Democracy

Democracy is one of the most contested and controversial concepts in the English language. The heated debate over what is and what is not a democracy helps to explain why the term is regularly used as an example of an “essentially contested” concept over which there is consistent disagreement about its definition and meaning (Gallie Reference Gallie1955). Even if we could all agree that a democracy is a political system in which the government is selected by the people and respects rights and liberties, we would likely disagree about exactly what combination of rights and liberties are the most important. Consequently, there is no uniform understanding of exactly what democracy means or how it should be practiced, even among citizens of the same country (Schaffer Reference Schaffer2000). This is evidenced by the great variety of political systems employed in democratic states and the very different ways in which they rank values such as liberty and equality (Berlin Reference Berlin1958).

In Africa, these complexities are compounded by the question of whether democracy is or is not a colonial imposition unsuited to domestic realities. This conversation is not new, but has its roots in the 1920s and 1930s, when debates emerged over whom should be given the franchise in colonial territories with a large white settler population. It continued after independence, when leaders such as Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere argued that multiparty competition was “unAfrican,” and that the one-party state was a more suitable embodiment of traditional African values of community and consensus.

The idea that democracy is a Western imposition continues to have great resonance, in part because the “foreign” roots of the word itself are so very visible. In the surveys conducted by the Afrobarometer, for example, the English word “democracy” is used even when all other words are translated.Footnote 1 This is done to ensure consistency of understanding, but to some it may convey the impression that African languages do not have sufficiently similar words and concepts, and so sustains the notion that democracy is something alien (Zack-Williams Reference Zack-Williams2001).

Over the last seventy years, the debate about the feasibility of democracy in Africa has returned with cyclical regularity: first, following a number of civil wars and coups in the late 1960s and 1970s, which suggested that multiparty politics might do more harm than good in diverse societies with weak institutions, and then again in the wake of the disappointing progress toward democratic consolidation following the reintroduction of multiparty elections in the 1990s. In each of these manifestations, the central question has been the same, but the context and nature of the debate have varied. In the 1970s, the most common cases cited as alternative models for the continent to follow were the Soviet Union internationally and Côte d’Ivoire and Tanzania domestically. More recently, these countries have been replaced by China on the international front, while Rwanda has become the poster child for authoritarian pathways to development on the continent.

Across all of these periods, the arguments of African leaders were not made in a vacuum, but were challenged, refracted, and sometimes endorsed by other leaders, intellectuals, the media, and citizens themselves. Figures such as Wangari Maathai (Reference Maathai2003), the Kenyan Nobel Prize Laureate, and Emmanuel Gyimah-Boadi (Reference Gyimah-Boadi2004), the Ghanaian political scientist, have consistently argued that liberal democracy is achievable and should be the ultimate aim of African societies. Others, such as Claude Ake (Reference Ake2000) and George Ayittey (Reference Ayittey2006), have suggested that the communal focus of African political identity does not sit well with European notions of liberal democracy, in which the voter is expected to operate as a utility-maximizing individual. In so doing, Ake and Ayittey raise the thorny question of whether the problem is democracy per se, or the particular type of democracy that has been tried on the continent as a result of the tendency to implement American, British, and French models (Decker & Arrington Reference Decker and Arrington2015).

In this way, the attention of both political leaders and academics has cohered on the question of what “African democracy” should look like, and the conclusion has often been that, in contrast to “Western democracy,” it should place a greater focus on participation and consensus and be less concerned with individuals casting ballots in multiparty elections. Recent debates reflect similar preoccupations. One has focused on the extent to which democratic practices can be identified in African societies past and present (Kasanda Reference Kasanda2018). Another asks whether certain features of African society are incompatible with multiparty democracy, and if democracy has the same meaning for those on the continent that it does for the citizens of European and North American states (Bratton & Mattes Reference Bratton and Mattes2001; Hountondji Reference Hountondji2002). This article provides an overview of these debates, foregrounding the deep political thought on the topic by African leaders and academics.

Against the notion that modern democracy is a Western imposition, we suggest that there is considerable evidence of “fragments of democracy” in the pre-colonial era (Freund Reference Freund2016; Cheeseman Reference Cheeseman2015). We also demonstrate that key democratic institutions, such as competitive elections, have become deeply embedded in African political practice (Willis et al. Reference Willis, Lynch and Cheeseman2018). That this is not always recognized, and that “African democracy” is so often imagined to exclude “Western” accountability mechanisms is in part the product of the silencing of democratic practices and histories, first during the colonial era and second in the period of authoritarian rule that followed independence. In both eras, authoritarian leaders at times misunderstood the societies over which they governed, and at times deliberately distorted the past to suit their own political ambitions. Current critiques of democracy, such as that offered by the Rwandan President Paul Kagame, may yet amount to a third period of silencing if they gain ground.

Yet, despite the checkered progress of multiparty politics and the efforts of some leaders to paint it as an alien concept, democracy has become a key touchstone for ordinary citizens and governments alike and is critical to the exercise of legitimate authority. This is not to say that democracy is universally loved, but rather that both nationally representative surveys and patterns of protest suggest that public support for democratic government is not simply an artificial legacy of Western democracy promotion. Rather, it is rooted in the fact that, as in other parts of the world, citizens value having a voice in the decisions that affect their own lives. Indeed, drawing on survey data from across the continent, we demonstrate that most African societies favor a form of what we term “consensual democracy,” an approach to government that combines a strong commitment to multiparty elections and accountability with a concern for unity and stability. The most remarkable thing about the idea of democracy in sub-Saharan Africa, then, is that despite all of the controversy, it remains one of the most compelling ideals in political life—even in many countries in which it is has yet to be realized.

The First Period of Democratic Silencing: Colonialism and the Rise of Fragile Authoritarianism

The first wave of democratic silencing took place under colonial rule, when the policies enforced by metropolitan leaders and officials undermined the checks and balances that had developed in many African societies. Although pre-colonial systems of government were not modern democracies in the sense of choosing leaders through competitive elections, neither were they devoid of elements of democratic practice. In the 1800s, centralized states capable of mass repression were relatively rare and only covered around 10 to 15 percent of the continent. While a small number of kingdoms and empires operated on clearly authoritarian foundations—not least in that they kept or traded slaves—many communities lived on a much smaller scale and did not recognize the right of any leader to exert totalitarian control. Many of these groups, such as the acephalous Igbo communities that lived in what is now southeast Nigeria, placed considerable limits on the power of their “chief” (Ekpo & Chime Reference Ekpo and Chime2016). Even where more centralized forms of authority existed, low population density typically meant that families could escape abusive systems through migration, which provided a strong incentive for leaders to moderate their demands (Herbst Reference Herbst1990). Thus, if we recognize that democracy is not just a way of electing a government but is also a set of political arrangements that promotes participation and accountability, it can be argued that a number of African societies have a longstanding tradition of democratic practices (Diop Reference Diop1996; Ayitteh Reference Ayittey1992).

More specifically, many indigenous African political systems were democratic in at least three respects. First, there was a considerable degree of political participation, often involving the whole village, talking issues out until consensus was reached on matters concerning the community. This form of participation was institutionalized in the form of the kgotla (for the Tswana/Bamangwato), kuta (Barotse/Lozi), and zango (Lunda/North-Western Zambia) systems in Southern Africa (Martin Reference Martin2012). In Central and West Africa, participation mainly took place through the palaver (village assembly). For many East African communities, it was the baraza. As Bill Freund (Reference Freund2016) has argued, these arenas were no democratic panacea—in many cases, they were dominated by older, wealthy men. But they nonetheless represented a space in which village elders would present issues to citizens, and where decisions could be reached through a deliberative process in which popular consent played a significant role.

Second, even some of the more hierarchical African political systems offered a degree of political representation. Centralized kingdoms, such as the Ashanti of present-day Ghana, Bemba in modern Zambia (Roberts Reference Roberts1973), Songhai, Yoruba, and Mali, all in West Africa (McKissack & McKissackReference McKissack and McKissack1994), were organized according to villages, provinces, and states, and these were represented in the King’s Councils or governing Courts, also known as Kuta systems. In many cases, a kind of balance was maintained that allowed the representation of various clans and lineage groups and in some cases women. In the constitution of the Mali Empire, the Kurukan Funga Charter or the Manden Charter of 1236, women were guaranteed equal representation with men in decision-making (Akyeampong Reference Akyeampong2006). Indeed, in some ways the provisions of the Manden Charter are comparable to those found in the Bill of Rights (1689), the Declaration of the Right of Man and the Citizen (1789), and the Magna Carta (1215–1297).

Third, a small but significant number of indigenous African political systems featured elements of accountability, including some of the earliest recorded elections, albeit on a very limited scale. The pre-colonial Mossi Empire, for instance, was a constitutional monarchy in which the monarch, the Moro Naba, was elected from a list of eligible candidates—that is, those with the correct lineage. Although only a small number of individuals qualified to be considered, this model nonetheless meant that merit was institutionalized as a criterion for office. Moreover, the authority of the Mossi Emperor was not absolute; he lacked the power to dismiss ministers once they had been invested, and he was bound to obey the constitution or be deposed. The former provision was partly designed to ensure that all social classes were represented within the government, thus eliminating the possibility of power being usurped by the nobility (Tiky Reference Tiky2011).

More broadly, chiefs or kings were often held accountable not only for their actions, but for natural catastrophes, such as famines, epidemics, floods, and droughts (Ake Reference Ake1991:34). To return to the case of the Igbo of Nigeria, the leader, known as eze or obi, governed with the help of what was effectively a Privy Council and was accountable to it for his actions (Ezenagu Reference Ezenagu2017). While the position was hereditary, the oba could be impeached if he abused his power—and could also be violently removed. To ensure accountability, the elders in the Council were often commoners, not members of the royal family or the nobility, to allow for the representation of ordinary citizens. Among the Lozi in Zambia, the head of the Council (Kuta) was a commoner, known as Ngambela or Prime Minister (Mainga Reference Mainga1973).

It is therefore deeply misleading to depict pre-colonial Africa as being characterized solely by authoritarian rule (Wiredu Reference Wiredu1998; Lauer Reference Lauer, Lauer, Nana and Anderson2011). Indeed, while to the best of our knowledge there is no indigenous African word that carries quite the same meaning as democracy, there are words for freedom—uhuru in Swahili, buntungwa in Bemba, tukuluho in Lozi—and rights (liswanelo in Lozi). There are also several words for government, as well as terms for village assemblies that foreground the significance of popular participation, such as kuta, kgotla, zango, or indaba. What is perhaps missing in African languages is words and concepts describing political contestation; competition between organized factions is largely absent from the lexicon. But this does not mean that communities did not have a developed language to describe, or a deep conceptualization of, consensual and deliberative forms of decision-making. It is therefore important to keep in mind that although most modern democracies focus on multiparty competition, political theorists have long argued that deliberative democracy—in which decisions are arrived at through reasonable discussion among citizens—would lead to more legitimate and effective government (Gutmann & Thompson Reference Gutmann and Thompson2009).

That much of this history is not widely known is not an accident, but rather the product of the way that the past has been discussed by successive governments, and how it has been taught—and in many cases not taught—in schools (Ouzman Reference Ouzman, Smith and Wobst2005). Colonial governments misunderstood the African societies that they had come to govern, introducing a range of political processes that had an inherently authoritarian bias. Because colonial governments tended to believe that Africans lived in extremely hierarchical and clearly demarcated “tribes,” they centralized authority under traditional leaders, intensifying ethnic differences while simultaneously empowering figures with little legitimacy to exert authority over large communities (Ranger Reference Ranger, Grinker, Lubkemann and Steiner1997).

This process was not solely driven by colonial administrators. As Leroy Vail (Reference Vail1991) has argued, a range of cultural and political entrepreneurs worked hard to create stronger and more distinctive identities for their communities, in many cases carefully editing history in order to legitimate the concentration of power under a more powerful set of leaders. Following Archie Mafeje (Reference Mafeje1971) and John Iliffe (Reference Iliffe2017), we might say that colonial governments believed in tribes, and Africans gave them tribes to believe in. In this way, colonial regimes and African intellectual and political leaders co-produced the rise of more centralized and clearly demarcated ethnic groups, and hence the decentralized despotism that followed colonial rule (Mamdani Reference Mamdani1996). Similarly, by importing sexist European notions that wage labor and political decisions should be made by men, colonial governments weakened the position of women within society. These processes fundamentally undermined the fragile limits on the abuse of power that had existed in many pre-colonial societies.

There were some exceptions to this general rule, of course. In some French colonies, most notably Senegal, the policy of “assimilation” was more than just a rhetorical promise; this led to Africans—at least educated Africans in urban areas—being able to enjoy considerably greater political freedom than in other territories (Schaffer Reference Schaffer2000). But for the most part, colonial governments invested considerable resources and energy in denying demands for political representation while strengthening and maintaining “tribal” identities, lest “detribalized” individuals unite to present a common front against colonialism (Posner Reference Posner2005:Ch 1 & 2). Such efforts went hand in hand with the widespread use of repression and censorship to try to prevent the growth of African nationalism (Anderson Reference Anderson2005). Taken together, these changes eroded some of the careful checks and balances that had evolved in pre-colonial political institutions, predisposing the continent toward a form of “fragile authoritarianism” (Cheeseman & Fisher Reference Cheeseman and Fisher2019).

The authoritarian legislation and structures developed under colonial rule were compounded by a consistent narrative that—even when administrators and officials began to focus on the introduction of the political arrangements required for self-rule—implied the continent was not capable of democratic government. As Uday Mehta (Reference Mehta2018) has argued, the language of colonial rule was often one of “presumed infantilism,” in which Africans were seen to be children who needed educating and civilizing before they could assume political rights and civil liberties. When the British government finally produced a report on introducing self-rule in 1960, after years of prevaricating, it was entitled “Democracy in backward countries.”Footnote 2

This idea that Africa is not ready for democracy has proved to be remarkably durable, despite the many changes that have taken place on the continent since the 1960s. One reason for this is that it has served the interests of the continent’s post-colonial leaders, many of whom had good reason to avoid being held accountable to democratic ideals.

The Second Period of Democratic Silencing: Freedom, Unity, and the Philosopher Kings

The second period of democratic silencing occurred after independence, as leaders who had taken power in multiparty elections sought to consolidate their power by curtailing political rights and civil liberties. The argument that democratic institutions represented an alien form of government was particularly powerful in this era for four reasons. First, it aligned with two of the dominant themes of the early post-colonial period: the need for Africanization, and the imperative of development. Second, as we have seen, the debate about whether African states were ready for independence had already foregrounded a range of arguments about why democratic arrangements might not work as intended. Third, it piggybacked on anti-colonial sentiment and a broader rejection of imperial values. Finally, few nationalist movements or leaders had actually framed their struggles in terms of “democracy” itself.

The last point is often overlooked in histories of democracy on the continent, but it played an important role in shaping how subsequent debates unfolded. Had liberation movements explicitly argued that they were fighting for democracy in the period from 1940 to 1960, it would have been harder to subsequently claim that such arrangements were problematic. But by and large, this was not the case. Instead, Africa’s Philosopher Kings (Mazrui Reference Mazrui1990), such as Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah and Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere, wrote of the value of key elements of democracy—self-mastery, political participation, equality—but couched this in terms of “freedom and unity” (Nyerere Reference Nyerere1964) rather than democracy itself. When Nkrumah wrote of the need for the pan-African struggle to continue in 1961, four years after Ghanaian independence, he called his book I Speak of Freedom, and in the preface he wrote of the need to make Africa “free” rather than to make Africa democratic. Similarly, the Freedom Charter—which was officially adopted as the definitive statement of South Africa’s African National Congress in 1955—goes into great detail about the need to protect a wide range of rights and liberties, but it never mentions the term “democracy.”

This is not to say that democracy never appeared in the discussions and debates of this period. In the negotiations that preceded independence, attention shifted to the kinds of political systems that would be best suited for African states. Especially where nationalist movements had different hopes and fears for the post-colonial period, this led to heated disagreement about the most suitable political arrangements. In Kenya, for example, rival African nationalist parties, along with groups that represented Asian and European interests, debated whether a centralized or “majimbo” (federalist) political system would be more suited to the country’s needs (Anderson Reference Anderson2005). These negotiations happened relatively late, however, and did not always reach a mass audience.

Many of the speeches made by intellectuals and political leaders also included a reference to democracy, but rarely was it their main focus. Félix Houphouët-Boigny, the first president of Côte d’Ivoire, named his political party the African Democratic Rally (RDA) and referenced democracy in his speech to the United Nations General Assembly in 1957. But his main aim in doing so was to encourage French colonies to retain ties with the metropole by arguing that France was committed to allowing African peoples to “administer their own affairs democratically.” When it came to his summary of the kind of country that he wanted to build, Houphouët-Boigny placed his emphasis elsewhere, talking instead of brotherhood and equality (Smulewicz-Zucker Reference Smulewicz-Zucker2017:53–54). Similarly, Amilcar Cabral, the great theorist and nationalist leader of what is now Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde, lauded the “atmosphere of great enthusiasm” with which the people engaged in general elections in Guinea Bissau in 1972. However, “(n)owhere in Cabral’s writings do we find, seriously conceptualized, any realistic way of making the revolutionary-democratic alternative come true” (Rudebeck Reference Rudebeck2006:5). One important exception to this rule was K.A. Busia, the Ghanaian Prime Minister between 1969 and 1972, who published Africa in Search of Democracy in 1967. Tellingly, however, Busia did not write the book prior to independence or when he was in power, but in the mid-1960s when he was living in exile, having fled Nkrumah’s increasingly authoritarian government.

The lack of attention to democracy, and to what realizing democratic government would mean, enabled post-colonial leaders to suggest that the key aims of the liberation struggle—freedom, unity, development—could be realized without it. Nyerere, perhaps the most influential advocate of the one-party state the continent has ever had, argued that the essential feature of a political system was not whether it was democratic in a “Western” sense (i.e., that it held elections), but whether it fostered political participation and development. Moreover, Nyerere suggested that the very idea of electing a government by allowing political parties to compete in an election was at odds with traditional mechanisms of decision-making in African societies. These claims reflected Nyerere’s own memories of observing elders within the community resolving their differences by talking them out at length when he was growing up (Stöger-Eising Reference Stöger-Eising2000). His repacking of this heritage to justify the forced consensus of the single-party system, however, left the Tanzanian president with far more power than any of the elders of his childhood could have ever envisioned wielding.

The argument that African societies are inherently communal and so unsuited to liberal democracy, with its assumption of individual voters weighing up their own best interest before casting a ballot, resonated across the continent for a number of reasons (Appiah Reference Appiah2001). For one thing, Nyerere’s focus on the communal nature of African life aligned with other prominent theories, such as the concept of négritude developed by Léopold Sédar Senghor (Reference Senghor1974:270), Senegal’s first president and renowned cultural theorist. For Senghor, communalism was a central feature of black societies around the world. The popularity of Nyerere’s vision also owed much to the fact that by focusing on consensus rather than competition, it offered a solution to one of the greatest threats to post-colonial stability: inter-ethnic conflict. In addition to promoting peace, stability and unity were widely viewed to be necessary for development—an imperative for post-colonial leaders (Young Reference Young1982; Ibhawoh & Dibua Reference Ibhawoh and Dibua2003). At the same time, by emphasizing the value of “traditional” forms of authority and decision-making, Nyerere’s quest for a form of African government, much like his quest for a form of African socialism, reflected a broader concern that colonial political and economic institutions should be Africanized (Karekwaivanane Reference Karekwaivanane2015).

Although there was always a strand of academic thought that highlighted African commitment to accountability (Barkan Reference Barkan1976) and civil liberties (Gyimah-Boadi & Rothchild Reference Gyimah-Boadi and Rothchild1982), Nyerere’s conclusion was not always challenged. In large part, this was because many scholars concurred that African societies were not fertile ground in which to build a modern democratic state. In his seminal essay on the “two publics,” Peter Ekeh (Reference Ekeh1975) suggested that African societies lacked moral commitment to civic norms: “The native sector has become a primordial reservoir of moral obligations, a public entity which one works to preserve and benefit. The Westernized sector has become an amoral civic public from which one seeks to gain, if possible in order to benefit the moral primordial public.” Numerous researchers subsequently echoed Ekeh’s words, using the language of neo-patrimonialism to argue that the “traditional” foundations of African society encouraged a form of highly ethnic and personalized politics that fundamentally undermined the institutional checks and balances that democracy requires (Médard Reference Médard and Clapham1982). Although later scholarship has been highly critical of the neo-patrimonial paradigm, finding that it tended to underestimate the impact that new political institutions exerted on African societies (Erdmann & Engel Reference Erdmann and Engel2007; Pitcher et al. Reference Pitcher, Moran and Johnston2009), at the time, this literature provided a strong intellectual foundation for doubting the feasibility of democracy.

Implementing authoritarianism

In some cases, leaders sought to justify the prohibition of multiparty politics on the basis that they maintained the political rights and civil liberties that really mattered, pioneering a form of African democracy that was different from but no less legitimate than that practiced in the West. While Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta promised to respect civil liberties while constraining political rights, others argued that participation was more important than the right to select the government. Most notably, Kenneth Kaunda, the first president of Zambia, claimed that his single-party system was more democratic than its Western counterparts because it allowed citizens to participate all year round and not only on election day (Sishuwa Reference Sishuwa2016). Tellingly, Kaunda’s defense of the one-party state was accompanied by the gradual weakening of indigenous political systems such as those of the Lozi community, which encouraged the diffusion rather than the consolidation of power. In this manner, a small but significant number of African leaders positioned themselves in the republican tradition of Alexis de Tocqueville (Reference de Tocqueville1838) and Charles Taylor (Reference Taylor2012), emphasizing the importance of political engagement over freedom from government intervention.

The need to justify new political systems with reference to democratic norms and values suggests the legitimizing power of these ideas, even in the predominantly authoritarian 1970s. In most cases, however, governments failed to live up to their early commitments. Especially in countries where multi-party politics fell to military coups, the use of democratic language was often little more than political theatre. This was the case in Mobutu Sese Seko’s Zaire, for example, where a one-party state was created to provide cover for what was effectively a personal dictatorship sustained through coercion. “Have you ever seen an African village with two headmen?” asked the Zairean president when resisting calls for multiparty democracy in the late 1980s. As the prime initiator of the campaign for the reintroduction of democracy in neighboring Zambia recalled, “In posing that question, Mobutu was saying that multipartyism is not African and that there can only be one president and one party because the presence of opposition party leaders means that you are promoting the idea of an alternative president.”Footnote 3

The situation was somewhat different in countries where nationalist parties used their dominant electoral victories to introduce civilian single-party systems. Governments in countries such as Kenya, Senegal, and Zambia were far more likely to maintain a functioning legislature and to hold one-party elections to selects its members, often with considerable turnover of personnel (Opalo Reference Opalo2019). However, while this served to institutionalize elections as a means of legitimating the exercise of authority (Throup Reference Throup1993), it did little to prevent the abuse of power. In Tanzania, for example, those who rejected Nyerere’s approach were prohibited from contesting elections, and by 1979 there were more political prisoners in Tanzania than in apartheid South Africa (Cheeseman Reference Cheeseman2015:43).

Indeed, it is telling that the three countries that genuinely maintained civil liberties and political rights in the 1970s and 1980s were Botswana, Gambia, and Mauritius, the only states that continued to hold regular multiparty politics. In these countries, very different political ideologies came to the fore—paternalistic democracy in Botswana and Gambia, Fabian socialism in Mauritius—and helped to sustain a greater commitment to democratic rights. Outside of these cases, the abuses of power and prolonged economic decline eroded the capacity of authoritarian governments to retain popular support. As a new generation emerged whose formative experience was not the liberation struggle but rather unemployment and corruption, popular sentiment shifted in favor of political change, leading to growing calls for democratic reform (Adekanye Reference Adekanye1995). In many countries, these demands were first made by civil society and religious leaders and then taken up by those political leaders who had been excluded from government over the previous thirty years, culminating in mass mobilization. Yet despite the importance of popular protests to political reform, the reintroduction of multiparty politics is not always seen as the product of a domestic struggle.

A Third Episode of Democratic Silencing? Africa’s “Second Liberation” and the Durability of the Democratic Ideal

Despite the collapse of authoritarian rule in the late 1980s and the fact that it was Botswana and Mauritius that recorded the best economic performance in the first three decades after independence, the idea that multiparty democracy is “unAfrican” has not gone away. Although the early 1990s saw a brief period during which democracy was the “only game in town,” there was never a consensus in favor of political reform among the continent’s political elites (Wamba-dia-Wamba Reference Wamba-dia-Wamba1992). While almost all African countries now hold multiparty elections of one kind or another, many ruling parties have yet to genuinely embrace democratic norms and values (Monga Reference Monga1997). Against this backdrop, the argument that multiparty politics was solely reintroduced by Western powers is often invoked by the continent’s more authoritarian leaders to justify placing tight restrictions on political activity, in what may yet amount to a third episode of democratic silencing. It is no coincidence, for example, that one of the most effective proponents of this idea is Rwanda’s highly authoritarian President Paul Kagame, who has repeatedly argued that “Western” democracy is unsuited to the African context:

I’m not here to champion western anything … you forget my conditions here in Rwanda or in Africa that affect me daily in my life, and you are telling me I should be like somebody else. My starting point is to tell you, please put that aside.Footnote 4

Partly inspired by Kagame’s example and the economic success of China’s authoritarian government, the last decade has witnessed a growing number of African leaders and intellectuals pushing back against international calls for high quality elections, civil liberties, and human rights. During his prosecution for crimes against humanity, Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta coordinated governments from a number of different African states to reject the International Criminal Court, which he depicted as an unwarranted Western intrusion on African sovereignty, even though African states had played an important role in the Court’s formation (Shilaho Reference Shilaho2016). Similarly, long-time authoritarian leaders such as Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni and the late Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe have sought to delegitimate pro-democracy rivals by depicting those calling for political reform as agents of foreign powers. These critiques have been repeated by many high-profile commentators such as Andrew Mwenda, the owner of The Independent newsmagazine in Uganda, who has written about “The trouble with democracy in Africa.”Footnote 5

The durability of these narratives is closely linked to a tendency to overlook the role of domestic actors and protests in the process of political liberalization. It is easy to interpret the timing of the “third wave of democratization,” when the vast majority of African states reintroduced multiparty elections in the ten years that followed the end of the Cold War, as evidence that democratization occurred because the collapse of the Soviet Union freed up European and North American powers to focus on human rights rather than on security. Yet, although international pressure played a significant role in shifting the balance of power away from authoritarian leaders, this was never the main driver of political change.

For one thing, international support for democratization has actually been inconsistent, and has at times been undermined by the provision of military and anti-terror support for authoritarian leaders (Fisher & Anderson Reference Fisher and Anderson2015). For another, only in two cases did donors explicitly force African governments to hold elections by issuing an ultimatum—in Kenya and in Malawi—and even in these countries, donors were as much responding to pre-existing domestic calls for change as leading them. Moreover, Michael Bratton and Nicolas van de Walle (Reference Bratton and Walle1992) have documented the extent of mass protests in Africa during these years, and persuasively argued that it was predominantly domestic factors such as the strength of civil society and opposition mobilization that determined the extent and sustainability of democratic reforms.

The narrative that democracy in Africa was externally driven is therefore a-historical, and misleadingly elides African ownership of political change. In most cases, campaigns for the reintroduction of multi-party politics brought together remarkably diverse alliances of civil society groups, business leaders, trade unions, disgruntled politicians, and ordinary citizens. The popular protests these groups mobilized, such as the saba saba protests in Kenya and trade union strikes and mobilization in Zambia, did not emerge in a vacuum. Instead, they drew on the networks and narratives that had been developed to resist authoritarian rule in the 1970s and 1980s, when there was no Western democracy promotion to speak of (Sishuwa Reference Sishuwa2020). During these years, many writers, opposition leaders, journalists, trade unionists, religious figures, and ordinary citizens did not simply accept repressive government but often sought to resist it. In some cases, this resistance was explicit, as with Mwakenya, the underground socialist movement that emerged in Kenya in the 1980s, and sometimes subtle, as with the journalists who used satire to poke fun at those in power (Lungu Reference Lungu1986).

While it is true that democratic reforms were opportunistically supported by politicians who had fallen out of favor with the government and hoped to “recycle the elite” more than change the political system (Chabal & Daloz Reference Chabal and Daloz1999), opposing authoritarianism was not something to be done lightly. Pro-democracy activists risked beatings, torture, and death. Indeed, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that the strongest and most persuasive voices in favor of democracy have been African, not those of foreign leaders. These include Patrick Lumumba, the founding Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo; Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Nobel prize winner and former president of Liberia; and Levy Mwanawasa, Zambia’s late president, who denounced Zimbabwe’s 2008 elections as a “sham.”Footnote 6 Intellectuals such as Ken Saro-Wiwa, Wole Soyinka, and the late Chinua Achebe, all from Nigeria; Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Wangarĩ Maathai of Kenya, and many more, faced imprisonment and worse for criticizing authoritarian rule or for defending human rights.

Moreover, in stark contrast to the 1960s, many of the movements that emerged explicitly placed democratic values at the core of their appeal and indeed in their names: the United Democratic Front in South Africa, the Movement for Multiparty Democracy in Zambia, the Union for the Triumph of Democratic Renewal in Benin, and so on. The unity and fervor of these movements was not a Western product, but was instead rooted in the popular frustration with the broad-ranging failure of post-independence single-party and military regimes. With few exceptions, these political systems delivered disappointing levels of economic growth, weak infrastructure, poor quality public services, divided societies, and inefficient and predatory state structures (Kandeh Reference Kandeh1996). Although African governments faced many challenges not of their making, including problematic colonial legacies (Rodney Reference Rodney2018) and unfair terms of trade (Bond Reference Bond2006), the 1980s made it clear that the notion that “benevolent” dictators were best placed to develop the continent was badly misguided.

Despite this varied and strong evidence of the significance of popular mobilization to the collapse of authoritarian rule, the notion that democracy is alien to Africa continues to hold surprising traction. In addition to the fact that this narrative serves the interest of authoritarian leaders and ruling parties, one reason for this is the failure of many countries to establish stable and high-quality democracies (Adejumobi Reference Adejumobi2000). Almost every wave of elections has seen at least one case in which the combination of weak states, divided societies, and intense winner-takes-all competition generated significant political violence and instability (Olukoshi Reference Olukoshi1998). The early 1990s were overshadowed by the Rwandan genocide, which occurred during a process of supposed democratization that was scheduled to culminate in multiparty polls. The early 2000s saw electoral controversies contribute to the onset of civil war in Côte d’Ivoire, while the late 2000s witnessed electoral crises in Kenya (2007–08) and Zimbabwe (2008). At the same time as these high-profile conflicts, many countries have made precious little progress toward democratic consolidation, despite around thirty years having elapsed since the reintroduction of multiparty politics. According to Freedom House (2020), only 14 percent of African states are “free,” with 49 percent “partly free” and 37 percent “not free.”

This checkered progress has led to public and international concern and fed into an academic debate about the feasibility of democracy in Africa that has often reflected many of the concerns raised by Nyerere in the 1960s. The influential democracy scholar Claude Ake, for example, was highly critical of the abuse of power but also sympathetic to the argument that African societies are distinctive and therefore require different kinds of political systems. For Ake, the critical issue is that “Africans do not generally see themselves as self-regarding atomized beings in essentially competitive and potentially conflicting interaction with others” (Reference Ake1993:243). Political systems would therefore be more stable if they recognized and respected the centrality of ethnic identities and group identification in African societies. On this basis, Ake argues that “(d)emocracy has to be recreated in the context of the given realities and in political arrangements which fit the cultural context,” warning that if “African democracy follows the line of least resistance to Western liberalism, it will achieve only the democracy of alienation” (Reference Ake1993:244).

Ake was not alone in viewing African norms and values to run counter to liberal democracy. In a similar vein, George Ayittey (Reference Ayittey2006), a Ghanaian economist, suggests that Western style democracy “is possible but not suitable for Africa.” Still others have raised questions about the application of Western democratic theories (Mamdani Reference Mamdani1992), pointing out that domestic accountability is not feasible if the economic decisions of African governments are determined in advance by the ideological proclivities of international financial institutions (Mkandawire Reference Mkandawire and Joseph1999). In turn, such critiques fueled a distrust of democracy among those who, not unreasonably, came to associate it with the promotion of neo-liberal economic policies (Abrahamsen Reference Abrahamsen2000). It was a relatively small—though nonetheless flawed—intellectual leap to go from this kind of critical analysis of the “double transition” promoted by some Western governments and international financial institutions to the claim that African democratization had only come about because Western powers had decided to use political reform as a Trojan horse through which to open up African economies to greater exploitation.

Along with the rise of apparently successful “authoritarian-developmental” states in Ethiopia and Rwanda, these intellectual currents encouraged the revival of the old argument that tightly controlled political systems were better placed to deliver what Africa really needed: stability and development on its own terms (Booth & Golooba-Mutebi Reference Booth and Golooba-Mutebi2012). However, a deeper reading of many of these scholars provides support not for authoritarian rule, but rather for a stronger and “Africanized” version of democracy (Decker & Arrington Reference Decker and Arrington2015). For example, despite his concern that liberal democracy would impose a form of elitism on African political systems, Ake argued not for an authoritarian alternative but rather for the “the deepening of the democratic experience in every sphere” (Reference Ake2002:87), emphasizing the importance of accountability and human rights. At the same time, a number of researchers have demonstrated the feasibility of democracy by showing how a domestically driven democratization process in Somaliland fused traditional methods of resolving disputes with classic democratic institutions to develop an impressive “home grown” solution to political instability (Zierau Reference Zierau2003; Bradbury Reference Bradbury2008).

These nuances might have gained greater recognition were it not for broader shifts in the understanding of Africa and the lasting legacy of colonialism. From the mid-1990s onward, there has been growing criticism of the predominance of “Western” ideas, structures, and interests in African countries, and insistence on the need for “African solutions to African problems” (Ayittey Reference Ayittey2006). While many who have demanded “decolonization” have done so to further self-knowledge and mastery (wa Thiongʼo Reference wa Thiongʼo1986) and the quality of democracy, some strands of the movement have argued that challenging foreign political and economic domination requires questioning—and in some cases, rejecting—the “Western” preoccupation with human rights (Ibhawoh Reference Ibhawoh2008).

The growing assertiveness of African governments and intellectuals is undoubtedly a positive development, especially in light of continued global economic and knowledge inequalities, and the inconsistency—and at times outright hypocrisy—of European and North American governments, which claim to be committed to democracy but often sacrifice it for other goals (Imoedemhe Reference Imoedemhe2015). At the same time, however, this trend risks reinforcing the flawed notion that democracy and human rights are something that has been forced on the continent from outside. Against this, survey data reveals that democracy is highly valued by the vast majority of African citizens who, much like people around the world, wish to “assert their own agency” (Mwangi Reference Mwangi2014:94).

Popular Attitudes toward Democracy

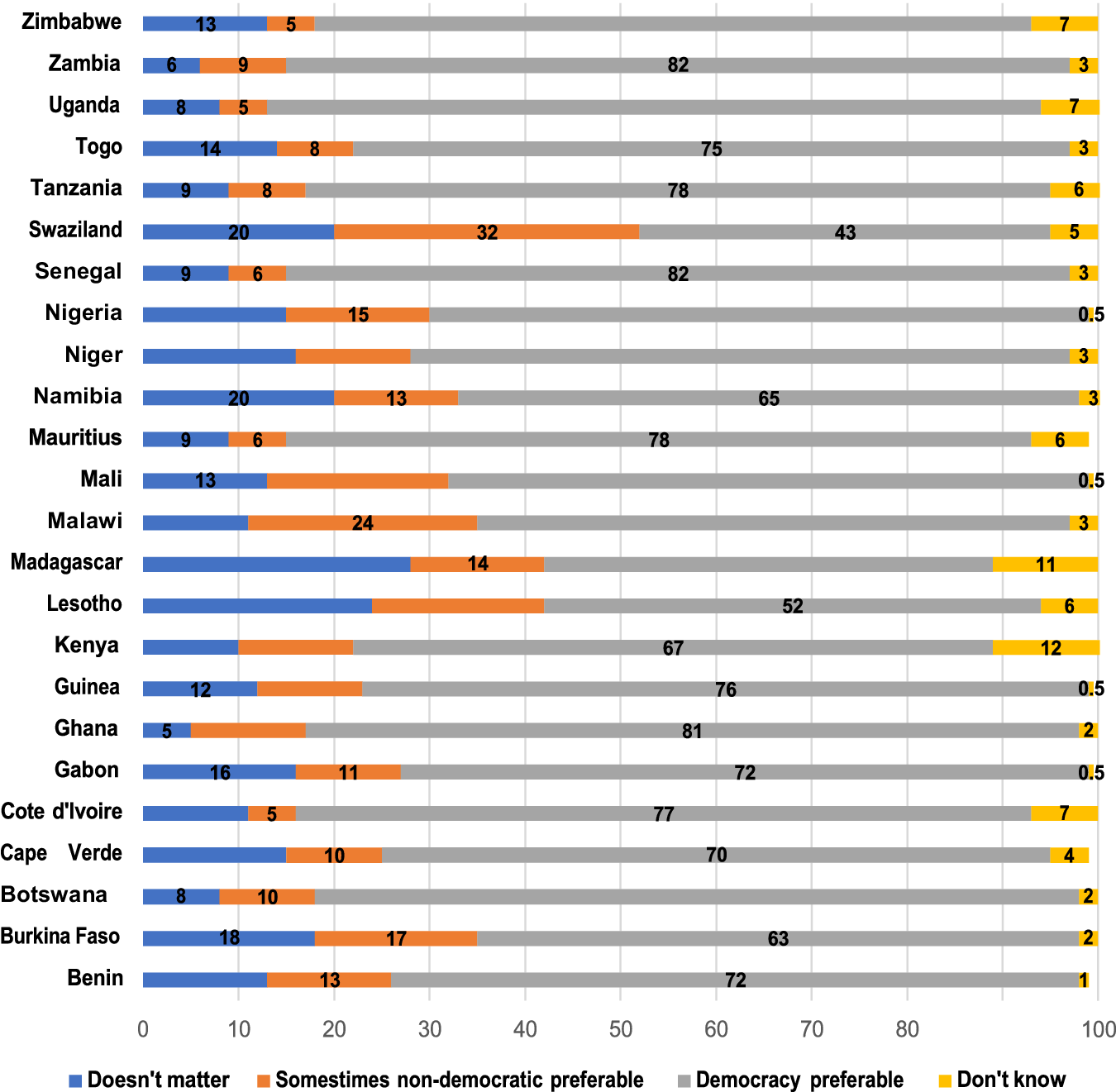

After years of living under unresponsive authoritarian governments that failed to engage meaningfully with their citizens, African societies demonstrate a strong desire to be able to choose their leaders. Nationally representative surveys carried out by the Afrobarometer group between 2016 and 2018 in thirty-five countries find that strong majorities prefer democracy to any other form of government in every state surveyed except for the small monarchy of eSwatini (Figure 1). It is important to note that the Afrobarometer sample does not include some of the most authoritarian states such as Rwanda and is therefore not fully representative. However, the survey does cover a number of highly authoritarian countries including Gabon, Togo, and Zimbabwe, and support for democracy tends to be high in these cases, usually exceeding 70 percent. Moreover, it is striking that only in two of the thirty-seven countries covered by the Afrobarometer do more than 20 percent of citizens believe that non-democratic political systems would be preferable: Malawi and eSwatini. Even in states in which the reintroduction of multiparty politics has been associated with political controversy and conflict, such as Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Togo, Uganda, and Zambia, more than three-quarters of citizens say that democracy is preferable.

Figure 1. Support for democracy in Africa 2016–2018 (%)

SOURCE: Afrobarometer (2019)

One reason that this strong popular support for democracy has not translated into a broader acceptance of the fact that democratic norms and values have become embedded in African societies is the popularity of the critique that survey respondents do not really know what “democracy” means, or that they understand the term in very distinctive and localized terms.Footnote 7 This suggestion is often made by urban elites, who are at times as skeptical of the knowledge and intellect of their rural counterparts as the colonial officials cited earlier. Andrew Mwenda has argued, for example, that “most Africans are ordinary uneducated peasants living in rural areas. They are not part of civil society; they belong to ‘traditional’ society.”Footnote 8 In line with this argument, it is often suggested that African societies mainly favored democracy because they believed that moving to a Western model of government would resolve their economic difficulties, and so would be happy to trade democracy off against development if it could be better realized by another system of government.

Early analysis of the Afrobarometer data provided some initial support for this position. In the early 2000s, large majorities agreed that the provision of “basic necessities like shelter, food and water” (90 percent), “jobs for everyone” (86 percent), “equal access to education” (88 percent), a “small income gap” (73 percent) were important for a country to be called a democracy. More broadly, Bratton finds that when encouraged to think about the delivery of socio-economic goods, interviewees broaden “their initial conception of democracy to include positive (social and economic) as well as negative (civil and political) rights” (Bratton Reference Bratton2002:6).

Properly understood, however, these findings do not suggest that African societies only value democracy for instrumental reasons. While citizens’ satisfaction with democracy is shaped by the delivery of economic goods in addition to the provision of political rights (Bratton & Mattes Reference Bratton and Mattes2001), the “initial conception of democracy” that Bratton mentions reveals a fairly “classic” understanding of democracy, with a heavy emphasis on representative government, checks and balances, and civil liberties. When asked to define democracy in an open-ended question, most respondents referred to elections or a form of representative government. “Perhaps unexpectedly,” one third of respondents provided “universal and liberal definitions, associating democracy with civil liberties (28 percent), notably freedom of expression, and with political rights (8 percent)” (Bratton Reference Bratton2002:4). The fact that liberties and political freedoms were the most common answer, followed closely by “government of the people” (20 percent) and “voting and elections” (9 percent), suggests that African societies have a strong commitment to procedural democracy and are not only interested in what their political system can deliver.

Although the Afrobarometer is regularly praised for having some of the most rigorous procedures of the various regional “barometers” (Heath et al. Reference Heath, Fisher and Smith2005), skeptics often level a second criticism at its findings, namely that individuals give the “right” answer rather than the real one to questions about democracy. In other words, knowing that researchers are likely to support democracy, respondents give them what they want. This is a valid concern, because recent research has found that participants sometimes change their behavior when a foreign researcher is present in line with what they think the researcher wants to hear (Cilliers et al. Reference Cilliers, Dube and Siddiqi2015).

There are good reasons for thinking that this criticism is wide of the mark where the Afrobarometer is concerned, however. First, respondents typically demonstrate a strong commitment to democratic values in questions where there is less obviously a “correct” answer. The survey generally finds overwhelming support for presidential term limits (Dulani Reference Dulani2015), for example, which is an issue on which there has been less effort to sensitize voters (Cheeseman et al. Reference Cheeseman, Lynch and Willis2020:Ch 6). Moreover, African societies typically reject the idea of concentrating vast powers on the president, even when “democracy” is not mentioned.

Second, the continent regularly sees public demonstrations of the commitment of large numbers of citizens to democratic values—or at the very least of a rejection of authoritarianism—in the form of mass protests. Adam Branch and Zachariah Mampilly (Reference Branch and Mampilly2015) argue that the failure of African governments to democratize has driven a new wave of popular protest in countries such as Uganda, Nigeria, Senegal, and Sudan. Similarly, Lisa Mueller (Reference Mueller2018) has documented an “explosion of protest and social movements” in twenty-first century Africa, arguing that these are driven by the efforts of the middle class to “launch movements for democratic renewal” to secure greater access to resources and political autonomy, and the “material” concerns and “political grievances” of “lower classes.” Significantly, these protests are not mere symbolic gestures; in countries such as Burkina Faso, Malawi, and Sudan, public uprisings have played an important role in either securing democratic reform or forcing authoritarian leaders from power.

Third, a range of more historical and anthropological studies have demonstrated how multiparty elections have been “domesticated” and embedded within everyday political practices (Cheeseman et al. Reference Cheeseman, Lynch and Willis2020:173). In addition to high levels of intrinsic support for democracy, multiparty elections are valued because they have become enmeshed in local conversations about the distribution of power and resources in a way that had great meaning for those who participated in them. Writing about Kenya, Ghana, and Uganda, (Willis et al. Reference Willis, Lynch and Cheeseman2018:1113) argue that elections matter to citizens not only because they represent an opportunity to demand more from the government—and in some cases to receive handouts of cash and gifts—but also because they are bound up with important questions such as how resources should be distributed and how leaders should behave. Thus, one reason that political participation remains high in many countries in which elections rarely lead to a transfer of power is that “campaigns create an opportunity to make claims and advance moral projects that genuinely matter to people at multiple levels of the political and social system” (Cheeseman et al. Reference Cheeseman, Lynch and Willis2020:9). Significantly, research has shown that elections can have this effect even when they are relatively poor quality (Harding Reference Harding2020).

It should therefore be clear that support for democracy is not simply a fleeting pretence that individuals put on whenever researchers are in town, but a considered preference. Indeed, it is the combination of pro-democratic attitudes and the embedded nature of electoral processes that explains why holding elections has come to be central to political legitimacy in so many African countries (Throup Reference Throup1993).

Consensual Democracy: Maintaining Unity amid Competition

The strong support shown for democracy as a system of government does not mean that African societies have uncritically adopted a “Western” mindset. As Mikael Karlström (Reference Karlström1996:500) has argued, the way that a society interprets democracy must be “understood with reference to an existing socio-political cosmology.” Few researchers have taken up this task as rigorously as Frederick Schaffer, whose study of what democracy means to different communities in Senegal contrasts how the French-speaking elite deploy démocratie with the multiple meanings that demokaraasi has for Wolof speakers. In doing so, he demonstrates how démocratie may be taken to mean both democratic institutional arrangements and the authority of the people, and how demokaraasi may variously be used to emphasize consensus, competition, community solidarity, and an equal share of resources. Through these examples, he reveals that the “projections and metaphors” used alongside terms for democracy “carry with them meanings embedded in popular culture” that pull them from their “semantic foundation” (Reference Schaffer2000:52). It is beyond the scope of this analysis to investigate political language in this depth, but it is feasible to investigate whether there are any distinctive patterns in popular understandings of democracy in sub-Saharan Africa.

Over the past forty years, a growing literature has sought to compare political values and attitudes toward democracy cross-regionally. Ronald Inglehart maps “global values” along two dimensions: whether societies hold more “secular” or “traditional” values, and whether they prioritize “survival” or “self-expression” (Reference Inglehart2006:122). The central intuition underpinning this approach is that while “the desire for freedom is a universal human aspiration, it does not take top priority when people grow up with the feeling that survival is uncertain” (Reference Inglehart2006:115). Using data from the World Values Survey, Inglehart argues that Asian societies are largely “secular” and place a premium on “survival,” while “English origin” societies are comparatively less committed to a “secular” worldview and are more likely to prioritize “self-expression.” For their part, African societies are said to prioritize “traditional” values and “survival.” On this basis, he suggests that self-expression values are driven by “economic development, with the value systems of rich countries differing systematically from those of poor countries” (Reference Inglehart2006:122).

Inglehart’s argument reflects a broader consensus that “English origin” societies value liberty above order, in part because rising standards of living have freed them to invest in “post-materialist” values, which emphasize self-expression and quality of life over physical and economic security (Dalton Reference Dalton2013; Bernhagen & Marsh Reference Bernhagen and Marsh2007). By contrast, Asian societies are often said to emphasize order ahead of liberty—in part because they also feature greater deference to authority (Park & Shin Reference Park and Shin2006; Zhai Reference Zhai2017), although the extent to which this represents a distinctive set of “Asian values” remains controversial (Thompson Reference Thompson2001; Kim Reference Kim2010). Inglehart’s argument implies that we should expect a similar finding where sub-Saharan Africa is concerned.

In reality, however, most African societies are reluctant to trade off freedom for security, and so are more “post-materialist” where democracy is concerned than their level of socio-economic development would suggest.Footnote 9 This is not to say that concerns over unity and order are not present—they are, shaped by the debates and narratives documented in this article—but they do not override a commitment to representative government. Instead, a careful reading of the Afrobarometer data suggests that most societies seek a form of consensual democracy that places limits on the extent of political competition, but without compromising the principle of political accountability.

More specifically, consensual democracy has four main features. The first is a strong support for selecting the government through multi-party elections. Three-quarters of those surveyed across Africa between 2016 and 2018 agreed with the statement “We should choose our leaders in this country through regular, open and honest elections,” and almost 65 percent also agreed with the statement “Many political parties are needed to make sure that [the people] have real choices in who governs them.”

The second main feature is a commitment to political accountability and, in line with this, to certain critical checks and balances. While overwhelming majorities support upholding the rule of law, over three quarters of respondents also agreed with the statement “The Constitution should limit the president to serving a maximum of two terms in office.” Contrary to the widespread perception that Africans are willing to sacrifice democracy on the altar of development, only 34 percent of respondents agree that it is more important to have a government that gets things done than it is for the government to be accountable to the citizenry.Footnote 10

The third main feature of consensual democracy is a desire for basic freedoms. Over three quarters (76 percent) agree that a citizen’s freedom to criticize the government is “important” or “essential” for a society to be called democratic (Afrobarometer 2003), and responses to the 2016–18 surveys reveal that over 60 percent of individuals believe that they “should be able to join any organization, whether or not the government approves of it.” The fact that a significant minority were willing to support the right of the government to determine the kinds of organizations that can be joined hints at the fourth feature of consensual democracy: a concern to prevent “excessive” freedom and competition lest it lead to disunity and instability.

The fourth main component of this belief system is therefore strong support for a consensual form of politics in which parties put aside their difference and work for the common good. One reason for this is that a majority (55 percent) of people believe that competition between political parties “always” or “often” leads to violent conflict. Another is that decades of being socialized into hierarchical political systems, combined with the tendency of the media to be more critical of the opposition than of the government, means that there is a significant trust gap between those who hold power and those who do not. While a majority of citizens report trust in the president and 44 percent in the ruling party, the opposition is only trusted by 36 percent, while 34 percent report “no trust at all.”

This concern to maintain unity manifests itself in a strong preference for less confrontational political strategies, for example in the settling of disputes. In Uganda, fully 81 percent of respondents agreed with the statement “Losing parties should accept the elections results” in 2018, even though only 34 percent thought the elections were “completely free and fair.” Moreover, when it comes to threats to national unity and security, a majority of citizens support the right of the government “to prevent the media from publishing things that it considers harmful to society.” One of the main vulnerabilities of consensual democracy is therefore that leaders who can persuade citizens that their country faces a grave risk of instability may be able to legitimate democratic backsliding.

This possibility is particularly significant in light of the fact that the Afrobarometer has consistently found that while a strong majority of Africans reject two or three types of authoritarian rule—military, one-man, one-party, and traditional rule—only around half of respondents reject all four. In turn, this has led Bratton (Reference Bratton2002:3) and others to question the depth of support for democracy in Africa. It is therefore particularly significant that the Afrobarometer records falling support for media freedoms between 2011 and 2018 (Conroy-Krutz & Appiah-Nyamekye Sanny Reference Conroy-Krutz and Sanny2019), driven in part by growing public concern about “fake news” and its potentially divisive and destabilizing effects (Cheeseman et al. Reference Cheeseman, Fisher, Hassan and Hitchin2019). But while attitudes toward democracy are constantly evolving in response to lived experience, African societies continue to be reluctant to trade in rights and liberties for stability and economic benefits. When asked whether the government should be allowed to monitor private communications in case people are plotting violence, an absolute majority (53 percent) of respondents disagreed, stating that “People should have the right to communicate in private without a government agency reading or listening to what they are saying.” Moreover, when democratic institutions and norms are threatened, popular support for them tends to increase. For example, public support for presidential term limits rose in Burundi during President Pierre Nkurunziza’s effort to force an unconstitutional third term in power (Dulani Reference Dulani2015). Support for democracy may be vulnerable to long-term erosion, then, but it is unlikely to simply collapse.

There are, of course, considerable variations in popular attitudes across the continent, and indeed within individual countries (Cheeseman et al. Reference Cheeseman, Lynch and Willis2020). In line with the variation in the support for democracy described above, respondents in eSwatini, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, and Mozambique were less fervent in their commitment to selecting governments through elections, although only in Lesotho did this drop below 50 percent. Somewhat surprisingly, support for elections was also below average in South Africa, perhaps because ANC dominance has demonstrated that elections may play little role in changing the composition of the government. Popular commitment to free speech has tended to be particularly high in Botswana (85 percent) and Nigeria (83 percent) and lower in Lesotho (52 percent) and Namibia (67 percent), although this still represents a strong majority in the Namibian case. Support for holding the government accountable even at the cost of “getting things done” also varies; perhaps because the vast majority of the population support the ruling party, Namibians and South Africans are more likely than others to prioritize efficiency.

Yet, for all of these important variations, one of the most striking things about attitudes toward democracy in Africa is the extent to which the broad foundations of consensual democracy hold true across almost all states. In every country surveyed, a majority of people favor using multiparty elections to choose the government, but also believe—with the sole exception of Mauritius, which has enjoyed vibrant multiparty politics since independence—that “once an election is over, opposition parties and politicians should accept defeat and cooperate with government.”Footnote 11

Conclusion: The Troubled History of an Idea

The term “democracy” has a long and complicated history in sub-Saharan Africa. Although nationalist movements fought for freedom and “liberation,” they did not always frame these demands in the language of democratic norms and values. In the 1960s, the collapse of multi-party political systems in countries such as the DRC and Nigeria, and the connection that was quickly drawn between political competition and ethnic-conflict, provided ammunition for those who wished to argue that the continent needed unity more than freedom. Events in the 1990s, such as the Rwanda genocide and the election-related violence in countries such as Côte d’Ivoire and Kenya, played into these tropes.

The legacy of these narratives runs deep. Even after nearly three decades of multi-party politics, most African societies demonstrate particularly high levels of trust in the president and low levels of trust in opposition parties. Yet, we have argued that this antipathy toward political disagreement has not led to a rejection of democracy, but rather given rise to a strong public preference for a form of consensual democracy that balances the desire for representative government against the concern for unity. This position deserves to be treated as a serious set of considered beliefs and cannot be dismissed on the basis that African citizens do not know what democracy means, or that they have been duped by Western powers. Indeed, the notion that democracy has been imposed by outside forces is in part a creation of authoritarian leaders designed to make it easier for them to retain political control.

The enduring commitment to democracy in so much of the continent is rooted in two main factors. The first is that people in Africa, like people around the world, value having a say in the decisions that affect their own lives. This helps to explain why so many governments have sought to secure a degree of democratic legitimacy, even when their power has rested on repressive foundations. Second, and relatedly, democracy—and more specifically multi-party elections—have provided an arena in which individuals and communities can debate what it means to be a good leader and make claims on those in power. That these demands have often gone unmet has done little to dampen the fervor with which they are made, and as a result, elections have become embedded as a central part of the political landscape. Taken together, these factors mean that popular engagement with democracy remains high, despite the setbacks of the 1990s.

In many countries, these underlying preferences for more inclusive forms of government have interacted with, and been shaped by, changes in the dissemination of information and the dynamics of political communication. As Nanjala Nyabola has written, the advent of social media has encouraged greater popular participation in “digital democracy” (Reference Nyabola2018). While the “analog politics” of the past continues to generate challenges for democratic consolidation, the possibility of mobilizing opinion and holding those in power to account online has enabled individuals to “reclaim the agency to shape their own stories” (deSouza Reference deSouza2018). Governments in countries such as Chad, DRC, Ethiopia, Gabon, Sudan, and Zimbabwe have responded by seeking to blunt the power of social media, in some cases by simply shutting down the Internet. But while this is often effective in the short term, it has also encouraged stronger demands for freedom of expression among those whose voices have been silenced.

The vibrancy of popular engagement with democracy is not a reason for complacency, however. Public frustration with poor quality elections and falling satisfaction with democracy as it is playing out in practice have led to a decline in support for selecting leaders through elections since 2015 (Bratton & Bhoojedhur Reference Bratton and Bhoojedhur2019). It is therefore significant that many elections are problematic and controversial, which increases the risk of political instability and violence while undermining accountability (Cheeseman & Klaas Reference Cheeseman and Klaas2019). According to one recent study, the proportion of Africans who say that elections are “effective in ensuring that representatives … reflect the views of voters” has fallen to just 42 percent in recent years (M’Cormack-Hale & Zupork Dome Reference M’Cormack-Hale and Dome2021). If elections do not allow for political change while at the same time generating considerable instability, citizens are likely to lose confidence that substantive democracy can be realized, and so lose faith in its procedural foundations.

At the same time, if more individuals come to believe that contrary to the comparative data on the continent, the economic success of Rwanda—and beyond Africa, the rise of China—means that competitive elections are actually a hindrance to development, they may become more sympathetic to authoritarian models of government. If both these trends continue, support for democracy is unlikely to collapse, but may nonetheless fall low enough for incumbents to calculate that they can undermine democratic norms and values without harming their popularity. As in the 1960s, basic political freedoms are at their most vulnerable when they are seen to be in tension with the achievement of unity and development.