In 1939, Attilio Romano, the secretary of the National Fascist Party's section in Rhodes, urged a stronger Italianization of local schools to foster support for his regime and the party's influence on education. In this colonial territory formerly part of the Ottoman Empire, he claimed the need for pre-military education at school and for extending access to the fascist party after graduation to local subjects. Although the colonial government did not implement this project, Romano voiced his party's wish to mold youth in “the crucible of faith of the Italian School,” an indispensable step toward the “light of Fascism” and the “ardent postulate of Italianità.” Romano's statement also explicitly attacked the influence of “Greek irredentism” and, in the regime's antisemitic vocabulary of the late 1930s, “Jewish-Masonic capitalism” on local youth.Footnote 1 Fascist colonialism in Rhodes on the eve of World War II struggled with legacies of the Ottoman past as it addressed the obstacles to its assimilatory mission.

Schools and students were not mere targets of Italian rule in Rhodes. Based on late Ottoman school infrastructure and its later transformation by fascist colonialism, male students elaborated original protests at school charged with a broader political meaning. They developed territorial visions and challenged the authorities by displaying alternative yet not always antagonist identifications with regard to fascism. As David Pomfret argued for the Southeast Asian context, colonialism produced a “crystallisation of new understandings of the social and political agency of ‘youth.’”Footnote 2 Young students in Rhodes acted not simply as “legitimate witnesses” of a post-Ottoman Mediterranean in flux, they contributed to shaping it.Footnote 3 Sarah Maza recently invited historians to highlight young persons’ agency not as a field in itself, but as a “point of entry into another issue,” namely to understand what “children make adults do.”Footnote 4 Indeed, school unrest in Rhodes mattered because changes in educational and governmental strategies originated as a response to their actions.

Romano's vision of fascist assimilation belongs to the last turn of Italy's rule in this corner of the Mediterranean before World War II. Almost thirty years earlier, in 1912, Italian troops had occupied Rhodes and other Aegean islands during the Italo-Ottoman War, a conflict in which the main targets were the North African territories of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. After a decade of military occupation, the Treaty of Lausanne (1923) recognized Italian sovereignty over a territory known as the Dodecanese. The negotiations at Lausanne prepared the death blow for the Ottoman Empire, but this also was the first international conference at which Benito Mussolini's government represented Italy, since his fascist party had seized power in October 1922. From an Ottoman provincial capital, Rhodes became the center of fascist Italy's Possedimento delle Isole Italiane dell'Egeo (Possession of the Italian Aegean Islands). The term possedimento designated an ambivalent entity in between a province and a colony of the Kingdom of Italy. This choice reflected the unique cultural, racial, and juridical position of the Dodecanese in the Italian imperialist metageography: too far and different to be assimilated with metropolitan Italy, too “white” and “civilized” to be compared to African colonies.Footnote 5

This position had concrete implications for how the local population would have to be socialized in educational institutions. Especially in the town of Rhodes, schools showcased the human and institutional diversity inherited from the Ottoman period.Footnote 6 Like many Ottoman towns, albeit in a remarkably balanced ratio, Rhodes hosted Muslims, Jews, and Orthodox, with a few dozen Catholic families. The town's demography stood out among other Dodecanese islands which, except for Kos, were almost exclusively inhabited by Greek-speaking Orthodox. Until the late 1930s, Rhodes preserved this diversity even in a period marked by the un-mixing of peoples in the Aegean, culminating in the exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey within the framework of the Lausanne treaty.Footnote 7 A 1922 census recorded 6,461 Muslim, 5,654 Orthodox, and 4,038 Jewish inhabitants.Footnote 8 Fourteen years later, another census based on citizenship also featured 4,081 Italian “nationals” residing in Rhodes, mostly settlers from the Kingdom of Italy or former residents of Anatolia holding Italian citizenship.Footnote 9

Beyond reflecting confessional diversity, schools, and especially secondary schools due to the higher cultural and social capital attached to them, were embedded in a changing political field. The first secondary schools had been founded during Ottoman rule, between 1883 and 1909. They were part of a dynamic provincial setting in which Ottoman state authorities, communal leaders, and foreign institutions concurred while expanding their visibility and influence. During the early years of Italian occupation, reforming these schools was not the priority of military governors. It was inconvenient to invest in infrastructure in the decade of warfare that redefined borders and polities throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and made the territorial future of the islands uncertain. This changed significantly after Lausanne. The first civil governor of the Dodecanese, Mario Lago (r. 1923–36), profoundly transformed local schools to consolidate Italian sovereignty. His strategy was based on two principles, applied to education and other domains as well: first, preserving Ottoman repertoires of governance based on religious difference by accommodating them to colonial rule; and second, hampering any foreign influence that might awake nationalist, anti-fascist, or anti-colonial sentiment among the population. In line with the evolution of the National Fascist Party and a tense international context, Lago's successor, Cesare Maria De Vecchi (r. 1936–40), championed a more aggressive style of governance. He introduced compulsory education until the age of eleven, reinforced the governor's direct control over schools, and imposed stricter criteria for personnel, administration, and curricula in non-state schools.Footnote 10 This was the context in which the fascist party claimed the need for assimilation in 1939.

In this article, I discuss Italian rule in Rhodes by decentering policies tackling an “education issue” and governors “experimenting” in a “laboratory,” frequent tropes used in histories of colonialism.Footnote 11 I place schools and students at the center of the narrative by examining their relationship with communal and state authorities. I argue that schools founded in Ottoman times, explored in the first section of this article, were a necessary precondition for the later politicization of male youth during the transformation from Ottoman to Italian rule. More specifically, unrest among students happened in two crucial moments during this transformation. In the 1910s, as my second section shows, school protests intersected with the end of Ottoman rule by addressing the Italian military occupation and the persisting uncertain sovereignties in the Aegean. In the third section, I move to the mid-1930s, when new protests gained ideological momentum as students positioned themselves in relation to fascism with statements and actions not tolerated by the authorities.

Students in Rhodes were not a cohesive group sharing durable visions. They acted ephemerally and in separate collectives of confessional belonging. Muslim students claimed a role as future leaders of their Ottoman fatherland during World War I, whereas Orthodox students called for the annexation of the Dodecanese by Greece during the Versailles peace negotiations.Footnote 12 More than a decade after the Ottoman demise and the stabilization of Italian sovereignty on the Dodecanese, in 1937, younger cohorts of Orthodox students from the same school claimed their Greekness and protested against fascist assimilation measures. Only one year earlier, their Jewish peers had advocated a synthesis of Zionism and fascism, which colonial authorities neither comprehended nor accepted. By including students of different confessions in a common narrative, the article highlights a general change in youth politicization illustrated by consideration of the 1910s and the 1930s. Whereas in the earlier period colonial authorities saw school protests as manipulated by elders and a mere refraction of communal fragmentation, in the 1930s they admitted that students acted autonomously in the name of nationalisms that were not compatible with fascist colonialism.

School protests and youth politicization are a protean phenomenon in modern history, but World War I was a key moment in this regard. Away from the battlefront, the educational, the ideological, and the military fields converged, sparking a fire that radicalized students and former students even after the end of the war. Despite a recent opening toward transnationalism in the history of youth, the nexus between education, war and post-wartime, and political mobilization still has a predominantly national frame. Historians have discussed a wide range of experiences related to state indoctrination and loyalty as well as resistance against the same.Footnote 13 Thus, Andrew Donson has shown how in the German Reich the hammering rhetoric of patriotic mobilization at school was effective, but later caused a polarization between pacifist socialism and an even harsher chauvinist right in 1917.Footnote 14 In the Ottoman context, Nazan Maksudyan has illustrated a general shift of education toward militarism and indoctrination at the war's outbreak, which affected (Turkish) Muslims and non-Muslims differently, leading to emotional support but also resistance.Footnote 15 After empires collapsed, as Dylan Baun has argued for interwar Mandate Lebanon, youth politics became an arena in which to mold the future nation.Footnote 16 In the post-Ottoman Mediterranean emerging from the war, national aspirations and imperial or colonial rule nourished recurring conflicts between authorities and students. Schools were a “touchstone for growing tensions,” as the anti-colonial revolts in British Cyprus in 1931 and the 1950s demonstrate.Footnote 17 The protests in Rhodes were part of this broader trend. They started with everyday interactions between students, teachers, and headmasters but escalated as these interactions also addressed broader political issues, becoming a concern for the authorities.

The politicization discussed in this article resulted from the specific Ottoman legacy of each school combined with transnational ideological stimuli arriving in Rhodes from its surrounding Mediterranean environment. Youth became politicized when students mobilized slogans, took explicit stances addressing the ruling authorities, and appropriated the school as a space of political action. Students interpreted the unmaking of Ottoman rule as it intersected with the Italian occupation and with traveling ideologies that shaped the post-Ottoman Mediterranean. Although their actions were local, they engaged with political references from Ottoman patriotism to Greek irredentism, from Revisionist Zionism to Italian fascism. This was amplified by the pivotal importance that all these political forces attached to youth, aimed at disciplining and co-opting it. Exploring the setting of Rhodes therefore also reveals how youth appropriated political references beyond their respective centers, and how a colonial power reacted to the activism of its subjects.

Educational policies and changes in school infrastructure affected both male and female students, yet a detailed account of how this affected the relationship between genders is beyond the scope of this article and deserves a separate study. The sources related to episodes of unrest taken as a focus here mention only male students. This is evidence that the evolving intersection of schooling and politics was not gender-neutral, as it produced a new, cross-confessional profile of masculine student youth active in the public space.

School protests also allow us to reconsider political transformations from Ottoman to colonial rule beyond histories limited to either period or focusing upon one single community. By assigning the leading voice to local subjects and valuing the diversity of their intents, fascist colonialism in the Aegean appears under a new light as post-Ottoman history. For one thing, Italian rule interpreted the legacy of Ottoman school infrastructure by preserving an imperial mindset based on governing loyal confessional communities. For another, this mindset was challenged by students who aspired to political horizons larger than domesticated communities. Yet, beyond legacies and visions, the basic precondition to addressing colonialism as post-Ottoman history on Rhodes is to delve deeper into the local infrastructure before the beginning of Italian occupation.

Education, Authority, and Politics in a Late Ottoman Province

Only marginally addressed by studies on Italian rule in the Dodecanese, secondary schools founded in Rhodes before 1912 constituted a late Ottoman educational field in flux. As elsewhere, the Ottoman state high school—mekteb-i idadi, often mentioned in the documents simply as idadiye—was divided into a lower (ruşdiye) and a higher (the proper idadiye) section. The Public Educational Bill (Maarif-i Umumiye Nizamnamesi) of 1869 had foreseen the foundation of an idadiye in every town with more than 1000 households, later reframed to include every province hosting an army headquarters.Footnote 18 In 1884, the idadiye of Rhodes was among the first of this kind opened outside the imperial capital. This development also resulted from earlier efforts by the Ottoman intellectual Ahmed Midhat Efendi, who had been exiled to Rhodes in the 1870s for his proximity to members of the reformist circle known as the “Young Ottomans.”Footnote 19 Unlike in other settings, the founding of the local idadiye was not a response to Western “encroachment,” since no rival secondary schools existed in Rhodes town before it.Footnote 20 Rather, this was a sign of the Ottoman state's plan to standardize the educational infrastructure of its provinces and of how intellectuals based in these provinces could accelerate such innovations. The idadiye of Rhodes had a prominent location towering over the walled town, next to the medieval palace that had hosted the Knights Hospitaller before the arrival of the Ottomans and the Suleymaniye Mosque, built immediately after the conquest of 1522. Benjamin Fortna has argued that most Ottoman high schools were located far from the city center, as the government claimed a “break with the past” by redefining the foci of the empire's urban space.Footnote 21 In Rhodes, quite exceptionally, the idadiye placed reformed state education in the heart of the town's glorious history. The school was a non-boarding institution hosting approximately 150 male pupils. They were mainly Muslims, with a yearly average of 15 percent Jews.Footnote 22 Tuition fees applied from the fourth grade onward, although in the last years of Ottoman rule more than half of the pupils were exempted.Footnote 23

Rigid discipline defined the relationship between the school authorities and the pupils at the idadiye. The attestations on discipline (tekdir ilanları) preserved in the Greek State Archives of Rhodes for the years 1905–8 inform us of the importance assigned by Sultan Abdulhamid's autocracy to morality at school.Footnote 24 The students started their curriculum with fifty credits for “morals” (ahlak); credits were deducted after every infraction recorded in their personal files.Footnote 25 These documents, which describe frequent bullying and carrying of weapons, also contain fragments of the pupils’ voices.Footnote 26 The “culprits” were asked to give their own accounts to investigating commissions of teachers, who collected notes through questions such as “Why did you run away [from school]?”; “Who was with you?”; and “Where did you walk around?”Footnote 27 Despite the asymmetry between them and the surveillance apparatus at school, students negotiated the reconstruction of events by adding their own versions. In this way, these male teenagers gathered first experiences as accountable individuals in front of disciplining authorities.

Most literature on Ottoman students focus on retrospective accounts by the elite and how schooling shaped future careers and political stances.Footnote 28 François Georgeon has argued that “questioning authority” along generational lines evolved into support for the Young Turk movement at the turn of the 20th century.Footnote 29 Although this assumption is relevant when discussing state politics from the center, there is scarce evidence that pupils in Rhodes were involved in the anti-authoritarian spirit that characterized students in larger Ottoman cities, especially in Istanbul. Nevertheless, a look at an Ottoman provincial town like Rhodes can reframe school life beyond a state-students relationship based on indoctrination and, as unintended results, “ideological bankruptcy” and organized dissent.Footnote 30 Documents like the tekdir ilanları show a densification of disciplinary interactions that allowed students to become more aware of local authorities. This was a necessary precondition to feeling entitled to link school management with broader political issues, as the example of the school unrest in 1915 will demonstrate.

In 1889, a few years after the idadiye had been founded, Henry Ducci, a local British Catholic subject, made a donation for the opening of a francophone missionary school. The French consul coordinated the efforts between his government, which provided a subvention, and the order of Frères des Écoles Chrétiennes (which would take charge of teaching).Footnote 31 The Frères boys school was the most confessionally diverse in Rhodes, and it was regarded as an elite institution.Footnote 32 For this reason, school authorities built a harmonious relationship with the Ottoman administration. According to the school chronicle, governmental inspections increased after the proclamation of the Ottoman Constitution in 1908, propagating attachment to the state in line with the Young Turk movement. In 1910, the provincial governor (vali), whose son attended the school, told the students to “learn your mother tongue, whatever it is, then your father tongue, that is Turkish, and finally French, the universal language of civilized countries.”Footnote 33 The acceptance of diversity coexisted with efforts to impose loyalty, an attitude that the Young Turks shared with the later Italian occupiers. As the Frères school director commented in 1912, the school was in a “quite delicate” position, since it could not “disown” the previous rulers who had “welcomed” it, nor the Italian “newcomers.” Hence, the personnel “kept complete neutrality, preventing pupils from any reference to politics [toute allusion politique].”Footnote 34 Unfortunately, there is no available firsthand account describing the students’ attitudes in those years. The school chronicle merely mentions that at the outbreak of the Balkan Wars “attention was more difficult to keep in class” as some students “dream[ed] of the old Byzantine Empire.”Footnote 35 This is an ironic hint at the Great Idea (Megali Idea), the vision of Greek expansionism in the Aegean which, since its origins in the early 19th century, had been directly linked to possible Ottoman territorial losses at the center of the “Eastern Question.” This form of irredentism was in fact rather dormant in Rhodes before the arrival of the Italians, but it would vehemently erupt a few years later, as will be shown below.

Another francophone school, run by the Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU), was the first in Rhodes to offer full curricula for both boys and girls. Founded in 1902, the school represented a break with religious Talmud Torah schools. Like the idadiye, it was established through the initiative of a prominent intellectual. Avram Galante, a Jewish journalist, scholar, and expert on educational reforms, was a convinced supporter of an Ottoman patriotism that transcended religious differences. He had spent some time as teacher at the Rhodes idadiye around the turn of the 20th century.Footnote 36 Galante's initiative to found a modern school was supported by local notables, foreign donors such as Baron Rothschild, and the Alliance headquarters in Paris, which provided for programs and administration while also contributing to personnel salaries. Throughout the Mediterranean, the Alliance's activities had produced different reactions within Jewish communities, with frictions emerging especially in settings in which other educational reformist projects competed with it.Footnote 37 Moreover, these frictions could have a generational dimension. In Salonica, where the first school had been founded in 1873, a conflict soon arose between the “rabbinical autocracy” and the “rebellious youth.” The latter staged acts of public disobedience against traditions such as shaving their beards and breaking the Shabbat to display support of the Alliance's modern education.Footnote 38 Contrary to such situations, in the first decade of its existence in Rhodes the Alliance school did not provoke significant communal strife.

Like the Frères school, the Alliance hosted regular visits by Ottoman authorities. In 1910, the provincial inspector of education exhorted the pupils to learn Turkish, which would open the possibility to “become deputies, governors or even ministers.”Footnote 39 This went hand in hand with stronger state interference, since the pupils were obliged to sing new Ottoman patriotic songs introduced during the early constitutional regime.Footnote 40 Attempts by the Young Turks to bring nationalism into the schools reinforced the visibility of politics, a contrast with the Hamidian period. During the Italian military occupation, governors remained eager to display their authority and replaced the Ottoman officials who visited the Alliance school. In turn, the French consulate's support for both the Alliance and the Frères schools was a buffer with which neither the Ottomans before 1912 nor the Italians during the decade of military occupation wished to clash. This explains the teachers and pupils’ neutrality not only vis-à-vis the changing authorities, but also concerning the state of war between the Italians and the Ottomans.

The last secondary school founded prior to the Italian occupation was the Gymnasium Venetokleion. Minos Venetoklis, a Rhodian who had made a fortune in Alexandria, was the main sponsor of the institution, which was named after him and administered by the Orthodox community.Footnote 41 The laying of the school's cornerstone in 1909 involved intellectuals such as the lawyer Giorgios Georgiadis, who frequently used the Greek term patrida (fatherland) in a speech contrasting the “dark era” of the past with an “enlightened” future awaiting the entire community.Footnote 42 A teleological interpretation linking education and patriotism as mere allegiance to Greek irredentism would be misleading.Footnote 43 The Greek-language newspaper Rodos (Rhodes, also founded in 1909) equally evoked patrida in discussing questions that linked the school management to the local Orthodox community and to broader Ottoman politics.Footnote 44 The Venetokleion thus provided students with an ambivalent notion of fatherland, which could be adapted to changing circumstances at the local and regional levels.

To sum up, the plural educational landscape in Rhodes reflected political tensions in Ottoman and Mediterranean politics. No school was purely local, and there was a coexistence of expatriate and foreign donors, Ottoman authorities and Western governments, and secular and religious institutions. These schools’ personnel circulated in a broader space of experiences and ideas. Whereas, in some cases, this corresponded to the proximity of different social, religious, and linguistic categories of students at school, it also could foster notions of belonging more exclusively linked to the state or to the intersection between communal and national belonging. Overall, in the years before 1912, students experienced an atmosphere unthinkable for their parents’ generation, in which Ottoman state authority but also outer references were increasingly tangible. The Italian occupation and the regional turmoil during the Ottoman twilight triggered student politicization, whose conditions of possibility lay in this precolonial history of educational polyphony in Rhodes.

Student Visions During World War I: Between the “Reins of the Fatherland” and a “Revolutionary Movement”

After the Treaty of Ouchy ended the Italo-Ottoman War in October 1912, the fate of the Aegean islands depended on the military operations that both countries were to carry out in accordance with their agreement. The treaty provided for Ottoman withdrawal from Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in exchange for Italian withdrawal from the islands, but the concomitant outbreak of the Balkan Wars and the resulting territorial uncertainties froze the treaty's implementation. Unstable sovereignties were a general feature of the region in those war years. Already in 1914, the British imposed a change of status of the Ottoman territories it had occupied in 1878 and 1882: Cyprus and Egypt became a colony and a protectorate, respectively. By contrast, the Dodecanese only underwent a shift from a “pawn occupation” (1912–15) to a proper “war occupation” after Italy declared war against the Ottoman Empire in August 1915.Footnote 45 Rhodes and its schools were outside the reach of significant operations during World War I. The absence of mass violence compared to other Aegean settings combined with nominal Ottoman sovereignty to hamper profound institutional transformations. Luca Pignataro has illustrated how military governors, exchanging views with ministers and experts, introduced classes in Italian at all school levels between 1912 and 1920.Footnote 46 This anticipated the foundation of proper “Italian schools” for both sexes in the early 1920s. Valerie McGuire pointed to the broader scopes that linked the management of education under military occupation with promoting Italy's image as an imperial and Mediterranean power rivaling Britain and France.Footnote 47 What is marginal in these accounts, however, is a perspective situating Italian governance next to concurrent visions emerging on the ground. If we frame Italian occupation as post-Ottoman history, namely against the backdrop of an Ottoman province in the whirlwind of the war, local students appear as mouthpieces of competing expectations.

February 1915 marked the beginning of the Gallipoli campaign, in which the Entente aimed at a breakthrough at the Dardanelles. The operation lasted nine months and ended with the Ottomans forcing the British and French troops to withdraw. The March issue of the Ottoman magazine Ceride-yi İlmiye (Scientific Journal) displayed a list of Rhodes-based donors of war aid (iane-yi harbiye) for the Ottoman army. The idadiye students “under the guidance (delaletiyle) of the vice-director of education Mehmet Kadri” collected the sum of 75.52 Fr, a substantial amount considering that, among those who donated in the French currency, only one wealthy notable surpassed it.Footnote 48 Such student initiatives were seen elsewhere in the empire, although the Italian occupation of Rhodes makes the notion of a “home front” problematic, since most of the students’ families were not involved in fighting. Moreover, behind this act of loyalty highlighted by the Ottoman press, the situation at the idadiye had been tense during the previous months.

The religious judge (qadi) of Rhodes, who was put in charge of educational matters by the Italian authorities after 1912, had fired one of the teachers, Ahmet Tevfik, who in turn accused a colleague named Kenan Efendi, of “pederasty.” When the school launched an internal investigation, Kenan responded by denying that any improper relations had occurred. Yet his account also reveals that proximity between teachers and students could occur outside school, and that this could easily be misinterpreted:

One day, I saw the seventh-grader, Ziya Efendi, son of Mehmet Ali Efendi, at the coffeehouse. . . . I invited him to come to my house to discuss the question of how to solve his difficulties [in finding the motivation not to drop out of school], together with Hassan Efendi [the chief janitor], who visits me in the evening. . . . Ziya came with the sixth-grader Mehmed Galip Efendi and . . . we told him to come in as a matter of courtesy. . . . A third evening Ziya again came with Mehmet, and after half an hour Mahir, son of Şevket, also [arrived]. . . . Not judging it appropriate to send them away, but in order to avoid these visits, Hassan and I decided to go to the market in the evening, and since then no [further] meetings have taken place.Footnote 49

Kenan asserted that his accuser, Ahmet Tevfik, had stirred the students against the school administration. He also claimed that the students “held meetings in coffeehouses and other gatherings to make propaganda” against him, referring to the suspicions of sexual encounters that had occurred some months earlier.Footnote 50

One day after Kenan signed this attestation, students from the fifth, sixth, and seventh grades submitted a complaint to the investigating commission regarding maladministration at school. They condemned the favoritism in the appointment of professors by the headmaster Mehmet Kadri (the war aid donation's organizer), whom they accused of embellishing his house with maps and furniture purchased with the school's budget. Nor was Kenan spared the students’ wrath. In their view, Kenan had been appointed as mathematics professor although he “had never studied it” and “he is well known as an immoral person.” The same reproach concerned the janitor Hassan who taught gymnastics although he “completely ignores the subject” and even tried to sexually abuse children when they were in his custody for detention punishment. Kenan and Hassan, who were additionally in charge of history and geography classes during the vacancy of qualified teachers, not only invited pupils home, but also “stalked them day and night until gossip reached the student body and the local population.” In general, the students denounced being treated like culprits because of their complaints instead of being regarded as victims of maladministration. Concluding with a flourish, they regretted that Rhodes “has lived under the enemy occupation for three years” and that the school mismanagement “has provoked in us, who will draw the future reins of the Fatherland, a sense of rebellion and hatred” (vatanın atı-yi mukadderatını idare idecek olan biz talebelerde bunlara karşı bir hiss-i isyan ve nefret uyandırmış).Footnote 51

Adult teachers likely played a role in this initiative. The students, however, addressed these issues as future leaders of the Ottoman body politic, which remained a masculine prerogative. Writing as peers aware of their rights and the older generation's duties, they pointed to the entanglement of masculine morality, discipline, and politics. These students openly confronted the school authorities, which punished them by awarding zero instead of eight credits for conduct at the end of the school year. The Italian authorities reexamined the case and interpreted it as a friction between local “Old Turks” and “Young Turks” competing for appointments within the community, since military occupation granted them more autonomy from Istanbul. The police claimed to be “not concerned” by these rivalries. Still, they suggested creating an Italian commission to restore the “regular functioning of the schools” and “the parents’ trust” to prevent problems for “public order and security.” State authority took advantage of this “necessity” to control schools through permanent supervision, also proposing mandatory Italian language classes in all local schools.Footnote 52 An episode of school unrest could thus reverberate on different levels, revealing factionalism within the community that, in turn, reflected political tensions within the Ottoman Empire. This contributed to linking the pupils’ activism to fears of negative consequences for public order among the Italian rulers, which in turn accelerated the latter's unmaking of Ottoman authority on the ground.

Shortly after the idadiye incident, in May 1916, Italian authorities banned on the island of Karpathos local Muslims who were alleged members of the Committee of Union and Progress. The military governor feared that allegiance to the ruling party in the Ottoman Empire might destabilize the Italian occupation, although nothing else is known about these Muslims’ political inclinations at a time when the Committee employed dictatorial repression and genocidal violence within the Ottoman Empire's borders.Footnote 53 More than ideology, the military occupation interpreted politics primarily in territorial terms. This is why, after the outbreak of the Balkan Wars, the Italian governors focused their attention on another menace, Greek irredentism. In fact, the demands for enosis, union with Greece, were not necessarily anti-Italian. Orthodox activists hoped that the occupation would end soon and promoted enosis to the authorities as the Italians’ benevolent duty.Footnote 54 After the Armistice of Mudros accelerated the end of the First World War in October 1918, the “Dodecanese question” reemerged. As the Allies negotiated in Versailles, Orthodox Dodecanesian intellectuals based in Europe wrote pamphlets and petitions demanding the recognition of Greek primacy and of self-determination for the islands.Footnote 55 Italian diplomats discussed with the Greek government the eventuality of ceding the Dodecanese (except for Rhodes) to Athens. The resulting Tittoni–Venizelos agreement, which also included the unrealistic condition of British withdrawal from Cyprus, was suspended and eventually renounced by Rome in 1922. The break in diplomatic experiments coincided with the Greek defeat at the hands of Mustafa Kemal's troops in Anatolia.Footnote 56 During this instability, the strategic value of the southern Aegean had been reinforced, and Italian withdrawal appeared as less likely. The islands even served as an outpost for Italy's occupation of southwestern Anatolia between 1919 and 1922.Footnote 57

Students in Rhodes did not remain idle during this period of instability and uncertainty regarding the island's future. In February 1919, unrest broke out at the Venetokleion. Giorgios Katsouris, a member of the communal educational institution called Eforia, complained that his son had been suspended from school “without a serious reason, only for a remark toward the gymnastic teacher.”Footnote 58 Supported by Bishop Apostolos, Katsouris pressured the Venetokleion's headmaster, who stood by the punishment. The headmaster paid a price for his inflexibility. He was summoned to the bishop's office, where he was dismissed from his position and even beaten up by Katsouris. Fearing that the situation could degenerate, the Italian authorities increased the presence of the Carabinieri (their colonial police) in town and ordered them to remain neutral.Footnote 59 Indeed, the situation escalated when students rallied at the headmaster's house in support of him, and then proceeded to the Greek consulate to voice their rage against Katsouris and Apostolos. Other students occupied the gymnasium until the negotiations at Eforia ended in their favor: Katsouris was dismissed from the council and the headmaster was reinstated.Footnote 60

The Italian police restrained from violence and observed that students shouted slogans supporting Italy. However, unrest at the gymnasium did not calm down. A few weeks later, a manifesto entitled “Resolution of the Greek Student-Youth of Rhodes” (Psifisma tis mathitiotis Ellinikis neotitos Rodou) was circulated in town. Writing “in the name of the Holy Trinity,” the signatories claimed that all “Greek Student-Youth” were paying close attention to the peace conference that would determine the future of the Dodecanese. They lamented the “obscure” (skoteia), “devious” (ipoula), and “sinister” (katachthonia) means by which the Italians sought to “change the very Hellenic spirit” (Ellinikotatou fronimatos) of the population. The resolution, drafted at the Venetokleion, was signed by twelve students of ages between sixteen and twenty.Footnote 61 Nonetheless, it was intended as a broader claim of a collectivity defined along ethnic (Greek), social (students), and age (youth) criteria:

1) [The Greek student-youth] has declared the union of the very Hellenic island of Rhodes with our sweetest Mother Greece.

2) It firmly declares that it will not accept any other solution with regard to the fate of the very Hellenic and glorious island of Rhodes, as well as the other eleven islands [currently] in the same condition of suffering.

3) It strongly protests against Italy's attitude as well as its unexpected and arrogant pretensions.

4) It declares that, in case of a condemnation sentence [leading to Italian sovereign annexation], it will lead the general revolutionary movement of the people that is being prepared spontaneously and resolutely, and that it will turn this beautiful island into ashes and ruins. . . .

5) It sends one last but very warm prayer that the ardent, centuries long, and rightful claims of the entire population of the Dodecanese be recognized and protected. . . .

On behalf of more than four hundred students,

The Delegates.Footnote 62

This resolution remained an ephemeral manifestation. Those involved did not display significant political activism in later years, although this also applies to many adult initiatives in the global aftermath of World War I. Also, the claim to represent all students was a clear case of hyperbole. The younger Katsouris, whose punishment had sparked the incident that galvanized the students only a few weeks earlier, also signed onto the list. Yet, despite the differing positions claimed at the Venetokleion, the school occupation and the resolution can be described as the first student unrest that shook the Orthodox community, which found itself in a particularly delicate position at this moment.

Like their peers at the idadiye, the Venetokleion students reacted to a disciplinary measure with their own interpretation of patriotism. The complaints about school maladministration and against notables resembled each other. However, as the geopolitical situation evolved between 1915 and 1919, school pupils adapted their demands to address regional politics and the war's victorious powers. Whereas the idadiye students emphasized their role as future leaders of the Ottoman fatherland, their Venetokleion counterparts first attacked communal authorities and then produced an echo of the Wilsonian moment, evoking a revolutionary movement. Some Muslim and Orthodox students were forcibly disappointed by the impossibility of an Ottoman return to Rhodes or by the missed chance of annexation by Greece. As the Ottoman political institutions were succumbing to the Allies’ partition plans and the rise of Mustafa Kemal's nationalist troops, Greece was still torn by the wartime schism between supporters of King Constantine and those of Prime Minister Venizelos. Yet the students in Rhodes made it clear to the Italian authorities that schools were not simply institutions to be administered through the bureaucracy. They were sites of confrontation from which challenges to colonial sovereignty might emerge through the resonance of regional politics. To avoid risks of disorder, the state had to surveil and penetrate schools. In this regard, fascist colonialism would adopt a strategy already initiated by the Young Turks. Assuring that schools praised the glory of Italy and fascism would be as essential for the former as praising the empire's territorial integrity and its constitution had been for the latter.

Of Badges and Berets: Student Engagement with Fascism

At the idadiye and the Venetokleion alike, the Italian authorities at first interpreted unrest as related to communal affairs. The elders allegedly instigated and manipulated the youth. Following the Treaty of Lausanne, Governor Lago viewed the reform of schools as a priority, to increase state control of these elders and, through them, of young colonial subjects. Although internationally recognized sovereignty assured this possibility, the governor was aware that changes had to be balanced with continuity to enhance his rule's stability. For instance, the Frères school kept its Catholic instructors, as the Alliance schools kept their Jewish teachers and as well remained under the administration of the Jewish community. However, Lago Italianized their personnel and programs. This was mostly aimed at challenging France, Italy's imperial rival in the post-Ottoman Mediterranean when it came to influence on Jewish and Catholic communities. By redefining the educational infrastructure in the Possedimento, the governor also aimed to determine the territory's place within the Italian imperial space. Schools in Rhodes arguably reflected a lesser degree of structural racism than Italy's African colonies, yet this did not erase the difference between metropolitan and indigenous categories.Footnote 63 The 1925 local school reform underlined the freedom assigned to confessional communities to develop programs and appoint teachers. A new institution, the Superintendence of Public Education (Sovraintendenza alla Pubblica Istruzione), would verify that all diplomas were issued through an exam at the new Italian Royal School (Regio Istituto), that Italian was taught in all schools, but also that Greek and Turkish were taught at the Italian secondary schools.Footnote 64 Moreover, although girls already had access to secondary education at communal schools, Lago institutionalized female education as a branch of the Regio Istituto, where instruction was assured to be by a mix of religious and civil teachers.Footnote 65

The reform also exploited the relative tranquility of Aegean geopolitics in the mid-1920s. Greece was still recovering from the shock of its Anatolian catastrophe, and the newborn republican Turkey navigated a phase of political fragility. In this sense, the “autonomy” assigned to the Orthodox and the Muslim communities aimed to sever their ties with foreign governments and donors at a favorable moment. Nevertheless, the youth moving abroad for secondary and even higher education and then returning to Rhodes remained a thorn in Lago's side. Although he could not totally prevent this mobility, establishing that an Italian state exam was necessary to attain some of the most remunerative and prestigious professions was another means of discouraging youth from pursuing their education abroad. Given the Italian authorities’ perception that local Muslims generally had a more favorable stance toward Italian rule on the Aegean islands, the Muslim community's school was not considered as dangerous as the Orthodox gymnasium. Still, in the early 1930s Lago's anxiety about student mobility led him to pressure Muslim communal leaders. They were to dissuade Muslim families from sending their children to Turkey, where they would have been exposed to a Kemalist politicization not compatible with fascist colonialism.Footnote 66 In sum, Lago's reform did not simply recreate or erase the Ottoman multilayered educational landscape. Rather, it was an ambivalent claim of preserving communal autonomy with a conciliatory attitude of noninterference with local notables. At the same time, it was a precondition to transforming and domesticating these communities, to bring them under Lago's control and away from extraterritorial influence.

Within this double dynamic, the governor faced the question of how to integrate the colonial population into Italian institutions, including the National Fascist Party. He emphasized that Italy's goals in the Dodecanese could not be achieved overnight. In 1929, answering a query about the Dodecanesians’ right to become members of Mussolini's party—inaccessible to adult colonial subjects without full citizenship—Lago deemed the time unripe and invoked a future “new generation” of “good fascists” breaking with the “amorphous” past and the “secret pride of race and religion” which characterized the confessionally fragmented population.Footnote 67 Youth, the pendant of this new generation, would validate fascist colonialism's transformative power. This strategy undoubtedly marked the mindset of many youth, although schools remained exposed to the circulation of alternative identifications. This is observable in two episodes of unrest in the mid-1930s related to the Jewish schools and the Venetokleion.

As colonial rule was concerned about foreign influence in Rhodes, it did not anticipate that politicization could emerge through contacts with metropolitan Italy itself. In the mid-1930s, a network of Italian Jewish teachers and intellectuals propagated Vladimir Jabotinsky's Revisionist Zionism. One of them, Renato Coen, had spent some months in Rhodes at the Jewish school, and a dozen Rhodian students visited cities like Milan where this circle was particularly active. This circulation of ideas between the colony and the metropolis changed the way the Jewish youth in Rhodes perceived their place within the fascist empire.

But what were the motives behind Revisionist Zionism's appeal in a fascist colonial setting like Rhodes? Since the late 1920s, Jabotinsky had flirted with Mussolini. Italy's support was instrumental to pressuring the British administration of Mandate Palestine, which Jabotinsky contested (hence “revisionist”), arguing for a Jewish nation–state. Moreover, Jabotinsky was fascinated by fascism's political mobilization and state doctrine, especially corporatism as an antidote to class struggle. The cult of youth was a key point of convergence, as Jabotinsky aimed to create loyal disciples for the Zionists’ future state. Thus, in 1934, a naval academy in Civitavecchia, near Rome, opened under the auspices of the Revisionists’ youth organization, Betar.Footnote 68 This proximity allowed Revisionist Zionism to be considered less insidious than foreign nationalism or even communism, at least at first sight.

Jabotinsky was aware that a group of Revisionists existed in Rhodes in late 1935.Footnote 69 Sympathy for previous currents of Zionism had emerged there in the aftermath of World War I but remained quite minimal. Compared to other (post-)Ottoman settings like Istanbul and Salonica, the community of Rhodes was not as polarized between partisans and opponents of Zionism in general.Footnote 70 However, the birth of a Revisionist faction took the Jewish elders and the Italian police by surprise. In 1936, the community's president Hizkia Franco attempted to address the Revisionist youth in a column for the local Ladino newspaper, El Boletin (The Bulletin). The police confiscated the article just before its publication to avoid a further fissure in the community. Franco had stated that:

This propaganda is directed by inexpert youth, who do not seek party members among mature and developed men, capable of assuming responsibility for their opinions, but among the neighborhood's youth, a prey likely to fall into the movement's net. They have nothing better to do than extend the movement among our school's pupils, whose lips still smell of their mother's milk.Footnote 71

This political agitation was described as only pertinent to youth, both as propagators and receptors. The leaders had already graduated, but several of their followers were still students at the local Jewish school. As early as November 1935, Mario Levi, the headmaster, sent Hizkia Franco a worried letter. He described third-grade students’ reluctance after his “invitation” to restrain from wearing the Betar badge (distintivo) at school. All but two of them protested by writing on the blackboard that “the whole third grade is Betar.” Levi claimed that he exerted “energetic efforts” toward “keeping the pupils away from political struggles” that “excite their minds with visions of things that they certainly are not ripe enough to comprehend.” Unfortunately, he stressed, these students resisted his pressure based on “obedience” to their older fellow Revisionists. The younger ones, however, were not just passive recipients. One of them stood up in class and shouted: “This is not politics! It is fascism!”; another stated that “Revisionism is like fascism, it is even fascism itself,” echoing Jabotinsky's followers in Rome.Footnote 72 The students justified their interpretation of fascism based on writings of intellectuals living in Italy who had a sound relationship with the regime. What worried the authorities was not the students’ ideas, but their politicization tout court. It was seen as a mimicry of fascism, an excess of meaning and voluntary activism trespassing the limits accorded to colonial subjects.

Informed by Franco, the police seemed clueless about the relationship between Revisionism and fascism and asked their counterparts in Milan, Rome, and Florence for further information.Footnote 73 The authorities opted for an “admonition” of the fourteen youngsters identified as the leaders, but the movement did not fade out.Footnote 74 A few months later, one Revisionist argued with an Italian citizen and instructor of the youth section of the fascist party, to which colonial subjects had access until twenty-one years of age. The instructor scolded him, claiming that “fascism and Revisionism are not compatible and that he had to choose between belonging to the Italian or the Jewish party [sic].” Two former pupils of the Jewish schools contacted the National Fascist Party secretary and the head of the police with a detailed complaint. They reiterated the bonds between Jabotinsky and Mussolini and highlighted the sincere fascist attitude of many Italian Revisionists. They stressed that “Revisionism and fascism not only identify with each other in their ideology in general, but also in essential and precise elements in their political, social, and economic domain.”Footnote 75 These debates revealed a complicated relationship between the Italian authorities and the community's president, Hizkia Franco. In June 1936, he was replaced by John Menashe, who immediately confiscated Betar badges and “goodheartedly” (bonariamente) repeated the admonition to discontinue activism.Footnote 76 Although badges continued to appear in the following days, the students’ activism eventually died out over the course of that summer. In the end, although the students’ agitation did not have serious consequences for what Italian rule considered public security, it highlighted the boundaries this rule posed to youth initiatives. Some Revisionists might well have changed their attitude when they abandoned their activism. Their leaders, however, did not comply with the authorities’ repression. Like many coreligionists, they chose to emigrate to Congo to find a better life prospect. As late as April 1938, a few months before Italy introduced the infamous racial laws institutionalizing state anti-Semitism, the police in Rhodes got wind that Moise Roscio, one of the Revisionist leaders, continued his propaganda in the Belgian colony.Footnote 77 Although no further information on his case is available from Italian sources, the persistence of this type of activism further complicates the picture of the relationship between fascist Italy, which had growing interests in central Africa after the invasion of Ethiopia, and the Rhodian Jewish communities in Congo and British Rhodesia. Although Anne Morelli has touched upon this issue as it related to loyalty to fascism and belonging as Italians, some of these Rhodian emigrants, especially the younger ones, elaborated their own political repertoire by looking beyond the one provided from above by Mussolini's regime (Fig. 1).Footnote 78

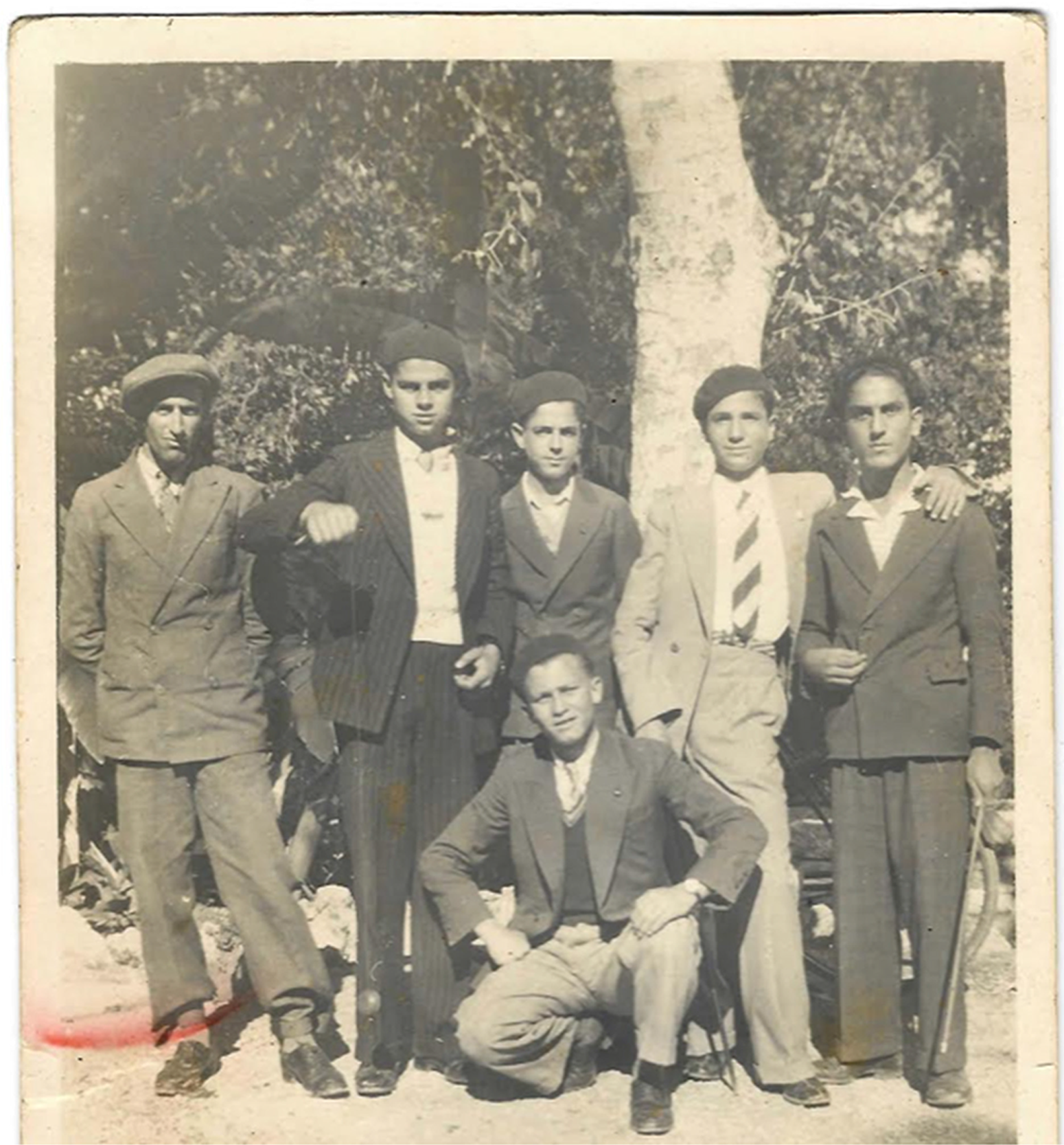

Figure 1. A group of Jewish students from Rhodes, 1935 or 1936. The second from the left is Elie Levi, who was among the leaders of the Revisionist Zionist movement in 1935–36. The dark berets that four of them wear most likely relate to the Betar youth organization, although no badge is visible in the picture. Like Moise Roscio, Elie Levi left Rhodes for the Belgian Congo in 1936. Photo courtesy of Benjamin Levy.

The movement's disappearance coincided with Lago's departure from Rhodes. The memoirs of historians and witnesses alike consider his successor, De Vecchi, to have had a profoundly different character and mark his replacement of Lago as a turning point for Italian rule in the Dodecanese. De Vecchi had been among the earliest and most radical fascists, one of the four quadrumviri who led the March on Rome in 1922.Footnote 79 He surely had other views on colonial politics than Lago, who was an experienced diplomat. As Valerie McGuire argues, these two characters were complementary within a rule perceived by locals at times as Italian (i.e., modernizing and culturally affine), at times as fascist (i.e., oppressive and foreign).Footnote 80 Indeed, any rigid contraposition between the two marginalizes continuities in ruling and surveillance structures, as well as responses to bottom-up initiatives. A case of student unrest at the Venetokleion just a few months after De Vecchi replaced Lago reveals the persisting duress of colonial rule when facing youth politicization.

Within the Orthodox community, threats against the bishop Apostolos had continued after the school protest of 1919. Supporters of Greek nationalism considered him pro-Italian for his ambivalence vis-à-vis Lago's unrealized project of establishing an autocephalous Dodecanesian Orthodox church and breaking the clergy's bonds with the patriarchate of Constantinople.Footnote 81 The Italian authorities also were suspicious of Apostolos due to his influence on the priests of minor villages and islands. Between November 1934 and January 1935, anonymous leaflets against him and the Venetokleion's headmaster appeared in Rhodes, and the police arrested a sixteen-year-old who confessed “his hatred against the metropolitan bishop.” They considered it unlikely that the youngster had acted on his own and suspected manipulation by the youth's father, a Greek citizen whom they labeled as “absolutely against” Italian rule. The youth stated that he had acted with a partner who denied any outer influence. The two confessed to sending this anonymous message to the school principal:

Mr. Headmaster, traitor of Greece, I hope that you will not spend the holidays here and that you and your damn boss [probably Apostolos] will leave. But you will see what will happen to you if you do not leave quickly!Footnote 82

Greece, allegedly “betrayed” by the headmaster, was undergoing political turmoil in 1936. On 4 August, General Ioannis Metaxas established a dictatorship in Athens that drew heavily from Italian fascism, including a massive effort to mobilize youth. In his first two years after seizing power, Metaxas underlined his friendly attitude toward Mussolini and avoided questioning Italy's legitimacy in the Dodecanese despite pressure from irredentist circles in Athens.Footnote 83 The dictatorship did not significantly influence Orthodox students in Rhodes. Their references to Greece were elaborated locally as well as through contacts with the Dodecanesian diaspora, especially in Egypt. Even more than the Venetoklis family mentioned earlier, the Kazoullis family maintained kinship, economic, and political bonds between Rhodes and Alexandria. Italian authorities were concerned about the Kazoullis's irredentist propaganda. The Alexandrian newspaper Dodekanisos, close to this family, claimed an anti-fascist and anti-colonial position but also avoided references to Metaxas's dictatorial nationalism.Footnote 84

These local and transnational motives fostered the Orthodox youth's politicization in the spring of 1937. Shortly after his arrival, De Vecchi had banned the berets worn by Venetokleion students, which were considered a politicized symbol like the Betar badges. The police reported in condescending language “scenes of fanaticism” with pupils “weeping and kissing” the berets when they gave them up.Footnote 85 These berets were a symbol of the school and, equally, of a masculine collective of peers. The authorities made no explicit links with Greece, although they might have feared the students’ identification with Metaxas's powerful National Youth Association (Ethniki Organosis Neolaias), the uniform of which featured blue berets for its members.Footnote 86 In the weeks preceding this ban, some members of the Orthodox community described by the police as “intellectuals” who were “soaked in irredentism” were anxious about De Vecchi's “penetration” in school affairs. The likely impossibility of receiving donations from abroad, most notably from Dodecanesians in Egypt, raised their doubts about the gymnasium's economic survival.Footnote 87 The tension culminated a few days later, as the headmaster announced that, like their peers of other confessions and schools, all students would attend the fascist celebration of the Foundation of Rome (Natale di Roma) on 21 April. One student aged eighteen stood up and declared that he and his classmates would not take part in the ceremony and would instead go on strike. He also criticized the school principal by saying: “Mr. Headmaster, did you not always tell us that we are Greeks?”Footnote 88 Seeing no possibility to negotiate with the school authorities about this obligation, all fifth- and sixth-graders joined the strike and even “threatened the younger ones” should they not follow. The police admitted that the strike involved “the large majority of the students” and the Possedimento's director of education reported that “[The possibility of] any external or parental interference in the students’ rebellious determination should be excluded, and such determination must have obtained a strong approval among some of the pupils.”Footnote 89

Although no local newspaper mentioned the strike, De Vecchi was furious and had the headmaster dismissed, seven pupils (briefly) arrested, and the three “leaders” among them expelled from all schools of the Dodecanese.Footnote 90 Although police sources do not refer to calls for enosis, this protest directly challenged fascist colonialism. It was an overt act of resistance against the National Fascist Party's increased control over local society in the 1930s. The students’ malaise moved from anonymity to public actions precisely when the government accelerated its fascistization and Italianization. Under this pressure, the notion of patrida circulating at school since its foundation in 1909 became an anti-colonial identification. The authorities lashed back and pressured the new school board to have the pupils join the youth sections of the party. Despite such pressure, only seven of them did so, and the whole school was shut down that summer and reopened only in 1943.Footnote 91 As mentioned above, the Fascist Party responded by urging military education and access to the party for colonial subjects two years later. Yet, under these circumstances, fascism would have bitten off more than it could chew.

Conclusion: Schools as a Dilemma for Fascist Colonialism

The outbreak of the Second World War further hampered any solution of the struggle between fascistized assimilation and the maintenance of colonial hierarchization. As late as 1944, seven years after the Venetokleion incident, Rhodes was governed by what remained of the local Italian administration. The rulers were loyal to the fascist Italian Social Republic, which depended on German military occupation in the north of the country; the Allies had started liberation of the south. This was an exception, as most territories of the Italian Empire had already slipped away from fascism's control following the first defeats in Africa. Italian civil servants in Rhodes acted jointly with their allied German military occupiers, who had landed in September 1943 to secure the strategic outpost in the Aegean.Footnote 92 Soon afterward, war violence reached its apex with the deportation of the Jewish community in July 1944. Yet, there also were signs of local resistance. The brother of one suspended Venetokleion student, Michalis Vrouchos, was arrested and shot for being active in a secret organization operating in the British army's mission Erratic, aimed at destabilizing Italian rule during the war.Footnote 93 He is to this day celebrated as a martyr, together with his comrade Giorgios Kostaridis. It would be tempting to interpret the politicization at Rhodian schools as a linear trajectory of anti-colonial sentiments leading to the demise of Italian rule and the enosis of 1948, after two years of British military administration. However, the Revisionist movement at the Jewish schools reminds us that diverse attitudes toward fascist colonialism could emerge.

When considering together different episodes of school unrest, we can reconsider the temporal and spatial coordinates of colonial rule, beyond a relationship between state and society considered in terms of oppression and resistance or modernization and support. The twenty-two years between the declaration of patriotism by the idadiye students and the Venetokleion strike mark a period in the history of Rhodes in which teenagers engaged directly with ruling authorities. This was a cross-confessional phenomenon during war and peacetime, involving Ottoman state schools and communal schools alike, a profoundly Italianized school like the Scuole Ebraiche, as well as one that stood out for its continuity with Ottoman times like the Venetokleion. Through varying motives and actions, youth politicization reflected questions involving ruling authorities and communal notables related to the integration of a diverse population into state structures and the pressure of state-sponsored ideologies.

School pupils were an inflammable force that conflated these heated issues. They targeted the local reality of school and community management, the relationship with the ruling state, and questions of international politics. Their agency in those crucial decades reminds us that Rhodes remained permeable to the broader Mediterranean politics where ideologies, identifications, and visions circulated. This went against what late Ottoman and, even more, Italian authorities wished for, and what state-centered histories of colonialism tend to assume. After the Italians occupied Rhodes, a preexisting plurality of references—the state, the community, foreign powers, the nation, the fatherland—could be articulated as expressions of attachment to the Ottoman state, demands of enosis with Greece, and even sympathy for Italy and fascism in the name of Zionism. By turning the spotlight on schools and handing the podium to students, it is possible to retrieve microcosms of imperial and colonial pasts that go beyond the idea that governors’ educational policies determined the perimeter of the students’ socialization. The latter's experiences and initiatives at school shaped those policies, posing challenges and stimuli that the rulers attempted to counter. By re-centering the transformation of rule at its encounter with youth, the episodes of unrest described in this article become more than minuscule social movements evaporating at the school gates. They reveal polyphonic intersections between youth and politics as a factor in the transformation of imperial rule in the early-20th-century Mediterranean.