Introduction

Neolithic circular enclosures, or ‘rondels’, are considered to be one of the earliest forms of monumental architecture in Central Europe, first appearing c. 4800 BC (Kovárník et al. Reference Kovárník, Květ and Podborský2006; Literski & Nebelsick Reference Literski, Nebelsick, Bertemes and Meller2012; Řídký et al. Reference Řídký, Květina, Limburský, Končelová, Burgert and Šumberová2018). These enclosures were defined by concentric ditches, banks and timber palisades. Despite some variation in the size of each rondel and in the numbers of ditches, palisades and entrances, their overall similarity of layout and form suggests the existence of a set of shared inter-community norms, ideas and beliefs, probably related to social integration and the expression of identity. Notably, these shared ideas as manifested through rondel building extended beyond regional differences expressed in other forms of material culture, such as ceramics (Literski & Nebelsick Reference Literski, Nebelsick, Bertemes and Meller2012).

Until recently, it was widely believed that rondels were characteristic of the Danubian zone with only an incidental presence north of the Carpathian and Sudeten Mountains in the territory of modern-day Poland. This view was based on cultural-historical assumptions about a ‘core’ or ‘centre’ of Neolithic innovation in the Danube basin and the limited and delayed transmission of cultural developments to peripheral regions (e.g. Kulczycka-Leciejewiczowa Reference Kulczycka-Leciejewiczowa and Hensel1979).

The first indications that rondels might extend north of the Carpathian and Sudeten Mountains emerged as a result of the wider adoption of aerial prospection in Polish archaeology. Aerial photographs taken by Otto Braasch in 1998 and by Włodzimierz Rączkowski in 2008 led to the identification of two rondel enclosures: at Bodzów (Lower Silesia; Kobyliński et al. Reference Kobyliński, Braasch, Herbich, Misiewicz, Nebelsick and Wach2012) and at Wenecja in the north-east Wielkopolska region (Rączkowski Reference Rączkowski and Sawicki2009). The discovery of these two sites raised the question of whether the absence or rarity of Neolithic rondel structures north of the Carpathians and Sudeten Mountains was potentially an artefact of the prospection methods traditionally applied in this region (e.g. fieldwalking; see Nowakowski & Rączkowski Reference Nowakowski and Rączkowski2000). Notably, in other parts of Central Europe such as Austria and Slovakia, the application of novel prospecting techniques has resulted in numerous new discoveries of prehistoric enclosures (e.g. Trnka Reference Trnka1991; Podborský Reference Podborský1999; Kovárník Reference Kovárník and Čižmář2008; Melichar & Neubauer Reference Melichar and Neubauer2010; Kuzma & Tirpák Reference Kuzma, Tirpák, Bertemes and Meller2012; Valera Reference Valera and Gibson2012). We therefore instigated a systematic programme of aerial prospection methods in south-west Poland to assess whether further rondels could be detected in Lower Silesia, bridging the apparent gap in the distribution of these enclosures between the two recently discovered rondels at Bodzów and Wenecja and the region of Bohemia and Moravia (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of Central Europe with location of Neolithic rondel enclosures (red squares) within the Lower Silesia study area (black outline) and other known rondel enclosures in Europe (red circles) (after Kravciv Reference Kravciv2019; figure by authors).

In this article, we report and assess the results of this fieldwork and consider whether our current knowledge of rondels accurately documents the extent of their past distribution or, rather, reflects uneven archaeological attention. Further, we ask, if rondels, or rondel-like structures, are found to extend consistently beyond the ‘core zone’, how would this change narratives about early European farming communities more broadly?

Early farming communities in the ‘age of rondels’

Starting in the sixth millennium BC and extending across a wide swathe of Central Europe, the Early Neolithic Linearbandkeramik (LBK) culture was characterised by broadly homogeneous settlement forms, material culture and socio-economic organisation. The emergence of regional pottery styles in the early fifth millennium BC allows archaeologists to single out distinct groups; for example, the Lengyel culture and the Stichbandkeramik (Stroke Ornamented Ware/SBK) culture. These new ceramics styles are taken to represent more fundamental social, economic and ideological change (Czerniak Reference Czerniak, Gleser and Becker2012; Hofmann & Gleser Reference Hofmann, Gleser, Gleser and Hofmann2019).

New distinct types of pottery also appeared north of the Carpathian and Sudeten Mountains, in south-west Poland. It is sometimes assumed that these developments were the result of a combination of existing regional traditions and the arrival of new ideas from the south, moving through interregional networks (Czerniak Reference Czerniak, Gleser and Becker2012). From a cultural-historical perspective, these northern communities are therefore relegated to a peripheral status in relation to the Danubian heartlands and defined by the late and selective adaptation of the social and economic developments originating in the latter (e.g. Kulczycka-Leciejewiczowa Reference Kulczycka-Leciejewiczowa and Hensel1979). A particular point of difference to the north and south of the Carpathian and Sudeten Mountains concerns rondels. With nearly 200 rondels and rondel-like features recognised along the Danube and its tributaries, these enclosures are a defining feature of the ‘cultural centre’ (Figure 1). In contrast, their absence or rarity north of the Carpathian and Sudeten Mountains appears to support the idea that this was a peripheral region, only partially engaged in the full cultural package of the Danubian core (Literski & Nebelsick Reference Literski, Nebelsick, Bertemes and Meller2012). It is increasingly evident, however, that the absence or scarcity of rondel sites in south-west Poland is a result of the choice of archaeological prospection methods employed (see Polish Archaeological Record, e.g. Jaskanis Reference Jaskanis and Larsen1992; Rączkowski Reference Rączkowski, Brophy and Cowley2005, Reference Rączkowski and Cowley2011). Here, we demonstrate how a new methodological approach can both identify new sites and contribute to a rethinking of ideas about the apparently peripheral status of this region and the wider nature of cultural change in fifth-millennium BC Central Europe.

Methods

We developed an integrated non-invasive survey approach combining satellite imagery, aerial photography, airborne laser scanning and magnetic gradiometry (Table 1). This approach allowed for spatial analysis on two levels: the individual archaeological site and at the wider landscape scale.

Table 1. Sources of archaeological mapping data for sites included in this study.

Note: the numbers given in Column 1 refer to descriptions given in the caption of Figure 10.

Applied open data: includes interpretation of satellite images in our mapping of the features.

Not visible: means that no crop marks were visible on the available open satellite imagery and this not used in the mapping process.

We started with regional-scale aerial prospection from a light aircraft, supplemented by unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) flights (Musson et al. Reference Musson, Palmer and Campana2013; Gojda Reference Gojda2020; Figure 2). Images of cropmarks and soilmarks were captured digitally using DSLR handheld cameras connected to a GPS for geolocation. We also used open remote-sensing Earth-observation data accessible via services such as Google Earth (Luo et al. Reference Luo2018); we have particularly benefitted from the release of high-resolution data since 2015. In addition, we used airborne laser scanning for high-resolution topographic analysis (Kovárník & Mangel Reference Kovárník, Mangel, Cheben and Soják2013). Data from Poland's nationwide Airborne Laser Scanning project (Kurczyński Reference Kurczyński2019) were used to create digital elevation models and derivatives, including hillshading, sky-view factor, simple local relief models and slope (Štular et al. Reference Štular, Kokalj, Oštir and Nuninger2012).

Figure 2. Research methods: A) aerial surveys; B) magnetic gradiometry surveys; C) archival and desk-based assessment; D) aerial survey flight tracks 2012–21 with location of rondel and enclosure features: 1) Sieroszów A; 2) Sieroszów B; 3) Piotrowice Polskie; 4) Księginice Małe A; 5) Księginice Małe B; 6) Gniechowice; 7) Drzemlikowice; 8) Zabardowice; 9) Proszkowice; 10) Bodzów; 11) Drzemlikowice ovaloid enclosure; 12) Księginice Małe circular enclosure; 13) Drzemlikowice small enclosure (figure prepared by authors).

Based on results achieved at the regional level, individual sites were then selected for geophysical survey. Most of these surveys used magnetic gradiometry (Aitken et al. Reference Aitken, Webster and Rees1958; Aspinall et al. Reference Aspinall, Schmidt and Gaffney2008; Figure 2B), deploying multi-sensor handheld instruments (Bartington GRAD 601-2) and GPS-integrated cart systems (Sensys MXPDA). We typically sampled at 1 × 0.25m, using 0.5 × 0.1m for a few specific contexts. Newly collected data were then compared with any published or archive data from excavations and fieldwalking (including the Polish Archaeological Record, or AZP; Figure 2C).

Results

Using the results of our large-scale aerial surveys, as well as desk-based assessment of satellite imagery and orthophotos, we identified eight new Neolithic circular rondel enclosures (Figures 1, 2 & 10). These eight features have then been mapped using a combination of data sources (Table 1) to determine their spatial and morphological characteristics (Table 2). Two previously identified sites are also included in our overview: Bodzów, mentioned above (Kobyliński et al. Reference Kobyliński, Braasch, Herbich, Misiewicz, Nebelsick and Wach2012; Welc et al. Reference Welc, Nebelsick and Wach2019; Figure 3), and Proszkowice, discovered in 2012 by the ArchaeoLandscape Europe project (http://www.arcland.eu/; Figure 4). Both were identified during ad-hoc aerial prospection over a period of 14 years. The eight new sites, plus several associated features described below, were documented over a five-year period (2017–2021) as part of our planned surveys and desk-based assessment of satellite imagery.

Table 2. Morphology of recognised features: aerial photography (AP); magnetic gradiometry (MA); desk based remote sensing assessment (DBRSA); excavations (EXC).

Note: the numbers given in Column 1 refer to descriptions given in the caption of Figure 10.

Figure 3. Bodzów: left) mapping of rondel enclosure based on available data; A) aerial imagery, 06.2017, geoportal.gov.pl; B) aerial imagery, 07.2010, geoportal.gov.pl (figure prepared by authors).

Figure 4. Proszkowice: left) mapping of rondel enclosure based on available data; A) aerial photography, 11.07.2015, by W. Rączkowski; B) satellite imagery, 06.2017, Maxar Technologies, Google Earth; C) aerial imagery, 05.2017, geoportal.gov.pl; D) satellite imagery, 07.2015, Maxar Technologies, Google Earth (figure prepared by authors).

Aerial photographs and remote-sensing imagery typically show concentric ditch systems, but do not always provide a clear picture of associated features. Photographs taken in July 2018 of the rondel at Drzemlikowice demonstrate the details that can be detected under the right circumstances. Figure 5E shows an arrangement of three concentric palisades and LBK longhouses, as well as other structures, including two potential henges or tumuli dated to the Eneolithic or Early Bronze Age, based on the available data from aerial imagery and geophysical surveys (for similar features, see Ch'ng et al. Reference Ch'ng, Chapman, Gaffney, Murgatroyd, Gaffney and Neubauer2011).

Figure 5. Drzemlikowice complex: left) mapping of features based on available data; A) satellite imagery, 06.2018, Maxar Technologies, Google Earth; B) satellite imagery, 06.2018, Maxar Technologies, Google Earth; C) satellite imagery, 06.2018, Maxar Technologies, Google Earth; D) aerial photography, 13.07.2017, by P. Wroniecki; E) aerial photography, 22.06.2018, by P. Wroniecki; F) aerial photography, 12.07.2021, by P. Wroniecki; G) aerial photography, 28.06.2019, by P. Wroniecki; H) magnetic gradiometry survey; I) aerial photography, 22.06.2018, by P. Wroniecki (figure prepared by authors).

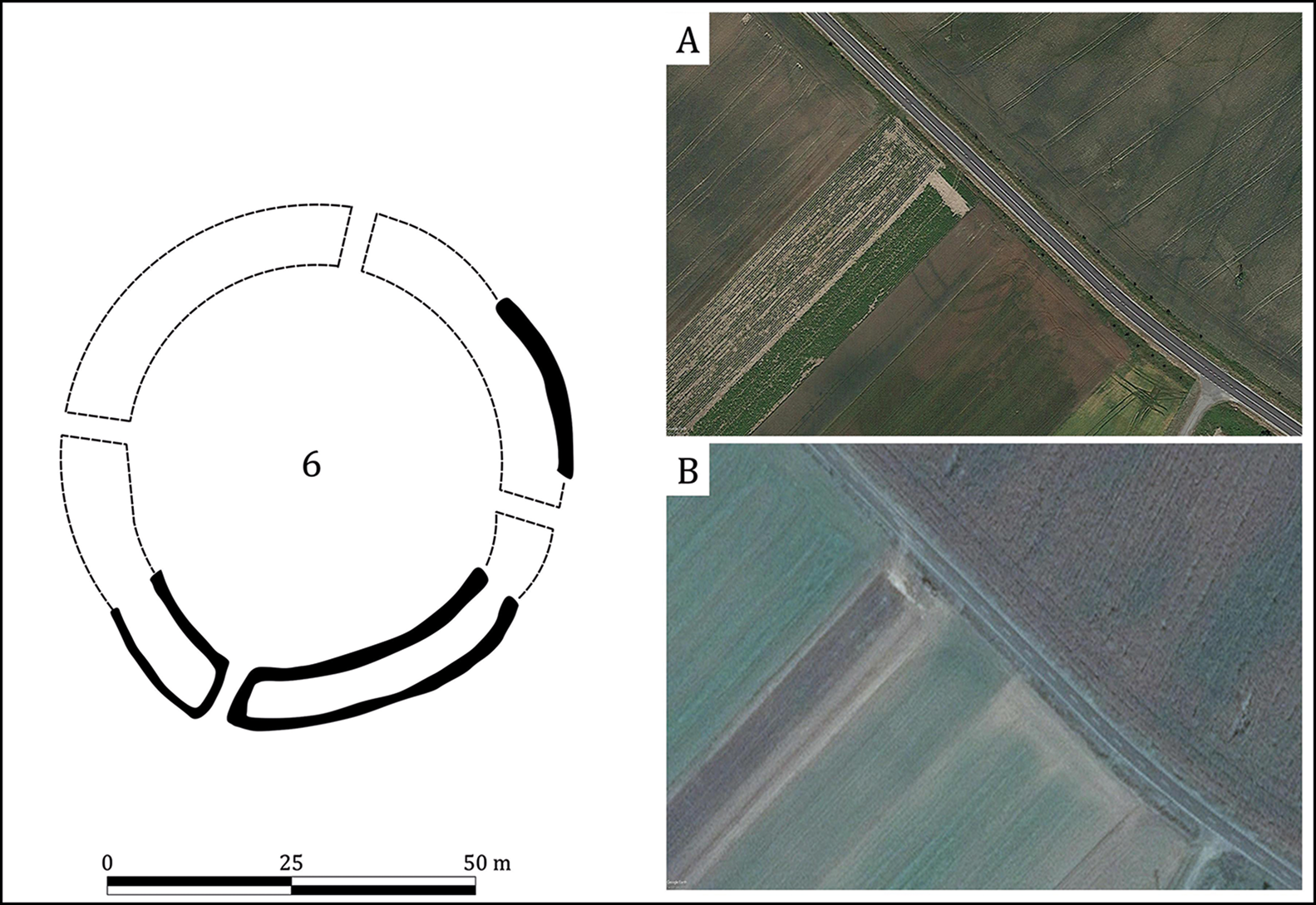

The conditions necessary for the formation of various crop and soil anomalies are, however, not always as favourable as at Drzemlikowice. More frequently, despite the abundance of remote-sensing and geophysical data, we encountered difficulties in the detailed interpretation of individual rondels. This is exemplified by the rondel at Zabardowice, which is only partially legible in the aerial photographs (Figure 6A–C) and magnetic gradiometry data (Figure 6D), limiting the determination of the site's precise layout. Similar issues were encountered at most of the detected sites, including Księginice Małe (Figure 7) and Gniechowice (Figure 8).

Figure 6. Zabardowice: left) mapping of rondel enclosure based on available data; A) aerial photography, 16.07.2019, by P. Wroniecki; B) aerial photography, 16.07.2019, by P. Wroniecki; C) aerial imagery, 06.2016, geoportal.gov.pl; D) magnetic gradiometry survey (figure prepared by authors).

Figure 7. Księginice Małe complex: left) mapping of features based on available data; A) aerial photography, 12.07.2021; B) aerial photography, 12.07.2021; C) aerial photography, 12.07.2021; D) aerial photography, 16.07.2019; E) aerial photography, 12.07.2021; F) satellite imagery, 07.2015, Maxar Technologies, Google Earth (aerial photography for A–E by P. Wroniecki; figure prepared by authors).

Figure 8. Gniechowice: left) mapping of rondel enclosure based on available data; A) satellite imagery, 06.2018; B) satellite imagery, 09.2016 (photographic images by Maxar Technologies, Google Earth; figure prepared by authors).

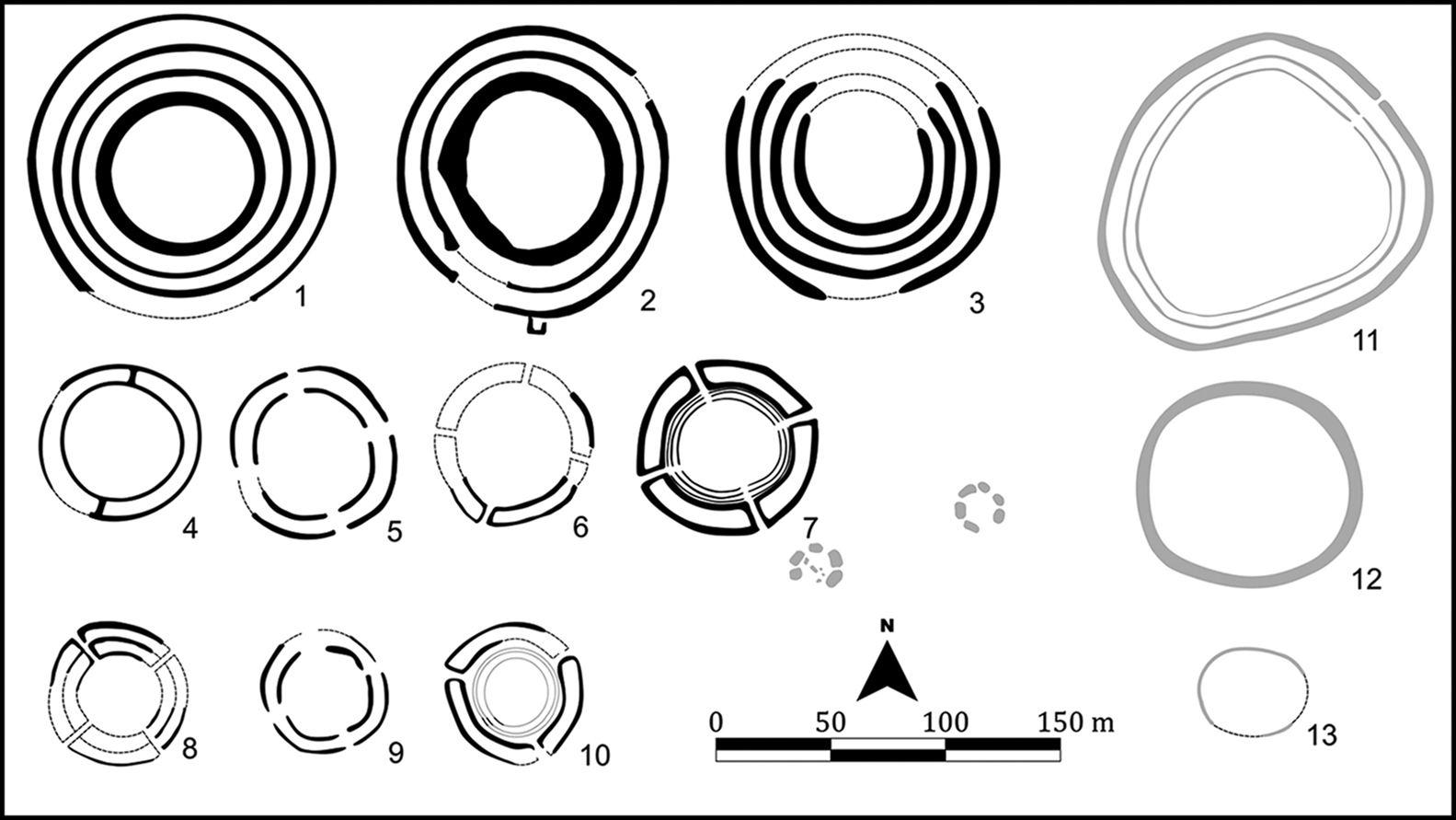

The eight sites identified in Lower Silesia, like those found elsewhere, are not identical and represent several variants within the wider morphological canon of Neolithic rondels. Most of these sites are medium-sized, with diameters ranging from 55 to 80m (Figures 3–8), though the structures from Sieroszów (A and B) and Piotrowice Polskie (Figure 9) stand out, with diameters ranging from 115 to 135m. The rondels also demonstrate some variation in orientation and the numbers of ditches and entrances (Table 2, Figure 10).

Figure 9. Sieroszów-Piotrowice Polskie complex: left) mapping of features based on available data; A) satellite imagery, 12.2019; B) satellite imagery, 02.2019; C) satellite imagery, 08.2018; D) satellite imagery, 12.2019; E) satellite imagery, 02.2019; F) satellite imagery, 07.2015; G) satellite imagery, 09.2019, CNES/Airbus, Google Earth; H) satellite imagery, 10.2017; I) satellite imagery, 10.2010 (photographic images A–F, H & I by Maxar Technologies, Google Earth; figure prepared by authors).

Figure 10. Morphology of rondel enclosures based on non-invasive mapping. Filled outlines represent aerial and geophysical anomalies; dashed lines present hypothetical or presumed continuations of features. Grey-filled outlines present features within complexes of rondel enclosures; 1) Sieroszów A; 2) Sieroszów B; 3) Piotrowice Polskie; 4) Księginice Małe A; 5) Księginice Małe B; 6) Gniechowice; 7) Drzemlikowice Neolithic rondel along and two possible henge features; 8) Zabardowice; 9) Proszkowice; 10) Bodzów; 11) Drzemlikowice ovaloid enclosure; 12) Księginice Małe oval enclosure; 13) Drzemlikowice small enclosure (figure prepared by authors).

The primary defining element of all the sites is the presence of concentric ditches. In our dataset, sites typically have two ditches (Figures 3–5 & 7–8), but there are three ditches at Zabardowice (Figure 6) and Sieroszów B (Figure 9D–F), and four ditches at Sieroszów A (Figure 9A–C) and Piotrowice Polskie (Figure 9G–I). Timber palisades were almost certainly present at all these sites, but direct evidence is only available from the excavations in Bodzów (Figure 3) and from aerial and magnetic prospection at Drzemlikowice (Figure 5A, D–F & H). The number of entrances through the concentric ditches into the interior space can be defined for only some of the sites. The most common number of entrances is four, and less frequently, three (Table 2).

The newly discovered rondels are predominantly found in isolation from evidence for other types of landscape activity, such as settlements. Cropmarks found in the vicinity of some rondels indicate the presence of prehistoric dwellings such as timber pit-houses, although it is not currently possible to determine the chronological relationship between these features (Řídký Reference Řídký2011; Řídký et al. Reference Řídký, Květina, Limburský, Končelová, Burgert and Šumberová2018). As noted above, uniquely, we have been able to detect such associated features at the Drzemlikowice complex. There, alongside the rondel, we identified an ovaloid structure with a single ditch and a double palisade located to the north-west (Figure 5B & I; Figure 10, feature 11). Another, even smaller, structure with a diameter of approximately 45m is located nearby to south-west of the rondel (Figure 5C; Figure 10, feature 13).

Topographical analysis based on digital elevation models derived from airborne laser scanning, shows that rondels are usually located centrally within small- or medium-sized river valleys, occupying shallow slopes rather than prominent landforms. Any apparent linearity in the distribution of rondels is more likely to reflect adaptation to underlying landscape features than intentional alignment.

More generally, the distribution of these enclosures is not uniform. Some of them are isolated, located at distances of up to several dozen kilometres from each other (e.g. Bodzów, Drzemlikowice, Gniechowice, Proszkowice), while others form more distinct concentrations. An example of the latter is a pair of rondels and an undated third circular enclosure at Księginice Małe (Figure 7A–D). Both Neolithic rondels at Księginice Małe are typologically similar, in size and the numbers of ditches. Despite its ovaloid shape, the third enclosure (Figure 7E–F), with a diameter of approximately 100m, cannot currently be classified as a rondel, because no elements characteristic of rondels—gaps in ditches and palisades—are visible on the aerial photographs.

Another concentration or group comprises the three relatively large rondels from Sieroszów and Piotrowice Polskie, which are located on neighbouring hills, between 480 and 1200m apart (Figure 9). The clustering of two or more rondels within the same or adjacent geographical units, often exploiting distinctive terrain forms, is a common feature of rondels elsewhere (e.g. Bylany; Křivánek Reference Křivánek2020). These multi-rondel sites are argued to have played a role in symbolic competition between regional communities, who invested in these enclosures as part of translocal negotiation (Vondrovský et al. Reference Vondrovský, Kovačiková and Smejtek2022).

Discussion

The results presented here encourage discussion of the application and impact of new methods, as well as the implications of the newly discovered sites for understanding of the Early Neolithic period in Central Europe. Hardly any of the sites recorded during our programme of research were previously documented, for example, in the national Polish Archaeological Record (AZP). This probably reflects the lack of surface finds at these sites and hence their invisibility to fieldwalking surveys. In contrast, such surveys have identified clusters of settlements in the areas around the rondels and, while they cannot be assumed to be of the exact same date, the majority of the rondels are highly likely to be associated with these previously documented SBK communities.

As some of the enclosures are visible in multiple aerial images, taken at different times on different dates (particularly in Drzemlikowice), as well as in contemporaneous satellite imagery and orthophotos, our dataset allows us to assess the constantly changing appearance of cropmarks locally, regionally and temporally. Some rondels are more consistently visible within and between seasons than others, which are observed only sporadically and in such a way that does not allow for detailed interpretation and mapping. As a result, when interpreting the spatial distribution of remotely sensed sites, it is critical to ascertain the quantity and quality of the data available (Table 1). During our project, for example, we were able to acquire aerial imagery which captured substantially more detail than that available in freely accessible satellite imagery. Hence, while the assessment of such satellite imagery enables the identification of areas within which features might be anticipated, the ability to schedule aerial prospection to maximise the probability of detecting cropmarks greatly improves the chances of successfully identifying enclosure sites.

The combined application of aerial prospection and geophysical techniques to collect new data, especially on a landscape scale, has been advocated as a means of stimulating new insights into past societies (e.g. Campana & Piro Reference Campana and Piro2008). The integration of remote sensing methods presents an effective way to overcome the limitations of each technique, and can be used to correct misconceptions arising from a reliance upon the results of individual ground-based studies (Furmanek & Wroniecki Reference Furmanek, Wroniecki, Dębiec and Saile2020).

Nevertheless, remote-sensing techniques have their own limitations. Cropmarks and soilmarks are the result of intersecting formation processes and factors shaping their visibility (e.g. weather, crop types). As a result, the successful identification of sites is still often serendipitous. With this in mind, it is important to remember that remote-sensing surveys do not always provide a comprehensive record of archaeological features, but rather reflect areas of archaeological interest (e.g. Figure 2D), as well as favourable conditions for the appearance of cropmarks (see Cowley Reference Cowley, Forte and Campana2016). Hence, the distribution of rondels presented here is only provisional and will undoubtedly change in the future as new prospection programmes are initiated.

Technological changes (e.g. increasing the spatial and/or spectral resolution of vertical aerial photographs and satellite images) and increasingly access to open spatial datasets (e.g. in Poland, an orthophotomap is prepared every 2–3 years covering the whole country) present a wide range of both possibilities and challenges for archaeologists. The efficacy of remote sensing is, arguably, impacted by issues such as a lack of objectivity in the identification of archaeological features of interest, though new technologies will help to ensure more systematic extraction of sites and features (e.g. Casana Reference Casana2014; Verhoeven Reference Verhoeven2017). A fundamental challenge is the enormous quantity of data now available (e.g. satellite imagery, orthophotos), which demands bespoke and increasingly automated procedures. For example, deep-learning neural networks are increasingly used in numerous scientific domains, especially for image processing and feature extraction. Recently, the potential role of artificial intelligence in the analysis of imagery has come to the fore (Davis Reference Davis2019; Trier et al. Reference Trier, Cowley and Waldeland2019; Bonhage et al. Reference Bonhage, Eltaher, Raab, Breuß, Raab and Schneider2021). The distinctive circular forms of Neolithic rondels are especially well suited to such automated procedures. The value of these approaches have already been demonstrated (Wallner et al. Reference Wallner, Doneus, Kowatschek, Hinterleitner, Köstelbauer and Neubauer2022), particularly in the context of geophysical and airborne laser scanning datasets. Some archaeologists, however, suggest that a primary focus on discovery and the expansion of data resources solely through inductive reasoning may stifle the new thinking (Rączkowski Reference Rączkowski2020).

The discovery of new multiple new rondels in south-west Poland challenges current understanding of early farming communities north of the Carpathian and Sudeten Mountains. As LBK farming groups expanded across Central Europe in the sixth millennium BC, areas in south-west Poland became an integral part of the territory of the first European farmers, maintaining close connections with groups living along the Danube. Evidence for contact between these dispersed communities can be seen in the extensive networks for the exchange of flint and other stone raw materials, finished stone artefacts and ceramics (e.g. Mateiciucová Reference Mateiciucová2013). Strong similarities across this wide geographical area of the individual elements that constituted daily routines of settlement, construction, farming and ritual activities, may suggest the existence of a specific LBK ‘lifestyle’. With the gradual diversification of material culture from the early fifth millennium BC, most visible in ceramics, it is possible that these connections and shared ideas loosened or were realised in different ways. What united these increasingly different groups was probably ideology, and one manifestation of these shared ideas was the supra-cultural phenomenon of rondels.

With the arrival of the first farmers in Lower Silesia, the process of, often intensive, landscape transformations began (e.g. Furmanek et al. Reference Furmanek, Dreczko, Mozgała-Swacha, Kopec and Furmanek2019). Remote sensing can be used to document the diverse and often complex use of the land in the regions where rondels are identified. The precise chronologies of landscape use, however, cannot be clearly defined by most methods of prospection. As evidenced by the presence of characteristic early LBK architectural forms, such as long houses, the construction of some rondels was preceded by the existence of earlier domestic structures (e.g. Bodzów, Drzemlikowice) or older stages of SBK (for examples in other regions see Řídký et al. Reference Řídký, Květina, Limburský, Končelová, Burgert and Šumberová2018). This is a particularly frequent phenomenon in the area occupied by SBK communities, where continuity between the LBK and the SBK is well documented. The construction of these monumental enclosures in places of pre-existing settlement is unlikely to have been accidental and probably reflected social and ideological considerations and social memory (e.g. Řidký 2011). The number of rondel sites where contemporary surrounding features and structures have been detected is currently small and these are difficult to interpret without stratigraphic excavations and an advanced programme of absolute dating. Spatial proximity, and even the typological convergence of finds, does not necessarily imply contemporaneous activity.

Our research has proven that the fundamental explanation for this quagmire is the state of research, not past socio-cultural, economic or ideological influences. Observing a surge in information on rondels and other enclosures in Silesia does not reflect the region's uniqueness. Sites like this are likely to be more prevalent than previously realised. This is exemplified by further discoveries of rondel features even further towards the north, for example. in Wenecja in north-east Wielkopolska region and Nowe Objezierze in Western Pomerania (Czerniak et al. Reference Czerniak, Matuszewska, Dziewanowski, Pospieszny, Jakubczak, Szubski, Gebaer, Sørensen, Teather and Valera2020). This situation suggests the need to revise many views on the functioning of prehistoric communities as well as to advocate for the systematic use of ‘new and modern’ methods in an integrated manner.

Conclusions

We have used an integrated programme of non-invasive archaeological prospection methods to evaluate the distribution of Early Neolithic rondels in Lower Silesia. We hypothesised that the very limited numbers of known enclosure sites in this region was a function of a reliance on fieldwalking survey and that the collection and analysis of aerial and satellite imagery and geophysical survey would significantly increase the number of rondels detected. The results clearly show the effectiveness of using multiple non-invasive techniques to identify sites, such as rondels, which rarely produce surface finds. This approach and the new data it has generated significantly extend our understanding of the archaeological record of this region and, in turn, question the validity of existing interpretative narratives of the Early Neolithic period. Prior to this study, a reliance on fieldwalking data created the impression that rondels were few or entirely absent in Lower Silesia; this belief too easily conformed with traditional cultural-historical interpretations of this area as secondary and peripheral to the Neolithic cultural ‘centre’ of the Danube. It is now clear that rondels were widely present north of the Carpathian and Sudeten Mountains and that these structures were identical to those found further south in terms of size, morphology and spatial arrangement. These findings clearly refute the idea that communities located more distant from the Danube were culturally peripheral and only exhibited a subset of the characteristics of the Neolithic Danubian ‘core’. The eight rondels we have presented here are likely only the first of many to be discovered in the coming years as more work is undertaken in Lower Silesia. Even so, it is already clear that the farming communities of this region were an integral part of the Early Neolithic Central European world.

The introduction of new technologies and methods can push the discipline of archaeology forwards, opening new avenues of interdisciplinary research and encouraging both practical and theoretical advances. We therefore conceive of our work as part of what Kristian Kristiansen (Reference Kristiansen2014) has defined as archaeology's ‘third scientific revolution’, a stage when, in addition to the emergence and dissemination of new technologies, there has also been a reorientation of the theoretical foundations of the discipline. A consequence of this revolution is the blurring of the boundaries between previous approaches, such as processualism and post-processualism, modernism and postmodernism, or rationalism and romanticism, and the formation of a new paradigm.

Acknowledgements

Information about the features in Sieroszów A and B and Piotrowice Polskie was reported to the Lower Silesian Regional Heritage Office in Wałbrzych by Mariusz Dawid.

Funding statement

This research was funded by the Polish National Science Centre OPUS 19 project (UMO-2020/37/B/HS3/00540) and the Polish National Science Centre SONATA-BIS 3 project (DEC-2013/10/E/HS3/0014).