The estimated number of Indigenous Peoples is approximately 370 million. The presence of Indigenous Peoples has been reported in over ninety countries and they represent about 5 % of the total world population( Reference Schrader-King 1 ). The most cited working definition of Indigenous Peoples is( 2 ):

‘Indigenous communities, peoples and nations are those which, having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing on those territories, or parts of them. They form at present non-dominant sectors of society and are determined to preserve, develop and transmit to future generations their ancestral territories, and their ethnic identity, as the basis of their continued existence as peoples, in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions and legal system.’

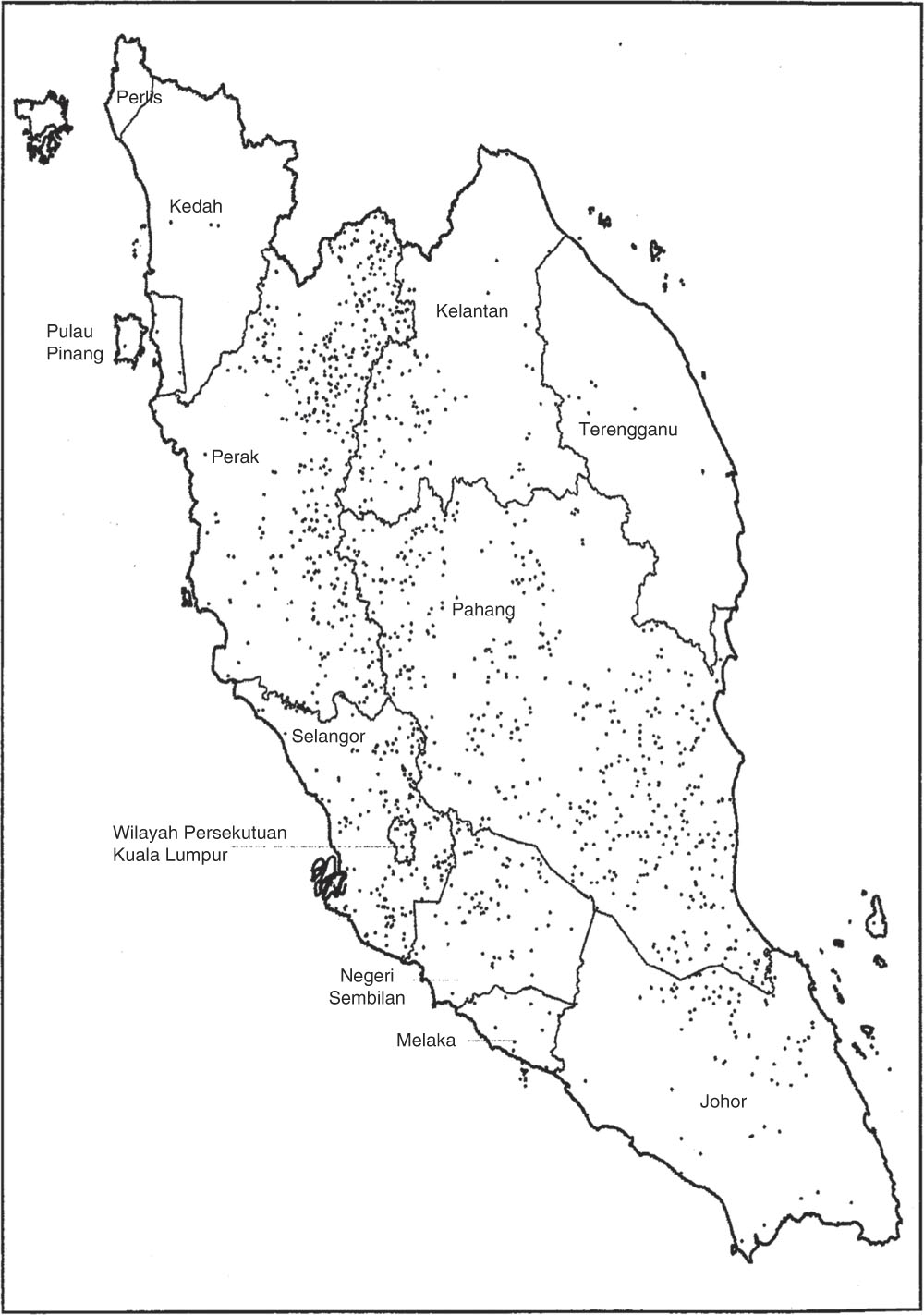

Indigenous Peoples in Malaysia are known as ‘Orang Asli’ (OA), which is defined as ‘First People’ in the Malay language( Reference Masron, Masami and Norhasimah 3 ). Data obtained directly from the Department of Orang Asli Development (JAKOA) showed that the total population of OA in Malaysia reached 178 197 in 2013. The OA population can be found throughout Peninsular Malaysia (as shown in Fig. 1 ( 4 )). The Indigenous population in Malaysia is divided into three main ethnic groups: Senoi, Proto-Malay and Negrito. Each ethnic group is then further divided into six more sub-ethnic groups, totalling eighteen sub-ethnic groups (Table 1).

Fig. 1 Distribution of the Orang Asli in Peninsular Malaysia in 2000; each dot represents 100 persons( 4 )

Table 1 Sub-ethnic groups of the Orang Asli in Malaysia( 4 )

Despite the fact that the population of Indigenous Peoples appears to be small, the population represents almost 10 % of the world’s poor in global terms( Reference Hall and Patrinos 5 ). Because of this fact, the food security status among Indigenous Peoples worldwide has been identified as one of the nutritional issues that causes the greatest concern. In Canada, data derived from various sources showed that the recorded prevalence rate of food insecurity was 70·2 % in Nunavut Inuit households, 43·0 % in Inuvialuit Inuit households and 44·2 % in Nunatsiavut Inuit households( 6 ). In addition, in Australia, about 9·0 % of the non-remote and 10·0 % of the remote Indigenous Peoples experienced instances where they had run out of food and had been unable to afford to buy food between the years 2012 and 2013. In a similar vein, another 13·0 % of the non-remote and 23·0 % of the remote Indigenous Peoples also ran out of food, however, did not suffer starvation during this same period( 7 ). In Malaysia, the prevalence rate of food insecurity among the OA in Selangor State exceeded 80·0 %( Reference Zalilah and Tham 8 , Reference Nurfahilin and Norhasmah 9 ). From previous reports and studies, it has been determined that the OA are a marginalised group with high poverty rate and low access to water, electricity, health-care services and children’s education( 10 ). The diet of the OA was reported to lack variety( Reference Haemamalar, Zalilah and Neng Azhanie 11 ). Because of these factors, development programmes for the OA are actively being continued under the eleventh Malaysia Plan 2016–2020( 12 ).

Coping strategies are defined by Maxwell as ‘fall back mechanisms to deal with the short-term insufficiency of food’( Reference Maxwell 13 ). There are three main purposes defined as reasons for practising coping strategies and these include increasing food production, increasing the ability to boost household income through new activities and seeking aid from relevant authorities( Reference Duhaime and Godmaire 14 ). The present paper has used in-depth interview techniques to garner more knowledge with regard to food insecurity issues among the OA. The study has explored the most common coping strategies practised by the OA in Peninsular Malaysia which arise when these households and individuals do not have enough food at home. Furthermore, focus group discussions (FGD) have been conducted to determine the level of severity for food insecurity that will trigger each specific coping strategy. The identification of each type of coping strategy and the associated level of severity is important because this information might thus potentially be used as an indicator that can assist the prediction of the occurrence of household food insecurity among the OA in the future.

Materials and methods

Study location

The study locations were selected through purposive sampling based on the name lists of food basket recipients (food baskets are a food aid programme from JAKOA which is targeted at the hardcore poor OA households in Malaysia)( 15 ). The coverage of the food aid programme encompassed all the OA registered under JAKOA. Based on the information from the name lists, the administrative regions of JAKOA were divided into three parts: Senoi-dominant, Proto-Malay-dominant and Negrito-dominant administrative regions. One administrative region was chosen from each of the aforementioned clusters. Then one district was selected from each of the chosen administrative regions. The eligible villages had to be reachable by a private car so that the selected villages were seen to share similar types of living environments. These villages had to be located in peri-urban areas and connected by proper roads to nearby towns. They also had to be surrounded by forests. A total of nine villages (three for each ethnic group) were selected from Gua Musang district, Kelantan State (Senoi dominant); Rompin district, Pahang State (Proto-Malay dominant); and Gerik district, Perak State (Negrito dominant). In each village, all eligible villagers were invited to participate in the study. Permission for conducting data collection in the OA villages was obtained from JAKOA. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects (JKEUPM) of Universiti Putra Malaysia (reference number FPSK(EXP15)P004).

Participants

The participants in the study consisted of sixty-one OA women from the three different ethnic groups outlined in the preceding subsection. The inclusion criteria were determined as being a mother who was of childbearing age (defined as aged between 20 and 49 years) who also had at least one child and was additionally from hardcore poor households (this factor was identified from the name lists of food basket recipients from JAKOA)( 16 ). Poverty in Malaysia is assessed by the Poverty Line Income in which a household has a monthly income that is less than Malaysian Ringgit (MYR) 520( 17 ). Hardcore poor families were a priority because they were viewed as being more vulnerable to household food insecurity( Reference Coleman-Jensen, Gregory and Rabbitt 18 ). The sample size for the study was determined using the saturation concept. The saturation of data occurs when it is noted that no more new information has emerged during the progression of the interview process( Reference Morse 19 ). Verbal and written informed consent was obtained from participants.

Measures

In-depth interviews

An in-depth interview approach was used to gather information from the participants. The use of in-depth interviews was selected as the method, instead of the planned FGD (as recommended by Maxwell and Caldwell)( Reference Maxwell and Caldwell 20 ). It was felt that in-depth interviews would work better and derive more information due to the reluctance of the OA to express themselves while in the presence of others and it was considered that this would be particularly true where matters of personal hardship were concerned. The interview sessions were conducted in the Malay language utilising local OA as translators because these translators were linguistically capable in both Malay and the native OA language. The interview sessions were audio-recorded. Two interview sessions for each participant were planned and then conducted. It was reasoned that by conducting more than one interview session a rapport could be established with the participants and this would also enable the participants to overcome any fear they had regarding the interview process. The two tools that were used for the interviews consisted of a sociodemographic questionnaire combined with the protocol set out for the interviewers.

During the first interview, the prepared questions covered the interviewee’s perceptions towards food, their food-seeking behaviours and the nutritional knowledge among the OA (a discussion of this nutritional knowledge is, however, beyond the scope of the present paper). The focus herein is on the findings that were derived from the second interviews, which were designed to identify the common coping strategies during a food shortage. The questions that were asked were:

1. What do you do when your household does not have enough food? (This was an assessment of behaviour following such an occurrence.)

2. Can you briefly explain how you perform the behaviour that you mentioned in question 1? (This was an explanation of the process that would be followed by the participant in the case of having a food shortage.)

Focus group discussions

Three FGD were conducted to determine the level of severity of the coping strategies that were identified from the in-depth interviews. The severity of a coping strategy was defined as the degree of household food insecurity arising when a coping strategy was practised and was based on the perception of the participants. The procedures to determine severity levels should have been conducted during the in-depth interviews, but it was found that the participants were not able to understand the questions directed to them due to having a poor level of education or no education at all. As a result, the FGD were added to the process in addition to the in-depth interviews.

The FGD were conducted in three OA villages in the Hulu Langat district, Selangor State, Malaysia. The same inclusion criteria as for the interviews were applied to select suitable participants, so that the living environments of the FGD participants retained a similarity to those of the participants in the in-depth interviews. Since the majority of the OA in Selangor are Proto-Malay, the JAKOA officer recommended three Proto-Malay villages that had poorer living conditions compared with other villages but that also had a higher literacy level. Six to seven participants were recruited for each of the three FGD, making a total of nineteen participants. Six to eight participants are deemed to be the preferred group size for FGD( Reference Krueger 21 ). The questions answered by the participants were:

1. What is the degree of household food insecurity when you practise this coping strategy?

2. Can you explain why you think so?

The degree of food insecurity was explained to the participants at the beginning of the discussion. ‘Less severe’ was defined as ‘feeling worried despite the food is still available’. In this case, little effort would be needed to increase food availability. ‘Severe’ was defined as a condition in which quantity and quality of food would begin to be compromised. In this case, there would be an urgent need to increase the household food availability. ‘Very severe’ was explained as being a food shortage in the household, where there was limited physical and economic access to food.

Quality control

A method known as triangulation was used to establish the trustworthiness, rigour and quality of the information obtained (that information being the type of coping strategies)( Reference Golafshani 22 ). There are five main types of triangulation: data triangulation, investigator triangulation, theory triangulation, methodologies triangulation and environmental triangulation( Reference Guion, Diehl and McDonald 23 ). The present study used only two types of triangulation, namely environmental triangulation and data triangulation. Environmental triangulation was conducted by involving three different locations: Gua Musang district (Kelantan State), Rompin district (Pahang State) and Gerik district (Perak State). Data triangulation was also conducted because the study involved the three main groups of OA: Senoi, Proto-Malay and Negrito. In this case, the environmental triangulation carried out was similar to the data triangulation because each ethnic group resided at their specific location without mixing with other ethnic groups. Information about coping strategies collected from each ethnic group at each location was then compared. Coping strategies that had been practised by all three ethnic groups were considered to have the highest trustworthiness.

Analysis

The data analysis for the demographic and socio-economic characteristics was performed using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics version 22. The numeric data were presented in medians and ranges, while the categorical data were reported in count (number) and proportion (percentage). The data analysis for the qualitative research was conducted by applying thematic analysis. The technical guides regarding thematic analysis developed by Braun and Clarke were followed( Reference Braun and Clarke 24 ). First, the verbal data from the interviews were transcribed verbatim. The transcribed notes were then read repeatedly in order to become familiar with the breadth of the data. The process of searching for meanings and patterns of the important information was conducted simultaneously during the reading process. After that, the coding process was carried out manually using highlighters or coloured pens. Each code that was identified, together with the relevant data extracts, were then kept in separate computer files. The codes identified were sorted into potential themes and the relevant coded data extracts were collated within the identified themes. The extracts of data for each theme were reviewed according to their coherence.

At the group level, the severity of a coping strategy was determined based on the majority of voices, particularly if the group had failed to achieve a consensus regarding the severity. For example, one situation arose when 70 % of the group thought that coping strategy A should be categorised as ‘less severe’ while 30 % thought it should be categorised as ‘severe’. Accordingly, coping strategy A was categorised as ‘less severe’ based on the majority of voices. Three levels of severity based on the opinions of the participants were determined: less severe, severe and very severe. Less severe was given a score of 1, severe was given a score of 2 and very severe was scored as 3. To determine the final severity, a calculation was carried out based on the following formula: sum of the severity level for the three focus groups/number of groups. The decimal number derived from this formula for the severity of each coping strategy was rounded up to the nearest integer. The formula was created based on the method described in Maxwell and Caldwell( Reference Maxwell and Caldwell 20 ).

Results

Semi-structured in-depth interviews

Demographic and socio-economic characteristics

The in-depth interviews involved sixty-one OA women from three ethnic groups at three locations. Half of the participants were from big households with four or more children. The literacy level of the participants was low, as a high percentage of them were from uneducated and low-educated backgrounds. All households were categorised as hardcore poor during interview except for one household (poor). The median monthly food and beverage expenses accounted for 50·0 % (16·7–100·0 %) of the monthly household income. The related details are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the participants: women from Orang Asli villages in the states of Kelantan, Pahang, Perak and Selangor, Peninsular Malaysia (in-depth interviews conducted from June to December 2015; focus group discussions conducted in January 2016)

MYR, Malaysian Ringgit.

Data presented are numbers of women, unless indicated otherwise.

* $US 1=MYR 4·3031 (31 December 2015).

† A household was categorised as poor due to job opportunity weeks before the interview was conducted. Her name is on the name list of food basket recipients in 2014. Therefore, she is eligible to participate in the present study.

Coping strategies

The participants provided twenty-nine coping strategies. The coping strategies were divided into two themes: food consumption (to increase food availability) and financial management (to increase household income and to reduce expenses). As additional information, all coping strategies were found to have been practised by the three ethnic groups apart from the following five specific strategies: buying large amount of food (Senoi and Proto-Malay), sending children to a relative’s or friend’s house (Senoi and Negrito), stopping schooling for children (Proto-Malay), sending children to work (Proto-Malay) and selling their own poultry (Senoi and Negrito). The summary of the coping strategies and participants’ responses is shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Common coping strategies and their frequencies as obtained from in-depth interviews with women (n 61) from Orang Asli villages in the states of Kelantan, Pahang and Perak, Peninsular Malaysia, June–December 2015

MYR, Malaysian Ringgit.

Food consumption coping strategies

The food consumption coping strategies were divided into four sub-themes: (i) dietary change; (ii) diversification of food sources; (iii) decrease in the number of people; and (iv) rationing. The first sub-theme focused on dietary change which consisted of alterations in the eating pattern, such as consuming white rice together with salt or seasoning and shifting to an alternative food that might not be a favourite food. The second sub-theme was diversification of food sources, which included searching for food from the surroundings and borrowing food from friends, neighbours, family members or relatives. The third sub-theme was to decrease the number of people who needed to be fed. Examples of reducing the number of people would be ordering children to eat at the homes of neighbours or relatives and bringing adult members to eat at the houses of friends or relatives. The fourth sub-theme was rationing. Examples of the practices of rationing were skipping meals and reducing portion size.

Financial management coping strategies

The financial management coping strategies comprised three sub-themes: (i) increasing the household income; (ii) reducing the expenses involved for children of school age; and (iii) reducing the expenses for daily necessities. The first sub-theme was increasing the household income. In cases where housewives needed money, they had to find forest commodities (such as durians, petai, bamboo shoots, insects and lizards) or to obtain a contract job from nearby farms. Under certain circumstances, the participants had had to sell their poultry in order to improve their financial situation. The second sub-theme was reducing expenses for the schooling of children. For the households with children of school age, the participants had occasionally reduced the pocket money provided to these children. In some serious cases, they ceased to provide money for a short period of time to the school-age children. The third sub-theme was to reduce the expenses required for daily necessities. For those houses with an electric supply, most of the participants reported that they had delayed the payment of the electricity bill. Also, the participants reported that they had seldom bought clothes as they did not have extra money.

Focus group discussions

Demographic and socio-economic characteristics

A total of nineteen Proto-Malay women took part in the FGD. There were some similarities between these women and the participants of the in-depth interviews; a high percentage of them were from big households that had four or more children and their literacy level was low due to a lack of education or a low formal education. According to the monthly household income, all the participants were rated hardcore poor during data collection. The median monthly household expenses were higher than those of the participants of the in-depth interviews. The related information is shown in Table 2.

Level of severity of the coping strategies

Regarding the severity of the coping strategies, there were eight coping strategies labelled as ‘less severe’. Examples of the coping strategies grouped under this category were eating without side dishes and getting water from a nearby river or lake. A total of seventeen coping strategies were categorised as ‘severe’. Examples of these severe coping strategies were requesting or borrowing money from others and purchasing cheaper food items. Only four coping strategies were classified as ‘very severe’: staying hungry, drinking fluid during hunger, ceasing to provide pocket money and stopping schooling for children. A summary of the severity level of each coping strategy and the participants’ responses is shown in Table 4.

Table 4 Severity of coping strategies as obtained from focus group discussions with women (n 19) from three Orang Asli villages in the state of Selangor, Peninsular Malaysia, January 2016

Discussion

The current study provided evidence regarding the practice of food consumption and financial management coping strategies among the OA during household food insecurity. The coping strategies covered both traditional food searching practices and practising cash economy (modern economy). The opinions of the OA were gathered through FGD, dividing the coping strategies into three levels of severity based on the degree of household food insecurity experienced when they practised these coping strategies.

Generally, the socio-economic status among the OA in Malaysia( Reference Lim, Romano and Colin 25 , Reference Mohamad Hafis, Ramle and Asmawi 26 ) has been reported as unsatisfactory. Despite having very low income, the OA participants reported spending about half of their income on food, a proportion considered to be only ‘moderately high’ for an impoverished group (18·0 % among the general Malaysian population)( 27 ). It would seem very likely that traditional food sources garnered through hunting, gathering and fishing reduced their reliance on money to ensure continued food supply( Reference Kardooni, Fatimah and Siti Rohani 28 ). The difference in food expenses between the in-depth interviewees and the FGD participants was mainly due to the geographical location because the participants in the FGD resided in more urbanised areas (such areas would have a higher cost of living).

The practice of coping strategies was found to be relevant to the entitlement theory proposed by Sen( Reference Sen 29 ). Hunger was found not to be due to low food availability but because of the lack of means to acquire food in other ways, which is known as entitlement failure. In a normal condition, an OA would be able to obtain food through traditional activities and purchasing. During a food shortage, however, coping strategies were practised by an OA in order to retain entitlement to food using methods such as changes in dietary pattern, diversification of food sources, decrease in the number people needing to consume food, rationing strategies and financial management. Starvation is a consequence of circumstances where the OA is no longer able to obtain enough food to sustain life( Reference Sen 29 ).

A total of twenty-nine coping strategies were identified. The coping strategies were found to fit into the categorisation recommended by Maxwell and Caldwell( Reference Maxwell and Caldwell 20 ). Maxwell and Caldwell were used as a reference due to their wide experience of these issues, and the set of coping strategies they proposed was based on the collective and conclusive discoveries from several studies conducted in nine countries in Africa( Reference Maxwell and Caldwell 20 ). There was some controversy regarding several pairs of the coping strategies identified, which require clarification. For example, eating rice with soya sauce or salt and buying cheaper food were not seen as similar behaviours to that of consuming less preferred food as far as the OA were concerned. This opinion was different from that of the general Malaysian population who considered that eating plain rice and eating less preferred food were identical behaviours( Reference Norhasmah 30 ). For the OA, eating plain rice was a simple meal that was within their tolerance range (but it was a decrease in food quality). Buying cheaper food was aimed at maintaining the food quantity by compromising the food quality. Most of the energy-dense food (such as salted fish, flour, canned food) would be cheaper than the nutrient-dense food. This finding did not imply, however, that OA disliked the cheaper food. Consuming less preferred food reflected an inability to be satisfied with the food, especially where it was a food that had been consumed persistently and that the OA would become bored with eating (such as potato or wild vegetables). The general Malaysian population has rated eating less preferred food and using less expensive food as ‘severe’ and ‘less severe’, respectively( Reference Norhasmah 30 ), an outcome which is not that different from that in the present study.

Bringing children into forests was considered dangerous. The coping strategies indicated a level of desperation among mothers in this situation where no one else was available to take care of the children. It can be concluded that children would not be asked to help in solving a food shortage. Moreover, never buying clothes and seldom buying clothes showed different degrees of money-saving behaviour and, in either case, more money could be allocated to food. Despite receiving donations of clothing from others, the OA still showed their desire to have new clothes but their ability to purchase new clothes greatly depended on their financial ability.

Buying food in small quantities for a single-day use such as one or two eggs, a handful of anchovies and a can of sardines demonstrated that OA in this situation had reduced access to food due to their economic circumstances. Buying in bulk (packs of rice, cooking oil and flour) acted as a strategy that helped to buffer lowered physical access to food. Since the current study was the first to explore coping strategies among the OA, the scope was not limited to those strategies aimed at solving the problems only related to economic access to food. The scope also encompassed strategies aimed at overcoming the problems pertaining to the limited physical access (borrowing a motorcycle) and improper food utilisation (taking water from the nearby river).

The OA share a certain degree of similarity in respect of the coping strategies with the First Nations, Métis and Inuit in Canada, namely finding food from the surroundings, dietary changes and reliance on food aid. These strategies were quite common for the OA, but they did not seem to share the practice of food storage( Reference Skinner, Hanning and Desjardins 31 ). With regard to food assistance programmes, there are similar programmes in both countries: the food basket from JAKOA and the Ministry of Health, as well as the Community Feeding Programme are abundant in Malaysia; while for their counterparts in Canada, food aid programmes such as food banks and soup kitchens are available( Reference Tam, Findlay and Kohen 32 ). The wide use of freezers among the Indigenous Peoples in Canada, alongside the traditional preservation of food using techniques such as smoking and drying, enables game meat to be stored for future consumption( Reference Skinner, Hanning and Desjardins 31 ). However, among the Malaysian OA, the affordability of refrigerators is low (11·5 %). The OA in Malaysia also enjoy a tropical rainforest climate, and food is available throughout the year in the surrounding environment and nearby marketplaces. Hence, the practice of preserving food is not considered a necessity. The OA are allowed to travel freely to search for food for their own consumption without any restriction, even in the forest reserves.

Several similar studies have been conducted among the major ethnic groups in Malaysia. By comparison with the coping strategies found by Shariff and Khor (who studied poor households in Sarbak Bernam, Selangor State), the present study shared similar findings except in the case of the strategy of reducing the number of people. Sending children to eat at other people’s houses was considered a food sharing practice among OA( Reference Shariff and Khor 33 ). Despite the similarity in the purpose of the coping strategies, the behaviours within the same groups in the different studies were distinguishable from each other, especially in terms of the non-food coping strategies. For example, the practice of using savings and selling valuable items (jewellery or land) were irrelevant for OA. Persistent poverty had depleted all the resources available for the OA, and therefore the OA did not have any savings or valuable items. Regarding food-related coping strategies, the main difference between the findings of the studies was the strategy of reducing the intake of fruits and vegetables as, in the case of the OA, wild fruits and vegetables could be obtained. Also, when compared with the study of Nurfahilin and Norhasmah (which was conducted among OA women in Gombak, Selangor State), the most obvious similarity with the current study was the practice of the traditional food searching behaviour of the OA (catching fish from the river and depending on forest resources)( Reference Nurfahilin and Norhasmah 9 ).

The coping strategies were categorised into ‘less severe’, ‘severe’ and ‘very severe’, and this was the same for a study conducted by Maxwell( Reference Maxwell 13 ), where the coping strategies were also categorised into three degrees of severity weighting. Eating less preferred food and limiting portion size were considered as having equal severity but were felt to be less severe than borrowing food and money, maternal buffering and skipping meals, which were again considered to have lower severity compared with skipping meals( Reference Maxwell 13 ). Sulaiman et al. ( Reference Sulaiman, Shariff and Jalil 34 ) and Maxwell and Caldwell( Reference Maxwell and Caldwell 20 ) divided the severity weighting into four categories: ‘not severe’, ‘quite severe’, ‘severe’ and ‘very severe’. Differentiating the coping strategies into more levels of severity is an advantage when the coping strategies are used as weighted items in a questionnaire, as the classification by the respondents into different food security statuses can be determined more precisely. The establishment of the level of severity for each coping strategy has provided proof that food security is a managed process( 35 ). Food insecurity was found to affect the quantitative, qualitative, psychological and social dimensions at both the household and the individual levels( Reference Radimer, Olson and Greene 36 ).

There were several limitations in the design of the current research. The participants were mainly from villages that were easily accessible using a normal car. The voice of the OA in the remote areas was not obtained. The food insecurity conditions in remote areas might be more critical as the communities have to depend on food from the surroundings to survive as the food aid is limited. Only female participants were involved because women are more familiar with the dietary condition of the families( Reference Kardooni, Fatimah and Siti Rohani 28 ). However, it is recognised that involving male participants would have enriched the content of the information, especially regarding the socio-economic background of the households( Reference Kardooni, Fatimah and Siti Rohani 28 ).

The information obtained might be contaminated by false positive responses due to the influence of others involved in the process, especially the translators. During the interviews, the translators might provide unnecessary hints to the participants and lead them to provide false positive answers. Proper training should be provided to the translators before data collection. A high proportion of the participants were semi-literate or illiterate. The language barrier and cultural diversity could have led to misinterpretation of the questions and that might have affected the quality of the information gathered( Reference Bwambale, Moyer and Komakech 37 ). The hiring of translators could have reduced the undesired biases.

Lastly, different samples were used during the in-depth interviews (three ethnic groups) and the FGD (one ethnic group). There is a possibility that the FGD participants did not have a similar experience to the in-depth interviewees, as each individual would have had a unique approach to the coping strategies they practised. Besides that, due to this condition, the environmental triangulation was applicable only to examine the quality in the types of coping strategy identified (three locations) but not the quality of the severity identified (one location). In this case, the opinions of the FGD participants in rating the severity of specific coping strategies might have been different from those of the in-depth interviewees. The study provides direction for future studies in terms of sample selection. Selecting proactive participants with moderate education can prevent the involvement of two different groups of participants (inability to answer questions) and reduce the occurrence of biases (due to misinterpretation). Help from villages chiefs can be sought to identify the desired participants.

Conclusion

The interviews conducted among the OA provided information regarding the types of coping strategies practised during food insecurity. This information would enable local authorities or non-governmental organisations to more precisely target and plan interventions in order to better aid the OA communities needing assistance in the areas of food sources and financial management. With the available knowledge, the list of coping strategies together with their respective severity level can be used to develop a cultural-specific household food insecurity measuring instrument that is able to determine the level of severity of household food insecurity among the OA in Peninsular Malaysia. The proposed instrument is believed to possess several advantages compared with the existing instruments in terms of better cultural compatibility and overcoming the language barrier. With the development of this instrument, a systematic monitoring system is made possible.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank the officers from the Department of Orang Asli Development (JAKOA) and all participants for their cooperation and support for this research project. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: All the authors participated in formulating the research questions and designing the study. L.S.L. was responsible for collecting and analysing the data with guidance from S.N., W.Y.G. and M.T.M.N. L.S.L. drafted the manuscript. S.N., W.Y.G. and M.T.M.N. critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects, Universiti Putra Malaysia (reference number FPSK(EXP15)P004). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.