It is well documented that maternal depression predicts both children’s internalizing symptoms (e.g., social withdrawal, sadness, and somatic problems) and externalizing symptoms (e.g., behavioral problems, impulsivity, aggression, and hyperactivity; Bagner et al., Reference Bagner, Pettit, Lewinsohn, Seeley and Jaccard2013; Baker, Reference Baker2018; Connell & Goodman, Reference Connell and Goodman2002; Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Rouse, Connell, Broth, Hall and Heyward2011; Silk et al., Reference Silk, Shaw, Forbes, Lane and Kovacs2006). Despite a historic emphasis on the effects of maternal depression, research has increasingly recognized the independent and additive effects of paternal depression on children’s psychopathology and development (Connell & Goodman, Reference Connell and Goodman2002; Gutierrez-Galve et al., Reference Gutierrez-Galve, Stein, Hanington, Heron and Ramchandani2015; Ramchandani et al., Reference Ramchandani, Stein, Evans and O’Connor2005). In fact, the presence of both maternal and paternal depression is associated with a doubling risk of emotional and behavioral problems in children (Carro et al., Reference Carro, Grant, Gotlib and Compas1993; Fletcher et al., Reference Fletcher, Feeman, Garfield and Vimpani2011; Ramchandani et al., Reference Ramchandani, Stein, O’Connor, Heron, Murray and Evans2008; van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, van der Ende, Crijnen, Jaddoe, Moll, Mackenbach, Hofman, Hengeveld, Tiemeier and Verhulst2009). Prior literature has consistently shown that both maternal and paternal psychopathology predicts the development of internalizing and externalizing symptoms across childhood (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Cheung, Koss and Davies2014; Elgar et al., Reference Elgar, Mills, McGrath, Waschbusch and Brownridge2007; Weissman et al., Reference Weissman, Wickramaratne, Gameroff, Warner, Pilowsky, Kohad, Verdeli, Skipper and Talati2016). Although maternal depression is believed to have a stronger impact on children’s development (Connell & Goodman, Reference Connell and Goodman2002; Kane & Garber, Reference Kane and Garber2004; Klein et al., Reference Klein, Lewinsohn, Rohde, Seeley and Olino2005; Ramchandani et al., Reference Ramchandani, Stein, Evans and O’Connor2005, Reference Ramchandani, Stein, O’Connor, Heron, Murray and Evans2008; Rohde et al., Reference Rohde, Lewinsohn, Klein and Seeley2005; Wilson & Durbin, Reference Wilson and Durbin2010), a burgeoning literature demonstrates the distinct and additive role of paternal depression for children’s internalizing and externalizing disorders (Carro et al., Reference Carro, Grant, Gotlib and Compas1993; Fletcher et al., Reference Fletcher, Feeman, Garfield and Vimpani2011; Giallo et al., Reference Giallo, Cooklin, Wade, D’Esposito and Nicholson2014; Ramchandani et al., Reference Ramchandani, Stein, Evans and O’Connor2005, Reference Ramchandani, Stein, O’Connor, Heron, Murray and Evans2008). Furthermore, maternal and paternal psychopathology have been shown to uniquely effect children’s socioemotional and behavioral functioning (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Keller and Davies2005; Ramchandani et al., Reference Ramchandani, Stein, Evans and O’Connor2005; Sweeney & MacBeth, Reference Sweeney and MacBeth2016).

While some work has found that maternal depression more strongly predicts internalizing disorders and paternal depression more strongly predicts externalizing disorders (Connell & Goodman, Reference Connell and Goodman2002; Kane & Garber, Reference Kane and Garber2004; Low & Stocker, Reference Low and Stocker2005), others have found that maternal depression predicted later externalizing symptoms more strongly than paternal depression (Tyrell et al., Reference Tyrell, Yates, Reynolds, Fabricius and Braver2019). Increased marital conflict and increased maternal depression have been hypothesized to explain these links between paternal depression and children’s psychopathology (Connell & Goodman, Reference Connell and Goodman2002; Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Keller and Davies2005; Giallo et al., Reference Giallo, Cooklin, Wade, D’Esposito and Nicholson2014; Gutierrez-Galve et al., Reference Gutierrez-Galve, Stein, Hanington, Heron and Ramchandani2015; Ramchandani et al., Reference Ramchandani, Stein, O’Connor, Heron, Murray and Evans2008; Sethna et al., Reference Sethna, Murray, Netsi, Psychogiou and Ramchandani2015; Trautmann-Villalba et al., Reference Trautmann-Villalba, Gschwendt, Schmidt and Laucht2006; Wilson & Durbin, Reference Wilson and Durbin2010). Though evidence is weaker and less consistent, some work has found that negative parenting practices may also mediate the association between paternal depression and child psychopathology (Gutierrez-Galve et al., Reference Gutierrez-Galve, Stein, Hanington, Heron and Ramchandani2015; Sethna et al., Reference Sethna, Murray, Netsi, Psychogiou and Ramchandani2015; Sweeney & MacBeth, Reference Sweeney and MacBeth2016). Together, prior research suggests that paternal depression increases child psychopathology through primarily indirect, contextual mechanisms (Gutierrez-Galve et al., Reference Gutierrez-Galve, Stein, Hanington, Heron and Ramchandani2015; Sweeney & MacBeth, Reference Sweeney and MacBeth2016), while maternal depression impacts children more directly, through parenting behaviors (i.e., decreased sensitivity and responsivity, and coercive parenting), modeling, and negative attachment style (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Keller and Davies2005; Lovejoy et al., Reference Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare and Neuman2000; Sohr-Preston & Scaramella, Reference Sohr-Preston and Scaramella2006; Sweeney & MacBeth, Reference Sweeney and MacBeth2016). Thus, maternal and paternal depression may uniquely impact children’s psychopathology.

Reciprocal effects of child and parent psychopathology

Although associations between parental depression and children’s psychopathology are well established, far less is known about causal effects of children’s emotions and behaviors on their parent’s mental health. Sameroff’s (Reference Sameroff1975, Reference Sameroff2009) transactional model of development posits that children both shape and are shaped by their context continuously and over time. In families, children are thought to elicit patterns of behaviors and reactions from their parents, who in turn elicit behaviors and reactions from their children and one another (Ding et al., Reference Ding, Lin, Hinshaw, Liu, Tan and Meza2022; Neri et al., Reference Neri, Giovagnoli, Genova, Benassi, Stella and Agostini2020; Paulson & Bazemore, Reference Paulson and Bazemore2010; Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2009). These dynamic processes have significant implications for each family member’s psychological well-being. One possible mechanism that may explain these effects is the tendency for children’s expressions of emotion and behavior dysregulation (e.g., crying and tantrums) to overwhelm the emotional capacity of their parents, causing distress, and eliciting coercive parenting behaviors (i.e., irritable, critical, and harsh parenting) that in turn exacerbate internalizing and externalizing problems in children (e.g., conduct problems and emotion dysregulation) (Felton et al., Reference Felton, Schwartz, Oddo, Lejuez and Chronis-Tuscano2021; Hails et al., Reference Hails, Reuben, Shaw, Dishion and Wilson2018; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Dudgeon, Sheeber, Yap, Simmons and Allen2011). Decreased family cohesion and increased family conflict resulting from children’s internalizing and externalizing problems may also compromise the marital relationship and deplete parents’ coping resources, leading to greater parental depression and more negative parenting behaviors (Elgar et al., Reference Elgar, Curtis, McGrath, Waschbusch and Stewart2003; Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Panayiotou and Fanti2013; Gross et al., Reference Gross, Shaw, Moilanen, Dishion and Wilson2008; Hails et al., Reference Hails, Reuben, Shaw, Dishion and Wilson2018; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Simpson, Flannery and Ohannessian2019). Thus, there is theoretical support for the effects of children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms on their parent’s depression.

A burgeoning literature has investigated reciprocal associations between maternal depression and children’s psychopathology and has found mixed results. While maternal depressive symptoms prospectively increased depression in young children and adolescent, youth psychopathology also led to greater maternal depression from childhood through adolescence (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Manning and Meyer2010; Bagner et al., Reference Bagner, Pettit, Lewinsohn, Seeley and Jaccard2013; Baker et al., Reference Baker, Brooks-Gunn and Gouskova2020; Elgar et al., Reference Elgar, Curtis, McGrath, Waschbusch and Stewart2003; Gross et al., Reference Gross, Shaw, Moilanen, Dishion and Wilson2008; Hails et al., Reference Hails, Reuben, Shaw, Dishion and Wilson2018; Hughes & Gullone, Reference Hughes and Gullone2010; Jaffee & Poulton, Reference Jaffee and Poulton2006; Roubinov et al., Reference Roubinov, Epel, Adler, Laraia and Bush2022; Wiggins et al., Reference Wiggins, Mitchell, Stringaris and Leibenluft2014). In contrast, some studies found that while maternal depression increased child internalizing symptoms, child symptoms did not predict increased maternal depression (Cioffi et al., Reference Cioffi, Leve, Natsuaki, Shaw, Reiss, Ganiban and Neiderhiser2021; Mennen et al., Reference Mennen, Negriff, Schneiderman and Trickett2018; Paquin et al., Reference Paquin, Castellanos-Ryan, Vitaro, Côté, Tremblay, Séguin, Boivin and Herba2020; Tyrell et al., Reference Tyrell, Yates, Reynolds, Fabricius and Braver2019; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Ansari and Peng2021). Furthermore, one study found that adolescent’s internalizing symptoms increased maternal depression, while maternal depression was not associated with adolescent symptoms (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Chen and Guo2020). The few studies examining reciprocity between paternal depression and children’s psychopathology have not found support for reciprocal associations between father depression and child internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Manning and Meyer2010; Cioffi et al., Reference Cioffi, Leve, Natsuaki, Shaw, Reiss, Ganiban and Neiderhiser2021; Gross et al., Reference Gross, Shaw, Moilanen, Dishion and Wilson2008; Tichovolsky et al., Reference Tichovolsky, Griffith, Rolon-Arroyo, Arnold and Harvey2018; Tyrell et al., Reference Tyrell, Yates, Reynolds, Fabricius and Braver2019).

Parental depression and cognition

Although some research has evaluated the effects of parental depression on children’s cognitive development, findings have been inconsistent, and no study has evaluated reciprocal associations between child cognition and parental depression. Maternal and paternal depression have been associated with risk for cognitive and language problems in their young children (Ahun & Côté, Reference Ahun and Côté2019; Harewood et al., Reference Harewood, Vallotton and Brophy-Herb2017; Herbert et al., Reference Herbert, Harvey, Lugo-Candelas and Breaux2013; McManus & Poehlmann, Reference McManus and Poehlmann2012) and with cognitive outcomes in middle childhood (i.e., age 5–8 years; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Melotti, Heron, Ramchandani, Wiles, Murray and Stein2012; Hay et al., Reference Hay, Asten, Mills, Kumar, Pawlby and Sharp2001). Depressed parents are less likely to engage interactively with their children (e.g., play and reading to children) and tend to be less responsive caregiving, leading to a dearth of stimulating input and consistent emotional support, both of which are known risk factors for the development of core cognitive abilities, particularly language, and executive functioning (Grantham-McGregor et al., Reference Grantham-McGregor, Cheung, Cueto, Glewwe, Richter and Strupp2007; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Wachs, Meeks Gardner, Lozoff, Wasserman, Pollitt and Carter2007). Parental depression, and associated increases in harsh and unresponsive parenting, has also been conceptualized as a powerful stressor in early childhood associated, which has been shown to compromise brain development and complex cognitive functions (i.e., executive functioning, language, and problem-solving) (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Yang, Zheng, Song and Yi2021). A review found that family stress and maternal negative parenting (negative maternal affect, low sensitivity/responsiveness) partially mediated the association between maternal depression and poorer child cognition (Ahun & Côté, Reference Ahun and Côté2019). While both mother’s and father’s postnatal depression has been found to predict decreased engagement in activities promoting healthy cognition (e.g., reading, singing songs and telling stories; Paulson et al., Reference Paulson, Keefe and Leiferman2009), studies have also reported differential effects of maternal and paternal depression on children’s cognitive outcomes. Paternal depression has been found to predict poorer expressive language development and children’s complex response inhibition at age 2 (Malin et al., Reference Malin, Karberg, Cabrera, Rowe, Cristaforo and Tamis-LeMonda2012; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Caughy, Hurst, Amos, Hasanizadeh and Mata-Otero2013; Paulson et al., Reference Paulson, Keefe and Leiferman2009) while maternal depression predicts poorer simple response inhibition (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Caughy, Hurst, Amos, Hasanizadeh and Mata-Otero2013). The extant work supports detrimental effects of parental depression on children’s cognition, with some support for different influences of maternal and paternal depression on children’s cognitive functioning. Discrepancies in findings from prior studies may be explained by the diversity of cognitive measures used across studies, differences in children’s ages when measured, or the demographic composition of the samples (Ahun & Côté, Reference Ahun and Côté2019). Studies using broad measure of cognition that capture numerous domains of cognitive functioning may be able to detect detrimental effects of maternal depression on many different areas of cognition while studies using specific measures (e.g., receptive vocabulary) may not find effects on a domain of cognition that is not captured in a narrower measure. Furthermore, significant research supports the conceptualization of early childhood cognition in terms of broader, latent constructs (e.g., executive functioning, and verbal and nonverbal processing), lending support to the use of broad cognitive measures in studies of early childhood cognitive development (Bussu et al., Reference Bussu, Taylor, Tammimies, Ronald and Falck-Ytter2023; Decker et al., Reference Decker, Ezrine and Ferraracci2016; Wiebe et al., Reference Wiebe, Espy and Charak2008). This study addresses these gaps in prior literature by evaluating effects of parental depression on a measure of broad cognitive functioning that captures numerous domains associated with parental depression (e.g,. executive functioning, language, and perceptual processing; Malin et al., Reference Malin, Karberg, Cabrera, Rowe, Cristaforo and Tamis-LeMonda2012; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Caughy, Hurst, Amos, Hasanizadeh and Mata-Otero2013; Paulson et al., Reference Paulson, Keefe and Leiferman2009; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Yang, Zheng, Song and Yi2021).

Taken together, prior literature provides some support for reciprocal influences between parental depression and children’s mental health and unidirectional, negative effects of parental depression on child cognitive outcomes. No study, however, has examined reciprocal pathways between parental depression and children’s cognition. This is crucial given the transactional nature of children’s and parents’ psychological functioning, and the transdiagnostic importance of cognitive functioning (Craik & Bialystok, Reference Craik and Bialystok2006; Heckman, Reference Heckman2006).

The current study

The present study addressed this gap by using structural equation modeling to examine reciprocal associations between parental depression and children’s cognition (e.g., social-emotional development, problem-solving, memory, and language) and pathways to later children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. We examined these models in a sample of 3,001 youth from ages 14 months to 10–11 years as part of the Early Head Start Research and Evaluation (EHSRE) study. We hypothesized that maternal depression, paternal depression, and children’s cognition would influence one another reciprocally from 14 months old to age 5, such that greater parental depression would predict decreased child cognition at subsequent time points, and vice versa. We also hypothesized that pathways would emerge linking parental depression and child cognition at 14 months to internalizing and externalizing symptoms at age 10–11, though we did not develop hypotheses about specific pathways given the dearth of existing evidence. Finally, as an exploratory aim, the present study explored the moderating role of race/ethnicity in reciprocal pathways between child cognition, parental depression, and child psychopathology. Experiences of oppression and discrimination in minoritized families increase the allostatic load, and the vulnerability of both parents and children to cognitive and emotional problems (Okeke et al., Reference Okeke, Elbasheir, Carter, Powers, Mekawi, Gillespie, Schwartz, Bradley and Fani2023; Zare et al., Reference Zare, Najand, Fugal and Assari2023). It is therefore possible that pathways between parental depression, child cognition, and later psychopathology might differ according to the racial/ethnic identity of the family.

Methods

Participants

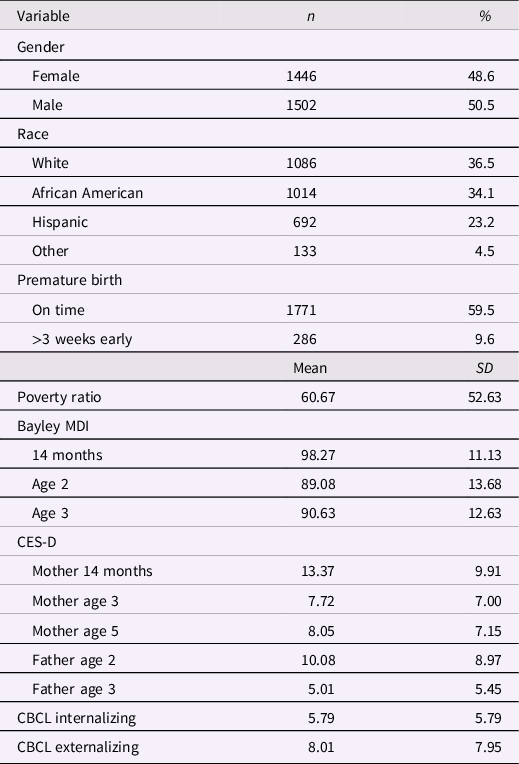

This study utilized a public data set from the EHSRE study and the supplemental father study. This data set includes a nationally representative sample of families from 17 US communities who met eligibility criteria to enroll in Early Head Start, a service that provides support for expecting families through preschool, from 1996 to 2010 (United States Department of Health and Human Services. Administration for Children and Families, 2004). The EHSRE project recruited families with a primary caregiver either expecting a child or caring for a child younger than 1 year old who had incomes at or below the US federal poverty level and/or a child with a disability. Participants included in the analytic sample were 2,951 children and their parents who completed a battery of assessment questionnaires (see Measures below) at the 14-month, 24-month, and 36-month time points. Child sex was coded as male (50.5%) or female (48.6%). Primary caregivers reported to identify with the following racial groups: 36.5% White, 34.1% African American, 23.2% Hispanic, and 4.5% other. Children born more than 3 weeks early were labeled as an early birth (9.6%). The average poverty ratio, recorded as income data as percent of poverty line, multiplied by ten, and divided by the poverty line in the relevant year for the family household size, was 60.67 (SD = 52.63), indicating the average participant was living at 39.33% below the poverty line for the relevant year in which their data was collected (see Table 1 for sample and study variable statistics).

Table 1. Demographics characteristics of participants and descriptive statistics of study variables

Note. BSID MDI = Bayley Scales of Infant Development Mental Development Index; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CESD-SF = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Short Form; CBCL = Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment Child Behavior Checklist.

Procedures

Data were collected from families in their homes. Six data waves were collected according to the age of the child as part of the EHSRE study. The first time point, Wave 1, took place when the children were 14 months, Wave 2 at age 2, Wave 3 at age 3, Wave 4 before the child’s kindergarten at approximately age 5, and Wave 5 at approximately age 10–11, when the child was in 5th grade. Child and family information, including income, family circumstances, and child medical history, was collected at baseline. As a supplement to the EHSRE study, fathers from 12 of the 17 sites participated in interviews and videotaped measures when children were age 2 and 3.

Measures

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

Parental depression was measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, Reference Radloff1977), a 20-item questionnaire that assesses caregivers’ symptoms associated with depression experienced within the past week. Maternal depression was measured at 14 months, age 3, and age 5 and paternal depression measured at age 2 and age 3. Symptoms assessed include diminished appetite, restless sleep, loneliness, sadness, and lack of energy. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 Rarely or None of the Time to 2 Moderately or Much of the Time. Scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating higher frequency of depressive symptoms. The CES-D has demonstrated high convergent validity with other widely used measures measuring depressive symptoms (r = .85; Amtmann et al., Reference Amtmann, Kim, Chung, Bamer, Askew, Wu, Cook and Johnson2014; Roberts, Reference Roberts1980; Shean & Baldwin, Reference Shean and Baldwin2008). The CES-D demonstrates good to excellent internal consistency for this sample across racial and ethnic groups for 14 months (White; α = .90, African American; α = .90, Hispanic; α = .90), 36 months (α = .88), age 5 (α = .88), and age 10–11 (all; α = .87, White; α = .88, African American; α = .84, Hispanic; α = .89) (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Kemmerer, West and Lim2016).

Bayley Scales of Infant Development

Child cognition was measured at 14 months, age 2, and age 3 using the Bayley Scales of Infant Development Mental Development Index (BSID MDI; Bayley, Reference Bayley1993), a norm-referenced assessment that measures the cognitive, language, and personal-social development of children under age 3½ (Bayley, Reference Bayley1993). For the purposes of this study, cognition was the only scale included in the analysis. The Mental Developmental Index measures social-emotional development, sensory perception, knowledge, memory, problem-solving, and early language skills (Bayley, Reference Bayley1993; Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Erickson, Schrader and Duncan2012). Early Head Start administration and scoring procedures followed the Bayley Scales of Infant Development Manual, Second Edition. The BSID MDI yields an age-standardized score ranging from 50 to 150, with a score of 49 designated to children who did not meet the basal criteria indicative of severely delayed development (Koseck, Reference Koseck1999). The BSID-II demonstrates good to excellent internal consistency for 14 months (α = .86), age 2 (α = .92), and age 3 (α = .89) (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Kemmerer, West and Lim2016).

Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment, Child Behavior Checklist

Child internalizing and externalizing behaviors were measured at age 10–11 using the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment, Child Behavior Checklist For Ages 1½–5 (CBCL 1.5–5; Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2000), a 99-item parent reported questionnaire used to assess a broad range of problems in children. Items are coded on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 0 Not True to 2 Very True or Often True. The CBCL 1.5–5 has demonstrated very good psychometrics across test–retest reliability, construct validity, and criterion validity (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2001; Ha et al., Reference Ha, Kim, Song, Kwak and Eom2011; Ivanova et al., Reference Ivanova, Achenbach, Rescorla, Harder, Ang, Bilenberg, Bjarnadottir, Capron, De Pauw, Dias, Dobrean, Doepfner, Duyme, Eapen, Erol, Esmaeili, Ezpeleta, Frigerio, Gonçalves and Verhulst2010; Pandolfi et al., Reference Pandolfi, Magyar and Dill2009). The Internalizing composite scores, comprised of the Emotionally Reactive, Anxious/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, and Withdrawn subscales, and the Externalizing composite scores, comprised of Attention Problems and Aggressive Behavior subscales, were used for the purposes of this analysis. The CBCL 1.5–5 Internalizing Behavior subscale demonstrated good internal consistency for this sample across racial and ethnic groups (all; α = .85, White; α = .86, African American; α = .85, Hispanic; α = .83) (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Kemmerer, West and Lim2016). The CBCL 1.5–5 Externalizing Behavior subscale demonstrated good to excellent internal consistency for this sample across racial and ethnic groups (all; α = .91, White; α = .92, African American; α = .91, Hispanic; α = .88) (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Kemmerer, West and Lim2016). Internalizing and Externalizing subscales demonstrated the ability to discriminate between children with and without an anxiety disorder and discriminate between children with an anxiety disorder and an externalizing disorder (Seligman et al., Reference Seligman, Ollendick, Langley and Baldacci2004).

Data analyses

Analyses were conducted with the statistical package Mplus Version 8.5 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2017) utilizing bootstrapping technique with 500 bootstrap samples. Missingess across waves were previously examined by Carlson (Reference Carlson2009) by comparing characteristics of the respondents at Wave 1 with the characteristics of respondents at Wave 3 and Wave 5. After comparing the distributions of 34 individual characteristics, the results revealed no significant differences between Wave 1 and Wave 3 and between Wave 1 and Wave 5 after correcting for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction (all p-values > .0015), suggesting these data are missing at random. Maximum likelihood estimation was therefore utilized in the current study to model missing data. Maximum likelihood estimation has been shown to be superior at producing unbiased parameter estimates and standard errors than other missing data methods (e.g., listwise deletion, pairwise deletion, and similar response pattern imputation) for structural equation models when data is missing at random (Enders & Bandalos, Reference Enders and Bandalos2001).

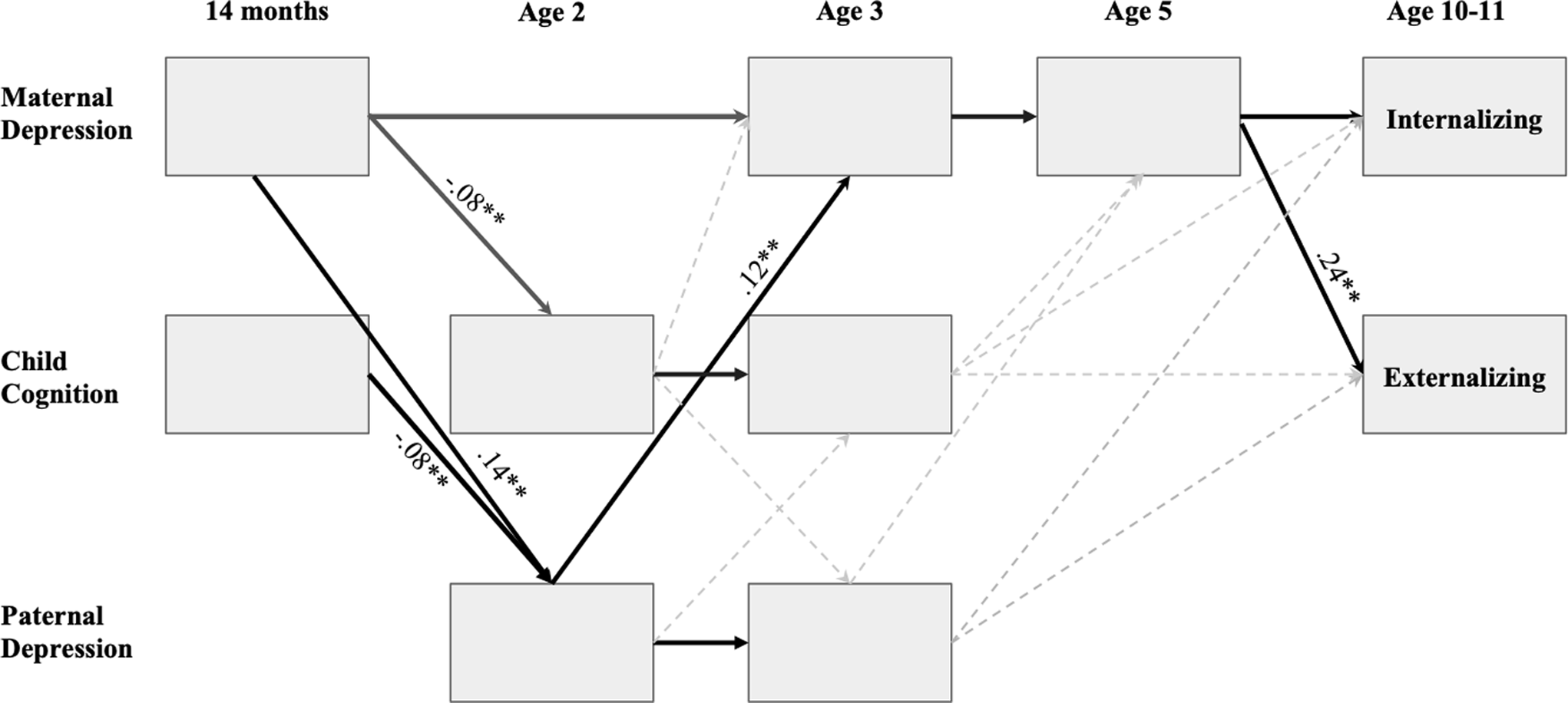

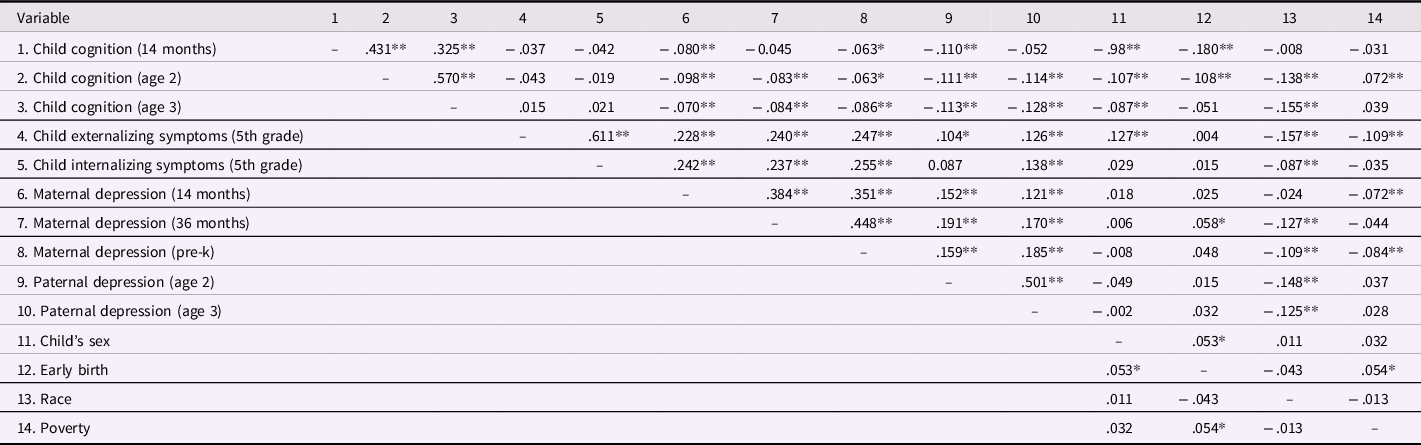

A structural equation model was used to examine the reciprocal paths between paternal depression, maternal depression, child cognition, and child internalizing and externalizing symptoms across five timepoints (i.e., the child at 14 months, at age 2, at age 3, at age 5, and at age 10–11). In the model, data from all measures at the different timepoints were entered simultaneously. Specifically, 14 direct paths and 11 indirect paths were entered in the model. The direct paths include: (1) and (2) maternal depression at 14 months predicting child cognition and paternal depression at age 2; (3) and (4) maternal depression at age 5 predicting child internalizing and externalizing symptoms at age 10–11; (5) and (6) paternal depression at age 2 predicting child cognition and maternal depression at age 3; (7), (8), and (9) paternal depression at age 3 predicting maternal depression at age 5 and child internalizing and externalizing symptoms at age 10–11; (10) and (11) child cognition at age 2 predicting maternal depression and paternal depression at age 3; and (12), (13), and (14) child cognition at age 3 predicting maternal depression at age 5 and child internalizing and externalizing symptoms at age 10–11. The indirect paths include: (1), (2), (3), and (4) child cognition at 14 months predicting paternal depression at age 3, maternal depression at age 5, child internalizing and externalizing symptoms at age 10–11; (5), (6), (7), and (8) maternal depression at 14 months predicting child cognition at age 2, paternal depression at age 3, and child internalizing and externalizing symptoms at age 10–11; (9), (10), and (11) paternal depression at age 2 predicting paternal depression at age 4 and child internalizing and externalizing depression at age 10–11. Stability paths were included for paternal depression, maternal depression, and child cognition across the five timepoints (see Figure 1 depicting the structural equation model). In our analyses, we controlled for children’s sex, given robust evidence of sex differences in cognitive development and psychopathology (Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Hahn and Haynes2004; Cox & Paley, Reference Cox and Paley2003) and impacts of premature birth on cognitive development (Macey et al., Reference Macey, Harmon and Easterbrooks1987; Masten & Garmezy, Reference Masten, Garmezy, Lahey and Kazdin1985) (see Table 2 for correlations between study variables). Model fit was examined by the comparative fit index (CFI), the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standard root mean square residual (SRMR). Generally, CFI values greater than .90, RMSEA and SRMR values equal to or lower than .08 indicate acceptable fit (Keith, Reference Keith2019). Model fit was not determined utilizing X2 due to the large sample size and the sensitivity of the X2 to sample size.

Figure 1. Path analysis model of parent depression, child cognition, and psychopatholog. Note. All estimates are standardized. Bolded arrows depict indirect effects. Dashed lines represent nonsignificant pathways. Covariances are not shown in this figure but were included between all variables measured in the same assessment wave. Stability pathways were not included in the model unless part of an indirect pathway. *p < .05; **p<01.

Table 2. Bivariate correlation between child cognition, child externalizing and internalizing symptoms, and parental depression

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01.

An exploratory model examined the child’s race/ethnicity as a moderator of pathways using multi-group analyses. All paths were constrained to be equal across groups (African American, White, Hispanic, and Other). The fit of the initial model was then compared to the fit of a new model in which all estimated paths, variances, and covariances were free to vary across groups. The chi-square difference test was used to determine that there was no significant improvement in model fit. This indicated that no paths were significantly moderated by group (i.e., child race/ethnicity).

Results

Model fit

The structural equation modeling reciprocal paths between parental depression and child cognition exhibited excellent model fit: X2 (33, N = 2,951) = 158.58, p < .001, CFI = .956, RMSEA = .036, and SRMR = .036.

Direct effects

Greater maternal depression at 14 months predicted lower child cognition at age 2 (β = −.078, SE = .023, p < .001) and greater paternal depression at age 2 (β = .155, SE = .049, p = .002). Additionally, greater maternal depression at age 5 predicted greater child internalizing symptoms (β = .254, SE = .033, p < .001) and greater child externalizing symptoms at age 10–11 (β = .248, SE = .030, p < .001). Finally, greater paternal depression at age 2 predicted greater maternal depression at age 3 (β = .102, SE = .037, p = .005). All direct effects were estimated while controlling for the child’s sex and the family’s poverty ratio. No other direct effects were significant.

Indirect effects

Parental depression and child internalizing symptoms

Greater maternal depression at 14 months predicted higher levels of child internalizing symptoms via two pathways: (1) greater maternal depression at age 3 led to greater maternal depression at age 5 (β = .085, 95% CI [.065, .110]) and (2) greater paternal depression at age 2 led to greater maternal depression at age 3, which subsequently led to greater maternal depression at age 5 (β = .004, 95% CI [.002, .008]). Furthermore, greater paternal depression predicted higher levels of child internalizing symptoms via greater maternal depression at age 3, which led to greater maternal depression at age 5 (β = .023, 95% CI [.011, .041]).

Parental depression and child externalizing symptoms

Greater maternal depression at 14 months predicted higher levels of child externalizing symptoms at age 10–11 via three pathways: (1) greater maternal depression at age 3 led to greater maternal depression at age 5 (b = .083, 95% CI [.062, .105]) and (2) greater paternal depression at age 2 led to greater maternal depression at age 3, and subsequent greater maternal depression at age 5 (b = .004, 95% CI [.001, .008]). Furthermore, greater paternal depression at age 2 predicted greater child externalizing symptoms at age 10–11 via greater maternal depression at age 3, which led to greater maternal depression at age 5 (b = .023, 95% CI [.010, .038]).

Parental depression and child cognition

Lower child cognition at 14 months predicted greater maternal depression at age 5 via paternal depression at age 2, which led to greater maternal depression at age 3 (β = −.007, 95 CI [−.022, −.002]). Additionally, lower child cognition at 14 months also predicted greater paternal depression at age 3 via greater paternal depression at age 2 (β = −.061, 95% CI [−.138, −.008]). Finally, greater maternal depression at 14 months led to lower child cognition at age 3 via lower child cognition at age 2 (β = −.046, 95% CI [−.070, −.023]).

Maternal and paternal depression

Greater maternal depression at 14 months predicted greater paternal depression at age 3 via greater paternal depression at age 2 (β = .120, 95% CI [.037, .202]). The reciprocal effect was also significant: greater paternal depression at age 2 predicted greater maternal depression at age 5 via greater maternal depression at age 3 (β = .106, 95% CI [.061, .170]).

Moderation of path models by race/Ethnicity

Results from the multi-group analysis indicated that the initial model in which pathways were constrained to be equal across racial/ethnic group, X2 (237, n = 2,919) = 495.58, p < .001, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .04, and SRMR = .07, was not significantly different from the model in which pathways were free to vary by race, X2 (188, n = 2,919) = 478.57, p < .001, CFI = .90, RMSEA = .03, and SRMR = .05, according to a chi-square difference test, ΔX2 (49) = 17.02, p > .05.

Discussion

The present study was the first to investigate reciprocal associations between children’s cognition, maternal depression, and paternal depression across early childhood, and associations with later internalizing and externalizing symptoms in middle childhood. Results showed that children’s cognition, and both mother’s and father’s depression in early childhood, significantly predicted children’s externalizing and internalizing symptoms in middle childhood, and that these pathways were mediated by co-parent depression. Contrary to hypotheses, we did not find reciprocal associations between maternal or paternal depression and children’s cognition. We did, however, find that mother’s depression at 14 months old led to poorer cognition at age 3 through cognition at age 2, and that cognition at 14 months old led to decreased father’s depression at age 3 through father’s depression at age 2.

Parent depression and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms

We found that maternal depression at 14 months predicted greater child internalizing and externalizing symptoms at age 10–11 through multiple pathways: first, through greater maternal depression from age 3 to age 5, and second, through greater paternal depression at age 2 which in turn increased maternal depression at age 3 to age 5. Paternal depression at age 2 predicted children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms through greater maternal depression at age 3 to age 5. Overall, we found reciprocal relations between maternal depression and paternal depression from 14 months to age 5 years old; these pathways predicted youth internalizing and externalizing psychopathology when children were 10–11 years old. These findings, along with our findings of reciprocal relations among maternal and paternal depression across development, are consistent with theoretical models which posit that depressed marital partners elicit reassurance and negative feedback from one another, leading to a cycle of frustration and unsupportiveness, in turn increasing risk for depression in each partner and their children (Connell & Goodman, Reference Connell and Goodman2002; Gutierrez-Galve et al., Reference Gutierrez-Galve, Stein, Hanington, Heron and Ramchandani2015; Joiner & Katz, Reference Joiner and Katz1999; Ramchandani et al., Reference Ramchandani, Stein, O’Connor, Heron, Murray and Evans2008). Prior work has also demonstrated that increased paternal depression is associated with increased maternal depression (Ding et al., Reference Ding, Lin, Hinshaw, Liu, Tan and Meza2022; Edward et al., Reference Edward, Castle, Mills, Davis and Casey2015; Elgar et al., Reference Elgar, Curtis, McGrath, Waschbusch and Stewart2003; Paulson & Bazemore, Reference Paulson and Bazemore2010).

Parent depression and children’s cognition

This study is the first longitudinal study to examine effects of children’s cognition (e.g., social-emotional development, problem-solving, memory, and language) on their parents’ depression over time. Poorer child cognition at age 14 months predicted greater maternal depression at age 5 through greater paternal depression at age 2, which led to greater maternal depression at age 3. Similarly, poorer child cognition at 14 months predicted greater paternal depression at age 3 through paternal depression at age 2. Although no prior study has specifically examined effects of cognition on parent depression, these findings are consistent with prior research demonstrating negative impacts of young children’s behavioral problems (e.g., poor affect and behavioral regulation), which are associated with poor cognition, on parent’s depressive symptoms (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Brooks-Gunn and Gouskova2020; Gross et al., Reference Gross, Shaw, Moilanen, Dishion and Wilson2008; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Ansari and Peng2021). Children with poorer cognitive functioning and behavioral problems may be more difficult to soothe and may elicit negative parenting behaviors, in turn increasing distress and depressed mood in parents (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Brooks-Gunn and Gouskova2020; Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Goeke-Morey and Raymond2004). Interestingly, our pattern of findings indicated that while poorer child cognition increased paternal depression, regardless of maternal depression, poorer child cognition increased maternal depression only through paternal depression. This aligns with prior research demonstrating that mothers are able to compartmentalize their parenting-related stress and depressive behaviors more effectively than fathers, which may protect mothers, but not fathers, from direct impacts of their children’s cognition on their mood and behavior (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Goeke-Morey and Raymond2004).

In addition, our findings on the complex and bidirectional influences of psychopathology and functioning between family members lends support to transactional models of childhood development which highlights the dynamic processes through which children and their parents shape one another’s psychological functioning across development (Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2009). Given the dearth of prior research on reciprocal associations between children’s cognition and parent depression, our findings provide insight into the transactional pathways through which impaired cognitive functioning in young children impact parent depression and later psychopathology.

Consistent with prior literature, we also found that maternal depression, but not paternal depression, negatively impacted children’s cognition (Ahun & Côté, Reference Ahun and Côté2019; McManus & Poehlmann, Reference McManus and Poehlmann2012). Although this finding is in line with prior work suggesting that maternal depression is a more salient risk factor than paternal depression for a range of developmental outcomes in early childhood (Connell & Goodman, Reference Connell and Goodman2002; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Chen and Guo2020; Ramchandani et al., Reference Ramchandani, Stein, O’Connor, Heron, Murray and Evans2008; Tyrell et al., Reference Tyrell, Yates, Reynolds, Fabricius and Braver2019), this finding contrasts with a few studies, which have found that that paternal depression is a stronger predictor of externalizing symptoms than maternal depression (Connell & Goodman, Reference Connell and Goodman2002; Kane & Garber, Reference Kane and Garber2004), and a risk factor for poorer childhood cognition (e.g., language development and inhibition), independent of maternal depression (Harewood et al., Reference Harewood, Vallotton and Brophy-Herb2017; Herbert et al., Reference Herbert, Harvey, Lugo-Candelas and Breaux2013; Wanless et al., Reference Wanless, Rosenkoetter and McClelland2008).

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study included the longitudinal, repeated measures design in which parent depression and children’s cognition was measured at 4 time points in early childhood. This design allowed us to study the reciprocal influences of parents and children on one another, and the complex interplay of parent depression and child cognition from year to year, from 14 months old to age 5 and psychopathology through middle childhood. Second, our use of paternal depression data in combination with maternal depression in our model illuminated differential and transactional effects of mother and father depression on their children. Despite growing interest in the importance of fathers for children’s development, research on the additive and independent effects of paternal depression on children’s development is still scarce compared to studies of maternal depression, particularly in models evaluating cognition and later psychopathology. Third, our use of a comprehensive, standardized measure of children’s cognition, completed each year from 14 months old to age 3, allowed us to study effects of children’s cognition on their parent’s depression across time, which, to the best of our knowledge, is the first investigation of this question. Fourth, given the underrepresentation of culturally diverse families in psychological research, our results provide key insights into influences of parental depression on child cognitive development in a diverse sample that accurately reflects the growing number of marginalized youth in the USA (Tindle, Reference Tindle2021). We did not find differences in associations between childhood cognition and parental depression by racial group in this sample. Nevertheless, additional research should explore this question in families with a wider range in socioeconomic status and depressive symptoms to understand whether or not these differences might emerge when parents are experiencing greater levels of depression or lower levels of poverty.

Several limitations were noted in our study. Father depression data was only available at two time points (2 years and 3 years), which limited our ability to determine effects of paternal depression on children’s cognition at the earlier time point available for maternal depression (14 months old). In addition, our lack of data from fathers at all timepoints prevented us from using a random-intercept cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM), which would have allowed us to disentangle within- and between-person effects. Future work that measures maternal and paternal depression and child cognition repeatedly across early childhood should employ a RI-CLPM (Hamaker et al., Reference Hamaker, Kuiper and Grasman2015) to evaluate the early emergence of reciprocal influences between parental depression and child cognition, and to disentangle within- and between-person effects.

Conclusions

The present study offers novel insight into the detrimental effect of poor child cognition on paternal depression, and transactional effects of maternal and paternal depression in predicting their children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Our findings lend support to the field’s growing emphasis on understanding child to parent effects in addition to parent to child effects. Results have important implications for intervention and prevention efforts, indicating that supporting cognitive development, through early enrichment and education programs, is a useful target of intervention to reduce mental health problems in both children and their parents. Our findings demonstrating the transactional patterns between parents and children suggest that interventions efforts should target contextual, family factors (e.g., parent–child interactions and parental conflict) early in development. Such early prevention and intervention efforts would help to protect early childhood cognition and subsequent mental health in both. In addition, results regarding the reciprocity of mother’s and father’s depression and the detrimental effects of these dynamics on children’s later mental health support family integrated interventions that target parents’ mental health. Promoting self-care and emotional well-being in parents, particularly parents of young children, may serve to alleviate transmission of psychopathology both between parents and to their children.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author contribution

All authors have materially participated in the research and/or article preparation. My co-authors have reviewed this manuscript. I have assumed responsibility for keeping them informed throughout the review process. In addition, although I have full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses, each author has participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content.

Funding statement

The Early Head Start Research and Evaluation project was funded by the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation in the Administration of Children of Families grant number 105-95-1936.

Competing interests

None.