Introduction

The last two decades have fundamentally changed our understanding of cat domestication, primarily due to advances in palaeogenetic methods. Analyses of archaeological and modern felids have revealed the Near Eastern wildcat (Felis silvestris lybica) to be the common ancestor of all domestic cats (Driscoll et al. Reference Driscoll2007; Ottoni et al. Reference Ottoni2017). The primary domestication area was the Fertile Crescent, where wildcats were tamed around 10 000 years ago (Clutton-Brock Reference Clutton-Brock1999; Vigne et al. Reference Vigne2004; Faure & Kitchener Reference Faure and Kitchener2009; Ottoni et al. Reference Ottoni2017; Vigne Reference Vigne, Peters, McGlynn and Goebel2019). Subsequent evidence for cat domestication originates from Egypt around 3500 years ago and, for centuries, this served as the main hub for the worldwide spread of tamed/domesticated cats (Ottoni et al. Reference Ottoni2017). Our understanding of later dispersal in the Mediterranean is limited (Faure & Kitchener Reference Faure and Kitchener2009; Ottoni et al. Reference Ottoni2017), however, and barely anything is known about migrations beyond this region. Recent data indicate a significant overlap in the appearance of house mice (Mus musculus) and cats in Late Neolithic Eastern Europe (Cucchi et al. Reference Cucchi2020; Krajcarz et al. Reference Krajcarz2020), and suggest that the house mouse was an important factor for the dispersal of cats within Europe. Shipping and maritime trade are considered the most important factors for the spread of cats (Faure & Kitchener Reference Faure and Kitchener2009), but their remains are relatively rare in the archaeological record before the Late Middle Ages (von den Driesch Reference von den Driesch, Schmidt and Horzinek1992). In Europe, the increased popularity of cats is discernible in the zooarchaeological record as late as the second half of the thirteenth century (Faure & Kitchener Reference Faure and Kitchener2009).

The Five Thousand Years of History of Domestic Cat in Central Europe project

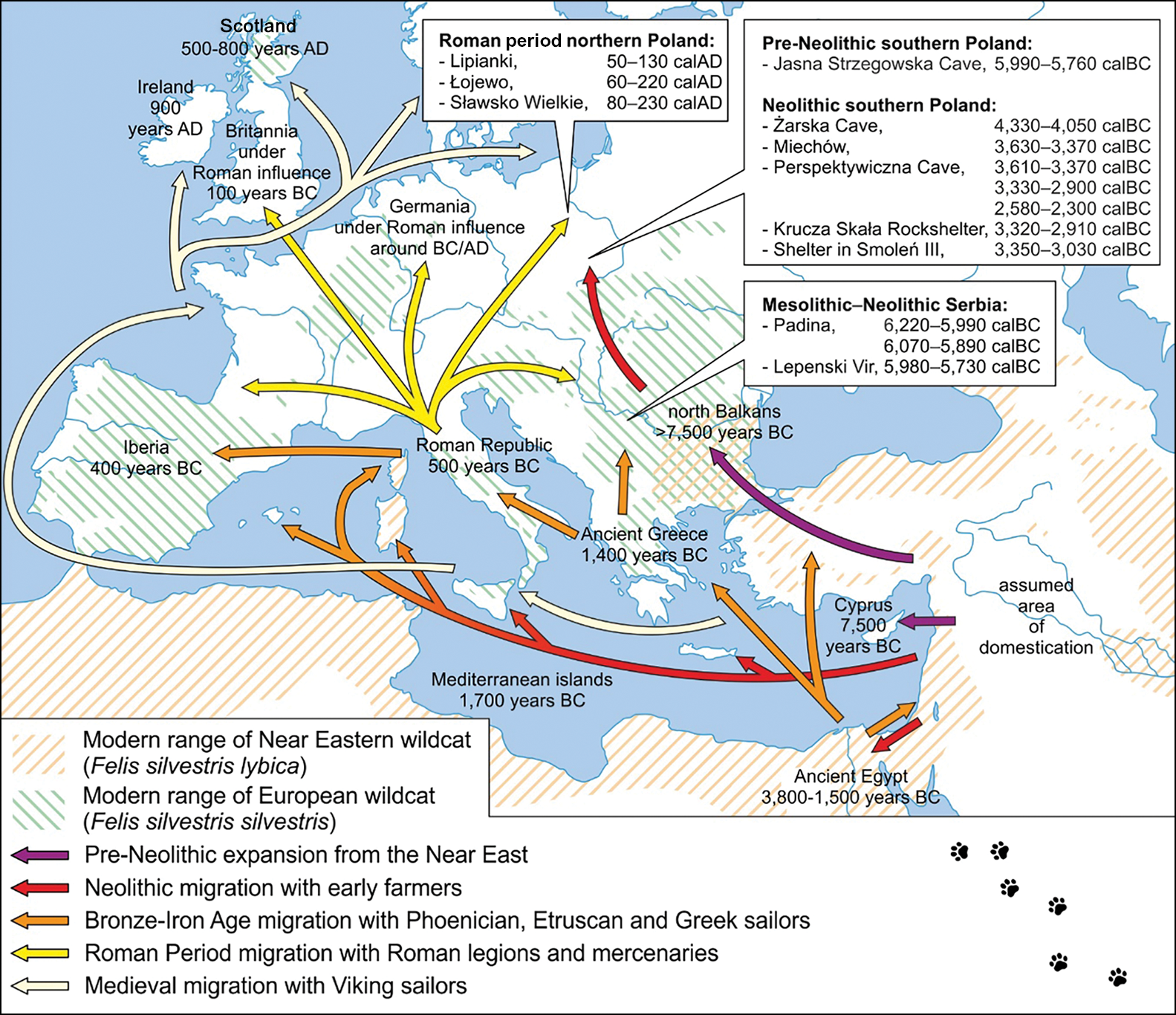

In 2016, we confirmed the appearance of domestic cats in Poland during the Roman period (Krajcarz et al. Reference Krajcarz2016) using a combination of zooarchaeology, genetics and absolute dating, pushing back their arrival by a millennium. We later demonstrated that cats bearing mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplotypes of the Near Eastern wildcat were already present in Central Europe in the Early Neolithic (Baca et al. Reference Baca2018), indicating that their dispersal into Central Europe was more complex than previously thought (Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1. Simplified routes for the early expansion of Felis silvestris lybica across Europe (based on our direct dating of the earliest Felis bones from Poland and Serbia in combination with data from Vigne et al. Reference Vigne2004; Driscoll et al. Reference Driscoll2007; Faure & Kitchener Reference Faure and Kitchener2009; Krajcarz et al. Reference Krajcarz2016, Reference Krajcarz2020; Ottoni et al. Reference Ottoni2017; Baca et al. Reference Baca2018). Age ranges are radiocarbon ages in years BC/AD produced using OxCal v.4.4 (at 95.4% probability), calibrated using the IntCal20 calibration curve (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2020) (figure by M.T. Krajcarz, using source data from The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (https://www.iucnredlist.org/)).

Figure 2. Selected mandibles of Near Eastern wildcats/domestic cats (a–f) and European wildcats (g–i) (species attribution based on mtDNA): a) Poland, Miechów site 3 (Neolithic); b–c) Poland, Łojewo site 4 and Sławsko Wielkie site 16 (Roman period); d–e) Serbia, Caričin Grad site (Early Byzantine period); f) Poland, Miechów site 3 (Middle Ages); g) Poland, Perspektywiczna Cave (Neolithic); h) Poland, shelter in Smoleń III (pre-Roman period); i) Poland, Perspektywiczna Cave (Middle Ages) (photographs by M. Krajcarz).

We set up the current project to investigate holistically the origins and dispersal of the domestic cat in Central Europe. It aims to expand our knowledge of the prehistory and early history of cats—that is, between their domestication in the Near East, earliest appearance in Central Europe, the later establishment of housecat populations during the Roman period, and the rapid increase of domestic cat populations in the late medieval period. The project also aims to identify phenotypic features related to domestication, such as: physical appearance, including body size and coat colour; behaviour, for example, reduced aggression; and possible physiological adaptations to digest anthropogenic food.

Our analyses combine palaeogenetics, including mitochondrial and nuclear DNA analysis, with zooarchaeology and direct radiocarbon dating. The goal is to elucidate high-resolution temporal changes in the genetic structure of past populations. Placing this information in a temporal and spatial framework will allow for the investigation of migration events and routes, as well as introgression events between the native European wildcat and domestic cat. A supra-regional database, which gathers mtDNA, nuclear DNA, morphometric, stratigraphic and radiocarbon data, is one of the planned outputs.

Preliminary results

The material collected thus far comprises more than 200 specimens from 102 sites (Figure 3) dating between the Late Pleistocene and modern period. Preliminary mtDNA results indicate that cats with the Near Eastern wildcat's A1 haplotype were present in Central Europe prior to the Neolithic. It was previously assumed that this haplotype is characteristic of non-domesticated Near Eastern wildcats, and its first appearance in Europe was detected in Romania c. 7700 BC (Ottoni et al. Reference Ottoni2017). Our data suggest that the range of the Near Eastern wildcat, or its hybrid zone with the European wildcat, could be much wider. We expect that ongoing nuclear DNA analyses will determine whether the observed range of the A1 haplotype is the result of natural gene flow between European and Near Eastern wildcats or an expansion of population.

Figure 3. Locations of archaeological and palaeontological sites from which cat remains have been collected for the project (figure by M.T. Krajcarz, using the base map generated in StepMap (https://www.stepmap.com/)).

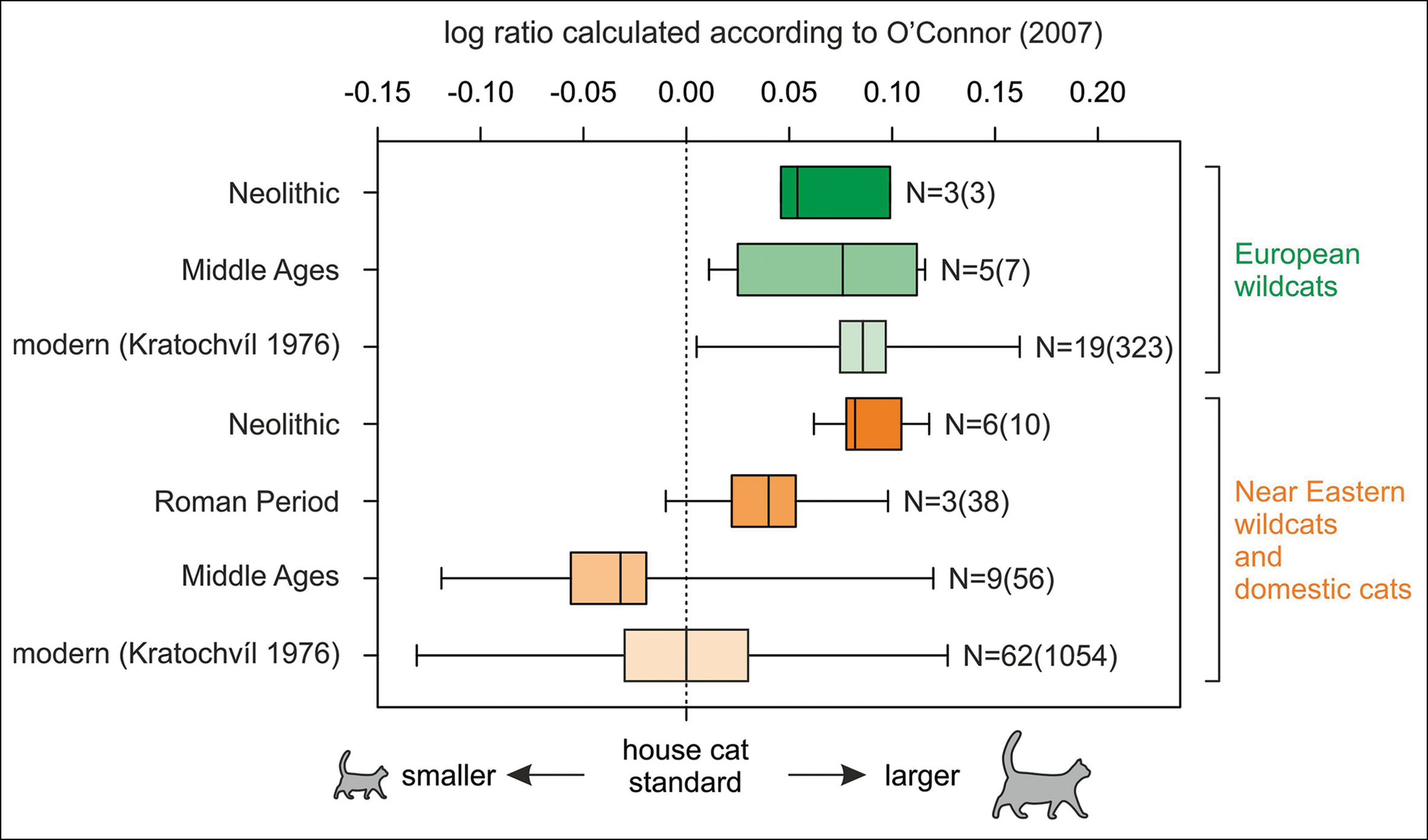

Our preliminary morphometric results, focused on Poland, reveal a decreasing trend in cat body size from the Neolithic to the medieval period (Figure 4). Neolithic cats were large individuals and equal in size to European wildcats, whose size remained stable over time. Bitz-Thorsen and Gotfredsen (Reference Bitz-Thorsen and Gotfredsen2018) found a similar trend within Bronze Age/Iron Age to medieval cats from Denmark. As we are still collecting data from the southern study area (the Carpathians and Balkans), which is situated closer to the Near Eastern wildcat's native range, more complex trends may eventually be recorded.

Figure 4. Changes in cat bone size over time. The log-ratio values show relative size against the standard of modern domestic cats (Kratochvíl Reference Kratochvíl1976; O'Connor Reference O'Connor2007). This allows comparison of measurements. Only long bones (humerus, ulna, radius, femur and tibia) from radiocarbon dated and mtDNA-identified specimens from Poland are used. N equates to the number of individuals, while the number in parentheses represents the number of measurements taken from them. Boxes display the standard deviation, while the line inside each box represents the mean and the whiskers represent the total range (figure by M. Krajcarz and M.T. Krajcarz, the boxplot generated using Past 4, version 4.05 (https://www.nhm.uio.no/english/research/resources/past/, Hammer et al. Reference Hammer2001)).

Funding statement

The Five Thousand Years of History of Domestic Cat in Central Europe: Interdisciplinary Study of Paleogenetics and Archaeozoology project is funded by the National Science Centre, Poland (grant no. 2019/35/B/HS3/02923).