In Harvard Yard, 500 black crosses stood stark against the white snow. Professors hurrying to class on the cold March day of 1972 could have been forgiven for assuming this was another protest against the Vietnam War, but most students knew the demonstration was different. The cross in John Harvard's hand did not represent a fallen American or Vietnamese soldier but untold numbers of dead Angolan revolutionaries, killed by Portuguese colonialists armed with Western weapons (Figure 1).Footnote 1 Fifty African Americans associated with the Boston-area Pan-African Liberation Committee (PALC) and the Harvard-Radcliffe Association of African and Afro-American Students (Afro) had placed them in neat rows to protest Harvard's refusal to sell its shares of Gulf Oil, the single largest foreign business operating in Portugal's colony.

Figure 1. The statue of John Harvard posed with one of the symbolic crosses representing Angolan dead. ©2014 The Harvard Crimson, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed with permission (Harvard University Archives).

The Gulf divestment and boycott campaign that grew from this Harvard demonstration stood out as an early manifestation of the tactics that would become pivotal to the anti-apartheid movement.Footnote 2 Sponsored by the PALC and its charismatic leader Randall Robinson, this Boston initiative took shape within a wider movement that helped cultivate a new wave of leftist black internationalism. In the 1970s, as African Americans sought to build political organizations to represent their interests, they did so in part by looking to independence struggles in Africa, particularly those active in the continent's Portuguese colonies Mozambique, Angola, and Guinea-Bissau. Facing shared problems of poverty, unjust systems of control, and political marginalization, African-descended peoples sought to establish frameworks for transnational activism that empowered their communities against racially discriminatory and exploitative economic and political systems. These shared interests provided a logic for reviving pan-African activism, while tying black Americans to the ideological and tactical agendas of socialist liberation groups that opposed U.S. institutional support for European imperialism and white supremacy. The intersection of these local, national, and international ideologies had wide ramifications for the fight against white rule in southern Africa. Gulf provided a concrete target around which the PALC built a movement, clarifying an ideology and emerging strategy for pan-African self-determination—the belief that African peoples across the globe had the right to control their communities and their resources.

The PALC, its predecessor the Southern Africa Relief Fund (SARF), and the anti-Gulf campaign occupied an important transitional moment in the history of black activism and international engagement. These efforts linked the era of Black Power with the beginning of a reenergized anti-apartheid movement, in which African Americans such as Robinson, his education-minded wife Brenda Robinson (now Randolph), and African expatriates like PALC member Christopher Nteta collaborated to challenge how the United States engaged with Africa and the wider world. Yet these two eras often occupy different territories in the public imagination and in historical scholarship. Until recently, most Americans and many academics viewed Black Power—to quote Harvard Sitkoff's widely assigned text—as “polarizing the races [and] sanctioning the cult of violence.”Footnote 3 By contrast, anti-apartheid organizing in the 1970s and 1980s provided an example of multiracial cooperation in defense of human worth—an international extension of the triumphalist narrative of the civil rights movement.Footnote 4 Despite these starkly different reputations, Black Power and anti-apartheid shared many common elements.Footnote 5 Both were campaigns for global justice that took as subjects people of African descent. Both presented a revolutionary challenge to the status quo and accepted at some level the need for revolt. Each adopted an anti-imperial ideology that demanded greater moral accountability for governments, businesses, and individuals who wittingly and unwittingly supported structures of repression and white supremacy. Most important, many of the anti-apartheid movement's African American leaders came of age during the Black Power era of militancy, and like the Robinsons drew on it when defining their beliefs, rhetoric, and tactics.

How, then, could historians have overlooked the affinities between these two efforts? Two-dimensional stereotypes about Black Power's extreme militancy have been difficult to overcome in part because of longstanding focus on groups like the Black Panthers that celebrated armed masculinity, and also because scholarly frameworks long tended to differentiate Black Power from civil rights eras.Footnote 6 Yet historians have done much over the past two decades to blur these narrative borders. They have broadened and deepened understandings of Black Power and its social impact, revealing how its participants, through the pursuit of various forms of communal self-determination, sought to transform society by dismantling white supremacy and empowering disenfranchised African Americans.Footnote 7

As participants in this movement, SARF and the PALC sought a feasible political program for black actors marginalized by a society dominated by hostile corporate interests and cautious reformers. African Americans, they asserted, needed to forcibly challenge white supremacy, yet they also hoped to do so without crossing the tripwires of state and social repression that so often hindered Black Power groups. Gulf Oil provided an ideal target for three reasons. First, its exploitative practices, both in Angola and in domestic hiring, established a clear pathway for pan-African action, while the company's support for Portugal highlighted enduring American participation in a system of global white supremacy. Second, the PALC could adopt nonviolent forms of coercion, returning to practices of civil disobedience and economic suasion legitimized by the civil rights movement. Finally, the Gulf boycott grew from nascent liberal efforts to evince solidarity with African nationalist movements through economic activism. The PALC campaign built upon this foundation, but added to it a more confrontational ideology and set of tactics that appealed to black communities deeply frustrated by the gradualism of late civil rights politics and the U.S. government approach to African decolonization. Such activism allowed for cooperation between an expanding black political class and white allies, all the while without abandoning the core values of assertive, transnational self-determination that existed at the heart of Black Power.

Recovering the activism of anti-colonial pan-Africanists such as Randall and Brenda Robinson sheds light on the still underappreciated late-twentieth-century history of black internationalism.Footnote 8 As Alvin Tillery has argued, African Americans and their leaders, given the enduring problems of racism and inequality in the United States, understandably “privilege the domestic context over the international.”Footnote 9 The PALC's Gulf campaign gained support because it defined, publicized, and ultimately legitimized a logic of pan-Africanism that made sense in the context of the concerns of many African American communities in the 1970s. Success grew from the PALC's ability to translate for domestic consumption the appeals of southern African liberation movements such as the Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (Mozambique Liberation Front, or FRELIMO) and Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola, or MPLA), whose revolutionary socialist ideology inspired, reinforced, and expanded the Black Power program. The tactics and ideology defined by the PALC—with the aid of existing institutions and the input of African nationalists—would provide a model for mobilizing African Americans during the anti-apartheid years.

As would be the case for TransAfrica and the anti-apartheid movement in the next decade, the success of the Robinsons’ PALC and the Gulf campaign came not through appeals to black solidarity alone. The PALC sought to confront the inherited power structure by building a truly mass movement, which necessitated the participation of allies beyond those in African American communities. SARF and the PALC followed liberation movements like FRELIMO in championing a universal anti-imperialism, which increasingly linked pan-African race pride with economic enfranchisement as part of an ambitious critique of a Eurocentric global capitalism personified by multinationals like Gulf. While there is not yet an accepted scholarly term that fully captures this fluid anti-imperial ideology, it perhaps fits most comfortably within tricontinentalism or, more descriptively, what Cynthia Young has termed a Third World Left. This revolutionary ideology espoused by African nationalists encouraged black Americans to define pan-Africanism as a single component in a larger internationalist solidarity challenging an unjust global system along socialist lines, which made room for cooperation with other marginalized global populations as well as more privileged allies committed to reforming traditional power relationships.Footnote 10

The PALC thus developed a specific model of leadership later adopted to great effect by TransAfrica: an exclusively black core attuned to the needs and culture of peoples of African descent, who built coalitions with white and multiracial organizations in pursuit of global justice. That the PALC's first protest of Gulf's actions in Angola took place in the mostly white—but highly scrutinized—enclave of Harvard illustrates exactly how the group balanced confrontational black activism with an ambition to engage broader audiences in critical discussions. This give-and-take across geographic, racial, and ideological divides allowed the Robinsons and the PALC to repackage the aggressive anti-imperialism central to Black Power for wider consumption, providing a road map for popularizing opposition to apartheid and American complicity.

Discovering Africa in Boston

By the end of the 1960s, an entire generation of African American activists had become disaffected with the pace of the civil rights movement. Despite a decade of struggle, their communities experienced only limited social and economic improvements—especially outside the South. As young, often well-educated blacks strove to improve conditions in the United States, they increasingly did so by looking beyond national borders. They were attracted to models of assertive black politics emerging from the extended process of decolonization and struggles to build black-majority states. Rather than adopting the Black Panthers’ symbolism of armed revolution or the incendiary rhetoric of Stokely Carmichael, both of which had invited state repression, many in this generation instead searched for ways to express their solidarity with African revolutions, and in the process spur radical change into their own communities. In Boston, this outlook inspired the PALC's predecessor, the Southern Africa Relief Fund (SARF), and its primary organizers: Randall and Brenda Robinson.

When African Americans looked abroad, South Africa loomed large. Although the solidarity activity of the African National Congress (ANC) receded after its banning in 1960, the party had achieved widespread recognition after the Sharpeville Massacre of that year, and the injustices of apartheid resonated with African Americans’ experiences with segregation in the United States. Such was the case for librarian Brenda Robinson (now Randolph), who relocated from Richmond, Virginia in 1967 so her husband could pursue a Harvard law degree. The Robinsons found race relations in Boston no less problematic than they had been in the South—from city politics to the depictions of black people in many of the books on the shelves of the predominantly white Brookline middle school library Brenda Robinson tended. After confronting the racism in the children's book Dr. Doolittle, she cathartically immersed herself in her library's sparse literature on Africa and apartheid. She felt “an immediate connection, because we [African Americans] had experienced so much of the same kind of discrimination.” Robinson had a history of civil rights activism in her native Richmond, and the relocation to Boston only amplified her desire for action. Watching as federally mandated busing took effect, and a conservative backlash rose to meet it, angry at stereotypical depictions of African peoples, and frustrated by the lack of sources on the anti-apartheid struggle, the librarian resolved to take action.Footnote 11

Her husband's intellectual journey reinforced Brenda Robinson's interests. Randall Robinson had experienced horizons wider than segregated Richmond, initially as a student at Virginia Union and during a short stint in the army, but Harvard Law School proved still more stimulating. There, he discovered the writings of Frantz Fanon and Guinea-Bissauan leader Amílcar Cabral. Stirred by the ideas of these radical philosophers, but stymied by the absence of accessible information on southern African liberation, Robinson reached out to the only readily available source on the topic—the American Committee on Africa (ACOA). Founded in the early 1950s by civil rights activists eager to link their struggle with opposition to colonialism and apartheid, the multiracial ACOA had become a clearinghouse for information on African liberation in the United States. The “reams” of pamphlets, newsletters, and ephemera sent by ACOA introduced the couple to the achievements of the continent's freedom struggles.

Most striking was the revelation of the anti-colonial wars occurring in the Lusophone African states of Mozambique, Angola, and Cabral's own Guinea-Bissau. The nationalists claimed that Portugal maintained a hold on the colonies because of military and economic aid from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the United States. Yet the revolutions were making headway in their pursuit of self-determination, establishing schools, hospitals, and cooperative stores in liberated areas. Here the Robinsons found inspiring evidence of African peoples actively resisting structural discrimination while simultaneously establishing redistributive, wholly independent societies along socialist lines.Footnote 12 Given the fact they had known so little about these developments, the Robinsons also formed critical conclusions about the limitations of traditional media, even in black communities.Footnote 13 They resolved to support the liberation movements by starting an informational campaign, linking these foreign struggles to Boston's own racial conflicts.

Harvard was no hotbed for black radicalism, but the globally recognized center for higher education attracted a mix of cultures that fed the growth of pan-African activism. With a politically conscious group of Kenyans, Tanzanians, Liberians, and other Americans, the Robinsons formed a sort of transnational salon in Cambridge, Massachusetts from which SARF emerged.Footnote 14 These unmediated cultural and informational exchanges allowed SARF to develop a unique perspective on Africa and its politics. Christopher Nteta, a South African exile attending Harvard's Divinity School, proved an especially important influence given his knowledge of conditions under apartheid and his advocacy for action in black communities. Importantly, Nteta defined liberation in terms of an anti-imperialism that transcended his homeland. He joined with the Robinsons and others in advocating for the newly founded SARF to adopt a regional, rather than purely South African, focus that would allow for a broad critique of European imperialism and foreign capitalist penetration of Africa.Footnote 15 It was not long before their emphasis shifted to the Portuguese colonies, where nationalist parties such as FRELIMO in Mozambique and the MPLA in Angola were actively engaged in military and social revolutions.Footnote 16

The Southern Africa Relief Fund and Local Pan-African Activism

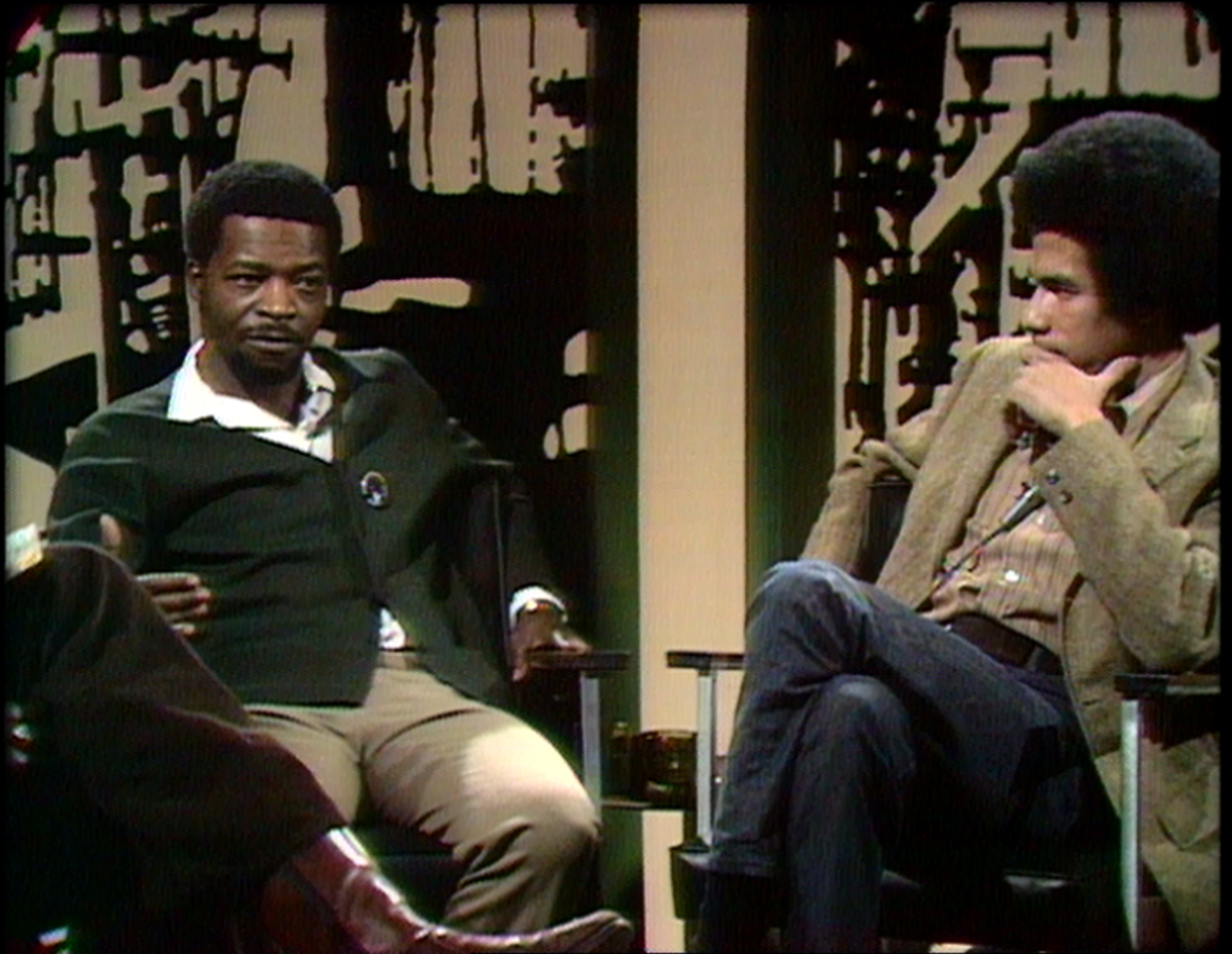

Following SARF's founding in late 1969, its members aimed to raise money “to demonstrate the spirit of Pan African solidarity” and to encourage “the political, economic, and diplomatic disengagement of the U.S. from minority rule regimes in Southern Africa.” They defined this region as states under imperial and minority rule including Angola, Mozambique, Rhodesia/Zimbabwe, South Africa, South West Africa/Namibia, and—revealing a geographic flexibility born of a commitment to Lusophone liberation—Portugal's west African colony Guinea-Bissau. They donated the funds they raised to the Organization of African Unity to help care for refugees of liberation struggles in frontline countries such as Tanzania. SARF also hoped to provide “badly needed” information on the revolutions that received no coverage in mainstream papers, white or black (Figure 2).Footnote 17 SARF's founders not only wanted to change U.S. policy; they also sincerely believed that international events would affect African Americans. “We must be able to understand the globally coordinated design of our oppression as Africans,” Robinson wrote for the national periodical Black World, “and act accordingly.”Footnote 18

Figure 2. Chris Nteta (left) and Randall Robinson (right) represent SARF in a discussion on southern Africa with John Slade for WGBH's Say Brother, a local program concerned with African American issues. Robinson was especially comfortable with the media and emerged as the most visible face of SARF and the PALC. ©WGBH/Courtesy of the WGBH Media Library and Archives.

With the encouragement of Nteta and others, these middle-class revolutionaries understood their struggle not only as an effort to forge connections to Africa, but also as part of a global revolution in favor of radical economic reform, which linked peoples of various races against a common exploitative international capitalism. As a result, SARF's specific form of pan-Africanism was not one of strict racial nationalism. It centered upon the rejection of traditional forms of external exploitation, a shared struggle against Euro-American domination, and the implementation of non-dogmatic notions of communalism. It owed much to African nationalists like Cabral and the leaders of FRELIMO, who merged identity politics and socialist anti-imperialism into a more inclusive Third World Leftist ideology and who viewed racial politics alone as simplistic and potentially divisive.Footnote 19 To be sure, SARF intended, in Randall Robinson's words, to encourage blacks to “see ourselves, wherever we live, as Africans equally responsible for the liberation of our brothers wherever they live.” Yet in defining black liberation from the “white Western industrial powers” and the “Western profit-worship community,” the Robinsons and SARF incorporated within their pan-African perspective a deeper critique of an economic system that promoted race as a way of defining the free and unfree, the wealthy and the impoverished.Footnote 20 This train of logic allowed SARF to delineate a hierarchy of solidarity that placed emphasis on black organizing without abandoning opportunities for multiethnic cooperation on the outskirts of a racially defined core. This complex and fluid anti-imperial ideology provided a framework for understanding how activities undertaken in the United States would support African liberation, and how foreign strategies might successfully be replicated in the American context.

SARF attempted to convince African Americans that problems in Africa and U.S. cities like Boston were interconnected—that Africa mattered deeply in the midst of the Vietnam era. While the group launched a national fundraising campaign, Brenda Robinson assembled a slide show on imperialism and apartheid, which SARF presented to local schools, community organizations, and regional gatherings. Often accompanied by the personal reflections of Nteta, the performance compelled audiences to confront American complicity with the continuation of minority governance.Footnote 21 SARF did not confine its efforts to black communities—presenting in some majority white schools—but the campaign had distinctly pan-African considerations in mind. As Randall Robinson explained, “We must provide our people with informational materials demonstrating the relationship of our oppression to that of our brothers living in the homeland.”Footnote 22 SARF and its members thus shared a mission with the wider movement for African nationalist education that historian Russell Rickford has argued helped transform black consciousness, albeit without fully ascribing to the “internal colony” rhetoric that sometimes fed exclusionary, separatist politics.Footnote 23

That African Americans could not demand independence from a colonial master did not mean they could not resist injustice. SARF believed “the same powers that oppress us [in the United States] are involved in oppression everywhere in the world.”Footnote 24 Understanding the struggles of southern Africa became a way of shining a light on the forces behind inequality in the United States, Latin America, and other regions. The first mental step toward local self-determination and “strengthen[ing] the international African community,” they contended, required identifying and supporting the work of African revolutionaries.Footnote 25 In emphasizing pan-African connections, SARF helped reignite attention to southern Africa among radical youth while also reinforcing and mediating the work of predominantly white organizations, including the radical Boston-based Africa Research Group and the traditionally liberal ACOA, which had struggled to make headway in many black communities.Footnote 26 SARF communicated international problems as pertinent to the immediate context of African American communities in a way existing institutions had not.

By forging this relationship between local activism and global issues, SARF and its successor, the PALC, made their greatest contributions. The group's initial appeals for funds brought positive responses from local figures such as Harvard Law Dean Derek Bok and organizer Mel King as well as national leaders like A. Philip Randolph.Footnote 27 Their grassroots, participatory approach was not universally well received. The pioneering African American diplomat and United Nations (UN) official Ralph Bunche worried that independent SARF, however laudable its goals, might distract from established funds, including the UN Trust Fund for South Africa. Bunche concluded that “this dispersion of efforts may be counterproductive.”Footnote 28 He was likely correct from the standpoint of fundraising; SARF lacked resources and had little experience handling donations. However, he misunderstood the essential mission of the organization. More important than raising money was the ability to raise awareness of issues facing southern Africa, link them to local racial inequities in cities such as Boston, and demonstrate the role that a mobilized black public could play in shaping U.S. policy abroad and at home.

Just how difficult such organizing could be was illustrated by the first major campaign in this self-consciously transnational vein: an action against the Cambridge-based Polaroid Corporation. A few months after the Robinsons launched SARF, two employees at the film giant—Caroline Hunter and Ken Williams—decided to protest Polaroid's sale of equipment to make ID cards to South Africa. They also objected to the company's practice of paying its African American employees markedly less than white coworkers.Footnote 29 Hunter and Williams collapsed the distance between southern Africa and the United States, arguing that Polaroid's policies represented a consistent disrespect for the rights of black peoples.Footnote 30 Dubbing themselves the Polaroid Revolutionary Workers Movement (PRWM), the pair looked to the wider public to exert economic pressure on the company.

Following the advice of SARF member Chris Nteta, the PRWM expanded its demands to include not only the company's disengagement from South Africa and its public renunciation of apartheid (both domestically and abroad), but also that Polaroid donate any profits acquired in the Afrikaner state to liberation movements. They launched a boycott aimed at all “right-on thinking people,” and posters soon appeared throughout the city, gathering support from Harvard students and others.Footnote 31 The movement garnered national and international attention from ACOA, the British Anti-Apartheid Movement, and black members of Congress, including Charles Diggs (D-MI) and Ronald Dellums (D-CA). Williams resigned and Hunter eventually received a pink slip, but Polaroid also felt obliged to publish a defensive article in local newspapers, admitting it did not know how to respond to apartheid despite the fact that its South African profits were equivalent to those of a “big American department store.”Footnote 32 Moreover, Polaroid implemented new labor polices at its South African subsidiary and made a generous donation to the Boston-area United Black Appeal.Footnote 33 The boycott weakened thereafter, but nevertheless, the PWRM had demonstrated that there was a concrete and growing interest in confronting transnational racial exploitation. The PRWM thus became a model for activism in Boston's black community.

However, certain circumstances limited the PRWM's ability to build a long-lasting movement. SARF, for example, had supported the Polaroid boycott through its informational activities and Nteta's role in advising the group, but the Robinsons felt that their efforts fell short in aiding the southern African revolutions. Polaroid was not the only company selling ID technology, nor would its potential exit from South Africa cause real economic hardship for minority governments. The Robinsons’ frustration echoed that of other internationally minded blacks in Boston and elsewhere. The influential leftist Amílcar Cabral, leader of the FRELIMO and the MPLA-aligned Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cabo Verde, or PAIGC), had urged international supporters to find their own forms of resistance to global imperialism based on local contexts.Footnote 34 The members of SARF embraced this call to action and affinity with African liberation, yet it remained unclear what African American action, beyond boycotting firms like Polaroid, might look like. African Americans’ minority position within the United States constrained many potential avenues, both democratic and revolutionary. Quoting Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton, John Clark writing for the Harvard-Radcliffe Afro asked with characteristic frustration: “When black people in Africa begin to storm Johannesburg, what will be the role … of black people here?”Footnote 35

The Robinsons hoped to find an answer by directly consulting with African revolutionaries. After Randall Robinson completed his degree, the couple traveled to Tanzania in July 1970. President Julius Nyerere had established what they considered the model of an African socialist state on the policy of ujamaa, or cooperative economic development.Footnote 36 Tanzania's capital, Dar es Salaam, also beckoned as the center of black liberation. With Nyerere's backing, each of the major liberation organizations maintained an office in Dar, including Mozambique's FRELIMO—the most Western-friendly of the liberation movements. The party's late president, Eduardo Mondlane, had built an extensive network of allies in the U.S. northeast that included the New York–based ACOA, and stationed a permanent party representative to the UN, Sharfudine Khan.Footnote 37 New president Samora Machel maintained his predecessor's commitment to cultivating relationships with civil society groups in North America and Europe, even as the party strengthened its leftist identity under his leadership. During his six month residence, Randall Robinson made contact with FRELIMO and other liberation groups that likely advised him on how to aid the nationalist cause. By the time the Robinsons returned to the United States, they had found a focus for their activism—one that dovetailed with a longtime FRELIMO concern: the intrusion of American capital into the colonies.Footnote 38

The Pan-African Liberation Committee and Radical Solidarity

SARF's initial approach had focused on educating audiences about the humanitarian crisis in Africa, emphasizing the tragedy of apartheid and colonialism and urging contributions to relief efforts. But these had been half measures to the Robinsons, Nteta, and their allies, who desired ways to more directly aid the liberation struggles. Back in Boston in 1971, the Robinsons moved in more radical directions than they had before, zeroing in on opposing American institutions backing Portugal and South Africa while raising funds for liberation groups with no strings attached. The core of SARF—the Robinsons, Nteta, and Harvard law students Jim Winston and Robert Holmes—formed a second organization, the Pan-African Liberation Committee (PALC), which embraced a radical pan-African rhetoric echoing the larger leftist anti-imperialism promoted by FRELIMO and other socialist parties.Footnote 39 Nteta explained that the PALC had formed to oppose “American businesses … in Angola, Mozambique, Guinea Bissau, and Latin America [that] are playing a very reactionary and counterrevolutionary role—supplying engines of war through NATO … and the sinew and economic muscle to enable these forces of darkness to keep a people in thralldom.”Footnote 40

Like the PRWM before it, the PALC established a broad economic critique of amoral, unrestrained capitalism as the centerpiece of its anti-imperial agitation—linking the economic frustrations of African Americans to the subjugation of all people under imperial yokes. The PALC did not limit itself to the problems of one state or the complicity of one corporation: it took aim at all of the 260 and more businesses that cooperated with the systemic exploitation of African peoples, many of which also operated in Asia, Latin America, and the United States.Footnote 41 This would be the African American contribution to the liberation struggles. As Robinson explained shortly after the PALC's formation to a curious Representative Charles Diggs, the Democratic chairman of the House Subcommittee on Africa, “If Black people are to prevail in a free Africa, Afro-Americans must play a key role in facilitating the economic, political, and diplomatic disengagement of the United States.”Footnote 42

As radical as the agenda may have been, the PALC's tactics proved more constrained. Its well-educated members studiously sought to avoid the stereotypical image and fate of groups such as the Black Panthers. By 1970, the Panthers had embraced anti-imperialism and had begun constructing multiracial fronts, but they struggled to arrest the party's decline. Their initial public displays of armed self-defense—which superficially resembled African revolutions—played well with disaffected urban youth but had alienated many cautious African Americans and invited unwanted attention from the government. The Nixon administration conducted covert campaigns against the Panthers and other Black Power groups aligned with African liberation, while quietly embracing the white minority regimes on the continent as valuable pro-Western allies.Footnote 43 Randolph recalls that this hostile environment led SARF to moderate its initial goal of directly supporting the liberation struggles, especially after advice by Tanzania's UN Representative Akili Danieli to “stay out of trouble with your government.”Footnote 44 The PALC sought a set of tactics that could achieve its ambitious goals without alienating potential allies or inviting damaging attention from the entrenched power structures that had quieted the Panthers and the PRWM.

The PALC's solution merged the revolutionary action promoted by Portuguese African nationalists with older forms of domestic protest. Both FRELIMO and Cabral's PAIGC operated armed campaigns but downplayed armed revolt in favor of two elements more vital to successful revolutions: party-building and education.Footnote 45 These two important activities seemed feasible in the context of the United States, and both had been pivotal to earlier civil rights activism. Cabral's widely read philosophy argued that both actions began with the “class suicide” of the leadership, in which educated, privileged blacks abandoned their claims to a separate culture and lifestyle in order to unify with the common people living under the harshest oppression.Footnote 46 Randall Robinson followed this path, working at a Roxbury nonprofit while continuing his solidarity work, and the pursuit of a cross-class accord became one element of the PALC's organizing. In the waning years of the Black Power era, which many historians have criticized for failing to produce a truly mass politics, Robinson and the PALC attempted to do just that, using a transnational economic campaign against the racial status quo that brought black followers together under the umbrella of pan-African anti-imperialism.Footnote 47

Knowing that similar tactics had worked for the civil rights movement, the PALC seized an opportunity for action presented by a campaign launched by a number of Protestant churches. Beginning in the late 1960s, the United Presbyterian Church's Task Force on Southern Africa, along with other religious leaders, had agitated for more responsible corporate practices in the region primarily through the use of stockholder activism. Initial targets included Gulf Oil, Exxon, IBM, and General Motors. They used their role as sizeable shareholders to introduce resolutions to annual board meetings, hoping to win enough support from fellow stockholders to shift corporate policies away from complicity with the southern African regimes. Various initiatives related to the Vietnam War, discriminatory hiring practices, and South Africa had garnered attention, but the churches found that even with millions supporting their efforts, they often fell far short of commanding enough votes to sway boards dedicated to profit-minded definitions of corporate responsibility. As chair of the House subcommittee, Congressman Charles Diggs sought to elevate political attention to the problem of southern Africa in 1971 by holding hearings on the role of American businesses in southern Africa. He contacted ranking management in the United States, but to little avail. Most businesses were uninterested in sharing details of their operations in Africa, and even Diggs's congressional colleagues critical of U.S. foreign policy in the Third World remained largely indifferent.Footnote 48 Both the congressman and the churches faced a similar problem as they sought to change policy; the mass of protesters who had risen against the Vietnam War generally had little yet to say on southern Africa.

A grassroots movement needed to rally popular attention to southern Africa, but hearings and elite shareholder activism did not engage the average citizen. Boycotts and divestment activism had not initially been a goal of either Diggs or the churches, but soon ACOA and young leftists associated with the religious bodies along with members of the PALC grew increasingly interested in their potential. The strategy of merging mass tactics with the push for institutional divestment and individual boycott had the advantage of placing multiple levels of pressure on economic backers of Portuguese colonialism and apartheid, while aiding both the churches and Diggs as they sought to persuade business and political leaders. The PALC recognized that the vagaries of public attention required activists to concentrate their efforts on a single, widely recognizable target in order to achieve maximum participation and visibility. From the more than 260 American corporations operating in southern Africa, they chose Gulf Oil, the single largest American investor in the Portuguese colonies.Footnote 49

Occupy Gulf Oil

The Gulf campaign pitted liberation priorities against an identifiable institution. The oil giant had been the corporate nemesis of the Portuguese African nationalist movements since it first arranged exploration rights in Angola and Mozambique in 1964. FRELIMO regularly attacked the company, arguing that its expertise and capital helped prop up a weak colonial dictatorship.Footnote 50 Payments to the Lisbon government for drilling rights and—after 1968—royalties from oil produced in Angola funded Portugal's three active colonial wars, which by the early 1970s ate up almost half of the state's annual budget. The $61 million that Gulf paid Portugal in 1972 amounted to almost 60 percent of military expenditures for that year in Angola alone.Footnote 51 Given this dependence, FRELIMO argued that the loss of oil revenue would strike a major blow to the Portuguese war machine. For U.S. activists, the company illustrated in easily understandable terms the economic linkages that tied domestic consumer decisions to foreign wars.

Gulf provided an especially useful target in the Boston-Cambridge area, since Harvard stood as the largest academic investor in the company, holding more than 650,000 shares worth roughly $15.4 million. In 1971, the United Presbyterian Church urged the university along with other company stockholders to mandate that the company study the Angola situation, increase the size of the board, and end its activities in all colonial areas. Harvard rejected the proposal, backing management along with all but one of the six hundred universities, ten banks, and several mutual funds approached by the church. Such setbacks had been common in the two years that the Presbyterians, the United Church of Christ, ACOA, and a coalition of youth activists had cooperated on the campaign against Gulf's activities in Angola. Organizing had proven difficult owing to the national preoccupation with Vietnam and a suspicion within African American communities of the predominantly white organizers.Footnote 52 Nonetheless, the PALC saw an opportunity even in Harvard's rejection of the Presbyterian overture.

The PALC began a patient confrontation with Harvard. It made little headway at first. In the fall of 1971, the PALC publicly challenged the university to revisit the ethical foundations of its investment policies. It argued that a decision to divest from Gulf, a public statement explaining the logic, and a promise to pursue similar actions against other corporations “would be a meaningful act in support of freedom and self-determination for people everywhere.”Footnote 53 New President Derek C. Bok—who knew Randall Robinson while dean of the Law School and had contributed to SARF—signaled that his administration might be more open to considering such proposals than its predecessor, but he effectively tabled the request by promising to research the issue. The PALC agitated for an answer, but a meeting with the board of visitors in April 1972 proved no more fruitful.Footnote 54

But publicity surrounding the issue helped Robinson's committee strengthen and expand relations with local and national organizations, notably the newly formed Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) led by Diggs, Boston's Africa Research Group, and the Harvard-Radcliffe Afro, which joined the PALC in occupying Bok's office in February 1972. Many organizations sympathetic to African revolutions but unsure about how to act found an opportunity in the Gulf campaign. The Association of Black Faculty, Fellows and Administrators and the Harvard Crimson both backed the PALC, with the Crimson opining that, “In 1972 it is not shooting the moon to ask men of goodwill to do their best to put an end to the bloody remnants of the 19th century.”Footnote 55

In response to the pressure, Bok publicly acknowledged reports about the poor treatment of Africans in the Portuguese colonies. But he contended that taking action against Gulf would not touch the oil company's bottom line; it would merely cost the university hundreds of thousands of dollars in payments to brokers.Footnote 56 Bok affirmed his and the board's responsibility for the fiscal health of the university over any engagement with issues of international justice, no matter personal feelings on the matter.Footnote 57

The PALC and Afro offered a rejoinder to the administration and its “morally bankrupt” position.Footnote 58 In early March, the committees planted symbolic black crosses in the center of Harvard Yard. Ten days later, the PALC hosted MPLA representative Abel Guimarães alongside activist Robert Van Lierop (recently returned from a trip with FRELIMO behind the lines into Mozambique), who argued that Harvard faced a moral crossroads. If the university chose to divest, others might well follow and convince the oil giant to reassess its position in Angola. They rejected the claim that divestment would mean little to the liberation movements, because pressuring Gulf out of Angola would seriously affect Portugal's war making capabilities.Footnote 59 For concerned African Americans, ethical responsibilities outweighed the threat of financial losses. And action on divestment had the potential to catalyze popular engagement with southern African issues more broadly. Therefore, when Diggs and the CBC came to Harvard in early April to discuss priorities for its national agenda, they surprised their hosts by joining PALC members in condemning Harvard, an indifferent media, and “corporate investments [that] strengthen white regimes.”Footnote 60 “There is no middle ground,” the PALC argued provocatively at a joint press conference with the CBC; “blood must flow in the Portuguese colonies. How much blood must flow can only be determined by Harvard University and institutions like Harvard.”Footnote 61

As its support grew, the PALC intensified the campaign. Pushed in part by the youthful energy of the Afro and by public support from its congressional allies, the two groups issued an ultimatum to Bok on April 17: divest or face escalation. “Each day Gulf's Cabinda operation brings revenue for the Portuguese war effort. Each day means more lives of Africans lost in the war for liberation.”Footnote 62 Two days later Bok responded that Harvard would not divest. Within fourteen hours, more than two dozen African American students along with Winston and Randall Robinson occupied Massachusetts Hall in the heart of campus.Footnote 63 Making clear the commonalities between foreign and local struggles for self-determination and communal control, the groups demanded the immediate sale of Harvard's stocks and the investment of those proceeds in Cambridge poverty programs. “We propose,” Robinson explained at a press conference, “that Harvard invest in life rather than death, and that they actively promote the creation of a new society at home rather than the destruction of an old and rich one in Africa.”Footnote 64 With the occupation, the PALC advertised its ambitious critique of the racially discriminatory global economic system in a single symbolic action.

The weeklong protest sparked more organizing and grabbed national headlines. A multiracial crowd appeared in support of the protest almost immediately and grew in the following days as more people came from nearby communities and universities. The crowd at times numbered nearly 1,000 and chants of “U.S. out of Southeast Asia, Harvard out of Gulf” chased freshman from their dorms, while the occupants of Massachusetts Hall took turns distributing anti-Gulf literature through the windows and quietly studying in corners (Figure 3).Footnote 65 The national press took note. New York Times commentator Jeff Greenfield, for example, cited the PALC as among the first university movements to demand divestment, identifying the action as a new front in the movement for social responsibility.Footnote 66 The occupation merged with a new wave of popular protests against Vietnam, and pushed Angola onto the national radical agenda.Footnote 67 A group of predominantly white local activists even launched their own complementary campaign after Robinson expressed a desire to keep the pan-African leadership of the committee undiluted, forming the Boston Gulf Boycott Coalition, which would later become one of the city's most active anti-apartheid groups.Footnote 68 The occupation ended only when the university threatened police action and the residents of Massachusetts Hall decided that their arrests would serve little purpose. The student occupants exited to the cheers of nearly 1,500 supporters (Figure 4).Footnote 69

Figure 3. WGBH documented the expansion of support for the PALC's campaign, from an early picket outside the Portuguese consulate to the solidarity marches in Harvard Yard. A press conference accompanying the occupation confirmed the links between the PALC, Afro, and the wider Boston community, providing an opportunity for MIT political science professor Willard Johnson and organizers of the upcoming African Liberation Day to express opposition to Gulf and Portuguese colonialism. ©WGBH/Courtesy WGBH Media Library and Archives. http://openvault.wgbh.org/catalog/V_ADE6DD8B0FB445E886D09C0AF1FEEDDE

Figure 4. With police looking on, members of the PALC and Afro defiantly exited Massachusetts Hall after the week-long occupation. Roughly 300 supporters cheered as the occupiers rallied at the Harvard statue—now dressed in the white sheet of the Ku Klux Klan and again holding a black cross—then led a march into Cambridge while jeering the neighborhood Gulf station. This photo ran in national publications such as Newsweek. Photograph: Ira A. Burnim, ©2014 The Harvard Crimson, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed with permission (Harvard University Archives).

Harvard still refused to sell its Gulf stock, but a chastened Bok proposed after the occupation to leverage the university's position as an investor to “strongly influence Gulf to use its power to aid the lot of the Angolese people.” Gulf management promised to publish information on the oil company's activities in Angola, as well as plans “for improving job opportunities, training, and other benefits for black Angolans.”Footnote 70 In a similar break with tradition, the Harvard Corporation cast an unprecedented vote in favor of church resolutions demanding that General Motors and Ford disclose information on minority hiring and operations in South Africa shortly after the occupation ended.Footnote 71 Yet these measures failed to fully address PALC demands. The renegade occupants of Massachusetts Hall did not request that Gulf treat its few black Angolan employees as if they had the civil status of oil workers in Mississippi. Gulf had to end its association with an unjust regime that denied African peoples their human rights. The PALC called for businesses—and in particular nonprofit institutions like Harvard—to place matters of life and justice above the bottom line.

The liberal Bok genuinely considered Harvard's steps an ethical response to unrestrained capitalism. In explaining his decision, he mirrored Polaroid, claiming it would be “self-indulgent and immoral … [to] turn our back upon the problems of the world” rather than “take a positive step to alleviate the problems of those who suffer from unjust government policies.”Footnote 72 Bok's unintentional anticipation of the Reagan-era policy of constructive engagement sidestepped the fact that the United States and Harvard itself had yet to come to terms with the problems of domestic inequality that had driven the PALC to find common cause with foreign liberation groups in the first place (Figure 5). But Randall Robinson remained hopeful. “PALC began last fall with four people who went to see President Bok,” he proclaimed confidently. “Four have become 2,000, which will become 20,000. This will spread across the land.”Footnote 73

Figure 5. Demonstrations continued during the semester, encouraged by the university's half-hearted attempts to discipline the occupiers of Massachusetts Hall. In May, the PALC and Afro joined with prominent community leaders to protest the disciplinary hearings and continue to press for divestment. ©2014 The Harvard Crimson, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed with permission (Harvard University Archives).

The Gulf Boycott Goes National

The Harvard action propelled Gulf into the national spotlight. The attack on the multinational corporation struck all the right chords with Americans looking to act on a variety of contemporary issues: highlighting a less objectionable if no less insurrectionary side of Black Power, revealing corporate greed, and demanding relatively benign action on the clearly problematic issues of colonialism and racial discrimination. The nation's largest newspapers devoted space to the Massachusetts Hall occupation, while black columnists attacked Harvard for “soil[ing] its hands with dirty silver from a sordid temple.”Footnote 74 African Americans were particularly responsive because of Gulf's discriminatory domestic hiring practices.Footnote 75 The CBC agreed to distribute committee writings through its syndicated column and consulted Randall Robinson on its African foreign policy priorities. Gulf's monetary importance to Portugal and the connection of oil companies with more general issues of social and environmental justice also made the campaign an ideal introduction to the southern African cause for a broad array of activists. National figures embraced the PALC and its model of transnational activism, in part because the Oxford-shirt wearing agitators wrapped their radical anti-imperial politics in a self-consciously respectable, Harvard-trained package.Footnote 76 As the PALC, ACOA, and other groups set their sights on a nationwide mass movement, their focus of action began to shift from divestment to a mass boycott. They would mobilize and unify African Americans and link them with radicals and southern African activists by providing a clear-cut, widely recognized symbol for opposition: Gulf.

PALC's participation in the first African Liberation Day (ALD) in 1972 helped launch its new direction. This national celebration revealed the evolution of Black Power ideology in the 1970s as adherents began to emphasize more ambitious forms of political organization as well as institution and alliance building. The initiative was guided by the head of Malcolm X Liberation University, Owusu Sadaukai (Howard Fuller), who, like the Robinsons, had visited Tanzania, where FRELIMO's leadership urged him to mobilize popular opinion against Portugal in the United States by explaining the revolution to the American people, who could then demand changes to U.S. policy through democratic processes.Footnote 77 Using the network he had developed while founding the university—including ties to the Harvard Afro—Sadaukai assembled a broad coalition of Black Power and civil rights groups.Footnote 78 On the revolutionary side were such figures as Amiri Baraka and his nationwide Congress of Afrikan People (CAP), along with Black Panthers Huey P. Newton and Angela Davis. Representing the older guard were, among others, Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) head Ralph Abernathy and four congressmen including Diggs. Occupying the space in between were those like the Robinsons, Jim Winston, and the PALC, whose ideology aligned them with Black Power but whose buttoned-up style and careful tactics had the support of moderate elites.Footnote 79

As ALD approached, the search for unity received a boost by the National Black Political Convention (NBPC) in Gary, Indiana, which brought together many of the same actors. After sometimes contentious negotiations, the convention's National Black Political Agenda established a framework for transforming a society founded on “white racism and white capitalism,” including demands for greater protection of basic rights, the development of black-run economic institutions, and self-determination for Washington, D.C.Footnote 80 The document formalized the domestic goals of the ALD's program and closely paralleled much of the PALC's motivating ideology, demonstrating the extent to which African American political leaders had begun to unite around key elements of the Black Power anti-imperialism that motivated the Gulf campaign.

Where both ALD organizers and the PALC went further was in urging the creation of a transnational coalition of black people. As one editorial explained, the ALD stood against the “thinking patterns of the black community” that saw the world “only in terms of the local and the immediate, and only in terms of pieces of the whole.”Footnote 81 ALD organizers shared the PALC's belief that global inequality was linked along questions of race, economics, and politics. The liberation of Africa could undermine the stereotypical depictions of black peoples that burdened the African American community. A nationwide ALD celebration might convince many African Americans that their full equality related directly to freedom on the African continent.

ALD organizers intended to gather African Americans together in San Francisco, Toronto, and Antigua, but Washington, D.C. would be the primary location. Taking note of the recent battle at Harvard, they pledged solidarity with the PALC and the Afro and adopted the Gulf campaign as one of their primary causes. On May 27, 1972, the first ALD attracted over ten thousand people to Washington, including a few busloads from Boston. The protesters assembled on the National Mall (renamed Lumumba Park for the festivities) after a march through the city that stopped at the State Department, the Portuguese and South African embassies, and the Rhodesian information office. Speaking before a crowd that friendly estimates placed around 25,000 people, Sadaukai lambasted the U.S. government for its continued support of Portugal, while singling out the Gulf Corporation as an example of equally odious business practices. He urged attendees at the rally to boycott Gulf stations, and led an echoing chant of “We are an African people.”Footnote 82 Other supporters joined Sadaukai in identifying the oil boycott as the most important “positive action steps for the Black community that can give concrete substance to our support” after the marches ended.Footnote 83 The mass rallies solidified the emerging Gulf boycott as the solidarity action of African American radicals in the 1970s, legitimizing the PALC's tactics of economic coercion as a new front in the assertion of Black Power.Footnote 84

After the success of the ALD, Sadaukai formalized the ad-hoc organizers into the African Liberation Support Committee (ALSC), providing an infrastructure to nationalize the Gulf campaign. As the ALSC prepared to sponsor more rallies the coming year, it proposed the establishment of numerous committees across the country to maintain solidarity action in the meantime. The ongoing efforts impressed leaders of Africa's liberation movements, and the MPLA actively encouraged its allies to “expose and demonstrate against Gulf Oil's investments in Angola.”Footnote 85

Randall Robinson, who emerged as a prominent member of the ALSC national board, developed a strategy in anticipation of ALD 1973 that targeted a handful of states with Gulf franchises and large black populations.Footnote 86 Seven of Gulf's top-ten most lucrative markets had black populations above 10 percent, with some like North Carolina and Georgia coming closer to one-quarter of the populations.Footnote 87 As Robinson explained optimistically to Congressman Diggs, also a member of the ALSC coalition, “If in the key states we can win overwhelming Black support in addition to marginal support from whites, Gulf's profit margin can be substantially reduced.”Footnote 88 Local ALSC chapters coordinated the widespread effort, though Robinson also sought funding from churches and liberal foundations with ties to ACOA.Footnote 89 The PALC launched the national campaign by “calling on all Black people and others who believe in freedom to boycott the products of the Gulf Oil Company.”Footnote 90

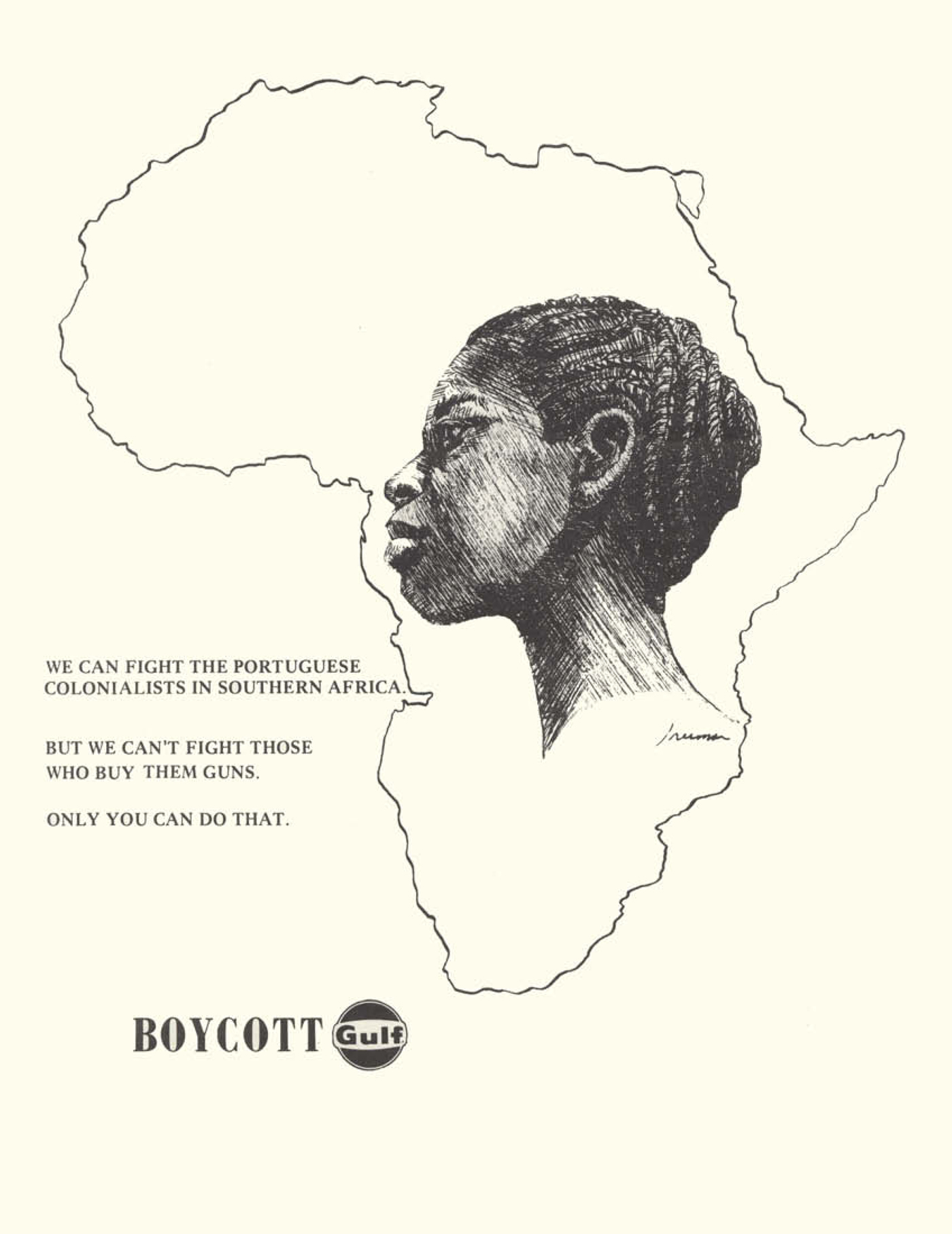

Robinson designed the boycott for maximum economic effect, but the primary purpose of the campaign remained the traditional PALC goals of informing and organizing.Footnote 91 In the months leading up to the national ALD celebrations of May 1973, the ALSC launched a major national effort, with PALC associates coordinating activities in twenty states. While it is difficult to identify the specific members of PALC's growing web of supporters, many likely came from backgrounds similar to the well-educated Robinsons and their colleagues. Most had ties to local ALD organizers or Baraka's CAP, and they understood their actions as contributions to building a mass political movement. In April, these individuals distributed a “flood” of bumper stickers, posters, and foldouts from Florida to Washington state, dramatizing Gulf's role in bankrolling Portugal's wars.Footnote 92 On one leaflet, an image of a noble African face situated on a line-drawn continent roughly between Mozambique and Angola provided a subdued image of revolutionary dignity, while the inscription urged action: “We can fight the Portuguese colonialists in Southern Africa, but we can't fight those who buy them guns. Only you can do that” (Figure 6).Footnote 93 Placed with little fanfare in public gathering spots, the leaflets and posters gave PALC confidence that they “alone will raise initial questions, comments, and concern.”Footnote 94 The campaign depended on local organizations to answer these questions and direct popular concern by working with influential institutions such as churches, community centers, and schools. This decentralized structure personalized appeals in a way that national organizations like ACOA had never been able to accomplish.

Figure 6. Flyer distributed by the PALC. Republished with the permission of Brenda Randolph (Michigan State University Libraries Special Collections).

The results were impressive. In Florida alone, the Gulf Boycott coordinator distributed 2,000 posters in two weeks across the state, with special emphasis on cities near universities and the capital city of Tallahassee—clearly aiming to link black internationalism with student radicalism. Churches and community organizations opened their doors to anti-Gulf speeches, and local radio and television stations allowed for a once-a-week news spot devoted to Gulf campaigning. In New York City, the PALC representative covered subways with more than 2,500 posters and handed out informational booklets at the local celebration of African Liberation Day in 1973. Through Diggs, the PALC also assembled dozens of black celebrities and officials who lent their names to the campaign.Footnote 95 The expansive list of luminaries, ranging from Harold Cruse, C. L. R. James, and John Henrik Clarke, to Fannie Lou Hamer, Jesse Jackson, Ossie Davis, and famed black journalist Ethel Payne, appeared on full page advertisements in Jet and Ebony declaring the Portuguese African struggle “is also our war.” Other backers included prominent politicians such as Gary, Indiana Mayor Richard Hatcher and nine congressmen including Diggs, Ronald Dellums, Parren Mitchell, John Conyers, Charles Rangel, and Andrew Young, all of whom had begun to consider action on southern Africa as valuable components of their political appeal to black voters.Footnote 96

Though they had refused to discuss Gulf's operations in Angola for much of the previous year, the oil company's spokesmen now committed to making no further investments in countries where it could not “be an equal opportunity employer.”Footnote 97 As at Harvard, the PALC and its allies rejected such half-measures and continued the campaign, but the corporate policy shift attested to the power of the boycott. Upping the ante, the PALC coordinated pickets aimed at publicizing the Gulf Boycott in more than twenty-five cities that September.Footnote 98 The PALC-led coalition aimed to put real economic pressure on Portugal, but even more immediately to augment and diversify the base of black solidarity.

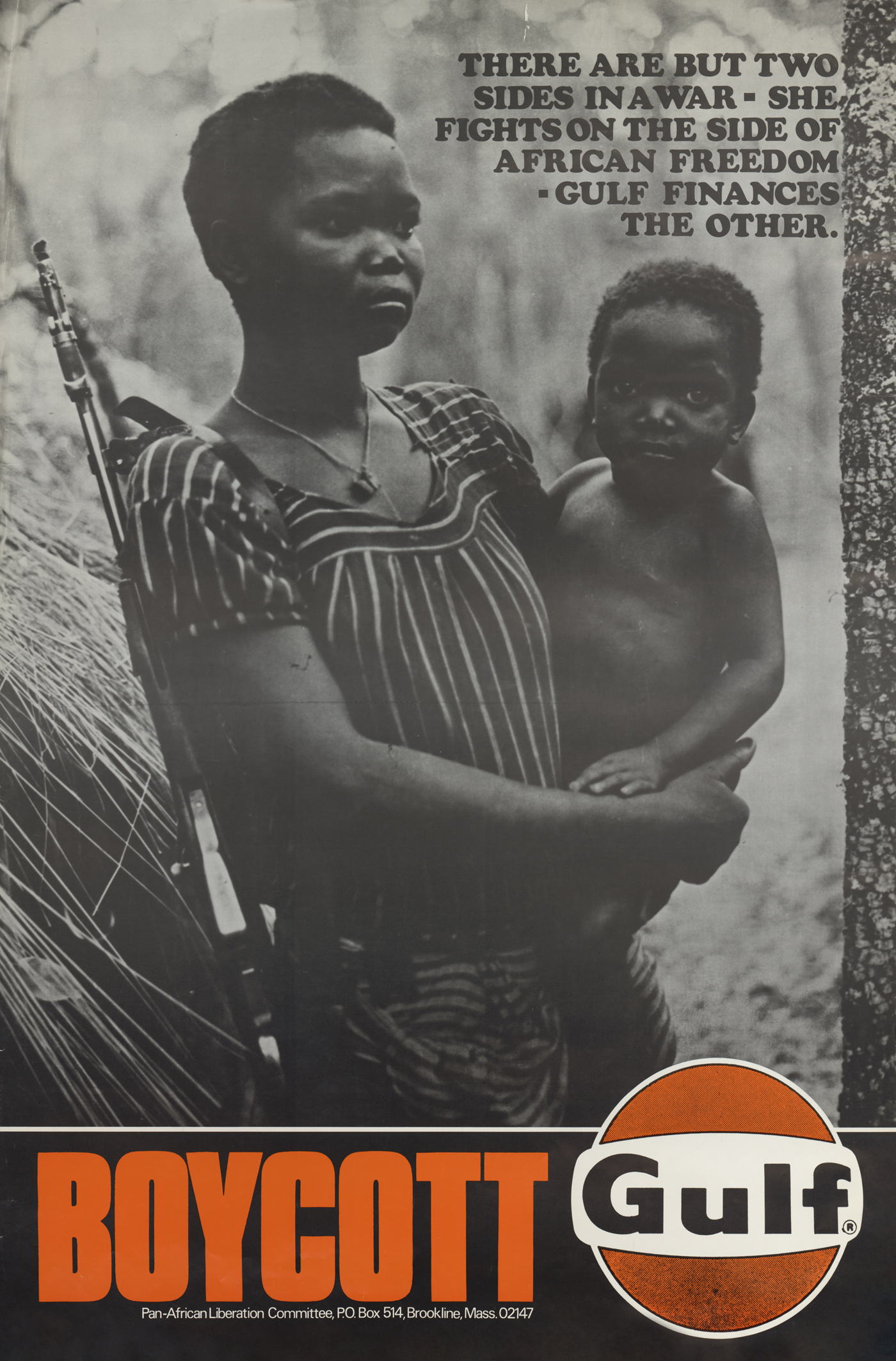

Pan-Africanism lay at the heart of the PALC appeal, but Nteta and Robinson refused to limit themselves to working only within black communities. The PALC reached out to predominantly white organizations like ACOA and the religiously associated Gulf Boycott Coalition (GBC), hoping to take advantage of any and all parties interested in PALC's goals of mobilizing people and distributing information.Footnote 99 Given the GBC's parallel interest in Gulf and the committee's early work organizing gas station–specific boycotts in Ohio, Robinson believed “we can learn a lot from their experience.”Footnote 100 In cities where interracial activist relations were good, such as in St. Louis, New York, and Atlanta, informational exchanges turned into cooperation as the PALC and the GBC united in attacking Gulf.Footnote 101 Still, Robinson remained aware of his different audiences. He sensed that most African Americans more quickly grasped the problem of colonialism in Portuguese Africa and how it related to their own economic circumstances in a highly unequal system (Figure 7). But he assumed that whites required more convincing. He recommended to local contacts that shocking “atrocity” posters be concentrated in predominantly white areas, as less sympathetic viewers needed first to confront the “biting indictment” of American complicity in Portuguese violence.Footnote 102 White support was necessary, and it need not conflict with the leftist anti-imperialism so central to the PALC's understanding of black internationalism.

Figure 7. The poster captured the full mobilization of society that lay at the heart of the Portuguese African liberation movements. It also paralleled the image of the revolutionary black mother popularized by Black Panther artist Emory Douglas, creating a transnational logic of Black Power in image and words. Republished with the permission of Brenda Randolph (Michigan State University Libraries Special Collections).

While the PALC sought to cross the racial divide in these ways, it never abandoned the belief that the Gulf Boycott had to be a “Black community thrust.”Footnote 103 It continued to bar white membership, lest whites dilute the pan-African leadership of the group, its critique of the unjust American system, or its ability to appeal to often wary black communities.Footnote 104 Robinson concluded that African Americans needed to maintain direct control of the movement's core in order to keep it focused on the specific needs and desires of African-descended peoples, even if they also needed some white cooperation to achieve their goals. It was this model of organizing—centered on a radical pan-Africanism but dedicated to assembling a spectrum of allies by appealing to an inclusive anti-imperialism—that became Robinson's guiding political strategy, both as head of the PALC and in his later work against apartheid. In this way, the PALC paralleled the evolution of other Black Power organizations committed to anti-imperial Third World Leftism, notably the Black Panthers, whose National Committee to Combat Fascism sought to preserve its black identity while building multiracial alliances to contest elections.Footnote 105 Robinson had struck upon a less centralized and therefore more flexible model that that had no ambitions of forming a political party or aligning itself directly with one, but which was still able to challenge policy and influence politicians. A black core could guide a grassroots movement, mobilizing wider constituencies in support of African and African American self-determination by utilizing the time-tested tactics of economic protest and public demonstration.

The ALSC moved toward a similar model of organizing, though not without disagreement. Unlike the PALC, whose pan-Africanism had always incorporated an anti-imperial economic logic, the ALSC's fragile coalition had depended on an unlikely unity between exclusionary black nationalists and leftist pan-Africanists. As the leftist ideology became more popular, a schism in the movement developed. This culminated in a victory by leftists for control of the ALSC, enshrining in 1973 an anti-imperialism that aligned with the less racialized systemic critique championed by African nationalist movements and Black Power advocates like the PALC.Footnote 106 In response, the black nationalists split from the ALSC. African Liberation Day continued in competing formats, with the ALSC remaining the more influential of the factions as it kept ties to prominent black leaders including Baraka, Angela Davis, and the elected officials of the CBC.

This ideological tension helped scuttle prospects for a black electoral political movement and undermined the broader agenda approved at the Gary conference, but solidarity with African revolutions transcended this political divide. By the time the ALSC split in 1974, the PALC and its affiliates had established the Gulf boycott and its critique of American business as a national movement. Gulf remained in Angola, but it worried about the impact of the protests on its image. In addition to pledges affirming a greater emphasis on job equality in future projects, it launched a public relations campaign aimed at softening the blow of demonstrations. The company took out full-page advertisements in popular black publications highlighting Gulf's positive impact on local communities. It also increased investments in minority training programs. A $50,000 gift to the SCLC aimed to co-opt major black leaders, but instead it revealed the pressure placed on political elites: Most media coverage downplayed the gift in favor of emphasizing boycott supporters’ angry attacks on Ralph Abernathy for accepting tainted money.Footnote 107

A movement had taken shape, linking support for African liberation with opposition to Gulf. The PALC and its allies had yet to isolate Portugal, but their actions put companies like Gulf under increased scrutiny for their complicity in southern Africa. They popularized interest in the liberation movements, which spurred increased attention to socialist African parties and their representatives, and in turn to questions of local self-determination more broadly.

Conclusion and Coda

The PALC and the Gulf boycott helped many African Americans forge a sustainable sense of solidarity with struggles in southern Africa, and it established a model for future organizing. In April 1974, as the anti-Gulf movement continued to expand, the weight of the colonial wars finally broke the resolve of the Portuguese regime. A cadre of young army officers toppled the Lisbon dictatorship. In just over a year, Portugal granted independence to all of its colonies. Gulf's payments to operate in Angola now went to the MPLA; FRELIMO took power in Mozambique and the PAIGC in Guinea-Bissau. African American activism had not caused the collapse of the Portuguese empire or forced Gulf to withdraw from Angola, but it had fostered a meaningful international network that gave new momentum to activism on behalf of southern African issues. That the PALC's actions had not forced Gulf to retreat mattered little, since Robinson viewed the oil giant “more as a tool than a target.”Footnote 108 For SARF and the PALC, the goal had always been to educate and organize.

If the Gulf campaign defined one successful logic for mobilizing African American communities, it also demonstrated the limits of black American support for African governments after the end of white rule. Pan-African activism owed much to a sense of shared exploitation and strategies of resistance, but this solidarity broke down as political dynamics changed in the wake of decolonization. The MPLA gained the power to negotiate with Gulf, while African American communities remained economically marginalized. The decision by the socialist MPLA to work with the unrepentant corporation alienated some radical supporters and sowed confusion among those still set on opposing the multinational's operations.Footnote 109 These transnational dissonances merged with Angola's 1976 civil war between competing black nationalist parties—both of which sought aid from allies in the United States—to further complicate African American engagement with Lusophone Africa. The anti-imperialism of the Gulf campaign had offered a clear moral choice that furthered the goal of domestic unity envisioned by Black Power, but the complexities of postcolonial Angolan politics proved difficult to translate for U.S. domestic consumption and often divisive when tried. Successful organizing fared better with issues that were both literally and figuratively black and white. Robinson would find it difficult to motivate African Americans to act on such challenging issues as Angolan sovereignty and Ethiopian democracy over the next decade.

Though Gulf faded from the activist agenda, the campaign's critique of U.S. foreign relations provided an accessible framework for mobilizing African American communities against the issue of apartheid. The Gulf campaign, at least for a time, helped undermine a mindset that discouraged blacks from engaging in international action, because—as Robinson summarized—“Black people have always known … in our collectively delimiting racial subconscious, who owns the country and just how closely those owners listen to us.”Footnote 110 African nationalists like Chris Nteta and the FRELIMO leadership rejected these limitations, and encouraged individuals such as the Robinsons to affirm their ownership of U.S. foreign policy. The internationalism that these foreign actors helped to inspire was leftist, conscious of the power of mobilized black communities, and willing to challenge the economic and imperial traditions of U.S. policymaking. In important respects it revitalized African American critiques of U.S. foreign relations that had flourished in the 1940s and expanded the political impact of such anti-imperial perspectives by merging them with techniques for grassroots organizing.

During the late 1970s and 1980s, African Americans greatly expanded their influence in international affairs, most notably in the establishment of TransAfrica in 1977. Randall Robinson, as the group's first director, initially sought to change U.S. policy through traditional means by working for Diggs, cultivating State Department contacts, and testifying before Congress, but eventually he reverted to tactics that had proven so successful in the early 1970s. Highly public, disruptive actions mobilized African Americans, garnered national attention, and motivated wider protests. TransAfrica's famed 1984 occupation of South Africa's Washington embassy—which helped launch the Free South Africa Movement—closely resembled the earlier Harvard demonstration in both style and intent. It differed primarily in that it featured elected officials rather than students and took place on Massachusetts Avenue rather than in Massachusetts Hall. And like SARF and the PALC, TransAfrica remained exclusively black: “We have things to say to [our community] that don't apply to the other communities.” Still, it also worked “shoulder to shoulder” with groups such as ACOA and depended on Protestant churches for funds.Footnote 111

As TransAfrica became prominent in leading the anti-apartheid movement, it replicated key aspects of the Gulf campaign. Its radical, confrontational ideology of change drew on some of the more egalitarian and assertive elements of Black Power without alienating more cautious African Americans and white advocacy groups. It preserved a model of insurgent politics that carefully steered between the poles of militant revolt and accommodation. This approach proved pivotal in publicizing the anti-apartheid cause in the 1980s and expanding the membership of the decentralized movement that agitated for divestment locally and national sanctions against South Africa. Robinson's continued linkage of international inequality and a broad reformation of domestic economic and race relations often became lost in the growing clamor for action against apartheid, but there is little doubt the actions had important effects on the American relationship with South Africa. The passage of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 owed much to the popular momentum created by groups such as TransAfrica, ACOA, and myriad local organizations like those that became especially prominent in Boston, as well as the congressional alliances formed with politicians, particularly the members of the CBC. The passage of this law over the veto of President Ronald Reagan illustrated the power of the anti-apartheid movement. The Black Power goals of reforming American society remained elusive, but African Americans had achieved a voice within U.S. foreign relations.