An inclination toward pro-social behavior is widely understood to be a human universal. In the phrase of Gerber and Green (Reference Gerber and Green2010, 331) this inclination entails ‘a basic human drive to win praise and avoid chastisement’. The result is ‘social influence’, as people are induced to act in the ways they observe others acting. Despite agreement among scholars about the deep roots of social influence in the human experience, relatively little research has been dedicated to assessing the extent to which it is broadly present in political behavior, especially across diverse countries and for diverse political acts (Siegel, Reference Siegel2011).

The large literature on social influence and politics is built mainly on experimental studies of single behaviors in one country. In some cases, these have been replicated in select other countries. For example, social influence in Get-Out-the-Vote (GOTV) campaign mobilization is very well-known in the USA context. In GOTV studies, researchers provide citizens with information about one another’s voting behavior, and measure the effect (e.g. Gerber and Green, Reference Gerber and Green2000). This approach to studying social influence has also been found in county- and district-level voting in China (Guan and Green, Reference Guan and Green2006) and in a UK general election (John and Brannan, Reference John and Brannan2008), but has not been shown broadly. Similarly, the ‘companion effect’, in which people living together in a household influence one another’s likelihood of voting, has been shown in Denmark and replicated in the UK (Bhatti et al., Reference Bhatti, Fieldhouse and Hansen2020) but has not been tested across diverse contexts. Perhaps the most broadly known social influence effects in political behavior involve participation in revolutionary protest. Social influence can contribute to the rapid spread of protest in many settings (Opp and Gern, Reference Opp and Gern1993; Doherty and Schraeder, Reference Doherty and Schraeder2014; Walgrave and Wouters, Reference Walgrave and Wouters2014). Studies such as these, showing select effects in various settings motivate our primary question in this study: How widespread across countries is social influence on political behavior?

There are reasons to expect that social influence is wide-ranging. People influence one another’s behavior in many ways. In some of these, influence should be independent of political and social norms, institutional arrangements and opportunities for acting, and other aspects of political context (Bond et al., Reference Bond, Fariss, Jones, Kramer, Marlow, Settle and Fowler2012; Doherty and Schraeder, Reference Doherty and Schraeder2014). A good example is social or behavioral ‘contagion’, which involves behavior spreading from one person to another through simple contact or observation, even in the absence of verbal cues. Social contagion has been shown in voting (e.g. Bond et al., Reference Bond, Fariss, Jones, Kramer, Marlow, Settle and Fowler2012) and in the literature on revolutionary protest (e.g. Doherty and Schraeder, Reference Doherty and Schraeder2014). It has also been reported across a variety of non-political behaviors, especially in health and consumer behaviors (Araujo et al., Reference Araujo, Neijens and Vliegenthart2017; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Fam, Goh and Dai2018). This provides a theoretical rationale for expecting at least some forms of social influence to work independently of context.

In addition to asking how broadly social influence occurs across diverse contexts and behaviors, we are interested in whether it is moderated in universal ways. Social influence can, in principle, be moderated by factors at the individual level and group levels, such as personality and strength of ties (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Renström and Sivén2021; Doherty and Schraeder, Reference Doherty and Schraeder2014). For instance, social influence is sometimes greater in strong-tie networks (e.g. Bond et al., Reference Bond, Fariss, Jones, Kramer, Marlow, Settle and Fowler2012), but in some cases signals about the actions of large numbers of people in weak-tie networks exert more influence on behavior (Doherty and Schraeder, Reference Doherty and Schraeder2014). The most theoretically promising candidate for a universal moderator of social influence is age, which we explore in the present study. In order to expand upon our primary question about the universality of social influence, we also ask about the extent to which age may moderate social influence across contexts and behaviors.

To answer our questions in this study, we depart from the experimental tradition, exploiting a large and unusual data set: a 19-country, two-wave panel survey in the Americas, Europe, Eurasia, and the Asia-Pacific region. Survey research is less common than experimental studies of social influence but has been employed successfully to understand the spread of behavior among people (Doherty and Schraeder, Reference Doherty and Schraeder2014). Below, we detail our efforts to overcome the hazards of a survey design, including the need to measure a proxy and the need to overcome endogeneity. Our results suggest that a robust relationship exists between perceptions that others are acting politically and three categories of behavior across diverse national contexts: political expression, political consumerism, and public engagement. This relationship exists across diverse countries but is not present for every behavior in every country. This leads us to the conclusion that social influence on political behavior has a high degree of context-independence, despite falling somewhat short of being thoroughly universal. We find a positive moderating effect of age. While strong efforts at identifying causal mechanisms ultimately must rely on experiments, we interpret our survey findings to mean that political behavior researchers may benefit from accounting for social influence effects in addition to traditional predictors of behavior.

Social influence

Comparative analysis of political behavior rightly emphasizes how variation in national context is important to understanding variation in individual-level behavior across countries. For the most part, relationships between predictors and political behaviors are not universal but vary among countries with dissimilar institutions, parties, electoral rules, and cultures. A predictor of behavior could be defined as universal to the extent that it meets two criteria: exerting consistent effects across diverse national contexts, and across diverse behaviors. The most well-studied category of predictors with a high degree of universality is political and civic resources at the individual level. Time, skills, income and related resources are frequently predictive of behavior, although these vary with the behavior in question and with context (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Brady and Schlozman1995; López and Dubrow, Reference López and Dubrow2020).

Social influence is a domain of theory with some promise of universality. Social influence works though many mechanisms or pathways, and these are often entangled with one another. It is important to differentiate between pathways that are highly contingent on context and action from those that are not. Among the contingent pathways are those that work via shared social or political norms relevant to a particular behavior. For example, observing people voting may prime others to think about their sense of civic duty to cast a ballot and their desire to act in ways that garner social approval (Gerber and Green, Reference Gerber and Green2000; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Green and Larimer2008; Nickerson, Reference Nickerson2008). This pathway does not necessarily generalize to other behaviors where civic norms differ, or to societies with weaker norms around voting. In a society where protesting, boycotting, or striking are considered part of the socially approved repertoire of politics, such actions are likely to be mutually influential. The opposite is likely in a society where such actions are stigmatized. Social influence pathways should not be universal where behavior-specific and society-specific norms condition people’s influence on one another (Dalton, Reference Dalton2007, Reference Dalton2008; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Oser and Marien2016).

Another contingent set of pathways involve the information effects of social signals (Huckfeldt and Sprague, Reference Huckfeldt and Sprague1995; Houck et al., Reference Houck, Taylor and King2021). Communication among family members, friends, neighbors and even strangers can convey information that affects people’s assessment of whether to act. For example, when neighbors turn out for a protest, they reveal their preferences publicly, in a high-cost way. If those preferences were previously concealed or uncertain among neighbors, as might be the case in a repressive regime, these social signals can affect behavior in large and sometimes unforeseen ways (Doherty and Schrader, Reference Doherty and Schraeder2014).

In contrast to these social influence pathways that are contingent on context and type of action, other pathways are independent. These provide the basis for an expectation that social influence may be widely present across nations and behavior. Studies of conformity show that people exhibit a tendency to act and think with one another in a surprising variety of ways and contexts. The classic studies of Asch in the 1950s showed that subjects shown a set of lines of varying size and given a trivially easy task of comparing lengths will report mistaken judgments if others do so first (Asch, Reference Asch1956). This effect is not contingent on national context, although some variation can occur across culture (Bond and Smith, Reference Bond and Smith1996; Cialdini et al., Reference Cialdini, Wosinska, Barrett, Butner and Górnik-Durose1999; Kim and Markus, Reference Kim and Markus1999). This kind of social conformity occurs in many domains of behavior.

Social contagion research provides many examples of mutual influence. An enormous diversity of behaviors can spread among people in networks of all kinds, affecting product and brand adoption, health and sexual behaviors, voting, and participation in protest (Burnkrant and Cousineau, Reference Burnkrant and Cousineau1975; Bearden et al., Reference Bearden, Netemeyer and Teel1989; van den Putte et al., Reference van den Putte, Yzer and Brunsting2005; Bond et al., Reference Bond, Fariss, Jones, Kramer, Marlow, Settle and Fowler2012; Christakis and Fowler, Reference Christakis and Fowler2013; Doherty and Schraeder, Reference Doherty and Schraeder2014; Araujo et al., Reference Araujo, Neijens and Vliegenthart2017; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Fam, Goh and Dai2018). Social contagion works independently of mobilizing communication, the actions of organizations, people’s participation in civic or political groups, and other customary predictors of political behavior (Doherty and Schraeder, Reference Doherty and Schraeder2014). It is sometimes explained in terms of a basic tendency toward imitation or mimicry. This tendency has a biological basis that is not only universal across national contexts but is even found in other primates (Chartrand and Bargh, Reference Chartrand and Bargh1999).

Distinctions among social influence pathways that are more and less contingent on context and behavior are often not sharp in practice because these so often co-occur. A good example is the case of cessation of smoking, an important public health goal in many countries. People are induced to stop smoking both by awareness of the behavior of others (i.e. ‘I stopped smoking because a lot of other people have done so’) and by awareness of injunctive social norms against smoking (i.e. ‘I stopped smoking because stopping is a good thing to do’) (van den Putte et al., Reference van den Putte, Yzer and Brunsting2005). In some cases, the norms driving social influence are themselves widespread, as in the case of reciprocity and conditional cooperation (Fehr and Fischbacher, Reference Fehr and Fischbacher2004). When people act in ways that are visible to others, they may simultaneously convey useful information that shapes others’ evaluation of whether to act, prime the tendency in others to protect social reputation, and induce a tendency for mimicry.

Outside of well-controlled experimental conditions, parsing out the relative contributions from different social influence pathways is typically not a tractable problem. This is true for survey-based designs, where the need to measure a close proxy to social influence is necessary, and where it is not possible to disentangle which pathways are present in what degree (Doherty and Schraeder, Reference Doherty and Schraeder2014). Our concern in the present study is whether social influence is detectable across diverse national contexts and behaviors. This concern resolves into a problem of understanding whether the universal pathways of social influence are sufficiently strong to be measurable across diverse national contexts and behaviors.

The empirical literature on specific behaviors in a single-country context (or a small number of countries) suggests that some degree of universality is likely present. The list of political actions that have been shown in at least one country to be subject to social influence is long, including voting, donating, petition-signing, campaign activities such as contacting others, and various forms of cooperative behavior such as recycling (Leighley, Reference Leighley1990; Huckfeldt and Sprague, Reference Huckfeldt and Sprague1995; Gerber and Green, Reference Gerber and Green2000; Arceneaux and Nickerson, Reference Arceneaux and Nickerson2008; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Green and Larimer2008; Nickerson, Reference Nickerson2008; Bond et al., Reference Bond, Fariss, Jones, Kramer, Marlow, Settle and Fowler2012; Sinclair, Reference Sinclair2012; Margetts et al., Reference Margetts, John, Hale and Yasseri2016; Bhatti et al., Reference Bhatti, Fieldhouse and Hansen2020). Social influence on political consumerism has not been reported, to our knowledge, but likely exists (Antonetti and Maklan, Reference Antonetti and Maklan2016) because consumer behavior generally is subject to social influence (Burnkrant and Cousineau, Reference Burnkrant and Cousineau1975; Bearden et al., Reference Bearden, Netemeyer and Teel1989).

The first of our two criteria for universality is the presence of effects across diverse national contexts. A straightforward way to operationalize this criterion is with a set of countries that collectively exhibit a high degree of variation along multiple comparative dimensions. For this task, we employed a list of countries that vary in democratic context (i.e. established democracies, democracies in peril, and not fully democratic countries), primary religious tradition, and political culture (Sivakumar and Nakata, Reference Sivakumar and Nakata2001). When we applied these criteria to selecting countries, the result was variation on other important dimensions, including type of media system, party systems and electoral arrangements, and opportunities for political participation. The list is: Argentina, Brazil, China, Estonia, Germany, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Philippines, Poland, Russia, Spain, Taiwan, Turkey, UK, Ukraine, and the USA. We use this as a test set for social influence across diverse national contexts, but we do not attempt to theorize specific variation among these countries. To the extent social influence is present across this set as a whole, we consider the criterion for diverse national contexts to be satisfied.

The second criterion for universality is effects across political behaviors. Our approach is to examine four classes of behavior. Without resolving the long-standing debate over the classification of political behavior (Cantijoch and Gibson, Reference Cantijoch and Gibson2013), we identify a sufficiently broad set of behaviors to ensure that whatever relationships we find are not behavior-specific. We start with voting as a baseline act, and then add three distinct classes of behavior. The first is political consumerism, which is boycotting goods or services for political reasons, and its companion, buycotting, the intentional purchase of goods or services for political reasons (Copeland, Reference Copeland2014). These are private acts undertaken in the marketplace, unstructured by the state, and not subject to the same set of civic norms as voting (Dalton, Reference Dalton2008). Next, we include political expression. Following Hamlin and Jennings (Reference Hamlin and Jennings2011), we conceptualize expression in terms of contacting public officials and publicly displaying messages. Last, we consider engagement, which we conceptualize in terms of an index of diverse acts: participating in protests and marches, donating money, and engaging in local social and political action. To the extent that social influence is present across these four classes of participation, we consider it to have met the criterion for effects across diverse behaviors. Combining our expectations about the two criteria for universality produces our primary hypothesis.

Social influence is associated with political expression (H1a), political consumerism (H1b), public engagement (H1c), and voting (H1d) across the set of 19 politically heterogeneous countries.

Heterogeneity of social influence effects: the case of age

To the extent that social influence is universal, it is might be moderated by universal variables. Research on moderators of social influence on political behavior is very limited and the theoretical terrain is wide open. Studies of social influence on voting behavior and petition-signing have not found education or geography to be a moderator (Fieldhouse et al., Reference Fieldhouse, Cutts, John and Widdop2014; Margetts et al., Reference Margetts, John, Hale and Yasseri2016; Bond et al., Reference Bond, Settle, Fariss, Jones and Fowler2017).

One variable stands out as a potentially intriguing moderator: age. Age has a broad and varying relationship to political behavior and to norms of citizenship and participation across countries (Grasso, Reference Grasso2014; Bolzendahl and Coffé, Reference Bolzendahl and Coffé2013; Melo and Stockemer, Reference Melo and Stockemer2014; Hooghe and Oser, Reference Hooghe and Oser2015). The literature in social psychology suggests that younger people are more susceptible to social influence in many situations due to age-related variation in orientation toward peers, concern with others’ judgment, reliance on knowledge, and belief stability (Pasupathi, Reference Pasupathi1999; Steinberg and Monahan, Reference Steinberg and Monahan2007).

However, most of the empirical work showing decreased susceptibility to social influence with age comes from studies of behavior remote to politics, such as smoking (Castro et al., Reference Castro, Maddahian, Newcomb and Bentler1987), the Asch line length task (Pasupathi, Reference Pasupathi1999), product adoption in Facebook networks (Aral and Walker, Reference Aral and Walker2012), and sexual behavior (White et al., Reference White, Terry and Hogg1994). How this effect extends to politics is not clear. Murray and Matland (Reference Murray and Matland2015) find that younger adults have less reactance against social pressure campaigns in voting. Bond et al. (Reference Bond, Settle, Fariss, Jones and Fowler2017) show the opposite, namely that susceptibility to social influence on voting increases with age in a population of USA Facebook users. At this point the empirical picture about age and social influence in politics is ambiguous. This leads us to an exploratory question about age:

Does age moderate the effect of social influence on political behavior across countries?

Design considerations and methods

Testing expectations about effects of social influence across countries and actions presents a considerable challenge for research design. The approach must prioritize comparative analysis and multiple outcome variables, which are well suited to survey designs. However social influence cannot be measured directly in surveys, so a proxy must be relied upon. Endogeneity problems are potentially great: political homophily in social networks means people are likely to affiliate with others who believe and also behave like they do. Also, people who are more participatory may be more aware of the actions of others and to recall these when asked.

In this study we take on these challenges. As a proxy for social influence, we measure respondents’ self-reported awareness of others’ political actions, which is similar to the approach of Doherty and Schraeder (Reference Doherty and Schraeder2014). We focus on proximate others in the form of friends, family, and acquaintances, in order to capture influence from both strong-tie and weak-tie networks, but not the influences of mass behavior. We expect these networks to be the locus of universal components of social influence. This measure does not explicitly tap respondents’ understanding of specific behavioral norms that vary with country and action, such as the duty to vote or the value of voluntarism.

To address endogeneity between awareness of others’ actions and self-reports of respondents’ own behavior, we take several steps. First, we exploit a two-wave panel design that allows us to include Wave 1 values of each participation measure as controls for predicting Wave 2 values. This provides control for the effects of homophily in social networks, because effects of affiliating with others who participate similarly will be reflected in the Wave 1 measures. In Wave 2 we capture effects of awareness of behavior of others. We include controls for size of political discussion networks and frequency of political discussion, which also capture effects of affiliation with behaviorally similar people as well as biased recall associated with political conversations about political affairs.

Our analysis uses pooled samples from our 19 countries in the Americas, Asia, and Europe (see above, and the Online Appendix, Tables A1, A2, and A3), which we selected for political heterogeneity. To secure comparability and reliability across different languages, the researchers generated a group of experts and translators who were involved in the study from the beginning and performed the translation of all items. Afterwards, the surveys were translated employing either back-translation with a team approach (Behling and Law, Reference Behling and Law2000; Thato et al., Reference Thato, Hanna and Rodcumdee2005), or the committee approach (Brislin, Reference Brislin, Triandis and Berry1980). Survey administration was performed by the Media Innovation Lab (MiLab) at University of Vienna using the Qualtrics survey platform. Wave 1 data was gathered concurrently in all countries from September 14 to 24, 2015. Overall, the cooperation rate was about 77% across the panel (AAPOR, 2011; CR3). Wave 2 was gathered 6 months later, with a cooperation rate of over 57%. After performing a Missing Values Analysis, we deemed missing cases to be at random and used pairwise deletion of missing cases in the regressions.

The researchers partnered with Nielsen, the popular media polling company based in the USA, which curates and maintains a massive pool of 10 million potential respondents across most countries globally. From this pool, Nielsen created a final sample in each country based on stratified quota sampling techniques that produced samples with demographics closely matched to those reported by official census agencies (see Callegaro et al., Reference Callegaro, Baker, Bethlehem, Göritz, Krosnick and Lavrakas2014). The largest sample was collected in Ukraine (n = 1,223), and the smallest in Korea (n = 943). The overall mean sample size for all countries was just over a thousand cases per country (M = 1,067; SD = 238). Since Nielsen partners with companies that employ a combination of panel and probability-based sampling methods, the limitations of web-only survey designs are minimized (Bosnjak et al., Reference Bosnjak, Das and Lynn2016). However, some parameters of the panel invites are unknown, and therefore traditional response rates are not calculated (AAPOR, 2011; [Gil de Zúñiga et al., Reference Gil de Zúñiga, Ardèvol-Abreu, Diehl, Patiño and Liu2019]; also see Online Appendix, Tables A1, A2, and A3).

Measures: dependent variables

We employed four dependent variables to test the a, b, c, and d parts of our hypothesis: political expression, political consumerism, public engagement, and voting. All measures of the dependent variables exist for both Waves 1 and 2.

Political Expression

Our variable for political expression includes two items. The first asked about frequency of ‘posting a political sign, banner, button, or bumper sticker,’ and the second about ‘contacting elected public officials.’ The index performed quite reliably across all countries (2 items averaged scale, Spearman-Brown ρ = .85, M = 1.94 SD = 1.39). The lowest reliability was in New Zealand (Spearman-Brown ρ = .73) and the highest in Japan (Spearman-Brown ρ = .95). Table 1 shows details for political expression, the other dependent variables, and also the independent variable, social influence.

Table 1. Descriptive and reliability statistics for independent and dependent variables

Note. All items measured on 7-point frequency scales. T-tests have been adjusted with Bonferroni normalization and bootstrapped (5,000 times). Social influence, political expression, political consumerism, and voting reliability tests are based on Spearman-Brown coefficient ρ rather than Cronbach’s α as these constructs include two items. * denotes p < .05 for difference between country mean and grand mean.

Political Consumerism

Our variable for political consumerism is also based on two questions. The first asked respondents how often in the past three months they ‘boycotted a certain product or service due to social or political values of the company,’ and the second asked about purposely buying a product for the same reasons. The two-item index had modestly good reliability (2 items, Spearman-Brown ρ = .79, M = 2.41 SD = 1.52). The lowest reliability test was in Estonia (Spearman-Brown ρ = .62) and the highest in China (Spearman-Brown ρ = .87).

Public engagement

Drawing on prior approaches to participation outside voting and political expression (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Brady and Schlozman1995; McLeod et al., Reference McLeod, Scheufele and Moy1999), we built an index from questions about how frequently respondents engaged in the following activities in the past three months: ‘attended or participated in a political rally, demonstrations, protests, or marches’, ‘donated money to a political campaign or political cause’, participated in groups that took any local action for social and political reform.’ This index performed reliably (3 items, with a twenty country Cronbach’s α = .92, M = 1.87, SD = 1.37). The lowest reliability (Cronbach’s α = .84) was in Argentina and the highest in Japan (Cronbach’s α = .96).

Voting

We measured voting with one question each about frequency of voting in ‘local’ and ‘national’ elections. Reliability was high (2 items averaged scaled, with a twenty country (Spearman-Brown ρ = .95, M = 5.38, SD = 2.06). The lowest reliability was in China and New Zealand (Spearman-Brown ρ = .88 and .89, respectively) and the countries with the highest (Spearman-Brown ρ = .98) were Japan and Philippines.

Measures: independent variable

Social Influence: Awareness of Others’ Actions

The main predictor in this study is respondents’ exposure to social influence in the domain of political activities. We used a proxy in the form of awareness of others’ action built from two questions. The first inquired about how frequently people around the respondent, namely friends, family or acquaintances, got involved in ‘political issues’, and the second asked about how frequently people around the respondent got involved in ‘political activities’ such as attending rallies, donating money for a political campaign, and voting, etc. The two-item index had solid reliability (2 items averaged scaled, with a twenty country (Spearman-Brown ρ = .86, M = 2.43, SD = 1.47). The lowest reliability (Spearman-Brown ρ = .71) was in Estonia and the highest in Germany and Spain (Spearman-Brown ρ = .92 and .91, respectively). We measured this variable at Wave 1.

Measures: controls at the individual and country level

Demographic variables

As controls, we measured age (M = 41, SD = 14.64), gender (female = 1, 51%), education (using an eight-point scale where 1 = none and 7 = postgraduate degree; M = 4.34, SD = 1.30), income (annual household income, M = 2.94, SD = 1.1); and ethnicity as a binary variable for majority or minority (majority = 1 with 86%). All controls are measured at Wave 1. For a comparison between all our demographic variables and census data for each country, see online Appendix Table A1.

Socio-political antecedents

We use a standard set of attitudes and proto-political antecedents, all employing a 1-to-7 Likert scale unless otherwise stated. This first is frequency of news use with multiple items that capture the exposure to news and public affairs from ‘printed newspapers’, ‘local or cable TV’, ‘online news websites’, ‘radio’, ‘social media’, ‘citizen journalism sites’, and ‘people’s word of mouth’ (7 items, α = .68, M = 4.42, SD = 1.02). The second is internal political efficacy, measured by averaging two items tapping the extent to which ‘people like me can influence the government’, and ‘I consider myself well qualified to participate in politics’ (Spearman-Brown ρ = .71, M = 3.49, SD = 1.49). Similarly, external political efficacy captured the degree to which ‘people like me don’t have any say in what the government does’, and ‘no matter whom I vote for, it won’t make a difference’ (2 items recoded, Spearman-Brown ρ = .58, M = 7.36, SD = 1.54). We also controlled for the potential confounding effect of size of discussion network and the frequency of political conversations. The former included a question where respondents estimated how many people they had discussed politics with in the past month, face-to-face. As expected, the outcome was highly skewed (Skewness coefficient = 17.48, SE = .018, M = 6.65, SD = 20.39) so we calculated the natural logarithm (M = .59, SD = .45). Frequency of political discussions used an additive scale of items that registered political discussions with closer-knit networks (‘spouse or partner’ and ‘family, relatives, or friends’), as well as political conversations with loose, weak ties (‘acquaintances’ or ‘strangers’) (4 items, α = .82, M = 3.37, SD = 1.38). Finally, we controlled for how ideologically extreme subjects were by measuring where they would place themselves on ‘political issues’, ‘economic issues’, and ‘social issues’ (3 items each with a scale ranging from 0 to 10 (strong liberal to strong conservative), and folded 0 to 5 (α = .89, M = 1.59, SD = 1.70).

Country Gross Domestic Product

We included a variable for per capita GDP to control for economic effects, drawn from 2016 World Bank figures in thousands of dollars (M = 21, SD = 15, Min/Max = 2/57).

Country Individualism or Collectivism

Because we are interested in social influence in collective behavior, we wished to control for level of individualism versus collectivism in political culture. We used an individualism measure from Hofstede’s conceptualization, taken from data reported at Hofstede Institute’s website (see, e.g. Hofstede et al., Reference Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov2010) (M = 48.14, SD = 23.94).

Democracy Scores

We also control for two other potentially important country-level variables relevant to democracy (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Lindberg, Skaaning and Teorell2016). The first of these is V-Dem score (M = 0.82, SD = 0.22) from the Varieties of Democracy project at the University of Gothenberg, which scores quality of democracy. The other is freedom of the press (M = 39.8, SD = 20.74), from Freedom House (Dunham, Reference Dunham2016).

Approach to analysis and modeling

We first present descriptives for key variables in the study, including t-tests for differences, as shown in Table 1. For most of the countries, Leven’s test for homoscedasticity yielded statistically significant results, so in those cases we adjusted the degrees of freedom employing the Welch-Satterthwaite method (Willink, Reference Willink2007). Additionally, given the multiple t-tests, we bootstrapped all calculations with 5,000 iterations (Mooney and Duval, Reference Mooney and Duval1993). A good deal of variation is present here, especially in voting. Argentina, Estonia, and Turkey show the highest voting levels, with China, Russia, and Ukraine roughly a standard deviation below them at the bottom. For political expression, political consumerism, and public engagement, nearly all individual country means differ from the grand mean.

For the main analysis below, we run autoregressive ordinary least squares regressions for each of the four dependent variables with the countries pooled and also for each country individually. For the pooled models, we start with individual-level predictors and then add our four country-level controls. We exploit the panel structure to control for Wave 1 levels of the dependent variables when predicting the Wave 2 values, introduced as an autoregressive term.

Results

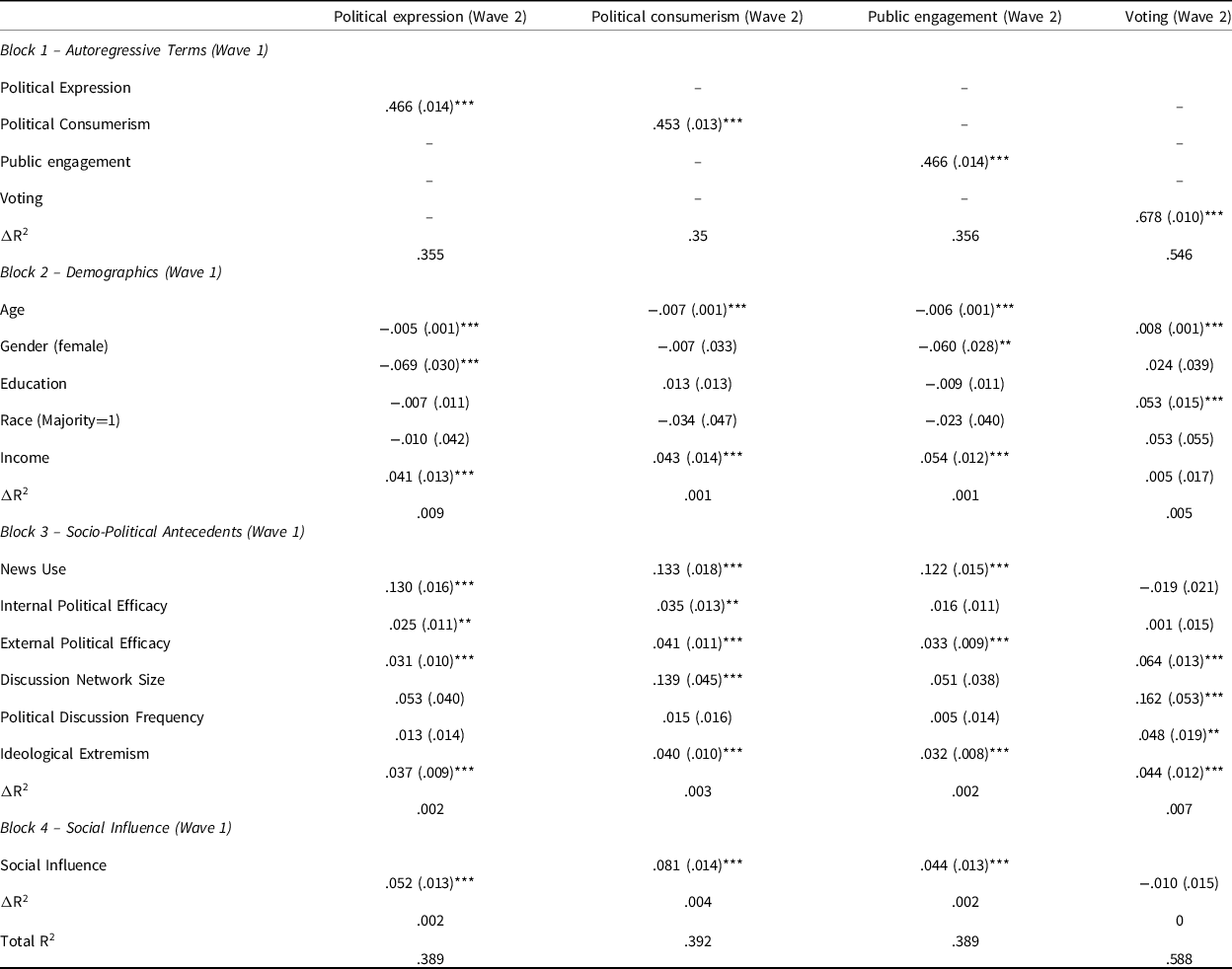

The regression results provide support for our expectation that social influence is positively associated with political expression (H1a), political consumerism (H1b), and public engagement (H1c). All four models yield good predictive power, with R2 ranging from .39 to .59. As Table 2 shows, the strongest effect is for political consumerism (b = .081, se = .014, p < .001), followed by political expression (b = .052, se = .013, p < .001) and then public engagement (b = .044, se = .013 p < .001). We do not find a relationship for voting (H1d; b = −.010, se = .015, p = .489).

Table 2. Individual-level pooled autoregressive OLS regression models predicting political behavior

Note. N = 4,901. Cell entries are final-entry OLS unstandardized coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Measures of the effects of social influence potentially suffer from endogeneity due to political homophily in social networks: people who participate more are also likely to associate with others who participate, to talk about politics with them, and to remember others’ participatory actions. Our model includes three controls aimed at addressing this problem. The first is prior level of participation, measured in Wave 1. The others are frequency of political discussion and network size, which should capture additional effects from participatory habits leading to greater association with others who are participatory, from discussion, and from better recall.

The Wave 1 values of the dependent variables are the strongest predictors of the Wave 2 values, as expected. This relationship is strongest for voting (R 2 = .59), while the other three variables are similar in predictive power as follows: political expression (R 2 = .36), political consumerism (R 2 = .35), and public engagement (R 2 = .40). Some noteworthy relationships exist among the control variables. Education is predictive of voting, which is consistent with many comparative findings on political behavior, while it is not predictive of expression, consumerism, or engagement. Age is positively related to voting, but negatively related to the other forms of participation.

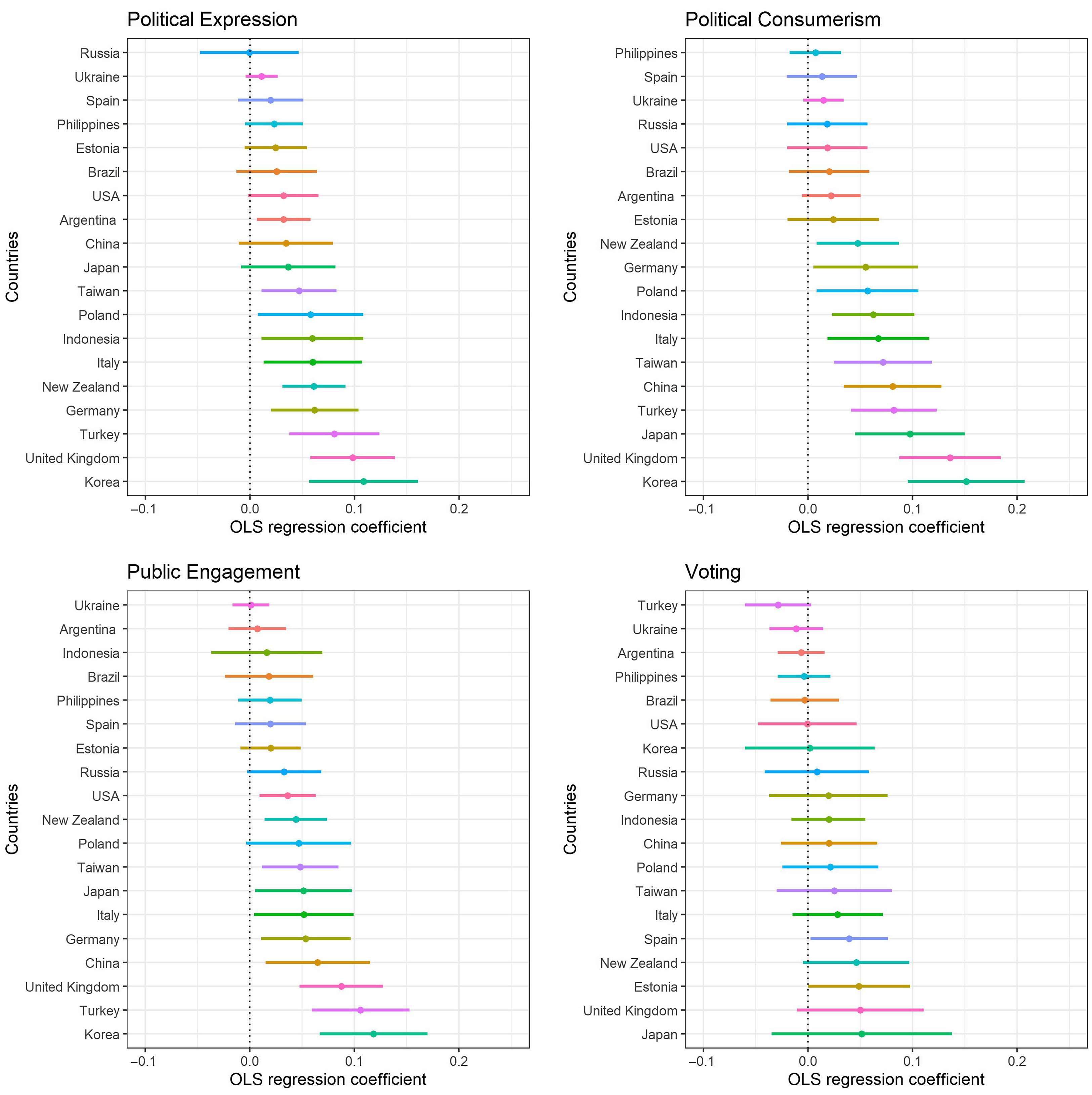

Country-level differences and multi-Level models

We also conducted a basic exploration of country differences, although we do not have country-specific hypotheses. To do this, we ran models independently for each country, predicting Wave 2 values of the dependent variables from social influence and the autoregressive term in Wave 1. The results, which are shown in Table 3, characterize the distribution of social influence effects across countries. We also show the county-specific coefficients and confidence intervals graphically in Figure 1. With the exception of voting, where we see social influence effects only in Estonia and Spain, we find effects for all the dependent measures in about half the countries, and an effect for at least one dependent measure in 16 of the 19 countries, with the exceptions being Brazil, the Philippines, and Ukraine. Topping the list of countries showing the strongest social influence effects for expression, consumerism, and engagement are the UK, Turkey, and South Korea.

Table 3. Social influence coefficients predicting political participation by country

Note. Cell entries are unstandardized OLS coefficients for social influence in autoregressive models predicting each dependent measure at Wave 2, with standard errors in parentheses. Models include the Wave 1 terms as predictors for Wave 2.

# p < .10; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Figure 1. OLS Regression Coefficients for Social Influence in Predicting Political Expression, Political Consumerism, Political Public Engagement, and Voting by Country.

Note. Unstandardized OLS coefficients in autoregressive models for social influence predicting Wave 2 values by country, for Political Expression, Political Consumerism, Political Public Engagement, and Voting, with 95% confidence intervals.

Our expectation was that social influence effects would be present across countries that are heterogeneous with respect to important comparative variables. The results support this expectation. The UK is a consolidated Western democracy with two-party, majoritarian electoral politics. Turkey is one of the world’s leading autocratizers, is generally no longer considered a full democracy, and has a history of constitutional changes and a military coup as recently as 1980. Its culture is noted for its blending of Mediterranean, Western and Central Asian, and Eastern European influences. South Korea is a robust democracy with a pluralistic, multi-party system and a collectivist culture rooted in Confucianism. Similar variety occurs across other countries.

To examine country effects further, we tested the null hypothesis for differences across countries. We employed fixed-intercept models for the four dependent variables and compared these to random intercept models with no other predictors – null models. As expected, the difference in the log likelihood ratio was statistically significant, so we rejected the null hypothesis of no variation among countries. We then proceeded with multi-level models with our four controls for macro-level variables: per capita GDP, collectivism/individualism, V-Dem score, and the freedom of the press. The results are robust to these controls and are shown in Table 4 as well as Figure 1. In these multi-level models, social influence still predicts political expression (b = .055, se = .016, p < .001), political consumerism (b = .088, se = .018, p < .001) and public engagement (b = .051, se = .016, p < .001), but not voting (b = .025, se = .020, p = .188). The random intercept log likelihoods vary the least for the political expression model (Log Likelihood = 9,698.4) and the highest for voting (Log Likelihood = 11,846.3).

Table 4. Multi-level autoregressive models of socially influenced participation

Note. N = 3,490. Based on 19 groups. Cell entries are unstandardized OLS coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. # p < .10; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. Significance levels for random effects based on Wald tests. All independent variables are from Wave 1.

The variance of the random component indicators accounts for differences among countries except for the model predicting the public engagement index (Between Countries

![]() $\sigma _u^2$

: political expression = .016, p < .05; political consumerism = .015, p < .05; and voting = .037, p < .05). The country-level controls do not exhibit many noteworthy relationships. None of the four predict political expression, political consumerism, or voting. V-Dem (b = .610, se = .288, p < .05), and freedom of the press (b = .007, se = .0103, p < .05) predict public engagement.

$\sigma _u^2$

: political expression = .016, p < .05; political consumerism = .015, p < .05; and voting = .037, p < .05). The country-level controls do not exhibit many noteworthy relationships. None of the four predict political expression, political consumerism, or voting. V-Dem (b = .610, se = .288, p < .05), and freedom of the press (b = .007, se = .0103, p < .05) predict public engagement.

Our research question asked whether age moderates the relationship between social influence and the four measures of participation, and if so, in which direction. We ran our pooled models with an interaction term: age x social influence. For simplicity, given varying age distributions and generational breakpoints across countries, we used a simple younger/older measure of age defined with a breakpoint at the mean. This measure interacts positively with social influence for political expression (H2a; b = .0023, se = .00008, p < .001), political consumerism (H2b; b = .0025, se = .00009, p < .001), public engagement (H2c; b = .0022, se = .00008, p < .001) and also for voting (H2d; b = .0026, se = .00013, p < .001). We display this in two ways. Figure 2 shows the direction of the interaction for younger and older respondents, with social influence at its mean and also a standard deviation above and below the mean. All differences are significant. Figure 3 displays the above unstandardized beta coefficients with confidence intervals. The contribution of the interaction terms to explained variance is about 3–4% for political expression, political consumerism, and public engagement, and 1.8% for voting, which is greater than the contributions of the demographic and socio-political antecedent blocks of variables. Older people exhibit a larger social influence effect than younger ones.

Figure 2. Interaction of Age and Social Influence in Predicting Public Engagement, Political Consumerism, Political Expression, and Voting For Young and Old, at Three Values of Social Influence.

Note. Graphs show conditional effect of social influence on the dependent variables, with social influence at its mean, at one standard deviation above (High) and one standard deviation below (Low). Young = age below the mean; Old = age above the mean.

Figure 3. Interaction of Age and Social Influence in Predicting Public Engagement, Political Consumerism, Political Expression, and Voting with Confidence Intervals.

Note. Graph shows conditional effect of social influence on the dependent variables with confidence intervals.

Discussion and conclusion

We began this study with an interest in bringing together the widely accepted idea that social influence is a human universal and the study of political behavior. We posited that among the ways that people influence one another’s political behavior should be a set of pathways with a high degree of universality across national contexts and political behaviors. We built a model for predicting political behavior using autoregression in a two-wave panel survey with a wide range of individual-level and country controls. Our proxy measure for social influence adds explanatory power to this model across a diverse set of countries and many behaviors – but not all.

The aggregate predictive effect across countries is comparable in magnitude to that of age, and greater than that of income, gender, efficacy, and ideological extremism. This is true for political expression, political consumerism, and public engagement, and it constitutes our primary conclusion: Social influence shows average effects across diverse countries and behaviors, and the magnitude of these effects are comparable in size to those of important standard predictors of diverse political behavior.

We did not find an effect for voting. This is less surprising than it might appear. In this study we measured people’s perceptions that others in their social networks are engaged in public affairs. We sought to capture naturalistic influence occurring regularly between people. The well-known results from GOTV voting studies in the USA, by contrast, measure a different independent variable, namely exploitation of social pressure by political organizations (e.g. Gerber and Green, Reference Gerber and Green2000; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Green and Larimer2008). Those studies employ a very strong treatment in which the experimenters present subjects with information about the voting behavior of others, or threaten public disclosure of whether subjects voted, or both – which incidentally would violate some countries’ privacy laws. Our null findings about naturalistic social influence on voting are compatible with GOTV field experiments testing the effects of strong, organized social pressure campaigns. Our findings are also consistent with the results of Bond et al. (Reference Bond, Fariss, Jones, Kramer, Marlow, Settle and Fowler2012) and Jones et al. (Reference Jones, Bond, Bakshy, Eckles and Fowler2017). Their treatments involved a form of naturalistic social influence among peer networks and so are closer to our own survey measure. Their high-power experiments find an increased probability of voting of about 0.2% due to social influence, which is smaller by more than an order of magnitude than the 8.1% GOTV treatment effect in Gerber et al. (Reference Gerber, Green and Larimer2008). Their effect is too small for detection in survey studies with country samples of conventional size, such as our own.

A secondary goal of the study was to shed light on whether age moderates the main effects of social influence and in which direction. The literature has not resolved whether age is a moderator of social influence, and if so, whether the effect is positive or negative. Our results show age to be a robust moderator across actions in the positive direction. Social influence is stronger among older people than younger ones. This makes social influence in politics potentially distinctive from some other domains such as culture, where younger people tend to influence one another more. Future research may further investigate theoretically meaningful age variables, such as those tapping generational distinctions. It is plausible to think that an inertia effect might exist, as older adults beyond their early political socialization in adolescence and youth may be less responsive to social influence. Similar findings in terms of the role of technology on political behaviors have been previously suggested (Bachmann et al., Reference Bachmann, Kaufhold, Lewis and Gil de Zúñiga2010; Grasso, Reference Grasso2014).

We set out to examine the extent to which social influence effects are present across diverse countries, but we did not attempt to theorize an explanation of variation across countries. Social influence works through multiple pathways, typically in combination. Some of these are contingent on the behavior in question and on contextual factors such as political culture and participation opportunities, while others are theoretically independent. We designed our study to test for social influence independent of a country-level context but not to explain variation. It is an interesting and challenging problem for future research to develop country-level theories of social influence that could explain what variation exists in the general trends we find here. Our finding that social influence is present across countries as diverse as the UK, Turkey, and South Korea supports our basic expectation and suggests that measuring social influence effects consistently across countries is a tractable problem. We do not see effects for every behavior in each of the 19 countries. There are three outlier countries with no effects on any of the behaviors: Brazil, Philippines, and Ukraine. There are also various country-behavior pairs without effects. This variation on the overall finding is a promising jumping-off point for future research. We ruled out four possibilities for country-level confounds in our multi-level models: cultural collectivism, GDP, V-Dem democracy score, and Freedom House press freedom score. Future theorizing might develop these and other potential contributors to variation in social influence effects at the country level.

One of the assumptions in our approach was that social influence cannot be reduced to the individual-level attributes and resources typically found in models of political behavior (Margetts et al., Reference Margetts, John, Hale and Yasseri2016). Our findings are robust to controls for many standard predictors of behavior, as well as discussion network size, frequency of political discussion, internal and external efficacy, and the first-wave measures of participation. We are persuaded that social influence is a distinct concept and that asking about perceptions others are acting can be a useful survey measure for tapping it.

Explaining individual-level variation in susceptibility to social influence is a wide open endeavor in political science and may be more promising theoretically than explaining country-level variation. In this study, we focused on age as a potentially universal moderator at the individual level. In our models without an interaction term, the effect of age is positive for voting and negative for the other forms of participation. When we include the interaction term, age moderates the effect of social influence in the positive rather than negative direction. Where age is concerned, social influence in political behavior may differ from that in non-political actions. This result suggests that care should be taken in interpreting the results of experimental designs employing students or other age-restricted subject pools to study social influence in political behavior.

Future work should consider other individual-level moderators. Margetts et al. (Reference Margetts, John, Hale and Yasseri2016) find moderating effects on petitioning from Big-5 personality measures, which we do not address in the present study. Gender has also been found to moderate social influence effects in many studies outside politics, and further research might address this as well.

The importance of understanding social influence is likely to grow in the future. The ongoing transformation of the media environment is greatly expanding people’s opportunities to send and receive social signals. Through social media, people can observe one another’s political intentions and actions in ways that greatly surpass what is possible through mass media and face-to-face interactions. More social signals should entail more social influence. We anticipate that a fuller understanding of contemporary political behavior requires attention to this fact. Our results suggest that behavioral scholars may benefit from adding measures of social influence to their tool kit, since a reasonable presumption is that effects are likely to be present in a diversity of contexts and for many behaviors.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S175577392200008X.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by Grant FA2386-15-1-0003 from the Asian Office of Aerospace Research and Development. The authors are indebted to Prof. Liu and all other World Digital Influence Project participants, who helped in the data collection of these data. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this study lies entirely with the authors.

The second author has benefited from the support of the Spanish National Research Agency’s Program for the Generation of Knowledge and the Scientific and Technological Strengthening Research + Development Grant PID2020-115562GB-I00. He is also funded by the ‘Beatriz Galindo Program’ from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation & Universities, and the Junta de Castilla y León

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.