Introduction

The state wields enormous power over the liberty of the individual through the Mental Health Act 1983. In other areas of the law, particularly criminal justice, such power draws on community legitimisation through, for example, the magistracy and use of juries. These mechanisms are grounded in the ‘twin principles of “local justice” and “justice by one's peers”’.Footnote 1 The community participation which these principles underpin is also present in mental health law. Section 23 of the 1983 Act contains a discretionary power of discharge, which authorises a panel to override the decision of a patient's Responsible Clinician to keep a patient on a compulsory care order – colloquially, a ‘section’ – discharging them against medical advice. It is a quasi-judicial process which provides community oversight of professional decision-making and patient rights. This power can be exercised either by those managing a mental healthcare organisation (Hospital Managers), or, more commonly, their delegates (Associate Hospital Managers, AHMs). AHMs are members of the community appointed by the healthcare organisation.

In 2004 the Government estimated that approximately 10,000 section 23 hearings took place in the preceding year, a similar figure to the number of Mental Health Review Tribunal hearings over the same period.Footnote 2 Notwithstanding the nature of the power, and scale of the process, little data about it is available. Despite this, since the mid-1990s there have been repeated calls to abolish section 23.Footnote 3 Such proposals overlook the fact that the twin principles are foundational to section 23 and contribute to the legitimacy of the whole Act. They provide an important counterbalance (but also a reflexive support) to professional power through community participation. This paper addresses the principled foundations of section 23, and its wider value to the legitimacy of the 1983 Act by developing an historical account of the connection between section 23 and the twin principles.

To demonstrate the importance of the local and latterly democratic credentials of section 23 to the mental health legal framework, I first introduce the discharge power as it exists today. I then explore the modern understanding of local, democratic justice generally, and in relation to the discharge power. Following this, the nineteenth century origins of the power, and its use by the local magistracy, are considered. This demonstrates, notwithstanding the oligarchic shortcomings of the magistracy in this period, the local nature of their power – the first of the twin principles mentioned above. Building on this, the process by which the Justices’ role in administering asylums, including the regulation of discharge, was transferred to democratically elected county councils under the Local Government Act 1888,Footnote 4 and the Lunacy Act 1890,Footnote 5 is examined. This process of democratisation aligned the discharge power with the second of the twin principles, democratic justice. The closing part of the paper reflects on how these principles were refined and consolidated throughout the twentieth century, resisting attack from the mid-1990s onwards, yielding a system of justice delivered by one's peers.

1. Section 23: the power of discharge

Section 23 allows for the review of many of the main compulsory care orders.Footnote 6 Reviews may be conducted in two ways: first, an oral hearing, supported by written evidence, attended by the patient, their relatives, legal representatives, and care professionals; secondly, a paper-based process.Footnote 7 The panels ordinarily sit in benches of three, must make decisions by a majority of three or more,Footnote 8 and give reasons.Footnote 9 There are four triggers for considering a case. First, any person subject to a relevant order may appeal at any time. Secondly, when an order is renewed, regardless of whether the patient challenges this. Thirdly, where the Responsible Clinician issues a barring order preventing the Nearest Relative from using their discharge power. Finally, AHMs may instigate a review on their own initiative.Footnote 10

NHS and independent healthcare organisations are responsible for appointing AHM panel members from the local community,Footnote 11 but, save for this, AHMs should be independent.Footnote 12 Delegating the power in this way better aligns with the principle of democratic justice than would be the case were the organisation itself to conduct the process. This is because, while NHS organisations are responsible for care in a geographically defined area, their authority is principally administrative in nature, and is exercised impersonally by their employees and directors. There is nothing about the character of one organisation's authority which differentiates it from another. Any geographic link that NHS organisations may have with a local area is coincidental, and absent for independent hospital organisations. Conversely, those appointed to sit as AHMs are of their local community.

Geography is important in other ways, however. The complexity of understanding this mechanism multiplies when one considers the fact that, because each healthcare organisation administers the AHM process locally, there is significant opportunity for variation.Footnote 13 With this in mind, while the legitimacy-producing capacity of the section 23 power rests on its local nature, we should be concerned about what has elsewhere been called ‘justice by geography’.Footnote 14 The principle of locality cannot ignore the rule of law requirement that like cases be treated alike. Lessons should be learned from work elsewhere, such as within the magistracy, to enhance the consistency of decision-making.Footnote 15 This warrants further exploration, but for now it is sufficient to say that, while the rule of law credentials of section 23 processes could be enhanced, this does not undermine the relevance of other principles to section 23, and the Act as a whole. In the next section I propose to explore the ideas of democratic, local justice, and the function of section 23 further.

2. Legitimacy and democratic local justice

Discussion of democratic local justice usually concerns two issues relating to the magistracy. First, magistrates’ anxieties about the loss of local democratic justice due to court closures, and the centralisation of court facilities, which negatively impacts their ability to situate a case in its local context.Footnote 16 Secondly, and alongside the above, ‘the link …’ which magistrates and court users make ‘… between the community and the [magisterial] judiciary’.Footnote 17 In particular, that they see the ‘assessments of fairness and justice…’ made by the magistracy as being ‘… based on the normal standards of ordinary members of the public’ – the local community.Footnote 18 Particular advantages identified by the users of magistrates’ courts, such as magistrates’ ‘specific knowledge of the area’, and ‘[awareness] of local needs’,Footnote 19 are lost if the process of justice is always distant and professionalised, undermining how such processes are understood locally.

Even if we are not wholly convinced by praise of the magistracy,Footnote 20 as Padfield explains, there are ‘strong arguments’ in favour of local democratic justice in principle, and ‘no obvious reason’ for removing it.Footnote 21 This can be seen in Hallet LJ's account of the ideal of magisterial justice:

Ordinary citizens appointed from among the communities they serve … understand local conditions and pressures in a way that a professionally qualified judge sitting in judgment miles away from his or her own area may struggle to do. They bring to their role a wealth of experience and breadth of knowledge not only of their communities, but of the world outside the law. The abiding strength of the magistracy is that it is comprised of local citizens …. Its understanding of local communities is a basic principle in community justice …Footnote 22

There are clear parallels between the ideal community justice function of the modern magistracy and the AHMs. First, as regards the importance of the community connection:Footnote 23 in the same way that a magistrate is expected to be familiar with their local area,Footnote 24 so too should AHMs possess local knowledge (for example, of the different forms of mental health care provision available) and be able to leverage this ‘local community interest’.Footnote 25 The second parallel lies in the importance of citizen participation in justice processes. AHMs are, like magistrates, ‘empowered citizens’ capable of ensuring due process and the protection of the rights of fellow community members.Footnote 26 This has been conceptualised by one NHS employee as an important counterbalance to ‘the very considerable powers of professionals’,Footnote 27 a view reiterated by an experienced AHM, who also drew a direct link between the AHMs, and the more familiar manifestation of the twin principles in the criminal justice system.Footnote 28

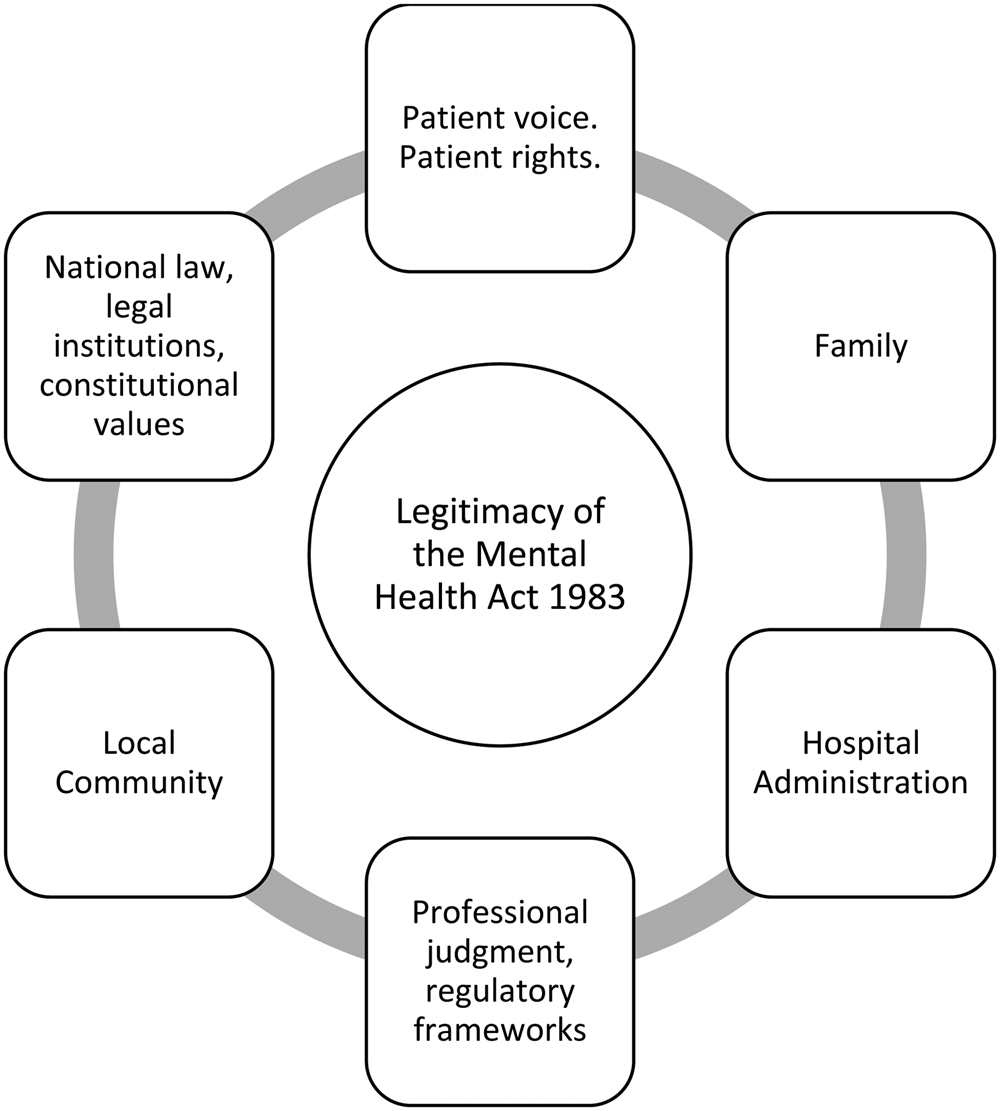

The characterisation of the AHMs as drawing their legitimacy from their local, community-based character is further reinforced when one considers how that legitimacy complements and counterbalances other sources of power, including other powers of discharge, in the Act. If we look specifically at discharge, we see that the Act creates a variety of powers to discharge people from compulsory care. These powers are variously entrusted to nationally administered institutions (the Mental Health Tribunal), healthcare professionals (the Responsible Clinician), family members (the Nearest Relative), local administrative units (eg NHS Trusts), and to members of the local community (AHMs). The legitimacy of these powers is derived from different spheres: the national system of justice and judicial appointments, professional regulatory frameworks, familial ties, legislation and government, the concept of local democratic justice, and the ability of the patient to demand those sources of legitimacy satisfy themselves that compulsory care is appropriate. Seen in this way, the discharge power entrusted to the AHMs, as representatives of the local community, is a key source of legitimacy to the mental health law framework in general (see Figure 1).Footnote 29

Figure 1. The sources of legitimacy of the Mental Health Act 1983

It is in the nature of involuntary mental healthcare that a patient cannot insist upon discharge, but the Act provides, as discussed, multiple avenues to challenge compulsory care, and to make representations to the other sources of legitimacy if these are rejected. These spheres of legitimacy both complement and counterbalance one another. For example, where an order is renewed under sections 20 or 20A, if review by the AHMs approves that decision, it supports the professional regulatory legitimacy of the Responsible Clinician, and the authority of the healthcare organisation by reassuring it that its employees are acting appropriately. In the second case, they provide an essential counterbalance to other spheres of power and legitimacy. For example, the Responsible Clinician, the Tribunal and the AHMs can, in almost all circumstances,Footnote 30 act unilaterally to discharge a patient from compulsory care. The nature of the discharge power entrusted to each sphere thus creates a high threshold for continued compulsory care, because those with a discharge power can act independently.Footnote 31

These observations demonstrate the principled foundations of a community-based source of legitimacy, and its value to the mental health law framework. There is, of course, room to improve, most importantly as regards the diversity of panel members. The Code primarily provides guidance on procedure, rather than the wider regulation of section 23. While we may expect that healthcare organisations will work to ensure the panellists they appoint are representative of their community, the Code could be more robust.Footnote 32 There is some evidence from 2004 that organisations have taken steps to enhance panel diversity.Footnote 33 However, concerns remain, as shown by the Report of the Independent Review, which notes that some healthcare organisations continue to ‘face challenges in recruiting AHMs that have experience of the ethnicity, culture, age and gender of the patients they are dealing with’.Footnote 34 Given the well-documented ‘excessively poorer experiences and outcomes of individuals from black African and Caribbean communities’ under the Act,Footnote 35 a process purporting to ground its legitimacy in its community connection must work to ensure that connection is real if it is to have the trust of the community.

In its ideal form, the AHM process represents the community in the review of powers exercised under the 1983 Act. It is a manifestation of local, democratic justice. Moreover, properly realised, it contributes to the legitimisation of the wider framework of powers under the Act by counterbalancing and reflexively reinforcing the national, professional, and administrative spheres. The roots of this legitimisation lead deep into the history of mental health law. The next section explores this history in relation to the first of the twin principles: local justice.

3. Local justice: the Quarter Sessions and the magistracy

The origins of the discharge power lie in the County Asylums Act 1808. The Act authorised the construction of the first public asylums, designating how, and by whom, they were to be managed.Footnote 36 Section 23 of the 1808 Act provided for the power of discharge to be exercised by those Justices of the Peace of the county quarter sessions who were members of the county asylum visiting committees (the visiting Justices) responsible for running public asylums. Section 23 reads:

XXIII And be it further enacted, That all Lunatics, insane Persons, or dangerous Idiots so committed to such Asylum, shall be safely kept, and that no such Person shall be suffered to quit the said Asylum or to be at large until the Visiting Justices or the greater Part of them, shall order the Discharge of such Person, and shall signify the same in Writing under their Hands and Seals…Footnote 37

This section explores the history of the magistracy and quarter session local government from 1808 onwards. Consideration of the character of the magistracy in the nineteenth century, and their involvement with asylum administration over the period, demonstrates the essential fact of their locality.

(a) The quarter sessions

In the nineteenth century, the county constituted ‘a single undivided unit of government’.Footnote 38 It was administered by the county quarter sessions, the principal unit of local judicial-administrative authority in England, described as a ‘county parliament’,Footnote 39 and a ‘rural House of Lords’.Footnote 40 The magistracy have a long association with local administration, originally from a concern to maintain order.Footnote 41 Early on, this was secured by exercising judicial authority, but from the sixteenth centuryFootnote 42 also involved the exercise of administrative power.Footnote 43 During the eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries, the majority of the substantial growth in local government administration fell upon the magistracy.Footnote 44 From the mid-eighteenth century onwards the quarter sessions had, in the absence of any other available local organisation of equivalent administrative capacity,Footnote 45 and with the trust of the central governing institutions,Footnote 46 accrued a host of powers.Footnote 47 Within these structures, what we would today consider the separate functions of administering the law, and its interpretation and adjudication, were combined.Footnote 48

This overview gives some insight into why the quarter sessions, via visiting committees, were entrusted with running asylums. Alongside this we should also remember the longstanding involvement of the magistracy in local control of the mentally unwell. As Gostin notes, under the Elizabethan Poor Law, magistrates sent the mentally ill to workhouses,Footnote 49 and under the Vagrancy Acts of the eighteenth century, Justices of the Peace could authorise their detention.Footnote 50 Given their activity in so many other areas of local administration, and their existing role in relation to mental illness in their localities, when legislation for the purpose of constructing asylums was contemplated, it was natural that the quarter sessions were given the necessary powers.

The legislative allocation of power also (partially) followed the sources of funding for the construction of asylums: the county rates. For much of the nineteenth century landowners were one of the main funding sources for the rates.Footnote 51 Given the property requirements for becoming a magistrate,Footnote 52 this meant that the Justices, as members of the landowning class, were notable contributors to the rates. Additionally, the Poor Law funds, which paid for the daily care of those held in asylums, were likewise levied on ratepayers.Footnote 53 Many magistrates were also ex officio members of the local boards of Poor Law Guardians that superintended these funds.Footnote 54

As I have intimated, not all ratepayers could access the power to expend public funds.Footnote 55 For example, yeoman farmers paid rates on land they owned, and could be elected as Poor Law Guardians.Footnote 56 Yet, while some farmers might own a sufficient quantity of land to qualify to sit as magistrates, their social class meant that they would not be admitted to the bench.Footnote 57 Nonetheless, these individuals contributed towards the cost of asylums.Footnote 58 This tension, which I return to below, only began to resolve at the end of the nineteenth century with the passage of the Local Government Act 1888.

(b) The magistracy

The preceding discussion tells us something of why the quarter sessions took responsibility for asylum administration. Yet, it is also necessary to understand who the magistracy were, since this provides an explanation as to why the continued expansion of their bureaucratic responsibilities, which included administration of county asylums, came to be seen as a democratically unsatisfactory, administratively inefficient means of conducting local government.

The democratic deficit of the magistracy lay in the oligarchic basis of their power, including several barriers to appointment to the bench.Footnote 59 First, the property qualification excluded all but the landowning classes.Footnote 60 Secondly, a prospective magistrate also had to be recommended by the Lord Lieutenant of the county,Footnote 61 and be politically acceptable to the local Bench.Footnote 62 Intellectual ability and administrative competence were not primary considerations.Footnote 63 The requirements of political patronage,Footnote 64 and long-established family ties and traditions of involvement with the county benches were more decisive.Footnote 65 The only exceptions to this were, at the start of the nineteenth century, clergymenFootnote 66 – who were often relations of the gentryFootnote 67 – and, later, industrial magnates.Footnote 68 The composition of individual benches varied,Footnote 69 some admitting industrialists, others not.Footnote 70 Thirdly, aside from the sources of their wealth and social status, to make use of the powers of their office, justices had to swear an oath, the dedimus potestatem. Eastwood suggests that only one third of all magistrates were sworn in the early 1800s, and amongst that number ‘a far smaller proportion can properly be described as genuinely active’.Footnote 71 This observation hints at a concern which developed over the course of the century regarding the administrative inefficiency of oligarchic local government.

More immediately though, this underactivity had implications for asylum administration, including for the power of discharge. As discussed earlier, section 23 of the 1808 Act made clear that the only way for a patient to be legally outside of the asylum was for the Justices to discharge them. Consequently, where visiting Justices disengaged from their obligations, this posed challenges to the practical legalities of running the asylum.Footnote 72 Despite the relatively small number of asylums constructed at the time, Parliament recognised the problem of magisterial absenteeism.Footnote 73 Jones argues that these provisions were necessary to combat ‘the apathy of the visiting Justices and the difficulty of inducing a quorum to be present…’.Footnote 74 Unsurprisingly, there are also various examples of poor management.Footnote 75

Since the history of the discharge power is bound up with that of the magistracy in general, clearly it cannot be romanticised. Nevertheless, the magistracy of the nineteenth century were closely associated with their locality, the county, and in the context of the wider development of the discharge power, that is significant. Though it sat within an oligarchic form of government, the system for authorising discharges established under the 1808 Act, and developed over the course of the century, met the requirements of the first limb of local, democratic community justice: locality.

(c) Deference, paternalism, professionalism

To understand how the second limb, democratic justice, came to be embedded in the law regulating mental health, and in particular discharge by local community representatives, three matters must be considered. First, the attitude of the magistracy and ruling classes generally. Secondly, how the arrangements underpinning their control of local government became ever more problematic, both democratically, and in terms of administrative efficiency, during the nineteenth century. Finally, the relationship between the magistracy and the psychiatric profession.

The first two issues can be considered jointly through the notion of deference. Together, the aristocracy, gentry, industrial magnates, and the clergy-magistrates, occupied a position close to the apex of a society founded upon deference to one's social superiors.Footnote 76 While this system lasted,Footnote 77 alongside the pragmatism of securing access to power, social prestige, and the historical entrenchment of family participation in local government,Footnote 78 one thing consistently motivated the landed classes to undertake public service: paternalism.Footnote 79 Paternalism did not have a uniform meaning to those exercising public power, but one common feature was that, while it entailed some logic of care on the part of the upper classes, it would not countenance deviation from the established social hierarchy.Footnote 80

Commentators have taken varied positions on the merits of this outlook, and how it impacted quarter session administration. For some, the administrative burden associated with the Justices’ work suggests that a real commitment to public service was required.Footnote 81 Indeed, there are examples of engaged, effective magisterial management of asylums, for example.Footnote 82 However, in general, the nineteenth century magistracy have not attracted praise. Even at the more charitable end of the spectrum, the picture is unedifying. Roberts describes the justices as working ‘with … good intent but limited vision’, as ‘possessed [of] … patriarchal kindness’, while being ‘amateurs at government’.Footnote 83 Less sympathetic positions describe the justices as ‘short-sighted and fumbling’,Footnote 84 and as lacking ‘a sympathetic and conscientious attitude to their administrative responsibilities’.Footnote 85 EP Thompson's withering assessment of paternalism as unjustifiably legitimising power underpinned by wealth, is apt.Footnote 86

The social structures which underpinned paternalism and deference were duplicated in the relationship between the lay magistracy and professional asylum medical superintendents. The Justices remained in a superior position to medical superintendents, both legally and socially, until the end of the century; the latter ‘remained answerable’ to,Footnote 87 and were ‘notably powerless’ before the Justices.Footnote 88 This does not mean that the Justices took it upon themselves to select patients for discharge. As they did in respect of professional opinion received in other areas,Footnote 89 the Justices took advice from the medical superintendent, and, if they agreed, acted accordingly.Footnote 90 However, though the magistracy had respect for medical opinion, and while they might pay attention to medical recommendations, they were ‘not averse to treading on … superintendents’ toes in autocratic supervision of established asylums’.Footnote 91

The subjugation of local superintendents stands in contrast to the developing national position of the psychiatric profession. Fennell argues that, as early as the 1840s, psychiatry had consolidated its position as the profession competent to assess mental disorder,Footnote 92 though Turner is more sceptical of the wider impact of the Medico-Psychological Association, the nascent professional association for psychiatry, as a coherent force capable of advancing the profession in public life.Footnote 93 In terms of securing control of the regulatory framework, though, professionals did enjoy some success over their lay counterparts, as can be seen by briefly considering developments in this area. In 1828, the medical professionals involved in the work of the then central regulator, the Metropolitan Commissioners in Lunacy, held five of the fifteen positions on the Commission as of right,Footnote 94 five of the others were magistrates.Footnote 95 Subsequently, in 1845, legislation provided that there should be five lay Commissioners alongside three barristers, and three medical Commissioners, with the Chair required to be a lay person.Footnote 96 Echoing modern concerns about the AHMs, the medical Commissioners of 1845 ‘felt that … [lay] intervention infringed professional practice’.Footnote 97

Psychiatrists suffered a professional setback in the face of the legalism of the Lunacy Act 1890,Footnote 98 but around this time there was a shift in the composition of the regulator that diminished lay involvement.Footnote 99 Indeed, in contrast to earlier incarnations of the central regulator, the Lunacy Commission were ‘highly sensitive to the need not to interfere in matters of [local] clinical judgment’.Footnote 100 Thus, although local tension between the lay magistracy and the medical profession was limited by extant social and legal power structures, by comparison, at the centre, professionals were in the stronger position. That the landed classes were able to preserve oligarchic power locally, despite the growing influence of the psychiatric profession centrally, speaks to the control which they exercised both within their locality, and through positions they controlled in Parliament.Footnote 101 Indeed, as well as stemming the tide of professional power in mental health, it also had the much wider effect of enabling them to preserve their powers despite the national advance of democracy. The dissonance this produced became increasingly ‘both anomalous and indefensible’.Footnote 102

4. Democratic justice: the Local Government Act 1888

While the constraints placed on psychiatrists by Parliament in their capacity as medical superintendents were unremarkable in a system of deference,Footnote 103 this did not resolve the tension between the nascent psychiatric profession and the magistracy. One can appreciate the difficulty: the magistracy, notwithstanding their local ties, enjoyed their position because of their social class. Their involvement in asylum administration made little sense given the presence of a profession whose developing skills and expertise justified their taking a leading role. Plainly, the system of deference and paternalism which enabled the propertied classes to maintain such a counter-intuitive arrangement was unsatisfactory.

When reform of magisterial local government arrived via the Local Government Act 1888, it was driven by national trends and affected all local governmental activity. Crucially, for our purposes, the 1888 Act, in conjunction with the Lunacy Act 1890, converted the source of the discharge power from one predicated upon an increasingly illegitimate oligarchic foundation, to a democratic one.Footnote 104 The consequences of this may have been appreciated at the time, but discussions seem to have been quite limited.Footnote 105 The reforms created an unanswerable justification for the presence of lay people in the mental health law framework, and particularly in the oversight of powers exercised under it. Not only was the power local, it was also now democratic. While psychiatrists might reasonably have contested the involvement of an oligarchic body, their position against a democratically endorsed officeholder, howsoever embryonic the democratic system which put them there, was substantially weaker.

This reconfiguration merits further consideration. The impetus behind, and the impact of the 1888 Act on the discharge power were the product of external forces. The important technical developments in the locus of the discharge power, moving from the quarter sessions to the new county councils,Footnote 106 occurred for reasons not directly connected with asylums. As such, to understand the profound, principled consequences of the 1888 and 1890 Acts for the discharge power, the wider social context which precipitated the shift from oligarchic to democratic government must be examined. There were two forces at work. First, the growing traction of the principle of democracy itself. Secondly, the practical demands arising from the development of democracy and the concomitant need for efficiencies in central legislative and governmental practice.

Against this backdrop, oligarchic quarter session local government looked increasingly outmoded.Footnote 107 The opposition to local democracy in principle was especially problematic.Footnote 108 This attitude stood in contrast to the national direction of travel, which, through the Reform Acts, removed rotten boroughs, and expanded the electoral franchise. To this we may add, first, the passage of the Secret Ballot Act in 1872;Footnote 109 secondly, the erosion of the gentry's local political power;Footnote 110 thirdly, growing divergence between the beliefs of the landed and the ordinary working classes;Footnote 111 fourthly, changes in the relationship between the working classes and landed estates, and the expansion of central government;Footnote 112 and, finally, the corresponding rise in agitation for democratic representation.Footnote 113 All of this impacted the outcome of national elections, contributing towards a reduction in the strength of the landed interest in the House of Commons.Footnote 114

Practical concerns with the quality of governmental administration, linked to the expansion of the state to satisfy the desires of a growing electorate, overrode objections to centrally-driven standardisation of local government. The growing complexity of the state placed increasing demands on central governmental and parliamentary time.Footnote 115 Historically, local government had been founded on powers derived from local Acts made at Westminster on the petition of individual localities.Footnote 116 This generated a significant amount of work for Parliament, which only grew as the state's local activities expanded.Footnote 117 Yet, in the absence of a democratically authorised, bureaucratically competent local body to carry out this work, it fell to Parliament.

This expansion of the state also had a second democratically-connected practical financial effect: an increase in the costs of the county rates.Footnote 118 According to Davis, for much of the nineteenth century comparatively little local governmental activity was centrally funded, and was instead paid for by county ratepayers. Historically, central and local government negotiated with one another regarding taxation, and within this the magistracy could leverage the extensive landowning interest in Parliament to their advantage.Footnote 119 However, this position was not sustainable. There was a concern in central government about how giving the oligarchic quarter sessions control over an increasingly large pot of publicly-derived funding looked.Footnote 120

Taken alongside democratisation at the national level, this increase in costs raised the related questions of: (i) who should pay? and (ii), if the sources of local taxation expanded through growth in the franchise, how would the views of these new ratepayers be taken into account? While the yeoman farmers may have occasionally posed problems as a nominal force without representation, an expanded franchise would create a much larger cohort of unrepresented ratepayers. Nonetheless, the landed interest resisted proposals to introduce elected councils.Footnote 121 Given this difficult socio-political context, it is unsurprising that the government opted for pragmatism,Footnote 122 producing an Act consisting of ‘concessions and compromises’.Footnote 123

The 1888 Act made its way through Parliament in a muted fashion, with neither the government nor opposition benches taking much interest.Footnote 124 The county councils it created were partly democratically elected, and partly appointed. The elected members, who formed the majority, selected the appointees (aldermen), who themselves constituted one third of the number of elected members.Footnote 125 The aldermen appointed following the first elections in 1889 were almost all magistrates who had previously been members of the quarter sessions, or, as the then Attorney General put it, ‘men of more experience and ability than popularity’.Footnote 126 However, many magistrates also enjoyed success, often unopposed, in the first local elections.Footnote 127 The picture in relation to county council visiting committees, which had inherited the discharge power, was similarly mixed, varying according to local context.Footnote 128

Few contemporary sources comment on the impact of this shift on the discharge power. However, Redlich and Hirst, writing in 1903, framed the power to admit and release people from asylums as ‘purely judicial’,Footnote 129 as separate from the ‘administrative duty [of inspection] … conferred on the … County Council’.Footnote 130 This distinction requires unpicking. The power to admit patients stayed with the magistracy, but all other powers, including the power to discharge, passed from them to the county council visiting committees. Thus, while exercising otherwise purely administrative functions, the county council visiting committees could authorise a discharge from the asylum as an aspect of their powers of review and visitation.Footnote 131 In the late-nineteenth century the distinction between administrative and judicial power was hazy,Footnote 132 but Butler's later observation that ‘pauper patients [seeking discharge] had to appeal to the asylum visiting committee’ suggests that the process was not what we would today recognise as a purely administrative exercise.Footnote 133

Behind the relocation of the discharge power was a more important, principled shift. Notwithstanding the continued success of the landed classes in some democratic elections, there had been an incontrovertible shift in the basis of local governmental power. Whatever the motivations of an electorate which continued to vote for the gentry, it was a choice made at the ballot box. For asylums, the basis of the power to discharge people from compulsory care in hospital likewise shifted. The 1888 Act transformed the power of discharge, moving it from an oligarchic to a democratic basis, to be exercised by those elected or appointed by the community. In this way, what started the century as a local power now also possessed democratic credentials. Subsequent expansion of the electoral franchise in the first half of the twentieth century only served to cement this, and further debilitate the coherence of professional opposition to lay community oversight.

5. Local democratic justice in the twentieth century

Over the course of the nineteenth century, and as a result of the 1888 and 1890 Acts in particular, into the twentieth century, local, democratic community decision-making processes became a firmly established component in the oversight of compulsory mental health care. None of the legislative changes which followed over the course of the twentieth century diminished this. In what follows, I develop previous discussion of the history of section 23, which concerned the debate over abolishing the power,Footnote 134 by connecting it to the principled developments originating in the nineteenth century that have been the subject of this paper. This approach has two advantages. First, it provides an account of the major legislative developments in the history of section 23 in one place. Secondly, and more importantly, it shows that the principles of local, democratic justice established in the nineteenth century remained relevant throughout the twentieth century, and to the present day. The twentieth and early-twenty-first centuries saw a progressive separation of administrative-managerial members (today, Hospital Managers) from those individuals specifically appointed from the community to exercise the discharge power (today, AHMs). Consequently, one might reasonably say that the principles were consolidated, even enhanced, by developments in this period.

The Act which began this movement was the Mental Treatment Act 1930. This Act allowed local authorities to appoint non-council members – community appointees – to sit on visiting committees.Footnote 135 The Macmillan Commission, which informed the 1930 Act, suggested that these reforms would benefit the work of the committees by allowing ‘persons with perhaps greater leisure, local knowledge and special aptitude for this work’ to undertake visiting functions,Footnote 136 a view endorsed by government.Footnote 137 Neither the Commission nor Government dwelt on the implications of this change,Footnote 138 perhaps because evidence submitted to the Commission suggested that the visiting committees’ power of discharge did not ‘… appear to be very frequently exercised’.Footnote 139 The changes similarly received little attention in Parliament. The minister in charge of the Bill, Earl Russell, who had been a member of the Commission,Footnote 140 felt that the measures were so inconsequential that he ‘need not say much about’ them;Footnote 141 a view which Parliament appears to have agreed with.Footnote 142

As such, when the Act passed, it made no changes to the discharge power,Footnote 143 save that the accompanying statutory rules replicated the process for the new category of ‘temporary patients’.Footnote 144 Geere's recollection of the workings of visiting committees after the passage of the 1930 Act, including fortnightly consideration of requests for discharge, are likewise not suggestive of any radical departure from previous practice.Footnote 145 Thus, the significance of the 1930 Act for the discharge power stems primarily from the possibility of community appointees exercising the power, rather than any radical structural change.

This visiting committee structure persisted until the passage of the NHS Act 1946, which established the National Health Service, and transferred the powers of the county council visiting committees to the newly-created Hospital Management Committees (HMCs).Footnote 146 HMCs, through the Regional Hospital Boards which oversaw them, were granted wide powers of appointment covering a range of constituencies, including local authorities.Footnote 147 Grounding day-to-day hospital administration locally in this way reflected wider political concerns about centralising power over healthcare, which made local, democratic oversight as a counterbalance to centralisation key.Footnote 148

The local, community-orientated qualities of the HMCs remained important in the overall framework in the decade following the 1946 Act. Millward's experience of working with HMCs in this period reflects this. He notes that HMCs were intended to ‘represent a cross-section of the community’,Footnote 149 connecting the hospital with its users and wider population.Footnote 150 This connection is also seen in evidence given to the Percy Commission, the Report of which informed the passage of the Mental Health Act 1959.Footnote 151 The Royal Medico-Psychological Association (later, the Royal College of Psychiatrists), for example, were supportive of the HMC power of discharge in their evidence, seeing it as an ‘established safeguard’ against improper detention,Footnote 152 and viewing the HMCs as the successors to the visiting justices.Footnote 153 The Commission's views were more mixed,Footnote 154 though they too noted a link between the HMCs and magistracy,Footnote 155 and thought it important to retain their local powers, notwithstanding proposals to create a Mental Health Review Tribunal.Footnote 156 This shows that, despite reforms to the legislative structure governing compulsory mental health care, maintaining a productive tension between the local and central, democratic and professional characteristics of the various safeguards was considered important.

At the same time, in the course of parliamentary debate preceding the 1959 Act, it was suggested that civilian oversight of medical opinion was not as robust as could be hoped.Footnote 157 However, as was the case with the 1930 Act, when opportunities to debate the discharge power arose, the relevant clause was passed without comment.Footnote 158 Whether there was anything in this criticism, the apparent lack of interest in addressing it must be seen in its wider context. First, the principled concerns about local/central and democratic/professional power were certainly present, and might on their own have stayed Parliament's hand. More generally, there was concern amongst some parliamentarians about the removal of magisterial involvement from the admissions process, one of the most significant changes of the 1959 Act,Footnote 159 and a more general scepticism about trusting entirely to the views of professionals.Footnote 160 These more immediate concerns may have taken precedence over scruples about the zeal of the HMCs in relation to discharge. In the end, while the magistracy lost their role in admitting patients, the 1959 Act retained both the role of the HMCs in discharging patients,Footnote 161 and the ability to appoint people for that purpose.Footnote 162

The extent to which this appointment power was used in practice is less clear. As was explained by Bevan, who was responsible for guiding the NHS Act 1946 onto the statute book, the structure of the NHS was designed around a chain of accountability connecting local (Hospital Management Committees), regional (Regional Hospital Boards), and national (Ministry of Health) authorities. Additional individuals could be appointed to sub-committees for specific purposes, but the tone of Bevan's remarks do not suggest great enthusiasm for this.Footnote 163 This attitude appears to have been reflected in the Ministry's Memorandum on the 1959 Act, which suggests that HMCs ‘will probably wish to authorise all, or a large number, of their members’ to exercise the power,Footnote 164 making no reference to specially appointed sub-committee members.

Even if there was an absence of external appointees, Millward's observations about the composition of the HMCs show that this would not have cut the thread of local, democratic community justice running through the history of mental health legislation, nor the discharge power specifically.Footnote 165 HMC members were drawn from the community and played an active role in considering the use of the power of discharge. Though the practice of proactively interviewing patients for discharge was, according to some sources, diminishing in the years before 1959,Footnote 166 and was discouraged by the Ministry after the Act was passed,Footnote 167 there remained, at minimum, a paper review process.Footnote 168 Both the paper and the interview-based mechanisms constituted a safeguard against improper detention, administered by members of the local community.

HMCs were replaced with Area Health Authorities in 1974 as a consequence of the NHS Reorganisation Act 1973,Footnote 169 which were in turn replaced by District Health Authorities in 1982Footnote 170 (hereinafter both ‘Authorities’). For present purposes, the shift in the ethos governing appointments to these authorities is probably more important than any structural change to the wider NHS. Instead of the focus on local volunteers bringing a range of skills, the overriding consideration in appointments became ‘expertise in management’,Footnote 171 as shown by the Government's thinking at the time.Footnote 172 This change in focus does perhaps explain why, if the discharge power was predominantly exercised directly by HMC members before 1973, it has subsequently come to be exercised mainly by specially appointed AHMs today.Footnote 173 The growing complexity of NHS administration, which would absorb time, coupled with a more managerial focus for Board members, which would make it less appropriate for them to exercise a historically community-based safeguard, created an environment in which delegation of the discharge power became not merely more routine, but expected.Footnote 174

In 1974 the Department of Health and Social Security issued a circular indicating that, while the sub-committees of the new Authorities now responsible for considering exercise of the discharge power ‘may not consist wholly of non-members’, individual decisions about discharge could be made by ‘three members who are not members of the authority’, subject to a signature by the chair of the committee.Footnote 175 Similarly, the Government's 1978 Review of the Mental Health Act 1959, which preceded the passage of the 1983 Act, outlines, inter alia, an intention to issue guidance directing Authorities to establish a formal procedure,Footnote 176 and to set up sub-committees to exercise the discharge power.Footnote 177 It was hoped that this would ‘build up expertise and confidence’ and so ‘play a positive role’ in what it viewed as ‘an important safeguard for patients’.Footnote 178 Again, the government reiterated that those exercising this function would not themselves need to be Authority members; the power could instead be delegated to appointees.Footnote 179 Thus, although the administrative structures of the NHS had changed, the community link found in the lay membership of the HMCs had been preserved, at least for the purposes of exercising the discharge power, by a conscious effort to establish sub-committees consisting, in part, of people who were not Authority members.

The Secretary of State for Social Services’ general remarks to Parliament on the 1978 Review, particularly the observation that detaining someone in hospital was an ‘action of society’, may suggest that the government was aware of the relevance of community involvement,Footnote 180 and wished to preserve it. As with earlier enactments, the plausibility of this assessment of contemporary sentiment finds support through an examination of the legislative process; in this case, of the draft Mental Health (Amendment) Bill 1981–82.Footnote 181 First, the Bill did not seek to amend the discharge power, section 47 of the 1959 Act. The 1983 Act consolidated the 1959 Act and the Amendment Act 1982, with section 47 becoming section 23 in the 1983 Act.Footnote 182 No attention was paid to the discharge power by government,Footnote 183 nor Parliament,Footnote 184 with very little added by contemporary commentators, save that the discharge power should ‘be preserved’.Footnote 185 This suggests that the power was acceptable in its current form. Secondly, reflecting the 1978 Review, lay involvement elsewhere in the Act was positively endorsed, for example, in relation to the Mental Health Act Commission,Footnote 186 and to control professional decision-making.Footnote 187 Given the long-established trajectory of sentiment around local, democratic involvement in mental health legal processes, the passive approach to section 47/section 23 during the reform process, and the wider preferences for lay involvement, strongly suggest that the twin principles remained embedded in the mental health legal framework at the inception of the 1983 Act. However, the position was not settled. A rupture between those favouring concentrating the discharge power in the hands of managerial members, and those arguing for the continuation of community-centred oversight, was developing.Footnote 188

The rupture began with confusion in the late 1980s and early 1990s over whether externally appointed persons (ie AHMs) could exercise the discharge power alone without a managerial member present (ie a Hospital Manager); could only do so alongside Hospital Managers; or whether only the Hospital Managers could do so. The preceding discussion will have given the reader an indication of the likely resolution to this confusion, but for confirmation, four related disagreements, each pulling in different directions, and examination of how these were resolved, merit consideration. First, in 1985 and 1990, guidance was provided to healthcare organisations advising that external members could not be used,Footnote 189 but this was soon reversed.Footnote 190 Secondly, in 1990, a legislative error appeared to go against the recently reasserted normal practice of allowing externally appointed panellists, creating serious practical difficulties.Footnote 191 Thirdly, in 1994, the parliamentary debate on the amendments to correct this error endorsed the practice of utilising ‘experienced outside members’ to conduct hearings, describing this as the ‘widespread practice’, and the ‘intention of the legislation’.Footnote 192 In the same debate managerial members were described as having ‘no training and … little or no experience in this role’,Footnote 193 and as ‘not necessarily [having] the required expertise’ to carry out the function.Footnote 194 Finally, guidance in 1996 suggested there was perhaps ‘merit’ in a Hospital Manager chairing the panel, but acknowledged that this ‘[had not been] the usual practice’.Footnote 195 This final point appears to indicate that, despite the preceding confusion, over this period the trajectory remained towards the consolidation of the twin principles through the use of community appointees alone.

Still, the matter was not entirely settled, and there remained opposition to reliance on community appointees. For example, again in 1996, a Working Group appointed by the Minister for Health to consider section 23 recommended that guidance be issued that AHM panels should ‘ordinarily’ include a Hospital Manager,Footnote 196 indicating a reversion to the disagreements of 1985–1990.Footnote 197 When the next edition of the Code was published in 1999, it took a middle path inasmuch as it suggested that a Hospital Manager should chair a section 23 panel ‘if possible’,Footnote 198 leaving the disagreement unresolved. In the same year, the Richardson Committee reported on its proposals to reform the 1983 Act. Amongst these proposals was a recommendation to abolish the AHMs entirely. While the Committee acknowledged ‘that [AHMs] provide an important lay element and link with the local community’Footnote 199 they saw ‘no proper role’ for them.Footnote 200 The Committee suggested government merely ‘encourage the involvement of local communities’.Footnote 201

The abolition proposed by Richardson and others was never carried out. Until recently one could have concluded that the recommendations of the 1996 Working Group, the intimation of the guidance issued in the same year, the 1999 Code, and Richardson's abolition proposals were the high-water mark of formal attempts to circumscribe the longstanding, routine involvement of the community in mental healthcare oversight. Two developments in the mid-2000s lend weight to this conclusion. First, a further legislative error and correction in 2003 and 2006 respectively.Footnote 202 As with the error of 1990–1994, the correction of this issue left open the possibility of Hospital Manager involvement in theory.Footnote 203 However, the parliamentary debate preceding the amendment clearly indicated that normal practice was for AHMs to staff the majority of section 23 panels without Hospital Manager involvement,Footnote 204 a position confirmed in the explanatory notes to the Mental Health Bill 2006.Footnote 205 Secondly, when a new edition of the Code was issued in 2008, after the passage of the Mental Health Act 2007, the ‘if possible’ requirement of the 1999 Code had been further diluted.Footnote 206 These developments make clear that, as recently as 2006, when discussion about reform of the 1983 Act was proceeding in earnest, and in 2008 when the new Code was published, a local democratic oversight mechanism was sufficiently robust to survive repeated, significant challenges.

Nonetheless, recent developments suggest that the underlying disagreement about the role of the AHMs, and in particular the importance of having a local, democratic presence with the teeth to provide oversight, remains. Indeed, a very similar suggestion to Richardson's mere ‘community involvement’, that AHMs be relieved of their discharge power and become ‘Hospital Visitors’ without any formal powers, was made by the 2018 Independent Review.Footnote 207 The subsequent White Paper and Consultation went further, proposing abolition of the AHM process without even the suggestion of weak community oversight offered by the Independent Review.Footnote 208 The Government's Response to the Consultation retreated somewhat from this, noting that ‘the response to this question was far more mixed than … anticipated’,Footnote 209 but still concluded that increased pressures on clinical and administrative time arising from enhanced access to the Tribunal, might necessitate abolishing the AHMs.Footnote 210

The recently published Draft Mental Health Bill contains provisions that increase the frequency with which patients are automatically referred to the Tribunal.Footnote 211 The Bill also proposes shorter detention periods.Footnote 212 These provisions are likely to have two related effects. First, there will be an increased burden on clinical and administrative time. AHM hearings will contribute to this because shortening detention periods will result in more frequent automatic AHM renewal hearings.Footnote 213 Secondly, any AHM renewal hearings which coincide with an automatic Tribunal hearing will appear to duplicate one another.Footnote 214 Despite the predictability of these impacts, neither the Draft Bill nor the Explanatory Notes make any mention of the AHM discharge power.Footnote 215 This is disappointing not only because it continues the haphazard approach to the development of section 23,Footnote 216 but more importantly because it fails to make a principled case for local, democratic justice in the Act. It implicitly minimises the relevance of the community, and may be viewed as conflating the basis of its legitimacy with that of the Tribunal.

Conclusion

As has been shown, the twin principles of ‘local justice’ and ‘justice by one's peers’,Footnote 217 are of both historic and continuing significance not just to the section 23 discharge power, but are also, through this, embedded in the history and legitimacy of the mental health legal framework more generally. The creation of local magisterial oversight of asylums by the 1808 Act, the establishment of democratic control of mental health institutions by the 1888 and 1890 Acts, and the trend which these provisions started have, over the course of two centuries, secured substantive local, democratically mandated oversight of mental health legislation. These arrangements are not a vestige of nineteenth century local government. They have persisted because, far from being an aberration, change in this area has paralleled the development of the principles of democracy in general, and local, democratic justice in particular, elsewhere. This can be seen in the fact that, at each opportunity to reform the discharge power, the principles of locality and democracy have resonated. Moreover, such principles retained, even enhanced, their relevance as other aspects of local governmental and healthcare administration shifted in response to changing political winds.

Today, the practice of appointing AHMs directly from the community binds the discharge power to its local, democratic roots. As such, while pressure for greater control from the centre over administrative and funding structures may ebb and flow according to political whim, this does not impact the principles underpinning AHMs. This is because, while AHMs’ legal authority to discharge people against medical advice is conferred in statute, their legitimacy to do so is a product of their local, democratic qualities. That legitimacy can only be transferred to another source with equal or better local and democratic credentials. The Tribunal, for example, cannot possess it. The legitimacy of the Tribunal is separately derived. Like jurors and magistrates, the democratic credentials of AHMs lie not in their election, but in their nature as members of the local community of which they, and patients, are members, and the underlying value placed in justice delivered by one's peers.

That legislative processes continue to overlook the significance of these principles, and the role which section 23 plays in bringing them into the Act, is deeply problematic. The participation of a local, democratic community in the delivery of justice, especially where the liberty and other rights of a person are at stake, is irrefutable. The removal, by accident or design, of mechanisms which incorporate such principles into the mental health law framework would be contrary to the historical direction of travel, and established principled foundations of the law in this area, and as such would constitute a serious misstep in the development of mental health law. It would fundamentally diminish the legitimacy of any future system of compulsory mental health care.

Declaration of interest

The author sits as an Associate Hospital Manager for Lancashire and South Cumbria NHS Foundation Trust.