The OECD’s involvement with climate finance dates back to the 1990s and thus much further than that of the other international economic institutions. The OECD as an institution involves a wider range of actors, particularly domestic ministries, than the other two institutions, as exemplified by the involvement of development ministries in the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC). While it is still essentially an economic institution with the objective of improving the economic and social wellbeing of people around the world and with its economic worldview (Reference RuffingRuffing, 2010), it has addressed non-economic policy issues such as development and environmental protection to a larger degree than the other two institutions. Compared to them, its membership circle is much more restricted to developed countries, so much so that OECD membership has become synonymous with being a developed country.

As a knowledge-producing institution, the OECD has produced numerous reports and other publications on climate finance, which can be divided into two strands: a development strand within which the DAC has published statistics on the provision of development aid with climate objectives and an investment strand producing analyses of how to redirect investment to green purposes. This chapter outlines these two strands, and proceeds to analyse the factors that shaped them (institutional interaction, worldview and member states). Finally, the chapter discusses the consequences of OECD output for the international (especially the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change [UNFCCC]) and domestic levels (most salient regarding the development strand).

11.1 Output: The Investment and Development Strands

The OECD has addressed climate finance since the 1990s. Notably, in 1998 the DAC introduced the so-called Rio Markers for reporting aid projects related to biodiversity, desertification and climate change mitigation. In 2007, Rio Marker reporting became mandatory for member states and an adaptation marker became mandatory in 2010. The OECD involvement with climate finance can be divided into two strands: one based on the OECD’s established expertise regarding development aid and one based more on its expertise on investment. Within both of these, formal OECD output is knowledge based, and includes both formal (numerous reports, climate finance statistics and reporting with the DAC as well as panel discussions) and informal (workshops and seminars) types.

In the development strand, the DAC monitors and provides statistics on the Official Development Aid (ODA) of member states based on reviews of their reports, and consists of representatives of the member states (mainly development and foreign ministries) as well as of OECD staff, particularly from the Development Co-operation Directorate. Not all OECD members are DAC members. At the time of writing, Chile, Colombia, Estonia, Israel, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico and Turkey were OECD but not DAC members. Subsidiary bodies under the DAC such as the Network on Environment and Development Co-operation discuss issues relating to environmental protection and development aid, particularly issues concerning tracking development aid with an environmental objective and the difficulties with such tracking. The meetings of the DAC and its subsidiary bodies mainly serve to develop and disseminate knowledge, including best practices.

Concerning the cognitive issue of defining climate finance, the development strand has framed climate finance primarily as a subtype of development finance, and bilateral climate finance as a subtype of ODA. Given that the OECD does not address the issue of whether climate finance is new and additional to development aid, and the countries’ reporting of their climate finance is very prone to over-coding (Reference Michaelowa and MichaelowaMichaelowa and Michaelowa, 2011a), the OECD figures of bilateral climate finance have been criticised for being too high (Reference Roberts and WeikmansRoberts and Weikmans, 2017). This is true concerning figures for individual countries as well as for the OECD estimates of total amounts of climate finance provided by the OECD countries. Developed countries often base their individual biannual climate finance reports to the UNFCCC on the data reported to the DAC, and these reports have often been criticised for exaggerating the amounts provided, particularly regarding adaptation (Reference Donner, Kandlikar and WebberDonner et al., 2016; Reference Roberts and WeikmansRoberts and Weikmans, 2017; Reference Weikmans, Roberts, Baum, Bustos and DurandWeikmans et al., 2017). The OECD has cautioned that its DAC figures were intended to provide descriptive statistics to track the mainstreaming of the objectives of the MEAs adopted at the Rio Convention, not to measure progress concerning pledges or to compare countries (OECD, 2012a, 2018a; Reference Weikmans and RobertsWeikmans and Roberts, 2018).

As a key example of the estimates of total flows, the OECD and the Climate Policy Initiative (2015a) estimated that total climate finance in 2014 amounted to USD 61.8 billion. Of this total, public climate finance amounted to USD 43.5 billion, and public bilateral climate finance to USD 23.1 billion, consisting mainly of climate-related ODA reported to the UNFCCC but also of ‘Other Official Flows’ (public finance not classified as ODA because it is not primarily aimed at development or because the grant component is less than 25 per cent). The OECD was tasked with providing this report by the Presidencies of UNFCCC Twentieth and Twenty-first Conference of the Parties (COP20 and 21, Peru and France) in order to provide an up-to-date aggregate estimate of mobilised climate finance and an indication of the progress made towards the UNFCCC climate finance goal (OECD, 2015a). The report’s finding that the USD 61.8 billion constituted the developed/Annex II countries’ progress towards mobilising the USD 100 billion caused much criticism especially from UNFCCC negotiators from developing countries (Reference SethiSethi, 2015). The negotiators argued that the actual figure was much lower, even as low as USD 2.2 billion USD (Reference DasguptaDasgupta and Climate Finance Unit, 2015). In a 2016 report, the OECD Secretariat projected that public climate finance would reach USD 67 billion by 2020, and argued that the USD 100 billion target being met depended on whether the amount of private finance leveraged per unit of public finance increased from current levels (OECD, 2016).

In terms of generating climate finance and the normative ideas regarding this generation, treating climate finance as a type of development aid meant that the OECD helped maintain the current climate finance system in which developed countries determine their contributions individually. Thus, developed countries de facto determine how much they should provide individually and consequently also in total, and there is little scope for individual or collective targets for public climate finance. Although the OECD did not explicitly endorse this system, it participated in constructing it. The ‘climate finance as ODA’ framing was particularly pronounced in reports from the DAC and the Development Co-operation Directorate (but also involved other Directorates, especially the Environment Directorate) and reflected the preferences of the member states. In this respect, the OECD’s avoidance of assessing whether climate finance was new and additional, both in the reports from the DAC and the OECD Secretariat’s estimate of overall climate finance, is an example of output reflecting such preferences (Reference Weikmans and RobertsWeikmans and Roberts, 2018). It also de facto framed development aid as a source of climate finance and implicitly defined the norm of new and additional climate finance as peripheral to the generation and estimates of climate finance.

The second strand – the ‘investment strand’ – frames climate finance as an instrument in the transition to low-carbon societies and as a way of redirecting investments from ‘brown’ to ‘green’ (Reference Kaminker, Kawanishi, Stewart, Caldecott and HowarthKaminker et al., 2013; Reference Kato, Ellis and ClappKato et al., 2014b; OECD et al., 2018; OECD Secretariat, 2013) and thus does not focus on the size of individual or combined climate finance contributions. The strand is based mainly in the Environment (particularly the Climate Change Expert Group) and the Financial and Enterprise Affairs Directorates. These directorates work closely with the environment and the finance and economics ministries in the member states respectively. Importantly, this strand links climate finance to two key climate issues for the OECD, viz. fossil fuel subsidy reform and carbon pricing (Reference Corfee-Morlot, Marchal, Kauffmann, Kennedy, Stewart, Kaminker and AngCorfee-Morlot et al., 2012; Reference Kato, Ellis and ClappKato et al., 2014a), as well as OECD institutional investment policy (OECD Secretariat, 2010b). More recently, and in line with the G20 and the IMF (see Chapters 10 and 12), the OECD has also focused on making financial flows more green or climate friendly (Reference Jachnik, Mirabile and DobrinevskiJachnik et al., 2019; OECD et al., 2018). Fossil fuel subsidy reform, carbon pricing and institutional investment are issues that speak more directly to the powerful OECD directorates that deal with economic issues and to the parts of the OECD governmental constituencies that come from finance and economics ministries. In this way, this is a rather clear-cut case of economisation in terms of the involvement of parts of the OECD Secretariat working solely on economic issues and the link to issues with strong economic dimensions. As mentioned in Chapters 1 and 7, carbon pricing is a textbook (mainstream) environmental economics solution to climate change, while institutional investment is an inherently economic issue. Even if fossil fuel subsidies can be framed in different ways with varying emphasis on their economic aspects, no framing ignores the economic aspects completely (see Chapter 4).

An important institutionalised forum within this strand is the Research Collaborative on Tracking Finance for Climate Action that constitutes a research network of representatives of OECD Directorates (Development Co-operation, Environment, Statistics and Financial and Enterprise Affairs), international and local research institutes and think tanks, multi- and bilateral as well as national development banks, private investors and financial institutions and government representatives (OECD, 2020c). The Research Collaborative organises formal and informal events as well as published publications (Reference Jachnik, Mirabile and DobrinevskiJachnik et al., 2019), focusing on analysing how private finance can be mobilised by public finance and how to track such private finance. In this way, the Research Collaborative has worked to make it possible to include private finance towards the USD 100 billion target, without explicitly saying what its share should be vis-à-vis public finance.

The investment strand has increasingly overlapped with the development strand, especially when the Research Collaborative has analysed how to assess the amounts of private finance mobilised by public finance, and relies heavily on DAC methods for estimating private climate finance directly mobilised by development aid (OECD, 2017). The interaction with finance ministries and institutional investors has allowed the OECD to teach actors not traditionally interested in climate issues about their importance, and generally to ‘push the envelope’ within the scope of the OECD mandate (interview with senior OECD official, 30 April 2015). Thus, this strand has addressed climate finance in a very broad sense, at times also including finance with a negative or no impact on climate change (Reference Jachnik, Mirabile and DobrinevskiJachnik et al., 2019).

On a related note, in 2016 the OECD established its Centre on Green Finance and Investment, which institutionalised many of the OECD efforts in such investment, and which has a strong focus on a ‘green, low-emissions and climate-resilient economy’, thus emphasising climate mitigation and adaptation within wider environmental issues (OECD, 2019a). The Centre also organises the annual Forum on Green Finance and Investment, a key event in the field.

The OECD output in the investment strand originally framed the question of how climate finance should be generated as an issue of addressing climate change as efficiently and effectively as possible. Thus, it highlighted the need for maximising flows, which de facto meant maximising private flows. Normative ideas of equity, such as Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR) and historical responsibility, were rarely mentioned, and only as part of descriptions of the UNFCCC commitments and principles (Reference Corfee-Morlot, Marchal, Kauffmann, Kennedy, Stewart, Kaminker and AngCorfee-Morlot et al., 2012; Reference Jachnik, Mirabile and DobrinevskiJachnik et al., 2019).

Regarding the principles that should determine the allocation of climate finance, the OECD has mainly emphasised efficiency in its publications, devoting most of its attention to how climate finance might be mitigated most effectively at the lowest cost. Private mitigation finance has been heavily emphasised in this respect (OECD, 2014). Equity has been emphasised in relation to securing an even geographical distribution that guarantees different regions and kinds of developing countries (particularly Least Developed Countries, Land-Locked Countries and Small Island Developing States) their share of climate finance (Reference Haščič, Rodríguez, Jachnik, Silva and JohnstoneHaščič et al., 2015). While the Environment and particularly the Financial and Enterprise Affairs Directorates may have been focused predominantly on mitigation (Reference Kato, Ellis and ClappKato et al., 2014a), the Development Co-operation Directorate has paid more or less equal attention to adaptation, especially as regards the development of the adaptation Rio Marker. However, altogether the development strand has de facto supported the climate finance system in which the decisions about the principles that should guide climate finance has been left to developed countries, while the investment strand has pushed in the direction of a more efficient use of finance for mitigation. Efficiency in the latter case implies spending money where investors obtain most value for money, that is, often emerging economies rather than Least Developed Countries or Small Island Developing States.

11.2 Causes

The initial causes of the OECD addressing climate finance (the first aspect of economisation) originated in different places: while its existing (intra-institutional) experience of development has played an important role, member states have also been a key driving factor (interview with senior OECD official, 25 May 2015). During the UNFCCC negotiations, most OECD member states have actively promoted a role for the OECD in monitoring climate finance, whereas most developing countries preferred institutions established in the UNFCCC. Developing countries have feared that the preferences of the OECD would be close to those of its member states and have been in favour of monitoring conducted by institutions in which they were represented such as the Standing Committee on Finance (SCF). Developed states, on the other hand, wanted to involve the OECD, since this would link development aid and climate finance – effectively designating climate finance as a type of development aid – within an institution which they controlled.

Furthermore, institutional interaction has induced the OECD to address climate finance. The OECD has been commissioned by other international institutions – including the G20 – to undertake research on the mobilisation and delivery of climate finance (G20 Study Group on Climate Finance, 2016a; Reference Röttgers, Tandon and KaminkerRöttgers et al., 2018; World Bank Group et al., 2011). In the run-up to COP21, the Presidencies of COP20 and 21 (Peru and France) also tasked the OECD with providing an up-to-date aggregate estimate of mobilised climate finance and an indication of the progress made towards the USD 100 billion target. Through more indirect pathways, the UNFCCC process – both in preparation for COP21 and the efforts to implement the resulting Paris Agreement – also induced the OECD Secretariat to produce a range of reports and events on their own initiative (e.g. Reference Jachnik, Mirabile and DobrinevskiJachnik et al., 2019; Reference Kato, Ellis and ClappKato et al., 2014a,Reference Kato, Ellis, Pauw and Carusob). Likewise, the OECD Secretariat has, especially as regards the investment strand, produced output addressing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

In terms of factors shaping the OECD output, the institutional worldview played a more significant role, particularly as regards defining climate finance in economic and development terms. The overarching worldview of the OECD is one framing issues in economic terms and highlighting economic instruments (Reference Carroll and KellowCarroll and Kellow, 2011; Reference RuffingRuffing, 2010), which is evident in the OECD climate finance output. In the case of climate finance, the influence of the worldview included the emphasis on efficiency and the link with fossil fuel subsidy reform, carbon pricing and institutional investment, as well as the development strand’s framing of public climate finance as a subtype of development aid. The differences between the two strands are rooted not only in the worldviews of the different directorates, rather than the worldview of the OECD as a whole, but also in the worldview of the representatives of the ministries that each directorate interacts with. One example of such representatives are development ministry officials in the case of the DAC. There are also framings specific to each strand, that is, public climate finance as development aid and the link to economic instruments respectively. Due to the link to economic instruments, economisation was more pronounced in the case of the investment strand.

Although member state officials were involved in drafting much of the output, staff of the Secretariat attempted to push the envelope and as far as possible act independently of the member states. Nonetheless, the OECD bureaucracy had to ensure that the organisational output was acceptable to its principal. A key element of this is that the OECD is heavily involved in the day-to-day governance of climate finance (unlike the IMF and the G20); thus any figures published by the DAC would be used in discussions of whether developed countries are living up to their commitments. Hence, OECD output could have substantial consequences for its member states, and therefore the OECD member circle of developed countries are sceptical of output that goes against their preferences. Even though the output stemming solely from the OECD Secretariat is more independent of member states than that of the OECD as a whole, member state representatives are allowed to comment on it. Furthermore, the OECD Secretariat’s budget is determined by member states, giving them the discretion to allocate funds between activities and parts of the Secretariat depending on how beneficial or counterproductive they think they are (Reference Carroll and KellowCarroll and Kellow, 2011). All things considered, the autonomy of the OECD bureaucracy constitutes an important scope condition for the influence of its bureaucracy.

Finally, institutional interaction has been more influential in terms of inducing the OECD to address climate finance than regarding how it is has addressed it. The G20 has told the OECD Secretariat to analyse particular issues but has not said how the OECD should address the issue. The UNFCCC has been more influential in this respect, as the OECD output has addressed UNFCCC commitments (most notably the USD 100 billion target) and principles (e.g. CBDR). The former has played a much more central role in the OECD output, as is evident from the publications addressing how to reach the USD 100 billion target. Yet, the principles have often only been addressed in brief paragraphs or text boxes, which have acknowledged their importance without granting them a central place. Finally, the institutions that the OECD has interacted with in terms of producing joint publications or through workshops and seminars have also shaped the OECD output, inter alia through cognitive interaction. These institutions include (in the cases of both strands) multilateral development banks (MDBs), private research institutions and think tanks (most notably the Climate Policy Initiative [CPI]), and International Organisations such as the International Energy Agency (IEA) or United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). In the case of the development strand, it also involves national development agencies, and in the investment strand, private actors such as banks and institutional investors. This interaction has mainly been cognitive in terms of shaping how the OECD defines what key concepts are. As an important example of this, the OECD revised its guidelines for using the Rio adaptation marker so that they now are more similar to the guidelines used by the MDBs (UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance, 2018).

11.3 Consequences

11.3.1 International Consequences

At the international level, the OECD has occupied a central position in a tight web of international institutions addressing climate finance, particularly those focusing on producing knowledge about climate finance. The central role of the OECD has meant that economisation in the shape of the OECD framing climate finance in economic terms has spilled over onto the agendas of other institutions. These institutions have influenced the OECD and have been influenced in return, predominantly via cognitive mechanisms. The G20 has been cognitively influenced by the OECD (mainly the Secretariat) through the reports the OECD provided it as well as OECD Secretariat officials participating in G20 workshops, both of which were used by the G20 Study Groups as material for producing their own reports. These reports focused on OECD areas of expertise, specifically on climate finance tracking and fossil fuel subsidy reform (OECD Secretariat, 2011; World Bank Group et al., 2011). The fact that these reports have been utilised by the G20 meant that they have contributed to supporting the donor-driven climate finance system, in which the important decisions about climate finance have been made by donor governments individually (see Chapter 10). The OECD did not create this system, but its reports on how to make it work in an effective and efficient way have supported its operations by producing cognitive knowledge (domestic and international) actors have been able to utilise.

The influence on the UNFCCC is most direct in the case of cognitive influence on the SCF. First, there is the influence via the OECD member states that tend to rely on DAC data when they report their climate finance to the UNFCCC in their biannual reports. This influence is important not only at the level of the individual country but also because the SCF uses the climate finance figures in the biannual reports to estimate total flows of climate finance. The SCF also relies heavily on OECD DAC figures when it estimates the allocation of public bilateral climate finance for inter alia adaptation and mitigation, to different groups of countries (e.g. Small Island Developing States and Least Developed Countries, different regions) and for gender-oriented projects. Second, the SCF has also relied on OECD data on private investments mobilised by bilateral and regional institutions as well as on fossil fuel subsidies and investment in fossil fuels, recognising the OECD’s expert authority regarding these subjects (UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance, 2014; 2016, 2018).

Beyond the SCF, the responses from the UNFCCC to the OECD output have been more mixed. The question of what counts as climate finance has been a heated topic in the negotiations since before COP15, and the role of the OECD in this has been controversial (Reference Weikmans and RobertsWeikmans and Roberts, 2019). Particularly the 2015 OECD and CPI report on climate mobilised developed countries, and its finding that USD 62 billion had been mobilised was criticised by negotiators from developing countries (Reference SethiSethi, 2015). Much of the criticism concerned the CPI and OECD’s reliance on inflated figures reported by developed countries and ignoring the question of additionality. While there was also contestation over these issues in the SCF, the SCF as a technical body was more prone to utilising OECD data (together with data from other sources) than the more political body of the UNFCCC climate finance negotiations. While there was some overlap in terms the officials involved in the SCF and the climate finance negotiations, the more technical mandate of the SCF (UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance, 2020), this meant that the technical (cognitive) knowledge produced by the OECD was more acceptable to the SCF than to the UNFCCC climate negotiations. Normative influences were very limited, since climate finance was too politicised in the UNFCCC and the OECD was too much of a club for developed countries for the OECD to exert direct influence over how normative questions were addressed, although it implicitly supported the donor-driven system. Yet, incentive-based influences mattered in terms of the DAC figures showing how far developed countries contribute climate finance towards their UNFCCC commitments.

The network of institutions producing knowledge about climate finance also includes several institutions with which the OECD has co-produced output. In these cases, the interaction between the institutions consists of two-way cognitive learning processes influencing the OECD as well as the other institutions. These institutions include the MDBs, particularly the World Bank, which the OECD Secretariat has collaborated with on several of its reports and workshops (OECD and World Bank, 2016; OECD et al., 2018; World Bank Group et al., 2011). Beyond the World Bank, there has been a cognitive influence running in both directions between the OECD Secretariat and the MDBs as a group, in which they have collectively been developing their cognitive ideas about climate finance. This has been the case both as regards mobilising private finance (of which the MDBs have considerable practical experience) and tracking multilateral climate finance. Collaboration with the IEA is more limited than one might expect given the close relationship between the two institutions (also compared to the case of fossil fuel subsidies), but has nonetheless resulted in joint publications on climate finance by the OECD–IEA Climate Change Expert Groups (e.g. Reference Kato, Ellis and ClappKato et al., 2014b; Reference Vallejo, Moarif and HalimanjayaVallejo et al., 2017).

The institutions providing knowledge about climate finance also include non-UNFCCC UN institutions, particularly United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and UNEP. Both UNEP and UNDP have collaborated with the OECD Secretariat on publications, in the case of UNEP and the UNEP Finance InitiativeFootnote 1 on (especially infrastructure) investment (OECD et al., 2018), in the case of UNDP on the relationship between climate finance and development.

Beyond intergovernmental institutions, the OECD has also had a considerable influence on non-state actors and institutions. Although environmental non-government organisations (NGOs) have voiced criticism similar to that of the UNFCCC negotiators from developing countries (Climate Action Network Europe, 2015a), and they have also relied on OECD DAC data and often utilised these data (Climate Action Network Europe, 2015b). Research institutions and think tanks such as the CPI, World Resources Institute or the Overseas Development Institute have also utilised OECD data, as well as collaborating with the OECD on some of its output, most notably the 2015 OECD and CPI report (interview with senior OECD official, 12 May 2015). Finally, corporate actors, in particular actors from the financial sector such as banks and pension trusts, have been influenced by output from the OECD investment strand. This includes participation in workshops and seminars arranged by the OECD Secretariat and drawing on OECD publications, and participating actively in OECD networks such as the Research Collaborative on Tracking Finance for Climate Action (OECD, 2018c, 2020c).

11.3.2 Domestic

Regarding the domestic level, the influence of the OECD has also mainly been cognitive and has involved government officials rather than non-governmental constituencies such as NGOs or the general public. This is evident in all the five countries studied, even the non-OECD countries India and Indonesia. The DAC reporting requirements have involved officials in each DAC country, setting in motion the production of knowledge about climate aspects of their own ODA and framing existing ODA projects as climate projects. DAC reporting not only affects their cognitive understanding of their own climate finance; it also provides them with knowledge about other countries’ climate finance. All DAC countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom and Denmark, have treated climate finance as a subtype of development aid.

As regards both the development and investment strands, the OECD has played an important role as a provider of knowledge and ways of understanding climate finance. As regards producing data and statistics on public bilateral climate finance, the OECD enjoys a quasi-monopoly, which has meant that even those critical of the OECD data have to rely them, as is evident in the case of India (see later). This influence has also been important regarding climate-related investment, which is a new subject that people, including government officials, had little understanding of and regarding which only limited knowledge had been produced. OECD publications, workshops and seminars were among the first to address investment as a climate finance issue, at least beyond academia and think tanks. The OECD Secretariat’s expertise on investment and development has played an important role for its authority on these issues in the eyes of government officials. Especially as regards investment, reframing particular kinds of already existing finance as climate finance has meant that actors, including government actors, already working with investment have been able to address it in a different way. All the five countries studied here have been active in the investment strand.

Neither of the strands has played a major incentive-based role, yet DAC reporting has provided opportunities for incentivising countries to provide more climate finance, as well as more climate finance in line with equity-based ideas such as prioritising vulnerable countries and adaptation. Such incentives may take the shape of reputational costs of not living up to climate finance commitments, hence reducing a state’s credibility when future commitments (regarding climate finance or other issues) are negotiated (on reputational costs and benefits, see Reference AbbottAbbott, 2014). The fact that there are no individual country obligations to provide a given amount of climate finance limits the impact of such reputational costs, yet the fact that countries over-code their climate finance indicates that they are concerned about being seen as providing sufficient amounts of climate finance. Furthermore, the amounts of public climate finance provided– according to the DAC (OECD, 2019b) – increased consistently during the period 2013–17, indicating that countries are responding seriously to the commitment of providing increasing amounts of climate finance, even though these amounts may not be sufficient to reach the USD 100 billion target.

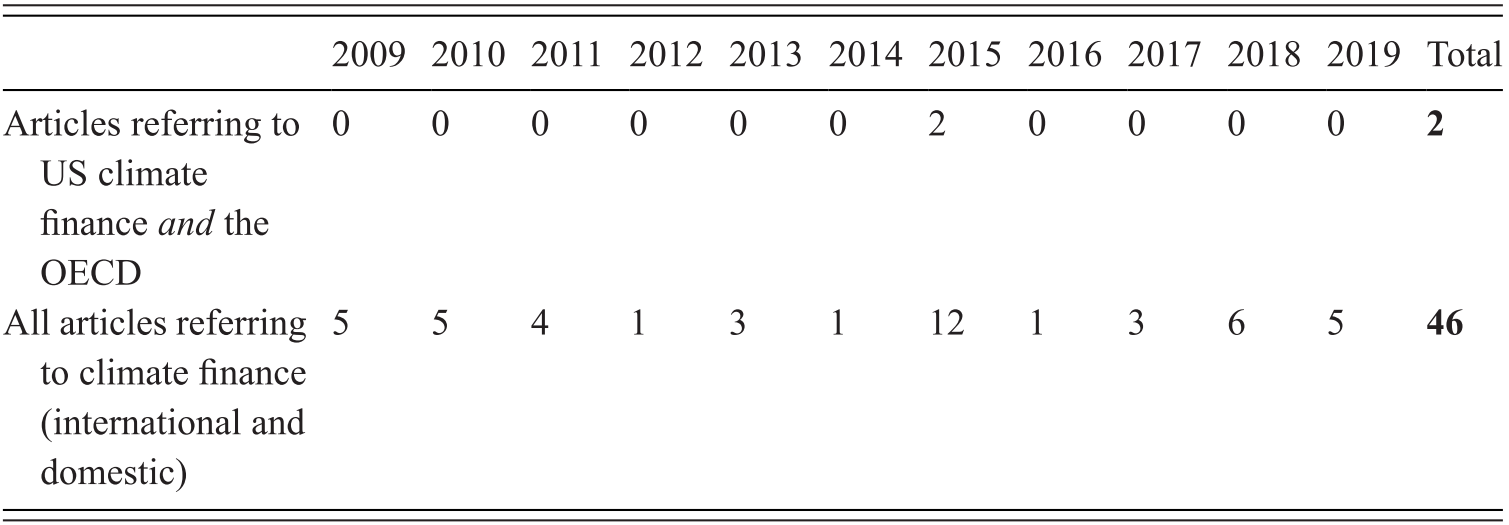

The United States has consistently preferred the OECD to the UNFCCC as an institution for monitoring climate finance. The United States has also consistently reported to the DAC committee even when the Trump administration ceased to report its climate finance flows to the UNFCCC, and also referred to the OECD’s figures and argued that they may underestimate actual flows (Reference SethiSethi, 2015). Yet, the fact that US public climate finance has been shaped more by domestic than international politics (see Chapter 10) and that the United States interacts with a wide range of institutions regarding climate finance, many of them with headquarters in Washington, DC (the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank), means that OECD influence on US climate finance can be difficult to discern from other factors. On the public agenda, the OECD has not been linked to US climate finance, except for two articles in 2015 (see Table 11.1), which referred to the OECD and CPI report on progress towards the USD 100 billion target (Reference DavenportDavenport, 2015; Reference PorterPorter, 2015). Importantly, the criticism of the level of US climate finance from officials and NGOs from European and developing countries (including India) was placed in the context of the report, thus adding to the normative pressure on the United States to provide more climate finance. This is an example of how OECD reporting makes it possible to criticise countries for not providing enough climate finance. In this way, the OECD makes it easier to hold countries accountable for equity-oriented normative ideas, although it is possible that another, more equity-oriented institution established in the UNFCCC would have taken its place had it not reported on climate finance. Furthermore, on a very fundamental level, the OECD has supported the CBDR-based normative idea that developed countries have an obligation to provide climate finance.

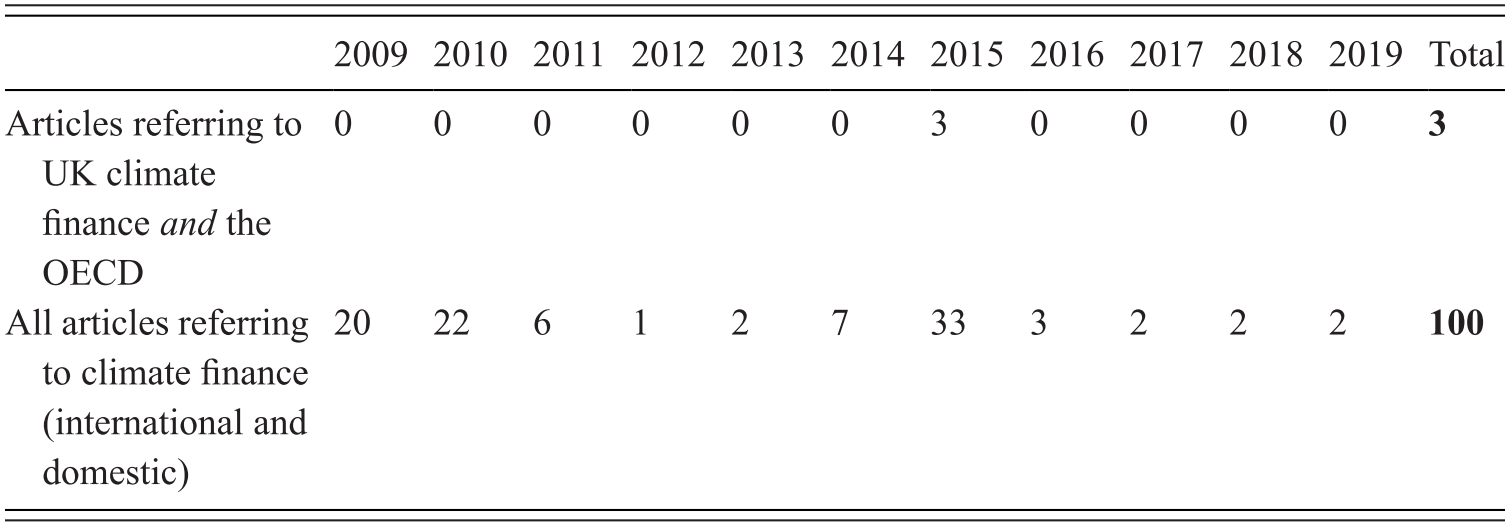

The United Kingdom is a prominent example of a country that has played an active role in international climate finance discussions, as well as having increased its public climate finance and reported the same climate finance data to the OECD DAC and to the UNFCCC (UK Government 2019). The UK has stressed normative ideas such as efficiency and the importance of leveraging private finance (Reference Pickering, Skovgaard, Kim, Roberts, Rossati, Stadelmann and ReichPickering et al., 2015b; Reference SkovgaardSkovgaard, 2017b; UK Government, 2019). UK government representatives have also been highly active in the OECD investment strand, notably the Forum on Green Finance and Investment, in which representatives of inter alia the Bank of England have presented their perspectives on green investment and finance issues. On the public agenda (see Table 11.2), a picture similar to the one of the United States emerges: it was not until 2015 that newspaper articles linked OECD data and UK climate finance. Furthermore, in these articles the OECD estimates of climate finance provided a context for NGOs to criticise the United Kingdom (and other developed countries) for not providing sufficient amounts of climate finance, including shaming the United Kingdom for not contributing as much as France and Germany (Reference MathiesenMathiesen, 2015; Reference NeslenNeslen, 2015).

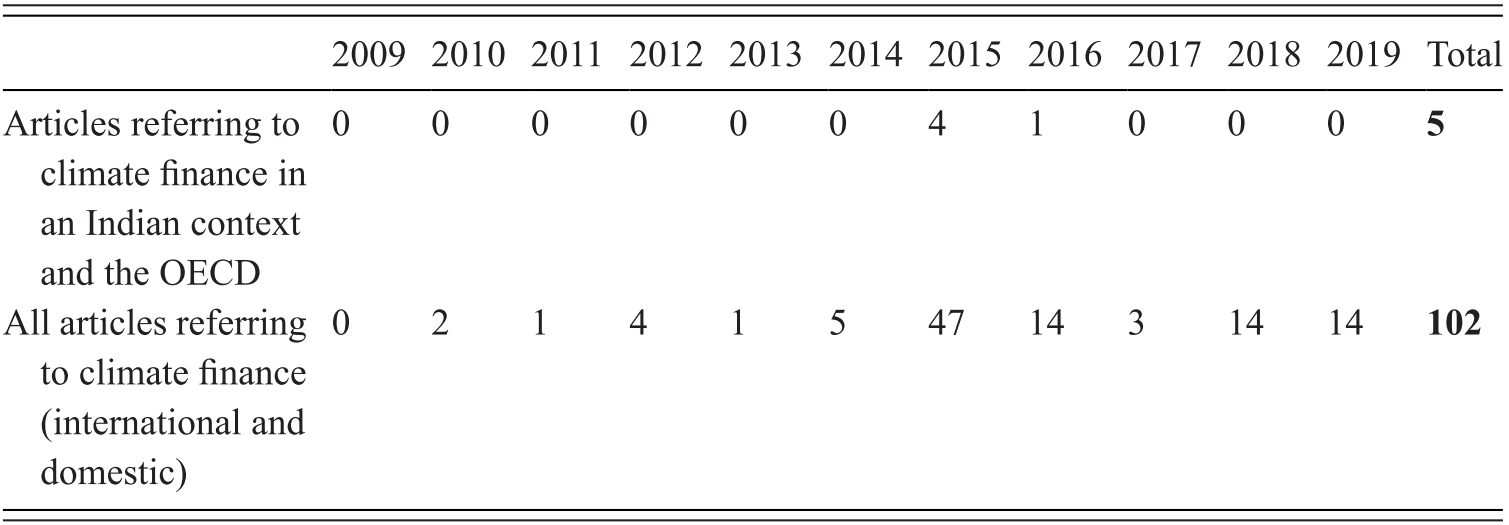

A criticism of the OECD is that the DAC countries can provide as much climate finance as they wish to and also report as much as they wish to due to the limited scrutiny of the DAC figures, an issue often raised by the government of India (Reference DasguptaDasgupta and Climate Finance Unit, 2015; Indian Ministry of Finance, 2019). Thus, the Indian government has been highly critical of the current system of donor-driven climate finance. Specifically, it has criticised both the OECD’s estimate of global climate flows and the use of OECD DAC data to calculate individual countries’ climate finance contributions (see inter alia Reference DasguptaDasgupta and Climate Finance Unit, 2015; Indian Ministry of Finance, 2018). Nonetheless, India has as a partner country participated in meetings arranged by the DAC Environet Working Group climate finance meetings. A crucial factor explaining this difference is that the OECD’s output on investment has been more aligned with the preferences of the Indian government (which is in favour of leveraging private finance, Indian Ministry of Finance, 2019) than the development strand output. On the public agenda, as in the United States and the United Kingdom, the OECD link between the OECD and climate finance in an Indian context has hardly featured before or after 2015, 2016 being the sole exception (see Table 11.3). Also similar to the US and the UK public agendas, it is the OECD’s estimate of global climate finance on progress towards the USD 100 billion target that receives the attention, and the findings are used to shame developed countries for not living up to their promises (Reference MohanMohan, 2015a). Yet, unlike the US and UK newspapers, the veracity of the OECD’s figures are called into question, and the Indian government’s claim that these figures are exaggerated is referred to (Reference ByravanByravan, 2015; The Times of India, 2015).

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles referring to climate finance in an Indian context and the OECD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| All articles referring to climate finance (international and domestic) | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 47 | 14 | 3 | 14 | 14 | 102 |

Like India, Indonesia is an OECD partner country, which has participated in a few of the investment and (to a lesser degree) development strand meetings but has been less vocally critical of the DAC estimates of climate finance. Both Indonesia and India have participated actively in the activities under the investment strand, including the Forum on Green Finance and Investment, since this forum is less controversial, as it has not interfered with the USD 100 billion target and other issues discussed in the UNFCCC.

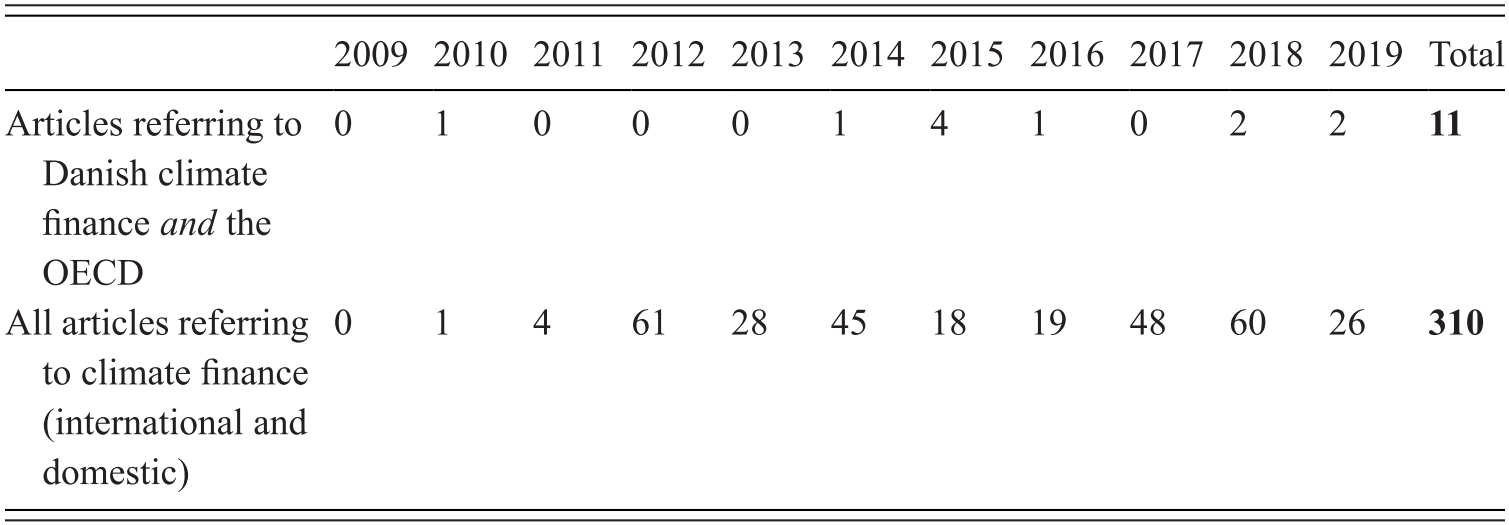

Denmark is like the United Kingdom, a country that has increased its public climate finance and reports the same climate finance data to the OECD DAC as to the UNFCCC (Danish Ministry of Energy, 2017). Also similarly to the United Kingdom, the Danish government has stressed normative ideas such as efficiency and the importance of leveraging private finance (Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2017; Reference Pickering, Skovgaard, Kim, Roberts, Rossati, Stadelmann and ReichPickering et al., 2015b; Reference SkovgaardSkovgaard, 2017b). In the investment strand, at the OECD meetings and forums Denmark has played a very active role considering its small size compared to the other countries studied, often highlighting Danish experiences with climate investment. The public agenda follows a pattern similar to that of the other countries, although the link between the OECD and Danish climate finance is also present beyond the peak in 2015 (see Table 11.4). The focus is also on NGOs shaming the government for not providing sufficient amounts of climate finance and this finance not being new and additional climate finance (Reference Hannestad and BostrupHannestad and Bostrup, 2019). Yet, there are also references to the OECD’s analysis of climate finance, including the shares of private finance (Reference Thomsen and HannestadThomsen and Hannestad, 2015).

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles referring to Danish climate finance and the OECD | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 11 |

| All articles referring to climate finance (international and domestic) | 0 | 1 | 4 | 61 | 28 | 45 | 18 | 19 | 48 | 60 | 26 | 310 |

11.4 Summary

The OECD’s output on climate finance is mainly knowledge-based and can be divided into two strands addressing public climate finance framed as a subtype of development aid and as an investment issue respectively. In both strands, the OECD has emphasised economic normative ideas, particularly the importance of efficiency, and de facto, especially in the development strand, contributed to the current climate finance system in which the important decisions regarding allocation are reached by developed contributor countries. Since investment is more of an economic issue than development, it is unsurprising that economisation (in terms of framing) was more pronounced within the investment strand. In both strands, the OECD has played a role as a key (in the development strand the key) knowledge provider. Institutional interaction, especially with the UNFCCC, and member states has been an important factor in inducing the OECD to address climate finance, whereas member states and the institutional worldview have been important in shaping how the institution has addressed it. The OECD member states and the OECD bureaucracy’s autonomy vis-à-vis them have acted as a scope condition for how far the OECD bureaucracy has been able to go. Importantly, the institutional worldview has differed to some degree between the directorates responsible for the two strands, as the directorates as well as the member state officials they have interacted with have differed and had different worldviews. Specifically, the development strand has mainly involved the Development Co-operation Directorate and development ministries, and the investment strand the Environment and the Financial and Enterprise Affairs Directorates and the environment and the finance (and economics) ministries. The OECD output has mainly been influential via cognitive mechanisms, and more pronounced at the international than the domestic levels. The UNFCCC has most notably been influenced by OECD reporting on the total and country contributions of climate finance (from the development strand), whereas the investment strand has influenced cognitive ideas about the role of investment at the domestic level as well as in international institutions including the G20, MDBs and the UNFCCC. Yet, the OECD’s quasi-monopoly on public climate finance statistics has also led to important cognitive influences at the domestic level, which is evident in how their data have been used both by the government and by NGOs seeking to shame developed country governments for providing insufficient amounts of climate finance. The influence on the public agenda was most pronounced in connection with COP21 in 2015.