Arber2020; Rutchik et al. Reference Rutchik, Resnick and Bliss2010; Stewart et al. Reference Stewart, McKeever and Braybrooke2019; Wilcock et al. Reference Wilcock, Hussain and Maddocks2019) and has been validated in English, Polish, Korean, and Taiwan Chinese (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Ahmed and Winslow2015; Kwon et al. Reference Kwon, Baek and Kim2021; Leppert et al. Reference Leppert, Majkowicz and Ahmedzai2012; Tsai et al. Reference Tsai, Chou and Loh2023).

Currently, there are no instruments available in Spanish to assess PC needs in diverse patient populations and suited for use in the Colombian population. For an instrument to be applicable and valuable, it is essential to carry out a linguistic validation that goes beyond simple translation processes, seeking not only conceptual, semantic, or technical equivalence but a genuine social and cultural equivalence that adapts to the sociological, demographic, and historical particularities of the target culture and population (Siyu Reference Siyu2016).

A cultural match is crucial when adapting versions of content, as even slight variations in meaning can alter how the item is perceived and answered (Zou Reference Zou, Weiguo, Guiran and Huiyu2016). While the intent of specific items may be clear, linguistic nuances can result in conceptual disparities that are not easily detected (Menon and Venkateswaran Reference Menon and Venkateswaran2017). This is particularly true when significant cultural differences or variations in qualifying symptoms exist between the groups involved (Menon and Venkateswaran Reference Menon and Venkateswaran2017). Therefore, we translated and performed a cross-cultural validation of the SPARC for Colombia (entitled SPARC-Sp) (Polit and Yang Reference Polit and Yang2016), focusing here on the cultural equivalence of the instrument using qualitative data collection and analysis methods. The results of the psychometric characteristics will be presented separately.

Methods

The SPARC was chosen as the instrument to be translated, culturally adapted, and validated in this study. This decision was made after a panel of health-care professionals and patients from both the United Kingdom and multiple cities in Colombia informally concluded (in the framework of the project “Living with and beyond cancer” (Reid et al. Reference Reid, Vries and Ahmedzai2021)) that the SPARC construct of the measurement of holistic needs was suitable to warrant moving on to a translation (conceptual equivalence). Similarly, these experts expected that the methods of applying SPARC and measuring these needs (technical equivalence) would be congruent with the Colombian cultural beliefs, values, and experiences, based both on intimate knowledge of the Colombian context and other international experiences with SPARC (Kwon et al. Reference Kwon, Baek and Kim2021; Leppert et al. Reference Leppert, Majkowicz and Ahmedzai2012; Polit and Yang Reference Polit and Yang2016). Figure 1 shows the stages of the methods used in this study, largely following cross-cultural validity study phases as described by Polit and Yang (Reference Polit and Yang2016).

Figure 1. Stages of methods used in the study.

Translation, reconciliation, and back-translation

Three independent researchers fluent in English and with theoretical or practical knowledge of PC (JAC, SM, and EdV) and one professional language translator living in Colombia were given the task of performing an initial English-to-Spanish-centered translation (Polit and Yang Reference Polit and Yang2016) of the 45 SPARC questions, the answer options, and the questionnaire’s instructions – aiming for semantic equivalence rather than a literal translation.

A panel of native Spanish speakers (JAC and two anesthesiology residents – CC and KR) was assembled to review and reconcile the four translations into a single version. A second panel of Spanish-speaking experts (JAC, SM, and EdV) verified this first version (SPARC-Sp) before undergoing the back-translation process. Two bilingual native translators (English and Spanish – external to the research team and unaware of the original SPARC questions) and a professional translator back-translated SPARC-Sp into English. This back-translated version was checked for consistency with the original English version of SPARC under the supervision of Dr. Ahmedzai, the initial developer of SPARC. Discrepancies related to linguistic, cultural, and social differences and variations in health systems were discussed and finally reconciled by the international expert panel (JAC, SM, EdV, and SHA).

Comprehensibility and feasibility assessment

To make a more extensive assessment of the comprehensibility of SPARC-Sp and the feasibility of its use, a focus group with the implementation facilitators (research assistants who applied SPARC-Sp in the hospitals) was conducted during the application of the instrument for its psychometric validation.

To conduct the focus group, three researchers (EdV, JAC, and CVM) designed a question script using an iterative approach to explore linguistic and semantic aspects of the questions and to ask the participants to formulate alternative modifications to facilitate understanding and communication with the patients. Additionally, we explored the perceived capabilities and potential use of SPARC-Sp in a clinical setting.

Acceptability testing

To evaluate the general acceptability of SPARC-Sp beyond the specific context in Popayán where the instrument was being validated, we undertook a survey of patients, caregivers, and health personnel through social networks, expert organizations, PC organizations, and health workers with experience in PC management in Colombia.

The survey included 15 open-ended, 9 dichotomous, and 10 Likert-type questions. Three researchers constructed the survey questions from an iterative approach (SM, EdV, and CVM). The participants were asked to rate the relevance of domains and items of SPARC-Sp and suggest additional items if they felt this was needed.

Participants answered the online survey (SurveyMonkey R.) from November to March 2023.

The focus group information and the answers to the survey’s open-ended questions were transcribed verbatim. CVM carried out thematic analysis under the supervision of EdV, SM, and JAC. We coded the information and constructed categories. Authors could suggest or modify new categories. To improve rigor, the proposed categories were presented back to the focus group and survey participants to assess if their perspectives were adequately represented and considered.

Ethical approval

The protocol of this project was evaluated and approved by the Ethics Committee at the Hospital Universitario San Jose, Popayan, Colombia (8.2.9-92/031). All included patients and participants confirmed their voluntary and informed participation by signing informed consent forms.

Results

Translation and back-translation

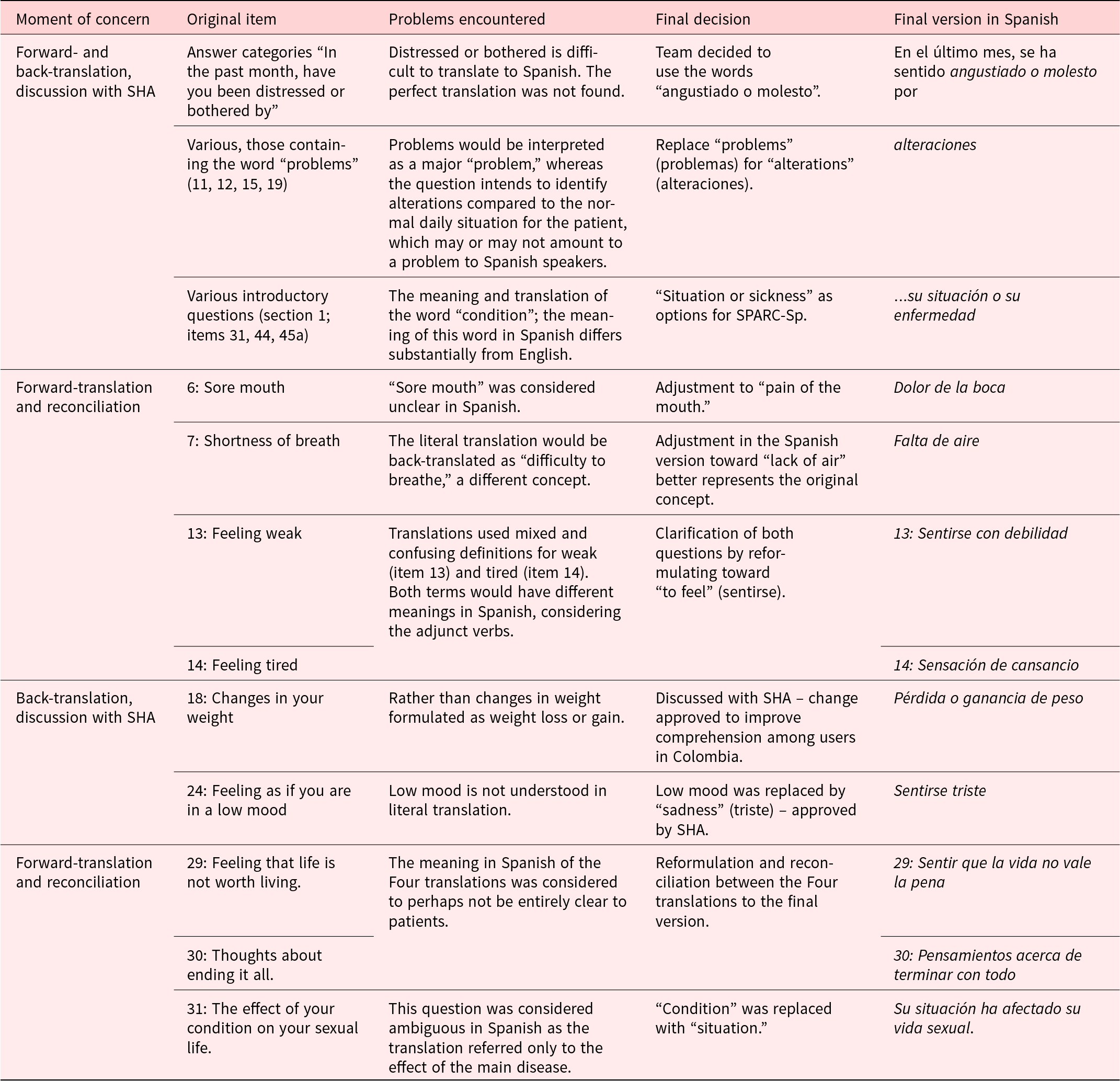

During the initial harmonization of the four initial English-to-Spanish translations, differences and difficulties were found in some items. Moreover, in the back-translation (English-to-Spanish), there were some issues detected by the original author of SPARC (SHA) and the panel clarified these. These issues of the forward- and back-translations and the final version of the translated words or sentences are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Difficulties encountered in the process of forward- and back-translation or conciliation between versions of the translations and the final version in Spanish

SHA = Sam H. Ahmedzai, developer of the original SPARC instrument.

Comprehensibility and feasibility assessment

The initial SPARC-Sp testing was conducted in a focus group held at the Hospital San Jose de Popayan. This university-affiliated hospital serves diverse populations, including indigenous communities. A significant proportion of the latter patients are illiterate or have deficient educational levels (59% with incomplete primary school). There were five research assistants for applying SPARC-Sp. These facilitators included medical students, anesthesiology residents, general physicians, nutritionists, and nurses. These facilitators participated in focus groups to evaluate both the comprehensibility and feasibility of SPARC-Sp as experienced in the field test.

The facilitators expressed reservations about using the SPARC-Sp in patients with low literacy levels. They considered that these patients might need additional help in understanding the meaning of some of the questions and, therefore, could give answers that were not informative or accurate.

In our environment [Colombia], it’s difficult to understand certain terminology. It’s difficult to understand for certain groups of patients (…) and lends itself to difficulties in understanding the question (according to SPARC-Sp). (Doctor, Anesthesiology resident, male)

According to the facilitators, the SPARC-Sp evaluation options “not at all, a little bit, quite a bit, very much” could confuse the patients, and the facilitators had difficulties explaining the differences between these categories.

What is a little, what is much, or what is very much? In other words, the instrument should have operationalizations of the answer option to each item so that one can tell the patient. (Medical student, male)

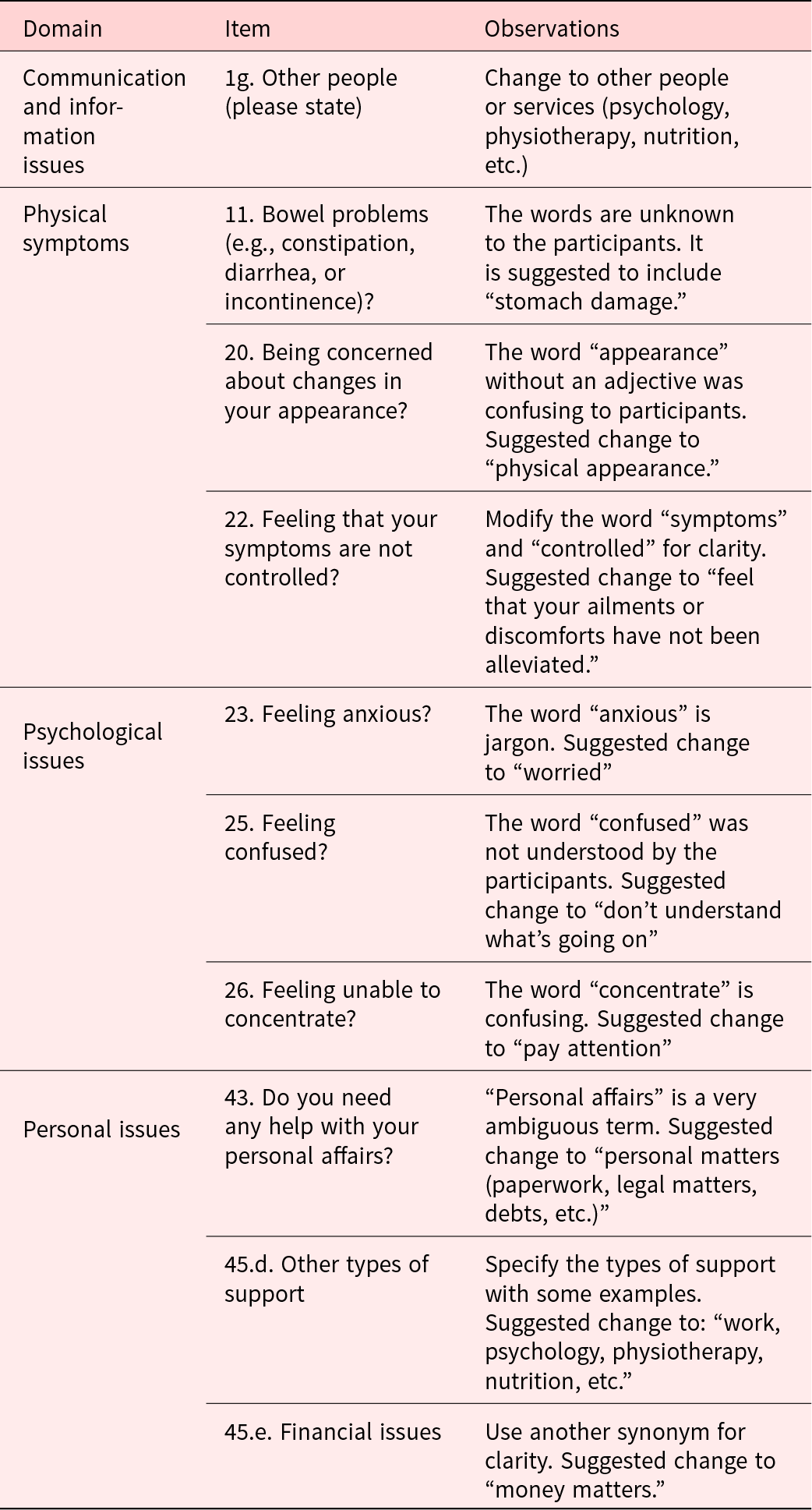

Table 2 presents the items identified in each domain that could were considered candidates for modifications to improve clarity and comprehensiveness based on the data obtained in the focus group with implementation facilitators.

Table 2. Suggested adjustments or modifications to improve the comprehension of the SPARC-Sp items

All implementation facilitators described SPARC-Sp as helpful for identifying and communicating holistic PC needs between the patients, their families, and health-care professionals. One of them, a medical student, expressed that he realized, because of his experiences applying SPARC-Sp, that neither doctors nor nurses usually approach the patients to interact with them:

Most doctors, in the hospital rounds, don’t have the time to approach and talk, because normally for the questions here [communication and information domain] always [the patients] tell me no, they don’t talk to the doctor, or the nurse. (Medical student, male)

The facilitators recognized multiple advantages in applying SPARC-Sp to recognizing dimensions other than the physical domain:

They [the patients] are never asked if they need emotional support (…). SPARC-Sp allows them to rethink many things about themselves, and they say: - “Yes, I mean, the medication is helping, but I need more. I mean, the pills are not enough. (Medical student, male)

It touches the patient’s sensitive topics (…) the patient cries and has the perception that he is really alone, that he really wants to end it all and that he needs something more holistic for him. (Medical student, male)

From their observations and comments by the patients answering SPARC-Sp, the facilitators noted that some important holistic needs related to the Colombian geographical and logistic characteristics and the health-care system were not covered by SPARC-Sp:

We also see the influence of geography (large rural area, lack of road infrastructure), which has a direct influence on adherence to treatment, and the possibilities of whether or not a patient can be followed up. (Head of Nursing, female)

The health system has abandoned them, and care is not provided as it should be (…). The times available for one consultation do not allow us. The health is running away all the time; it doesn’t justify the consequences they have for them (patients). So many times, (…) I read a medical history and think this lady must be in a terrible state. I read it, I go, I look, and the patient goes: − ‘No, I’m fine.’ … She’s not fine, she’s about to die! In other words, she’s not well. She is in a bad condition, but I’m very struck by the perception [of being «fine»]. (Medical student, male)

The facilitators considered SPARC-Sp to be long and difficult to implement in routine clinical practice:

Definitely it should be a bit more concise, eh, not so extensive, more punctual and specific with the questions. (Head of Nursing, female)

For facilitators, the length and duration of SPARC-Sp administration, especially when the patient requires assistance to complete it, made its foreseen use in control visits problematic, especially when used in a face-to-face application in this particular social and demographic setting.

Some facilitators considered that implementing SPARC-Sp on mobile devices could facilitate its routine use in clinical practice.

It should be self-applicable by digitized means, but realistically, I think it is difficult. (Head of nursing, female)

Since there are so many patients where you [the clinician] are the one who ends up writing [marking SPARC responses] because the patient is not in a capacity … You basically sit there with the instrument, filling it out. (General physician, male)

This cited physician mentioned that he thinks that using an electronic device with the questions available as both written and audio-recorded options would make self-administration feasible.

The process of assisting patients completing SPARC-Sp was emotionally heavy for the facilitators:

Sometimes, after applying this tool with patients, I am impacted by the emotional burden that the patient has. And not only the patient but also their family. (Doctor, Anesthesiology resident, female)

Acceptance testing

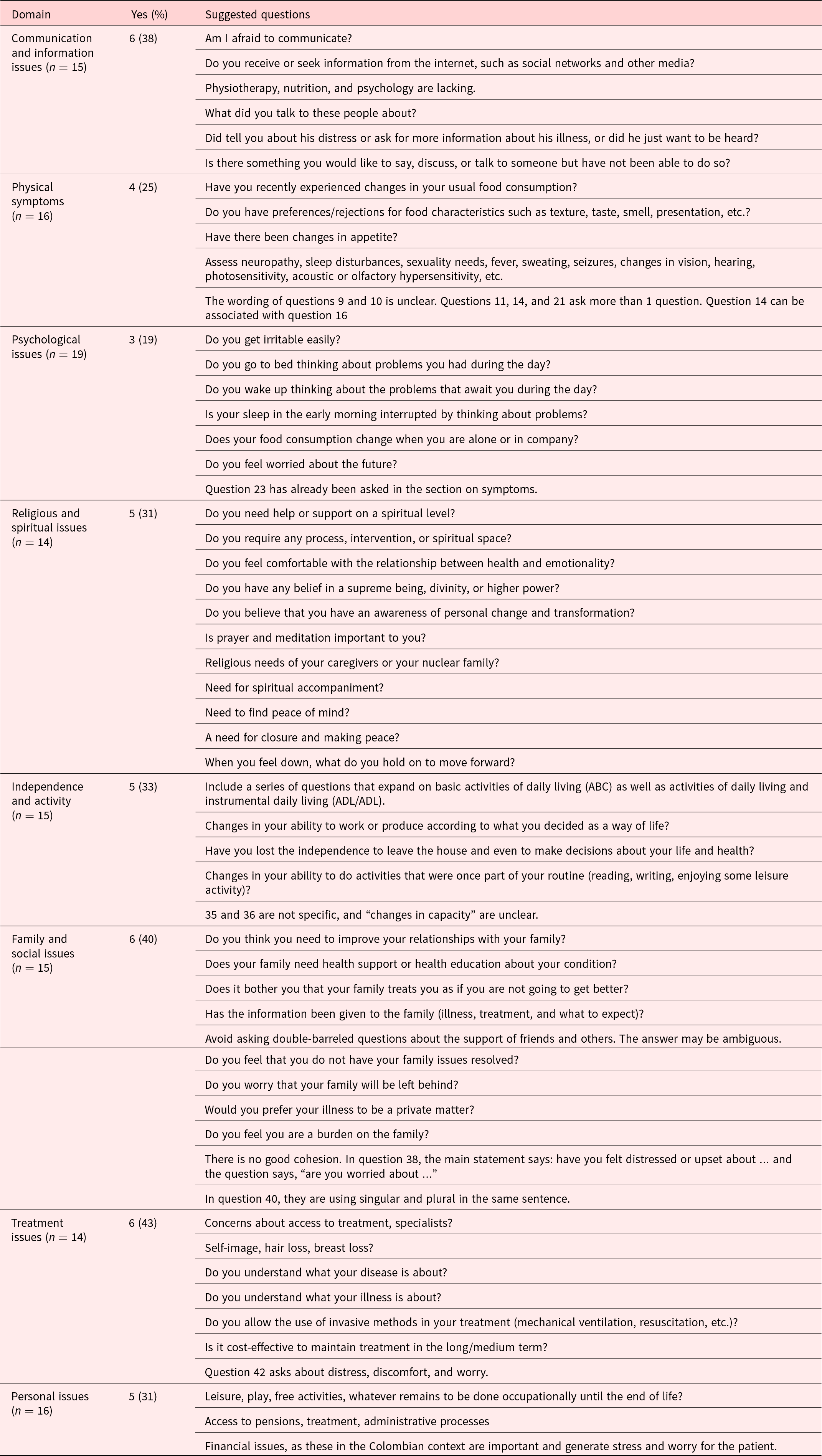

A total of 29 participants responded to the SPARC-Sp acceptability survey (Methods, 2.3), of which 48% (n = 13) were nurses, 22% (n = 6) medical doctors, 19% (n = 5) were other health professionals (n = 5), 15% (n = 4) patients, 7% (n = 2) careers, 4% (n = 1) user representatives, and 4% (n = 1) decision-makers. We identified several suggested items for the 8 domains of SPARC-Sp (Table 3).

Table 3. Proposals for additional questions to be included in the SPARC-Sp domains

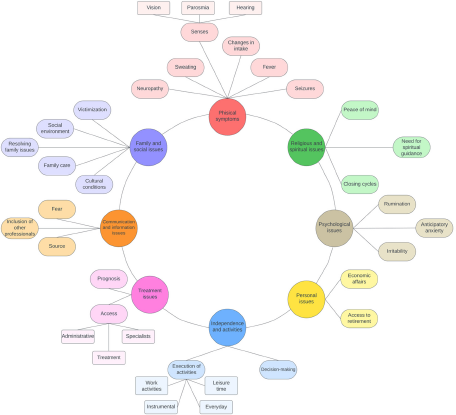

During the focus groups, the facilitators offered suggestions on attributes that could be included in the dimensions of the SPARC-Sp. Figure 2 shows a synthesis of the domains and aspects that participants in both the focus group and the survey suggested being added to the SPARC-Sp.

Figure 2. Synthesis of domains and suggested aspects to be included in SPARC-Sp.

Discussion

The results of the translation and the subsequent linguistic and cross-cultural validation processes showed that achieving semantic equivalence between two instruments is challenging; many concepts in medicine or “well-being” are conveyed to the reader slightly differently when using direct translation. Eventually, after the careful conciliation of the initial English-to-Spanish translation, the back-translation of the SPARC-Sp was considered semantically equivalent to the original version by the experts. However, when asking many users (patients, caregivers, and professionals) how they understand and interpret the items, some items still required adjustment to make the entire instrument equivalent and unequivocally understandable. Previous validations of translated versions of SPARC, such as the one conducted in South Korea, also reported subtle changes in the use of particular words, especially in psychological, religious, and spiritual domains (Kwon et al. Reference Kwon, Baek and Kim2021). In this Spanish version, participants had difficulties meaning several words (bowel problems, appearance, symptoms, anxiety, confusion, and concentration). The validations of SPARC in Korea and Poland were limited to oncology patients with advanced disease and good literacy skills (Kwon et al. Reference Kwon, Baek and Kim2021; Leppert et al. Reference Leppert, Majkowicz and Ahmedzai2012). In contrast, this study included a very heterogeneous group of patients with chronic non-communicable diseases and all educational levels attended to the hospitals, including a substantial proportion of persons with reading difficulties.

Even though the initial evaluation of the technical equivalence for SPARC and SPARC-Sp (both being considered to be of a literacy level that would allow for self-administration) – the field test showed that many patients still needed help reading the questionnaire. The main suggested adaptation in developing SPARC-Sp was to make adjustments to make it self-administrable, including for people who have difficulties in reading or writing. In low- and middle-income countries, the levels of illiteracy or difficulties in reading comprehension are still high (Instituto de Estadística de la UNESCO and Equipo del Informe de Seguimiento de la Educación en el Mundo 2019; Smartic 2022). Even though most of the Colombian population has now had at least primary education (The World Bank 2022), in practice, many people have difficulties understanding written text (Smartic 2022), and it is likely that this understanding is more challenging in medical settings. These low levels of (health) literacy skills are common in Colombia and most of Latin America (Arrighi et al. Reference Arrighi, Ruiz de Castilla and Peres2021) and represent a big challenge for self-administered questionnaire-based research. The common solution is to apply instruments only to persons with good reading skills, potentially leaving substantial parts of the population out of the exercise. Neither the original SPARC nor the previous translations and validations of SPARC in South Korea and Poland ran into these problems in their country settings.

The adaptation of SPARC-Sp to be self-administrable, especially for persons who can hardly read or write, implies both formulations of more formal and informal wording in the same item (e.g., “mal de estómago” (having a bad stomach) in addition to the more formal “gastric problems”), to facilitate people of low literacy. Other solutions include offering SPARC-Sp as an audio-recorded option for the questions. To deal with the perceived ambiguity for some Spanish-speaking user in the four response categories, it was suggested to use color-coded response levels from green to red. These potential adaptations in the wording and administration format would need to be further tested and calibrated to determine the psychometric properties for future research.

Regarding the evaluation of content equivalence, all Colombian persons involved in the evaluation considered that an instrument aimed at measuring the holistic needs of patients with chronic diseases needs to include a domain assessing the need for help in navigating the administrative and other barriers in the health-care system (Esteve and Gómez Reference Esteve and Gómez2015; Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Amado and Rueda2019; Vargas et al. Reference Vargas, Mogollón-Pérez and De Paepe2016). Examples of administrative barriers are the numerous procedures and authorizations required to access medications, appointments, procedures, home support, etc. Patients or their caregivers usually spend much time and energy on such paperwork (Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Amado and Rueda2019). Other health-care system-related barriers include poor clinical information transfer and communication difficulties between health-care providers, fragmentation and instability of health networks leading to frequent changes of attending physicians, long waiting times for many treatments, insufficient supply of specialists and supplies, poor infrastructure, lack of PC services in many parts of the country (Calvache et al. Reference Calvache, Gil and de Vries2020; de Vries et al. Reference de Vries, Buitrago and Quitian2018; Reid et al. Reference Reid, Vries and Ahmedzai2021; Sánchez-Cárdenas et al. Reference Sánchez-Cárdenas, León and Rodríguez-Campos2021; Vargas et al. Reference Vargas, Mogollón-Pérez and De Paepe2016), and sometimes high out-of-pocket expenses (sometimes for treatment but also for time off work, transportation, and housing to distant cities where they receive attention) (de Vries et al. Reference de Vries, Buitrago and Quitian2018, Reference de Vries, Vergara-García and Karduss-Preciado2021; Garcia-Subirats et al. Reference Garcia-Subirats, Vargas and Mogollón-Pérez2014).

Whereas a screening instrument like SPARC-Sp cannot cover all these issues, it is important that health-care providers are aware of the specific difficulties. In some circumstances, specific adjustments in drug prescriptions or referrals to other services can help solve some of these problems and establish a timely care plan (Goswami Reference Goswami2021). In Colombia, some hospitals have specific social workers to help solve the administrative barriers. Whereas some of these difficulties are very specific to Colombian settings, others may also exist in other countries, from low- to high-income (Abate et al. Reference Abate, Solomon and Azmera2023; Osman et al. Reference Osman, Shrestha and Temin2018; Sedhom et al. Reference Sedhom, MacNabb and Smith2021).

These two sets of adjustments aimed at serving a low-literacy population and including a domain for health-care system-related problems have so far not been identified in the other translation and validation exercises performed with SPARC, but we suspect they – or variations of them – could probably be relevant to other populations as well. Colombia is not the only country with a high proportion of low literacy population and health-care system issues are present in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. They may lead to adding an extra (optional) domain without altering the structure of the original SPARC and SPARC-Sp domains, which would preserve cross-language and cultural comparisons in the future. Such a move could greatly enhance the ability to implement SPARC-Sp in clinical practice in a Colombian setting. These adjustments are currently being considered as part of a web-based tool; however, it is acknowledged that in itself, it would have the disadvantage of being only available in areas with reasonable internet access, a requirement that in the mountainous and rural country of Colombia cannot be fulfilled everywhere. Therefore, we envisage there will be both a paper-based and electronic version of SPARC-Sp.

An instrument could not include all the aspects suggested by the participants in the focus groups, would be too long to administer, and to provide holistic PC, and the level of detail expressed by these participants would not fit into a screening instrument. However, the information provided is relevant to understanding the expectations of health-care teams regarding PC needs in our population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Javier Orozco, MD, and Isabela Bolaños, medical student, for their support and help during the focus groups. To the patients for agreeing to complete the questionnaire as part of their medical care routines. To each and every participant for their invaluable assistance in modifying and adapting SPARC.

Funding

The project did not receive external funding. Their respective employers covered the authors’ and research assistants’ time.

Competing interests

None of the authors report a conflict of interest.