Introduction

Suicide is the third leading cause of death among youths worldwide (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zheng, Li, Xiong, Yu, Shi and Hu2020). Suicidal behaviours, including suicidal ideation (thought of killing oneself) and suicidal attempt (non-fatal, self-inflicted destructive acts with explicit or inferred intent to die), are well recognised precursors of suicide death. In fact, evidence suggests that over one-third of youths with suicidal ideation go on to attempt suicide, and suicide rates consistently increase from childhood to adolescence (Cha et al., Reference Cha, Franz, Guzmán, Glenn, Kleiman and Nock2018). A greater understanding of the risks associated with suicidal behaviours is needed in order to guide more effective intervention and prevention strategies in context-specific ways (Dervic et al., Reference Dervic, Gould, Lenz, Kleinman, Akkaya-Kalayci, Velting, Sonneck and Friedrich2006; Yip et al., Reference Yip, Yousuf, Chan, Yung and Wu2015). Identifying these risk factors in this particular age group across different societies is therefore of pressing importance. However, existing studies have been largely limited by the use of relatively small sample sizes and by the evaluation of cohorts mostly collected in a single, high-income country (HIC) (Yip et al., Reference Yip, Yousuf, Chan, Yung and Wu2015).

Family characteristics, along with individual and societal factors, have been shown to contribute to youth suicidal behaviours, and among these, family socioeconomic disadvantage has been suggested to be one of the major risk factors (Aggarwal et al., Reference Aggarwal, Patton, Reavley, Sreenivasan and Berk2017). Family socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with a wide array of exposures, resources and susceptibilities that may impact health (Galobardes et al., Reference Galobardes, Shaw, Lawlor, Lynch and Smith2006), and families with lower SES suffer from multiple forms of disadvantage (Reiss et al., Reference Reiss, Meyrose, Otto, Lampert, Klasen and Ravens-Sieberer2019). Through material hardship, greater parental stress and parental mental health problems and harsher parenting, familial socioeconomic inequalities can contribute to poor mental outcomes on the offspring (Weinberg et al., Reference Weinberg, Stevens, Duinhof and Finkenauer2019).

Parental education, as one of the most commonly assessed indicators of familial SES, has been widely studied for its relation to youth mental health outcomes, and found to play a role even when other socioeconomic confounders are taken into account (Sonego et al., Reference Sonego, Llácer, Galán and Simón2013). Furthermore, parental education has been found to have a stronger relationship with child and adolescent mental health compared to other family SES indicators, such as parental unemployment or lower occupational status (Reiss et al., Reference Reiss, Meyrose, Otto, Lampert, Klasen and Ravens-Sieberer2019). Parental education, specifically reflecting the possession or availability of knowledge, has been noted to affect parenting styles (Carr and Pike, Reference Carr and Pike2012), disciplinary practices (Bøe et al., Reference Bøe, Sivertsen, Heiervang, Goodman, Lundervold and Hysing2014), health investment (Lindeboom et al., Reference Lindeboom, Llena-Nozal and van Der Klaauw2009), home literacy environment (Keshavarz and Baharudin, Reference Keshavarz and Baharudin2013) and parental school involvement (Padilla-Moledo et al., Reference Padilla-Moledo, Ruiz and Castro-Piñero2016), which have been proposed to independently and/or jointly influence youth mental health outcomes.

When it comes to youth suicidality, there is yet no agreement as to whether and how parental education could be associated with a higher risk. While some studies have reported lower parental education to be a risk factor for youth suicidal behaviours (Dubow et al., Reference Dubow, Kausch, Blum, Reed and Bush1989; Andrews and Lewinsohn, Reference Andrews and Lewinsohn1992; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Hawton and Rodham2004), others have found no association or even a protective role (Gage, Reference Gage2013; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Yan, Tang, Huang, Ma, Ye and Yu2017). Differences in sociocultural contexts in these studies have been proposed to be contributing to these contradictory findings (Bøe et al., Reference Bøe, Øverland, Lundervold and Hysing2012). As a result, an effort should be made to further elucidate the role of sociocultural contextual differences in these studies, as this could not only help the interpretation of results, but also highlight potential different mediating pathways through which parental education could be related to the risk of youth suicidal behaviours across the globe. Therefore, we conducted this first systematic review and synthesis of empirical evidence on parental education and youth suicidal behaviours, while taking into account the possible role of sociocultural contexts, as reflected by geographical region and country income level.

The primary goal of this systematic review was to establish whether there is an association between parental education and either youth suicidal ideation or suicidal attempts (including suicide death). Our secondary goal was to determine if geographical region and country income level could potentially moderate any observed association.

Methods

Search strategy

We followed the Meta-analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines (Stroup et al., Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson, Rennie, Moher, Becker, Sipe and Thacker2000). We conducted a systematic search on PubMed, PsycINFO, Medline and Embase to screen for studies reporting on the association between parental education and youth suicidality. We applied the following search string: (family OR familial OR household OR parental OR caregiver OR guardian OR mother OR maternal OR father OR paternal) AND (education* OR school*) AND (suicid* OR parasuici* OR ‘self-harm’ OR ‘self-injur*’ OR ‘self-poison*’ OR ‘self-cut*’ OR ‘self-destruct*’ OR ‘self-inflict*’) AND (teen OR teenager OR adolescen* OR children OR youngster OR youth). We limited search results to (1) English publications, (2) peer-reviewed journals and (3) published between January 1900 and December 2020. Two authors (P. J. C. and N. M.) independently assessed the eligibility of each study. When eligibility could not be established through titles and abstracts, the authors retrieved the full text. Any discrepancy was resolved through discussion and opinion of a third author (P. D.). The search strategy initially yielded a total of 6091 articles (after de-duplication). The search was later supplemented by a screening of the references of the studies included.

Inclusion criteria

We included papers that fulfilled the following criteria: (1) education of parents (or parental figures, such as caregivers or household heads) was assessed and reported as a categorical variable, or reported with beta coefficients if education was measured as a continuous variable; (2) youth suicidal behaviour (thoughts/ideations, attempts or deaths) was assessed separately and independently from other constructs (i.e. other risky behaviours or mental disorders) before the age of 18 (included); (3) concrete case number or person-years data in accordance with different parental educational level was provided, or quantitative associations between parental education level and adolescent suicidal behaviour was reported in the forms of odds ratio (OR) or beta coefficients. We excluded studies of youths with autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia spectrum disorders and intellectual disabilities. For studies that investigated the same population, we chose the larger or, where this was equal, the most recent one. Reviews, meta-analysis, commentaries, editorials and correspondences were not included.

Study factor

Parental education level, the main study factor, was assessed and reported differently across studies. For the primary analyses, we coded studies according to their treatment of parental education level as a predictor of outcome. For the secondary analyses, we re-categorised parental educational levels into low, middle and high for the purpose of standardisation. Using the International Standard Classification of Education level 3 (ISCED 3; http://uis.unesco.org) as the cut-off point, we categorised an education level below ISCED 3 as low education (i.e. illiteracy, no education, basic or primary education, middle school, lower secondary education or education years below 12); an education level equals to ISCED 3 as middle education (i.e. upper secondary education, high school graduate or education years equal to 12) and an education level above ISCED 3 as high education (i.e. college/university/master/doctoral degree or education years above 12).

Outcomes

Outcomes of interest were youth suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts (including suicide death). We used the definitions or criteria made to determine positive outcomes in each study. However, studies on youth self-harming behaviours that did not specify whether this had a suicidal intent were excluded from the present review.

Data extraction

General study characteristics including name of the first author, publication year, country/region where the study was conducted, cohort name, case definition and outcome type were extracted. We also extracted: (1) classifications of parental education; (2) methods of assessment of parental education and youth suicidal behaviour (questionnaire, interview or data-linkage); (3) source of information about suicidal behaviours (adult-report, children-report or data-linkage); (4) timeframe of suicidal behaviour assessment (lifetime or specific timeframe, such as e.g. previous 6–12 months); (5) type of data from which the association was determined (cross-sectional or longitudinal); (6) sample type (community or clinical); (7) female/male participant ratio; (8) study country income level as per The World Bank 2021 data (high or low and middle; https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org) and (9) study geographical region based on the sustainable development goal indicators, the regional groupings defined under the Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistical Use of the United Nations Statistics Division (sub-Saharan Africa, Northern Africa and Western Asia, Central and Southern Asia, Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Oceania, Europe and Northern America; https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/regional-groups). For pooling, we obtained the maximally adjusted estimate of the OR compared with the reference for each education level, and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). If ORs were unavailable, we computed ORs from raw data presented in the original studies. If the study measured parental education in years and reported only beta coefficients, we multiplied the coefficients by 4 (a correction factor chosen to reflect the difference in mean years of education between high- and low-parental education level) to better align the results with the rest of the studies on the same scale. If both maternal and paternal education levels were provided, maternal education level was chosen as representative, as more studies chose maternal education as a proxy for parental education. If the study provided survey year or sex stratification of the youths, the results were analysed separately.

Risk of bias assessment

We used the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for (1) cross-sectional studies, (2) cohort studies and (3) case control studies to assess risk of bias. Information on (1) sample selection, (2) comparability of cohorts and (3) assessment of outcome were collected. For cohort studies, however, we did not include the question about whether follow-up duration was sufficiently long for the outcome to occur, as this was not applicable. As a result, a maximum score of 8, 8 and 9 could be reached for cross-sectional studies, cohort studies and case control studies, respectively. A total score of 0–4 was considered as indicative of high risk of bias; 5–6 of some concern and 7–9 of low risk of bias.

Data analysis

Random effects meta-analyses with DerSimonian–Laird estimator (DerSimonian and Laird, Reference DerSimonian and Laird1986) were conducted using R (version 4.0.3 GUI 1.73) with the metaphor (Viechtbauer, Reference Viechtbauer2010) and meta (Balduzzi et al., Reference Balduzzi, Rücker and Schwarzer2019) packages to estimate pooled ORs and 95% CI. Suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt/death were treated as separate outcomes and analysed independently. For the primary analysis, we first derived pooled estimates of the association with outcomes of the lowest parental education level against the highest parental education level from each study with the highest level as the reference; if the study treated parental education as a continuous variable or only provided regression coefficients, we used the beta coefficients (corrected as aforementioned if education was measured in years) as the log odds (Szumilas, Reference Szumilas2010). We then performed secondary analyses by pooling estimates of the middle parental education level group (equal to ISCED 3) against the high group (above ISCED 3) with the high group as the reference, the low group (below ISCED 3) against the middle group with the middle group as the reference, and the low group against the high group with the high group as the reference. Secondary analyses were designed to reveal more details on whether and how a specific parental educational achievement could be associated with youth suicidal behaviours.

Heterogeneity was assessed by Q test and I 2 statistics. An I 2 value of 50% was indicative of moderate heterogeneity, whereas 75% was considered substantial. When heterogeneity was observed in the data, we tested moderating effects by applying mixed-effects models. Geographical region and country income level were selected as moderators of interest. Other potential moderators investigated were sample type, female ratio, study design, outcome assessment methods, outcome assessment subject, timeframe of the assessed outcome and risk of bias. Risk of publication bias was assessed via visual inspection of funnel plots, supplemented by Egger's test (Egger et al., Reference Egger, Smith, Schneider and Minder1997).

Results

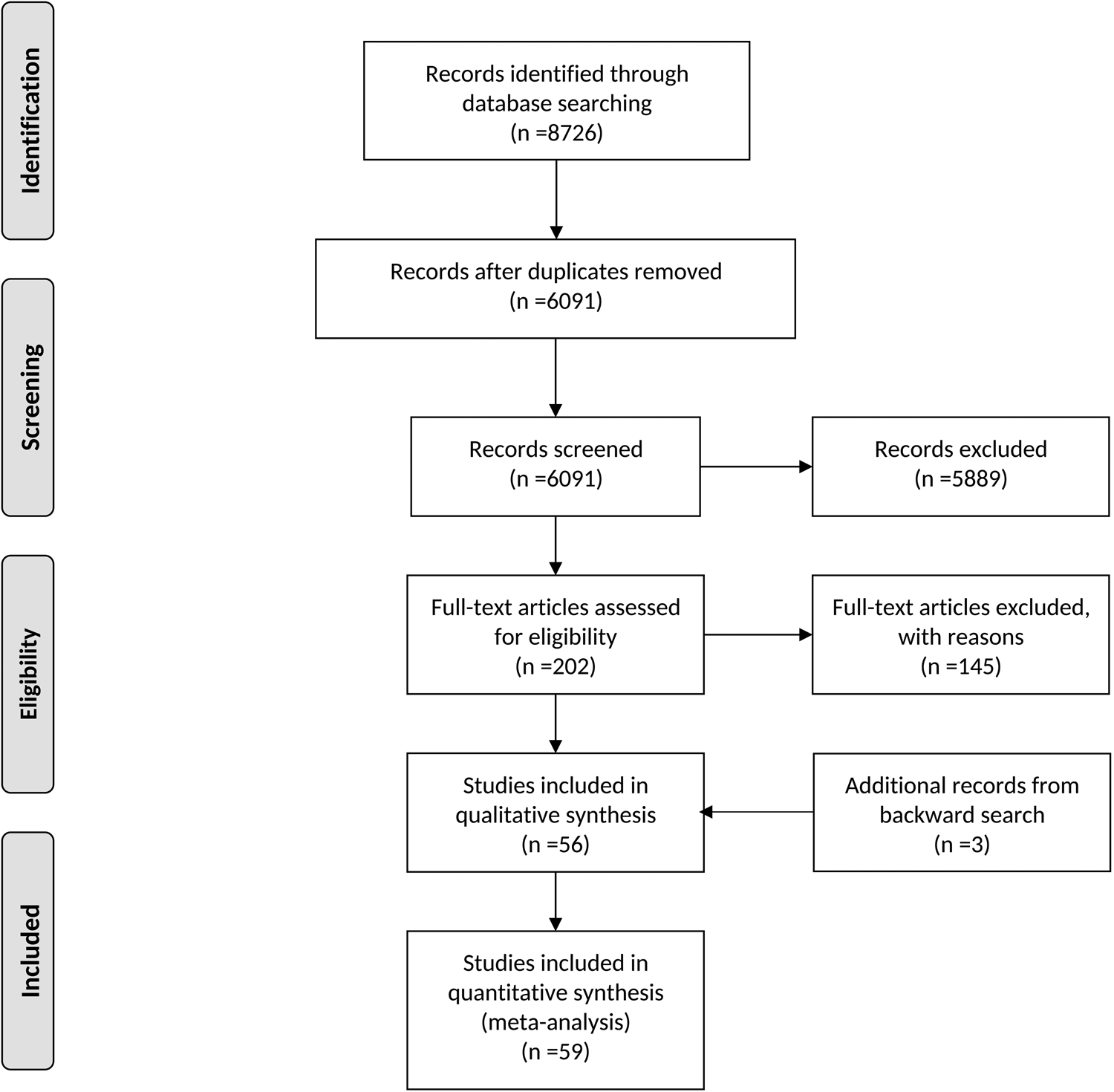

We identified 8726 articles from PsycINFO, Medline, Embase and PubMed. Of these, 2635 were duplicates and were therefore removed, with 6091 remaining. Further 5889 were later excluded based on titles and abstracts. An additional 145 studies were excluded following screening of full texts. Backward search of the references of the remaining 56 articles resulted in three additional records, leaving a total of 59 articles satisfying the eligibility criteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Flow diagram of the present systematic review and meta-analysis.

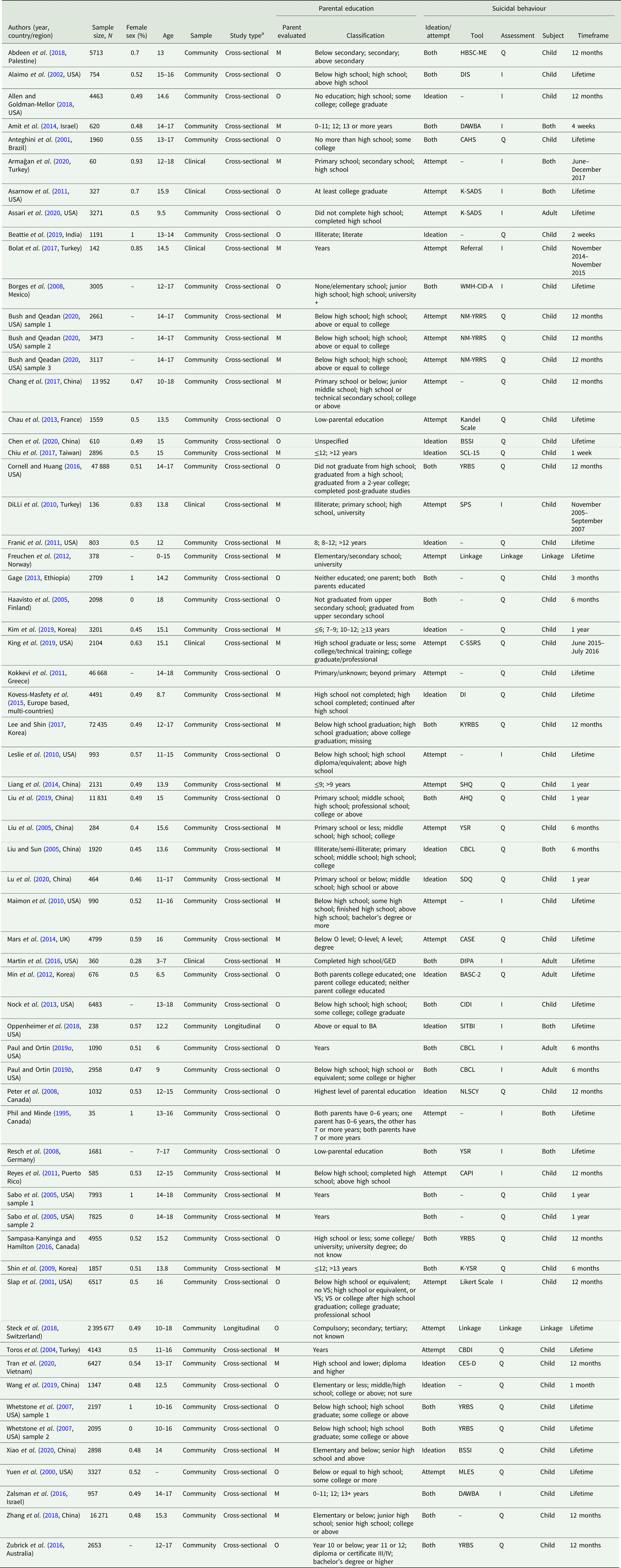

The 59 articles, published between 1900 and 2020, encompassed 63 eligible study samples, with samples ranging 35 to 2 395 677 individuals, with a total sample size of n = 2 738 374. Details of the samples included are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis

AHQ, Adolescent Health Questionnaire; BASC-2, Behaviour Assessment System for Children; BSSI, Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation; CAHS, Canada Adolescent Health Survey; CAPI, Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing; C-SSRS, Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale; CASE, Child and Adolescent Self-harm in Europe; CBCL, Child Behaviour Checklist; CBDI, Child Beck Depression Inventory; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DAWBA, Development And Well-Being Assessment; DI, Dominic Interactive; DIPA, the Diagnostic Infant and Preschool Assessment; DIS, Diagnostic Interview Schedule; HBSC-ME, Health Behaviour in School aged Children in the Middle East study; I, Interview, K-SADS, Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; KYRBS, Korean Youth Risk Behaviour Survey; K-YSR, Youth Self Report-Korean version; M, Mother; MLES, Major Life Events Scale; NLSCY, National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth; NM-YRRS, New Mexico Youth Risk and Resiliency Survey; O, Other; Q, Questionnaire, SCL-15, Symptom Checklist-15 item version; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; SHQ, Self-Harm Questionnaire; SITBI, Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviours Interview; SPS, Suicide Probability Scale; WMH-CIDI-A, World Mental Health computer assisted Adolescent version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview; YRBS, Youth Risk Behaviour Survey; YSR, Youth Self Report.

a ‘Cross-sectional’ type refers to the outcome data used to determine the association in the study was assessed at a single timepoint; ‘longitudinal’ type refers to the outcome data used to determine the association in the study was repeatedly assessed and accumulated during the follow-up period.

The samples were mainly from the community (k = 57), with only six studies including clinical populations. Overall, 61 samples estimated the association between parental education and youth suicidal behaviour using outcome data measured at a single time point (cross-sectional), and two samples used cumulative outcome data from repeated assessments obtained during a follow-up period (longitudinal). Most of the samples were from Europe and Northern America (k = 34), followed by Eastern and South-Eastern Asia (k = 16), Western Asia (k = 7), Latin America and the Caribbean (k = 3), Central and Southern Asia (k = 1), Oceania (k = 1) and sub-Saharan Africa (k = 1). A minimal sample number of six from a particular geographical region would qualify its inclusion in the moderator analysis. Most samples included school age adolescents (k = 56) and only seven samples included children under the age of 10 years. Half of the samples used maternal education as their study factor (k = 32), while the others assessed education of fathers, caregivers, wage earners or the highest education in the household or between parents. In total, 47 samples incorporated ISCED 3 or equivalent in their classification of parental education, therefore allowing us to perform secondary comparisons as detailed in ‘Methods’ section. Among the 63 samples included, 39 investigated suicidal thought/ideation as one of their primary outcomes, and 46 investigated suicidal attempt/death, 21 studied both. Most samples assessed these outcomes through questionnaires (k = 40), and the majority derived information regarding suicidal behaviours directly from the participants (k = 49). Among the samples included, 34 originally reported adjusted ORs, ORs or beta coefficients, while 29 reported cross-tabulated data. The results of the risk of bias assessment are presented in the online Supplementary material (Tables S1–S3). Among the 39 samples that reported an association between parental education and suicidal ideation, 62% (k = 24) fell into the high-risk category, 36% (k = 14) were rated as of some concerns and only 2% (k = 1) were rated as low risk. On the other hand, of the 46 samples that evaluated suicidal attempt, 59% were rated as low or of some concern (k = 6 and 21), while 41% (k = 19) were rated as high risk.

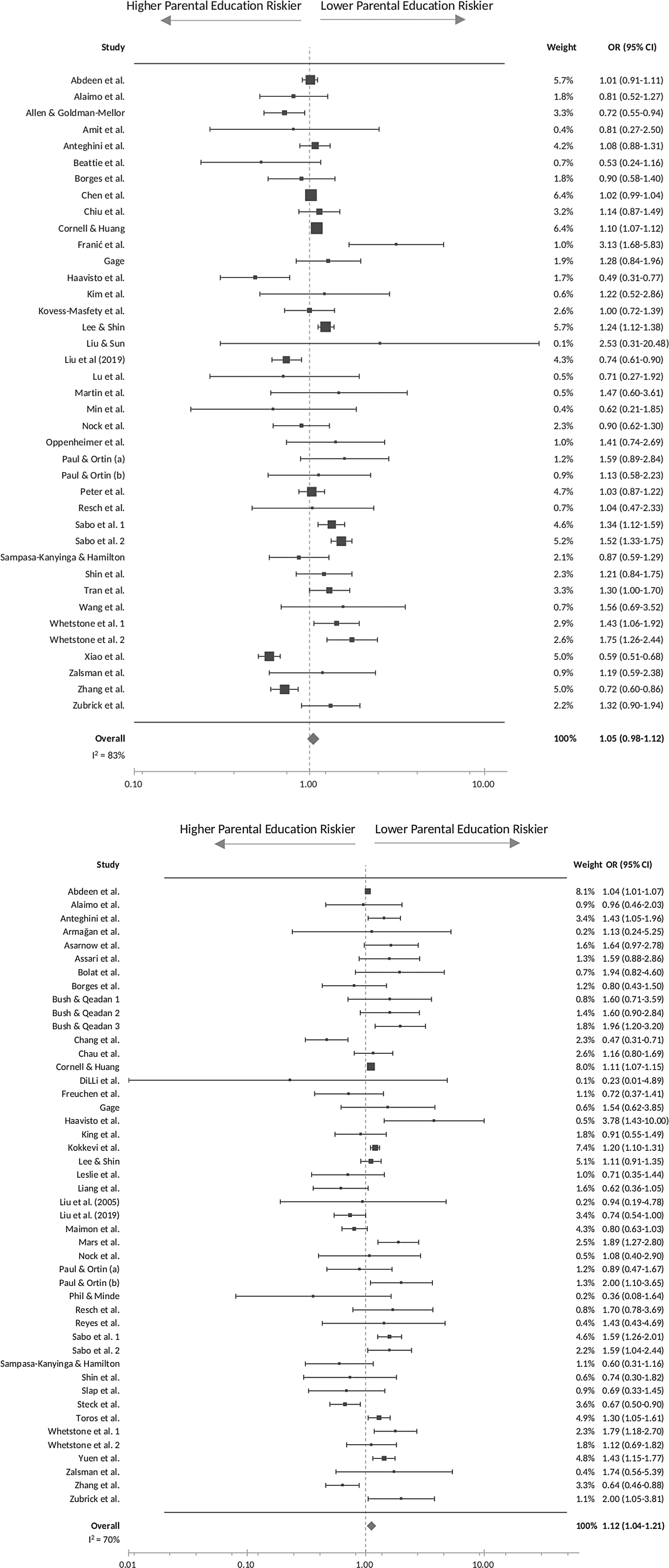

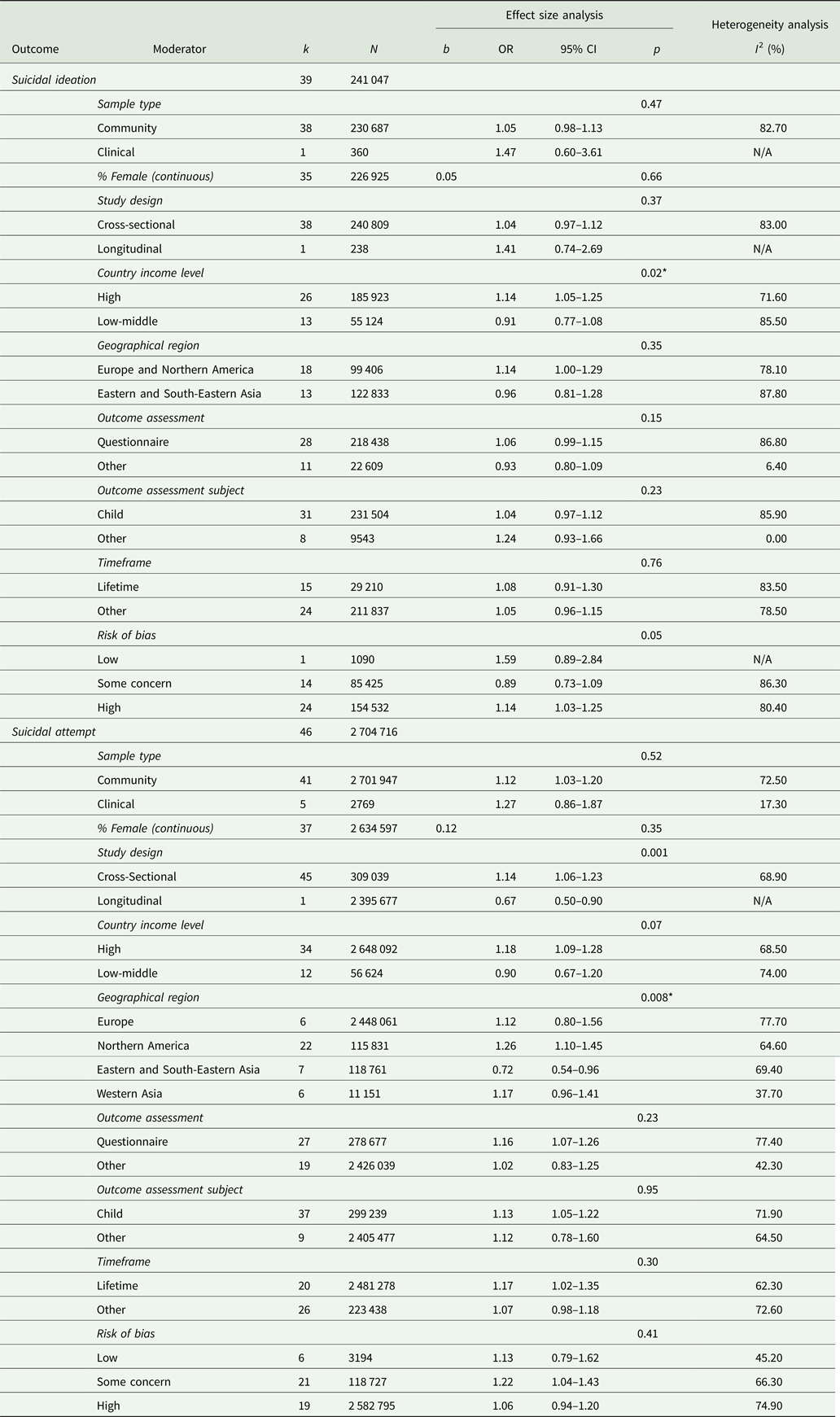

For the purpose of evaluating the overall effect of parental educational on youth suicidal behaviours, in the primary meta-analyses we used ORs of the lowest parental education level defined in each study with the highest parental educational level as the reference wherever possible, to estimate effect sizes. Pooled effect sizes indicate the risk or likelihood for youth suicidal behaviours for youths with the lower educated parents. Figures 2a and 2b summarise the pooled ORs for suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt. The pooled results reveal a small, but positive association between lower parental education and youth suicidal attempts (OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.04–1.21), but not suicidal ideation (OR = 1.05, 95% CI = 0.98–1.12). The heterogeneity ranged from moderate (I 2 = 70% for suicidal attempt) to substantial (I 2 = 83% for suicidal ideation), indicating the need for moderator analyses (Table 2). These showed that geographical region (p = 0.008) and country income level (p = 0.02) were significant moderators of the direction and strength of the association between lower parental education and youth suicidal attempts and ideation. In particular, lower parental education was associated with an increased risk of youth suicidal attempts for studies conducted in Northern America (OR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.10–1.45), but such association was reversed in studies conducted in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, where higher parental education was associated with an increased risk of youth suicide attempts (OR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.54–0.96). In addition, lower parental education was only associated with an increased risk of youth suicidal ideation in HICs (OR = 1.14, 95% = 1.05–1.25), and the association was absent in studies conducted in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (OR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.77–1.08). Egger's regression test indicated no significant publication bias for both outcomes. The funnel plots also showed no notable asymmetries (online Supplementary Figs S1A and S1B).

Fig. 2. (a) Primary analysis: forest plot of the association between parental education and youth suicidal ideation. (b) Primary analysis: forest plot of the association between parental education and youth suicidal attempts.

Table 2. Univariate moderator analysis of the relationship between parental education and youth suicidal behaviours

*p < 0.05.

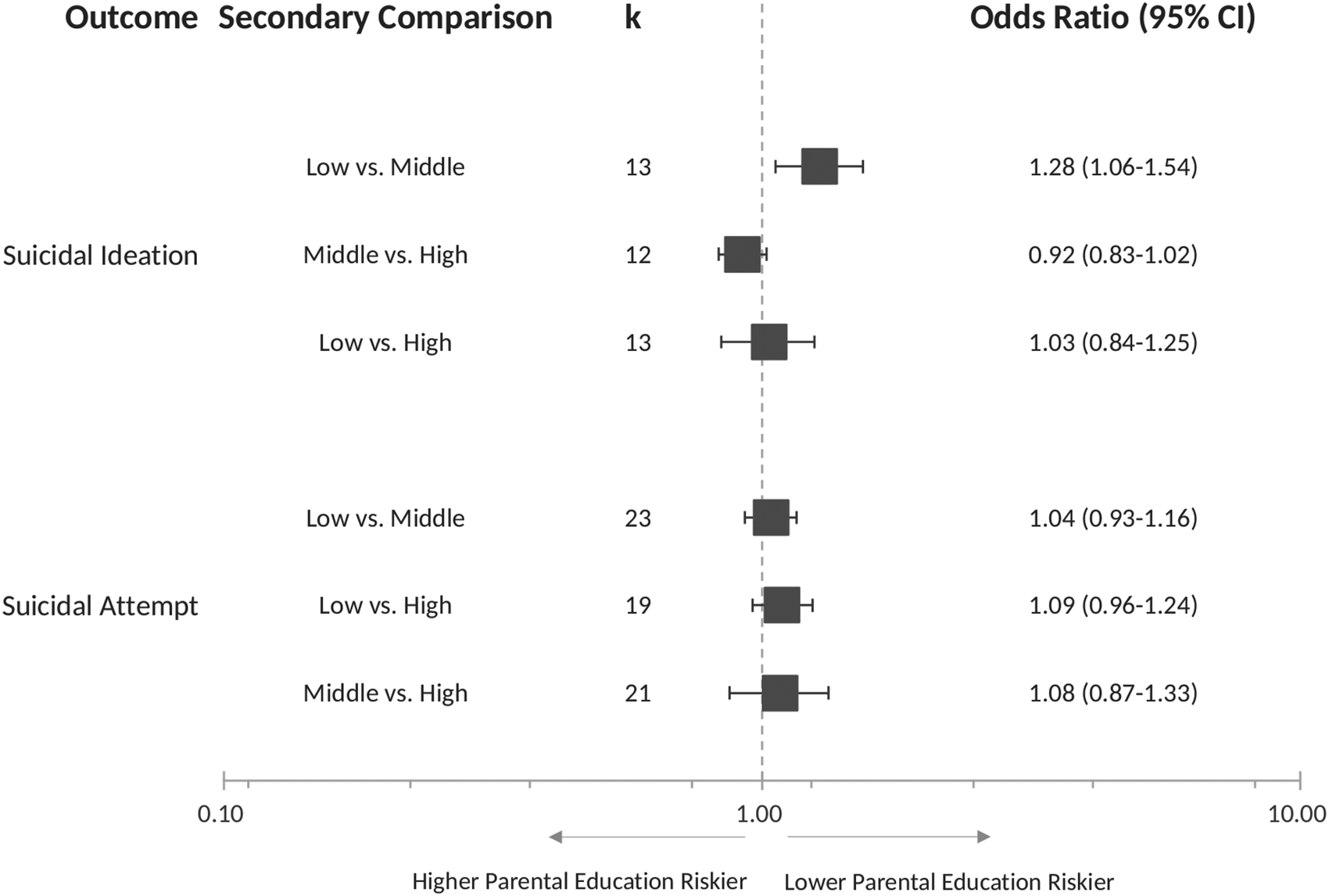

A total of 47 samples incorporated ISCED 3 or equivalent in their classification of parental education. These studies were selected for the secondary analyses, in which we evaluated the relationship between lower parental education and youth suicidal behaviours across three parental education level subgroups (low, middle and high). Pooled results showed an increase in risk for suicidal ideation in youths of parents with low education level compared to those of parents with middle-educational level (k = 13, OR = 1.28, 95% CI = 1.06–1.54) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Secondary analysis: forest plot of the associations between lower parental education and youth suicidal behaviours across parental education level subgroups.

Discussion

Our main finding is that lower parental education is significantly associated with a small increase in the risk of youth suicidal attempts. Furthermore, we found that having parents with a low education level (below ISCED 3) is associated with a higher risk of suicidal ideation than having parents with a middle-education level (equals to ISCED 3). Finally, we also found that the association between parental education and youth suicidal behaviours is moderated by both geographic region and country income level. Specifically, lower parental education is associated with an increased risk of youth suicidal ideation and attempts in studies conducted in HICs and Northern America, respectively, while the opposite is true for studies conducted in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, where higher parental education appears to be associated with a higher risk of youth suicidal attempts.

Our first finding is consistent with reports from an older systematic review conducted by Evans et al. (Reference Evans, Hawton and Rodham2004), which reported that among family socioeconomic characteristics, lower parental educational level and worries for family finance were the only factors associated with an increased risk of adolescent suicidality. Multiple potential pathways have been proposed to mediate the association between higher parental education level and more favourable youth health outcomes. For instance, several studies conducted in the West support that higher parental education is associated with better parent–child interaction (Zayas et al., Reference Zayas, Kaplan, Turner, Romano and Gonzalez-Ramos2000), more positive parenting (Carr and Pike, Reference Carr and Pike2012), healthier lifestyle (Jablonska et al., Reference Jablonska, Lindblad, Östberg, Lindberg, Rasmussen and Hjern2012) and increased resource buffering against stressful life events and supporting children's problem solving (Reiss et al., Reference Reiss, Meyrose, Otto, Lampert, Klasen and Ravens-Sieberer2019). Higher parental education could also be indicative of a broad social and economic positive influence on the home environment, as higher education could give access to higher earnings and more affluent living (Lindeboom et al., Reference Lindeboom, Llena-Nozal and van Der Klaauw2009). Higher education could also enable parents to better recognise problematic issues in adolescents via stronger mental health literacy and access to sources of support (Villatoro et al., Reference Villatoro, DuPont-Reyes, Phelan, Painter and Link2018). All of the above could potentially help promote child and adolescents' well-being and better mental health. In line with this, our first finding supports a possible protective role of higher parental education against youth suicidal attempts.

In contrast, we found no association between lower parental education and youth suicidal ideation in the primary analysis, although such an association became evident in a secondary analysis across education level subgroups, where low education levels were associated with an increased risk of suicidal ideation compared to middle-education levels. The fact that lower parental education was associated with an increased risk of youth suicidal attempts but not with a risk of suicidal ideation in our primary analysis somewhat echoes an observation previously made by Kapi et al. (Reference Kapi, Veltsista, Kavadias, Lekea and Bakoula2007), who suggested that family SES could be more closely related to externalising behaviours rather than internalising domains of adolescent psychopathology. Also, 90% of participants included in studies of suicidal ideation were in their middle to late adolescence, and some authors have suggested that the influence of family SES on youth mental health outcomes could diminish with age (Bøe et al., Reference Bøe, Øverland, Lundervold and Hysing2012).

Taken together, the findings of our primary and secondary analyses suggest that the relationship between parental education and youth suicidal ideation might not be linear. Different parental educational milestones may have different effects on this particular outcome, as our secondary analyses showed youths with parents who completed high school had a relatively lower risk of disclosing suicidal ideation compared to those whose parents did not acquire a high school diploma. In contrast, parental education higher than high school was no longer associated with such reduced risk, suggesting that other factors might counteract a potential protective effect of education.

The relevance of factors other than parental education alone is supported by our finding that geographical region and country income level moderated the relationship between parental education and youth suicidal behaviours. This finding suggests that cultural, psychosocial, economical contexts and possibly biological factors, could play a significant role in this particular association. Previous evidence has suggested that contextual differences could affect the relationship between parental education and youth's well-being (Assari et al., Reference Assari, Caldwell and Mincy2018). When studying the influence of parental education, it is vital to take into account contextual factors such as politics, racial compositions, societal attitudes, neighbourhood characteristics, in which families are embedded, as the effect of socioeconomic indicators is complex and can vary across different contexts (Assari et al., Reference Assari, Caldwell and Mincy2018). For instance, while high-parental education may be linked to positive and less harsh parenting styles in Western cultures, it has also been associated with higher academic expectations and performance stress in Asian cultures, particularly Chinese (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Yan, Tang, Huang, Ma, Ye and Yu2017). Meanwhile, social expectations and academic pressure to excel are risk factors shared among youths in Asian countries, and prior research has already highlighted that differences in patterns of suicide between East Asia and the West merit further attention (Kwak and Ickovics, Reference Kwak and Ickovics2019).

Similarly, previous literature has also indicated that cultural and social differences between LMICs and HICs could play a role in the presentation and course of youth self-injurious behaviours (Aggarwal et al., Reference Aggarwal, Patton, Reavley, Sreenivasan and Berk2017). The role of parental education in child health outcomes has become more attenuated over recent decades in low-resource settings as reported by a recent study (Karlsson et al., Reference Karlsson, De Neve and Subramanian2019). Our findings are especially important in light of the fact that 78% of all self-imposed lethal acts occur in LMICs, while the vast majority of research concerning youth suicide is based on populations living in North America and in European countries (Kim, Reference Kim2019). Our results highlight the importance of investigating context-specific risk and protective factors for youth suicidality, as data informing country and regional variation are urgently warranted to identify modifiable risk factors and to inform differential service needs globally (Biswas et al., Reference Biswas, Scott, Munir, Renzaho, Rawal, Baxter and Mamun2020).

Nevertheless, our findings should be interpreted with caution in view of some important limitations. For example, moderate to substantial heterogeneity was present in the studies included in the primary analyses. Despite our extensive efforts to explore the sources, we could identify only some of the many possible moderators. Residual differences between studies could be related to sample characteristics, study design, and definitions and classifications of parental education. In addition, the qualitative assessment revealed that several studies had medium to high risk of bias. This was mainly due to suboptimal practices in exposure ascertainment and outcome assessment, since most studies applied self-administered questionnaires to participants. Also, the cross-sectional nature of most of the data included did not make it possible to conclude whether and how parental education is directly or indirectly associated with youth suicidal behaviours. Finally, the studies included in the meta-analysis varied widely in sample size, with one single study contributing to over 85% of the total participant numbers (Steck et al., Reference Steck, Egger, Schimmelmann and Kupferschmid2018). However, this study was not overly represented in the synthesis results as it investigated youth suicide death rather than suicidal ideation or attempts. With a much lower prevalence rate, the precision of the study's estimated effect size was reduced despite having a large sample size, which attenuated the study's weight in the random effects model.

On the other hand, the present study also has several strengths. First, we believe that this is the first study to have systematically assessed the effect of parental education as an independent variable in youth suicidal behaviours. As noted in previous research, different indicators of family SES could affect health outcomes through different pathways, and therefore should not be combined (Padilla-Moledo et al., Reference Padilla-Moledo, Ruiz and Castro-Piñero2016). Second, by considering suicidal ideation and attempts separately, we show that these two components of suicidal behaviours, although highly correlated, could in fact have different risk profiles and require different preventive and intervention strategies. Third, our secondary analyses suggest that any effect may not follow a ‘dose-dependent’ pattern. Fourth and last, our results show how critical it is to acknowledge the between-context variation in the association between parental education and youth mental health outcomes.

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis offers a comprehensive synthesis of existing evidence on the relationship between parental education and youth suicidal behaviours, notwithstanding the high heterogeneity of the studies included. In general, our findings provide initial evidence of an association between lower parental education and increased risk of youth suicidal attempt. In addition, the findings suggest that this association may differ across different geographical and economical contexts, possibly related to cultural, psychosocial and/or biological factors. This indicates that it is crucial for future research to gather more evidence on the determinants of youth suicidal behaviours across the global setting. Furthermore, it highlights the importance of taking into account the cultural as well as the familial context in the clinical management of youth suicidal behaviour in our increasingly multicultural societies.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S204579602200004X.

Data

All data used in the systematic review and meta-analyses can be found in the included studies. Extracted data by the authors can be found in the online Supplementary materials.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Abroad Advanced Study Fellowship, Chang Gung Medical Foundation, Taiwan (P. J. C.) and the Medical Research Council, UK (P. D., grant number: MR/S003444/1). The funders had no influence on the design, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing, reporting or submitting the study for publication.

Author contributions

P. J. C. and N. M. reviewed literature search results independently. P. J. C. and N. M. had full access to the data and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity. P. J. C., N. M., C. S., A. J. L., C. M., S. H., C. N. and P. D. completed concept formation and study design. P. J. C., N. M., C. S., A. J. L., C. N. and P. D. contributed to data selection, data analysis or interpretation of the data. P. J. C. drafted the manuscript. N. M., C. S., A. J. L., X. M., R. P., M. M., C. M., S. H., G. S., C. P., M. A. M., G. M., C. N. and P. D. critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. P. J. C., N. M., C. S., A. J. L., C. N. and P. D. contributed to the statistical analysis. P. D. provided administrative, technical or material support. N. M., A. J. L., C. N. and P. D. provided expert supervision during data extraction, analysis and interpretation and writing of the manuscript. C. S., C. P. and M. A. M. provided expert supervision during data interpretation and writing of the manuscript. Senior academic P. D. supervised all stages of elaboration of the study.

Role of the funding source

The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

Conflict of interest

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.