Introduction

The origins and development of national financial systems have attracted much attention since Gerschenkron’s seminal papers.Footnote 1 Recently, the debate has emphasized the influence of politics and interest groups on the development of financial systems.Footnote 2 A special case of this relation between governments and financial systems is state banking, when governments directly intervene in the allocation of credit through state banks that finance their needs by issuing state guaranteed bonds.Footnote 3 This article investigates the link between the formation of small-firm interest groups and the emergence of state banks geared toward small firms in the Netherlands during the early twentieth century. In particular, it analyzes how Dutch small businessmen succeeded in only seventeen years (1902–1919) to organize themselves sufficiently to obtain extensive government support for their needs, and how this resulted in state banking.Footnote 4

State banking first appeared in the nineteenth century in many European countries and reached an apex in the 1960s.Footnote 5 There were, however, large differences between countries in terms of state intervention and timing. Generalizing from empirical observations, Verdier put forward a novel thesis to explain the historical trend and cross-country variation. He claims that “state banking was the unintended child of class politics,” and argues this in three points.Footnote 6 First, state banking was demanded by sectors that were pressed to invest but did not have access to long-term credit because of the marginal importance of small and local banks in centralized states. Second, the emergence of class cleavage made these groups politically relevant, giving them the power to extract state banking from central governments. Third, the decrease in state banking is conversely linked to the fading of class cleavage.Footnote 7 Verdier also identified three waves of state banking. The first one took place between 1850 and 1900 and targeted farmers.Footnote 8 The second wave came after World War I and was geared toward small firms thought to suffer from a “MacMillan gap.” The third wave took place after World War II and focused on financing (large) industry while keeping inflation under control.Footnote 9

Verdier draws a causal link from small-firm lobbying to the emergence of state banks during the second wave, but the story is not that straightforward. This article presents an in-depth analysis of the Dutch case, which reveals that it was neither obvious or necessary that lobby groups of small entrepreneurs, termed middenstanders in Dutch, would successfully form and instantly exercise large political influence, nor that they wanted to obtain state banking. This highly diverse group was divided by social status, economic activity, and religious affiliation, and had to go through a difficult process of group formation and institutional entrepreneurship to gain political relevance. The ultimate success of this process was all the more remarkable because Olsonian collective action theory posits that large social groups are hard to organize and keep together.Footnote 10 Prospective members need persuading to donate time and resources to uncertain outcomes; interests are always varied, sometimes conflicting, threatening to pull organizations apart; and success distances leaders from membership, rendering it hard to keep free-riders away. In this case, leaders united members around a fictional common identity and common concerns, notably the lack of small- and medium-size enterprise (SME) credit, which they then used to obtain political support.

While collective action theory makes general predictions, Lemercier argued that scholars should also pay attention to local power constellations, varying windows of opportunity, and available organizational repertoires.Footnote 11 This is in line with the literature on the petite bourgeoisie as a social group, especially pushed forward by Crossick, Haupt, Jaumain, Kurgan-Van Hentenryk, Nord, Zdatny, Bechhofer, Elliot, and Kocka, who each analyzed the associational processes of small entrepreneurs in Belgium, Germany, France, or Austria.Footnote 12 Crossick and Haupt were interested “in the ways in which the political activity and ideas of European petits bourgeois took shape within a framework of constraints” made up by the state and the political forces.Footnote 13 And Peter Heyrman, who researched Belgian small entrepreneurs, chronicled the process of translation from socio-economic grievances into political action.Footnote 14 However, this literature was inattentive to credit or financial system development. The influence of culture and religion, documented in various contexts but ignored by Verdier, deserve more attention when researching group formation, lobbying, and financial system development.Footnote 15 Colvin showed the way here, arguing that one cannot detach financial development from social, cultural, and political contexts.Footnote 16

This article connects the Dutch case to the international historiography on social movements and state banking, a dimension lacking in the historiography. The most comprehensive work on Dutch middenstanders is an unpublished thesis by Van Driel that examined the socio-economic position of small entrepreneurs between 1880 and 1940, and how they tried to better their position.Footnote 17 Work by Pompe, van den Tillaart, and van Uxem focuses on describing the group of small entrepreneurs between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and the context they operated in during the afterwar period.Footnote 18 More recently, Dankers and Bouwens touched on these associations in the framework of wider business interest associations.Footnote 19 One particular aspect of the Dutch case, SME credit institutions, received ample attention from Colvin.Footnote 20 This article adds to his work by showing how those banks were part and parcel of a process of group formation.

The period under research starts in 1900, right before the founding of the first national middenstander association, and ends in 1927 with the creation of the NMB (Nederlandsche Middenstandsbank, Dutch Middenstandsbank), which Verdier identified as the start of Dutch state banking.Footnote 21 The main focus is on the period up to 1920, with a short excursion to discuss the 1921 financial crisis and its aftermath.Footnote 22

The article is organized as follows. I first sketch the social and economic backgrounds to European middenstander movements in the second section, then the emergence of the Dutch movement and the formation of a common identity in the third section. The fourth section discusses the Dutch political and social landscape and the consequences of verzuiling, or pillarization, on the middenstander movement. This is followed by an analysis of how the movement gained political influence in the fifth section. The sixth section provides a brief overview of the developments during the financial crisis of the 1920s and the founding of the NMB. The final section concludes.

The Rise of Middle-Class Movements in Europe

The history of the Dutch middenstander movement in many ways runs parallel to the experiences in other European countries. The push for middenstander associations in the late nineteenth century was often sudden, but not accidental.Footnote 23 The Long Depression (1873–1896) decreased agricultural prices, which impoverished farmers and farming villages. This pushed many jobless farmers into self-employment (often into shopkeeping) to make an income.Footnote 24 At the same time, the belief in free markets and competition made countries remove entry barriers for many crafts and trades.Footnote 25 As a result, the retail sector and many low-skilled crafts became overcrowded.Footnote 26 Between 1870 and 1895, there were enough customers for everyone due to the rising purchasing power of urban workers. Then, real wage growth stagnated in France, Germany, Austria, and Belgium, and turned negative in the United Kingdom, prompting shopkeepers’ associations to arise.Footnote 27 Shopkeepers took the lead, with small industrial entrepreneurs and craftsmen joining later.Footnote 28

In fact, those associations formed the response to wider social and economic movements and emerging class cleavage. Big business developed, growing in size, influence, and number of employees. Labor started organizing itself all over Europe, demanding better working conditions, and threatening to upset the status quo. Labor movements set up purchasing cooperatives to cut out middlemen and provide cheaper goods to members. Small craftsmen and shopkeepers feared getting squeezed between capital and labor following Marx’s prediction that there would be no place for SMEs in a world divided into the haves and have-nots of capital.Footnote 29 In practical terms small shopkeepers felt their livelihoods were under threat from large, vertically integrated corporations with economies of scale, on the one hand, and from workers’ consumer cooperatives, on the other hand.Footnote 30 At the same time, a political void opened. The rise of workers’ movements and trade unions made liberal political parties, previously champions of middle classes, shift toward large capitalists. In response, industrial and commercial middling groups all over Western Europe, known variously as petite bourgeoisie, classes moyennes, Mittelstand, or middenstand, formed their own associations.Footnote 31

Forging a Common Identity

The start of the Dutch middenstander movement is usually placed in 1902, with the founding of the Nederlandsche Bond van Vereenigingen van den Handeldrijvende en Industriëele Middenstand (NBVHIM, Dutch Federation of Associations of the Trading and Industrial Middling Class). The federation modeled itself on middling class associations abroad and those of farmers and laborers at home.Footnote 32

The pioneers of Dutch middenstander associations noticed that in neighboring countries, especially Belgium and Germany, successful national small-firm lobby groups had developed that gained support of their local and national governments.Footnote 33 Several Dutch entrepreneurs attended conferences abroad about middenstand topics and invited foreign speakers to the Netherlands, resulting in knowledge networks between them. For example, in 1902, Belgian professor and head of a study group for the petite bourgeoisie, Oscar Pyfferoen, wrote an extensive report about the situation of the Dutch middenstand and compared it to Belgium.Footnote 34 The following year, these international collaborations were formalized in the International Institute for the Middenstand.Footnote 35

At home, labor unions, which were active since the late 1860s, had representatives in Parliament starting in 1897. Under pressure from increased competition and falling profits, farmers had successfully turned to the self-help solution: setting up unions to represent their interests.Footnote 36 In 1898 farmers gained official recognition when the government set up a department of agriculture within the Ministry of Internal Affairs.Footnote 37 The Dutch government was thus integrating interest groups into the formal state structures and decision-making processes. This set a precedent to continue on the same trajectory with the novel middenstander movement, if only because a widening of the franchise in 1896 turned lower-middle classes into voters.Footnote 38

According to Crossick and Haupt, a government’s decision whether or not to insert the petite bourgeoisie into cohesive structures shaped the associational structure of the movement.Footnote 39 Pressure-group activities by national associations was much more common in countries where efforts were made to incorporate the middenstanders into the political constellation (e.g., Belgium, France, and Germany).Footnote 40 The same process can be observed in the Netherlands, where national associations arose to facilitate contact with the government and lobby for integration into the state. One can expect that pre-World War II state banking arose not only in centralized countries, as Verdier predicts, but also where national SME lobby groups took hold, such as in France, Germany, and Belgium. The United Kingdom was very centralized but lacked a shopkeeper or SME movement, and state banking was practically nonexistent.Footnote 41

In the Netherlands, national middenstander associations became more common after 1900, when parties and politicians tried to attract support from the middenstanders.Footnote 42 Most interest came from the side of the confessional parties, for whom middenstanders formed a natural target audience. Just like politicians on the left captured the growing discontent of laborers, confessional parties did the same with the middenstanders. There was an ideological readiness, or “poisedness,” to support the middenstanders.Footnote 43 The confessional parties believed strongly in the “antithesis theory” propagated by the prominent neo-Calvinist theologian and charismatic politician Abraham Kuyper, and tasked themselves with “moralizing society” and ensuring the protection of Christian values.Footnote 44 The goal was to maintain or reinstate the “God-given order” in society by preserving the middle classes and preventing class warfare. Furthermore, confessional thought promoted the idea of “sovereignty in spheres,” meaning that every sphere of life (economy, family, profession, etc.) should rule itself and was not subjugated to other spheres.Footnote 45

According to Verdier, class cleavage increased the importance of small firms, which then made themselves relevant by playing the part. The movement presented itself as a positive force, a social core representing admirable values such as independence, diligence, and moderation, which were stabilizing against class war.Footnote 46 Middenstand professions were seen as aspirational for members of the laboring classes. If they worked hard and saved well, they might be able to start their own businesses.

The societal importance of the middenstand was raised in parliamentary debates during the early 1900s.Footnote 47 Dutch government officials and members of Parliament attended international middenstander conferences in Belgium in 1900 and 1901. In 1901 Kuyper, then prime minister, addressed the international conference. Unsurprisingly, he praised the middenstand for starting to organize itself. However, he stopped short of promising support, saying no more than that the “government should decide whether something could be done to aid them” once the movement had become strong enough.Footnote 48

Building strength required finding ways of mobilizing an undefined and undefinable group of business people with distinct activities and interests. To achieve collective action, a joint social identity needed to be created.Footnote 49 Dutch middenstanders, like petite bourgeoisie in other European countries, were essentially a rather amorphous social-economic group wedged between the clearly defined groups of workers, on the one hand, and farmers, the free professions, and capitalist entrepreneurs, on the other hand.Footnote 50 They ranged from small mom-and-pop shops via artisans employing a few people and small manufacturers to department store and retail chain owners at the top. The demarcation between them was often paper-thin and fuzzy; even middenstanders themselves struggled to define their group.Footnote 51 Most attempts simply shut out the smallest businesses by proposing an economic threshold such as a minimum capital of 5,000 guilders, or the status of independent entrepreneur as a demarcation from paid workers.Footnote 52 Others gave much looser definitions, such as “those between small and large enterprises,” or anyone who was neither a wage-dependent worker nor a capitalist but rather people uniting capital and labor in their work.Footnote 53 In practice, this meant shopkeepers and master artisans but not farmers working their own land. Farmers had different economic interests and had their own associations that in turn excluded artisans and shopkeepers.Footnote 54

Dutch middenstander movements sidestepped the difficulty of defining their target group by opting for subjective categorizations, such as “those who feel they belong to the middenstand.”Footnote 55 That made joining a personal choice based on a desire to belong, and opened membership to anyone who self-identified as such. Such wide categorizations had the signal advantages of inclusiveness and power to unite, but the disadvantage of creating memberships with very heterogeneous interests and wants, an aspect often noted in the literature about European middenstanders movements.Footnote 56

Though the terms middenstand, petite bourgeoisie, and Mittelstand to denote a particular social-economic group already came into use during the late eighteenth century, they gained wider currency only around 1900.Footnote 57 This is underlined by the fact that the first Dutch middenstander organizations of the 1880s called themselves by different names. Some focused on shopkeepers and called themselves trade associations, such as the Delftsche Handelsvereeniging (Delft Trade Association, founded in 1884). They tended to concentrate on local problems such as unfair competition from peddlers, fire-sales, or a local cooperative store. The first national organization for middenstanders, the Bond voor het Maatschappelijk Belang (Union for the Societal Interest, 1885), was also a shopkeepers’ association with a single goal: fighting consumer cooperatives.Footnote 58 The NBVHIM, founded in 1902, was the first nationwide association with a broader set of goals and middenstand in its name. To better reflect the heterogeneity of its target group, in 1905 it added the term Industrial to its name to broaden its scope.Footnote 59

The impetus for association came from two distinct directions. A small group of wealthy and/or big city shopkeepers, feeling threatened by new social and economic forces, strove to unite middenstanders bottom-up to help them maintain or even improve their situation.Footnote 60 And Catholic priests, inspired by the Pope Leo XIII’s bull Rerum Novarum (1891), set out to form Catholic organizations top-down with the goal to limit capitalism’s excesses by creating or reinforcing social bonds.Footnote 61

The most vocal priests came from the south of the Netherlands and favored organizing Catholics along lines of class (stand) rather than profession (vak).Footnote 62 One of these priests, the influential and highly respected Dr. J. Nouwens, came from a middenstander family himself.Footnote 63 He considered association imperative, not necessarily because small retailers and craftsmen were doing so much worse than before but as a means to prepare for the time when they would be under attack by “the organized forces of capital and socialism.”Footnote 64 Nouwens was encouraged to do so by two influential priests, Herman Schaepman and Gerlacus van den Elsen. Schaepman was the leader of the political Catholic Party and member of Parliament, whereas van den Elsen spearheaded the Catholic Boerenbond (Farmers’ Union) movement and strongly believed that shopkeepers should also be united under the Church banner.Footnote 65 In 1902 Nouwens cofounded a Middenstand Federation. Nouwens actively consulted van den Elsen about his experience with the Boerenbond, and it was van den Elsen who suggested the moniker Hanze for Catholic middenstand associations.Footnote 66 That term harked back to an idealized medieval past and an economy organized in crafts and guilds under firm Catholic Church supervision. Another Catholic politician closely involved with the middenstanders movement was P. J. M. Aalberse, the son of a confectioner-baker.Footnote 67

Pillarization

The support for small enterprise by Catholic parties was not particular to the Netherlands. It also happened in Belgium, France, and Germany where the petite bourgeoisie was “discovered” as a force to stabilize a society thought to be dangerously polarizing.Footnote 68 Nonetheless, the extremely close involvement of people like Nouwens and Aalberse with the Dutch middenstanders movement highlights a peculiarity of Dutch society at the time: verzuiling (pillarization).Footnote 69 Different social groups formed parallel organizations of particular social groups along religious or ideological lines: Catholic, Protestant, liberal, and socialist. As a result, people could theoretically live their lives within a single pillar providing all necessary services such as schools, trade unions, political representation, newspapers, insurance, leisure, and even finance.Footnote 70 The Catholic pillar was the largest and most extensive, followed by the Protestant and socialist ones, whereas the liberal pillar remained relatively underdeveloped.

The middenstanders had to take into account this specific political setup of the Netherlands. Pillarization provided an obstacle to forming a strong and united middenstander organization. Already in 1892 some Protestant middenstanders had set up the Boaz Patroonsvereeniging (Boaz Employers’ Association), a national organization with local branches. Boaz was a hybrid organization that strove to provide a compromise between capital and labor by uniting employers, middenstanders, and laborers through their common Protestant faith. Led by large industrialists and claiming to promote the interests of middenstanders, Boaz actually focused on big firms, not on its majority membership of small middenstanders. As a result, the organization remained small at around three thousand members nationally.Footnote 71

The Catholics also started associating during the early 1890s. Leo associations were set up to further the interests of Catholic citizens, and included a large number of middenstanders.Footnote 72 Leo associations were closer to the middenstand and organized hierarchically in the Church’s effort to combat socialism. In April 1902, shopkeepers, together with the clergy, set up a proper Catholic Middenstands Union in Den Bosch.Footnote 73 Other Catholic middenstanders soon followed its example across the southern and central Netherlands, as a rule recognizable from having Hanze in their name. As often as not, it was the high clergy who took the initiative to set up associations.Footnote 74 Local ones started by middenstanders themselves still needed formal recognition from the Church to be accepted as Catholic.

Liberal associations emerged bottom-up and in response to local issues. They proclaimed to be open to anyone, including the politically and religiously neutral, convinced that the ideological separation of society diluted the group’s forces. Dual membership of general and confessional organizations did occur occasionally. Socialist middenstander associations did not form since Socialists believed the middenstand to be doomed anyway.Footnote 75

Pillarization handicapped the formation of large associations and caused a duplication of functions at the local level. The variously denominated associations had similar agendas and used similar tools but rarely collaborated. The Catholic Church only allowed interdenominational collaboration if Catholic organizations were insufficiently strong on their own.Footnote 76 As local organizations grew, cooperation decreased. As a result, a single town would have multiple insurance schemes, information offices, debt-recovery offices, and evening classes, one for each pillar and often in direct competition with each other. In a later stage, banks were also set up along ideological lines, with the Catholic Hanzebanks, neutral Middenstandsbanks, and the Protestant Boazbanks.Footnote 77

However, at the national level middenstand leaders did find ways to collaborate across pillars. They drew their inspiration from two international conferences for the petite bourgeoisie in Antwerp (1900) and in Namur (1901). J. S. Meuwsen, an Amsterdam hat-and-cap shop owner and president of the local neutral Algemeene Winkeliers Vereeniging (AWV, General Shopkeepers’ Association) took the initiative to organize a third conference in Amsterdam (1902) and obtained the support of Aalberse and the Protestant politician J. Th. de Visser to get it off the ground.Footnote 78 Prime Minister Kuyper was invited for a second time to address the conference. This time, however, he promised government support if the middenstanders took action and organized themselves.Footnote 79 This promise was important for the young movement. At the closing of the conference, Dutch middenstand leaders of all denominations did just that, launching the NBVHIM and electing Meuwsen as its first president.Footnote 80 Aalberse and de Visser joined the association’s advisory board.

The NBVHIM aimed to transcend pillarization and to provide one apolitical national umbrella organization for middenstander associations of all stripes. The NBVHIM claimed to be apolitical and have “only an economic, societal goal,” but that did not prevent it from welcoming the support of the confessional parties, which gave the NBVHIM legitimacy and access to political and financial resources.Footnote 81 Similarly, the Belgian Catholic politician Julien Koch stated during the Amsterdam conference that politicians were keen on making use of the associations for their own gains.Footnote 82

Unity under the NBVHIM did not last very long. In 1911, the Catholic associations broke away over a policy dispute and an alleged lack of respect, to form a Federation for Catholic Associations, the Nederlandsch Roomsch Katholieke Middenstandsbond (NRKMB, Dutch Roman Catholic Middling Class Union).Footnote 83 Six years later, Boaz left the NBVHIM and the Protestant middenstand section split from the Boaz association to form the Christelijke Middenstandsvereeniging (CMV, Christian Middling Class Association).Footnote 84 The NBVHIM continued its neutral and liberal course alone.Footnote 85 As I show, this fragmentation at the top along denominational lines did not hamper the middenstander movement’s ability to obtain government support for its initiatives and requests. The federations kept in close touch, shared initiatives, attended each other’s conferences, and referred to each other’s viewpoints in their respective trade journals, although not always favorably.Footnote 86 Separation of forces on the local level had more to do with control over the membership, as the leaders were aware that cooperation on the national level was necessary to reach their shared goals.

Belgium, Austria, and parts of Germany experienced something similar to pillarization.Footnote 87 But the two main competing pillars were Catholic and Social-Democrat, with the liberal pillar being limited to certain cities. Given the lack of support from the Social-Democrats, this means that the Catholic pillar, and to a lesser extent the liberal pillar, absorbed the middenstander movements in those countries.Footnote 88 This resulted in less competition within the movement and less duplication of functions compared to the Netherlands, which also had a Protestant pillar.

Mobilizing Members and the Government

Besides forging a social identity, the leaders of the middenstand needed to find ways to mobilize potential members and engage the government, all within the existing political constellation. The founding figures had little or no political experience, and public action representing their social group was fairly novel for them. Moreover, they encountered problems in attracting members and complained that middenstanders were difficult to unite because they failed to understand the commonality of their problems.Footnote 89 Conversely, middenstanders needed persuading that membership was worth their while, much like collective action theory predicts.Footnote 90 The only way to engage members was by offering benefits that would incentivize them to join and contribute to public goods such as political lobbying.

Motivations for joining associations differed from those for joining federations. Bennett showed that whereas members of associations want access to services and find collective representation to be of secondary importance, members of federations focus more on obtaining representation and lobbying.Footnote 91 There is a similar distinction in the Netherlands. Local associations focused on providing services for their members. Federations of associations (unions) also provided services but focused more on representation and collective action.Footnote 92 They aimed to organize and coordinate large club goods, such as banking infrastructure or large (interregional) mutual insurance funds, and to lobby the national government for subsidies and support.Footnote 93 Unions also thought about how to stimulate local membership since the size of the association determined its membership fee to the union.

Verdier sees state banking as a logical result of the rising political power of small firms, which would demand state banking to increase their access to credit. The historical example of the Netherlands tells a different story. Initially, there were various themes to rally support around and convince potential members to join associations, and for associations to join a federation. Insufficient access to credit, not demand for state banking, was one of them, and not even the most important one at first. It gradually became a focal point of the movement, eventually leading to state banking, although this was not the original goal.

Credit was discussed on fourteen different occasions at the annual national middenstander conferences of the NBVHIM between 1899 and 1920, only third behind topics related to unfair competition (forty-six times) and organization of the movement (twenty-nine times). The majority of discussions about unfair competition was concentrated between 1899 and 1907 (thirty-six times), after which it became less current.Footnote 94 Furthermore, unfair competition was splintered into various subtopics, which were discussed only a few times each. However, credit was discussed from the start. The 1902 conference, for example, singled out purchasing cooperatives and concentration of capital as the main culprits of the middenstand crisis and defined two policy goals to combat them: strong associations and better credit facilities.Footnote 95 The first NBVHIM agenda adopted these issues and solutions almost verbatim and without much discussion from previous conference agendas, adding only a desire to improve vocational training.Footnote 96 From there, credit became more dominant over time.

The increasing relevance of credit is telling. Credit was a concern shared by all middenstanders, so it could function as a mobilizing force. Other topics such as cooperative movements, taxation, unfair competition, and trade education lacked the unifying potential of credit because they were not shared by all subgroups to the same degree, or were simply impossible to achieve without external help.

Opposition to consumer cooperatives had been a reason for shopkeepers to associate in the Union for the Societal Interest in the late nineteenth century, but it fell apart due to lack of achievements.Footnote 97 By 1900 most competitive pressure on small shops came from upcoming retail chains and department stores, not consumer cooperatives.Footnote 98 Moreover, some middenstanders became pro-cooperative. Nonetheless, Protestant and Catholic groups remained divided on cooperation and cooperatives, and could not decide whether it was a just means of organization.Footnote 99 The situation continued until after World War II, with the exception of cooperative banking, which was embraced early on.Footnote 100 Even in neutral circles, purchasing coops were not a success. Contrary to consumer cooperatives, they were limited to one business line at the time and could only mobilize subgroups, often within a city or region. An overview of active middenstander cooperatives in 1912 lists forty-one cooperative banks but only twenty purchasing cooperatives.Footnote 101

Unfair competition was the most discussed topic in this period, which definitely had unifying power, but it lost relevance over time because it was splintered into various problems all with different contexts and possible solutions. Furthermore, combating competition from fire-sales or peddlers often required legislation that was beyond the associations’ reach when local governments did not cooperate. Taxation had also spurred several associations, but these were mostly local and concerned specific fees and taxes rather than the general income or corporate taxes (from which noncorporations were exempt) levied on the national level.Footnote 102 The Dutch associations were quite effective in organizing vocational education through evening classes, training programs, and lectures, and successfully obtained government support, but they found their members less than enthusiastic to participate.Footnote 103

Poor credit facilities, by contrast, were a common problem for small firms, at least if one believes the middenstanders.Footnote 104 Sales credit forced shopkeepers to tie up capital in customer accounts. This was a societally useful function helping customers to smooth consumption, but slow repayments and demands from suppliers to repay at ever shorter notice made shopkeepers vulnerable to cashflow problems.Footnote 105 Artisans found themselves facing similar bottlenecks, plus having to find capital for investing in newly developed equipment such as electrical tools.Footnote 106 The 1902 Amsterdam conference emphasized that small firms had no access to affordable credit on fair terms.Footnote 107 Both groups of middenstanders struggled with the key problem of being unable to offer collateral in a form acceptable to banks. Small firms rarely possessed the bills, promissory notes, or premises that bigger ones used to obtain bank credit. At the same time, the credit unions that had provided credit to small firms since the 1850s shifted to more lucrative, higher market segments.Footnote 108 The successful cooperative banks set up by farmers’ unions excluded middenstanders from their credit facilities in 1903.Footnote 109

Whether there was a real credit problem is less relevant than contemporaries’ belief that there was. Heyrman argued that in the Belgian case “it was not so much the real economic problems with which middenstanders had to deal that seem to have determined the political objectives of the middle-class movement, but the ways in which the organizations perceived the problems and rephrased them in their political programs.”Footnote 110 Dutch middenstanders similarly translated the problem of credit into a useful narrative to mobilize members and the government.

On the one hand, a lack of reliable information prevented government support, since it was unclear where to start. On the other hand, despite calls for a survey of the middenstand in 1902 and the creation of a parliamentary commission to investigate the middenstand in 1904, the government refused to organize a survey. Footnote 111 The associations also grappled with the lack of information, but they used it to their advantage. During the first national middenstand conference in 1903, they set up a commission to examine the problem of credit and make recommendations.Footnote 112 The commission devoted most effort to investigating whether specialized credit institutions for small firms should be set up (the answer was yes), and how they should function. There was not much attention as to why credit should be provided and even less to whom.Footnote 113 The lack of precision was in part due to an absence of data.Footnote 114 However, it was also convenient to the associations since different types of firms with different needs all felt their grievances were being addressed. Anyone, from the expansionist businessperson to the struggling entrepreneur, could imagine the plans being geared toward them. In this early period, credit was thus an effective way to convince a diverse membership that the associations were tackling their problems and working toward a solution.

Furthermore, incentives put in place by the government contributed to making credit central to the movement. Kuyper’s 1902 promise clearly urged the middenstanders to take initiative, and only then would the government come to their aid. In response, the associations paradoxically searched for options that were attainable without government support in order to obtain government support. Credit was one of these, since it was possible to start banks without any government help, yet easily fundable should the government decide to step in. Middenstanders originally did not ask for subsidies, and argued they could organize without external help. However, they knew it was possible to receive financial support because they referred to multiple examples from the first wave of state banking. German farmers and Mittelstanders, for instance, managed to obtain government support for their cooperative banks, and the Dutch government was already subsidizing the farmers’ cooperative banking system before 1902.Footnote 115

The case of the Hanzebanks illustrates how credit became a clear-cut and practical issue for the government to support. In 1902 the AWV successfully founded a cooperative SME bank, demonstrating that it was feasible without external help. Following this, and having studied the cooperative farmers’ banks, Catholic associations decided in 1904 to start a bank specially geared toward middenstanders, recognizably named the Hanzebank.Footnote 116 Members were to fund the bank by buying shares, with owning at least one share being a prerequisite for using the credit facilities. However, the expected swift uptake of the shares failed to materialize. By the end of 1905, only a third of the total had been placed, so the bank’s start was postponed and discussions began about lowering its capitalization.Footnote 117 In 1907, with the project in jeopardy for lack of support, the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade stepped in and approved a subsidy of 4,000 guilders.Footnote 118 That provided the necessary catalyst; a new campaign was set up to place the remaining shares, and in a few months’ time the majority was sold.Footnote 119

The subsidy did not signal a change in the position of the Liberal cabinet but was the result of the newly forged personal connection between the middenstand leaders and the bureaucracy. In 1906 J. C. A. Everwijn became the head of the Department of Trade of the newly formed Ministry of Agriculture, Industry, and Trade under J. D. Veegens.Footnote 120 Everwijn was closely involved with the founding of the Bossche Hanzebank in 1907 and several other Hanzebanks in 1909–1910. He earned Nouwens’s gratitude and developed a close friendship with Nouwens, whom he respected greatly.Footnote 121 Everwijn continued in his function until 1921 and became increasingly influential within the ministry.Footnote 122 He remained a contact point between the government and middenstander organizations.Footnote 123 The latter also remained stable in terms of leadership, offices, and activities. After twenty-five years, the NBVHIM (including successors) only had three directors and five secretaries.Footnote 124 This allowed them to build up knowledge networks and foster personal ties.

These new relationships and the entirely confessional Heemskerk government taking office in 1908 boosted the state’s interest and support for the middenstand. The same year, the government decided to organize the survey that the State Commission for the Middenstand had asked for in 1905.Footnote 125 At the same time, subsidies were made more broadly available.

To better capture these funds and increase their influence, middenstander associations improved cooperation between them and played the card of credit.Footnote 126 Credit was portrayed as having economic and educational benefits in helping small firms overcome problems and teaching them how to “properly run a business.”Footnote 127 The NBVHIM managed to obtain subsidies from Syb Talma (Protestant), the minister of agriculture, industry, and trade, thanks to the intermediation of Everwijn. They received 2,000 guilders to organize an exhibition (500 guilders) and provide information about the developing SME banking system (1,500 guilders) that Talma and his predecessor subsidized.Footnote 128 In 1909 Talma gave a short speech at the NBVHIM’s annual conference, which that year was dedicated entirely to credit. He stated that the government supported middenstand credit and that its support would continue to expand if the middenstand kept improving its organization.Footnote 129 This was no lie, and in 1910 a specific advisor for small firms, named Rijksnijverheidsconsulent (State Industry Consultant) was appointed.Footnote 130 Going further, in 1911 Talma appointed a Commission to Inform the Middenstand, which gave lectures on various topics concerning the middenstand, among others credit, payments, and credit cooperatives.Footnote 131 Simultaneously, the associations promoted the new credit options for their members. The Hanze of Haarlem, for example, published regular updates on the activities of their bank, tips on how to obtain credit, and a series of thirty-two-episodes on bookkeeping that was also referred to by their banking institution.Footnote 132

The increase in subsidies stimulated the founding of credit institutions. The number of banks increased from 3 in 1905 to 12 in 1910, and there were 59 banks operating a total 133 offices in 1914.Footnote 133 The membership followed; however, it was difficult to maintain cohesion in the diverse group, even within pillars. Small middenstanders complained their interests were not properly represented by wealthier, larger middenstanders who were out of touch with the struggles of the movement’s majority.Footnote 134 The leaders also became more paternalistic and criticized incapable fortune-seekers and unviable small firms that contributed to overcrowding in the retail sector.Footnote 135 Additionally, the industry consultants largely focused on medium-size firms and pushed for mechanization and increasing scale of operations.Footnote 136 This fault line persisted, and the Catholic pillar had open debates about the position of small middenstanders in the organization and whether the Hanze was useful for them.Footnote 137 Obviously, leaders of the Catholic associations argued it was.

The friction within pillars was partially due to the exclusion of the smallest middenstanders from the new banking system. In the early period, the banking system was very locally oriented and provided relatively small loans. Most banks’ statutes allowed loans between 50 and 3,000 guilders and appeared to stay in that segment.Footnote 138 In 1912 the average outstanding loan across middenstandsbanks was 755 guilders, almost the average household income at that time (848 guilders). The variance between banks was large, with many banks giving smaller loans on average of around 200 guilders, and others, such as Hoorn and Utrecht, giving on average of around 2,000 guilders.Footnote 139 Nonetheless, the poorer subsets were still often excluded from these banks because they were not credit-worthy or their firms were not viable, but sometimes because banks limited the amount of new loans due to capital constraints.Footnote 140

World War I was a catalyst for governmental support and the real starting point of the second wave of state banking in the Netherlands. The mass mobilization of soldiers, the scarcity of goods, and the maximum prices imposed by the Liberal cabinet of Cort van der Linden (1913–1918) heavily impacted the middenstand. On top of that, the war disrupted traditional trading credit lines as suppliers demanded cash payment for deliveries, causing cashflow problems for many craftsmen and shopkeepers.Footnote 141 The new banking system was insufficient to deal with the shock. In direct response to the crisis, Minister of Finance M. W. F. Treub helped Bos and Meuwsen to set up a Central Middenstandsbank in 1914 to provide liquidity to the SME banking system.Footnote 142 The government guaranteed 1 million guilders of national bank lending to the newly formed bank, making it a state bank.Footnote 143 The second wave of state banking started to save the private middenstandsbanking system, not because middenstanders planned to extract it.

Nonetheless, the direct effects of the state bank were small as it took a while before the Central Middenstandsbank was properly operating. While the government took measures, in 1915 Queen Wilhelmina urged Treub to do more, particularly for the smallest middenstanders.Footnote 144 By then, civil servants and the government fully recognized credit as a core problem, and they acted subsequently by increasing the budget for subsidies eightfold. The nominal value stayed roughly the same after 1916, but the high inflation eroded the real value quickly (Fig. 1). Nonetheless, the subsidy was more than enough to cover the operating costs of the Central Middenstandsbank and to subsidize other banks.Footnote 145

Figure 1 Yearly budget for Middenstandsbank-subsidy by the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry, and Trade, 1907–1920.

Source: Janzen, Het Middenstandsbankwezen in Nederland, 148.

To help small firms, the government subsidized a set of regional Adviesbureaux (Offices of Advice), which provided inexpensive or free financial advice. Additionally, several experiments in private-public cooperation took place, where local middenstand associations set up institutions for small-firm credit that were subsidized by national and local governments.Footnote 146 Following the queen’s intervention, Treub set up a Commission for Middenstands Credit in 1915 to help small firms get advances from participating middenstandsbanks by screening them and guaranteeing 55 percent of the default risk.Footnote 147 The commission helped 1,412 firms in this way and guaranteed 1.2 million guilders.Footnote 148

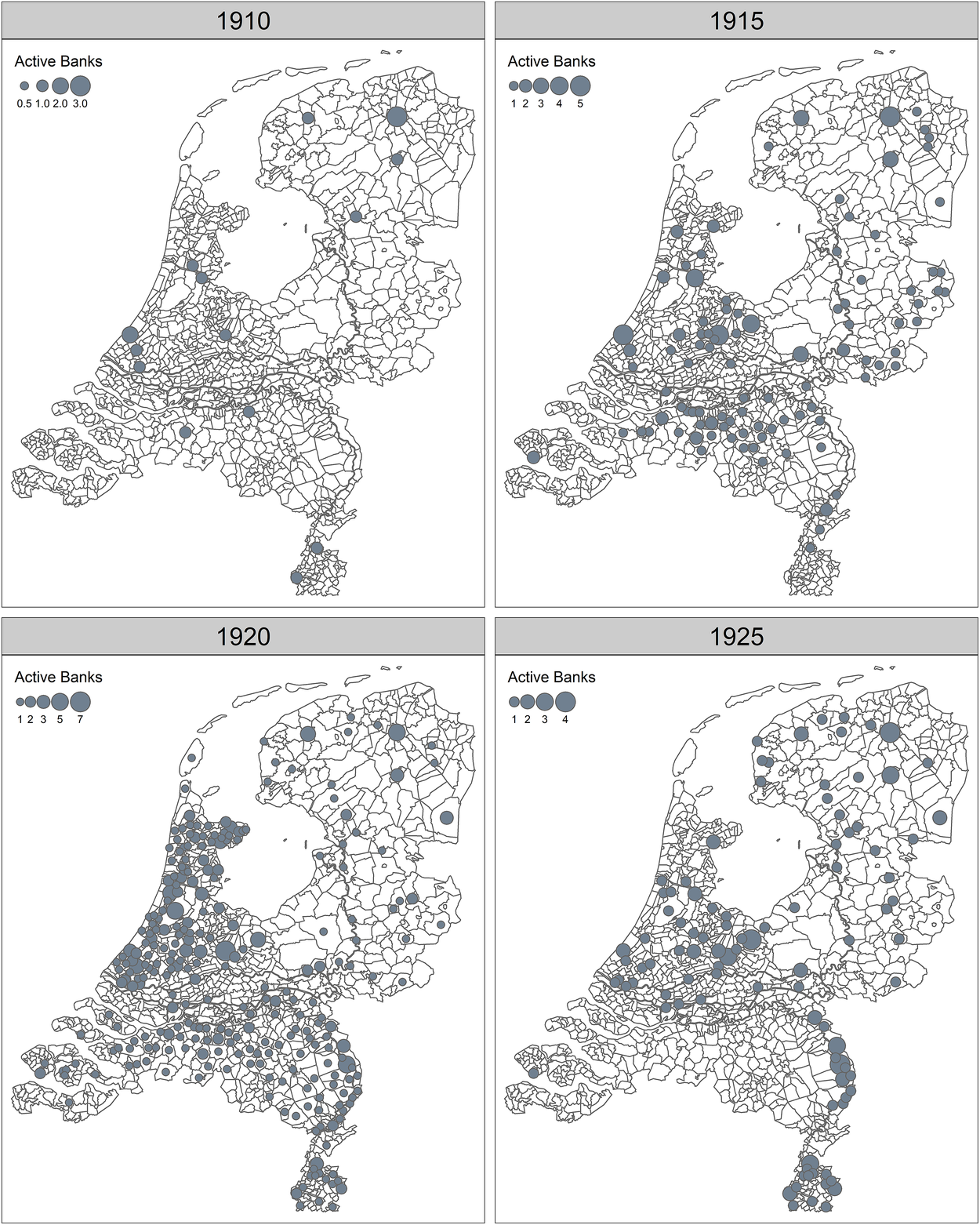

By the end of World War I, the middenstanders had put their problems, and credit in particular, firmly on the government’s agenda. As a result, they obtained extensive support for developing a separate small-firm credit system. Accordingly, the number of middenstandsbanks (including branches and correspondences) grew from 67 in 1915 to 95 in 1918. Including branches, the banks had 305 offices in 1918.Footnote 149 (fig. 2)

Figure 2 Number of active middenstandsbanks and branches, 1910–1925.

Source: UU Financial History Group, Banking Landscape Database, mapped on Boonstra, NLGIS Shapefiles. DANS, 2007, https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xb9-t677.

The apparent success of the new financial system raised the prestige of the associations and increased their appeal to (potential) members. The Catholic Hanze of Haarlem stated that the rapid growth in members (from five hundred to nearly three thousand members between 1910 and 1912) was thanks to their quickly expanding Hanzebank.Footnote 150 Their membership peaked around 1920 with close to ten thousand members, and fell after their bank went bankrupt in 1923.Footnote 151

The middenstanders received ample support during the war, but the government also made decisions against middenstand interests, which left them with some resentment.Footnote 152 In an attempt to strengthen their grasp on politics, the NBVHIM put forward the Groninger Motion in 1917. The motion was the middenstanders’ way to make sure that their interests were represented on the various party lists. The idea was that “politics should be kept outside of the middenstander movement, but that the middenstand’s interests should be brought into politics.”Footnote 153 The NBVHIM proposed to formulate a political program that would be sent to the main political parties, and asked the parties to put suggested candidates on their lists and to support their candidacies.Footnote 154

It was a response not only to the frustrations of World War I but also to the changes in the electoral system. First, earlier that year, the Liberal faction, aided by the Social-Democrats, introduced universal male suffrage (for those older than twenty-three) with proportional representation. The change happened in an era of pacification, when many of the disputes from the nineteenth century were settled and the political consensus was shifting to more social care and state intervention.Footnote 155 The change had a big impact on the Dutch political landscape, as the number of voters increased from 15 to around 50 percent of the adult Dutch population.Footnote 156 Second, proportional representation increased the influence of political parties. Since every vote counted, parties for the first time operated nationwide and not only in areas where they hoped to obtain a majority.Footnote 157 Last, political parties set the list order and candidates were more likely to be chosen when they were higher on the list.Footnote 158

The motion was initially accepted in 1918 but later that year the AWV asked the NBVHIM to reconsider. The motion proved very divisive and threatened to tear apart the association.Footnote 159 The problem was that the NBVHIM would lose its strict political neutrality by directly interfering in elections. This would make confessional members leave the neutral organization as it conflicted with their convictions. The compromise was to leave the initiative to the individual members. They were encouraged to make use of their pillars by contacting their respective political parties and ask them to place middenstanders or people friendly to the middenstand on their list. If members were not bound to a party (mostly neutral members), they were advised to vote for the newly established Middenstands Party.Footnote 160 Most middenstanders apparently voted for their respective pillars because the Middenstands Party received only 12,674 votes (or around 23 percent of the combined membership of the three unions).Footnote 161 A quarter of those votes were concentrated in Amsterdam, indicating that mostly liberal shopkeepers voted for this party.Footnote 162 The conflict shows how pillarization precluded direct cooperation. Rather than centralizing efforts, members were organized along religious lines at the base, and cooperation was limited to the top of the organizations. The compromise only entrenched this discord.

Besides trying to influence which officials got elected, the associations worked on expanding and formalizing their influence on the government. The NBVHIM did so by proposing a consultative body for the middenstand, named the Middenstandsraad, in May 1917. Everwijn responded positively.Footnote 163 Not much later, in September 1918, their long-term advisor Aalberse became minister of the newly created Ministry of Labor. Aalberse was a longtime advocate of letting organized business play a larger role in the creation of social and economic legislation as a way to reorganize economic life more harmoniously. Already in 1903, he proposed the formation of something similar to the Middenstandsraad and gradually found support for this idea.Footnote 164

By 1919 the political climate was ready for the progressive ideas that Aalberse promulgated. World War I had increased the number of unionized workers, during the war the government and business had experimented with cooperation, and the failed Socialist revolution in November 1918 upped the pressure for social reform.Footnote 165 The government declared its support for reforms, and a first consultative body for industry, named the Nijverheidsraad (Industry Council), was launched in January 1919. The Catholic parliamentarian and president of the Catholic NRKMB, J. A. Veraart, however, asked Aalberse to include representatives of small firms, nominated by the three middenstander federations. The original plan was to expand the Nijverheidsraad, but eventually they decided to create a separate council named Middenstandsraad.Footnote 166

The Middenstandsraad was operational by September 1919 and consisted of representatives of the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade, and the three main middenstand federations: Catholic (NRKMB), Protestant (CMV), and neutral (NBVHIM).Footnote 167 Its function was, similarly to the Nijverheidsraad, that of an independent advisory body to the minister of agriculture, industry, and trade. The Catholic parliamentarian and president of the Commission for the Middenstands Survey, Baron A. I. M. J. van Wijnbergen, became the council’s first president and remained so for thirty years.Footnote 168

In February 1920, a third council, the Hoge Raad van Arbeid (High Council of Labor) was instituted. This council served to improve the communication and cooperation between employers, employees, and the state. As employers, the middenstanders occupied three out of the forty seats on this council: one for every pillar.Footnote 169 In both councils, all three pillars were on equal footing and relations were amical. This helped the groups to overcome the divisions caused by pillarization and to act as a unified front in defense of the middenstand on the highest echelons.

More importantly, the councils gave real power to the three federations. The councils allowed direct access to the executive branch of the state, while the relations with the pillarized political parties and to a much lesser extent through the Middenstands Party (which had only one seat in Parliament) allowed them to put their topics on the agenda.Footnote 170

Weathering a Crisis

Shortly after this institutional development with the Middenstandsraad as capstone, the Netherlands was hit by a financial crisis (1921–1923).Footnote 171 This was particularly destructive for the middenstandsbanks, causing distress for about a third of the banks.Footnote 172 Colvin found that banking cooperatives were less vulnerable than incorporated banks as a result of the super-liability of directors.Footnote 173 On the one hand, the incorporated Hanzebanks failed spectacularly, shaking the faith in the SME banking system. On the other hand, the federations and most of the local associations continued their operations. The Catholic Hanze unions suffered a sharp decrease in membership from around twenty-three thousand to less than ten thousand members, showing the link between the associations and the banks (Fig 3). Nonetheless, they continued to provide services, organize conferences, and publish local newspapers. Credit disappeared from the associations’ agendas and much of the debate on credit and the situation of the banks moved to the background. The associations reported on the unfolding banking debacle, both with a mix of surprise about the situation and with optimism to minimize reputational damage.Footnote 174

Figure 3 Membership of the middenstand federations, 1907–1936.

Protestant was counted under neutral until 1918. The Catholic Hanze of Breda is missing data for 1907. The Catholic Hanze of Limburg is missing data for 1926 and 1929. In 1920 the Catholic Hanze of Limburg had around nine hundred members Source: Afdeeling Handel van het Departement van Landbouw, Nijverheid en Handel, Overzicht van de in Nederland bestaande Patroonsvereenigingen, 1907, 1909, 1914, 1921, 1926, 1929, and 1936, 2.06.001/3893, 3900, 3921, 3924, 3940, 3953, and 3986, NA.

The Central Middenstandsbank absorbed many of the failing middenstandsbanks, and by 1925–1926 ran into trouble itself, suffering heavy losses and exceeding the state guarantee.Footnote 175 The established political connections were eventually what saved the Central Middenstandsbank and the wider SME banking system. Treub, who was still heavily involved, pushed for centralization of the system into the Central Middenstandsbanks.Footnote 176 And the Protestant H. Colijn, minister of finance (1923–1925) and later prime minster (1925–1926), had strong connections to the Boaz Banks. He further extended the state guarantees to the Central Middenstandsbank.Footnote 177 A governmental commission comprising bureaucrats, bankers, leaders of the Catholic and neutral middenstand federations, and a Protestant politician was tasked with assessing the viability of a centralized middenstandsbank.Footnote 178

Eventually, the Central Middenstandsbank, together with the Middenstandsbank of Limburg and the Boaz Banks, were integrated into the NMB in 1927. The deal made by the commission reflected the political influences and compensated for several grievances. The Central Middenstandsbank was valued at less since it had already received ample subsidies. The Catholics were compensated for the failure of the Hanzebanks, and the Boaz Banks were overvalued to ensure the support of the Protestant pillar.Footnote 179 Catholic association membership slightly increased between 1926 and 1929, while neutral associations declined. By the 1930s, when the NMB had regained the middenstanders’ trust, membership sharply rose again (see Fig. 3).

The Middenstandsraad, as a voice for the three unions, barely interfered in the banking crisis of the 1920s. The direct connections between associations and politicians of their respective pillars not only sufficed but also were more appropriate when lobbying for the survival of their respective parts of the banking system. When in the 1930s the crisis hit middenstanders regardless of denomination, the Middenstandsraad did interfere and proposed government-funded guarantee institutions (named Borgstellingsfondsen) to help small firms. These started in 1936 and became a building block of the afterwar credit allocation system.Footnote 180

Conclusion

In the timespan of seventeen years, the middenstander movement evolved from a marginal phenomenon to a well-organized group that exerted real political influence. I described the path it took to reach that outcome and how it shaped that path along the way. Its quick rise to political relevance was not necessary nor evident. Middenstanders continuously adapted to local circumstances and effectively maneuvered the political realities to make their movement a success.

In line with Verdier, I argue that class cleavage aided the battle for relevance of small firms. The fear of class warfare made conservative political parties more receptive toward a potentially stabilizing movement. However, small entrepreneurs in the Netherlands, as in other parts of Europe, had to navigate through a difficult Olsonian collective action process before being in a position to exert sufficient influence and obtain subsidies. Associations needed to forge a common identity for a notoriously heterogenous socio-economic group, and offer value to potential members to convince them to join.

The topic of insufficient access to credit was crucial in binding together a heterogenous group for small entrepreneurs and in lobbying the government for support. Insufficient access to credit was one of many possible unifiers. However, because of the commonality of this issue, the incentives set by the government, and for practical reasons, it became the central reason the associations could gain traction with members and engage the government. This turned it into a virtuous circle with expanding services drawing more members until the financial crisis disrupted many credit institutions. Nonetheless, membership remained high and the associations continued using their political power to lobby for the survival of their banks.

This in-depth case study nuances Verdier’s thesis. Dutch small-firm associations did not simply gain political relevance or plan to extract state banking. Rather, state banking was the result of a decades-long interaction between the state and small-firm associations that started for reasons other than access to credit. It was coincidences, path dependencies, and personal connections that led to state banking. The NMB was not the successful starting point of the second wave of state banking in the Netherlands but the outcome of a failed attempt at creating a system based on subsidies rather than direct government intervention.

Throughout this period, associations had to operate within the political framework of constraints, much like Lemercier described. In line with Colvin, I found that socio-cultural and political contexts, especially pillarization, played decisive roles in shaping both the associational process and financial system development. The government’s strategy to integrate interest groups into coherent structures spurred the development of national federations, but pillarization caused them to split along ideological lines. This led to duplication of functions and intragroup competition, but it also gave the young movement the support of established political parties. Personal connections also appeared to have been crucial for success, notably the relations between Nouwens and Everwijn and among Meuwsen, Bos, and Treub.

The Dutch case highlights several avenues for further research and reflection. First, there is a need for more micro-level qualitative research regarding financial system development and political association. Many things happen for reasons of personal interaction, context, or even chance, and these are not easily captured through more formal quantitative research methods. Still, they deserve attention to fully understand these topics. Second, it is necessary to include SME lobby groups and petite bourgeoisie movements in the wider history of financial systems, since their links to state banking and state intervention were historically large, as demonstrated in the case of the Netherlands. Researchers such as Verdier, Carnevali, and Prasad have started along this path, but more explicit comparative research, especially between places where petite bourgeoisie associations failed to arise, as was the case in the United Kingdom or the United States, could help explain peculiarities in national financial systems.Footnote 181