Introduction

It is well known that early modern English guilds did not enjoy the power to compel every trader in a region to join (as their Japanese counterparts often did, for example).Footnote 1 Nevertheless, exactly when and how the guilds in England lost this power remains a matter of contention. Classic works such as those by Unwin and Landes depicted the decline of guilds in the course of the seventeenth century – a model referred to in the following pages as the ‘old orthodox chronology’.Footnote 2 On the basis of studies conducted since 1985, by contrast, Epstein argued for guild decline during the eighteenth century (the ‘new orthodox chronology’). As a major provincial town, Exeter has attracted a number of classic studies, including those by Hoskins and Youings.Footnote 3 However, these were published before the advent of the new orthodox chronology, and the current study aims to place the case of Exeter within the context of this more recent historiographical perspective.

This article proceeds as follows. The first section considers recent historiographical debates concerning the decline of English guilds, and stresses two trends inconsistent with the new orthodox chronology: a perspective emphasizing the transformation rather than the decline of guilds per se, and the recent appearance of a number of studies on workers outside the guild in London. As we shall see, these trends have not received due attention in relation to the case of Exeter.

The second section is a case-study of guild decline in Exeter based on established empirical sources. It combines the name data used in classic studies of the Tuckers’ Company in Exeter.Footnote 4 First, it explores the relationship between citizenship and guild membership and examines the increase in the number of citizens operating outside the guild, namely citizens who were not guild members. More specifically, it shows how the increase in the number of citizens outside the guild outstripped increases in guild membership, despite the fact that most new citizens of Exeter were not migrants. It will be shown that this process occurred within the context of the decline of royal power, which had supported guild regulations favouring membership. Finally, we will discover that motivation to join the guild following its loss of monopoly proceeded primarily from its charities, which were founded first and foremost by the ascendant class of merchant fullers.Footnote 5 Amassing considerable wealth after the decline of the royal chartered company's monopoly on French trade, the merchant fullers became City Fathers and masters of the guild, and they supported the policy of increasing the number of fullers in Exeter in order to lower the wholesale price of cloth.

The historiography of English guild decline: the ‘old’ and ‘new orthodox’ chronologies

Controversies concerning the decline of guilds in England

Arguably one of the most important contributors to the recent debate about guilds, Epstein has noted that while there were no contemporary surveys of early modern English craft guilds or apprenticeship, a consensus has formed since 1985 which tends to push the decline of craft guilds forward into the mid- to late eighteenth century. He attributes the debate about whether the craft guilds began to decline in the latter part of the seventeenth century or afterwards to Snell's and Walker's works of 1985.Footnote 6

As Snell's and Walker's works constitute something of a milestone, a brief review of them is in order here. Sharply criticizing the old orthodox chronology, Snell argued that limited evidence from London was being ‘generalized to cover the whole country’.Footnote 7 Thus, differences in chronology between the mercantile guilds in the London livery companies and the craft guilds in provincial towns had been obscured. In Snell's view, despite the mid-seventeenth-century decline of London livery companies on which the old orthodox chronology had chiefly rested, most craft guilds in provincial towns persisted into the eighteenth century.

To reinforce this argument, Snell referred to Walker's work.Footnote 8 This dealt with eight guildated towns, including London and the main provincial towns such as Bristol and Exeter. Walker measured decline and guild control chiefly by using annual figures for guild membership from 1650 onward; he found that peak membership was reached around 1720.Footnote 9 He concluded that the experience of many London companies, apart from the majority of the Twelve Great Companies, was similar to that of the provincial guilds.Footnote 10

According to Epstein's aforementioned survey, the current consensus is based not only on Walker and Snell but also on works by Berlin, Gadd and Wallis – namely, studies on London produced since the 1990s. If so, we must revise Walker's conclusion. While Walker contended that livery companies did not function in any practical sense in late seventeenth-century London, the studies of Berlin, Gadd and Wallis suggest that they extended their control into the suburbs, particularly via the integration of non-members into London guilds in the later seventeenth century.Footnote 11

Thus, the current consensus which pushes the decline of guilds into the eighteenth century is, so to speak, the ‘new orthodox’ chronology. On the basis of this chronology, Epstein argued that the craft guild guaranteed apprenticeship contracts and functioned as the chief conduit for the transmission of skills during industrialization.Footnote 12 Does this mean that industrial development in England grew within rather than outside of traditional guild control or monopolistic restrictions?Footnote 13

A notable opponent of Epstein's perspective on this matter is Ogilvie, who portrays the stifling economic effects of guild regulations as an important contributing factor to the increasing disparity in early modern economic growth between Britain and the Low Countries on the one hand and the rest of Europe on the other. Following an old and influential liberal narrative, this disparity is ascribed by Ogilvie to the relative weakness of guilds in England and the Dutch Republic.Footnote 14 A key issue in this controversy is the definition of guild ‘strength’ and ‘weakness’.Footnote 15 These are most often measured in terms of a guild's political influence, its ability to regulate its own craft and hence – according to Ogilvie – its ability to enforce the innovation-killing conservatism of entrenched rent-seeking interests.Footnote 16 By contrast, Epstein also gauged guild strength in terms of the transmission of skills via craft apprenticeship. In his view, the combination of this function with the guilds’ political inability to enforce restrictive legislation gave eighteenth-century England a technological edge over the Dutch Republic, where economic growth had been founded upon the suppression of endogenous industrial innovation threatening the import trade, and where industrialization consequently took place at a relatively late date.Footnote 17

In fact, early modern guilds performed many functions. For example, they also served as religious fraternities, and in Exeter – as was the case in most English guilds – this function declined in the 1540s.Footnote 18 When considering controversies of chronology and guild strength in relation to the cloth trade of Exeter, this article will concentrate on the function of economic regulation, particularly as it concerns apprenticeship.

Another chronology and the workers outside the guilds

Before turning to the case of Exeter, there are two further significant issues arising from the new orthodox English historiographies which should briefly be considered. First, Berlin – whose work is one source of the consensus Epstein identified – pointed out that there are somewhat incompatible chronologies pertaining to the early modern period.Footnote 19 By contrast to the old orthodox chronology, for instance, Slack emphasized the transformation rather than the disappearance of guilds: following Clark, he asserted that guilds were losing their economic rationale and becoming clubs by the early eighteenth century.Footnote 20 This assertion was based on evidence from the ‘great and good towns’ or major county towns. If these are similar to the towns Walker called guildated towns, the first issue is: how does Slack's and Clark's chronology correspond to Walker's guildated towns?

The second issue concerns workers outside the guilds. Studies on London since the 1990s have examined the suburbs and workers outside the guilds – subjects Walker and Snell did not sufficiently consider.Footnote 21 Were there workers outside the guilds in provincial towns? And if there were, should we reconsider the meaning of the increase in guild members which Walker found in the later seventeenth century?

Citizen cloth-workers outside the guild and charity: the case of Exeter

These questions may be addressed by examining the Tuckers’ Company in the major provincial town of Exeter. We have already mentioned some classic studies above. Here, an attempt will be made to examine and compare their research by linking the name lists in the various documents they analysed.

Citizens and guild members

Walker's main argument with regard to English guild decline is that ‘even the dominant industries of a major provincial city could remain under guild control throughout the late seventeenth and eighteenth century’.Footnote 22 Exeter was certainly ‘a major provincial city’: it was the fifth largest town in England, with a population of more than 10,000.Footnote 23 Furthermore, the cloth industry was ‘the dominant industry’ in late seventeenth-century Exeter. As Hoskins has pointed out, in 1673 more than a third of the citizens were cloth traders.Footnote 24 In this historical context, citizens were not simply town residents but a select group of enfranchised citizens who enjoyed a monopoly on economic opportunity within the city; this ‘freedom of the city’ was primarily obtained by serving apprenticeships, by patrimony, by fee,Footnote 25 or by order of the mayor and town council. Institutionally, the distinction between citizens and non-citizens was clear-cut – the former were a minority (about 10 per cent of Exeter's local population during the period in question) with exclusive rights to carry on wholesale and retail trade.Footnote 26

While Exeter's cloth-working was its dominant industry, did it in fact remain under guild control? As only Walker has come to this conclusion, it would be prudent to examine his evidence, which comprises the membership figures for the Tuckers’ Company. This guild covered all the major activities of woollen manufacture and distribution, except perhaps wool-combing.Footnote 27 While there were several guilds for the various cloth-working occupations in early seventeenth-century Exeter, their boundaries were not clearly demarcated, and the Tuckers’ Company was the only one to receive a royal charter.Footnote 28

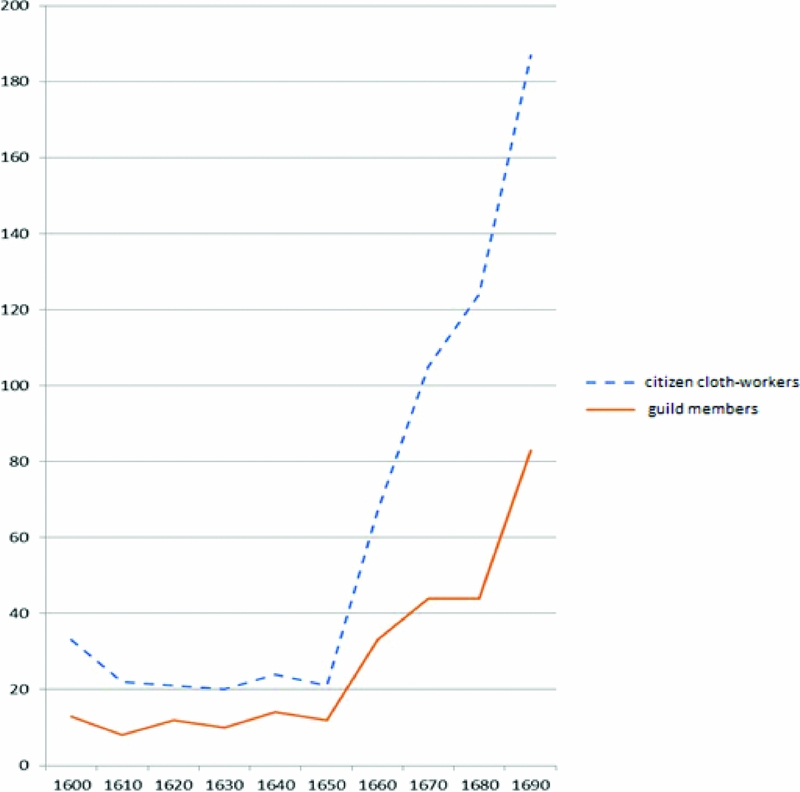

Looking at Figure 1 below, the solid line indicates the membership trend of the Tuckers’ Company.Footnote 29 As one can see, annual admittance to the company increased in the late seventeenth century, while the old orthodox chronology would predict the opposite trend. Clearly, the guild did not decline in the late seventeenth century – but does this mean that the cloth industry remained under guild control during this period?

Figure 1: Citizen cloth-workers and guild membership

Certainly, membership was an important element of the guild's control, but control also meant other things. In particular, it meant the ability to regulate quality and price, even among non-members. This regulation depended upon the extent to which members held a monopoly on their crafts, as Youings asserted.Footnote 30 And here, it is worth considering a further piece of evidence concerning Exeter citizens in the cloth trade. It is not new evidence, and it has already been analysed by Hoskins and others: some citizen cloth-workers were guild members but some were not, and from time to time the guild took action against citizen cloth-workers outside the guild.Footnote 31

In Figure 1, if the solid line representing annual guild admittance is ‘Walker's line’, then the dashed line by contrast is ‘Hoskins’ line’, showing the annual number of cloth-workers granted citizenship. In the late seventeenth century, both lines increased, but the dashed line increased more dramatically. As a result, although the number of guild members grew, they represented less than half the number of citizen cloth-workers in the late seventeenth century.Footnote 32

Does this mean there was a decline in guild control? As the upper row of Table 1 shows, the monopoly rate (i.e. the percentage of citizen cloth-workers who were also guild members) dropped, but not significantly. Let us focus the discussion on specific occupations. Citizens – both guild members (inside the guild) and non-members (outside the guild) were engaged in a variety of cloth-working occupations such as fulling, weaving and wool-combing. However, during the seventeenth century, around half of the citizen cloth-workers were fullers, while only approximately 15 per cent were weavers.Footnote 33

Table 1: Monopoly rate (guild members/citizen cloth-workers)

Sources: Rowe and Jackson, Exeter Freemen; Cresswell, First Minute Books; Cresswell, Minute Book 1618–1698.

Looking at the fullers, the lower row of Table 1 shows that the guild lost many of its most important members during this century. Fullers were the most important traders in the guild because they controlled the industry financially and owned fulling mills.Footnote 34 Additionally, many masters of the guild were fullers.Footnote 35 The guild's declining monopoly rate was a result of the expansion of citizenship into a wider pool of Exeter residents, and reflects the specific policy of the city authorities spearheaded by the merchant fullers (cf. infra). Hence, citizenship in Exeter saw a fourfold increase (from 122 to 491) in the course of the seventeenth century, yet there was a sevenfold increase in citizen fullers (from 41 to 292) in the same period, while the increase in non-fuller citizens was significantly less (81 to 199). Through the declining proportion of fullers in the guild relative to the overall number of fullers among Exeter's citizenry, it is likely the guild lost control of the cloth trade.

Even if the Tuckers’ Company still enjoyed substantial growth in the late seventeenth century, it is evident its power over the cloth trade diminished significantly, contrary to the new orthodox chronology. Still, the problem remains as to why the number of citizen cloth-workers outside the guild increased, and why there was a decrease of guild control. A consideration of previous studies of Exeter citizen cloth-workers outside the guild will help to clarify these issues.

Citizen cloth-workers outside the guild and migrants

The growth of citizens outside the guild is a key to understanding guild transformation in early modern Exeter. Though Youings did not specifically address this issue, she had the impression that there were few citizens outside the guild, and that most were migrant country craftsmen.Footnote 36 In the case of London, we know from studies since the late 1980s that the capital's population growth in the late seventeenth century required high levels of migration, and that there was a steady increase in the number of apprentices.Footnote 37 We also know that even though membership of one of the livery companies was required in order to be granted the freedom of the city, it is very probable that significant numbers of people were migrating to the city but not joining guilds.Footnote 38

Can we assume that a similar situation occurred in Exeter in the seventeenth century? As Walker and others have noted, the population of Exeter grew rapidly in the late seventeenth century: it was 9,400 in 1662, 10,650 in 1672, about 13,000 in 1688 and about 15,000 in 1750.Footnote 39 However, the factors underlying Exeter's growth were quite different from those in Stuart London. First, as Galley has pointed out, there were substantial natural increases in the population of Exeter in the seventeenth century.Footnote 40 A count – based on the abridged (decadal estimate of) parish registers – reveals a natural increase of approximately 5,000 people in Exeter over the century,Footnote 41 whereas there was a natural decrease of 512,000 people in London over the same period.Footnote 42 Secondly, in London one can observe an increase in the sex imbalance (m/f) in burial registers as apprentice immigration increased.Footnote 43 It is difficult to find similar data for seventeenth-century Exeter – based on the sex ratio of just two parishes, the numbers of men and women are nearly the same in the parish burial registers throughout the centuryFootnote 44 – but we can use the poll tax returns of 1660.Footnote 45 Based on these returns, the sex ratio of males to females was 0.93. This indicates a surplus of females, a common situation in pre-industrial towns.Footnote 46

Hence, while some citizen cloth-workers outside the guild may have been immigrants, as Youings asserts, most of them probably were not. And contrary to Youings’ view, citizen cloth-workers outside the guild were not ‘few’ in number in the late seventeenth century, as Figure 1 shows. That being the case, we must determine the reasons why the citizens outside the guild increased in number after the middle of the century.

The guild and royal authority

By its charter from the city in 1602, the Tuckers’ Company required basic entry fees (2s 6d) from apprentices, but extra fees from underqualified (for example, short-term) apprentices. If the extra fees were too expensive (sometimes more than 10s, over four times the basic fee), the apprentice had the right to appeal to the mayor, who would assess the amount according to his discretion. However, after the royal charter granted to the guild in 1620, the city chamber's right to regulate these extra fees was nullified, and apprentice appeals to the mayor ceased after that year.Footnote 47 As a consequence, the percentage of apprentices paying the basic entry fee increased markedly in the course of the seventeenth century, apart from a brief return to 1620s levels during the 1650s (see Table 2).

Table 2: Percentage of entries paying the basic fees

Sources: Cresswell, First Minute Books; Cresswell, Minute Book 1618–1698.

Stephens argued that the guild reduced the amount of the basic entry fee in the middle of the century in an attempt to attract fullers, who were increasing in number with the expansion of the industry; in his view, this led to a weakening in the apprentice system, as the guild stopped requiring extra fees from non-guild and underqualified apprentices, leading to an influx of such entrants.Footnote 48 While guild membership clearly increased in the late seventeenth century, Walker rejected Stephens’ thesis, arguing instead that the rapid expansion of the cloth trade from the middle of the century was the cause.Footnote 49 In support, he cited Youings to the effect that all members admitted in the late seventeenth century must have served apprenticeship.Footnote 50 Walker also refuted Stephens’ view on the grounds that the records only show the amount of the fee paid, making it impossible to distinguish between freemen who entered the guild by underqualified apprenticeship and those who entered by the basic entry fee alone.Footnote 51

As Table 2 shows, the basic entry fee became the standard for guild entrance in the late seventeenth century. If Stephens’ interpretation concerning an influx of underqualified entrants were correct, entry to the guild should have become easier, and the number of citizen cloth-workers outside the guild should have decreased. However, as noted above, citizen cloth-workers outside the guild actually increased in the late seventeenth century. Behind this trend lies the fact that some apprentices did not become guild members, but instead simply became citizens.Footnote 52 Thus, the number of citizen cloth-workers outside the guild increased at the same time as the extra fees charged by the guild decreased, as evidenced by Table 2. Footnote 53

Inevitably, the Tuckers’ Company complained to the city. Just after the Civil War, the guild made a petition to the city council on the matter of membership. Table 3 presents the answer provided by the recorder of the city council to the guild in 1651. It indicates that there were serious disputes between the city and the guild concerning citizen cloth-workers outside the guild and apprenticeship. It is likely that factions within the guild wished to reduce the number of citizen cloth-workers outside the guild.

Table 3: Tabulated version of answers from the recorder of the city council to the Tuckers’ Company in 1651

Source: Cresswell, Minute Book 1618–1698, 605.

Under law, the guild had several options available to achieve this aim (see points (c), (d) and (e) in Table 3).Footnote 54 However, in practice it only had recourse to option (d). This is because nearly 70 per cent of citizen cloth-workers gained the city freedom through their apprenticeship during the period 1650–91, as Table 4 reveals. What is more, nearly the same percentage of citizens inside the guild as those outside the guild became citizens in this way. As option (c) only permits the guild to punish citizen cloth-workers outside the guild who do not hold an apprenticeship, those with an apprenticeship (i.e. the majority) were not affected by this regulation.Footnote 55

Table 4: Cloth-workers’ mode of acquiring citizenship (1650–91)

Sources: Rowe and Jackson, Exeter Freemen; Cresswell, First Minute Books; Cresswell, Minute Book 1618–1698.

As for option (d), this rested on an appeal to royal authority, and was thus problematic after the Civil War. Petitioning the courts would probably have been in vain, for although the Interregnum courts continued to accept the legal validity of royal charters, they preferred royal charters confirmed by an act of parliament. While the Restoration period saw the highpoint of the role of royal charters, particularly during the 1680s, this role became increasingly politicized as royal authority faltered, and may have reflected a decline in interest in enforcing monopoly per se.

Thus, in the late seventeenth century, non-apprentices and the apprentices of citizen cloth-workers outside the guild could remain outside the guild, avoid paying the entrance fee and simply set up trade as citizen cloth-workers. This was an option that had not been open to them in the early seventeenth century, when royal authority and the means of penalizing non-members was still intact.

This implies that the reduction in the amount of the basic entry fee cited by Stephens may have been a result rather than a cause of the decline in guild apprenticeship after the middle of the century – while the primary cause may have been the declining effectiveness of the royal charter obtained by the guild in 1620.Footnote 56 This is why the number of citizen cloth-workers outside the guild increased and guild control decreased. Following the Civil War, not only the effectiveness of guild membership policy but also the policy itself changed drastically. As Youings points out, merchants generally favoured the expansion of the number of craftsmen in the cloth industry in order to keep the wholesale price of cloth as low as possible. Until the middle of the century, merchants controlled the city chamber only, while craftsmen controlled the guild and favoured a limit to the number of craftsmen.Footnote 57 However, in the late seventeenth century, certain rich merchants – chief among them being the merchant fullers – became masters of the guild and wanted an increase in craftsmen in the city, even if they came from outside the guild.

One more question remains: why did any cloth-workers join the Exeter cloth-workers’ guild once it had lost its monopoly after the middle of the seventeenth century?

Charities and merchant fullers

A comparison of the types of citizens who joined the guild with those who did not provides a useful starting point. As Figure 2 shows, there were in effect three categories of cloth-workers: citizen cloth-workers outside the guild, citizen cloth-workers inside the guild and non-citizen cloth-workers inside the guild.Footnote 58 It is possible to compare these three categories with three social strata – poor, middling and gentry – identified on the basis of the number of hearths.Footnote 59 A comparison of their social status reveals that the proportion of those of ‘middling’ status is effectively the same in all three groups, but that the non-citizens inside the guild included many more ‘poor’ and almost no ‘gentry’, while the largest proportion of ‘gentry’ numbered among the citizens inside the guild.Footnote 60

Figure 2: Social positions of citizens and guild members

Who were the ‘gentry’ within the guild? A number of studiesFootnote 61 have shown that the privileged royal chartered overseas trading companies declined from the mid-seventeenth century, and that certain merchant fullers of Exeter began to export cloth and became very rich as a result. Most of these merchant fullers were citizen cloth-workers inside the guild, and by the late seventeenth century they comprised about a third (17/52) of the guild's masters.Footnote 62 As they also comprised about half (21/50) of Exeter's mayors in the same period, they formed an oligarchy with considerable political and economic power; indeed, in a few cases merchant fullers became both mayors and masters. In the 1680s, we can identify 23 merchants fullers, of whom 15 were citizens inside the guild.Footnote 63 These are the individuals who may be classified as gentry within the guild in accordance with the 1671 Hearth Tax data (see Figure 2).

The social stratification of the Tuckers’ Company reflects its status as a site for the reconciliation of competing interests within the cloth-working sector and – more broadly – for the management of inequity and disharmony within the fabric of Exeter's urban life.Footnote 64 Hence, several of the wealthy merchant fullers entrusted their funds to the guild in the form of charity. Charity had always been a significant feature of guilds in the Middle Ages, but it was usually dispensed by the guild officers.Footnote 65 In the late seventeenth century, there was a proliferation of charity funds, and the Tuckers’ Company administered at least six.Footnote 66 Table 5 is based upon a charity founded by one of the merchant fullers, and it implies that about half of the guild's members were recipients of such funds. These recipients were both poor non-citizen guild members and also wealthy citizens inside the guild. Because as a rule guild members were not wage earners but traders,Footnote 67 these forms of charity were different from the poor relief provided by the city. Rather than providing handouts of money, the bequests administered by the guilds were generally loan schemes.Footnote 68

Table 5: Drake charity recipients (1640–90)

Sources: Rowe and Jackson, Exeter Freemen; Cresswell, First Minute Books; Cresswell, Minute Book 1618–1698.

Furthermore, the guild charities also benefited the middling sort of guild members, as well as the masters and parents of apprentices. For example, the merchant fuller Thomas Crispin – a strong nonconformist who was both a mayor and a guild master – established a charity in 1689 to provide five pounds every year for two poor boys (sons of tuckers or weavers) to be apprenticed for eight years in their fathers’ trades. After satisfactorily completing the apprenticeship, each was provided with a further five pounds to set them up in their trade.Footnote 69 In the course of 100 years this charity helped 200 boys to be bound as apprentices.Footnote 70 This amounts to nearly all freemen cloth-workers inside the guild who were admitted during the same period.Footnote 71 Thus, apprenticeship was clearly still influenced by the guild framework; however, this influence was not based on a trading monopoly. Rather, the guild controlled apprenticeship through premiums and funds to set up in a trade.

It could thus be said that voluntary charity rather than corporate monopoly forged the functioning of the guild in the late seventeenth century.Footnote 72 Although there were many types of charity bequests in late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Exeter, most of the charities in question were founded after the mid-seventeenth century (see Table 6), and many of the founders were merchant fullers who had become rich through exports to France.Footnote 73 The Restoration was a particularly crucial period for this growth in the guild's charitable function amid the decline of its monopoly.Footnote 74

Table 6: Establishment of charities

* According to Stephens, Seventeenth-century Exeter, 137–8, Drake was an exception because he was permitted to export to Spain only and not to the French company's monopoly area.

Source: Youings, Tuckers Hall Exeter, 137–40, 159.

In short, Exeter's merchant fullers controlled not only the city chamber but also the Tuckers’ Company during the late seventeenth century. However, their policies were sometimes contradictory; for instance, in order to increase the number of craftsmen it was necessary to keep wholesale prices lower. Certainly, they were able to control the guild and thus control the quality of cloth, but given its actual worth for the merchants in the late seventeenth century, the guild itself lost a great deal of power. It also lost its monopoly of traders, and royal support was declining. In this context, the institution of apprenticeship functioned to maintain the quality of cloth by charity association, a disciplining process which put apprentices under permanent scrutiny for the adequate expression of bourgeois self-management.Footnote 75

Conclusion: some historiographical implications

This article has examined the decline of craft guilds in early modern England via a case-study of Exeter's Company of Weavers, Tuckers and Shearmen, otherwise known as the Tuckers’ Company. It has been shown that although the guild's membership increased in the late seventeenth century, citizenship in Exeter increased even more rapidly, meaning that the proportion of citizens who belonged to the guild actually declined. More importantly, the Tuckers’ Company seems to have lost its monopoly over Exeter's cloth industry in the second half of the seventeenth century, as the proportion of fullers who were members of the guild declined from 84.6 per cent in the 1620s to 41.4 per cent in the 1690s. Yet both wealthy fullers and less wealthy cloth-workers continued to join the guild in the second half of the century. This trend is explicable by examining the charitable support offered to guild members, which seems to have been the primary motivation for joining the guild. Thus, the Tuckers’ Company in Exeter did not decline in the late seventeenth century, even though its monopoly did.

As the background of this transformation of guilds from bodies of monopoly to bodies of charity, two features of post-Civil War Exeter have been stressed here. One is the decline of royal power which had underpinned the guild in the early seventeenth century. The other is the shift of power in the guild from (craftsmen) fullers who supported its monopoly to merchant fullers who supported increasing the number of craftsmen in the city in order to decrease wholesale cloth prices.

The analysis presented here has a number of historiographical implications. First and foremost, it supports the ‘new orthodox chronology’ proposed by Epstein and assumed in recent discussions at least until around 2009, which brings guild decline forward into the eighteenth century. On the other hand, it does not support Walker's argument concerning guild control after the late seventeenth century, as the Tuckers’ Company lost control of apprenticeship due to the decline of its monopoly.Footnote 76 Despite this fact, the guild was still able to monitor contract compliance via premiums and the provision of funding to set up apprentices as independent traders, and to that extent it still administered skills transmission on the basis of the master–apprenticeship contract.

Thus, the case of Exeter confirms Epstein's emphasis on the critical technical role of early modern guilds in the absence of compulsory schooling and efficient bureaucracies. With regard to the controversy concerning the decline of guild regulation, the shift of power in the guild from craftsmen fullers to the merchant fullers in Exeter shows clearly how guild ‘weakness’ in Ogilvie's rather political sense goes hand-in-hand with continued ‘strength’ in Epstein's economic and technical sense.

On another note, it has recently been argued (contra Epstein) that English apprenticeship was much more diverse and flexible than previously thought, resembling training in some other parts of Europe (which normally involved shorter terms followed by several years as a journeyman).Footnote 77 The development of training by self-management in Exeter's charity apprenticeships confirms this new perspective.

In the context of comparative urban history, Exeter counts among those southern regional centres with 5,000 or more inhabitants whose growth rate far outstripped London and the northern manufacturing centres during the first half of the eighteenth century.Footnote 78 Why was this the case? On the whole, these southern towns were guildated, and it is well known that the main function of guilds shifted from trade regulation to charitable and education trust during the eighteenth century. Although craft companies often lost their vocational unity as the economic interests of their members diversified, they remained as wealthy social clubs lending prestige to an oligarchic elite.Footnote 79 Likewise, freedom of the city had often lost much of its economic justification by the late seventeenth century, as non-citizens increasingly evaded civic control.Footnote 80 While this may well have been the situation in many of the southern guildated towns, Exeter was rather different in some respects. As I have shown in this study, its transformation was more positive, as it managed to outcompete other English towns.

It is often remarked that, in comparison with the Continent, English provincial towns did not acquire a strong position because of the strength of the English government and the resulting reduced independence of English urban centres.Footnote 81 Nevertheless, from the mid-seventeenth century onwards, royal power was periodically challenged by town corporations.Footnote 82 As we have seen, by the late seventeenth century, the royal charter received by the Tuckers’ Company in 1620 had become ineffective.Footnote 83 In Exeter, a divorce between city freedom and trade has also been emphasized,Footnote 84 and certainly some freedom was admitted immediately prior to parliamentary election. However, merchant fullers preferred to increase the number of craftsmen fullers; they controlled the city chamber, and wished to maintain some relation between freedom and trade in order to increase the number of citizens outside the guild. This resulted in a decline of monopoly. Even if they were fully controlled by the merchant fullers, the guilds themselves were powerless without a monopoly and royal support. In this situation, the charity apprenticeship was the most appropriate means of maintaining the skill of cloth-workers – and in this case, too, voluntary association succeeded apprenticeship.Footnote 85

With regard to citizens outside the guild, Exeter's situation was not unique among regional English urban centres. York and Salisbury also had citizen cloth-workers outside the guild, and although York's merchant tailors and Salisbury's tailors survived, their monopoly had come to an end before the early eighteenth century.Footnote 86 Nevertheless, this situation was the exception rather than the rule. In the case of another regional urban centre – Gloucester – the municipal authorities had taken over the monopolistic enrolment of apprentices from the guilds by the end of the sixteenth century.Footnote 87 And although more than half the urban population lived in small towns, most of these did not possess functioning guilds by the mid-seventeenth century.Footnote 88 As for London, membership of a livery company was required in order to be granted the freedom of the city. Thus, these urban centres require separate attention, as they did not possess citizens outside the guild – the criterion which has formed the basis for this study.Footnote 89