EDITORS’ NOTE: This article is based on the Government and Opposition/Leonard Schapiro Lecture given by Mark Blyth in Glasgow on 10 April 2017. That lecture was entitled: ‘What if Brexit, Trump and Grexit Are Noise Rather than Signal? Exploring the Politics of a Secularly Stagnant World.’

Normally the editors of Government and Opposition ask scholars who give a Schapiro Lecture to write up their talks for publication in the journal. In this case, however, Blyth wanted to do something more ambitious and use his lecture as a starting point for engagement with an important research agenda on the relationship between economic policymaking and political transformation in advanced industrial societies. Blyth knew that Jonathan Hopkin was actively working in that area, but from a different perspective. He invited Hopkin to build on the lecture as a collaborative enterprise with the expectation that the whole of their joint contribution would exceed the sum of their individual parts.

We hope you will agree that expectation has been richly rewarded. Indeed, Blyth has asked that Hopkin be listed as lead author in order to signal the importance of his contribution in moving beyond the arguments sketched in the original Schapiro lecture. As editors, we have been very happy throughout this process – the talk, the essay, and now the publication. The Leonard Schapiro Lectures are meant to spark fundamental debate about comparative politics. We are grateful to Professor Blyth and particularly to Professor Hopkin for making this contribution such a success.

Recent work in comparative and international political economy has rediscovered the importance of distinct ‘growth models’ (Baccaro and Pontusson Reference Baccaro and Pontusson2016) and ‘macroeconomic regimes’ (Blyth and Matthijs Reference Blyth and Matthijs2017). These concepts draw our attention to the ensemble of institutions and ideas that produce distinct forms of capitalist accumulation in particular historical periods. Mark Blyth and Matthias Matthijs (Reference Blyth and Matthijs2017), in particular, have forged a link between the rise and decline of specific macroeconomic regimes/growth models and attendant forms of politics – specifically, the rise of populism across the globe in recent years.

Their argument is that the macroeconomic regime that governed the markets of the advanced capitalist democracies from the end of the Second World War until the mid-1970s produced a growth model that was particularly favourable to labour. This regime failed in the 1970s in the inflationary crisis of the period and ushered in a new regime that was much more capital friendly. That regime in turn failed in a crisis of deleveraging in 2008 but has nonetheless not yet been replaced by a new growth model, due to both the continuing power of capital and the interventions of globally important central banks. Blyth and Matthijs used this framework to explain how this second macroeconomic regime (c. 1977–2007) produced a ‘creditor’s paradise’ where low inflation and an ever-increasing asymmetry in the returns to capital over labour resulted in creditor–debtor stand-offs, both within and between countries (metropoles versus heartlands, northern exporters versus southern consumers), which is the mechanism that we use to explain the rise of populism today.

In this article, we wish to take this same framework in another direction to explore more fully the link between populism and growth regimes, for three reasons. First, populism as a political movement in Europe did not start with the 2007–8 crisis. It has been growing continuously since at least the 1980s in the form of Green parties, various National Fronts and an assortment of so-called Progress parties. Second, populism, in the form of a political claim that only the ‘big man’ can look out for the ‘little guy’, is not really the phenomenon Europe is experiencing (Müller Reference Müller2017). Rather, we argue here that such ‘big-man’ populism is merely one symptom of the collapse of traditional political parties and party systems, which is itself a consequence of what the growth regime of 1977–2007 did to the political parties that grew up under the first regime of 1945–77.

Drawing on earlier work that we have both authored on the shift from parties of mass integration to catch-all to cartel parties, we argue that there is a definite link between the evolution of growth regimes and changes in European party systems. Specifically, we will argue that the 1945–77 growth regime co-evolved with a particular type of party and party system: one that turned mass parties of integration into catch-all parties of electoral competition and public good provision. We then argue that developments in the post-1977 growth regime caused these party forms to become maladapted to their new environment, and as the new growth regime evolved it demanded further changes in party form in order to survive, the optimal form before the financial crisis being the emergence of cartel parties. This article will specify the causal logic behind these claims and use that to explain more fully the rise of populism in Europe in several contemporary cases. In short, rather than see the new politics of populism as solely related to post-financial crisis wage stagnation and the asymmetric costs of post-crisis adjustment, although that is certainly a part of the story, we extend this argument and see populism in Europe as an instance of party system transformation driven by the rise of anti-system parties claiming to challenge the neoliberal cartel.

Macroeconomic regimes

Macroeconomic regimes are historically specific combinations of ‘hardware’ (capitalist institutions) and ‘software’ packages (policy targets and the economic ideas that underpin them) that produce specific distributional and electoral outcomes. That is, if institutions are designed to produce specific policy outputs via specific targets, common targets should produce common institutions across cases, which is indeed what we find, in quite specific clusters, in two different periods, across the OECD countries. Table 1 represents these essential features.

Table 1 The Macro Regimes of the 1970s and Today Compared

Source: Authors (adapted from Blyth Reference Blyth2016: 220; Matthijs Reference Matthijs2016: 405–8); from Blyth and Matthijs Reference Blyth and Matthijs2017.

The post-war macroeconomic regime (1945–77)

In the immediate post-war era, corporatist institutions and domestically focused financial markets formed the hardware of capitalism, while various Keynesian-type ideas and a singular and shared policy target of full employment constituted the software powering the system. As Table 1 notes, full employment was the common policy target across states, even if different institutional means were deployed to get there. Inflation was not only tolerated, in several cases it was actively encouraged as a way of smoothing the distributional conflict between capital and labour (Pontusson Reference Pontusson1992; Swenson Reference Swenson1990). Investment in ‘real’ sector activities was encouraged, while finance’s ability to profit from arbitrage and leverage was kept firmly in check (Krippner Reference Krippner2011). The whole system relied upon high levels of consumption driving up demand, which would then drive wage growth, which would then force productivity improvements upon firms to pay for the wage growth (Mason Reference Mason2015; Meidner Reference Meidner1980). So that capital would play ball, not only was finance constrained by a lack of exit options, but labour was encouraged to be both large and organized, trading wage moderation as inflation control for real wage increases via structures of corporatist intermediation (Schmitter Reference Schmitter1974).

As a result, for the first time in history, and across the OECD as a whole, the bottom of the income distribution moved up, the top moved down, and the distribution as a whole ‘jumped’ upwards (Goldin and Margo Reference Goldin and Margo1991). The French called this period ‘les Trentes Glorieuses’, the Germans had an ‘economic miracle’, and the Italians had ‘il Boom!’ Whatever it was called, labour had never had it so good. This is why by the 1960s one could meaningfully talk of ‘the mixed economy’ and the ‘full employment universal welfare state’ being of a common type, despite national variations among them (Shonfield Reference Shonfield1965). This was a regime where no one outside of the readership of the Financial Times knew who ran the central bank, since the central bank in this period was oftentimes little more than the cheque-cashing agency for the treasury (Johnson Reference Johnson2016). It was a regime where parliaments legislated over huge areas of economic policy and fiscal policy was considered to be the primary policy tool of the state. However – and this is the part of the argument that we wish to develop in this article – this regime also both produced and was predicated upon a specific type of politics. One where parties mobilized large numbers of citizens in activities remote from elections, from social clubs to youth events to study groups. It was a world that rested upon a particular type of party, a form of party that was about to find itself ‘long and wrong’ for the post-1977 world.

Macroeconomic regimes, political parties and party systems

Modern political parties took form in the latter half of the nineteenth century through agitating for expansion of the suffrage. These ‘mass parties’ were both a response to, and a further stimulus for, the politicization of the working classes. Such an organizational form relied on numbers, attempting to make up in collective actions what it lacked in individually influential supporters. The rise of the mass party can thus be understood as an organizational form designed to organize and coordinate large numbers of activists, both within a given geographic area and across space, under conditions of mass suffrage. However, such an organizational form rather obviously begs some serious collective action problems, which were in turn overcome in two ways.

The first was the reinforcement of corporate identity among party members via ideology. Here the support of the mass party, and membership therein, was constitutive of the member’s identity, most likely driven or reinforced by the perception of opposition, or even persecution, from some other well-defined group or party. The other solution was policy, either in the form of support for particular political positions, or in the form of actual delivery of public services (for example, state provision of health care, or public support of church schools) that are of particular value to party members (Esping Andersen 1985).

Basing a party upon the ability to make such provisions over the long run was to prove both its signal strength and its ultimate weakness, as it was contingent upon the near permanent expansion of public goods made possible by an acceptant, or at least acquiescent, capitalist class. However, the success of such parties’ efforts to expand state welfare provisions, in order to expand and entrench their power, converted many of what were essentially ‘club goods’ into general public entitlements, which in turn led to a blurring of the social boundaries vital to any politics of identity.

The response to this problem was a movement towards ‘catch-all’ parties (Kirchheimer Reference Kirchheimer1966), which abandoned appeals to core constituencies while emphasizing the provision of public goods rather than party identity, alongside the competence of the party as the manager of the economy over transformations of that economy for partisan purposes. As a consequence, catch-all parties each sought to encompass an ever-increasing coalition in the hope of stabilizing their vote shares in the face of diminishing returns to policy distributions. However, in order to do so the supply of public goods had to increase past the possibility frontier the state operated on, especially in an environment where capital was no longer either able, or willing, to foot the bill. As such, catch-all parties became both increasingly unstable and increasingly unable to provide the goods that success depended upon.

The bug that killed the post-war regime

That it would go this way was predicted 30 years before it happened. There was a bug in the software, to continue the metaphor, in the workings of the institutions designed to produce both full employment and the catch-all form of politics that this growth model made possible. That bug was discovered in a famous short paper by the Polish economist Michał Kalecki (Reference Kalecki1943: 322–31). Kalecki, as is well known, argued that a policy of sustained full employment over the long run would consistently push up the median wage. Skilled workers at the top of the distribution would thus be able to capture extra rents due to labour markets being permanently tight (Blyth Reference Blyth2015). While this would please labour, it would lead to capital defecting from the post-war regime, for three reasons (Kalecki Reference Kalecki1943: 324–5).

First, at the firm level, management’s ‘right to manage’ would be undermined because sustained full employment would allow labour to move costlessly from job to job, pushing up wages further in the process. As such, labour discipline would decline, along with productivity, while labour’s ability to strike would be strengthened. Second, at the industry level, the only way that firms could hold onto skilled workers given such pressures would be to pay them more. But the only way that firms could do that would be to raise prices ahead of productivity. Doing so under conditions of full employment would ignite a wage–price spiral of cost-push inflation, as firms would seek to externalize the costs of their wage increases onto others. This would in turn ignite more strikes as workers realized that the wage increase they just secured would be eaten away by the inflation that their own actions were causing, thus destabilizing the system further. Third, as inflation accelerated, it would act as a tax on investment, which would retard present investment by dampening long-term investment expectations. The result, Kalecki predicted, would be a world where ‘a powerful block is likely to be formed between big business and rentier interests, and they would probably find more than one economist to declare that the situation was manifestly unsound. The pressure of all these forces, and in particular of big business, would most probably induce the Government to return to the orthodox policy of cutting down the budget deficit’ (Kalecki Reference Kalecki1943: 330).

Kalecki’s Reference Kalecki1943 account of the ‘bug’ in the software is an astonishing explanation of the flaws in the growth model of post-war capitalism and why it would endogenously undermine itself. His account also explains why the post-1970s regime was based around price stability rather than the goal of full employment (capital wanted its margins back) and why domestic institutions were re-engineered to facilitate that goal. After all, if inflation was too high and profits were too low, and capital did indeed find a plethora of supportive economists in the 1970s and 1980s that deemed the situation ‘manifestly unsound’, then the shift to a regime with opposing characteristics would be what one would expect.

Transforming the first growth regime

Strike activity across the OECD peaked in the late 1970s in a crisis of wage-driven inflation. Capital’s different fractions (exporters versus importers, finance versus manufacturers) were almost all damaged by inflation and effectively went on the capital strike that Kalecki predicted as a result of the collapse in the rate of return to capital. Capital organized, funded supporting economists and reoriented politics in the most inflationary-shocked states in a direction that stressed price stability over full employment as the core policy goal, as early as 1980 (Blyth Reference Blyth2002). At that juncture four lines of dissolution and reformation for the first growth model became apparent.

The first line of attack was the deregulation of finance and the consequent rise of capital mobility. While a significant amount of scholarly attention has been paid to the consequences of international capital mobility, and globalization more broadly, less attention has been paid to the consequences of deregulating banks in the context of very high real interest rates (Blyth Reference Blyth2015). Banks instantly became very profitable. And as financial markets integrated and inflation was wrung out of the system, the spread between the risk-free asset (the US 10-year Treasury Bond) and the effective real interest rate steadily declined. Money thus became much cheaper and more plentiful, which caused banks to chase riskier returns to maintain profitability, and crucially, to increase their leverage to keep making money on that declining spread (Blyth Reference Blyth2015). Financial assets to GDP skyrocketed across the system while the ability of states to bail those systems was undermined. As such, the stage was set for the crisis of 2008 once liquidity in such a hyper-levered system evaporated. But in the meantime, finance, not labour, ruled.

The second was the supply chain revolution and its effects on labour. In the prior regime labour and capital were both locally organized and locally vulnerable. Whenever capitalism hit a downturn, capital’s first-best strategy was to squeeze labour to preserve profits. However, given this mutual vulnerability, capital could only squeeze labour so far before strikes and disruption took their toll, or the state stepped in. Capital in all prior regimes therefore faced an institutional limit to how much labour could be squeezed, and had to instead innovate its way back to profitability. But this time it was different: in the new regime, labour stayed local but capital went global via financial liberalization and the supply chain revolution, with the result that the ability of labour to bargain with capital at home collapsed (Mason Reference Mason2015: 87–94).Footnote 1

The third line of attack was the rise of independent central banks and the shift to monetary policy dominance (Johnson Reference Johnson2016; McNamara Reference McNamara2002). As the literature advocating for this shift in policy and authority clearly stated, inflation is a time inconsistency problem endogenous to democracy (Posen Reference Posen1995, Reference Posen1998). As such, since fiscal policy in a Lucas-type world cannot work, the stress needs to be on autonomous monetary policy, preferably by politically insulated experts. The upshot is that parliaments get bypassed and fiscal policy is rendered toothless. Given these changes, it is little wonder that the parties and party systems made possible by this first growth regime found themselves at a sudden evolutionary disadvantage. Designed for a set of macroeconomic conditions that no longer existed, they had to either adapt their models to this new economic reality, or die.

How parties and party systems adapted to the second growth regime: the cartel party

If the end of the first regime signalled an environmental shift that would severely impact catch-all parties, there was one form of party, first identified by Richard Katz and Peter Mair (1995, also Reference Katz and Mair2009), that seemed singularly suited to this new environment: the cartel party. Originally conceived to explain the increasing reliance on state subventions by centrist European political parties, the model was adapted by Blyth and Katz (Reference Blyth and Katz2005) to explain the collapse of catch-all parties and the rise of a new form of party that seemed to secure its future by doing, and promising, less policy rather than more. Their basic model is as follows.

Assume a party system that is dominated by two catch-all parties and that each catch-all party has indeed attempted to maximize support through its expansion of public goods provisions (Meltzer and Richard Reference Meltzer and Richard1981). If we further assume that voters would prefer more public goods to fewer, but also assume that there is a defined fiscal limit beyond which such provisions cannot be made without creating a fiscal crisis, especially when capital is in revolt, then the catch-all strategy runs into an evolutionary dead end as a result of parties’ bidding wars. Two consequences follow. States cannot squeeze any more resources out of their societies for the production of public goods without harming growth itself (Bergh and Henrekson Reference Bergh and Henrekson2011; Tanzi and Schuknecht Reference Tanzi and Schuknecht2000). As such, policy competition becomes less feasible. Second, at the same time as reaching such fiscal limits, party members actually became a hindrance rather than an evolutionary advantage as the technology of elections moved away from mass participation to media marketing (Panebianco Reference Panebianco1988). Union blocs became less valuable than newspaper endorsements, television time and large private donations (Hopkin Reference Hopkin2004). In sum, as the costs of providing public goods began to exceed the capacity of states to provide them, the costs of running electoral campaigns increased beyond the capacity and willingness of the party on the ground to provide them.

Catch-all parties were then, first and foremost, products of the first growth regime where states were assumed to have primary responsibility for ensuring jobs and growth, and were also assumed to be able to marshal fiscal instruments to those ends (Kirchheimer Reference Kirchheimer1966). Unfortunately, as well as the material changes noted above hobbling such parties, a reformation in the way policymakers and their economic advisers thought about the economy occurred over the same period where market interventions of any kind were treated as anathema and inflation control was seen as the only goal worth pursuing (Blyth Reference Blyth2002). In such a world, catch-all parties and their attendant policies become counter-productive.

Given such an environment, catch-all parties engaged in three survival strategies: downsizing expectations, externalizing policy commitments and separating themselves even further from any defined constituency. The end result of which was to create cartel parties. Unfortunately, the problem with that strategy was that while the cartel party form was perfectly adapted to the environment of the second growth regime, when that regime ended in 2008, the cartel form persisted. But such a form was unable to respond meaningfully to the crisis, which allowed populist parties that had already grown up in the system in reaction to the cartel, and some entirely new ones, to really attack, and transform, European party systems.

Creating cartel parties and cartelized party systems

As noted above, given this new environment where catch-all strategies were obviated, parties had to find a new set of strategies to survive. The first was to downsize voters’ expectations. This occurred because all parties had an interest in reducing the policy commitments that had overextended them in the first place. Regardless of their political complexion, none of them could satisfy traditional demands for ever-increasing public goods provisions given the changed economic context (Pierson Reference Pierson1998). Party elites therefore began to ratchet down constituent expectations. In cartel terms, they were signalling to other players that they were limiting quantities and encouraging joint maximization. As such, if other parties did the same, they could cartelize the market and get more profit (hold on office) and security (minimal cost of electoral defeat) for less (lower policy commitments). How then does one ratchet down expectations?

The first mechanism was discursive. Catch-all parties of the left proclaimed their devotion to the free market and the global economy, despite all its draw-backs for their traditional constituencies. They did this because they had discovered a ‘third way’ or ‘die neue Mitte’ or ‘den enda vågens politik’ that in effect said states should not produce the public goods they had in the past because the market could do it better. Whether the market could in fact do it better was questionable. What was important was that the deployment of such a discursive strategy in part got states ‘off the hook’ for the production of such goods in the first place (Hay and Rosamond Reference Hay and Rosamond2002). While mass parties of the right with all their traditional distrust of the state had never been too comfortable with the production of public goods on an ever-broadening basis in the first place and had simply jumped on the ‘neoliberal’ bandwagon for ideological reasons, parties of the nominal left needed a justification for doing the same thing. Thus, in order to survive in a post-catch-all environment the rhetoric of ‘globalization made me do it’ (Hay and Rosamond Reference Hay and Rosamond2002) and various ‘third ways’ were employed (Giddens Reference Giddens1998). The second mechanism was institutional. Once in power, parties could signal their resolve to other players by creating institutional fixes to the problem of policy quantity reduction, thus locking in expectation reduction, and thereby credibly committing to cartelization of the political market as a whole (Blyth and Katz Reference Blyth and Katz2005). The logic of central bank independence illustrates this nicely.

According to the new software written to power the second growth regime, politicians, through their overproduction of public goods, tended to mesh the electoral cycle to the business cycle in order to get re-elected. Given this, politicians should not be given the instruments to reflate the economy in the first place. The best way of assuring this was then to devolve monetary policy to unelected central bankers with long time horizons as only such a group would have preferences that would produce low inflation and thus safeguard growth (Drazen Reference Drazen2002). In practice central bank independence did not entirely preclude stimulatory policies, but these took the form of credit expansions facilitated by regulatory reforms, and as such were embraced by financial markets, who were more tolerant of privatized Keynesianism (Crouch Reference Crouch2009; Hay Reference Hay2013) than the state-led variety.

But such institutional fixes are the equivalent of binding quotas over the quality as well as quantity of polices that a group of parties can produce. Empirically, having an independent central bank means that politicians are no longer responsible for either creating or managing economic outcomes. As such, they cannot be held accountable for their effects. Devolving policy problems up to supra-national organizations or down to regional assemblies does much the same thing (Smith Reference Smith1997). Policy externalization to independent institutions insulates politicians from voters’ preferences and effectively curtails the supply curve for policy, thus cartelizing the party system while creating a new form of party. By truncating the policy supply curve in this way, parties are encouraged to maintain the status quo rather than promote change. Politics becomes a contest between political leaders who compete on cosmetic and symbolic lines but who are generally agreed on the basic framework of the political economy and the power relations underpinning it.

The third mechanism was internal to parties themselves. Given the declining relevance of the mass base, or even individual supporters, incumbent party politicians could, and indeed increasingly did, effectively use externally (private) or internally (public) generated funds to ‘hire’ voters to vote for them at election time. After the election, given agents’ commonly diminished expectations and the institutionally enshrined lack of accountability, voters have no effective power over the politicians as their sources of funding and thus re-election lie away from traditional mass organizations such as unions and individuals towards large corporate and other donations (Hopkin Reference Hopkin2004). Party responsiveness through grassroots organization was replaced by extensive political marketing to sell political leaders on the basis of personal charisma and technocratic competence. Attempts were made to compensate party members happy for their diminished status, in the form of new opportunities to participate in internal candidate and leadership selection, but these processes were mostly tightly controlled by party elites (Hopkin Reference Hopkin2001).

If one adds these internal organizational changes to the restriction of the supply curve for policy-facing parties discussed above, then we find that these three interrelated strategies – downsizing constituent expectations, externalizing policy commitments and separating the party from any defined constituency – have the net result of transforming catch-all parties into cartel parties whose purpose is precisely not to govern. Like in the limited liberal state of old, the party’s job was to allow markets to govern society, not act as the agent of society governing the markets. While this form of party and party system was an evolutionary rescue for the catch-all party and was perfectly adapted to and catalysed by the growth regime of the period, it had three critical weaknesses.

First, governing nothing is fine so long as nothing is wrong. When the system that has engendered these party forms has a heart attack, and these party forms have neither tools nor ideas on how to effectively respond, voters notice. Second, the cartelization of party systems over the period 1977–2007 produced the classic response to cartels – entryists. Whether in the form of parties that wanted to transform the system or simply get a piece of the cartel action, the formation of cartels necessarily creates the conditions for the rise of challengers over the long run. Third, if the first growth regime came apart over the distribution of the costs of inflation, the second came apart over the costs of inequality in its various guises (housing, income, mobility, opportunity, assets). Cartel parties were designed to be parties that governed over less and less. As such, they were unable to address the very real problems that had grown up over the previous 20–30 years that these parties studiously ignored (Mair Reference Mair2007). It was in this fertile ground that populism grew.

European populism as the failure of cartel parties and cartelized systems

Populism is a much-abused term, and its conceptualization is disputed. Populism is usually defined as an anti-elitist discourse that purports to represent some morally charged idea of the ‘people’ as a whole while condemning existing institutions for betraying or failing to properly represent the people. In its right-wing form, it also draws on authoritarianism and nativism (Mudde Reference Mudde2007) and has a strong tendency towards charismatic leadership and personalism (Mueller Reference Müller2016). Populists often define the people in opposition to some other definable ‘out-group’ and evoke moralistic definitions of who the ‘real’ people are (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017; Mudde Reference Mudde2004). All of these features can be observed in some of the parties we discuss in this article, but they are not in themselves the focus of our attention. We argue instead that parties challenging the neoliberal cartel can be considered populist because, like the early populist movements of the late nineteenth century in North America and Europe, they express ‘a powerful sense of opposition to an establishment that remained entrenched and a belief that democratic politics needed to be conducted differently and closer to the people’ (Rovira Kaltwasser et al. Reference Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 5). In other words, they emerged and grew on the back of a critique of the establishment and a commitment to replace it with a different form of governance based more explicitly on the popular will. This opposition to the cartel parties and their leaderships, and the demands for politics to be more responsive to the people in the broadest sense, are what characterizes the parties we describe as populist in this analysis.

The definition we are working with allows us to extend our inquiry beyond the right-wing anti-immigration parties that have absorbed most of the attention of scholars of populism (for a review, see Golder Reference Golder2016) to other movements that share a critique of the cartel party system and a demand for politics to engage with popular concerns, but which do not adopt a reactionary or authoritarian discourse. This avoids reducing populism to its right-wing nationalist variant and therefore dismissing it as reactionary and illegitimate, and it allows us to identify the more general causes for the rise of anti-establishment parties as disparate as the Front National in France, UKIP in the UK, Syriza in Greece and the Five Stars Movement in Italy. The extensive conceptual discussion among populist scholars around the true nature of populism lies outside the scope of this article (for a review, see Kriesi Reference Kriesi2014).

From the perspective of the cartel party model, populism is a predictable reaction to the increasingly undifferentiated policy positions of the mainstream parties and the growing detachment of elected politicians from civil society (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995). Not only are voters less likely to be tied to parties institutionally as activists or members of related associations or unions, they are also less likely to identify with them ideologically as a result of the increasingly catch-all nature of political competition (Blyth and Katz Reference Blyth and Katz2005). This would lead us to expect more voters to be available to be mobilized by anti-cartel parties, especially if there is growing dissatisfaction with the more established parties, as their electoral decline seems to suggest. However, this in itself tells us little about who will support such parties, and under what conditions. To do so, we suggest a political economy explanation which sees contemporary European populism as primarily a reaction to the neoliberal growth model, and we present evidence from party positions, electoral performance and patterns of economic growth and income distribution that indicates the success of populism is closely related to the ways in which market economies distribute income, wealth and risk.

Populist parties and the rejection of market liberalism

Not only do populist parties reject the cartel and its governing style, but they also reject neoliberalism and its emphasis on unfettered markets. The cartel parties’ convergence around the rejection of activist policies of public good production and economic redistribution created a space for populism to demand a less restrictive and more interventionist approach. If cartel politics is about protecting the market and private property from political interference, populistic politics instead demands that government ‘do something’ to address the inequalities and insecurities generated by inadequately regulated capitalism (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017: 370). This ‘something’ varies, ranging from ending austerity and expanding public provision of welfare and employment on the left, to restricting immigration to protect native workers on the right. Left-wing populism understands the ‘people’ in class terms, whilst right-wing populism understands the people as a national or ethnic group (Mény and Surel Reference Mény and Surel2002). What is common across this range is the belief that government can be a force for the defence of the people, and this implies a rejection of the individualistic and laissez-faire ethos of contemporary neoliberalism. Populism is therefore counterposed to liberalism in the economic sphere: it is democratic illiberalism (Pappas Reference Pappas2013).

This conceptualization of populism as essentially opposition to market liberalism is well entrenched in economics and public choice scholarship. William Riker (Reference Riker1982) defined liberal democracy as limiting the power of government by focusing on the protection of individual rights such as private property, whilst populist democracy reflected the use of popular pressure to shape and redefine the market through government action, potentially undermining these rights. Recent economics research on populism describes it as anti-market policies that are supported by many voters, even though the policies are against the economic interests of this majority, such as inflationary pursuit of growth and fiscally reckless redistribution (Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Egorov and Sonin2013; Dornbusch and Edwards Reference Dornbusch and Edwards1989; Guiso et al. Reference Guiso, Herrera, Morelli and Sonno2017). From a very different normative perspective, this understanding of populism connects with the movement in late 19th-century America that gave rise to the term (Kazin Reference Kazin1995). In our view, the populist forces, in their different guises, share the ambition to use government to respond to popular demands, through economic and social policies to protect the population, or part of it, from the inequality and insecurity generated by markets. Populism in this sense is therefore more to do with arguments about how the economy is governed than with definitions of who the ‘people’ are.

The rejection of unfettered markets from the parties of the populist left, most of which exhibit various degrees of anti-capitalist rhetoric, is easy enough to demonstrate. Parties such as Syriza in Greece, Podemos in Spain, France Insoumise and the UK Labour Party since the Corbynite takeover have very clearly demanded an end of austerity and a shift in economic policy and regulation away from the preference for financial interests and in favour of a redistribution of wealth and income towards the non-wealthy majority in society. Opposition to post-crisis austerity measures has been an important focus of these parties, and in the southern European case this has taken the particular form of protest against the imposition of welfare cuts and structural reforms as conditions of financial assistance during the euro debt crisis. Although demands to reform the workings of European Monetary Union so that the costs of adjustment do not fall mainly on wage-earners and the unemployed have been very present in the discourse, left populist parties have tended to avoid overt Euroscepticism, demanding instead that Europe should take a more social and redistributive turn (Kouvelakis Reference Kouvelakis2016; Ramos and Cornago Reference Ramos and Cornago2016).

The anti-market positions of right populist parties are less obvious, since these parties rarely express hostility to the market system in principle, and sometimes are associated with positions typical of the pro-market right, such as lower taxation, strong defence of private property and sympathy for business, especially small companies and the self-employed. However, right populists often emphasize protectionist market-curbing policies, most obviously restrictions on immigration which protect native workers from international competition in the sheltered parts of the economy, and welfare chauvinism, or preference in social protection for citizens over migrants, often supporting very generous welfare provision for the former (Ennser-Jedenastik Reference Ennser-Jedenastik2018). Whilst these parties’ illiberal attitudes on social and cultural issues receive abundant attention, their illiberal attitudes on economic issues are often missed, but imply a rejection of the dominant thinking underpinning the neoliberal growth regime.

The anti-market positions of some other anti-cartel parties are more ambiguous. Perhaps the main exception is Emmanuel Macron’s En Marche, which can be considered a challenger party only in that it is a new organization with largely new political personnel, but which appears wedded to market liberal thinking for the most part. The Italian Five Stars Movement lacks any clear ideological anchoring, focusing mainly on opposition to the Italian political establishment, but its signal policy proposal in the 2018 election was the Universal Basic Income, and Euroscepticism and hostility to euro-driven austerity have been a key part of their discourse. The ethno-regionalist parties in Scotland and Catalonia have also mostly shunned economic protectionism, although there is an implicit welfare chauvinism in the Catalan nationalists’ complaints about net contributions to Spanish social spending (Miley Reference Miley2017) and the Scottish nationalists are favourable to higher social spending and increased taxes for high earners. In Italy the Northern League under Salvini has developed into a typical right populist party focusing particularly on immigration and flirting with Euroscepticism and protectionism.

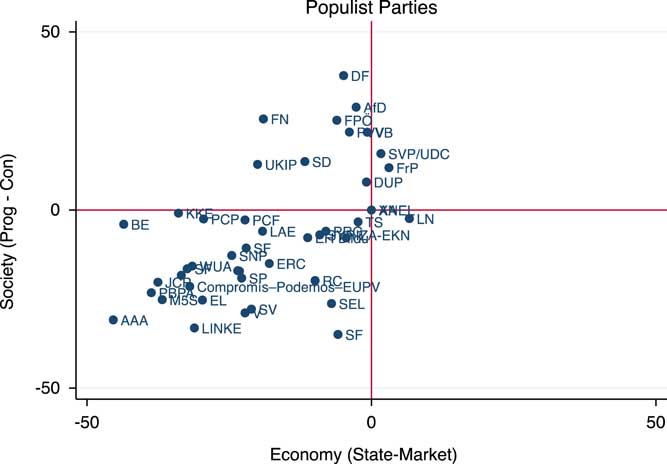

This can be illustrated using data from party manifestos. In Figures 1 and 2, we present the average policy positions of West European parties in recent election manifestos on two dimensions, a state–market dimension on economic policy, and a progressive–conservative dimension on social policy (positive numbers are more pro-market and conservative). The distinctive positions adopted by the populist parties in Figure 2 stand out clearly in comparison to the cartel parties in Figure 1. The cartel parties, representing the liberal, Christian democratic, social democratic and mainstream conservative positions occupy a narrow range around a broadly centrist position in Figure 1. In Figure 2, the populist parties on both left and right mostly adopt a more statist position on economic policy than their counterparts amongst the cartel parties. Right populists have more socially authoritarian positions than mainstream centre-right parties, and more statist positions on economic policy, whilst left populists have on average similar positions on the social dimension, but more statist positions on economic policy than the centre-left cartel parties. In sum, we see that the populist parties are occupying spaces left vacant by the cartel’s rejection of statist positions on the economy.

Figure 1 Cartel Parties on the Social and Economic Policy Dimensions

Figure 2 Populist Parties on the Social and Economic Policy Dimensions

In short, opposition to the policies and institutions of the neoliberal growth regime, albeit from widely varying ideological perspectives, have been a common feature of almost all the parties that have won significant vote shares by successfully challenging the party system cartel. The populist wave, then, is more than simply a rejection of existing elites and a demand for greater attention to the neglected populace; it is a challenge to a model of governing capitalism in which elected politicians have little capacity for acting on markets to protect the people from threats to their incomes and security.

This challenges standard understandings of electoral change based on assessments of parties’ responses to changing voter preferences or shifts in electoral cleavages (Beramendi et al Reference Beramendi, Hausermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; Hall Reference Hall2018). These approaches see political parties as broadly representative and responsive organizations which may at times find themselves slow to react to changes in electoral preferences or structural changes in the economy which undermine established patterns of electoral mobilization. Here instead we see current political and electoral upheavals as a response to a much broader failure of the party system, or at least the established parties of governments and mainstream opposition. The neoliberal growth regime, rather than simply failing to represent a sufficiently wide coalition of social forces, has instead tended to shun representative government per se in favour of a very narrow conception of what governing a capitalist economy involves.

The distributional consequences of this regime, far from simply shifting resources between different electoral coalitions, were much more profound, presiding over a major shift in resources from the non-wealthy majority to the minority that owns the bulk of capital assets (Piketty Reference Piketty2014). As around 10 per cent of national income in most Western countries has moved from the labour share to the capital share since the 1970s, the majority of voters have simply been excluded entirely from most of the income gains produced, and for sizeable minorities in a number of countries, living standards have actually declined. Added to the vastly skewed response to the global financial crisis, focused on bailing out financial interests with barely any popular consultation (Tooze Reference Tooze2018), the ingredients for a fundamental electoral shift away from the party cartel to populist outsiders are easily observed. However, there are important variations in the extent of this distributional shift, and these variations are strongly correlated with the success of populist parties in the post-crisis environment.

Explaining populist impact: the bigger the crash the harder the fall

Showing that populists reject the neoliberal growth model does not in itself tell us anything about the causal relationship between the neoliberal growth model and populism. Indeed, the role of ‘economic anxiety’ in encouraging voters to vote for populist candidates has been a subject of intense debate (for example, Guiso et al. Reference Guiso, Herrera, Morelli and Sonno2017; Springford and Tilford Reference Springford and Tilford2017). The main rival hypothesis relates to the generic notion of ‘identity politics’, with particular emphasis on immigration as a source of cultural anxiety which has led voters to reject the party cartel’s broadly liberal approach to borders and labour market access for migrants (Goodhart Reference Goodhart2017; Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2016). It is beyond the scope of this article to resolve this debate but we briefly present here some powerful comparative and temporal evidence for the importance of the economic consequences of the neoliberal growth regime.

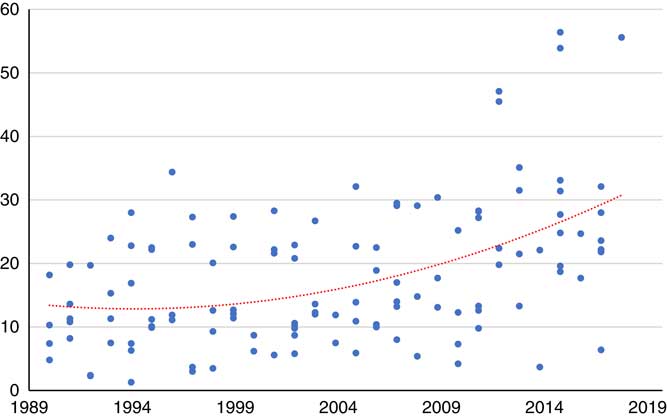

Figure 3 charts vote shares for parties from outside the cartel over the period since 1990 in Western Europe (each data point marks the total vote share for all the non-cartel parties in each country where an election was held in that year). Anti-cartel parties are defined as those outside the main party families present in the European Parliament and represented by internationals (that is, conservative, Christian democratic, socialist, liberal and mainstream Greens). They include both right-wing populist and nationalist parties, parties of the radical left and secessionist parties in multinational states, and other miscellaneous parties identified in the literature as representing anti-establishment positions. The trend is clear, in that the average vote share for anti-cartel parties more than doubled over that period. What is also clear is that the maximum extent of anti-cartel support increased too, especially after the global financial crisis, with anti-establishment parties even winning the majority of the vote in several cases.

Figure 3 Populist Vote Share, 16 European Democracies, 1990–2018

Source: Data from Hopkin (Reference Hopkin2019).

Note: The countries included are the EU-15 excluding Luxembourg, plus Norway and Switzerland.

The period of financial crisis, and then prolonged recession since 2008, has served as a proximate cause of the populist wave, but the seeds of destruction of the cartel model were present some time before that. As cartel parties became detached from society, new political forces emerged to challenge them: on the right, populist parties mobilizing around the issue of immigration won an increasing share of the vote across much of Western Europe; on the left, Green parties and other left alternative forces made (usually smaller) gains, while ethno-regionalist parties also grew their vote share in some European regions. Whilst the mainstream cartel parties presided over economic growth, however unevenly distributed, they were mostly able to form governing coalitions without having to call on the populists (although in Norway, Denmark and Austria right-wing populists did enter government in the early 2000s).

But the oligopoly did not survive the financial crisis and imposition of austerity measures after 2009, precisely because the cartel model became incapable of delivering even the lacklustre growth in average living standards that preceded it. The policies adopted by more or less all the major European democracies focused primarily on restoring order to financial markets and containing government debt but were entirely unsuccessful in sparking recovery for wage-earners. As this failure became apparent, and years passed with incomes struggling to return to pre-crisis levels in many countries, voters demanded alternatives, defeating incumbent parties and handing power to the opposition. Yet opposition parties from inside the cartel were incapable of delivering policy change. They simply maintained the restrictive policies of their predecessors and insisted that nothing more could be done to protect voters from the consequences of the crisis, except ‘structural reforms’ that for the most part increased economic vulnerability (Hopkin Reference Hopkin2015). The failure of conventional government turnover to make a difference created an opening for alternatives from outside the cartel, in the form of parties opposed to market liberal policies.

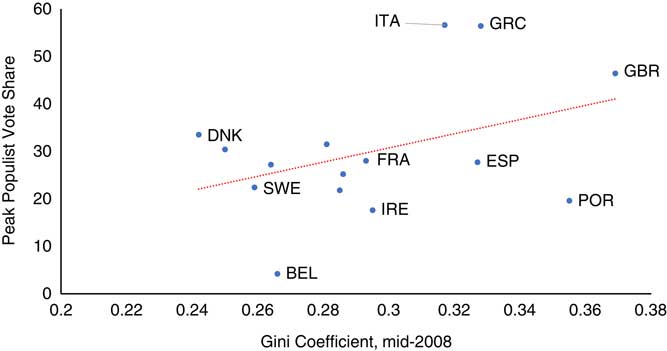

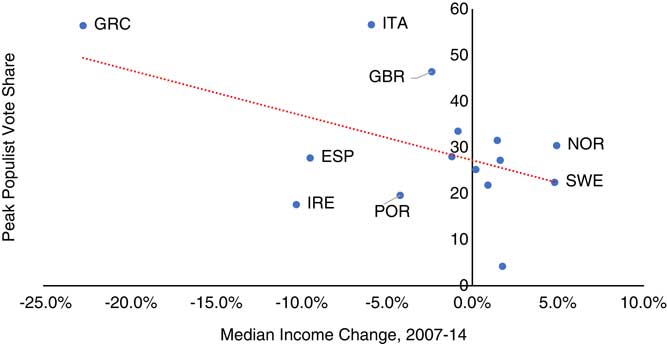

Further evidence of the connection between populism and the consequences of the neoliberal growth regime can be found in the distribution of populist successes across countries. The countries where populists have won big enough vote shares to win power have been the very same countries where the most voters have suffered the consequences of rising inequality and falling living standards. The populist challenge to the cartel builds on the distributional consequences of the neoliberal growth model by mobilizing the social groups who lose out under existing arrangements (Rodrik Reference Rodrik2017). The larger the share of the electorate suffering declining living standards, the greater the potential reservoir of support for populist parties articulating rejection of the growth model represented by the incumbent cartel parties. At the most basic level, inequality works as a reasonable proxy for the size of the electorate that could potentially be mobilized against the neoliberal growth model. Figures 4 and 5 shows that economic distress predicts the share of the vote won by populist or anti-system parties in recent elections in European states. Figure 4 shows the positive correlation between pre-crisis inequality and the populist vote in the most recent elections in Europe, whilst Figure 5 shows the negative correlation between compound wage growth after the crisis and the high point of populist support up to 2018.

Figure 4 Inequality and Populist Vote Share

Source: Inequality: Gini coefficients, disposable household income, 2008 OECD data, www.oecd.org/social/income-distribution-database.htm

Note: For Great Britain, populist vote includes Labour under Jeremy Corbyn, UKIP and secessionist parties.

Figure 5 Median Income Growth and Populist Vote Share

Source: Wage growth: OECD data, www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/employment/oecd-employment-outlook-2016_empl_out look-2016-en#.We3r8q3MyA9.

Note: For Great Britain, populist vote includes Labour under Jeremy Corbyn, UKIP and secessionist parties.

The more advanced welfare states, especially the smaller countries of continental Europe and Scandinavia, have long had significant right-wing populist parties (and often small left radical parties), whereas the countries with higher inequality have not. However, in the post-crisis context the picture is very different, with dramatic increases in populist voting in high-inequality countries such as Greece, Italy, the UK (measured either as support for populist parties including Labour after 2015 or as support for Brexit in the referendum) and Spain. Pre-crisis inequality is also a good predictor of post-crisis economic performance. The advanced welfare states have also tended to see better wage growth since the crisis, whilst some of the high-inequality countries have seen average living standards stagnate or fall since the crisis. Figure 5 shows that wage growth is again negatively correlated with populist support, even though some countries with traditions of significant populist vote share have performed better than average. In short, inclusive economic growth is generally bad for the prospects of populist parties and good for the party cartel, but a combination of inequality and poor growth is a good predictor of an increased populist vote.

Interestingly, though, there are also significant variations in the groups mobilized and the political forces that emerge to challenge the cartel across countries (Schwander Reference Schwander2018). Where policies and institutions are effective in protecting citizens from the threats and risks of the neoliberal model, populist reactions have tended to be less marked. The variations of welfare regimes across Europe explain which groups are most open to being mobilized and which ideologies and discourses are most likely to be successful in attracting the support of unhappy voters. Here we distinguish between coordinated market economies (Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001), ranging from the egalitarian Scandinavian social democracies to the continental Bismarckian welfare regimes, mixed market economies in southern Europe (Molina and Rhodes Reference Molina and Rhodes2007), and liberal or residual welfare states with limited, largely means-tested systems of social protection such as the UK, described by Gøsta Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1985) as ‘liberal’ welfare regimes.

In the global financial crisis, these countries all experienced economic shocks, but with very different intensity and duration. The coordinated market economies were creditor countries running often very high current account surpluses, and therefore less dependent on domestic demand. The liberal welfare states of north-western Europe, and the mixed market economies of the south, were all debtor countries which suffered very deep contractions when the flow of external credit abruptly stopped in 2007–8. The debtor countries suffered a much greater hit to living standards, although this hit was distributed differently across the different welfare state types. These variations predict different types of subsequent populist reaction.

In the more advanced welfare states, populism has mostly assumed a nativist form, focused on protecting the relatively successful arrangements for production and income distribution from the pressures of new arrivals who often require greater support and face problems accessing labour market opportunities. Blue-collar workers and small business owners, and especially older citizens with lower levels of education, back right-wing populists in countries such as the Netherlands, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland, Germany and Austria (Hoerner and Hobolt Reference Hoerner and Hobolt2017). The appeal of these parties focuses heavily on an anti-immigrant discourse, advocating restrictions on the influx of refugees and the exclusion of migrants from full social citizenship rights. This is a very defensive form of populism, wary of the risks the neoliberal model poses to the inclusive growth these countries have achieved in the post-war period. The growth in these parties since the financial crisis has mostly been moderate.

In the main European case of a residual welfare regime, the UK, nativist populism was traditionally absent, and has grown rapidly since the crisis, taking particular aim at international trading arrangements and the migrant threat to the labour position of native workers, with less emphasis on protecting welfare arrangements, which are mostly limited and oriented towards greater private provision. This is expressed in part through the Brexit vote, which leveraged the unhappiness of older, less-educated voters with the loss of secure employment resulting from foreign competition, often blamed on migration (Becker et al. Reference Becker, Fetzer and Novy2016; Curtice Reference Curtice2017; Goodwin and Heath Reference Goodwin and Heath2016). But the generalized insecurity of the liberal market economies also generated a left form of populist reaction appealing to younger and more educated voters exposed to the unpredictability of the ‘gig economy’, damaged by austerity policies and burdened with student debt and the high cost of housing. The support base of Jeremy Corbyn consists largely of these groups. In the liberal countries, the cartel is attacked from both sides, protecting as it does the interests of only a wealthy minority of the electorate, the only sector to make real gains since the 1970s, and the only sector bailed out after the financial crisis.

In the mixed market economy model of southern Europe, populist voting has also risen sharply, but mostly not in a right-wing nativist form. Southern European welfare arrangements create deep divisions between labour market insiders and outsiders (Bentolila Reference Bentolila, Dolado and Jimeno2012; Ferrera Reference Ferrera1996; Picot and Tassinari Reference Picot and Tassinari2017), the former enjoying the protections typical of advanced welfare states, the latter exposed to the worst form of labour market insecurity. These countries mostly enjoyed high and broadly inclusive growth until the financial crisis, but the draconian austerity policies and labour reforms imposed by the European authorities after the crash damaged the living standards of most groups, and particularly younger voters at all educational levels. The dominant political response here is left populism, with groups such as Syriza in Greece, Podemos in Spain, and the left coalition in Portugal mobilizing mostly younger voters denied access to employment opportunities by the demand-sapping policies imposed by Europe (Fernández-Albertos Reference Fernández-Albertos2015, Kouvelakis Reference Kouvelakis2016; Ramiro and Gómez Reference Ramiro and Gómez2017). Although the extreme right-wing Golden Dawn made gains in Greece in the early 2000s, and the populist right has had recent success in Italy, anti-immigrant and nativist sentiment has been relatively less relevant in southern Europe and the political challenge to the policy orthodoxy of the cartel has taken a broadly progressive and social democratic form, demanding an end to austerity and action at the European level to stimulate growth.

There are some cases that fit awkwardly into this framework – France and Italy appear to combine features of all three types – but it is a useful approximation of the broad pattern across countries. In terms of variation over time, the rising inequality and diminishing economic security characteristic (one could say by design) of the neoliberal growth model matches the declining support for mainstream political forces signed up to the policy orthodoxy that underpins it. The financial crisis constituted a hammer blow to this particular set of arrangements, but the signs of stress were already visible much before then.

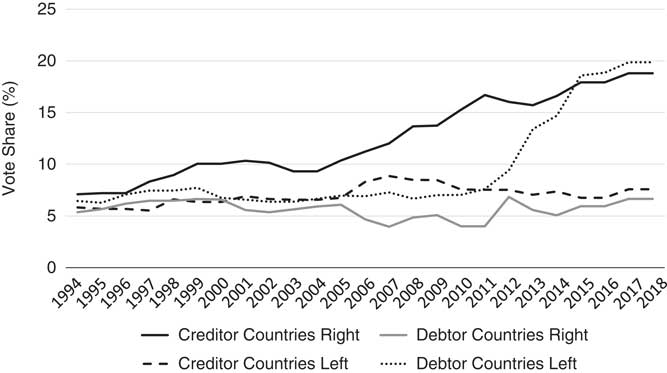

Figure 6 illustrates how the distinction between types of welfare regimes correlates with the degree of success of different kinds of populist party. If we distinguish between creditor and debtor countries we see distinct trajectories of populist support. In creditor countries (mostly in northern Europe), right-wing populism predominates, and the average vote share rises only moderately after the crisis, whilst left-wing populism has lower vote shares and barely changes over the period. In the debtor countries (southern Europe and the British Isles) the opposite pattern prevails: right-wing populism has low and stable average vote shares, whilst left populism enjoys spectacular growth after the financial crisis and resulting austerity kicks in. The support base of the neoliberal growth model may be crumbling across the European democracies, but the political reaction to its crisis is pointing in very different directions.

Figure 6 The Populist ‘Crocodile’: Left and Right Populist Vote Shares, Creditor and Debtor Countries

Source: Hopkin (Reference Hopkin2019).

Note: Left populist category contains all challenger parties not on the nativist right: left and Green parties, non-nativist secessionist parties, and other ‘catch-all’ parties.

Conclusion: politics beyond the cartel

Different growth regimes have their own distinctive patterns of electoral politics. The neoliberal era in Western democracies coincided with a decline of the 20th-century mass party, and the convergence of mainstream governing politicians around a restrictive vision of what government could do to shape the economic cycle and the income distribution. As parties offered their voters fewer and fewer concrete benefits, and citizens were encouraged to think of themselves as participants in a market, the connection between formal politics and civil society weakened and elections were increasingly fought around minor policy differences and symbolic identitarian issues. Whilst elections appear to matter less and less for the conduct of policy, the development of the neoliberal growth model generated increasing inequality and insecurity among a large part of the population, especially, but not exclusively, middle- and lower-income groups. The collapse of growth after the financial crisis sealed the deal.

Populism is then neither simply a response to economic globalization (Rodrik Reference Rodrik2017) nor a reaction to the perceived threats to entrenched cultural identities brought by mass immigration (Goodhart Reference Goodhart2017; Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2016). It is predominantly a demand for action from politicians who have hidden behind the imperatives of market forces and technocratic control of macroeconomic policy. For this reason, populist challenger parties do not subscribe to any uniform economic strategy: some combine neoliberalism with economic protectionism, some focus simply on restricting immigration, others demand a loosening of the monetary and fiscal strictures imposed by technocrats, whether in supranational authorities or national central banks. They have in common a demand for political change that the party cartel has been unable or unwilling to express, although the dramatic shifts in the politics of the Labour Party in the UK, the Republicans in the US and the Catalan nationalist parties in Spain show that established parties can embrace populist demands when placed under pressure.

The current populist wave may not lead to a radically different growth model. Indeed, the success of Donald Trump in the US and Brexit in the UK do not in themselves suggest any significant change, except in halting moves towards further international economic integration. Trump remains wedded to the tax-cutting, pro-finance agenda of the Republican elite, whilst the UK Conservative Party shows no signs of seriously embracing a different economic model for post-Brexit Britain. The Catalan nationalists demand cultural recognition and fiscal advantages rather than a genuine critique of the open economy model adopted in Spain since the establishment of the euro. Even the radical left Podemos has retreated from its initial anti-euro rhetoric in order to pursue a more expansive electoral strategy (Ramos and Cornago Reference Ramos and Cornago2016).

The connection between the changing political economy of Europe and the transformation of its electoral politics is a methodological challenge. In this article we have limited ourselves to establishing its plausibility by looking at the nature and timing of these changes and showing the following: that established political parties have been in organizational and electoral decline throughout the period of the neoliberal growth regime, a decline dramatically accelerated by the global financial crisis; that these parties have converged around the ideas and policies underpinning this regime and failed to respond adequately to the crisis; and that the new parties that have challenged the established party cartel have also challenged these neoliberal ideas and policies.

The political cartel that underpinned the neoliberal growth model is falling apart, but the configuration of financial, regulatory and productive forces that have benefited from it remain intact. Threats of disinvestment have greeted the Brexit and Catalan revolts and the recent election of a populist government in Italy, illustrating the ways in which free capital movement constrains the political choices available to democratically elected authorities. If our failed growth model is to change, it will require even more far-reaching political turbulence than we have witnessed so far.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Erik Jones and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article.