In China, there are still huge income disparities between urban and rural areas. In 2020, the urban–rural income ratio was 2.56, which was a slight narrowing from 2.79 in 2000.Footnote 1 This gap is a consequence of the dual urban–rural system as, in the past, China's economic development strategy greatly favoured growth in urban areas at the expense of rural regions. Hukou 户口, a household registration system that gives each citizen either agricultural (rural) or non-agricultural (urban) status, further perpetuates urban–rural inequality by defining citizens’ rights and entitlements on the basis of their categorization. Urban hukou holders have better access to social welfare and services compared to their rural counterparts.Footnote 2 The wide income gap also leads to a higher concentration of poverty in rural areas. Rural poverty differs in level and nature from urban poverty. In rural areas, structural factors such as a hazardous natural environment and a lack of infrastructure for economic development are the primary causes of poverty,Footnote 3 whereas in urban areas, unemployment, disability, illness and old age are the main reasons why people fall into poverty.Footnote 4

A means-tested cash-transfer programme is an effective tool to alleviate poverty.Footnote 5 To provide a safety net for those living in poverty, China operates the world's largest means-tested unconditional cash transfer programme: the Minimum Livelihood Guarantee Scheme (dibao 低保). Owing to its decentralized nature and China's prominent urban–rural divide, the dibao programme has varied across urban and rural areas in many aspects since its inception, including in its eligibility thresholds (dibao biaozhun 低保标准) and administrative procedures. Against the backdrop of promoting coordinated urban–rural development, the central government has encouraged local governments to integrate their urban and rural dibao schemes into a unified programme since 2011.Footnote 6 Compared with the rapid establishment of the urban dibao programme in the 1990s,Footnote 7 the pace of implementing a unified urban–rural dibao threshold has been slow: only 17.4 per cent of prefecture-level administrative divisions (58 out of 333) followed this route between 2011 and 2019. This phenomenon leads to an intriguing puzzle: what drives or hinders a local government's choice to unify the dibao thresholds in urban and rural areas?

Both internal features and external forces shape policymaking at the local level. For internal features, a stream of literature suggests that in China, the problem-solving and social welfare functions of social policy remain subordinate to economic and political functions.Footnote 8 In particular, prior literature has found that local variations in dibao-related indicators (for example, in coverage, thresholds or expenditures) were primarily driven by fiscal factors (for example, capacity, dependency and expenditure on other items).Footnote 9 Some studies further show that dibao served as a tool to achieve other policy objectives, such as combatting corruptionFootnote 10 and maintaining social stability.Footnote 11 The findings that fiscal factors and other policy objectives drove local variations in the dibao programme reflect the peripheral role that social welfare indicators play in the cadre evaluation system (CES hereafter). In China, central or higher-level governments retain tight control over cadre mobility through the CES, in which hard targets (such as economic growth and revenue generation) and priority targets (for example, anti-corruption efforts and social stability) are prioritized over soft targets such as social welfare.Footnote 12 Social policies such as the dibao programme remain peripheral within the CES because they consume fiscal resources that could otherwise be used to promote economic growth.Footnote 13

The central government's growing awareness of the unintended effects that an all-out economic growth agenda imposes on social development has led to a greater emphasis on a more sustainable development path that balances economic growth and social welfare.Footnote 14 In this context, a number of studies examine beyond internal features and investigate the influences of external factors on social policy outcomes.Footnote 15 They find positive effects from top-down pressure (vertical administrative command) and horizontal competition (the influence of adoption by neighbours) on dibao thresholds,Footnote 16 the establishment of urban dibao programmesFootnote 17 and the integration of health insurance programmes.Footnote 18 In particular, positive horizontal effects indicated that “racing to the top” existed in this social welfare policy domain.

How do internal features, top-down pressure and horizontal competition jointly shape local governments’ decision to adopt a social policy aimed at enhancing urban–rural equity? For internal features, are economic growth and revenue the overriding factors driving local policymaking? For top-down pressure, how do local governments respond to vertical directives with varying levels of coercive powers? Within the horizontal mechanism, do local governments race each other to be the first to adopt a social policy?

Our study answers these questions by constructing and analysing an original panel dataset on the adoption of unified urban–rural dibao thresholds in 336 prefecture-level divisions in China between 2011 and 2019. It contributes to the scholarly debates on forces that drive decentralized social policymaking in the context of urban–rural integration. First, it sheds light on the facilitators and barriers to delivering a decentralized social assistance programme by providing empirical evidence from China, the largest developing country in the world. A key issue for cash-transfer programmes in a decentralized context is how to incentivize local governments to act in a way that aligns with the central government's goals.Footnote 19 In the Chinese context, although many studies have investigated local dibao variations, they have exclusively focused on the urban dibao programme.Footnote 20 The only study that examines the contributing factors and challenges of unifying urban–rural dibao programmes adopted a case-study approach.Footnote 21 The unification of urban and rural dibao programmes (unification policy hereafter) differs from an urban cash-transfer programme in many aspects. First, the unification policy is one of many policy initiatives that aim to promote coordinated development in urban and rural areas and facilitate urbanization in China. Second, it is a social policy that enhances social equity by levelling dibao thresholds in cities and the countryside. Third, it is also a welfare expansion and a poverty alleviation initiative that raises the dibao threshold in rural areas.

Second, our study contributes to the theoretical understanding of how internal and external forces shape social policymaking in developing countries with multilevel governance. We find that internal fiscal constraints and external top-down pressures are the major factors driving dibao unification. In terms of fiscal constraints, we show that the existing cost of social expenditure, instead of local fiscal conditions such as capacity or dependency, affects the decision to implement a unification policy. For top-down pressure, existing studies overlook the heterogeneous roles that different types of directives play in facilitating social policy diffusion.Footnote 22 We contribute to the literature by distinguishing directives with different coercive powers, finding that only the directives that set specific targets or timetables for policy implementation accelerate adoption.

The Unification of Urban and Rural dibao Programmes

The urban–rural divide in the dibao programme since its establishment

As China's primary social-assistance programme, dibao provides a cash transfer to households with incomes below a locally specified threshold. In 2019, it covered 43.21 million people, 8.61 million of whom were from urban areas (1.0 per cent of the urban population) and 34.6 million from rural areas (6.3 per cent of the rural population).Footnote 23 Dibao was initially a pilot programme launched by the Shanghai government in 1993; it was then rolled out to all cities in 1999. Once established in urban areas, local governments began experimenting with similar programmes in rural areas, managing complete coverage by 2007.

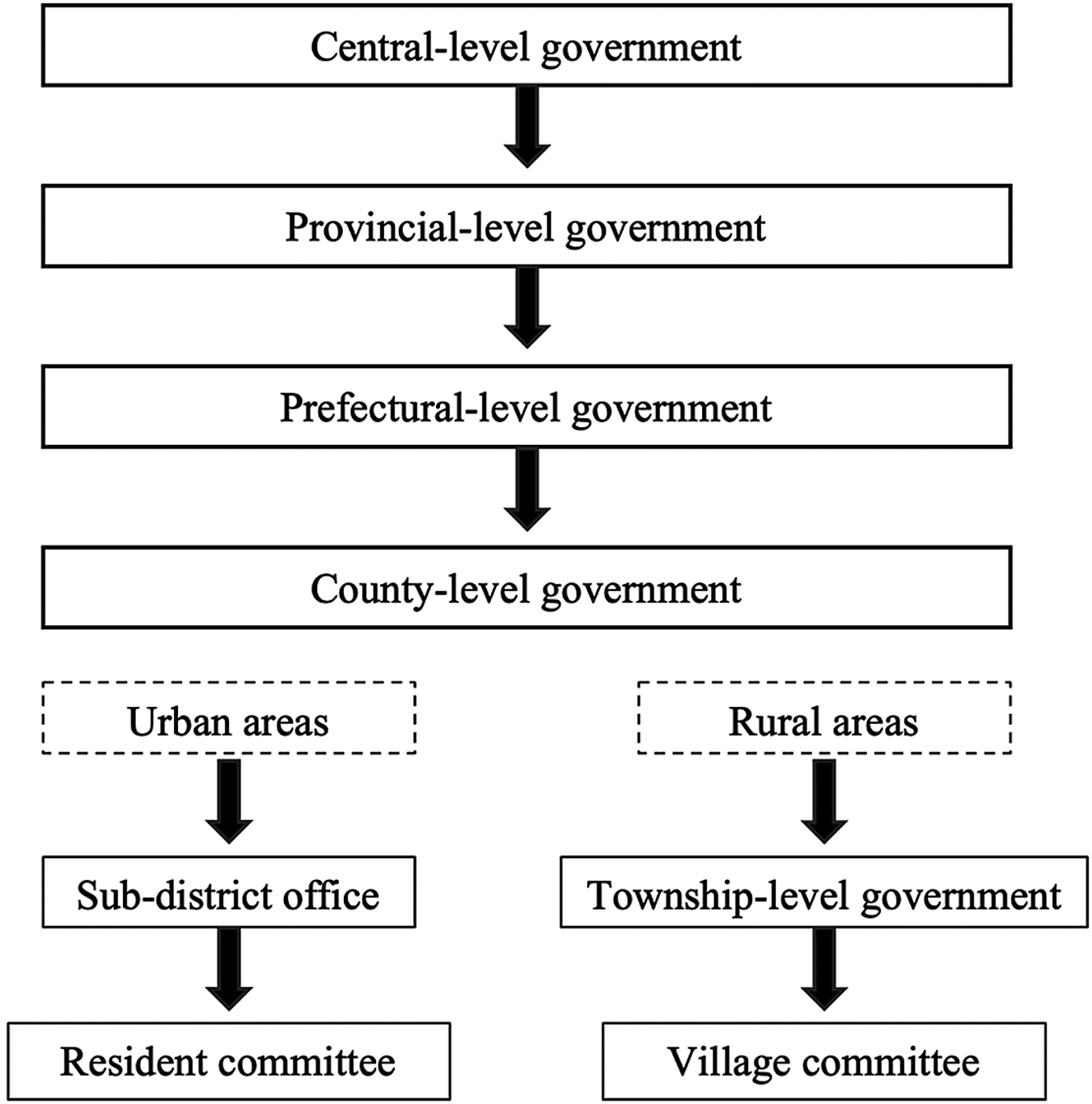

The dibao programme is decentralized (see Figure 1). In general, China's administrative system comprises five hierarchical levels: central, provincial, prefectural, county and township governments, or a sub-district office. The State Council promulgates dibao regulations that outline the general principles. Provincial and prefectural governments issue measures for implementation, which are then adapted to local conditions. In practice, governments at the county level and below, along with the civil affairs bureau (CAB), implement the programmes and decide on eligibility thresholds and beneficiaries.

Figure 1. Administrative System in China

Urban and rural dibao programmes differ initially in their eligibility thresholds. According to the national regulations on dibao, local governments (county level and above) have the discretion to set the eligibility thresholds according to the local cost of living.Footnote 24 The higher cost of living in cities means that urban dibao thresholds are persistently higher than those in rural areas. In 2007, the average threshold was 82.3 yuan per month in rural areas, less than half (45.1 per cent) of that in urban areas (182.4 yuan). That gap has narrowed over the years: in 2019, the average rural threshold was 444.6 yuan per month, which is 71.3 per cent of the urban threshold (624.0 yuan per month).Footnote 25

The dibao programmes also differ in their application and screening procedures, particularly in the levels of discretion used by “street-level bureaucrats” in approving dibao applications. Generally, residents apply for dibao via community-level self-governance organizations (shequzizhi 社区自治) – residents’ committees in cities and village committees in the countryside. The frontline staff of these committees conduct a preliminary investigation into each applicant's household conditions and then convene a participatory appraisal to certify eligibility. Staff then submit qualifying applications to a subdistrict office (in cities) or township-level government (in the countryside) for further review. The CAB of a county-level government has final approval (see Figure 1). According to national regulations, households whose incomes fall below the threshold are eligible for dibao.Footnote 26 Provincial and prefectural-level regulations further specify the definition and calculation of household income and other eligibility criteria (for example, the amount of living space and possession of luxury goods) based on local conditions.

Although eligibility rules are stipulated in the regulations, in practice the allocation of welfare resources is affected by the decisions made by individual officials. In cities, despite a certain level of discretion, frontline staff are generally subject to a checks-and-balance system, as “street-level bureaucrats” in residents' committees are required to conduct procedures such as household surveys and neighbourhood visits when reviewing an applicant's eligibility.Footnote 27 Rural areas lack a well-functioning checks-and-balance mechanism, and owing to the difficulty of assessing household income in the countryside and limited administration resources, village leaders have considerable discretion when allocating welfare resources. Prior studies have found that village leaders tend to allocate dibao benefits according to personal relationships, such as kin networks or other, political ties, rather than based on public need or cost-of-living thresholds.Footnote 28

National directive to integrate the urban and rural dibao programmes

In line with its agenda to coordinate urban and rural development, the central government has since 2010 demonstrated an interest in combining rural and urban dibao programmes into a unified programme with the same eligibility criteria and administrative procedures. In 2011, the State Council issued its “Guidelines on formulating and adjusting the thresholds of dibao for rural and urban residents” (2011 Guideline hereafter). The 2011 Guideline required local governments to gradually narrow the gap between urban and rural dibao thresholds and encouraged localities to adopt a standard threshold. In 2012, the State Council issued its “Opinions on further strengthening and enhancing dibao implementation” (2012 Opinions hereafter), which outlined the principles and measures required to improve the implementation of dibao for both urban and rural residents.

Building on the 2011 Guideline and 2012 Opinions, the State Council promulgated the “Provisional regulations on social assistance” (2014 Regulation hereafter) in an attempt to gradually eliminate the urban–rural difference.Footnote 29 The 2014 Regulation provided a unified framework for urban and rural dibao programmes and introduced two major changes. First, prefecture-level governments (and above) – instead of county-level governments – would now be responsible for formulating the dibao threshold. This would allow prefecture-level governments to set a roadmap towards a unified dibao threshold. The second change allowed applicants to submit applications directly to their township-level government (a subdistrict office in cities and township government in the countryside), rather than go through the preliminary screening process previously administered by residents' or village committees. This change reduced the arbitrary power of “street-level bureaucrats” when approving dibao applications and facilitated the formation of a unified and formalized administrative procedure.

Adoption of an urban–rural unified dibao threshold at the local level

Although the national government has encouraged local governments to adopt a standardized dibao eligibility threshold, this has not been mandated and is only a “recommended” policy for localities. Therefore, local governments can decide whether to opt in. In this study, we chose prefectural-level governments as the unit of analysis because they are the most important subnational governments in charge of formulating the dibao thresholds.

The speed of adopting unified thresholds has been rather slow. By the end of 2019, only 61 (18 per cent) prefectural-level divisions had adopted a unified urban–rural dibao threshold. Of those, 41 had adopted a within-prefecture unified threshold – that is, the same threshold is applied for the whole prefecture. Furthermore, 20 had adopted a within-county/district-level unified threshold, whereby dibao thresholds in urban and rural areas are unified but differences across counties or districts remain.

The Central–Local Relationship and Policymaking in China

Central–local relations are fundamental institutional arrangements that shape policymaking in China. The first feature of this relationship is the centralization of organizational structure and the decentralization of economic policies. Central or superior governments retain tight control over the appointment, promotion and dismissal of cadres through the CES.Footnote 30 This appraisal is largely dependent on hitting “hard targets,” such as GDP growth and revenue generation, whereas “soft targets,” such as social development, are considered less important.Footnote 31 Although the administrative and personnel systems are highly centralized, local governments are intentionally granted autonomy in economic policies for innovative experimentation. This achievement-oriented appraisal system and the decentralization of economic policy encourage regional competition to stimulate economic growth.Footnote 32

The second feature is fiscal imbalance, which is characterized by a highly centralized fiscal authority and decentralized fiscal responsibility.Footnote 33 In 1994, China implemented a tax reform to recentralize revenue and decentralize expenditure. Local governments now have to bear the burden of the majority of daily administration and social service expenses while the share of tax revenue that they can retain has decreased.Footnote 34 The imbalance has intensified fiscal pressure on local governments and, in order to meet their responsibilities, they have to seek extra-budgetary revenue.Footnote 35 Since fiscal expenditure is decentralized and CES is largely GDP-oriented, local governments are more incentivized to invest in infrastructure projects, which can easily demonstrate their achievements to their superiors,Footnote 36 and less inclined to invest in social services, which are considered to be costly and counterproductive.Footnote 37

The central government sought to alleviate the intensified fiscal stress on local governments caused by the 1994 reform by gradually introducing fiscal transfers to localities in less-developed regions. Local governments that relied more on fiscal transfers to cover their expenditure had higher levels of fiscal dependency because they had fewer economic resources at their disposal and were more fiscally constrained by the central and superior governments.Footnote 38

To sum up, conditioning politicians’ career promotion on economic development and revenue generation stimulates local officials’ pursuit of GDP growth. Such enthusiasm for GDP is further intensified in a fiscal system with a highly centralized fiscal authority and decentralized responsibility.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

A constellation of factors affects policy adoption, including internal features, top-down pressure and a horizontal diffusion mechanism.Footnote 39 This section reviews the literature on how these factors affect policy diffusion in China and establishes hypotheses for the dibao unification policy.

Internal features

The existing literature suggests that fiscal factors, such as the cost of providing services and local fiscal conditions, are crucial determinants of redistributive policies.Footnote 40 Adoption of a unified dibao threshold has been voluntary; central and provincial-level governments did not make any financial arrangements to support the increased expenditure. Local governments have to cover the additional cost. Therefore, fiscal factors, such as the financial cost of unifying urban–rural dibao thresholds and the localities’ general fiscal conditions, are crucial in a local government's unification decision.

As unification involves raising the rural dibao threshold to an urban level, localities that initially had a larger number of dibao recipients or a wider urban–rural threshold gap would incur larger direct costs for unification. Besides the direct costs, unification of dibao thresholds could also lead to a surge in expenditure on other social welfare programmes linked with dibao thresholds (for example, disability allowance or benefits for farmers who have lost their land). Hence, localities with a higher social expenditure burden would be impacted more by the direct and indirect costs incurred from dibao unification. We hypothesize that localities facing greater direct costs or a higher social expenditure burden from unification are less likely to adopt a unified dibao threshold (H1.1).

The general fiscal conditions of localities also impact the adoption of a unification policy. Fiscal capacity reflects a fiscal system's extractive capability to raise tax revenues.Footnote 41 Policy diffusion literature in China suggests that fiscal capacity affects the adoption of policy innovation, such as a housing adaptation policy for older adultsFootnote 42 and a “one visit at most” policy that aims to improve administrative efficiency.Footnote 43 As the unification of dibao thresholds is resource consuming, localities with greater fiscal capacity are more likely to be able to afford the reform. Localities with lower fiscal capacity are less likely to adopt a policy that would further deteriorate their fiscal condition. Hence, we hypothesize that localities with greater fiscal capacity are more likely to adopt a unified dibao threshold (H1.2).

Besides fiscal capability, fiscal dependency is another factor affecting policy adoption. Local governments that are less financially independent usually compete with each other for transfers from superior governments. To show their loyalty to superior governments and stand out in the race for fiscal transfers, localities that are more financially dependent tend to adopt new social welfare policies that demonstrate innovation.Footnote 44 Xufeng Zhu and Hui Zhao's study found that when establishing a dibao programme was still voluntary, cities with higher fiscal dependency were more likely than their counterparts with lower fiscal dependency to implement the policy.Footnote 45 Therefore, we hypothesize that localities with higher fiscal dependency are more inclined to unify the dibao thresholds (H1.3).

Top-down pressures

Superior governments can accelerate the adoption of new policies through a variety of tools, including mandatory measures (for example, administrative regulations), financial incentives (for example, matching funds) and the dissemination of relevant policy information (for example, best practices).Footnote 46 In China, the hierarchical administrative system and tight control over cadre promotion ensure local compliance with top-down mandates. The 2011 Guideline promulgated by the State Council encouraged localities to adopt a unified urban–rural threshold. Provincial governments, serving as the intermediary agents between the central and local government (prefecture-level and below), reacted differently to the central government's principle based on local circumstances. Two types of directives with varying levels of coercion were issued. Directives with lower coercive power encouraged the localities to unify the thresholds in urban and rural areas, where conditions allowed. Directives with higher coercive power set specific targets or timetables by which thresholds were to be unified. Prior studies investigating social policy diffusion show that directives from provincial-level governments accelerate the diffusion of the urban dibao system,Footnote 47 the unified urban–rural health insuranceFootnote 48 and the housing adaptation policy.Footnote 49 Therefore, we hypothesize that when a provincial-level government has issued a directive to unify urban–rural dibao thresholds, its subordinate prefecture-level governments will be more likely to adopt the policy (H2.1). Moreover, the issue of different types of directives allows us to further examine the differential effects of a directive with varying coercive powers. We assume that the relationship between the issuing of a provincial directive and the adoption of the unification policy is stronger for directives with higher coercive power (H2.2).

Horizontal diffusion mechanism

Besides top-down pressure from a superior government, a government's policy choices are also influenced by those made by its neighbouring jurisdictions. Previous studies suggest two mechanisms of policy diffusion: learning and competition.Footnote 50 Local governments learn from their neighbours and borrow innovations they perceive to be successful at resolving similar social and economic problems. Local governments also compete with neighbouring jurisdictions for resources and opportunities. Local officials come under pressure to keep up with their peers in neighbouring governments, because failure to implement a successful policy that has been adopted by their peers can impede their own career advancement. In China, the highly centralized administrative and personnel systems create a “promotion tournament” for local officials, and competition has been suggested as the main mechanism for horizontal diffusion.Footnote 51 As local leaders within a jurisdiction tend to be evaluated and appointed by the same superior government,Footnote 52 competition mainly occurs between cities within the same province.Footnote 53 The “race to the top” in economic policy among cities within the same province is well documented.Footnote 54 For example, Zhu and Zhang find that a city's likelihood of adopting pro-business administrative reform is positively associated with the percentage of other cities within the same province adopting the reform.Footnote 55

Some studies on social welfare policy, however, raise the issue of “racing to the bottom.”Footnote 56 The proposition is that poor people may migrate across localities to receive better welfare benefits. Afraid of becoming “welfare magnets,” local governments then compete to be less attractive to poor people. But other studies conducted in China have revealed a “race to the top” competition in social welfare programmes. For example, an increase in the share of cities within the same province that adopted urban dibao programmes increased the probability that other cities would adopt one, too.Footnote 57 A similar phenomenon was also found for the integration of urban–rural medical insuranceFootnote 58 and housing adaptation policy for the elderly.Footnote 59 The phenomenon of “racing to the top” in social policy in China can be seen as a strategy used by local officials to win a political tournament. While economic development and revenue-making are still “hard targets” in the CES, social policy is gaining prominence. Failure to perform satisfactorily on social welfare programmes may leave a negative impression on superior governments.Footnote 60 Therefore, we hypothesize that a locality's adoption of a unified urban–rural dibao threshold is positively associated with adoption by its neighbours (H3).

Method

Data

We constructed a panel policy dataset on the annual timing of the adoption of unified urban–rural dibao thresholds in 336 prefecture-level administrative divisions in China between 2011 and 2019.Footnote 61 We set 2011 as the starting point because this was when the central government started to encourage the unification of urban–rural dibao thresholds.

In 2020, we drew data on the timing of adoption primarily from the dibao thresholds announced by the CAB in each prefecture-level division. To supplement and cross-validate the adoption information, we also used sources such as the county-level dibao thresholds compiled by the MCA from 2011 to 2017 as well as news articles.Footnote 62 We then merged the policy data with other data sources to construct explanatory and control variables. The panel dataset on the timing of policy adoption and prefecture-level characteristics covered 293 prefecture-level cities. Our final analytic sample contained 240 cities which did not have missing information for the explanatory and control variables.Footnote 63

Measure

Table A2 (in the supplementary material) presents the description and data source of each variable. The explanatory variables capture three aspects: internal fiscal factors, top-down pressure and horizontal competition. We also controlled for urban–rural integration level and economic, political and demographic characteristics. Most variables are time-variant variables from 2010 to 2018. We lagged their values by one year to ensure that the prediction of adoption at year t was based on the characteristics at year t – 1. Some variables were time-invariant values in 2010 because of the need to control for conditions prior to policy changes or because data were only available in the 2010 census.

The fiscal factors included the costs of unifying urban–rural dibao thresholds, social expenditure burden, fiscal capacity and fiscal dependency. The costs were measured by two variables: initial gaps between urban and rural dibao thresholds – that is, the ratio between urban and rural thresholds in 2010 – and the number of rural dibao recipients – i.e. the total number in 2010. Social expenditure burden was measured by the ratio between social expenditures (for social security and employment) and budgetary fiscal expenditures from 2010 to 2018. The higher the ratio, the higher the burden. We constructed two variables to measure fiscal conditions: fiscal capacity and fiscal dependency. Capacity is the ratio between fiscal revenue and GDP from 2010 to 2018; dependency is the difference between fiscal expenditures and revenue divided by expenditures from 2010 to 2018.Footnote 64

To capture the top-down pressure, we constructed two variables for provincial directives with lower and higher levels of coercive powers. The first variable documented whether the provincial government had issued a directive encouraging the unification of urban and rural dibao thresholds. The second variable documented whether the provincial government had issued a directive setting specific targets or a timetable for narrowing or unifying the thresholds. To construct this variable, we collected all social assistance-related directives, including dibao regulations and social-assistance laws promulgated by each province from 2010 to 2018.

To capture the horizontal competition, we constructed two variables to measure both the general and specific competition. General competition was measured by the proportion of cities in the same province that had adopted the unification policy in a given year. Such a measure has been widely adopted in policy diffusion studies in China.Footnote 65 As the performance appraisal system was primarily based on economic growth, cities with similar levels of economic development were more likely to treat each other as potential competitors.Footnote 66 We then created another variable, specific competition, to capture the competition among economic neighbours. Specific competition was measured by whether the city's economic neighbour had adopted the unification policy in a given year. Specifically, for city i, its economic neighbour is a city in the same province whose within-province ranking of GDP per capita is one place above that of city i. If city i is ranked first, then its economic neighbour is the one whose ranking is one place below that of city i.

The control variables measuring the level urban–rural integration included the urbanization rate and urban–rural income gap. The economic characteristics included economic growth and the level of economic development. Political factors were captured by the tenures of both mayors and Party secretaries to accommodate their potentially different responses to CES.Footnote 67 Previous research reports that the average tenure of municipal mayors and Party secretaries between 2000 and 2010 was 3.2 and 3.6 years, respectively.Footnote 68 Hence, if the mayors or Party secretaries had been appointed within three years before the end of a given year, they were regarded as being in the early stage of their tenure. The demographic characteristics included population, ethnicity, age dependency level, education level and region. Urban–rural integration level, level of economic development and demographic characteristics were all time-invariant variables in 2010.

Empirical strategy

We employed event-history analysis to examine the factors that influenced the timing of when unified urban–rural dibao thresholds were adopted. The analysis of this study began in 2011 and ended in 2019. Time was measured in discrete units as the number of years since 2011 (t) until a city (i) adopted a unification policy. Cities that had adopted the policy prior to 2011 were not included in the analysis. Data were arranged in a city–year format. The individual city had a row for every year beginning with 2011 up until the year when the city adopted the unification policy. There are two important distributional functions: the survival function and the hazard function. The survival function indicates the probability that a city had not yet adopted the unification policy by time t; the hazard function is the probability that a city adopted the unification policy during any given time point t.

Among the models used in event-history analysis, we employed Cox's proportional hazard model. The Cox model is a semi-parametric model that estimates how the hazard function changes as a function of the covariates, without making assumptions on the distribution of the hazard function.Footnote 69 Because cities are clustered in provinces, we incorporated random effects, also called a frailty model, to account for within-province homogeneity in outcomes.Footnote 70 The Cox's proportional hazard model relates explanatory variables to the hazard function:

where hi (t) is the hazard of adopting the unification policy in city i on year t, h0 (t) is the unspecified baseline hazard, xi 1 is the time-invariant covariate for city i, xi 2 is the time-variant covariate for city i in year t − 1, and β is a k × 1 vector of coefficients, where k is the number of covariates. αj denotes the random effect associated with the jth cluster (province).

Empirical Results

Descriptive statistics

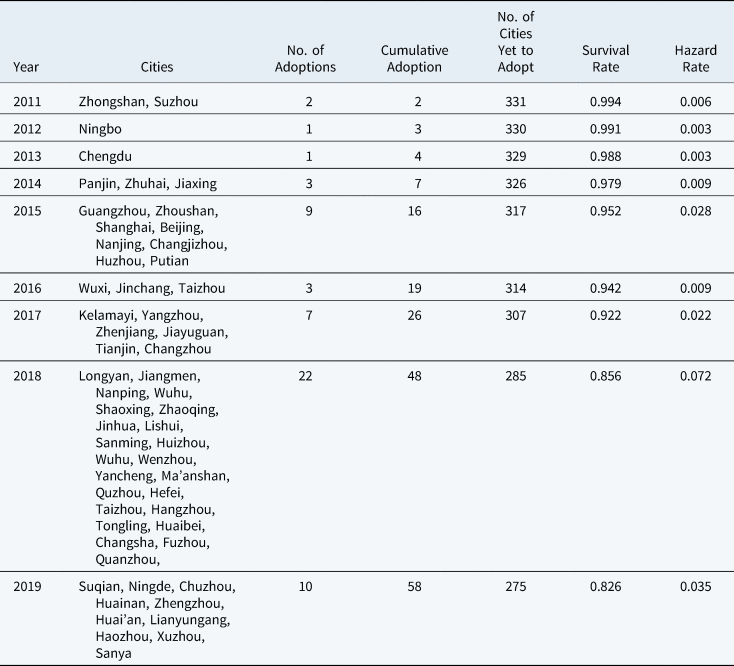

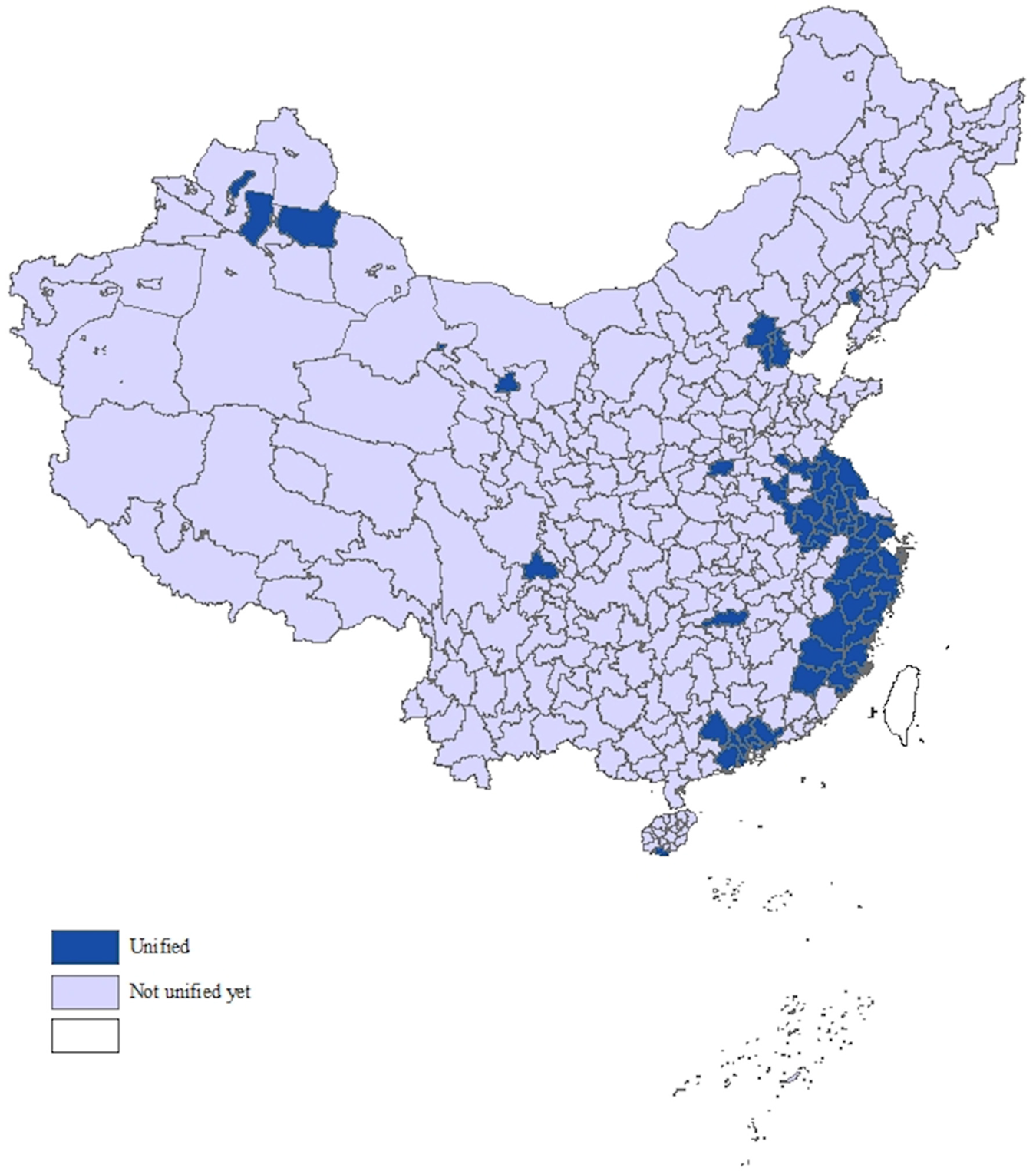

Table 1 presents the number of cities that adopted the unification policy each year, the survival rate and the hazard rate. Three cities (Shenzhen in 2005, Foshan in 2007 and Dongguan in 2008) unified their urban–rural dibao thresholds before 2011 and therefore were not included. By the end of 2019, 17.4 per cent of the cities (58 out of 333) unified their urban–rural dibao thresholds. As indicated by the survival rate, the unification policy spread slowly from 2011 to 2019. For example, the survival rate was 0.922 in 2017, indicating a probability of 92.2 per cent that a city had not yet adopted a unification policy by 2017. The hazard rates from 2011 to 2014 were all less than 1 per cent, indicating that less than 1 per cent of the cities adopted a unification policy in that year. It increased to 2.8 per cent in 2015 after the issuance of the 2014 Regulation. In 2018 and 2019, the hazard rate reached 7.2 per cent and 3.5 per cent, respectively. Figure 2 further illustrates the adoption pattern by providing the spatial distribution of the unification policy by the end of 2019. Three-quarters of the unified cities were located in eastern regions – in Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Guangdong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Hainan, Hebei and Liaoning. The rest of the cities were dispersed in central and western provinces such as Anhui, Xinjiang, Henan, Hunan, Sichuan and Gansu.

Table 1. Cities Adopting a Unified Urban–Rural dibao Threshold, Survival Rate and Hazard Rate, by Year

Figure 2. Spatial Distribution of Cities Adopting Unified Urban–Rural dibao Threshold, 2019

Table A3 (in the supplementary material) provides the summary statistics for the provincial directives on the unification policy. Panel A shows that among the 27 provincial-level divisions, nine of them issued the provincial directive with lower coercive power.Footnote 71 Five provinces issued the provincial directive with higher coercive power. The spatial distributions of provincial directives with lower and higher coercive power by the end of 2019 are illustrated in Figure A1 (in the supplementary material). The descriptive statistics for the other explanatory and control variables are presented in Table A4 (in the supplementary material).

Regression results

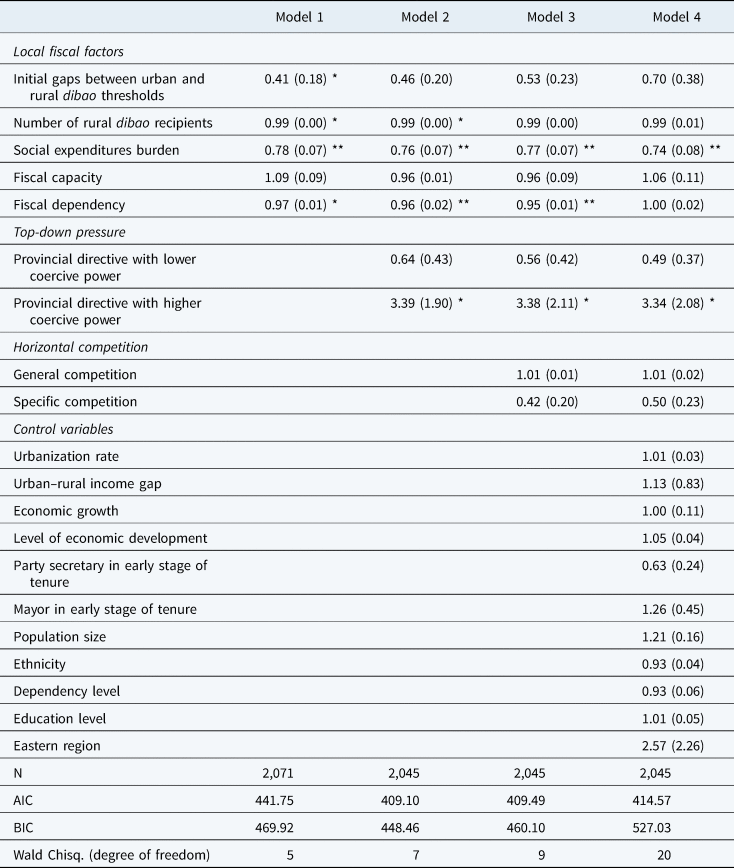

Table 2 presents the results of the Cox proportional hazard models. Our modelling approach started with the minimally specified model, which only included internal fiscal factors (Model 1). Subsequently, variables measuring top-down pressure (Model 2) and horizontal competition (Model 3) as well as the control variables (Model 4) were added to the model. Hazard ratios (HRs) are reported. An HR greater than 1 signifies higher probability of policy adoption, whereas an HR less than 1 indicates lower probability.

Table 2. Cox Proportional Hazard Models Predicting the Unification Policy

Notes: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01. AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion

Model 1 shows that higher initial gaps between urban and rural dibao thresholds, larger counts of rural dibao recipients and higher social expenditures reduced the probability of unifying urban–rural dibao thresholds (HR = 0.41, p < 0.05; HR = 0.99, p < 0.05; HR = 0.78, p < 0.01). Higher fiscal dependency also reduced the probability (HR = 0.97, p < 0.01). Model 2 added the variables on top-down pressure. A provincial directive with lower coercive power was not significantly associated with the probability of adopting a unification policy, whereas a provincial directive with higher coercive power significantly increased the probability (HR = 3.39, p < 0.05). The association between the initial urban–rural benefit gap and policy adoption became insignificant. Model 3 added the horizontal-competition variables. Neither general nor specific competition was associated significantly with the adoption of a unification policy. The association between the number of rural dibao recipients and the adoption of a unification policy became insignificant. Model 4 showed that, after adding the control variables, the burden of higher social expenditures significantly reduced the probability of policy adoption (HR = 0.74, p < 0.01), whereas provincial directives with higher coercive power increased the probability (HR = 3.34, p < 0.05). The significant association between fiscal dependency and policy adoption became insignificant. None of the control variables was statistically associated with the adoption of a unification policy.

Discussion

This study examines the forces driving local governments’ adoption of a dibao unification policy aimed at coordinating urban–rural development, improving social equity and expanding social welfare. This topic is especially important given that many developing countries are on a similar trajectory to ameliorate urban–rural inequality and to pursue equity in development. Through event-history analysis on the timing of unification in Chinese prefecture-level divisions from 2011 to 2019, we found that local adoption of a unified dibao threshold was primarily shaped by internal fiscal constraints and top-down directives with higher levels of coercive power; however, horizontal competition between cities exerted no influence over policy adoption. Our findings shed light on facilitators and obstacles behind decentralized policymaking in the context of promoting urban–rural integration in developing countries.

Regarding internal fiscal factors, the existing costs of social expenditures (H1.1 partially supported) – instead of local fiscal conditions such as fiscal capacity or dependency – affected the policy decision (H1.2 and H1.3 not supported). This finding echoes the case study by Yuebin Xu and Lu Yu in which they interviewed local policymakers and found that financial affordability was a leading contributing factor and a major challenge for the unification of urban–rural dibao thresholds.Footnote 72 Prior studies conducted in other developing countries also show that the inadequacy of financial resources contributed to poor service delivery outcomes at the local level.Footnote 73 Under the current fiscal system, in which fiscal responsibilities are pushed down level by level from higher-level governments to the lower ones,Footnote 74 it is unsurprising that local governments (at the prefectural level and below) are reluctant to adopt policies voluntarily for which they must pay incurred costs out of their own pockets. In summary, we find that fiscal affordability constrains local governments from expanding social welfare and bringing social equity to rural areas. If the higher-level governments aim to accelerate the unification process, they should arrange fiscal transfers to make policy adoption more affordable.

Top-down pressure exerts a strong influence on a local government's decision to unify dibao thresholds in urban and rural areas (H2.1 supported). The positive effect of vertical command on local policymaking manifests in other countries with multilevel governance, such as Indonesia.Footnote 75 Moreover, we found that only provincial directives with higher levels of coercive power have a significant impact (H2.2 supported). Such directives are highly paternalistic in nature and specify detailed targets and timetables, allowing little discretion for local governments.Footnote 76 They also send a strong signal to local governments regarding the provincial government's desire to achieve the unification objective. In a multilevel government, in which superior governments retain tight control over the career mobility of local officials, such directives not only demand local compliance but also create internal incentives and motivations for local officials to comply.

Prior studies have found evidence of a “race to the top” for social policy in China.Footnote 77 Our results, however, show neither a “race to the top” nor a “race to the bottom” in the adoption of a unification policy (H3 not supported). In our study, the non-significant effect can be attributed to the dibao unification policy offering little political reward: “Many local officials do not try to learn from other experiments but want to take credit for being innovative.”Footnote 78 Although soft targets, such as enhancing social welfare through expanding social policies, are gaining prominence in the CES, local officials may introduce or amend social policies based on potential rewards, and they may only compete in policies that will help them to gain more credit. The unification of urban–rural dibao thresholds primarily benefits rural dibao recipients, the majority of whom are from extremely marginalized groups. Unification may be perceived as less politically lucrative than other social policies such as the integration of health insurance, which creates long-term investment returns on human capital and involves a larger beneficiary group that is economically productive.Footnote 79 The relatively small political rewards to be gained from the unification of thresholds may also explain why policy adoption was low, in contrast to the rapid diffusion when dibao was first established in cities.Footnote 80 When established in the 1990s, urban dibao was not only a social welfare programme but also a political tool to pacify workers laid-off from state-owned enterprises and maintain social stability. The prioritized status of social stability in the CES accounted for much of the rapid local adoption in the 1990s, while the linkages between unification policy adoption and advantages in the CES have been more opaque.

A dibao unification policy carrying little political reward in the CES also explains why provincial directives with less coercive power exerted an insignificant effect on the policy adoption rate. This type of voluntary directive is cooperative in nature in that policy goals are articulated and compliance is encouraged, but local governments are granted discretion over whether and when to unify.Footnote 81 Since the chances of political gain are slim in adopting such a policy, local officials’ motivation to implement it is low, so long as the directive has less coercive power. In summary, although social policy generally has an elevated status in the political agenda, it does not change the fact that local officials will only compete for policies that will win them more political rewards. For social policies that are perceived as being less politically rewarding, our findings suggest that a top-down directive with higher coercive power can accelerate diffusion.

This study is not without limitations. First, while the integration of urban and rural dibao programmes includes adopting both a unified threshold and the same administrative procedures, this study only captures the former aspect. Second, the unification of urban and rural dibao programmes is still an ongoing process; relying on data collected only up until 2019 can only provide a partial picture from early adopters. Despite the limitations, this study has implications for implementing social policy in developing countries with multilevel governance. First, we find that financial constraints are the main obstacle to the local adoption of poverty-alleviation programmes. Second, top-down directives with higher coercive power are potent tools to accelerate the adoption of poverty-alleviation programmes that otherwise would have less appeal to local officials. Third, in the current CES, dibao unification is not politically lucrative, thus there is no horizontal competition.

We suggest that two policy tools could be used to facilitate the diffusion of dibao unification policy. First, fiscal transfers from superior governments to local governments could overcome the unaffordability of policy reform. Second, adding an assessment of dibao unification to the CES would incentivize local officials to implement the policy. Both policy tools are used in China's Targeted Poverty Alleviation Programme and have been found to contribute to its success.Footnote 82 The findings from this study can inform the government on how to facilitate the diffusion of social policy in the context of a decentralized social policy system and social policy innovation.Footnote 83 Future studies could apply the theoretical framework developed in this study in other developing countries with decentralized poverty-alleviation programmes to facilitate the theorization of policy-adoption facilitators across various geographic contexts.

Supplementary material

The appendices are available online as supplementary material at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741023001030.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the funding support of the Contemporary China Research Cluster Postdoctoral Fellow Scheme of the Faculty of Social Sciences, the University of Hong Kong.

Competing interests

None.

Chenhong PENG is an assistant professor at the department of social work and social administration, the University of Hong Kong. Her research interests cover social policy (social protection policy, housing policy and old-age income protection policy) and poverty alleviation. Her work has been published in The China Quarterly, Journal of Social Policy, Social Science and Medicine and Health Policy and Planning.

Julia Shu-Huah WANG is an associate professor at the department of social work, National Taiwan University, and an honorary associate professor at the department of social work and social administration, the University of Hong Kong. Her research focuses on social welfare policies, immigration policies and the well-being of families. She is currently investigating the design and impacts of social safety nets in East Asia and beyond as well as the patterns and effects of hukou reforms in mainland China.