Ghost ships are difficult to catch, especially in the polar regions. They occasionally appear suddenly out of ice, fog and mist, only to disappear again. Just as suddenly, they also appear in newspapers time and again.

When Sir John Franklin’s flagship HMS Erebus was discovered at the bottom of the Canadian Arctic sea in September 2014, the term “ghost ship” once again appeared in the media. The business magazine Forbes, for example, ran the headline “Wreck Of ‘Ghost Ship’ Found In Arctic” on 10 September (Rodgers, Reference Rodgers2014) and when HMS Terror, the second expedition ship, was found two years later, almost exactly the same headline was used (Jones, Reference Jones2016). In between, a documentary film about Franklin’s last expedition and the discovery of Erebus was shot in a lavish international co-production, which was broadcast in the USA in 2015 as part of the prestigious popular science TV programme Nova under the title “Arctic Ghost Ship”, and ran in a slightly different version as “Hunt For The Arctic Ghost Ship” in the same year on the UK’s Channel 4 series Secret History (Finney, Reference Finney2015a,b). However, the two ships, part of the most ambitious British expedition to find the Northwest Passage up to that time, were not actually ghost ships at all.

A ghost ship is either a ship that appears unexpectedly on the horizon and disappears just as suddenly if one attempts to approach it, or it is a ship that sails across the sea although it has no crew – that is, they are either dead or have disappeared without trace.

The best-known example of the first case is certainly the legend of the Flying Dutchman, probably the most famous of the phantom ships. It tells of a 17th century Dutch captain – usually in the service of the Dutch “United East India Company” (VOC) – who defied wind and weather and sailed so fast across the sea to be better and more successful than all the others that everyone eventually believed he must be in league with the devil. His reckless and unchristian behaviour eventually led to being cursed by God. Until Judgement Day, he must perpetually battle the storms off the Cape of Good Hope without ever reaching the saving harbour (see, for instance, Golther, Reference Golther1911; Kalf, Reference Kalff1923; Gerndt, Reference Gerndt1971).

The sightings of the Flying Dutchman and its sudden disappearance can be explained by a mirage – atmospheric reflections, which are favoured by the weather and currents off the Cape of Good Hope (Eyers, Reference Eyers2012, p. 68–70; Peterson, Stramma & Kortum, Reference Peterson, Stramma and Kortum1996). Already William Fitzwilliam Owen, RN, one of the most experienced captains in the Royal Navy’s Discovery Service, had suspected this in 1821 when he sighted his consort ship off the Cape, although it was still 200 nautical miles away beyond the horizon (Owen, Reference Owen1833, p. 141–142).

Getting closer to the origin of the legend proves to be more difficult, as is so often the case. According to Dutch literary scholar Agnes Andeweg (Reference Andeweg2015), no references to the legend can be found in Dutch sources of the 18th and early 19th centuries (Schultz, Reference Schultz2019). However, her recent thesis that the legend was therefore a British invention from around 1800 to portray the Dutch, who were not well spoken of at the time, as godless and evil is not entirely convincing. It overlooks the first known reference to the story: In a voyage narrative published in 1790, the Scottish author named John MacDonald (Reference MacDonald1790, p. 267) only briefly summarises what he calls a “common tale” among sailors, without mentioning the godlessness of the captain. It may well be that the story, possibly indeed mentioned here for the first time in writing, was more popular among English sailors than among Dutch ones. This would also be supported by the fact that in many versions the captain has a name that sounds typically Dutch to foreign ears, beginning with “van”. However, the tale was certainly not a new one. The fact that it has been so widespread since the 1820s, especially in English but also in German-speaking countries (Gerndt, Reference Gerndt1971), is certainly at least partly due to a version of the legend that appeared anonymously in May 1821 in a widely read Scottish literary journal, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine (Howison, Reference Howison1821). The tale, which was reprinted many times, had been written down by the Scottish doctor John Howison (1797–1859), who had worked for the East India Company and also lived in Canada for some years, after his return to Scotland (Strout, Reference Strout1959, p. 78). Just two months after its publication in Edinburgh, the story appeared in German in Stuttgart without any indication of its origin (Howison, Reference Howison1821a). At that time, the legend was still unknown among Germans (Barth, Reference Barth1994), at least among landlubbers. But that was soon to change.

The anonymous author of an article about the Flying Dutchman, which also appeared in Stuttgart two decades later on 25 August 1841, presupposed that hardly any reader of the respected ethnographic daily Das Ausland did not know the legend (Anon., 1841h). What was new at the time, though, as he explained not without pride, was that there was indeed an identifiable model for the accursed captain from the end of the 17th century, whose name actually appears in the records of the Dutch East India Company. But his name is not van-something.

The Frisian captain Barend Fockesz really did manage to sail back and forth between Batavia (today’s Jakarta) and the Netherlands several times significantly faster than others (Leupe, Reference Leupe1859). He is thus an obvious inspiration, even if it is not yet clear whether his name appears in the legend before this discovery of 1841. Even if not, however, this does not exclude the possibility that he is indeed the real-life role model of the cursed captain. Perhaps the beginning of the legend of the Flying Dutchman – or at least the answer to the question of why the Flying Dutchman is a Flying Dutchman – lies in the astonishment of the English at this achievement. Parts of the legend, however, may even go back to contemporary accounts of Bartolomeu Dias’ discovery and Vasco da Gama’s first rounding of the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 and 1492, respectively (Frank Reference Frank1979, p. 61–71).

Ships drifting on their own across the seas, on the other hand, should be easier to identify, or so one would think. But as the search for John Franklin and his ships shows, even that is not always so easy. It is still unclear whether Franklin’s ships drifted or were sailed to the spot where they sank, so it remains to be seen whether they actually became ghost ships in the end, as some journalists apparently suspected after the discovery of the wrecks. However, it is now undoubtedly certain that two other ghost ships that were thought to be Sir John Franklin’s were not Erebus and Terror, which only makes this story more puzzling.

In April 1851, an English merchant ship off Newfoundland sighted two three-masted ships trapped in an iceberg that appeared to have been abandoned by their crews. But the captain refrained from approaching the iceberg to investigate. He did not even think it necessary to report the incident to the Admiralty, which only learned of it by chance a year later and which, like the public, was thrown into a frenzy by the news (Anon., 1852). The ensuing investigation led to no concrete result (Great Britain, 1852). The ships were never identified and the whole episode remained another unsolved mystery in connection with the Franklin expedition (Ross, Reference Ross2003).

As this example shows, ghost ships often live up to their name even when they are not phantoms, but a ship actually drifting on the sea, for rarely, is a story as well documented as that of HMS Resolute, which belonged to the squadron sent to the Arctic in 1852 under the command of Sir Edward Belcher to search for the lost expedition of Sir John Franklin. Four of its five ships, including Resolute, were abandoned on Belcher’s orders in 1854 after becoming beset in the ice. HMS Resolute, however, found her way out of the Northwest Passage and back into the North Atlantic on her own. There, an American whaler found her and brought her to the USA, whereupon the US Congress decided to have her repaired and present her to Queen Victoria as a gift. So she returned to England at the end of 1856 (M’Dougal, Reference M’Dougal1857; Sandler, Reference Sandler2006).

But the stories of this resolute ghost ship and the two ships trapped in an iceberg were not the only ones associated with Franklin’s vanished expedition. The expedition’s disappearance was as fascinating and inexplicable to the public then as it is today, just as is the appearance and disappearance of ghost ships. It is therefore not surprising that the German geographer and publicist Karl T. Andree (1808–1875), for example, linked the two stories. As an editor, he urgently needed exciting stories for his illustrated periodical Globus. This was the first German-language geographical journal not aimed at a specialised audience but intended to get everyone excited about geography and ethnography (Belgum, Reference Belgum2013). That is why, for instance, he wrote in the first issue in 1862 about Francis Leopold McClintock’s discoveries of the remains of the Franklin Expedition three years earlier (McClintock, Reference McClintock1859; Anon., 1861), as he could be sure that this would interest a wide readership (Anon., 1862). To add to the suspense, he then linked this account to one about a ghost ship – simply by saying, “Mac Clintock’s account reminded us of another we once read about a death ship in the southern icy seas” (ibid.: 62). The account that then followed is of the ghost ship Jenny, said to be from the Isle of Wight. It was, according to the anonymously published article in Globus, which was very likely edited by Andree himself, sighted in the Drake Passage in September 1840 by the whaler Hope under Captain Brighton. Everybody on board the ghost ship, including the captain and his wife, froze to death after the ship had been trapped in the ice for 71 days, according to the last logbook entry of 17 January 1823, after the fire had gone out the previous day. Captain Brighton took the logbook and returned aboard his own ship and to Europe (ibid. p. 62). So much for the version of events published by Andree. In 1965, the second part of the 1862 article from the Globus was printed in translation in Polar Record (Anon., 1965), which also recounted unsuccessful attempts that had been made to identify the two ships involved in the gruesome encounter more closely (ibid.: 411). Although the hitherto largely forgotten story has since repeatedly appeared in the press and in publications on mysterious phenomena (such as Gaddis, Reference Gaddis1965 and Faiella, Reference Faiella2021) and has even been included in reference works on the history of Antarctica (Headland, Reference Headland1989, p. 129, no. 514), neither a Captain Brighton nor the corresponding ships could be found in any official documentation.

Karl Andree’s sources, on the other hand, can be identified relatively precisely: The story he had “once read about a death ship in the southern icy seas” was certainly a text published anonymously two decades earlier, in early 1841, in almost identical versions in various German-language entertainment journals under titles such as “Das Schiff im Eise” (“The Ship in the Ice”) or “Ein Schiff im Eismeer” (“A Ship in Icy Seas”) and so on. Apart from the title, the main difference is the year of the encounter of the two ships, which is sometimes given as 1839 and sometimes as the previous year, that is, 1840. It appeared in Prague in the journal Bohemia on 14 February 1841 (Anon., 1841) and for the first but not last time that year in Vienna five days later (Anon., 1841a), without a title in the “Vermischte Nachrichten” (“Miscellaneous News”) column of the Wiener Zeitung, the oldest continuously published newspaper in the Austrian capital. In both cases there is no indication of a source. Wherever the journalist who discovered the story first got his information from, he obviously assumed that it was authentic. It is possible that he had it only from an oral source, because so far no English text has been found that could have served as a source of information – neither in newspapers or periodicals nor in travel narratives. One should not forget that the Austrian Empire, unlike today’s Republic of Austria, had access to the sea and was a maritime power, although not a significant one. During the 19th century, sailors from different countries were not such a rare sight in the major inland cities like Vienna, Prague or the twin cities Buda and Pest (today’s Budapest) as one would assume today. It is quite possible that a journalist heard the story about the ship in Antarctic waters from one of them and wrote it down enthusiastically. It then spread throughout the Habsburg Monarchy (for instance, Anon., 1841b; Anon., 1841f; Anon., 1841g) – even reaching Transylvania (Anon., 1841d). In the same time it was also published in major German cities (see, for example, Anon., 1841c; Anon., 1841e). In the German lands, people began to take an interest at this time in the legends of the sea and not only in the legends and fairy tales of the mountains and forests for which the literary Romantics had long been passionate (Gerndt, Reference Gerndt1971). It was certainly no coincidence that after the publication of the story about Jenny, a newspaper dealing with the traditions of foreign countries also published a version of the legend of the Flying Dutchman, in which an attempt was made to trace its origins (Anon., 1841h).

But there was another reason why newspapers could count on a great deal of interest among their readers for such stories in 1841. Shortly before, three official expeditions had set out for the Antarctic Ocean: a French one under the command of Jules Sébastien César Dumont d’Urville (1790–1842), which had returned to France in early November 1840; an American one under Charles Wilkes (1798–1877), which had turned its back on Antarctica already but was still sailing the world’s oceans; and a British one under James Clark Ross (1800–1862), which was then still in Antarctic waters (Gurney, Reference Gurney2000).

This public interest is likely the reason why the cartographer and editor Heinrich Karl Wilhelm Berghaus (1797–1884) chose to publish the story about the ghost ship together with the translations of the reports that Dumont d’Urville and Wilkes had had published in Australian newspapers about their respective discoveries after their return from Antarctic waters (Anon., 1840; Anon., 1840a). Berghaus, however, was a close friend of a key figure in international scientific circles – Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859). Humboldt was always well informed, directly or indirectly, about all discoveries in the southern hemisphere since his own expedition to South America in 1799–1804 (Wulf, Reference Wulf2015; Reich, Knobloch, & Roussanova, 2016). As a result, Berghaus was also up to date and remained sceptical about the veracity of the account of Jenny. Because he could not find the original source, but was only able to trace the story back to its publication in the Wiener Zeitung (Anon., 1841a), he feared that it was probably just a sailors’ yarn after all (Berghaus, Reference Berghaus1841, p. 219).

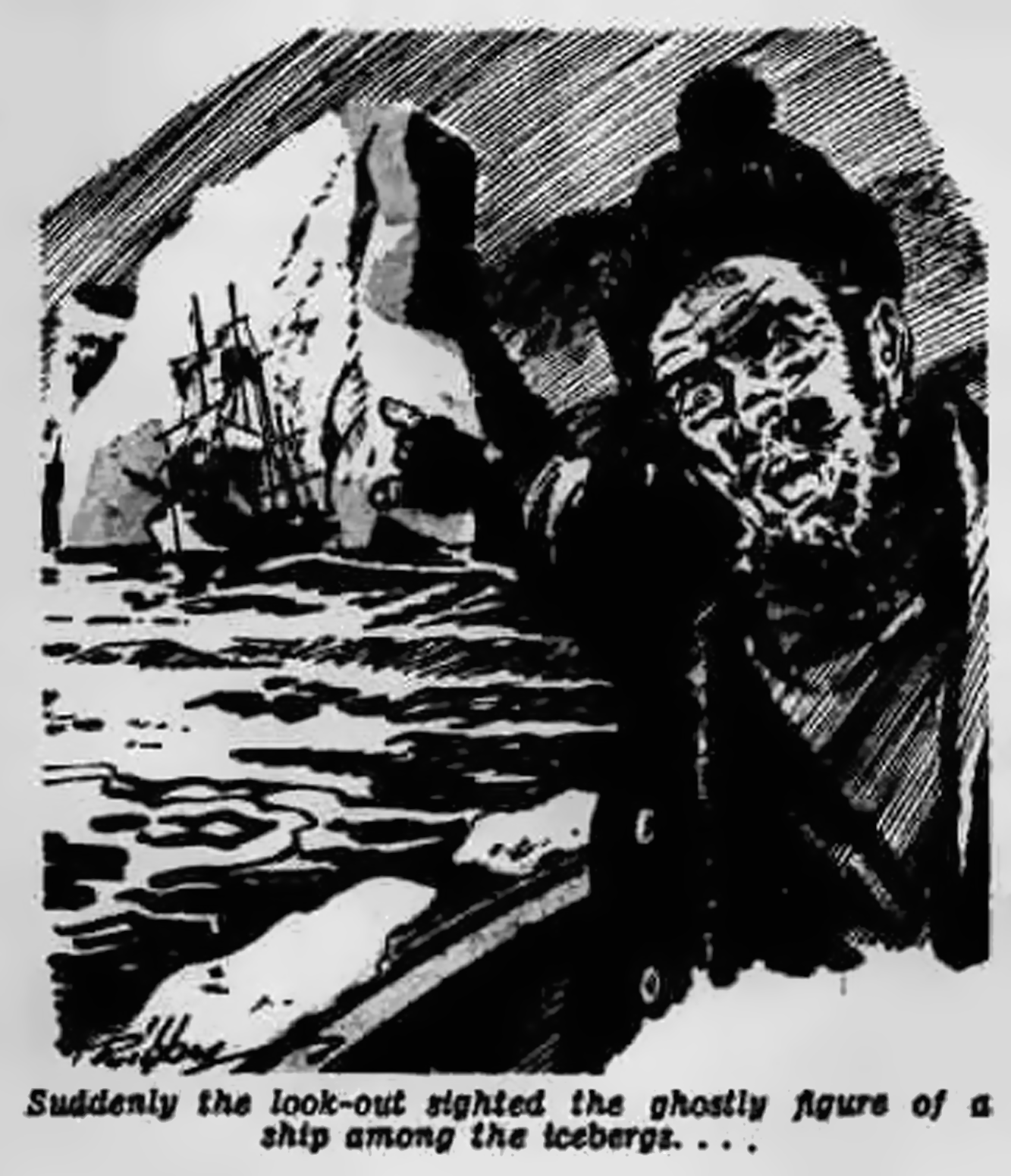

Indeed, the parallels to a story of another ghost ship are striking, even though that tale supposedly began a whole century before Andree published his version of the story of Jenny and took place at the opposite end of the world. Today, this ship is mostly known as Octavius (Harper, Reference Harper2018). Its story continues to appear in newspapers to this day, sometimes even illustrated (for instance Anon., 1961). This ghost ship is said to have been discovered by a whaler under a Captain Warrens or Warren in Arctic waters in 1775, after allegedly crossing the Northwest Passage on its own, coming from the Pacific. The crew also froze to death because the fire had gone out, again including the captain and his wife. In versions from the end of the 19th century, however, the ship bears the name Gloriana (Quiller-Couch Reference Quiller-Couch1895, p. 258–259) instead of Octavius, and even earlier it is, as will be seen, entirely nameless.

The dramatic moment of the discovery of the ghost ship Octavius in a modern illustration from 1961 in the Aberdeen Evening Express (Anon. 1961).

Stories of ghost ships in icy regions appeared, mostly recognisable as sailors’ yarns, in American literary gazettes around 1825 at the latest, although in those days it may still be the Baltic Sea where the crew freezes to death in the ice (Spunyarn, Reference Spunyarn1825). In 1828, several newspapers picked up a story published on 8 December that year in the New York Gazette under the title “Awful Discovery” (Anon., 1828), set in Arctic waters, which, apart from the missing name of the ghost ship, resembles the later stories about Gloriana or Octavius. On 13 December, for example, it was reprinted in the literary journal Ariel from Philadelphia under the title “The Dangers of Sailing in High Latitudes” (Anon., 1828a). The last logbook entry reproduced in the article reads:

11th Nov. 1762: We have now been enclosed in the ice seventy days. The fire went out yesterday and our master has been trying to kindle it ever since but without success. His wife died this morning. There is no relief –. (ibid.)

On 30 December 1828, the story had already crossed the ocean and appeared in the London Courier (Anon., 1828b) and repeatedly in the following years on both sides of the Atlantic, for example, on 6 January 1829 in the Liverpool weekly The Kaleidoscope (Anon. 1829a) and on 14 January 1829 in The Geneva Gazette, a small town newspaper in the interior of New York State (Anon., 1829b).

Presumably this story, like that of the Flying Dutchman, is a tale passed down orally over generations among sailors, in this case especially among Arctic whalers, eventually came to the attention of a journalist, was recorded and published, and began to circulate through the press.

It is impossible to tell exactly why this happened in the winter of 1828/29, as the story appeared in the press without any comment. Nevertheless, it seems reasonable to assume a connection to the Royal Navy’s expeditions to the Arctic at that time. At the end of September 1827, John Franklin had returned to England from his second overland expedition to the north coast of the North American continent and was celebrated as a hero (Berton, Reference Berton2001, p. 88–95). William Edward Parry had also arrived back in London at the same time. After three more or less unsuccessful attempts to cross the Northwest Passage, Parry had made an attempt to reach Asia via the North Pole. After all, the theory of the open polar sea and the ice-free pole still met with great interest in the press, in politics and among the general public, although those who knew the Arctic did not believe in it (Potter, Reference Potter2004). Unsurprisingly, Parry had not succeeded in crossing the North Pole. But at least he had come closer than anyone else up to that point (setting a new farthest north), which was enough to celebrate him as well (Berton, Reference Berton2001, p. 95–103). Yet it was soon obvious that the Admiralty would not be sending another expedition to the Arctic any time soon, despite the continued interest in the subject. The “Awful Discovery” of the New York Gazette must have come in handy, since it brought the paper the attention of the readers, as the echo in other newspapers demonstrates.

A clue to the possible origin of the tale is still given by the dates mentioned in the text, while the ever-changing names over time, as far as I can see, do not really lead anywhere. The year 1762 noted in the logbook of the ghost ship was not a particularly good year for whalers. The Dutch, for example, had sent 139 ships into the Greenland Sea, one more than the previous year, and 27 into Davis Strait, four more than the year before, but they caught only 190 whales instead of the 358 from 1861, and lost four ships, one more than in 1861. The catch of the English and Scottish whalers also declined, as did that of the ships from Hamburg (Lubbock, Reference Lubbock1937, p. 100–101; Holland, Reference Holland1994, p. 125). The dates mentioned in the legend, however, may have less to do with whaling in these waters than with the passage through which the ghost ship supposedly passed. In the mid-18th century, the Arctic and the Northwest Passage were on everyone’s lips, because apart from the United Kingdom, Russians, Spaniards and Frenchmen were also interested in them (Williams, Reference Williams2002). Ivan Sindt was commissioned to explore the Bering Strait in 1761, Vasily Chichagov was to find a passage to Alaska from Spitsbergen (Svalbard) (Black, Reference Black2004, p. 80–86; Holland, Reference Holland1994, p. 126–30) and in 1764 a Royal Navy expedition under John Byron set sail (Byron, Reference Byron1964) to try to find the entrance to the passage from the Pacific after several unsuccessful British attempts from the Atlantic. However, none of these expeditions were successful.

In 1775, the year the ghost ship appeared off Greenland, interest in a passage through the Arctic was therefore unbroken. This time, Spanish expeditions in 1774 and 1775 had explored the northwest coast of the North American continent in an unsuccessful search for the passage (Holland, Reference Holland1994, p. 139).

In the Greenland Sea and Davis Strait, it was indeed stormy and icy that year. A great many British whaling ships had set out for the Arctic (105) but were not very successful. The Dutch sent even more that year (135), but they killed only 105 whales (Holland, Reference Holland1994, p. 139; Lubbock, Reference Lubbock1937, p. 115). According to a report in the Leeds Intelligencer, the Dutch lost 11 ships from their whaling fleet (Anon., 1775), which was far more than the usual annual losses of two to four. That year marked the end of the heyday of Dutch whaling (Dekker, Reference Dekker1971) and, according to recent climatological research (Kuijpers et al., Reference Kuijpers, Mikkelsen, Ribeiro and Seiding2019), represents the peak of a cold phase in the North Atlantic that lasted about 60 years, with low water temperatures and heavy sea ice formation. In addition, a hurricane that year hit the British colonies of Virginia and North Carolina, which were in the process of breaking away from motherland (Williams, Reference Williams2008). That storm, or perhaps a later one, subsequently devastated Newfoundland and possibly even reached the Greenland Sea (Ruffman, Reference Ruffman1996), leaving thousands dead. Perhaps the conditions and events of that time are indeed the beginning of the legend of the ghost ship in the Greenland Sea, just as the legend of the Flying Dutchman may have begun with the amazement at Fockesz’s maritime feats.

The Arctic legend, in turn, might be the beginning of the legend of the ghost ship Jenny.

If one compares the quotation from the logbook of the nameless ghost ship with that from Jenny’s logbook, the similarity is unmistakable. The entry of Jenny as reproduced in the story in the Prague entertainment journal Bohemia (Anon., 1841, p. 3) states in translation:

January 17, 1839. Today it is seventy-one days that our ship has been trapped between the ice. All our efforts were in vain – Last night the fire went out, and all our master’s efforts to rekindle it failed – This morning his wife died of hunger and cold, as did five sailors from the crew. Hope no more!

Not only the events but also the two logbook entries are so similar that one can safely assume that this story is also the model for the one that haunted German newspapers in 1841 – at least the part about the frozen crew.

Thus, a ghost ship that appeared in the Arctic in 1775 and disappeared again after a brief encounter with a whaler reappears, so to speak, 65 years later off the Antarctic Peninsula under a different name, and found by a different skipper. In other words, a story that appeared in American newspapers at the end of the 1820s and disappeared again reappears a decade later in German and Austrian newspapers under a different name. The story seems to be a classic wandersage or migratory legend.

This distinguishes it from the legend of the Flying Dutchman, which was originally tied to a specific place – the Cape of Good Hope. The fact that the Flying Dutchman was eventually sighted in other places had another reason: the tale also found its way more and more frequently into literary texts from the beginning of the 19th century onward, making it known worldwide. Over time, however, at least until the end of the age of sailing, the name became more and more synonymous with the phantom ship as such. It was only in the age of steam, when the sighting of a sailing ship became something unusual, that one can speak of adaptations and a wandering of the legend itself (Gerndt, Reference Gerndt1971).

The legend of the ship in the polar sea is more like urban legends in this respect, such as the one about tourists who rent a yacht from which they then decide to go for a swim in a calm. Before jumping overboard, however, they forget to lower a ladder, which is why they fail to get back on board and therefore drown (for example see Brednich, Reference Brednich1991, p. 67). This legend may actually have originated after the discovery of an empty drifting boat rented by tourists, as a possible explanation for their disappearance without a trace, or from a joke about the stupidity of tourists. In the meantime – presumably as a warning – tourists are told the tale as true in almost every harbour where boats can be rented. In fact, this legend has now travelled around the world.

That the legend of the Arctic ghost ship migrated south is unsurprising given the interest in the South Pole that finally increased in the late 1830s, not only among whalers and sealers but now also among monarchs, politicians, naval officers and scientists in Europe and the USA (Gurney, Reference Gurney2000). Along the way, it has changed without really needing to – as is usually the case with legends or folk-tales. When exactly the events took place, what the captain’s name and that of his ship was, is actually irrelevant; either way, the legend itself remains an exciting story for listeners or readers.

Getting to the bottom of legends and to their historical core, or even tracing how they might have come about, is usually tricky because they are passed down orally, changed and adapted to new circumstances. Moreover, the story usually results from an amalgamation of events that could have happened this way, but probably never did. That has to do with remembering and story-telling: when recounting experiences, everyone tries to present them as excitingly as possible and in a way that is understandable to the listeners. That way, if necessary, storytellers draw on patterns known by the audience. Additionally, they supplement their own story with similar ones that fit in, to reinforce the narrative intentions (Vansina, Reference Vansina1985; Welzer, Reference Welzer2008, Reference Welzer2010).

The fact that legends, by their very nature, claim to be true even proves to be an advantage in some cases, as in this one, because the unusually precise details that seem to prove this veracity are preserved for precisely this reason, despite all the changes. This makes it possible, on the one hand, to establish that the story about the nameless ship that surfaced in 1828–30 is the same legend as the one about the ships Gloriana and Octavius. On the other hand, these details often still come from the stories that were incorporated into the legend, so that one can trace its origin – although never with absolute certainty. In the end, the analysis of a legend must always remain speculative, as in this case, and scholars will probably argue for all eternity about the extent to which legends contain a historical core at all, and what that core might be.

What is at least as fascinating, if not more so, however, is to show how an 18th-century Arctic ghost ship became a 19th-century Antarctic one, and which parts of other stories could have given rise to this new tale. It is therefore sufficient to note once again that the legend of Jenny essentially goes back to an older, Arctic one, as is clear from the similarities mentioned. More interesting, however, are the differences.

The last entry in the logbook of Jenny bears the date 17 January 1823 – a date that is made up of two dates that were familiar at the time to everyone who had ever been in Antarctic or sub-Antarctic waters, or who had ever studied Antarctica: on 17 January 1773, a ship had officially crossed the Southern Polar Circle for the first time, James Cook’s HMS Resolution (Cook, Reference Cook1961, p. 80), while on 17 February 1823, James Weddell (1787–1834) had sailed through the pack ice into the sea later named after him, and passed Cook’s southernmost position, beating the 50-year-old record, before he too turned back three days later, still without having sighted Antarctica, to fight his way back north through the pack ice (Weddell, Reference Weddell1825, p. 32–44).

The Scottish sealer had indeed returned from the ice with his ship without freezing to death, but what had been said among the other sealers about his disappearance in the pack ice is just as unknown as what his sailors told others about the voyage. This may well be the origin of the legend – or more precisely, its southern version, because Weddell’s ship was called Jane. So, it is probably not a coincidence that the ghost ship is named Jenny, especially since no other whaler or sealer named Jenny is recorded at the time. Jenny is in fact nothing other than the original diminutive form of Jane (Withycombe, Reference Withycombe1977).

The fact that the other ship in the southern version of the story has a new name, and is called Hope, makes the story even more dramatic, since it could not bring hope to the ghost ship. But it is probably no coincidence either. It might have come from a real ship as well, because Jane was not alone in the ice in February 1823. She was accompanied by a cutter under the command of the Scotsman Matthew Brisbane (1787–1833). Although the small consort ship was not named Hope but bore the rare and rather hard-to-remember name Beaufoy, Brisbane was actually to command a ship named Hope in 1828 – the year when stories about a ghost ship in the ice began to appear in American newspapers. Again, the voyage in Antarctic waters was dramatic, as Hope ran aground off South Georgia on 23 April 1828. On 7 March 1829, after almost a year on the island, Brisbane left South Georgia with only half his crew. One man had frozen to death and ten of the others did not want to embark on the daring voyage. In a small sloop cobbled together from wreckage found on the island and the remains of Hope, he wanted to reach Montevideo. On 5 April 1829, Brisbane and his boat crew successfully reached the South American coast. But it was to take another month before he arrived in Buenos Aires and was able to officially report the loss of Hope to the British Consul General. The Consul General then initiated a rescue operation. Brisbane set off again for South Georgia on 17 September 1829 with the chartered American ship Betsy, following a voyage to the Falkland Islands and States Island, finally reaching South Georgia and rescuing the part of his crew that remained there. It is quite possible that the stories told about Brisbane’s adventures, which made the rounds around the world as a sailors’ yarn in the ports between South America and Australia and along the Roaring Forties, became intermingled, and so Captain Brisbane became Captain Brighton. For the whalers and sealers of the southern hemisphere at that time, Brighton was not so much a seaside resort in faraway England but rather one of the newly emerging port towns in Britain’s Australian colonies (Brighton in Tasmania being the best known one in those days) – just like Brisbane. So a confusion was likely. Without the files on the Falkland Islands in the Foreign Office and the Colonial Office, as well as a few newspaper reports, we would probably know nothing today about the accident of Hope and Brisbane’s rescue operation (Great Britain (1829), (1829a); British Packet and Argentine News (Buenos Aires), 20 June 1829: 2).

Another voyage of two sealers to Antarctica is also almost forgotten but was certainly a topic of conversation among sailors at the time and thus may have become part of the legend of Jenny: The voyage of Hopefull and Rose (Gould, Reference Gould1946; Jones, Reference Jones1965).

After John Biscoe’s (1794–1843) successful circumnavigation of Antarctica (1830–33) and the discovery of Enderby Land (Biscoe & Enderby, Reference Biscoe and Enderby1833; Biscoe, Reference Biscoe1835; Biscoe, Reference Biscoe1901), the ship’s owners, brothers Charles (1798–1876) and George Enderby (1802–1891), tried to mount another expedition. To minimise the financial risk, they tried to get the Royal Navy on board, hoping the Admiralty or the Treasury would reimburse the likely commercial losses. After William Smith (1790–1847) had discovered the South Shetland Islands in Williams in 1819, the Royal Navy had chartered the brig shortly afterwards and had sent it back with some naval officers on board under the command of Master Edward Bransfield, RN (1785–1852), successfully verifying Smith’s information (Campbell, Reference Campbell2000).

In 1833, the Enderby brothers, more interested in geography and discovery than in their whaling and sealing trade (Ash, Reference Ash2015), made a similar proposal to the Admiralty. Surprisingly, the Admiralty agreed, although they were not really interested in the South Pole at the time. According to the Enderbys’ plan, the ships they equipped would sail south from the Cape of Good Hope via the Kerguelen Islands towards Antarctica and then sail west to search for new land and seals in continuation of Biscoe’s Enderby Land. However, Francis Beaufort (1774–1857), hydrographer to the Admiralty, pointed out that the ships would have to sail against the wind on such a route and that Biscoe had not seen any seals in Enderby Land. He therefore suggested to try again from the Falklands, following Weddell’s track (Beaufort & Enderby, Reference Beaufort and Enderby1833). The Enderbys agreed and the two ships set off south in July 1833 with lieutenant Henry Rea, RN, on board Hopefull. From the outset, the expedition was ill-fated, for while the Enderbys considered Rea to be a passenger – or rather supercargo – the latter probably saw himself as captain and expedition commander. John Biscoe, who originally had been appointed skipper of Hopefull by the Enderbys, disembarked while the ships were still in England, and his two successors left in the course of the voyage south. Hopefull reached Port Louis in the Falklands on 23 October 1833. From there, under Rea’s command, she finally set off in company with Rose towards Antarctica, although it remained unclear to the inhabitants of the town exactly where they were heading.

One of them finally noted on 9 January 1834 that two ships had arrived the previous day, one of which was “the schooner Hopeful [sic.], Captain Rea – the cutter Rose was lost in the ice near the New South Shetlands to the south” (Helsby, Reference Helsby1833, p. 30–31). This was confirmed not only by Henry Smith (1797–1854), the first British governor of the Falkland Islands who had just arrived in the other ship which had arrived that day, in his report to London (Smith, Reference Smith1834) but later by Henry Rea. In a letter Rea informed the Admiralty on 21 May 1834 about the return of Hopefull to England:

… having lost our tender among the Ice in Lat. 60° 17′ South, Long. 53° 26′ W. and found the field Ice so solid that a passage to the southward could not be found although every exertion was made. (Rea, Reference Rea1834), quoted by Jones (Reference Jones1965, p. 240), and Gould (Reference Gould1946, p. 395)

He also promised to hand over the map of the voyage and the logbook to the hydrographer, but neither can be found anywhere any more. Therefore, almost nothing is known about the voyage of these two ships into the ice, apart from the recollections of a former crew member sixty years later (Foxton, Reference Foxton1893).

When it comes to dates and even the name of the ship, which he calls Hopewell, his memory admittedly fails John Greenlaw Foxton (1811–1903), by then over eighty. Icebergs and pack ice obviously made such an impression on him that his memory of the encounter with them shifted his positional data: writing his account in 1893 he gave off the top of his head locations that are 10° too far south. The drama of the events, on the other hand, obviously still remained vivid in his memory:

While we were down among the ice, it was intensely cold. Whenever we desired to shorten sail in tempestuous weather, we had to send hands aloft with heavy hammers, to smash the ice about the topsail sheets before they could be moved. (ibid.: 65)

Several times the ships were in danger of being trapped in the ice, but always escaped, as Foxton recalls. But then their luck ran out:

As we approached 70 degrees south, we saw high land covered with snow, and in our endeavour to approach it, we became again blocked in, with very little space of clear water to work the vessels in for several days. At length, two small openings appeared, on one each side of a large iceberg. We made the signal, “endeavour to escape”. We in the schooner passed out on the north side of the berg; unfortunately, the tender took the south side, and when she hove in sight again had a signal of distress flying. I went on board immediately and found her in a sinking state. Both carpenters condemned her utterly. She had been crushed by two enormous icebergs closing upon her as she passed through. All available hands were set to work bailing and pumping and saving provision, all in casks were thrown overboard; our endeavours being greatly frustrated by a dense fog of some hours duration. It took 15 h to accomplish, during which time myself and the boat’s crew subsisted on grog and biscuit. The tender (The Rose) was then abandoned; and she very soon went down head foremost […]. (ibid.: 61–2)

This is the only account of the demise of Rose that now survives, but Foxton was certainly not the only one who retold it again and again.

These recollections of the sinking of Rose are an example of two things: as precise and real as the stories may seem because of their names and exact dates, names and dates quickly become blurred in memory. The drama, however, which makes a good story, remains.

Looking at what has been compiled and presented here, it is no wonder that no evidence for the existence of Jenny could be found. Everything points to it being a legend, even if, as is so often the case, this sailors’ yarn is not entirely plucked out of thin air or springs from the imagination. Legends are so believable because they evoke associations with familiar things in the listener, because they do not come out of nowhere, but rather unconsciously than consciously arise from parts of well-known stories that are blended together, as in this case from a legend about an Arctic ghost ship and tales about James Cook’s and James Weddell’s well-known expeditions as well as those of the now almost forgotten voyages of Matthew Brisbane and Henry Rea. When interest in Antarctica faded again for decades after the return of James Clark Ross to England in the autumn of 1843, the legend of Jenny also disappeared from the newspapers.

Without the reprint in Polar Record (Anon., 1965), the tale would probably have been long forgotten. It did not appear in either English, Scottish or US newspapers. In 1934, however, it suddenly turned up in Ireland in the North Down Herald (Anon., 1934) as a summary in an article about unsolved mysteries of the sea. The occasion was that there had been a particularly large number of accidents and disasters at sea that winter because of the bad weather. Perhaps the interest in ghost ships was reinforced by the fact that at the time, an abandoned ghost ship had actually been drifting through the Arctic since 1931: SS Baychimo, which had been sighted several times in 1934 (Harper, Reference Harper2013; Dalton, Reference Dalton2006). Whoever told the story to the paper knew a version that could be traced back to Karl T. Andree’s Globus, because now the story was supposed to have taken place in 1860. At the same time, there is also an echo of the legend of the Arctic ghost ship, for when Hope encountered Jenny, it is said to have been “in the Antarctic, south of Davis Strait” (ibid.). This is nonsense as a location, since Antarctica is naturally south of Davis Strait, which is known to be in the Arctic. But it is clear evidence that the story migrated from the North Pole to the South Pole. The fact that it was published in this newspaper is no surprise. In the Irish county of Down, the press could always count on an interest in such topics, since Captain Francis R. M. Crozier came from there, who had been in Antarctic waters with James Clark Ross and then disappeared in the Arctic with Franklin.

By 1936 the story had emigrated to Australia (Anon., 1936) and from then on circulated in Australian newspapers. This time, the ship is said to have been sighted in the Antarctic waters south of Australia in 1860 rather than in 1839 or 1840 in the Drake Passage. In this and the later versions, the crew of Hope even believe the ghost ship to be Flying Dutchman at first. This is a clear indication that we are dealing with a later embellishment, because neither in the 18th nor in the first half of the 19th century would sailors have expected Flying Dutchman to appear in the polar regions. The Brisbane Telegraph (Anon., 1938) insisted that the story was real, and even said that Jenny had been sighted not only by Hope but also by other ships. The legend had once again migrated and been adapted to times and local conditions.

But the Arctic ghost ship did not reappear in the newspapers only at the end of 19th century as Gloriana (Quiller-Couch, Reference Quiller-Couch1895, p. 258–9) but had already done so in the 1850s. With Sir John Franklin’s expedition setting out in 1845, the Northwest Passage had become public interest again. It was generally assumed that the expedition would be heard of again within a year or two (see, for example, Anon., 1847a,b). By the autumn of 1846, after the excitement had died down and there was nothing new to report while waiting for HMS Erebus and Terror to reappear in the Bering Strait, the earlier article about the ghost ship was probably retrieved. It was widely assumed to have originally appeared in the Westminster Review, although it is not to be found there. Between October 1846 and August 1847, the tale appeared repeatedly in Irish, English and Scottish newspapers (for instance see Anon., 1846; Anon., 1846a,b,c). The story apparently also aroused interest in the colonies, for George Powell Thomas, a captain in the Bengal Army who was also active as a draughtsman and painter, decided to give it a literary treatment and to make a poem out of it. Both appeared in a widely read British military journal in May 1847 (Thomas, Reference Thomas1847).

Unlike the legend of the Flying Dutchman, which 19th-century writers fell upon with enthusiasm (Gerndt, Reference Gerndt1971), those about ghost ships in the polar regions hardly found their way into fiction, with exceptions such as this one, as Elizabeth Leane (Reference Leane2012, p. 166–170) noted during her research on Antarctica in literature. Leane is also, as far as I know, the only one who has looked more closely at the stories about the Antarctic and the Arctic ship. However, she mistakenly considers George P. Thomas’ 1847 publication and Karl T. Andrees’ publication of 1862, which she apparently only knows in the 1965 translation, to be the first appearances of the respective legends. She therefore concludes that the legend of the ghost ship in the Northwest Passage was moved from Arctic to Antarctic waters for the sake of piety after the discovery of the demise of the Franklin expedition in 1859. This is untenable, though, because both legends, as we have seen, were already circulating in the press long before HMS Erebus and HMS Terror even set sail.

That the Arctic legend reappeared in the British press in the autumn of 1846 and in the US press in February 1847 at the latest (see Anon., 1847), on the other hand, is indeed most likely connected with the Franklin expedition, although none of the newspapers that reprinted the tale explicitly referred to the expedition in connection with the story. It was not merely a matter of bridging the time until there was news of the expedition. By late 1846/early 1847, a discussion had begun in England about whether to continue to wait or to send a search expedition for Franklin. In the end, the Admiralty in London decided against it and instead asked the Arctic whalers and the Hudson Bay Company to keep their eyes and ears open (Lambert, Reference Lambert2009, p. 179–180; Ross, Reference Ross2019, p. 28–29). At the time, the mention of the catchword Northwest Passage was apparently enough to evoke the right associations among readers, and not just in England. By the 1850s, when the search for the expedition was in full swing, while waiting for the mystery to be solved the legend reappeared in newspapers and magazines, occasionally – as in 1854 in the then brand new United States Magazine of Science, Art, Manufactures, Agriculture, Commerce And Trade – even including an explicit reference like this:

At this period, when so much anxiety prevails respecting the fate of Sir John Franklin, everything relating to the Polar regions is of interest. The following sketch is one of the most thrilling we have ever read. (Anon., 1854)

After the search for the Franklin expedition ended, the legend rarely appeared in the press, but it never completely disappeared. Whenever the Northwest Passage is once again discussed in the press and in public today, be it in connection with its legal status, climate change or the Franklin expedition, the story of the ghost ship in the Arctic often resurfaces shortly afterwards. Even today, as historian Kenn Harper, (Reference Harper2018) noted with irritation in 2009, it is sometimes still believed to be true. Yet both the story of the ship in the Arctic and the story of Jenny are legends, but legends with a real core.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost my thanks goes to Jonathan Dore, Pender Island, British Columbia, Canada, who reminded me of the 1965 translation of the 1862 article and whose further suggestions were very helpful, not to mention the fact that he also generously took over the proofreading of this article. For giving me the idea to take a closer look at the legend of the ghost ship Jenny I have to thank Michael King Macdona, Bedford, UK. I am also grateful to Kenn Harper, Ottawa, who pointed out the similarities of Jenny’s story to that of Octavius; to Regina Koellner, Hagen, Germany, for her invaluable advice on archival materials and her help in researching newspaper archives; and last but not least to the anonymous reviewer of this article, for the helpful suggestions, that made this study far more complex than it already was.