Raising a happy, confident, and resilient adolescent is not always easy (Putnick et al., Reference Putnick, Bornstein, Hendricks, Painter, Suwalsky and Collins2010; Twenge et al., Reference Twenge, Cooper, Joiner, Duffy and Binau2019), as evidenced by the many parenting self-help books on the market (e.g., Steinberg, Reference Steinberg2011). Parents experience that general parenting principles described in parenting books may not apply to their own unique adolescent children (e.g., Bülow et al., Reference Bülow, Neubauer, Soenens, Boele, Denissen and Keijsers2022; Mabbe et al., Reference Mabbe, Vansteenkiste, Brenning, De Pauw, Beyers and Soenens2019). Environmental sensitivity models explain why children (including adolescents) may be differently affected by the same parenting influences (Greven et al., Reference Greven, Lionetti, Booth, Aron, Fox, Schendan, Pluess, Bruining, Acevedo, Bijttebier and Homberg2019; Pluess, Reference Pluess2015). That is, some children perceive and process environmental influences more intensely than others, which could make some children more sensitive and responsive to parenting (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van Ijzendoorn2007; Belsky & Pluess, Reference Belsky and Pluess2009). However, different models describe different patterns, with responsivity to primarily: (1) adverse parenting (“for worse”; Monroe & Simons, Reference Monroe and Simons1991; Zuckerman, Reference Zuckerman1999); or (2) supportive parenting (“for better”; Pluess, Reference Pluess2017); or (3) to both (“for better and for worse”; Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van Ijzendoorn2007; Belsky & Pluess, Reference Belsky and Pluess2009). It has been suggested, but never tested, that these three sensitivity types co-exist (Pluess, Reference Pluess2015), rather than being mutually exclusive. In line with this theorizing, the current study tested whether adolescents responded differently to adverse and supportive parenting. Hence, this study aimed to increase the understanding of heterogeneity in parenting effects, and whether this heterogeneity can be explained by environmental sensitivity models. To achieve this, we took an innovative approach in which individual adolescents, rather than (sub)group averages, are the key unit of observation.

For better, for worse, or for both?

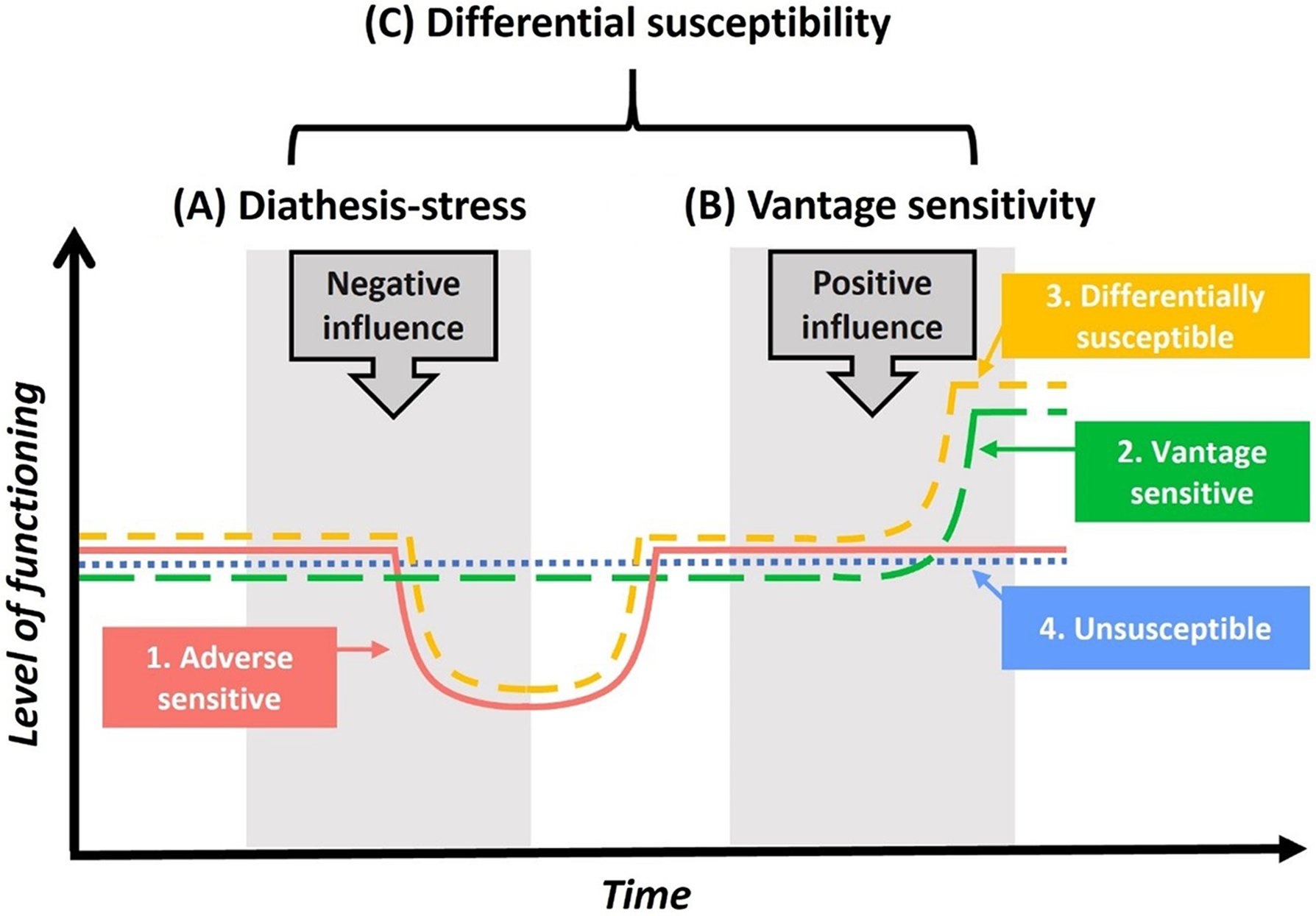

Environmental sensitivity models assume that humans vary in their ability to perceive, processes, and respond to environmental influences (Pluess, Reference Pluess2015; Tillmann et al., Reference Tillmann, Bertrams, El Matany and Lionetti2021). Currently, three different theories propose different ideas about the type of environmental influences more environmentally sensitive individuals respond more strongly to (see Figure 1). The classic (1) diathesis-stress (or dual-risk) model suggests that some individuals are primarily adverse sensitive and therefore show stronger responsivity to adverse environmental influences (“for worse”; Monroe & Simons, Reference Monroe and Simons1991; Zuckerman, Reference Zuckerman1999). Adverse sensitive children are for instance assumed to suffer more (e.g., internalizing problems) from psychologically controlling parenting (Nelemans et al., Reference Nelemans, Keijsers, Colpin, van Leeuwen, Bijttebier, Verschueren and Goossens2020; van der Kaap-Deeder et al., Reference van der Kaap-Deeder, Vansteenkiste, Soenens and Mabbe2017). In contrast, the (2) vantage sensitivity model emphasizes primarily reactions to positive environmental qualities, such as emotionally supportive parenting (e.g., Han & Grogan-Kaylor, Reference Han and Grogan-Kaylor2013; Lippold et al., Reference Lippold, Davis, McHale, Buxton and Almeida2016). This model thus specifies that some individuals benefit more strongly from positive, supportive environments (“for better”; Pluess, Reference Pluess2017; Pluess & Belsky, Reference Pluess and Belsky2013). Finally, there are (3) “for better and for worse” models, including the sensory processing sensitivity (Aron & Aron, Reference Aron and Aron1997), biological sensitivity to context (Boyce & Ellis, Reference Boyce and Ellis2005; Ellis & Boyce, Reference Ellis and Boyce2008), and differential susceptibility models (Belsky, Reference Belsky1997; Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van Ijzendoorn2007; Belsky & Pluess, Reference Belsky and Pluess2009). The latter set of theoretical models offer an alternative explanation and propose that sources of environmental sensitivity (e.g., temperamental and genetic variants) not only makes individuals more prone to suffer from adverse environments but also more likely to benefit from supportive environments. Although the three theories converge in their ideas to which type of environmental influences highly sensitive individuals respond more strongly, they all agree that there is another subgroup who is much less or not at all responsive to environmental influences (“for neither”).

Figure 1. The “coexisting responsivity patterns hypothesis” proposes that the three different environmental sensitivity models coexist. The models describe either a subgroup showing responsivity: (1) “for worse” (diathesis-stress, left panel); (2) “for better” (vantage sensitivity, right panel); or (3) “for better and for worse” (differential susceptibility, left & right panel). All models describe another subgroup showing; (4) no responsivity, thus “for neither”. Based on Figure 1 in “Individual Differences in Environmental Sensitivity,” by M. Pluess, Reference Pluess2015, Child Development Perspectives, 9, pp. 138–143.

After the formulation of “for better and for worse” models, empirical parenting research tried to establish which of the three theoretical models best describes the empirically observed responsivity patterns by person × environment interactions (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van Ijzendoorn2007, Reference Belsky, Pluess and Widaman2013; Jolicoeur-Martineau et al., Reference Jolicoeur-Martineau, Belsky, Szekely, Widaman, Pluess, Greenwood and Wazana2019; Roisman et al., Reference Roisman, Newman, Fraley, Haltigan, Groh and Haydon2012). That is, studies competitively evaluated whether the pattern of moderation effects were consistent with either the diathesis-stress, vantage sensitivity, or differential susceptibility models. Nonetheless, systematic reviews highlight inconsistent findings across studies. Evidence for all three theories have been presented, depending on the studied parenting practice, child outcome, sensitivity marker, age group, assessment method, and so forth (for reviews see, Rabinowitz & Drabick, Reference Rabinowitz and Drabick2017; Rioux et al., Reference Rioux, Castellanos-Ryan, Parent and Séguin2016; Slagt et al., Reference Slagt, Dubas, Deković and van Aken2016). Hence, to date, there seems to be inconclusive evidence for either one of the theoretical models, which raises the possibility that all models may co-exist and that differences in empirical findings are due to methodological factors (Pluess & Belsky, Reference Pluess and Belsky2012, Reference Pluess and Belsky2013).

Indeed, Pluess (Reference Pluess2015) hypothesized the coexistence of different sensitivity types. He theorized that individuals can become sensitive to either adverse or supportive influences or to both influences, because of the interaction between genetic disposition and experiences in early development. For example, children who carry genes for environmental sensitivity may become particularly sensitive to adverse influences when growing up in very stressful conditions, whereas others may become particularly sensitive to supportive influences when growing up in very supportive conditions. Children who carry sensitivity genes and grow up in a more neutral environment (which is neither very stressful or supportive), may remain sensitive to both adverse and supportive influences. Being more sensitive in perceiving and processing adverse and/or supportive influences can manifest in a heightened responsivity to those influences (Pluess, Reference Pluess2015).

Accordingly, different responsivity patterns – adverse sensitive, vantage sensitive, and differentially susceptible – may coexist and apply to different subgroups of individuals (Pluess, Reference Pluess2015; Pluess & Belsky, Reference Pluess and Belsky2012, Reference Pluess and Belsky2013). When applying to parenting, this “coexisting responsivity patterns hypothesis” implies that: (a) some children may primarily experience negative effects of adverse parenting; (b) others may primarily experience advantageous effects of supportive parenting; and (c) some others may experience both. And finally, (d) some experience neither such positive nor negative effects, as consistent with all three models (see Figure 1). To test this hypothesis, an approach is needed that allows to examine which responsivity pattern applies to each individual (Pluess & Belsky, Reference Pluess and Belsky2013). In the current study, we investigated this hypothesis in adolescence, by using intensive longitudinal data of families who bi-weekly reported on both adverse (i.e., psychological control) and supportive (i.e., warmth/support) parenting, and varying indicators of adolescents’ psychological functioning as outcomes (i.e., self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms).

Effect heterogeneity in within-family parenting effects

Parenting takes place within a family (i.e., within-family level), such that parents impact their own children (Belsky & Pluess, Reference Belsky and Pluess2009; Darling & Steinberg, Reference Darling and Steinberg1993; Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2010). Nonetheless, until recently few empirical studies have conceptualized parenting effects as a phenomenon at the within-familyFootnote 1 level (Boele et al., Reference Boele, Denissen, Moopen and Keijsers2020; Hamaker, Reference Hamaker, Mehl and Conner2012; Keijsers, Reference Keijsers2016). Instead, most of what is currently known of how parenting relates to adolescent functioning comes from research describing differences between families in their average levels of parenting and adolescent functioning (between-family level; e.g., McLeod et al., Reference McLeod, Weisz and Wood2007; Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2017). Studies examining differential parenting effects have followed the dominant approach and established how between-family parenting effects differ among subgroups of adolescents (e.g., Chavez Arana et al., Reference Chavez Arana, de Pauw, van IJzendoorn, de Maat, Kok and Prinzie2021; Olofsdotter et al., Reference Olofsdotter, Åslund, Furmark, Comasco and Nilsson2018; Tung et al., Reference Tung, Noroña, Morgan, Caplan, Lee and Baker2019). However, parenting is not set in stone and fluctuates and changes over time within the same family (Boele et al., Reference Boele, Nelemans, Denissen, Prinzie, Bülow and Keijsers2022; Darling & Steinberg, Reference Darling and Steinberg1993; Keijsers et al., Reference Keijsers, Boele and Bülow2022). Additionally, the effects that parents have upon their own adolescent may also be unique to each family (i.e., effect heterogeneity; Bolger et al., Reference Bolger, Zee, Rossignac-Milon and Hassin2019; Grusec, Reference Grusec, Kerr and Engels2008; Keijsers & Van Roekel, Reference Keijsers, Van Roekel, Hendry and Kloep2018). According to environmental sensitivity theories for example, some adolescents respond more strongly to parenting because they are more environmentally sensitive than others (Pluess, Reference Pluess2015). Thus, to understand how parenting effects unfold over time within different families, the current study employs a within-family design.

To be able to make inferences about parenting effects within families, a multilevel approach is needed that disentangles stable between-family differences and over-time within-family effects (Hamaker, Reference Hamaker, Mehl and Conner2012; Keijsers, Reference Keijsers2016). Doing so, several studies have now, for example, demonstrated that how parenting relates to adolescents’ functioning at the between-family level can sometimes be in opposite direction as the effects at the within-family level (e.g., Dietvorst et al., Reference Dietvorst, Hiemstra, Hillegers and Keijsers2018; Nelemans et al., Reference Nelemans, Keijsers, Colpin, van Leeuwen, Bijttebier, Verschueren and Goossens2020; Villalobos Solís et al., Reference Villalobos Solís, Smetana and Comer2015). In the current study we applied dynamic structural equation modelling (DSEM; Asparouhov et al., Reference Asparouhov, Hamaker and Muthén2018), which is a type of multilevel modelling that is especially suited for intensive longitudinal data. DSEM combines the strengths of multilevel modelling, SEM, and N = 1 time series. Hence, DSEM allowed us to estimate within-family parenting effects for each individual adolescent in the sample separately (for other examples, see Beyens et al., Reference Beyens, Pouwels, van Driel, Keijsers and Valkenburg2021; Bülow, Neubauer, et al., Reference Bülow, Neubauer, Soenens, Boele, Denissen and Keijsers2022).

The current study

The aim of this preregistered within-family studyFootnote 2 was to increase the understanding of heterogeneity in parenting effects, and whether this heterogeneity can be explained by environmental sensitivity models. Therefore, we tested per individual adolescent whether they suffered from adverse parenting (adverse sensitive), benefited from supportive parenting (vantage sensitive), experienced both (differentially susceptible), or neither of the two (unsusceptible). To do so, we intensively followed families for 26 bi-weekly measurement occasions, thus spanning a full year.

To follow guidelines of Belsky & Pluess (Reference Belsky and Pluess2009) and Pluess & Belsky (Reference Pluess and Belsky2013), we examined the responsiveness of individual adolescents to over-time changes in both adverse and supportive parenting. In line with prior studies (e.g., Slagt et al., Reference Slagt, Dubas, Deković and van Aken2016; Weyn et al., Reference Weyn, Van Leeuwen, Pluess, Lionetti, Greven, Goossens, Colpin, Van Den Noortgate, Verschueren, Bastin, Van Hoof, De Fruyt and Bijttebier2021) and recommendations (e.g., Belsky & Pluess, Reference Belsky and Pluess2009; Pluess & Belsky, Reference Pluess and Belsky2013), adverse parenting was measured as psychological control and supportive parenting as emotional support (rather than treating the absence of adversity as a supportive condition). Parental psychological control includes behaviors such as intrusiveness, criticism, and manipulation (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Xia, Olsen, McNeely and Bose2012; Soenens & Vansteenkiste, Reference Soenens and Vansteenkiste2010). Parental emotional support (hereafter called support) includes warmth, affection, companionship, and intimacy (Furman & Buhrmester, Reference Furman and Buhrmester1985; Soenens et al., Reference Soenens, Deci, Vansteenkiste, Wehmeyer, Little, Lopez, Shogren and Ryan2017). According to the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), parental psychological control actively thwarts children’s psychological functioning, whereas parental support actively promotes children’s psychological functioning (Soenens et al., Reference Soenens, Deci, Vansteenkiste, Wehmeyer, Little, Lopez, Shogren and Ryan2017). Accordingly, parental psychological control can be understood as a risk factor, with more psychological control hindering children’s psychological functioning, whereas a lack of psychological control is not necessarily fostering better functioning. Parental support can be understood as a promotive factor, with more support promoting better psychological functioning, whereas a lack of support is not necessarily hindering children’s functioning (Farrington et al., Reference Farrington, Ttofi and Piquero2016; Soenens et al., Reference Soenens, Deci, Vansteenkiste, Wehmeyer, Little, Lopez, Shogren and Ryan2017; Stouthamer-Loeber et al., Reference Stouthamer-Loeber, Loeber, Wei, Farrington and Wikström2002). Hence, we examined whether changes (in relation to an individual’s average) in parental psychological control and/or support predicted within-family changes in adolescents’ psychological functioning. In prior within-family studies, parental psychological control (Mabbe et al., Reference Mabbe, Vansteenkiste, Brenning, De Pauw, Beyers and Soenens2019; Nelemans et al., Reference Nelemans, Keijsers, Colpin, van Leeuwen, Bijttebier, Verschueren and Goossens2020; Van Lissa et al., Reference Van Lissa, Keizer, Van Lier, Meeus, Branje and Lissa2019) and parental support (for review see Boele et al., Reference Boele, Denissen, Moopen and Keijsers2020, Reference Boele, Nelemans, Denissen, Prinzie, Bülow and Keijsers2022) have not consistently predicted adolescent psychological functioning, perhaps because some adolescents are more affected than others as environmental sensitivity theories suggest.

Moreover, recently it has been gained attention that one’s environmental sensitivity might not generalize to different outcomes (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Zhang and Sayler2021). Additionally, in (developmental) psychology it has been stressed that that the same influence may lead to different outcomes depending on the child (i.e., the principle of multifinality; Cicchetti & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch1996) and that absence of dysfunction is not by itself an indicator of good functioning (Belsky & Pluess, Reference Belsky and Pluess2009; Keyes, Reference Keyes, Bauer and Hämmig2014; Ryff et al., Reference Ryff, Dienberg Love, Urry, Muller, Rosenkranz, Friedman, Davidson and Singer2006). Therefore, we examined three different indicators of adolescents’ psychological functioning, including one positive (i.e., self-esteem) and two negative indicators (i.e., depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms). In sum, the responsivity-to-parenting patterns were based on two parenting dimensions and three adolescent outcomes.

As a last step, to test whether adolescents with different responsivity patterns can also be detected using a theory-based sensitivity marker (Greven et al., Reference Greven, Lionetti, Booth, Aron, Fox, Schendan, Pluess, Bruining, Acevedo, Bijttebier and Homberg2019; Pluess, Reference Pluess2015; Pluess et al., Reference Pluess, Assary, Lionetti, Lester, Krapohl, Aron and Aron2018), we compared empirically derived subgroups on trait levels of environmental sensitivity. We used a self-report measure of the Highly Sensitive Child Scale to examine these individual differences in environmental sensitivity (HSC; Pluess et al., Reference Pluess, Assary, Lionetti, Lester, Krapohl, Aron and Aron2018; Weyn et al., Reference Weyn, Van Leeuwen, Pluess, Lionetti, Greven, Goossens, Colpin, Van Den Noortgate, Verschueren, Bastin, Van Hoof, De Fruyt and Bijttebier2021).

Hypotheses

First, we expected that, on average, increases in parental psychological control are followed by decreases in adolescents’ self-esteem (H1a) and by increases in adolescents’ depressive and anxiety symptoms (H1b), whereas increases in parental support are followed by increases in adolescents’ self-esteem (H1c) and decreases in adolescents’ depressive and anxiety symptoms (H1d). Second, based on the aforementioned environmental sensitivity models (for overview, see Greven et al., Reference Greven, Lionetti, Booth, Aron, Fox, Schendan, Pluess, Bruining, Acevedo, Bijttebier and Homberg2019 and Figure 1) as well as the first studies on parenting effect heterogeneity (Bülow, van Roekel, et al., Reference Bülow, van Roekel, Boele, Denissen and Keijsers2022; Janssen, Elzinga, et al., Reference Janssen, Elzinga, Verkuil, Hillegers and Keijsers2021), we expected differential parenting effects across families; Hence, we hypothesized between-family variance around these average within-family parenting effects (H2).

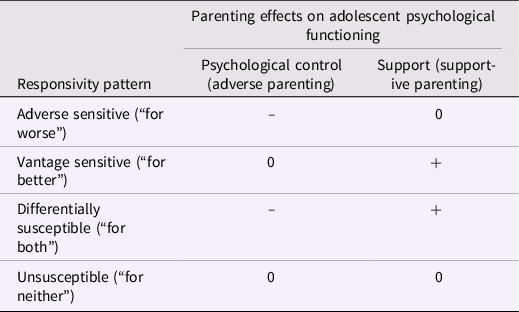

Third, our main hypothesis was the “coexisting responsivity patterns hypothesis”, in which we expected that three environmental sensitivity theoretical models coexist in the sample and apply to different subgroups of adolescents (H3) (Pluess & Belsky, Reference Pluess and Belsky2012, Reference Pluess and Belsky2013). To test this, we described how many adolescents in our sample demonstrated one of the following responsivity patterns: adverse sensitive (“for worse”), vantage sensitive (“for better”), differentially susceptible (“for better and for worse”) or unsusceptible (“for neither”). A description of the pattern of parenting effects for each responsivity pattern is described in Table 1. For example, an adolescent was considered adverse sensitive if parental psychological control, but not parental support, predicted decreased psychological functioning (i.e., lower self-esteem and/or more depressive symptoms and/or more anxiety symptoms). We preregistered that H3 is confirmed if we would find more than one responsivity pattern in our sample. We did not have a priori hypotheses regarding to how many adolescents in our sample would show these responsivity patterns.

Table 1. Hypothesized coexisting responsivity patterns

Note. Effect on adolescent psychological functioning pertains an effect on self-esteem and/or depressive symptoms and/or anxiety symptoms.

0 = null effect (–.05 > β < .05), + = positive effect (β ≥ .05), - = negative effect (β ≤ –.05).

Fourth, we hypothesized that trait levels of environmental sensitivity (i.e., sensory processing sensitivity; Aron et al., Reference Aron, Aron and Jagiellowicz2012) would be linked to the empirically derived responsivity patterns, because the trait environmental sensitivity captures the general ability to perceive, processes, and respond to environmental influences (Pluess, Reference Pluess2015; Tillmann et al., Reference Tillmann, Bertrams, El Matany and Lionetti2021). The HSC is suggested to be marker for a “for better and for worse” responsivity pattern (Pluess et al., Reference Pluess, Assary, Lionetti, Lester, Krapohl, Aron and Aron2018; Slagt et al., Reference Slagt, Dubas, Aken and Ellis2018). However, because it has not been tested how the HSC predicts within-family parenting effects, we tentatively formulated the following hypothesis (H4): Differentially susceptible adolescents (see H3) would be more environmentally sensitive than other adolescents, especially more than unsusceptible adolescents, but possibly also more than adverse sensitive and vantage sensitive adolescents.

Method

Participants

Adolescents (N = 259) participated in a longitudinal study called “One size does not fit all” (http://osf.io/e2jzk). Data, of which 256 adolescents (M age = 14.4, SD age = 1.59, age range = 12–17 years, 71.5% female) contributed data on our study constructs. Most of these adolescents (97%) and their parents (95%) were born in the Netherlands. Concerning adolescents’ educational level, 15% followed (pre-)vocational secondary education, 36% higher general secondary education, and 49% pre-university secondary education. Their primary caregivers were mostly their mothers (81%; with whom they spend most of their time), although for 19% their father was their primary caregiver. Most parents were married/living together (76%), some were divorced or separated (21%), and a few deceased (3%). Highest educational level of (one of) their parents were primary education (1%), secondary education (1%), vocational training (13%), university of applied sciences (38%), university (28%). We had insufficient information about parental education of 51 adolescents (20%). Many adolescents had siblings (92%), such as one (52%) or two siblings (34%), with a maximum of five (1%).

Adolescents could participate with at least one parent. In total, 188 parents (M age = 46.89, age range = 36–76, 90% Dutch) participated in this longitudinal study. These parents were the biological mothers (78%) or fathers (22%). Most of the participating parents finished post-secondary education: vocational training (35%), university of applied sciences (35%), or university (18%). Forty-six percent of the parents were religious (and in those cases mainly Christian, 88%).

Procedure

From September to November 2019, adolescents between 12 and 17 years old and their parents were recruited at a Dutch high school through parent-evenings, class visits, and the school’s newsletter. Adolescents and parents could register and provide their active consent through an online form. For adolescents under 16 years old, parents also provided their informed consent for the participation of their adolescent child. A first batch of participants (N adolescent = 195; N parent = 163) started in November 2019, while we continued to recruit more families to increase the sample size. In February 2020, a second and last batch of participants started (N adolescent = 64; N parent = 25), which led to a total of 259 adolescents and 188 parents. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences of Tilburg University (Nr. EC-2019.65t).

For a full year, adolescents and their parents received 26 bi-weekly questionnaires by e-mail and text message. Both adolescents and parent reported bi-weekly on parenting and adolescent-well-being. The questionnaires took approximately 10 min to complete. Moreover, participants filled out a baseline questionnaire (ca. 35 to 50 extra minutes) and some additional measures every 3 months (plus 10 min). For an overview of the study design and included measures, see http://osf.io/e2jzk.

In (intensive) longitudinal research, compliance is a quality marker and payment is a strong motivator (van Roekel et al., Reference van Roekel, Keijsers and Chung2019; Wrzus & Neubauer, Reference Wrzus and Neubauer2022). Therefore, adolescents received one euro per completed bi-weekly questionnaire, two euro per three-monthly questionnaire, and five euro for the baseline questionnaire. Moreover, adolescents earned five euros extra if they completed the final 5 bi-weekly questionnaires (i.e., surveys 22–26). Additionally, adolescents participated in bi-weekly raffles in which six adolescents won 10 euro. Thus, in total, adolescents could receive a maximum of 51 euro, excluding the raffles.

Missing data

On average, adolescents completed 17.7 of the 26 bi-weekly questionnaires (68%). The majority of the adolescents (58%, n = 148) completed at least 20 of the 26 bi-weekly questionnaires and 31% (n = 80) completed all 26 questionnaires (for a full overview of the compliance, see Table B1 in Appendix B). Across measurement occasions, compliance ranged between 52% to 98%, with 61% at the last measurement (T26). These compliance rates are typical for intensive longitudinal studies with adolescents (van Roekel et al., Reference van Roekel, Keijsers and Chung2019). The missing data were completely at random (MCAR), as indicated by Little’s MCAR test (χ 2 (6) = 11.16, p = .084). All available data were used for the analyses, including partially completed bi-weekly questionnaires, which led to an average of 18.8 observations per adolescent (median = 23, mode = 26). The total number of observations per variable ranged from 4,612 to 4,659.

Instruments

Parental psychological control

To assess adverse parenting, psychological control was bi-weekly measured with adolescent-reports of the Psychological Control-Disrespect Scale (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Xia, Olsen, McNeely and Bose2012). This scale conceptualized psychological control as parental behaviors that disrespect the individuality of the child, such as ridiculing, embarrassing in public, and violation of privacy. Compared to an older version of the scale (Barber, Reference Barber1996), the 2012 version showed to be a stronger predictor of adolescent functioning (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Xia, Olsen, McNeely and Bose2012). Based on the highest factor loadings in a prior study (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Xia, Olsen, McNeely and Bose2012), we included four of the original eight items to decrease participate burden. These four items are: In the last 2 weeks, my parents: (1) ridiculed me or put me down (e.g., by saying I was dumb or useless); (2) embarrassed me in public (e.g., in front of my friends); (3) did not respect me as a person (e.g., not letting me talk, favoring others over me, etc.); and (4) tried to make me feel guilty for something I’ve done or something s/he thinks I should do. We translated these items to Dutch and items were scored from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Our shortened 4-item version had good reliability at both the between-family (ω b = .95) and within-family level (ω w = .74) (Geldhof et al., Reference Geldhof, Preacher and Zyphur2014). Multilevel confirmatory factor analysis (MCFA; Geldhof et al., Reference Geldhof, Preacher and Zyphur2014) indicated a good fit for a one-factor model (CFI = .97, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .03), with standardized factor loadings > .52 at the within-family level and >.74 at the between-family level. Additionally, our 4-item version correlated strongly with the full eight-item scale administered at T1 (r = .90, p = .000).

Parental support

To assess supportive parenting, we included parental emotional support, which was bi-weekly measured using adolescent-reports of a four-item version of the Support subscale of the Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI; Furman & Buhrmester, Reference Furman and Buhrmester1985). A Dutch version has been used and validated in earlier work (Dietvorst et al., Reference Dietvorst, Hiemstra, Hillegers and Keijsers2018; Keijsers et al., Reference Keijsers, Hillegers and Hiemstra2015). The four items are: In the last 2 weeks, how much: (1) did your parent care about you? (2) did your parent appreciate the things you had done? (3) did your parent admire and respect you? and (4) did you care about your parent? Adolescents rated each item on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all; 5 = very often). Parental support was examined separately for the primary and secondary caregiver. In the current study, we focused on parental support of the primary caregiver. The reliability of parental support was good at the between-family (ω b = .96) and within-family level (ω w = .75). The MCFA indicated sufficient fit for a one-factor model (CFI = .91, TLI = .81, RMSEA = .06), with standardized factor loadings above .55 at the within-family level and above .85 at the between-family level.

Adolescent self-esteem

Adolescents rated their self-esteem on the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale Short (RSE-S; Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg1965) every other week. To reduce participant burden, five of the 10 items were selected, which were selected based on the factor loadings in a prior study about a Dutch version of the scale (Franck et al., Reference Franck, De Raedt, Barbez and Rosseel2008). The five item are: In the last 2 weeks: (1) I took a positive attitude towards myself; (2) I felt that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others; (3) I felt that I do not have much to be proud of; (4) I wish I could have had more respect for myself; and (5) I was inclined to feel that I am a failure. The items were rated on a scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). The reliability of our five-item version was excellent at the between-family level (ω b = .90) and reasonable at the within-family level (ω w =.59). MCFA (CFI = .74, TLI = .56, RMSEA = .07) suggested that the two positively formulated items did not load optimally (within-family: .15 and .18, between family: .28 and .55), whereas all three negatively formulated items had high factor loadings (within-family level: .49, .62, and .78; between-family level: .81, .95, and .98). Moreover, our 5-item version correlated strongly with the original 10-item scale which was measured once at T7 (r = .96, p < .001. A higher mean score indicated higher self-esteem.

Adolescent depressive symptoms

Adolescents’ depressive symptoms were bi-weekly measured with a self-report of the Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale Short Form (RADS-2:SF; Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2008). The RADS-SF consists of 10 items, which we translated to Dutch. Adolescents answered each item on a 3-point scale (1 = never; 3 = always). Example items are: In the last 2 weeks: (1) I felt sad; (2) I felt lonely; and (3) I was angry about things. The internal consistency of the scale was good at both the between-family (ω b = .88) and within-family level (ω w = .74). MCFA indicated marginal fit for a unidimensional structure (CFI = .87, TLI = .84, RMSEA = .05). Most standardized factor loadings at the within-family level were between .40 and .68, with one exception of .21 (Item 9: “I was bored”). At the between-family level, standardized factor loadings were between .69 and .94, with one exception of .41 (again Item 9). Earlier work demonstrated that the RADS-2:SF is a reliable and valid measure to screen for depressive symptoms in a community adolescent sample (Ortuño-Sierra et al., Reference Ortuño-Sierra, Aritio-Solana, Inchausti, De Luis, Molina, De Albéniz and Fonseca-Pedrero2017).

Adolescent anxiety symptoms

Anxiety symptoms were self-reported every other week with the Dutch version (Wijsbroek & Hale, Reference Wijsbroek and Hale2005) of the General Anxiety Disorder (GAD) symptoms subscale of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher et al., Reference Birmaher, Khetarpal, Brent, Cully, Balach, Kaufman and Neer1997). The nine items were rated on a 3-point scale from 1 (never) to 3 (always). Example items are: In the last 2 weeks: (1) I was worried about how well I was doing things; (2) I was worried about the future; and (3) I was nervous. The internal consistency of the scale was good at the between-family (ω b = .87) and sufficient at the within-family level (ω w = .71). Moreover, MCFA indicated good fit for a one-factor model of the GAD subscale (CFI = .92, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .04) and sufficiently high factor loadings: between .34 and .66 at the within-family level and between .71 and .97 at the between-family level. Meta-analytic work has shown that the SCARED is a valid self-report to screen for anxiety symptoms in adolescents (Hale et al., Reference Hale, Crocetti, Raaijmakers and Meeus2011).

Adolescent environmental sensitivity

Environmental sensitivity of the adolescent was assessed at T1 with the 12-item Highly Sensitive Child Scale (12-item HSC; Pluess et al., Reference Pluess, Assary, Lionetti, Lester, Krapohl, Aron and Aron2018; Weyn et al., Reference Weyn, Van Leeuwen, Pluess, Lionetti, Greven, Goossens, Colpin, Van Den Noortgate, Verschueren, Bastin, Van Hoof, De Fruyt and Bijttebier2021). The HSC aims at measuring trait environmental sensitivity, specifically sensory processing sensitivity, which is characterized by greater awareness of subtle environmental cues, behavioral inhibition, deeper cognitive processing, higher emotional and physiological responsivity, and ease of overstimulation (Aron et al., Reference Aron, Aron and Jagiellowicz2012; Pluess, Reference Pluess2015). The scale consists of three subscales: Ease of Excitation (5 items, e.g., “I get nervous when I have to do a lot in little time”), Aesthetic Sensitivity (4 items, e.g., “I notice when small things have changed in my environment”), and Low Sensory Threshold (3 items, e.g., “I don’t like loud noises”) (Weyn et al., Reference Weyn, Van Leeuwen, Pluess, Lionetti, Greven, Goossens, Colpin, Van Den Noortgate, Verschueren, Bastin, Van Hoof, De Fruyt and Bijttebier2021). The 12 items of the scale were rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely). In line with earlier work showing good psychometric properties in adolescent samples (Weyn et al., Reference Weyn, Van Leeuwen, Pluess, Lionetti, Greven, Goossens, Colpin, Van Den Noortgate, Verschueren, Bastin, Van Hoof, De Fruyt and Bijttebier2021), the internal consistency in the current sample was good (α = .80). Moreover, a CFA of a bifactor model (i.e., a general sensitivity factor and three group factors) showed a good fit (CFI = .96, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .05), with the general factor loadings between .23 and .72. In the current study we used the total scale score, in which a higher score indicates higher sensitivity to both negative and positive environmental influences.

Preregistered statistical analyses

To estimate parenting effects for each adolescent separately, in addition to the average effects in the sample, Dynamic Structural Equation Modelling (DSEM; Asparouhov et al., Reference Asparouhov, Hamaker and Muthén2018) was employed, which combines the strengths of SEM, multilevel, and N = 1 timeseries. We preregistered our hypotheses and analytical approach (https://osf.io/8egxf/), which was based on similar preregistrations of Beyens et al. (Reference Beyens, Pouwels, van Driel, Keijsers and Valkenburg2021) and Bülow et al. (Reference Bülow, Neubauer, Soenens, Boele, Denissen and Keijsers2022).

First, we checked whether the mean-level structure of the data was stationary. Because measurement occasion explained less than 10% of the variance (0.7% to 2.4%) in adolescent psychological functioning, we assumed stationarity. Subsequently, we estimated six ML-VAR(1) models with Mplus 8.5 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2020), combining 2 parenting variables (psychological control/support) with 3 types of adolescent outcomes (self-esteem/depressive symptoms/anxiety symptoms). At the within-family level, we estimated the concurrent and bidirectional lagged effects as well as the autoregressive effects. At the between-family level, we estimated the variance around the within-family effects (i.e., random effects) and the associations between all random effects and with the random intercepts. To account for unequal time intervals between measurements due to missing data, we set TINTERVAL to 1. Moreover, to account for convergence issues, we simplified two out of six models by removing the between-family associations between the random lagged and autoregressive effects. Still the model with parental psychological control and adolescent anxiety symptoms did not converge, which left us five models to test our hypotheses. An overview of the model specifications and settings for each final interpreted ML-VAR(1) model can be found in Table A1 in Appendix A.

Inference criteria and hypothesis testing

The hypothesized average parenting effects (H1) were derived from fixed within-family lagged effects from parenting to adolescent psychological functioning (significant when Bayesian credible intervals did not include zero). Subsequently, between-family variance around these average within-family lagged effects (H2) was investigated. To investigate which theoretical responsivity patterns would emerge in the sample (H3), we summarized how the five standardized within-family lagged effects combine within an individual adolescent (using STDYX standardization and using the R package “Mplus Automation”; Hallquist & Wiley, Reference Hallquist and Wiley2018). Individual effect sizes were interpreted based on a smallest effect size of interest of .05 (SESOI; Beyens et al., Reference Beyens, Pouwels, van Driel, Keijsers and Valkenburg2021; Lakens et al., Reference Lakens, Scheel and Isager2018), which can be considered a small to medium lagged within-family effect according to recent guidelines (Adachi & Willoughby, Reference Adachi and Willoughby2015; Orth et al., Reference Orth, Meier, Bühler, Dapp, Krauss, Messerli and Robins2022). Hence, we considered effect sizes smaller than .05 as null effects (–.05 > β < .05), effects with a size of β ≥ .05 as positive effects, and effects with a size of β ≤ –.05 as negative effects. Table 1 shows an overview of the inference criteria per responsivity pattern. Finally, to test H4, we compared the subgroups on their mean scores of the HSC, using a two-sided alpha of .05.

Deviations from preregistration

We followed our preregistered plan in almost each step, with the following exceptions. In contrast to our preregistered plan, we included participants who had no over-time variance in their constructs to improve between-family estimates. Moreover, regarding H2, we could not use credibility intervals to test significance of variances because the priors excluded negative values (McNeish & Hamaker, Reference McNeish and Hamaker2019). Instead, we followed recent recommendations to look at the ratio of the standard deviation versus the fixed effect (Bolger et al., Reference Bolger, Zee, Rossignac-Milon and Hassin2019; Bülow, Neubauer, et al., Reference Bülow, Neubauer, Soenens, Boele, Denissen and Keijsers2022). Furthermore, to test H4, we could not compare all found subgroups on their mean score of trait environmental sensitivity because most subgroups were too small (ns ≤ 17). Therefore, we combined several subgroups.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

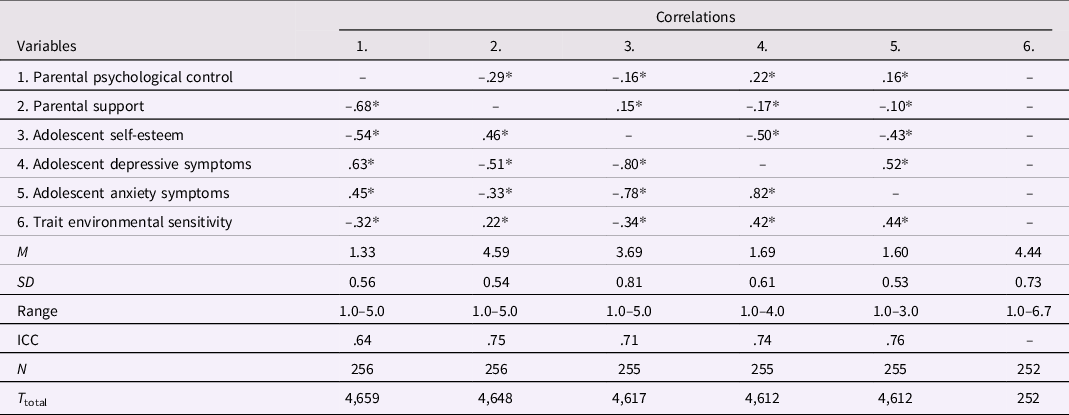

Descriptive statistics and correlations are reported in Table 2. The ICCs indicated that 64% to 76% of the variance in the bi-weekly measures was due to stable between-family variance. The remaining 24% to 36% was due to over-time within-family changes. Within-family (rs = –.43 to .52) and between-family (rs = –.80 to .82) correlations were in the same direction but different in strength. Additionally, with respect to the between-family correlations, adolescents with higher trait levels of environmental sensitivity reported less parental support (r = –.22), more parental psychological control (r = .32), lower self-esteem (r = –.34), and more depressive and anxiety symptoms (rs = .42 and .44), compared to adolescents with lower trait levels.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and within- and between-family level correlations

Note. Correlations above the diagonal line represent within-family correlations and below the diagonal line represent between-family correlations. M = mean. SD = standard deviation. ICC = intraclass correlation. N = sample size. T = number of observations.

*p < .001.

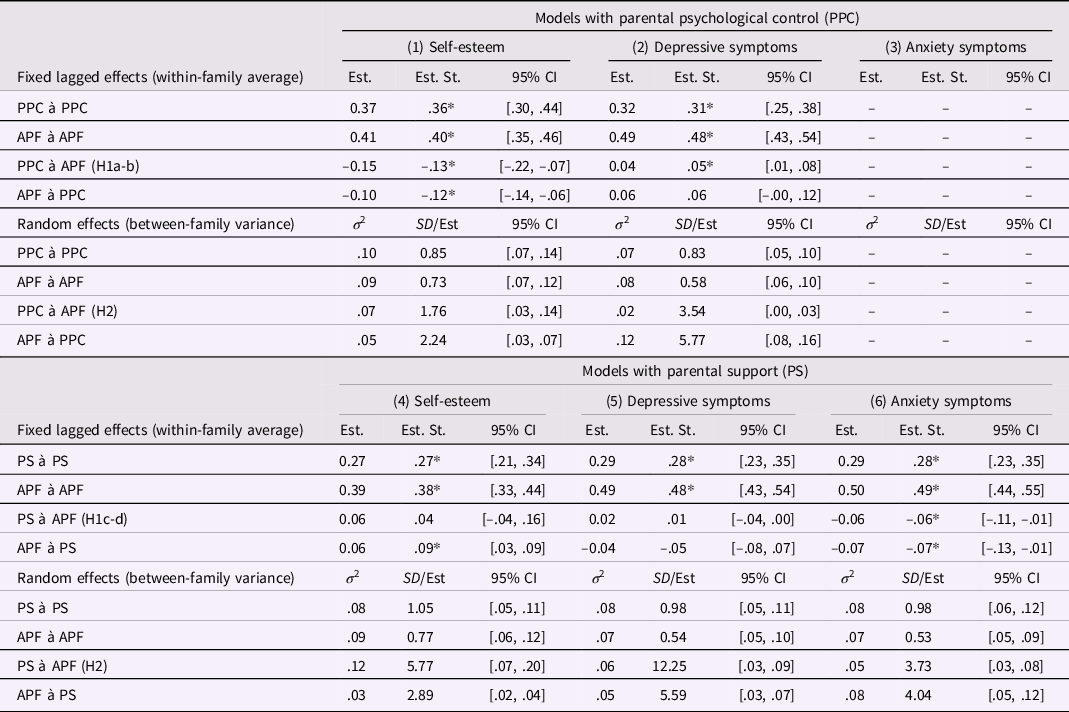

Average effects of parenting on adolescent psychological functioning (H1)

The results of the ML-VAR(1) models demonstrated that three of the five average parenting effects were significant and small in effect size. H1a and H1b were supported: Increased levels of parental psychological control predicted, on average, decreases in adolescent self-esteem (β = –.13) and increases in depressive symptoms (β = .05; see Table 3). In other words, on average, adolescents reported lower self-esteem and more depressive symptoms after having perceived more parental psychological control 2 weeks earlier. However, parental support did not predict changes in adolescents’ self-esteem (rejecting H1c). H1d was partly supported: Although parental support did not predict adolescent depressive symptoms, it did predict fewer anxiety symptoms (β = –.06).

Table 3. DSEM analyses with parenting and adolescent psychological functioning (APF)

Note. Parameters whose 95% credible interval does not contain zero are shown with an asterisk. Model with parental psychological control and adolescent anxiety symptoms did not converge. PPC = parental psychological control. PS = parental support. APF = adolescent psychological functioning. Est = unstandardized estimate. Est. St. = standardized estimate (i.e., STDYX standardization). P = one-sided p-value. 95% CI = Bayesian Credible Intervals. SD = standard deviation. SD/Est. = standard deviation fixed effect ratio, to inspect whether variance is meaningful, with a criterium of ≥ 0.25 (Bolger et al., Reference Bolger, Zee, Rossignac-Milon and Hassin2019). Not all parameter estimates are reported here and for full output see (https://osf.io/8egxf/?view_only=c154523c7f73468b81cd1b5cee180279).

All lagged parenting effects were controlled for the reverse lagged effect from adolescent psychological functioning to parenting (see Table 3). On average, adolescent self-esteem had a significant negative effect on parental psychological control (β = –.12) and a positive effect on parental support (β = .09), and adolescent anxiety symptoms had a significant negative effect on parental support (β = –.07).

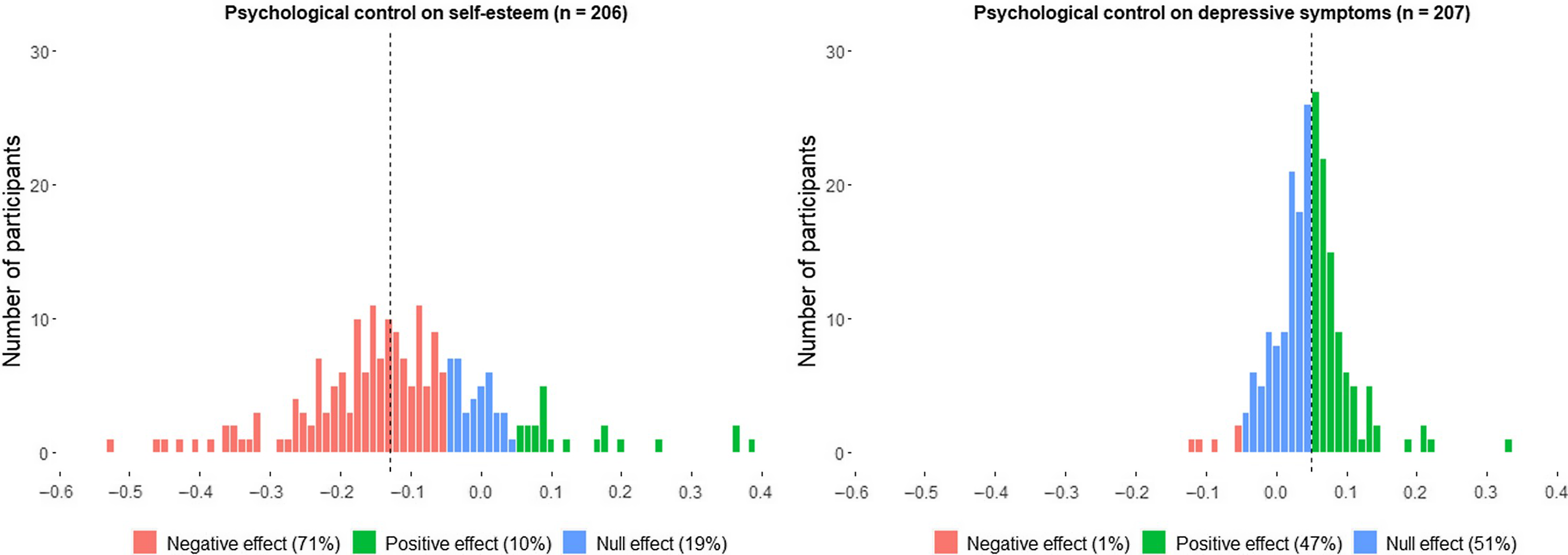

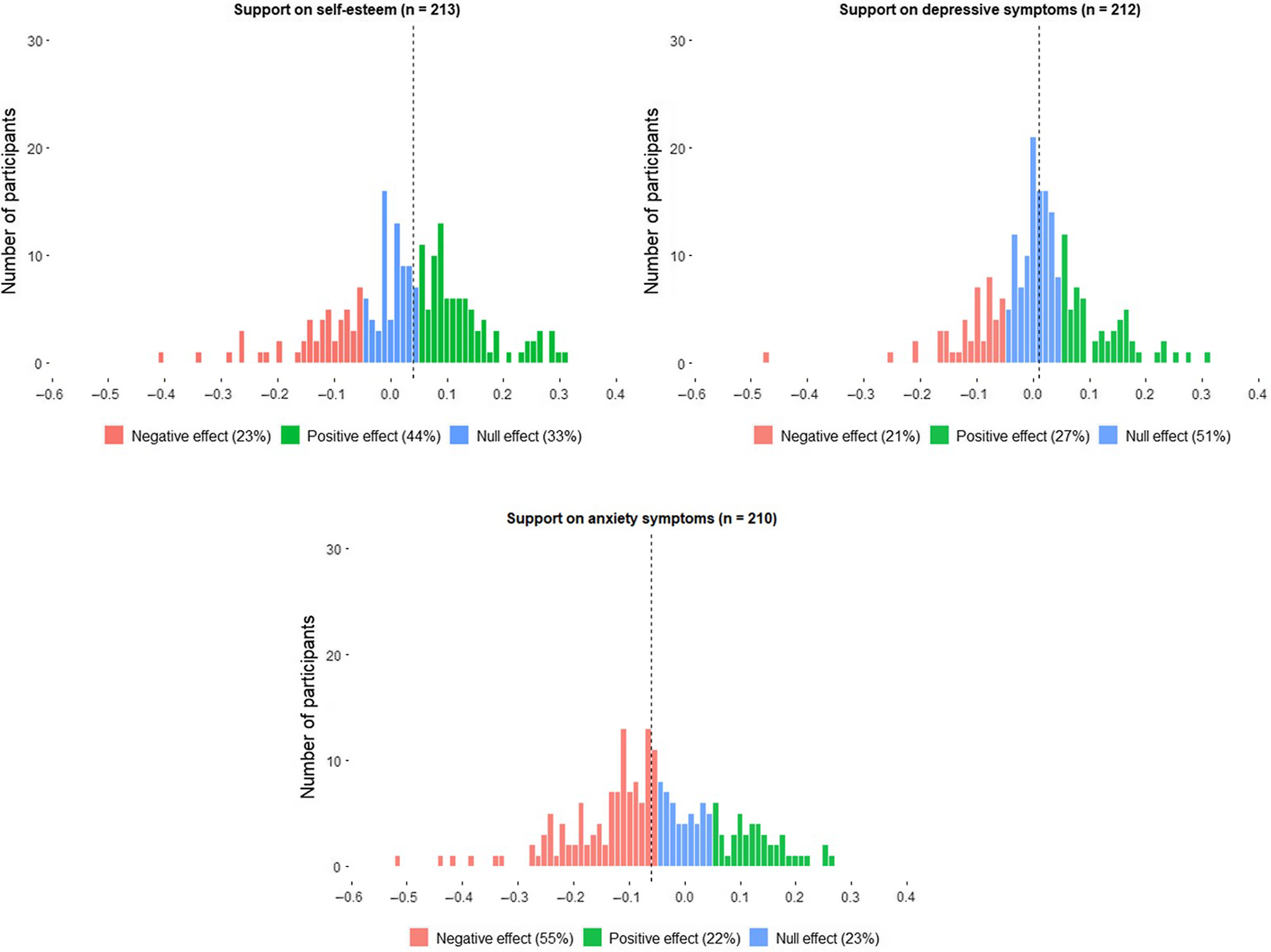

Effect heterogeneity: differences between families in parenting effects (H2)

Each of the within-family effects showed meaningful variance as indicated by a standard deviation fixed effect of at least ratio of 0.25 (see Table 3; Bolger et al., Reference Bolger, Zee, Rossignac-Milon and Hassin2019). Thus, as expected (H2), adolescents varied substantially in how perceived changes in parenting predicted subsequent changes in their psychological functioning. For example, individual effect sizes of the lagged effect from parental support to depressive symptoms ranged from β = –.48 to .31 across families (see Figure 2). For 21%, this effect was negative (β ≤ –.05), as expected (see H1d). Others (51%) had a null effect (β between –.05 and .05), and 27% had a positive lagged effect (β ≥ .05). This parenting effect heterogeneity is illustrated in Figures 3 and 4, showing that the strength and sign of the effects differed between families.

Figure 2. Parenting effect heterogeneity for psychological control: distribution of individual effect sizes. Note. Dashed line is the average within-family effect (see Table 3). Effect sizes with self-esteem as outcome ranged from β = –.53 to .38 and with depressive symptoms from β = –.12 to .33.

Figure 3. Parenting effect heterogeneity for parental support: distribution of individual effect sizes. Note. Dashed line is the average within-family effect (see Table 3). Effect sizes with self-esteem as outcome ranged from β = –.41 to β = .33, with depressive symptoms from β = –.48 to β = .31, and with anxiety symptoms from β = –.51 to β = .27

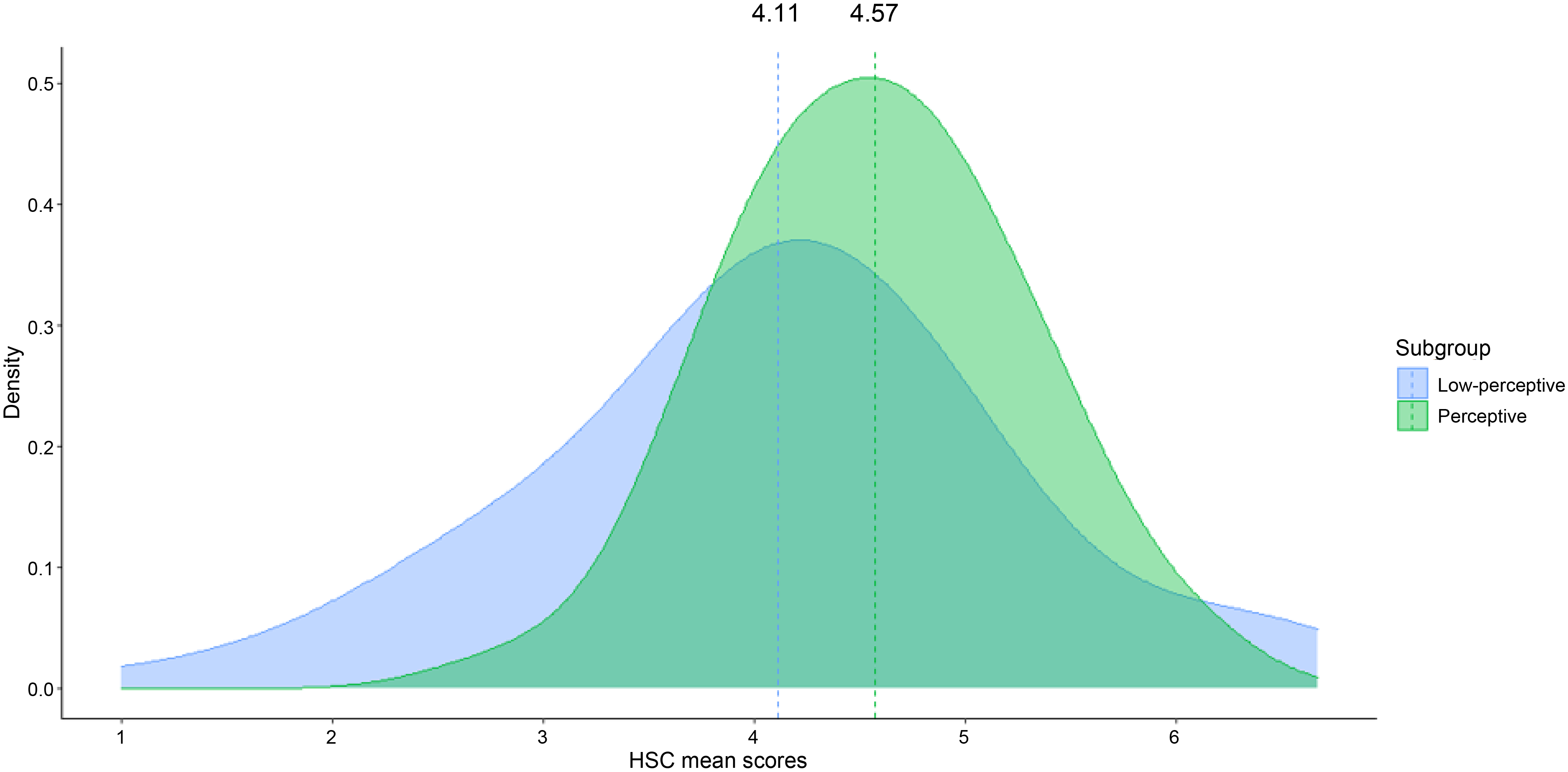

Figure 4. Distribution of mean scores of the highly sensitive child scale (HSC) for low-perceptive and perceptive adolescents. Note. Low-perceptive adolescents (n = 70) did not perceive bi-weekly changes in parenting (and some also in their psychological functioning). Perceptive adolescents (n = 182) perceived and were affected (in all possible manners) by these changes in parenting.

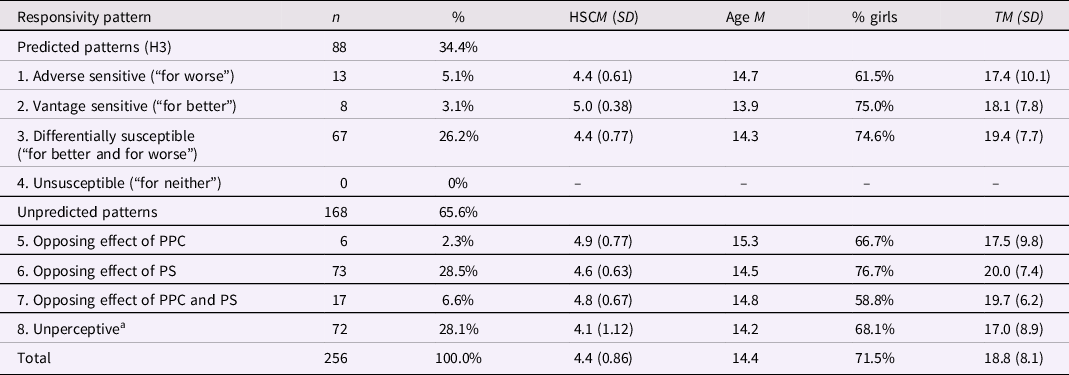

Coexisting responsivity patterns (H3)

The study’s main hypothesis was that theoretical responsivity patterns (i.e., adverse sensitive, vantage sensitive, differentially susceptible, and unsusceptible pattern) would coexist in the sample and thus apply to different subgroups of adolescents. Although the results supported this hypothesis of coexisting responsivity patterns, we also found unexpected patterns. An overview of all patterns and their descriptive statistics is shown in Table 4 (for a more detailed description see Table C1 in Appendix C).

Table 4. Overview of responsivity patterns in the sample

Note. n = number of participants. HSC = Highly Sensitive Child Scale. M = mean. SD = standard deviation. T = number of bi-weekly observations.

a Of the 72 adolescents, 2 showed changes in parenting but not in their psychological functioning.

Around one-third of the sample showed a predicted responsivity pattern: 5% was adverse sensitive (n = 13), 3% vantage sensitive (n = 8) and 26% differentially susceptible (n = 67). However, no adolescent showed the hypothesized unsusceptible pattern. Unexpectedly, around one in four adolescents (n = 73, 29%) demonstrated a negative effect of parental support on their psychological functioning (see “Opposing effect of PS” in Table 4), a small minority (n = 6; 2%) reported better psychological functioning following more psychologically controlling parenting or reported both unexpected responses (n = 17, 7%). Finally, 28% (n = 72) did not perceive over-time changes in parenting and/or their psychological functioning (see “Unperceptive” in Table 4) and could not be assigned a responsivity pattern for this reason.

Trait environmental sensitivity and responsivity patterns (H4)

Because the (theorized and expected) unsusceptible adolescents were not found in our sample, and the other subgroups were too small to allow comparisons (ns ≤ 17; see Table 4), we combined subgroups of adolescents. When comparing differentially susceptible adolescents (M = 4.41; n = 66) to all other adolescents (M = 4.45; n = 186), no differences in trait levels of environmental sensitivity were found, as measured with the HSCFootnote 3 , W = 5743.5, p = .439. We ran exploratory models to further investigate the link of trait environmental sensitivity to within-family parenting effects.

Exploratory analyses (not preregistered)

Potentially, trait environmental sensitivity could be related to how strongly adolescents are affected by perceived changes parenting (i.e., absolute effect sizes), regardless of their pattern of effects. However, we found no compelling evidence for this; of the five absolute effect sizes, only one parenting-outcome effect size significantly correlated with trait levels of environmental sensitivity (see Table D1 in Appendix D). Specifically, adolescents who scored higher on trait environmental sensitivity reported stronger responses to changes in parental support in terms of their depressive symptoms, indicated by a positive correlation between the HSC and the individual effect sizes of parental support on depressive symptoms (r = .20, p = .015).

Another plausible explanation might be that trait environmental sensitivity reflects individual differences in the ability to perceive subtle changes in parenting rather than responsivity (Pluess, Reference Pluess2015). As depicted in Figure 5, exploratory analyses indeed showed that unperceptive adolescents who did not perceive bi-weekly changes in parenting (n = 70, M = 4.11) scored lower on trait environmental sensitivity than adolescents who did perceive changes (n = 182, M = 4.57), t = –3.19, p = .002, d = –.49. In support of this idea, adolescents who scored higher on trait environmental sensitivity perceived greater over-time changes in parenting, as indicated by significant correlations between the within-family standard deviation of parental psychological control or support and trait environmental sensitivity (rs = .21 and .23, p ≤ .001). Together, these exploratory findings indicate that adolescents scoring higher on trait environmental sensitivity tended to perceive (greater) over-time changes in parenting but were not more responsive to them.

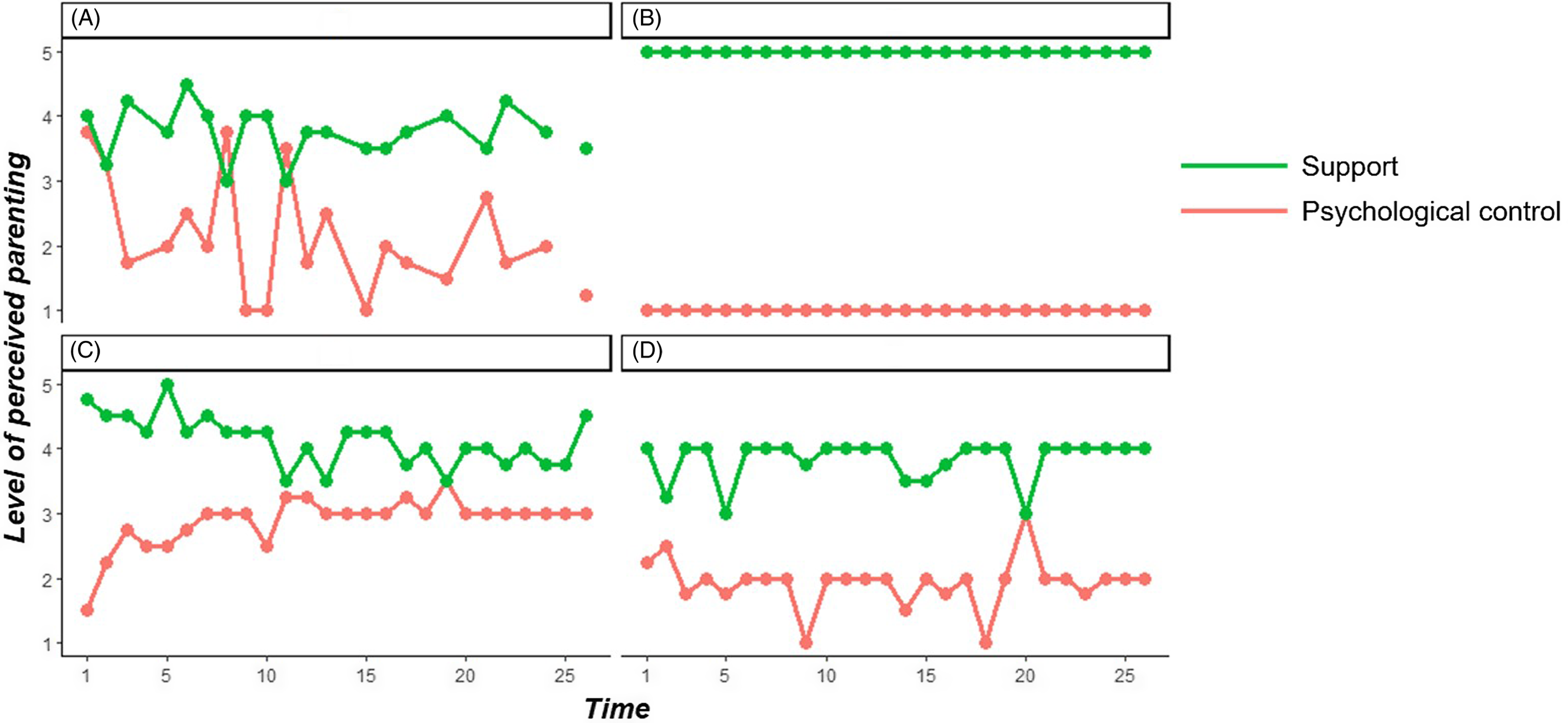

Figure 5. Perceived parenting fluctuates in most families: data of four participants. Note. Time represents a bi-weekly timescale

Sensitivity analyses

Multi-informant model with parent-reported parenting (preregistered)

To replicate main findings (H1–H4) across multiple informants, we conducted the analyses with parent-reported parenting and adolescent-reported psychological functioning (subsample of n = 177; for sample and descriptive statistics see Table E1 in Appendix E). Although, on average, adolescent’s psychological functioning could not be predicted by parent-reported parenting (H1a–d not confirmed, see Table E2), again all lagged effects showed meaningful effect heterogeneity (H2 confirmed; for sample distributions, see Table E3). With respect to the responsivity patterns, we did find all four predicted responsivity patterns, including the unsusceptible pattern (H3 confirmed; see Table E4), in which the group size of the patterns ranged from 9% to 19%. Agreement between responsivity patterns based on parent-reported versus adolescent-reported parenting ranged from 0% (adverse sensitive and unsusceptible patterns) to 36% (unperceptive pattern) (for more details see, Table E5). Similar as in the main analyses, H4 was not confirmed, as adolescents with a differentially susceptible pattern based on parent-reported parenting did not show higher trait levels of environmental sensitivity than the other adolescents, t (172) = –0.04, p = .965.

Concurrent effects (exploratory)

As exploration, we tested whether the main findings (i.e., lagged effects) would replicate with concurrent parenting associations, produced by ML-AR(1) models including adolescent-reported parenting as a time-varying covariate (see Table F1 in Appendix F). Different than the main findings, all hypothesized average parenting effects were found with the concurrent models (H1a-d confirmed; see Table F2 in Appendix F). Moreover, similar as the main findings, all parenting associations showed meaningful between-family variance (H2 confirmed), although effect heterogeneity was smaller. Regarding the responsivity patterns, we found similar patterns for the concurrent associations as for the lagged effects (H3 confirmed; for full overview, see Table F3), including no unsusceptible adolescents. Nevertheless, based on concurrent effects, the majority of the sample (61% vs. 26% with lagged effects) was classified as differential susceptible and a small percentage as adverse sensitive (2%) and vantage sensitive (1%). Notably, 93% of adolescents who had a differentially susceptible pattern with lagged effects had a similar pattern with concurrent effects (for a detailed comparison, see Table F4). However, 63 of the 156 adolescents who had differentially susceptible pattern with concurrent models showed an unexpected responsivity pattern (i.e., opposing parenting effects) with lagged models. Moreover, fewer adolescents showed opposing parenting effects (36% vs. 66% with lagged effects). Furthermore, again H4 was not confirmed, as differentially susceptible adolescents did not differ in trait environmental sensitivity compared to all others, W = 8358, p = .150.

Additional sensitivity analyses (exploratory)

To further assess the robustness of the findings concerning the responsivity patterns, we additionally conducted sensitivity analyses. We explored to what extent: (a) the classification was influenced by the effect size cut-off by raising the cut-off to .10 (see results in Table G1 in Appendix G); (b) the classification was influenced by participants who had five or less observations (n = 23; see Table G2); and (c) the estimation of individual effect sizes was influenced by the inclusion of participants who had no over-time variation (n = 72; see Table G3). Although group sizes slightly varied across analyses, we found the same predicted and unpredicted responsivity patterns as in the main analyses, in which differential susceptible (20% to 28%), “opposing effect of parental support” (24% to 30%), and unperceptive (25% to 28%) were again the three largest subgroups. Hence, we conclude that the main findings were robust across the abovementioned methodological factors as the results remained in line with our main hypothesis that different responsivity patterns coexist.

Summary of predicted responsivity patterns (H3): main analysis versus sensitivity analyses

Across studied time interval (lagged vs. concurrent) and informant (adolescent vs. parent), differences emerged in the sample distribution of the predicted responsivity patterns (H3). That is, 2% to 14% of adolescents demonstrated an adverse sensitive pattern, 1% to 19% a vantage sensitive pattern, 13% to 61% a differential susceptible pattern, and 0% to 18% an unsusceptible pattern. Moreover, in the adolescent-reported models, considerably more adolescents were classified as differential susceptible (26% to 61%) than adverse sensitive (2% to 5%) or vantage sensitive (1% to 3%), especially in the concurrent models. In the parent-reported parenting models, these predicted patterns were more equally distributed in the sample (9% to 19%). Furthermore, although we found little evidence for the predicted unsusceptible pattern with adolescent-reported data, we did find this pattern with parent-reported parenting in 18% of the sample. Notwithstanding the differences, we repeatedly found that different adolescents demonstrated different predicted (but also unpredicted) responsivity patterns.

Discussion

One of the ongoing debates in the parenting literature is the extent to which parenting has universal or heterogeneous effects upon child functioning (Grusec, Reference Grusec, Kerr and Engels2008; Rohner et al., Reference Rohner, Khaleque and Cournoyer2005; Soenens et al., Reference Soenens, Vansteenkiste and Van Petegem2015). Environmental sensitivity models assume parenting effect heterogeneity, such that children’s responses to parenting depend on their general sensitivity to environmental influences (Greven et al., Reference Greven, Lionetti, Booth, Aron, Fox, Schendan, Pluess, Bruining, Acevedo, Bijttebier and Homberg2019; Pluess, Reference Pluess2015). Three theoretical models (see Figure 1) posit a subgroup of highly sensitive children who are more responsive to either: (1) adverse parenting (“for worse”, diathesis-stress model; Monroe & Simons, Reference Monroe and Simons1991; Zuckerman, Reference Zuckerman1999); or (2) supportive parenting (“for better”, vantage sensitivity model; Pluess, Reference Pluess2017); or (3) to both (“for better and for worse”, differential susceptibility model; Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van Ijzendoorn2007; Belsky & Pluess, Reference Belsky and Pluess2009). In all three models, highly responsive children are compared against a subgroup of non-responsive unsusceptible children. In the current study, we tested the “coexisting responsivity patterns hypothesis” among adolescents, proposing that the models complement each other and each explain a different subgroup in the population (Pluess, Reference Pluess2015; Pluess & Belsky, Reference Pluess and Belsky2012, Reference Pluess and Belsky2013). We applied a preregistered within-family approach, using intensive longitudinal (bi-weekly) data. By applying this approach, we could estimate parenting effects for each individual adolescent in the sample separately, which enabled us to assess individual differences in parenting effects. Our main findings indeed demonstrate evidence that the different responsivity patterns coexist. Yet, a “for better and for worse” responsivity pattern was more common than a “for worse” or “for better” pattern. However, no adolescent appeared unsusceptible. Instead, a subgroup appeared not responsive because they did not perceive any changes in parenting, who scored meaningfully lower on trait environmental sensitivity (i.e., sensory processing sensitivity) than all others. Finally, a substantive number of adolescents responded in opposite way from what is expected from universal parenting theories (Rohner et al., Reference Rohner, Khaleque and Cournoyer2005; Soenens et al., Reference Soenens, Deci, Vansteenkiste, Wehmeyer, Little, Lopez, Shogren and Ryan2017), whom did not fit in hypothesized responsivity patterns.

Effect heterogeneity: parenting effects differ between families

At the core of environmental sensitivity models (Greven et al., Reference Greven, Lionetti, Booth, Aron, Fox, Schendan, Pluess, Bruining, Acevedo, Bijttebier and Homberg2019; Pluess, Reference Pluess2015) is effect heterogeneity (Bolger et al., Reference Bolger, Zee, Rossignac-Milon and Hassin2019): individuals do not similarly respond to similar environmental influences. In line with some first empirical studies (Bülow, van Roekel, et al., Reference Bülow, van Roekel, Boele, Denissen and Keijsers2022; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Verkuil, van Houtum, Wever and Elzinga2021), there was indeed meaningful variation around all average within-family parenting effects, both around significant and nonsignificant average effects. When zooming into the individual effect sizes, effect sizes varied in both size and sign across the adolescents in our study. Parenting effect heterogeneity was replicated with parent-reported parenting and concurrent associations (though heterogeneity was larger in lagged effects). Hence, although the links between the studied parenting dimensions and adolescent outcomes are well established at the group level (Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2017; Pinquart & Gerke, Reference Pinquart and Gerke2019), effects at the individual level suggest otherwise. How adolescents respond to parenting influences is heterogeneous, just as many other psychological processes across the lifespan (Bolger et al., Reference Bolger, Zee, Rossignac-Milon and Hassin2019; Richters, Reference Richters2021). As such, this study adds to an emerging body of literature that stresses how average effect sizes do not describe each individual and that ignoring heterogeneity may lead to invalid conclusions (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Tipton and Yeager2021; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Medaglia and Jeronimus2018; Grice et al., Reference Grice, Medellin, Jones, Horvath, McDaniel, O’lansen and Baker2020; Hamaker, Reference Hamaker, Mehl and Conner2012).

For better, for worse, for both, and for neither: coexisting responsivity patterns

In earlier work, the diathesis-stress, vantage sensitivity, and differential susceptibility model have been mostly theorized and tested as competing models (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van Ijzendoorn2007, Reference Belsky, Pluess and Widaman2013; Roisman et al., Reference Roisman, Newman, Fraley, Haltigan, Groh and Haydon2012). Empirical studies have found support for each model, with inconsistencies in findings being related to the studied parenting practice, child outcome, developmental period, and sensitivity marker, for example (Rabinowitz & Drabick, Reference Rabinowitz and Drabick2017; Rioux et al., Reference Rioux, Castellanos-Ryan, Parent and Séguin2016; Slagt et al., Reference Slagt, Dubas, Deković and van Aken2016). One explanation for these inconsistent findings is that all distinct theorized subgroups of adverse sensitive, vantage sensitive, and differentially susceptible adolescents coexist in the population. Indeed, Pluess (Reference Pluess2015) theorizes that individuals vary in their sensitivity to adverse and/or supportive influences, which can again manifest in some individuals being highly responsive to either unsupportive or supportive influences, or to both influences. Our study is the first, to our knowledge, to assess whether different responsivity-to-parenting patterns coexist.

In support of this hypothesis, around one third of the 256 adolescents in the sample showed one of the theorized responsivity patterns. Specifically, 5% appeared adverse sensitive, 3% vantage sensitive, and 26% differentially susceptible. Although these proportions varied across sensitivity analyses, overall the findings suggest that the three different environmental sensitivity models may coexist. Yet, more adolescents seemed responsive to both adverse and supportive parenting than to only one of the two. Hence, as suggested earlier by scholars, determinants of heightened environmental sensitivity (e.g., temperamental traits or genetic variants) might indeed mostly result in responsivity to both positive and negative parenting influences (Boyce & Ellis, Reference Boyce and Ellis2005; Pluess, Reference Pluess2015).

Moreover, in all three environmental sensitivity models, responsive adolescents (either adverse, vantage or differentially susceptible) are theoretically compared against a subgroup of non-responding unsusceptible adolescents (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van Ijzendoorn2007; Belsky & Pluess, Reference Belsky and Pluess2009; Slagt et al., Reference Slagt, Dubas, Deković and van Aken2016). However, unexpectantly, no adolescent in the sample appeared unsusceptible (i.e., not responding to perceived changes in parenting). Instead, 28% appeared not responsive because they did not perceive changes in parenting (for an example see participant B in Figure 5) and scored lowest on trait environmental sensitivity (i.e., sensory processes sensitivity). These findings highlight the differentiation between sensitivity and responsivity, and indeed suggest that low sensory processing sensitivity could lead to low responsivity to the environment because of an inability to perceive subtle changes (Pluess, Reference Pluess2015).

To further understand our findings, it is helpful to link them to so-called proposed “weak” and “strong” versions of environmental sensitivity models (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Pluess and Widaman2013; Jolicoeur-Martineau et al., Reference Jolicoeur-Martineau, Belsky, Szekely, Widaman, Pluess, Greenwood and Wazana2019). Weak versions assume continuous differences between individuals in responsiveness, with some being more responsive than others. Strong versions, in contrast, describe a clear dichotomy with individuals either being responsive or not at all. In line with weak versions: perceived changes in parenting predicted changes in psychological functioning in all adolescents, although some appeared more strongly affected than others. Nonetheless, we also found a distinction between responsive and unresponsive adolescents, which is in line with strong versions. Our findings further illuminate that the unresponsive adolescents in our sample did not perceive any over-time changes in parenting (labeled as unperceptive, e.g., individual B in Figure 5). This unpredicted unperceptive responsivity pattern – not responding because not perceiving – differed from our predicted subgroup of unsusceptible adolescents (for illustration, see Figure 1), who we conceptualized as individuals who not respond to perceived changes in parenting. Hence, our findings indicate that weak and strong versions of environmental models can perhaps be integrated: Whereas a distinct subgroup of individuals do not perceive and therefore not respond to environmental influences, others perceive environmental changes and respond to these environmental influences in varying degrees.

To assess whether the main findings replicate to immediate responsivity, we also explored concurrent associations. In line with previous work (Bülow, van Roekel, et al., Reference Bülow, van Roekel, Boele, Denissen and Keijsers2022), concurrent associations were less heterogeneous than lagged parenting effects (i.e., from perceived parenting to adolescent functioning). Whereas the concurrent associations provide predominantly evidence for a differential susceptible responsivity pattern (Belsky & Pluess, Reference Belsky and Pluess2009), the lagged parenting effects were in line with our hypothesis that different responsivity patterns coexist (and thereby possibly different sensitivity types, see Pluess, Reference Pluess2015). In other words, perceived parenting and psychological functioning seemed to co-fluctuate similarly within individual adolescents. However, when disentangling the direction of effects to assess “what comes first” (Hamaker et al., Reference Hamaker, Kuiper and Grasman2015; Keijsers, Reference Keijsers2016), adolescents indeed seemed to respond differently to preceding changes in perceived parenting in terms of their psychological functioning. Our findings thus highlight the necessity to also consider lagged effects when aiming to unraveling heterogeneity in parenting effects.

In addition to adolescent-reported parenting, we also explored adolescents’ responses to changes in parent-reported parenting. In line with prior work (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Benner, Kim, Chen, Spitz, Shi and Beretvas2019; Janssen, Verkuil, et al., Reference Janssen, Verkuil, van Houtum, Wever and Elzinga2021), we found differences in adolescents’ and parents’ reports of parenting. For instance, some adolescents had perceived no changes in parenting while their parent did report changes. Moreover, adolescents’ reports of parenting were more often predictive of their psychological functioning than parent-reported parenting (see also Bülow, Neubauer, et al., Reference Bülow, Neubauer, Soenens, Boele, Denissen and Keijsers2022), which is in accordance with developmental theories emphasizing that subjective experiences are the driving forces of well-being (Rohner, Reference Rohner2016; Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2010; Soenens et al., Reference Soenens, Vansteenkiste and Van Petegem2015). Hence, although we did find similar co-existing responsivity patterns, thereby again confirming our main hypothesis, the classification of adolescents’ responsivity patterns differed between informants. As environmental sensitivity theories posit that individual differences in sensitivity (i.e., how stimuli are perceived and processed) are accountable for differences in responsivity patterns (Greven et al., Reference Greven, Lionetti, Booth, Aron, Fox, Schendan, Pluess, Bruining, Acevedo, Bijttebier and Homberg2019; Pluess, Reference Pluess2015), our main findings based on self-reports may be more meaningful in light of environmental sensitivity theories.

Some are more sensitive in perceiving changes in parenting

One of the key elements of the environmental sensitivity models is that effect heterogeneity can be explained by individual differences in trait environmental sensitivity. We examined environmental sensitivity as sensory processing sensitivity, which is characterized by greater awareness of subtle environmental cues, behavioral inhibition, deeper cognitive processing, higher emotional and physiological responsivity, and ease of overstimulation (Aron et al., Reference Aron, Aron and Jagiellowicz2012; Pluess, Reference Pluess2015). Due to limited subgroup sizes and no observed unsusceptible adolescents in our main findings, we were unable to test whether differentially susceptible adolescents demonstrated the highest trait levels of environmental sensitivity. Instead, we checked how the five parenting effects were related to trait environmental sensitivity. The results showed that only the effect of parental support on depressive symptoms was stronger for adolescents who reported higher trait levels of environmental sensitivity, which relates to prior work suggesting that more sensitive children in families with low-quality parenting are at higher risk for internalizing problems (Lionetti et al., Reference Lionetti, Klein, Pastore, Aron, Aron and Pluess2021, Reference Lionetti, Spinelli, Moscardino, Ponzetti, Garito, Dellagiulia, Aureli, Fasolo and Pluess2022). In light of interventions targeting parenting, it is crucial to further identify which adolescents are more responsive to perceived changes in adverse parenting, supportive parenting, or to both.

Because we unexpectantly observed adolescents who perceived parenting as stable during the full study year, we looked at this subgroup in more detail. Findings revealed that this subgroup showed lower trait levels of environmental sensitivity compared to adolescents who perceived changes in parenting and seemed affected by it – in all possible ways. Overall, our findings indicate that individual differences in trait levels of environmental sensitivity reflect differences in the ability to perceive subtle environmental changes and not per se differences in responsivity to environmental changes (Aron et al., Reference Aron, Aron and Jagiellowicz2012; Pluess, Reference Pluess2015).

Unpredicted responsivity pattern: when supportive parenting is unsupportive

One intriguing and unexpected finding was that 37% of the sample responded contrary to parenting theories (Soenens et al., Reference Soenens, Deci, Vansteenkiste, Wehmeyer, Little, Lopez, Shogren and Ryan2017) and therefore did not match with one of the hypothesized responsivity patterns. Most of these adolescents reported lower psychological functioning after parental support increased 2 weeks earlier. With the appearance of intensive longitudinal work on parenting, such unexpected effects of parental support have been reported in a recent experience sampling study (Bülow, van Roekel, et al., Reference Bülow, van Roekel, Boele, Denissen and Keijsers2022) but not consistently in daily diary studies (Bülow, Neubauer, et al., Reference Bülow, Neubauer, Soenens, Boele, Denissen and Keijsers2022; Janssen, Elzinga, et al., Reference Janssen, Elzinga, Verkuil, Hillegers and Keijsers2021).

One explanation for these unexpected findings is that parental support can backfire in some families, for instance based on characteristics of the parent, the adolescent, or the parent-adolescent relationship (Janssen, Elzinga, et al., Reference Janssen, Elzinga, Verkuil, Hillegers and Keijsers2021; Rote et al., Reference Rote, Olmo, Feliscar, Jambon, Ball and Smetana2020). For some, supportive parenting might be experienced as overinvolvement, hindering their psychological functioning by age-inappropriate restriction of their autonomy, for instance (Padilla-Walker & Nelson, Reference Padilla-Walker and Nelson2012; Rote et al., Reference Rote, Olmo, Feliscar, Jambon, Ball and Smetana2020; Schiffrin et al., Reference Schiffrin, Liss, Miles-McLean, Geary, Erchull and Tashner2014). Likewise, less support and warmth from parents may be experienced as granting more independence and less intrusion (Dietvorst et al., Reference Dietvorst, Hiemstra, Hillegers and Keijsers2018; Van Petegem et al., Reference Van Petegem, Soenens, Vansteenkiste and Beyers2015), which could actually promote better functioning. Earlier work suggests that mainly adolescents who score higher on depressive symptoms might be more vulnerable for the negative effects of parental support (Janssen, Elzinga, et al., Reference Janssen, Elzinga, Verkuil, Hillegers and Keijsers2021). However, no moderating effects have been found for other adolescent characteristics, such as age, gender, and neuroticism (Boele et al., Reference Boele, Nelemans, Denissen, Prinzie, Bülow and Keijsers2022; Bülow, Neubauer, et al., Reference Bülow, Neubauer, Soenens, Boele, Denissen and Keijsers2022; Janssen, Elzinga, et al., Reference Janssen, Elzinga, Verkuil, Hillegers and Keijsers2021). Thus, parenting effects might thus not always be universal (Grusec, Reference Grusec, Kerr and Engels2008), but under which circumstances and for whom needs to be unraveled.

Responsivity to parenting might be outcome specific

A question that recently gained more attention is whether environmental sensitivity is specific to the outcome (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van Ijzendoorn2007, Reference Belsky, Zhang and Sayler2021). To account for this, we included different outcomes, both positive and negative indicators of adolescents’ psychological functioning (Keyes, Reference Keyes, Bauer and Hämmig2014; Ryff et al., Reference Ryff, Dienberg Love, Urry, Muller, Rosenkranz, Friedman, Davidson and Singer2006). Hence, our responsivity patterns were based on a combination of three adolescent outcomes. Despite that the adolescent outcomes correlated within the same individuals, the two parenting practices did not predict all three outcomes in all adolescents. To illustrate, 12 of the 67 differentially susceptible adolescents were affected in a for-better-and-for-worse manner in all three outcomes, whereas the others were affected in one or two outcomes. Hence, our results suggest that the specific outcome of parenting might still depend on the person. Even though future studies need to replicate the found responsivity patterns to parenting, both theorized and unexpected patterns, findings emphasize the importance of considering multiple outcomes. This corresponds to the broader multifinality principle in developmental psychology that the same influence can lead to different outcomes in different children (Cicchetti & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch1996).

Limitations and future research

While being one of the first within-family study to assess heterogeneity in parenting effect in such detail, it is not without limitations. First, the number of assessments per person was insufficient to test for N = 1 significance (Voelkle et al., Reference Voelkle, Oud and Oertzen2012), and therefore we assigned adolescents to different responsivity patterns based on a subjective effect size cut-off (β ≥ .05) (Beyens et al., Reference Beyens, Pouwels, van Driel, Keijsers and Valkenburg2021; Lakens et al., Reference Lakens, Scheel and Isager2018; Orth et al., Reference Orth, Meier, Bühler, Dapp, Krauss, Messerli and Robins2022) rather than significance levels. Hence, the hypothesis was tested with descriptive data. Methods that can estimate data-driven subgroups, for instance DSEM-mixture models (Asparouhov et al., Reference Asparouhov, Hamaker and Muthén2017), Markov modelling (de Haan-Rietdijk et al., Reference de Haan-Rietdijk, Kuppens, Bergeman, Sheeber, Allen and Hamaker2017), or Subgrouping Group Iterative Multiple Model Estimation (S-GIMME; Lane et al., Reference Lane, Gates, Pike, Beltz and Wright2019), is a promising direction for future research to replicate current findings and further study individual differences in parenting processes. Relatedly, the sample-level reliabilities of the family-specific lagged effects were rather low: between .43 and .53 (with one exception of .28) (within-person coupling reliability (WPCR index); see Neubauer et al., Reference Neubauer, Voelkle, Voss and Mertens2020), which might have attenuated the statistical power to detect parenting effects within each individual family. A higher number of assessments per person may lead to more reliable and detectable individual estimates (Voelkle et al., Reference Voelkle, Oud and Oertzen2012), and therefore, findings need replication with higher-powered intensive longitudinal studies to optimally apply an idionomic approach (i.e., detecting subgroups by using idiographic, N = 1 data; Chaku & Beltz, Reference Chaku, Beltz, Gilmore and Lockman2022; Sanford et al., Reference Sanford, Ciarrochi, Hofmann, Chin, Gates and Hayes2022). Nonetheless, prior work has found no substantial differences in the sign (i.e., positive or negative) and strength of individual parenting effect sizes when 25, 50, or 100 data points were analyzed (Bülow, Neubauer, et al., Reference Bülow, Neubauer, Soenens, Boele, Denissen and Keijsers2022).

Second, the sample included a homogenous community adolescent sample, with the majority being female and following higher secondary education tracks. Therefore, there is a possibility that some subgroups might be underrepresented in our sample. For instance, highly sensitive individuals are more prevalent in clinical samples (Greven et al., Reference Greven, Lionetti, Booth, Aron, Fox, Schendan, Pluess, Bruining, Acevedo, Bijttebier and Homberg2019). Future studies with larger, more heterogeneous (e.g., clinical) samples are required to replicate (the size of) coexisting responsivity patterns. Moreover, the question remains whether the found responsivity patterns are specific to adolescence. The substantial subgroup who did not perceive changes in parental behavior might consist of adolescents who spend little time with their parents, which is an important developmental task in adolescence (Larson et al., Reference Larson, Richards, Moneta, Holmbeck and Duckett1996). Future research should investigate to what extent responsivity-to-parenting patterns replicate to other developmental periods such as childhood.