Harm reduction is an umbrella term used for a set of ideas, interventions and practical strategies aimed at reducing negative consequences associated with substance use and other health behaviours.Reference Clear, Springer and Lanier1 Although the concept of harm reduction has existed for a long time, its formalisation started during 1980s in the context of the HIV epidemic, propelled by opioid use among those with injecting drug use, and later expanded to many other substances. In the context of opioids, the evidence-based harm reduction strategies include opioid agonist treatment, needle and syringe programmes, safe injection rooms, overdose prevention programmes, fentanyl strips, identification and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases, outreach and education. Such interventions have been found to be highly effective and remained the mainstay of treatment for opioid use disorders. Abstinence refers to complete cessation of substance use. The DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders (SUDs) uses cut-offs of 3 and 12 months for early and sustained remission respectively. In general, abstinence-based models have dominated treatment programmes globally and have been an inherent component of residential programmes (e.g. therapeutic communities) and twelve-step facilitation.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought unprecedented challenges for individuals with SUDs and health professionals involved in their care. There were changes related to policy, availability of substances, patterns of use, substance-related complications and the provision of treatment services. In this brief review we discuss changes in harm reduction and abstinence-based approaches during the COVID-19 pandemic, based on perspectives from health professionals in eight countries and supplemented by data from global surveys of professionals involved in substance use treatment services conducted during the pandemic.

Impact of COVID-19 on treatment services

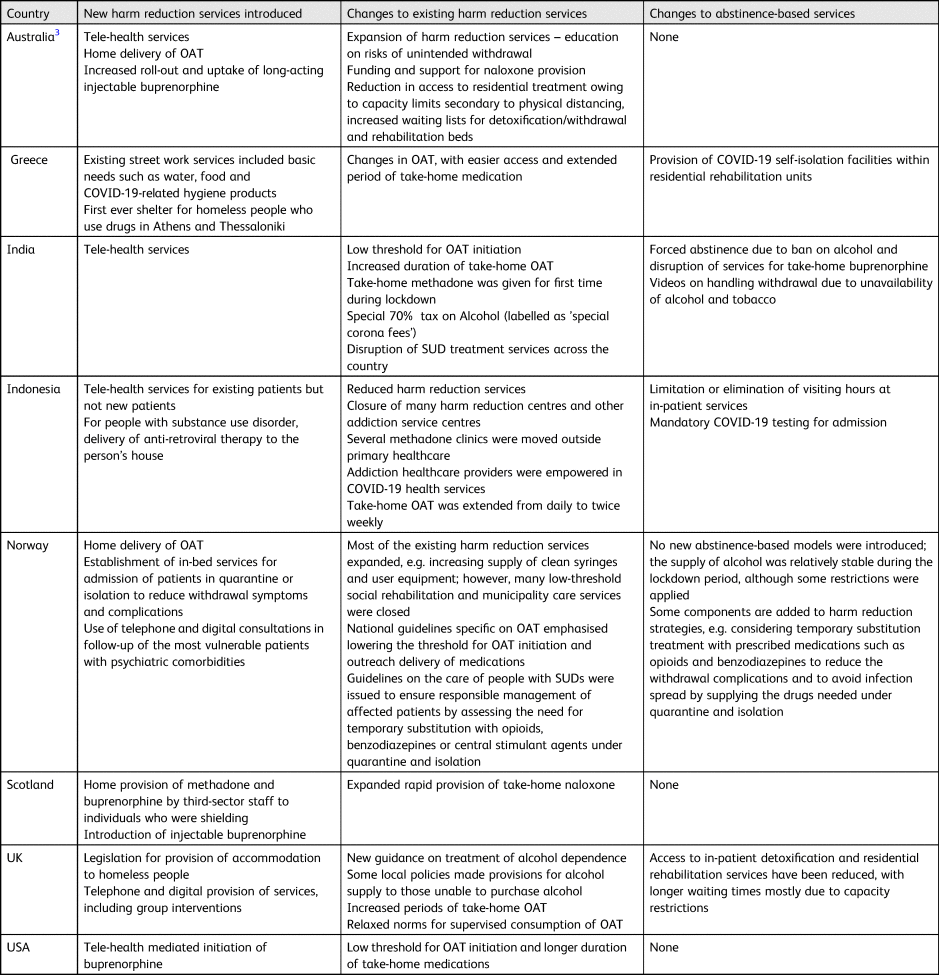

During the COVID-19 pandemic, people with SUDs and their access to services were significantly affected across the world (Table 1).Reference Kouimtsidis, Pauly, Parkes, Stockwell and Baldacchino2 Aglobal survey during the initial months of the pandemic by the International Society of Addiction Medicine Practice and Policy Interest Group (ISAM-PPIG) observed a worldwide impact on SUD treatment and harm reduction services. Importantly, professionals in one-third of countries reported a shortage of methadone and buprenorphine supplies, and around 40% of countries witnessed a rapid decrease in harm reduction services, especially needle and syringe programmes and condom distribution. Professionals in more than half of the countries reported an impact on overdose prevention services, and around 80% reported that outreach services were affected.Reference Radfar, De Jong, Farhoudian, Ebrahimi, Rafei and Vahidi4 Service providers in low-income countries described significant impacts due to sudden policy changes, lack of transportation, reduction of emergency room beds and disruption of out-patient services.Reference Farhoudian, Radfar, Mohaddes Ardabili, Rafei, Ebrahimi and Khojasteh Zonoozi5 A second global survey by ISAM-PPIG conducted later in the pandemic observed changes in drug availability, safety and consumption patterns in early phases of lockdown due to COVID-19. Many countries reported reductions in drug supply, with an increase in the illicit market price of drugs. During the pandemic, some countries experienced an increase in fentanyl use among those on opioid agonist treatment and reported an increase in fentanyl-related overdoses.Reference Macmadu, Batthala, Correia Gabel, Rosenberg, Ganguly and Yedinak6,Reference Morin, Acharya, Eibl and Marsh7 Overall, while the consumption of alcohol, cannabis, prescription opioids, and sedatives increased, there was a reduction in use of amphetamine, cocaine and illicit opiates.Reference Farhoudian, Radfar, Mohaddes Ardabili, Rafei, Ebrahimi and Khojasteh Zonoozi5 The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) also reported reduced activity in treatment services the during first 2 months of the pandemic and normalisation after June 2020.8 Additionally, it noted an increase in treatment demand, posing challenges for healthcare services. Similarly, access to abstinence-based approaches was disrupted as there was a reduction in the number of service providers and longer waiting times to access services.

Table 1 Changes in harm reduction and abstinence-based services across eight countries

OAT, opioid agonist treatment; SUD, substance use disorder.

Harm reduction services

Most countries quickly adapted to the unprecedented conditions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic by moving to telemedicine-based delivery of services. During the pandemic, most countries also lowered the threshold for opioid agonist treatment (OAT) initiation and increased the duration of OAT (such as methadone and buprenorphine) dispensed. Home-based delivery of OAT was initiated by countries such as Australia, Norway and Scotland (UK).

In the USA, a major change during the pandemic was amendment of regulations to exempt physicians from certain certification requirements (commonly known as X-waiver) needed to prescribe buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder. Further, buprenorphine can be initiated via telehealth, but methadone maintenance treatment still needs to be started in person. During the pandemic, the USA piloted managed alcohol programmes (MAPs) among homeless individuals with severe alcohol use disorder to aid adherence to COVID-19 protocols. This study provided a foundation for expansion of MAPs as a recognised public health intervention for those unable to stabilise within existing care systems.Reference Ristau, Mehtani, Gomez, Nance, Keller and Surlyn9

During the pandemic, Australia increased roll-out and uptake of long-term injectable buprenorphine as a means of increasing access and convenience and decreasing travel-related risks. In Norway, harm reduction measures were strengthened by increasing access to clean syringes and equipment and lowering the threshold for OAT. Some countries increased the availability of needles from vending machines, increased provision of take-home naloxone, and increased funding and support for naloxone provision. At a national level, many countries, such as India, the UK, Australia and Norway, formulated guidance documents that included management guidelines, information and education materials related to SUDs.Reference Scheibein, Stowe, Arya, Morgan, Shirasaka and Grandinetti10 In Indonesia, anti-retroviral drugs for people with SUDs were delivered to their residences. In Indonesia, addiction specialists were deployed for COVID-19 care, resulting in considerably fewer healthcare professionals available to service patients with SUDs. With the prolongation of the COVID-19 pandemic and advent of further waves, harm reduction services continued to be significantly affected.

Abstinence-based services

In many countries SUD treatment centres, including rehabilitation centres and those linked to general hospitals, were closed as they were considered non-essential.Reference Kouimtsidis, Pauly, Parkes, Stockwell and Baldacchino2 In Australia, because of social distancing regulations and requirements, there was reduction in overall bed numbers and an increased waiting list to get into treatment. In Indonesia, financial problems during the COVID-19 pandemic also led to lack of medication adherence because it was difficult for some patients to reach the new treatment centres. Integration of patients’ data as a unified system is still limited in Indonesia, so the new treatment centres had to reassess the patient, disrupting continuity of care. Reintegration of patients from rehabilitation services into the community also became problematic because the involvement of family and the community during the in-patient treatment or rehabilitation was limited.

The EMCDDA reported a disruption to therapeutic communities and to those in aftercare settings as unemployment increased during the lockdown.8 Scotland (UK) and Greece made legislative changes to provide shelter for homeless people, one of the most vulnerable populations with SUDs.

Although in many countries, alcohol was included as part of ‘essential’ goods and supply was maintained throughout the pandemic, in other countries, such as India and South Africa, the sale of alcohol was banned during the COVID-19 lockdown.Reference Neufeld, Lachenmeier, Ferreira-Borges and Rehm11 In India, such a forced abstinence resulted in complicated withdrawals among people with alcohol use disorder (the forced abstinence model) but access to treatment for alcohol-related emergencies was not possible because of the lockdown.Reference Narasimha, Shukla, Mukherjee, Menon, Huddar and Panda12 Vulnerable populations, especially those at risk of homelessness and those of lower socioeconomic status, went into unwanted abstinence due to disruption of services. In some countries, patients on OAT and benzodiazepine prescriptions who needed to be admitted to COVID-19 isolation facilities but were unable to access SUD services owing to the risk of contagion were advised on self-tapering regimens to avoid severe withdrawals. Owing to lack of availability of harm reduction services in isolation facilities and hospitals, many feared forced abstinence if they tested positive for COVID-19 and therefore some avoided testing. These unprecedented public health measures had an impact on social care systems, limiting the essential services to individuals with severe SUDs and, in some cases, widening extreme social inequities such as poverty and homelessness.Reference Kouimtsidis, Pauly, Parkes, Stockwell and Baldacchino2

Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected people with SUDs because of lockdowns, sudden policy changes and disruption of treatment services. However, countries adapted quickly in provision of harm reduction services by initiating tele-health services, home-based delivery of medication, lowering the threshold for OAT initiation and relaxing the prescribing norms for opioid substitution medication, increased roll-out of long-term injectable buprenorphine and increased access to clean syringes. In several countries, guidance documents for healthcare professionals on the management of SUDs during the pandemic and adequate information for the general population have been made available in the public domain. Some people with SUDs went into unwanted abstinence due to policy changes and disruption of services. With the prolongation of the pandemic and subsequent waves, substance use treatment services continue to be affected drastically. Finally, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic along with ongoing SUD epidemic synergistically resulted in a syndemic across the world. Therefore, it is important to identify and develop country- or region-specific strategies to mitigate the effect of the ongoing pandemic on people with SUDs. Global awareness is crucial for responsible managing of SUDs during the pandemic, and the development of international health policy guidelines is an urgent need in this area.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

V.L.N., R.B., A.B. and S.A. conceived the idea for the study and presentation of country profiles. V.L.N. wrote the first draft. J.B., E.H., M.F., F.C., R.B., C.K., A.B. and S.A. contributed to the country profiles and revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the presented information and contributed to the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

M.F. is an employee of the US Federal Government and is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) intramural funding (ZIA-DA000635 and ZIA-AA000218), outside of this research. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or any other agencies.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.