Introduction

In preindustrial societies, commons were lands on which a variety of ancillary productive activities were conducted to supplement the subsistence of farming families. These include the right to collect wood, sow seeds (cultivation), take water, and even stay overnight (Bonan, Reference Bonan2015; Bulgarelli Lukacs, Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks, Alfani and Rao2011, Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks2015). Additionally, and importantly, this also included the right to graze (fida) and overall, these resources provide multilevel welfare at the environmental level. The decline of these resources is attributed to the enclosure of open fields, a phenomenon that has been studied in detail in the existing literature (Demélas & Vivier, Reference Demélas and Vivier2003; Vivier, Reference Vivier and Broad2009). However, Robert Allen (Reference Allen1982) revised this interpretation, questioning the relationship between efficiency and enclosures. Even after the advent of industrialisation, the commons continued to play a pivotal role in the self-government processes of local communities. It is crucial to examine the evolution of management practices for these properties (Ensminger, Reference Ensminger1996; De Moor & Tukker, Reference De Moor and Tukker2015) in order to assess their adaptive capacity (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2005; Folke, Reference Folke2006; De Moor, Reference De Moor2015) and their potential for preservation for future generations in the context of macroeconomic and political changes. During the long nineteenth century, it is essential to consider Hardin’s (Reference Hardin1968) argument that the decline of the commons was also due to the difficulty of implementing regulatory processes by communities because most social classes tend to maximise their interests. In response to this, Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990) and Neeson (Reference Neeson1993) offered critiques of Hardin’s (Reference Hardin1968) positions and analysed the ability of communities to initiate forms of self-regulation of the commons.

The objective of this study is to observe the responsiveness and redefinition of commons management by local institutions in Southern Italy following the national policies of privatisation and quotizzazione (the division of state property into shares among farmers) promoted by the Liberal State during the second half of the nineteenth century. It will focus on municipal regulations of commons management, an indispensable and new source for analysing management policies from a micro perspective, building on the literature, which has recently returned to this specific issue with regard to the English case (Winchester, Reference Winchester2022). This allowed us to test the adaptability of the governing principles proposed by Elinor Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990) and observe how these assets were integrated, following the literature, within the agrarian economies of different communities.

This analysis was conducted to address the following areas: 1) The study of commons management regulations allows for the identification of symptomatic elements to detect the presence of good practices of shared and inclusive organisation and collective action observed in the literature (Dietz et al., Reference Dietz, Ostrom and Stern2003; Meinzen-Dick et al., Reference Meinzen-Dick, DiGregorio and McCarthy2004; Araral, Reference Araral2009; Mosimane et al., Reference Mosimane, Breen and Nkhata2012; Winchester, Reference Winchester2022); 2) Were the commons able to overcome the pressure of exogenous post-unification shocks to privatise them, taking into account the difficulties in the relationship between different territorial stakeholders (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Brockington, Dyson and Vira2003)? It is significant to concentrate the attention on periods of shock in order to observe the responsiveness of rural communities (Soens & De Keyzer, Reference Soens and De Keyzer2022). In particular, we seek to address the question posed by Bulgarelli Lukacs (Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks2015) regarding the management capacity of southern municipalities over time, taking into account the difficulty of some institutions in responding to changes over time (Winchester, Reference Winchester2022).

This study’s time frame highlights a crucial point in the history of the commons in Italy: the Questione Demaniale which emerged during the latter half of the nineteenth century and ignited a contentious debate within the institutional realm. The fundamental problem was the absence of land reform in Southern Italy. Instead, this was intended to result from the division of state-owned latifundia (Caroppo & Mastore, Reference Caroppo and Mastore2018), which would then lead to the emergence of a class of small farmers. The underlying assumption was that southern agriculture could progress through the implementation of redistributive mechanisms of land ownership.

This attempt to reorganise collective resources, which had already begun before the unification of Italy, coincided with a period of strong exogenous solid shocks highly indicative when studying the processes of environmental resource management because the changes within agriculture – migrations and changes in cultivation – following the deflation of the 1880s. (Zamagni, Reference Zamagni1981; Pescosolido, Reference Pescosolido1998; Fenoaltea, Reference Fenoaltea2006). This transformed the production relations and distribution of crops, thereby also modifying the methods by which the commons were accessed and utilised. We can also draw on comparative studies of other places. During the same period in Scotland, for example, as a consequence of the social tensions generated by the Crofter’s War, a process of reorganisation of collective resources was initiated (Winchester, Reference Winchester2022). This shows similarities with the southern Italian case analysed in this study with regard to grazing management. This is especially relevant in light of the significance of grazing land generally, given the correlation between sheep farming practices and the existence of robust common land rights (De Keyzer & Van Onacker, Reference De Keyzer and Van Onacker2016).

In light of these substantial macroeconomic shifts, it is crucial to examine the capacity of communities to withstand external challenges (Lana Berasain, Reference Lana Berasain2008; Folke, Reference Folke2006; Wilson, Reference Wilson2012; French, Reference French2024) and the development of resilience (Folke, Reference Folke2006). This resilience, understood as a heterogeneous process (De Moura et al., Reference De Moura, Ferreira-Neto, Pérez-Fra and García-Arias2021) similar to Wilson’s (Reference Wilson2013) concept of strong sustainability, can be observed through the examination of management structures. In the context of this study, the term ‘resilience’ refers to the capacity to maintain the integrity of common land in the face of national pressures for land division, through the implementation of tailored management strategies. This research focuses on 12 municipalities in three major mountain areas (Monti Lattari, Monti Picentini, and Monti Alburni) in the province of Salerno (Campania Region), which are homogeneous in terms of social and economic structure (Figure 1). Salerno is particularly relevant because the province was one of the areas with the most significant presence of commons (19,000 hectares) in Campania (AS SA, Atti Demaniali, 979). Today, it has the highest number of management regulations still in force. In Campania, out of a total of 550 municipalities, only 58 (11%) have regulations for the management of commons; of these, 67% are in the province of Salerno (Campania Region data).

Figure 1. The sample study area.

Source: Own elaboration on geographic information system (GIS).

This case study is important because it introduces new evidence into the international debate on commons management practices (Armitage, Reference Armitage2008; De Moor et al., Reference De Moor and Laborda-Pemán2016; De Moura et al., Reference De Moura, Ferreira-Neto, Pérez-Fra and García-Arias2021). Firstly, it uses historical data to give a longitudinal dimension to research (Laborda-Penám & De Moor, Reference Laborda-Pemán and De Moor2016) that has recently received considerable attention at the European level allowing analytical explanations of the management systems of England, the Netherlands, and Spain (De Moor et al., Reference De Moor and Laborda-Pemán2016). This approach has been preferred to contemporary approaches (Poteete et al., Reference Poteete, Janssen and Ostrom2010) that have hardly allowed measurement of changes in organisational rules as pointed out by Ostrom (Reference Ostrom2014). Secondly, it focuses attention on Mediterranean Europe, a relatively neglected area with the exception of Spain (Lana Berasain, Reference Lana Berasain2008; Lana Berasain and Iriarte-Goñi, Reference Lana Berasain and Iriarte-Goñi2015; Delgado-Serrano et al., Reference Delgado-Serrano, Oteros-Rozas, Ruiz-Mallén, Calvo-Boyero, Ortiz-Guerrero, Escalante- Semerena and Corbera2018), compared to that of the Central North, where the literature has focused more attention (Neeson, Reference Neeson1993; De Moor et al., Reference De Moor, Warde and Shaw-Taylor2002; Béaur et al., Reference Béaur, Schofield, Chevet and Pérez-Picazo2013; Larsson, Reference Larsson2014) and helps to bridge the gap relative to the Italian case for the contemporary period.

For this study, archival sources were utilised, following the main trends in the international literature (Bulgarelli Lukacs, Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks2015; De Moor & Tukker, Reference De Moor and Tukker2015; De Moor et al., Reference De Moor and Laborda-Pemán2016; Vázquez, Reference Vázquez2020; Winchester, Reference Winchester2022), centred on an examination of management regulations through a comparative diachronic perspective. A multilevel methodology was adopted, as it is essential to start from the micro-scale and the archival record to reconstruct a managerial history of collective resources in Southern Italy. As Giovanni Favero (Reference Favero and Lanaro2011) has written, microhistory can help us understand, through a social science approach, the degree of creativity and heterogeneity with which different social actors try to give answers to different problems. In this regard, microhistory represents a valuable framework for examining specific historiographical interpretations. It should be noted that this approach has yielded significant insights into the agrarian field; for instance, the reinterpretation of the backwardness of sharecropping through the analysis of farm accounting (Galassi, Reference Galassi1986; Biagioli, Reference Biagioli2000; Zanibelli, Reference Zanibelli2024). The micro-historical approach has also been discussed in the context of the management history (Decker, Reference Decker, Weatherbee, McLaren and Mills2015), and is significant in the context of collective resource management.

Archival research was carried out in several institutions: the State Archives of Salerno (AS SA), the Commissariato per gli Usi Civici per la Campania e il Molise (CUCCAM), and the Central State Archives (ACS). In this way, it was possible to identify material produced before and after the unification of the State (1861), which made it possible to reconstruct the models of management of these public estates, as well as the ability of the municipalities to manage the essential resources for these mountainous areas, characterised by economic depression and a low propensity for structural changes in agriculture, particularly in the short term. The archival documentation enabled a reconstruction of the types of organisation and the actual management capacity of local institutions, taking into account that the presence of specific regulatory frameworks affected rural development (De Moura et al., Reference De Moura, Ferreira-Neto, Pérez-Fra and García-Arias2021). The sources used in this study are original and relevant, in accordance with the prevailing trends in the literature (Bulgarelli Lukacs, Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks2015) and allow us to introduce new elements in the historiographical debate on the management of commons, understanding that during the modern era, management references, when they were not present in municipal statutes, were essentially based on customary norms (Bulgarelli Lukacs, Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks, Alfani and Rao2011).

The article is structured through the following sections: an outline of the historical framework; a description of the historical-institutional evolution of commons in Southern Italy from the nineteenth to the twentieth century; the relationship between commons and agrarian economy in the province of Salerno; and analysis of new historical evidence regarding the quality of commons management by the municipalities studied during the post-unification period; discussion of the results and finally the conclusions.

Historical framework

The international historiography has attempted to respond to the concept of ‘tragedy’, which Hardin (Reference Hardin1968) theorised, by focusing on management practices. The ability of local communities to protect the commons from the macro changes that have occurred since the Industrial Revolution has often been determined by the presence of regulatory practices that have been developed over centuries and have ensured a solid organisational structure for the management of these resources. In particular, it has been demonstrated that the management policies of commons (Armitage, Reference Armitage2008; Farjam et al., Reference Farjam, De Moor, van Weeren, Forsman, Dehkordi, Ghorbani and Bravo2020; De Moura et al., Reference De Moura, Ferreira-Neto, Pérez-Fra and García-Arias2021) align with those trajectories that are conducive to achieving sustainable development (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Ferrara, Wilson, Ripullone, Nolè, Harmer and Salvati2015) and the emergence of multifunctional communities (Cheshire et al., Reference Cheshire, Esparcia and Shucksmith2015). For example, English commoners have been observed to engage in self-regulatory actions (Thompson, Reference Thompson1991; Neeson, Reference Neeson1993; Winchester, Reference Winchester, Van Bavel and Thoen2008, Reference Winchester2022), which confirms that they were not resources that experienced irreversible decline due to the agricultural revolution. Indeed, the presence of a balanced community with a wide variety of stakeholders, who influenced decisions within the village led to communal lands being well governed and remaining inclusive, as some European regional case studies demonstrate (De Keyzer, Reference De Keyzer2013).

The application model proposed by Elinor Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990) in her seminal work was designed to test individuals’ adaptability and management practice. Ostrom’s theories of commons governance are based on the following principles: having defined boundaries; congruence between appropriations and local rules; collective elections guaranteed by specific rules; oversight of management aspects; secure penalties for violations; the existence of dispute resolution mechanisms; the right of principals to set their own rules; and recognition by external local authorities. Subsequent studies have corroborated this approach by verifying its adaptability (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Arnold and Tomás2010) and augmenting it with new cases where it was observed that even in the presence of specific management rules designed to encourage controlled access, these could be disregarded by excluding the poorest citizens (Winchester & Straughton, Reference Winchester and Straughton2010) for exclusive use by elites. Ostrom’s (Reference Ostrom1990) work also highlighted the need for comprehensive, long-term studies of common management patterns that employ a historical approach. Such studies enable us to comprehend the adaptability and resilience of these properties in the context of significant macroeconomic shifts. The study of rural statutes (or regulations) is crucial because it allows us to move beyond custom by becoming an expression of current policy and measuring the forms of local politics (Raggio, Reference Raggio1995). In the English case, for example, the statutes present a fundamental set of customary rules, some of which appear to have national and international implications, while others reflect local particularities (Winchester, Reference Winchester, Van Bavel and Thoen2008).

This was the approach taken by the research team behind Common Rules. The regulation of institutions for managing commons in Europe, 1100–1800 (project name), where they used historical data to measure commons management policies in a longitudinal and comparative dimension (De Moor & Tukker, Reference De Moor and Tukker2015; De Moor et al., Reference De Moor and Laborda-Pemán2016). The team focused on three specific areas: the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Spain. They were going to observe and classify, through the creation of a database, the rules and regulations for the management of commons. Studying the evolution of management practices and institutional change (Ensminger, Reference Ensminger1996; French, Reference French2024) is essential because customs and rules played a vital role in the survival of collective goods that were the preserve of self-governing communities (Van Zanden & Prak, Reference Van Zanden and Prak2006; De Moor, Reference De Moor2008, Reference De Moor2009; Bulgarelli Lukacs, Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks, Alfani and Rao2011). This institutional structure has characterised the European case in the global landscape (Putnam, Reference Putnam1993). The work of the Common Rules group revealed the existence of significant heterogeneity in management practices. In particular, the English case demonstrated a greater propensity for implementing sanctions, with a top-down diffusion of rules through seigniorial courts. In contrast, the Dutch and Spanish experiences illustrated a bottom-up structure designed to develop management systems that fostered cooperative actions among the parties involved. The case studies revealed a tendency to identify rules that would prevent free-riding and limit resource depletion. Additionally, it became evident that the preservation of the commons occurred not so much through the presence of sanctions but instead through the introduction of new forms of management and citizen participation (Boyd et al., Reference Boyd, Richerson, Meinzen-Dick, De Moor, Jackson, Gjerde and Dye2018). Specifically, De Moor’s note; De Moor & Tukker, Reference De Moor and Tukker2015). This holds that commons can also take on the traits of intangibles, mainly focusing on the concept of institutions for collective actions (De Moor, Reference De Moor, Brousseau, Glachant and Sgard2021). As extensively explored by the research group Institutions for Collective Actions (whose principal investigator is Tine De Moor), shared actions refer to the values to be transmitted to community members for the preservation of the municipal perimeter and the dissemination of good practices of territorial governance. These ideas form the basis of community operations to foster corporate collective actions related to local legal institutions.

Considering the findings of this particular field, it is imperative to extend the scope of analysis to include other regions that have retained a substantial legacy of common resources (both qualitative and quantitative), with particular focus on the Italian Peninsula. Several studies have examined the evolution of commons in Italy, with a particular emphasis on the modern era (Corona, Reference Corona1995, Reference Corona2004, Reference Corona2013; Alfani and Rao, Reference Alfani and Rao2011; Mocarelli, Reference Mocarelli2015; Ongaro, Reference Ongaro2016; Bonan, Reference Bonan2016). However, these studies have yet to delve into the specifics of management systems. An early work that did address the management of commons was Alessandra Bulgarelli Lukacs’ (Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks2015) study of Southern Italy. This established the foundation for an analytical research of organisational practices and collective resource management. Additionally, Marco Casari (Reference Casari2007) had previously highlighted the significance of establishing rules for the efficient use of the commons. The research presented in this article is in line with the tradition of study described above. It addresses a significant gap in the literature by examining collective resource management practices in a period of strong transformation from a diachronic perspective. It places the Italian case, specifically that of the Mezzogiorno, within this specific body of literature, which has achieved significant results for other areas of Europe.

Commons in Southern Italy: institutional structure and management practices

As documented in the agrarian inquiries of liberal governments, the towns in the Mezzogiorno lacked an institutional framework (regulations) for the protection and enhancement of commons (Bordiga, Reference Bordiga1909; Corona, Reference Corona2004). According to the main interpretation, local institutions of the municipalities in the South were weak and under the control of a few large landowners, which prevented them from developing community management practices in the region comparable to those in Central Europe (De Moor, Reference De Moor2009; De Moor et al., Reference De Moor and Laborda-Pemán2016). Regarding the post-unification period to measure the real administration capacity of collective resources by municipalities, it is important to analyse new historical sources such as management regulations.

Between the 18th and 19th centuries, the legal and management structure of commons in Southern Italy differed significantly from that of other Italian areas, particularly in Northern Italy. In the latter case, the commons fell within those resources administered by groups or communities through specific ‘rules’ (Corona, Reference Corona2004). In this sense, collective properties were not merely a legal or economic instrument; they represented a distinct form of ownership that bound people together through social relationships and united the people with their surrounding landscape (Grossi, Reference Grossi and Carletti1993). They embodied a vision of development that differed from capitalist development and became the foundation upon which the village economy was based (Daly, Reference Daly1973). These assets were given different names and managed through different structures, but they were unified by a common factor: the right of access was granted through membership of small groups of people (Corona, Reference Corona2004). In the Umbro-Marchigiano Apennines, these were Comunanze, in which family heads divided the rents of collective resources and decided their management through village assemblies (Croce, Reference Croce1992). A comparable phenomenon was observed in the Società degli Originari of Lombardy and Veneto, where access to the collective resource was contingent upon family membership (Pace, Reference Pace1975). In Cadore, there were Regole, which were administered by small groups (co-heirs) representing the various families that constituted the community. Common property was not owned by citizens but by communions of families (Pace, Reference Pace1975). In the plains of Bologna, there was the Partecipazioni, which required that in order to participate, one must be a citizen and physically reside there (Arioti, Reference Arioti1992). Other forms included the Società della Malga, which allowed access to common resources to those who owned certain livestock. In addition, access to the Università Agrarie resources in Latium was contingent upon ownership of two plough oxen (Cencelli-Perti, Reference Cencelli-Perti1890); in Sardinia, there were the Ademprivi.

This form of management was strongly linked to family and micro-group structures, making it difficult to quantify the real size of these resources in hectares (Corona, Reference Corona2004). The absence of local institutions in the management processes significantly complicated a census of these properties, a first census of the commons was conducted by Istituto Nazionale di Economia Agraria (INEA), which published a series of volumes by region, including the Campania (INEA, 1947). This difficulty persists to the present day and must be extended to the entire Peninsula. Prior to unification, the Mezzogiorno (Kingdom of Naples and Kingdom of the Two Sicilies) addressed the Questione Demaniale during the French period following the annexation of the Kingdom of Naples. During this period, economic statistical studies were conducted for each province with the objective of measuring the economic capacities of the various provinces of the Kingdom of Naples (Pedìo, Reference Pedìo1964). Furthermore, it is essential to consider the impact of regulatory enhancement on the commons. The commons, a system based on the fluidity of law during the Ancien Regime, could have been undermined by such regulatory enhancement (De Moor, Reference De Moor2009). Therefore, during this period, it became crucial to measure the ability of organisations to govern collective resources.

The reorganisation of the commons was initiated by the legal abolition of feudalism (1806), which, inspired by the French Revolution, sought to rid Southern Italy of the last vestiges of feudalism. The authorities attempted to initiate a process of freeing the land from the last feudal burdens to promote the growth of agriculture through mechanisms of allotment of these properties, as elsewhere in Europe (Demélas & Vivier, Reference Demélas and Vivier2003). These operations were entrusted to allotment commissioners in 1809, who were charged with initiating a plan for settling disputes over state property, which was to be completed in 1811. However, the government authorities soon realised that the proposed measures for the division of common land could not initiate processes of agrarian growth and transformation, but would, on the contrary, affect the forestry and pastoral economy. Another problem was that most of the beneficiaries of the allotments did not have the means to maintain them and ended up putting them back on the market, thus favouring their acquisition by existing landowners, leading to further concentration of property. To attempt to resolve these critical issues, the Bourbon government entrusted the management of these practices to the Consiglio d’Intendenza (1816) and, for a short period, to the Consiglio Provinciale. In 1816, it was established that land could not be resold for ten years after it had been acquired, and if it had not been cultivated for three years, it would revert to state ownership. The main problem that plagued the Southern commons was usurpation and claims by the various territorial actors, including municipalities, ecclesiastical bodies and landowners.

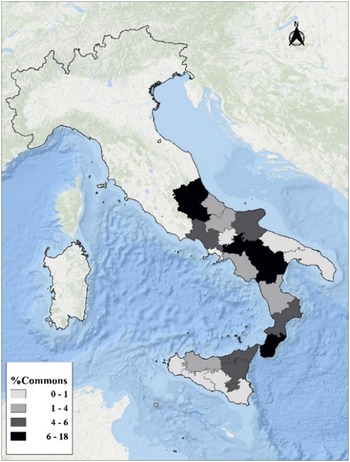

The Unification of Italy (1861) saw the establishment of a system of state powers entrusted to commissioners, assisted by special agents. In the event of conflicts, these agents assumed the role of conciliatory judges. Their initial task was to distribute lands on which there were no disputes among farmers. Concurrently, they were to manage the dissolution of ‘promiscuità’ (shared use). Intercommoning was prevalent in all these border areas and consisted of sharing land or rights of use and grazing (Bulgarelli Lukacs, Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks, Alfani and Rao2011). This situation caused uncertainty about property rights, which inevitably led to conflicts between municipalities (Cerrito, Reference Cerrito1988), as evident from the archival record (AS SA, Atti Demaniali). The presence of conflicts over the boundaries of these assets has also been noted in the Scottish case (Winchester, Reference Winchester2022). Additionally, forms of intercommoning existed in Spain and England (Shannon, Reference Shannon2012; De Moor et al., Reference De Moor and Laborda-Pemán2016). However, the latter procedure often led to the emergence of disputes between municipalities. The commissioners’ work was to be concluded by 1861, and in 1865, the prefectures assumed responsibility for matters pertaining to state property, including the resolution of disputes related to the dissolution of promiscuities. It was not until the enactment of Fascist legislation in 1927 that the state intervened on a national scale to facilitate the reorganisation of commons. The fact that these estates were under the control of territorial institutions meant that at the beginning of the twentieth century, it was possible to arrive at a dimensional estimate (MAIC, 1900, 1902) of state lands (658,000 hectares) and those subject to commons (407,000 hectares) in the Mezzogiorno (Figure 2); most of these were located in the provinces of the Southern Apennines. The availability of these data is essential in initiating comparative studies between different regions of the South.

Figure 2. Distribution of commons in Southern Italy (1900).

Source: Own elaboration on MAIC (1900, 1902); MAIC (1913). The commons indicator represents the percentage of land allocated to communal uses out of the total agricultural and forest land area in the provinces.

It is notable that regarding the management and organisation of commons in the South of Italy, there were no collective properties; however, forms of association among livestock owners were prevalent in Apulia (Marino, Reference Marino1992). There were various forms of demesne, including royal, feudal, municipal, and ecclesiastical. As Alessandra Bulgarelli Lukacs (Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks, Alfani and Rao2011) wrote, a close relationship existed between feudal tenure and demesne. In the Kingdom of Naples, the term ‘demesne’ was used to refer to land (feudal and ecclesiastic) over which rights of use were exercised by the population. Additionally, ‘demesne’ denoted the property owned by Universitas (the name of the municipality in pre-unification time). Following the conferral of legal status by the sovereign, the Universitas acquired the capacity to hold common land (Bulgarelli Lukacs, Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks2015:123). A comparable legal structure concerning usage rights was identified in the Scottish case (Winchester, Reference Winchester2022:44).

The institution of the Bagliva (an ancient local court) was also extended to these properties to such an extent that it was said that ‘ubi feoda ibi demania’, a peculiarity similar to the English case (Thompson, Reference Thompson1991; De Moor et al., Reference De Moor and Laborda-Pemán2016). The towns also administered their property, and there were forms of co-partnership between different municipalities (promiscuità). The commons management was likened to municipal property and integrated into a balance sheet, but with a vital prerogative: inalienability. The principal rights of use were as follows: a) the free exercise of rights uses (collection of dry wood, plants and mushrooms, water, and even overnight stays); b) the license for grazing livestock; c) the concession of small shares in emphyteusis through an annual rent. In the Mezzogiorno, commoners used commons in a different sense than collective ownership. The latter case presupposed the existence of solid ties between object and community in which there was no room for individualistic forms. Moreover, if, for the North, we speak of rights of use, for the South, we speak of inviolable rights owed to citizens because they were members of the community; this category also included all those who had been domiciled and had paid taxes in the municipality for a long time (Corona, Reference Corona2004).

The commons were a vital component of the Southern rural economy and were the subject of significant claims between various stakeholders, including the towns, landowners, the church, and farmers. Centuries-old conflicts arose around the boundaries and management of the commons, as evidenced by archival records (AS SA, Atti Demaniali). In this context of high litigiosity, it is also essential to study the management policies of territorial institutions and their adaptive capacity (Evans & Reid, Reference Evans and Reid2015; De Moor et al., Reference De Moor and Laborda-Pemán2016) to define the long-term role of commons in implementing effective environmental protection practices (Scott, Reference Scott2013). This analysis is essential to prevent hydrogeological disruption and facilitate resource redistribution processes in the marginal areas of the Southern Apennines.

Commons and agrarian change in Salerno after National Unification

This study allows for the study of twelve municipalities located in the different mountainous areas of the province, demonstrating the heterogeneity of the territory. These realities are closely intertwined with the mountain economic system, in which collective resources and other activities (small-scale manufacturing) serve to complement agriculture. The soil was not particularly fertile, and the majority of the land was classified as third class (according to the Murattian Cadastre). In the case of Acerno during the early nineteenth century, the agrarian economic system proved inadequate in meeting the needs of the community. This assertion was corroborated by the mayor of Acerno during a dispute with the local church (Capitolo). In his argument, he asserted that the commons were vital for the economic sustenance of the population: ‘Da Pochi anni con privata autorità il Capitolo à preteso impedirne l’esercizio, con sostenere la liberà degli enunciati fondi […] questo avrebbe creato diverse difficoltà […] ai bisogni purtroppo seri degli infelici cittadini di Acerno (For the past few years with private authority the local church has pretended to prevent its exercise, with sustaining the freedom of the stated lands […] this would create several difficulties […] to the unfortunately serious necessities of the unfortunate citizens of Acerno)’ (AS SA, Atti demaniali, 1:4). A comparable phenomenon is evidenced by the case of Castiglione del Genovesi, where an effort was made to delineate the utilisation of chestnut harvesting as a means of bolstering the town’s economic stability (AS SA, Atti demaniali, 184:14). In such an environment, characterised as early as the early nineteenth century by a deficit between grain production and consumption, it became necessary to resort to forms of commercialisation of timber and other products derived from the commons to purchase the missing foodstuffs that had to be regulated to prevent their uncontrolled use.

It is evident from a mapping of food and agricultural typicality carried out in pre-unification period (Siniscalchi, Reference Siniscalchi2019) that livestock farming constituted a significant weight in the economy of these territories. In the 1880s (MAIC, 1882), the distribution of livestock (donkeys, cattle, goats, sheep, and pigs) in the observed territory ranged between 4 and 12 heads per ten hectares of agricultural and forest area. When this figure is related to the percentage of commons (Figure 3), it becomes evident that the majority of commons had a significant number of livestock per hectare. It is notable that a considerable number of cases exhibited a relatively limited extent of common land. In the absence of regulatory frameworks, such circumstances could have led to instances of resource exploitation and encroachment, aspects that are particularly pertinent in the context of significant external shocks, such as those experienced in the 1880s, which prompted a re-evaluation of the cropping system (Fenoaltea, Reference Fenoaltea2006). The international price deflation during this period led to a shift in preference, with a greater emphasis placed on cultivating commercial products, such as wine, over cereals (Zanibelli, Reference Zanibelli2022a, Reference Zanibelli2024). This abrupt transition in the primary economic sector gave rise to an increase in conflicts over the exploitation of these resources, with occupations by the population contributing to the centuries-old border disputes between various municipalities.

Figure 3. The ratio of livestock per hectare to commons’ area.

Note: Own elaboration on: MAIC (1882); MAIC (1913) e (AS SA, Atti demaniali 871, 874, 876, 877,878, 879). The commons variable represents the percentage (in hectares) of land of this type within the total agricultural and forestry area of each municipality. The value of commons related to Ravello was constructed with what is stated in the regulation: (AS SA, Atti demaniali, 550:28).

The resilience of the commons system in Southern Italy was demonstrated after the Unification, as a consequence of state-sponsored policies of division into smaller shares, in accordance with the practices observed in other regions of Mediterranean Europe (Lana Berasain & Iriarte-Gõni, Reference Lana Berasain and Iriarte-Goñi2015).

The official statistics, conducted by the provincial authorities and presented in aggregate form by district, indicate that a considerable degree of conflict had emerged around the commons, particularly in areas experiencing elevated levels of anthropogenic pressure and high livestock populations (Table 1). The sharecropping indicator figure is significant: it can be attributed to the fact that sharecropping, which has historically been associated with land inequality (Zanibelli, Reference Zanibelli2022b), is a variable that was strongly linked to the presence of commons in the South, which would have facilitated the development of effective collective resource management practices. The two variables would have played a role in protecting the land in those areas characterised by the high presence of micro-properties (in economic conditions bordering on subsistence). By its very nature, co-participation in production is based on an agreement between the landowner and the farmer. It would have facilitated mechanisms of organised land exploitation, which would have also protected the environmental heritage. Additionally, the positive role of sharecropping should be considered, as it would have facilitated enhanced environmental compatibility and human capital formation (Biagioli, Reference Biagioli2000; Felice, Reference Felice2007; Zanibelli, Reference Zanibelli2022b). Further confirmation of this relationship can be observed when examining the continental regions of Southern Italy. A statistically significant correlation (0.53 - significance p-value <0.01) between the presence of commons (percentage of hectares in the forest and agrarian area) and forms of sharecropping (share of sharecroppers in the total agrarian population) can be observed (Figure 4). In the Mezzogiorno, this contract differed from the traditional Tuscan contract (Biagioli, Reference Biagioli2000; Zanibelli, Reference Zanibelli2024). Instead, it represented a form of product sharing (MAIC, 1891; Russo, Reference Russo, Biagioli and Pazzagli2013).

Table 1. Commons claims and risk factors province of Salerno

Note: Own elaboration. The second column is the percentage of municipalities in the initial sample with conflicts, the term refers to all disputes between municipalities and territorial stakeholders (AS SA, Atti Demaniali , 871, 874, 876, 877, 878, 879); the third is the percentage of municipalities that were able to resolve conflicts (land occupation and boundary disputes) over commons during the period under consideration (AS SA, Atti Demaniali , 871, 874, 876, 877, 878, 879); the fourth is the value per hectare of wooded area (current liras); the fifth is the share of sharecroppers in the total agricultural population according to the 1881 census (MAIC, 1882); the sixth and seventh are the reconstructions of the value per hectare (current liras) of cattle forests through data from the Agrarian Inquiry (INAG, 1882) and the cattle census of 1881 (MAIC, 1882); the eighth indicates the value of wool in thousands of current liras (INAG, 1882); the ninth and tenth report the number of livestock units and people per hectare of land allocated to commons (AS SA, Atti Demaniali, 878).

Figure 4. Sharecropping concentration in Southern Italy (1881).

Note: Own elaboration on MAIC (1900, 1902). The sharecropping indicator is the percentage of sharecroppers in the total number of agricultural workers.

New evidence on commons management practices

This analysis of the province’s agrarian economy revealed the necessity of regulating the methods by which commons were accessed and exploited to prevent a depletion of resources (Hardin, Reference Hardin1968), which would ultimately result in a crisis for the mountain’s economic system. Furthermore, in order to respond to any exogenous shocks, it was essential to promote harmonious management models between innovation (industrialisation) and the conservation of the common land. The process of reorganisation of the management system was initiated at the urging of the central authorities, through a pyramidal pattern: firstly, an initiative by the State to order and regulate the exploitation of commons (MAIC, 1900, 1902); secondly, coordination of forms of organisation by local institutions; and lastly, implementation of appropriate management regulations by municipalities. A first attempt at a homogeneous organisation of commons had already been made during the restoration, with the promulgation of urban and rural police regulations (AS SA, Intendenza di Principato Citeriore. 57, Regolamenti di Polizia e Annona: 621-627). The regulations retained for the sample of municipalities under this study are Castiglione del Genovesi, Controne, Giffoni Valle Piana, Ottati, Petina, and Roscigno. This source is worth analysing because, due to the Law of May 22, 1808, the commons’ supervision functions, proper to the ancient institution of the Bagliva, were included among the police functions of the municipalities. The regulations (Figure 5) addressed certain typicalities related to grazing and other aspects of livestock management: ‘[…] è vietato tenere più di dieci pecore. Chi vorrà […] dovrà farle pascolare nelle contrade dette Marecina e Bacito in tempo d’inverno e nella montagna in tempo d’estate (It is prohibited to possess more than ten sheep. Those who wish to do so must graze them in the Marecina and Bacito territories during the winter and in the mountains during the summer)’ (AS SA, Intendenza di Principato Citeriore. 57, Regolamenti di Polizia e Annona: 624:2). It is notable that the regulations placed particular emphasis on the importance of sanitary protection. In response to the arrival of contagious diseases, infected livestock were isolated in designated areas to prevent the further spread of the contagion (AS SA, Intendenza di Principato Citeriore. 57, Regolamenti di Polizia e Annona: 624:9). This distinctive feature demonstrates a resemblance to the English rules that also introduced specific guidelines to prevent the introduction of infected livestock into common lands (Winchester, Reference Winchester2022).

Figure 5. Bourbon regulations of urban and rural police.

Note: AS SA, Intendenza di Principato Citeriore. 57, Regolamenti di Polizia e Annona: 624.

This documentation is essential for comparative and diachronic analyses of the regulations that are the subject of this study. A robust interaction between municipalities and higher institutions (Intendenza) emerged from the study of these documents. For each municipality, life in the town centre, annona, and rural areas (including water resources) was regulated, particularly demesne, as evidenced by the regulation of Corleto Monforte: ‘Art. 4. Questo comune abbonda di demani ove i cittadini sogliano seminare. Per evitare che discordie, contese e litigi tra i medesimi per l’occupazione di terreni è espediente adoperare le seguenti regole (This municipality abounds in demesnes where citizens used to sow seeds. To prevent discord, litigation and disputes among them over the occupation of land, the following rules are adopted)’ (AS SA, Intendenza di Principato Citeriore. 57, Regolamenti di Polizia e Annona, 622:29). Commons areas were also defined (by toponym), and in particular, the documents give relevance to the rules for the introduction of livestock into common land (AS SA, Intendenza di Principato Citeriore. 57, Regolamenti di Polizia e Annona, 624:9. Art 39 Regulations of the Municipality of Petina).

The prefecture of Salerno opted for a predetermined model structure to be adopted by the various municipalities in the territory according to national regulations (AS SA, Atti Demaniali, 879:92). The selected model was devised by Luigi Marcialis (prefect of Chieti from 1907 to 1914) and published in Rome in 1909. The document comprised 58 articles, aimed to regulate the principal rights of use observed in the common land of Southern Italy: wood gathering, grazing, and sowing (cultivation). The idea of municipalities adopting specific regulations brings to the fore an important aspect in the history of commons in Italy that needs to be explored in greater depth. Prior to this, regulations regarding commons were included within the ancient municipal statutes or entrusted to customary norms (Bulgarelli Lukacs, Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks, Alfani and Rao2011). This intervention strengthened the system of government with special management regulations (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990), which were the result of collective action by the different communities as has already been established in the existing literature (De Moor, Reference De Moor2008; Mosimane et al., Reference Mosimane, Breen and Nkhata2012) and managed by town councils (which had replaced village councils). Furthermore, the intervention sought to provide uniformity in the management of rights and customs, which were previously characterised by a high degree of heterogeneity even among neighbouring areas. This was a relevant aspect aimed at correcting any institutional and management asymmetries at a time in history when the literature indicated a decline in collective resources.

The documents analysed in this study span a range of 10–55 articles, with an average of 25 articles per community. This variation from the general pattern demonstrates the model’s adaptability to the unique needs of each community. The regulations under consideration (Figure 6) cover a period from the 1880s to the 1920s; for the municipality of Giffoni Valle Piana, we do not have the regulations but instead have resolutions of the city council regarding changes to be made to the document in agreement with higher institutions. This periodisation allows for the identification of the primary alterations to the commons during this era, which Arno Mayer (Reference Mayer1981) has defined as the conclusion of the Ancien Regime. It is important to note that different versions of the regulations were created in response to observations made by higher institutions, such as the Forest Inspectorate and Ministry, with the aim of adapting local customs to national regulations. This demonstrates that the introduction of these instruments was not merely accepted passively by municipalities; instead, it was viewed as an opportunity to protect their commons, which were essential for their budgets (AS SA, Atti Demaniali, 493:58). Furthermore, it was seen as an opportunity to initiate a dialogue with higher institutions, according to institutionalist theory (North, Reference North1990; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990; Robinson & Acemoglu, Reference Robinson and Acemoglu2012) to also study power relations for access to the commons (De Keyzer, Reference De Keyzer2013), in order to preserve these resources from external pressures.

Figure 6. Examples of commons management rules.

Note: AS SA, Atti Demaniali; 6:66; 550:27–28; ACS, Usi Civici, Sicignano degli Alburni.

The regulations were drafted in manuscript form and divided into four specific macro-sections based on the general outline (Table 2). Two of these sections pertain to regulatory matters, while the other two address purely managerial issues. These latter sections were further divided into two subsections: Firstly, the presentation and description of state property. At the same time, the second outlines the various rights of use and the size of the demesne in hectares. This aspect is particularly relevant because the municipal authorities clearly delineated the boundaries of action for the various types of rights of use on the commons. This is exemplified by the case of Acerno, where since 1801, the last feudal lord (Girolano Mascaro) had a map (preserved at the State Archives of Avellino) drawn up by the renowned architect Carlo Vanvitelli to address border disputes with neighbouring municipalities. The existence of ambiguous limits could give rise to disputes between higher-level authorities and municipalities, particularly those that had long been subjected to considerable pressure on their lands from other municipalities, landowners, and religious institutions. In the absence of a geometric cadastre, limits were based on toponyms that could be dissimilar from town to town, which made it particularly challenging to implement boundary practices; the discussion of the rules for the use of the municipality’s various uses (grazing, sowing, harvesting of timber and undergrowth products, and stone gathering).

Table 2. Structure commons management rules

Note: AS SA, Atti Demaniali , folders of the municipalities studied.

The regulations are explicit in stating that the right to utilise the commons was intended exclusively for citizens and those who had resided in the municipality for an extended period, which aligns with findings reported elsewhere (Corona, Reference Corona2004; Bulgarelli Lukacs, Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks, Alfani and Rao2011, Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks2015; De Moor et al., Reference De Moor and Laborda-Pemán2016).

The documentation revealed a significant aspect: the possibility of selling the fruits from collective resources outside the commons, confirming the essential role of the commons within the so-called village economy. The legislation is in line with what was already expressed in the Bourbon regulations, confirmed by some claims between neighbouring commons, which indicate that access to water sources was a cause of conflict between different municipalities (AS SA, Atti demaniali , in particular, the folders related to the municipality of Acerno) being in many cases located in those so-called ‘promisque’ areas that with the process of dissolution of feudalism began to be eliminated also changing the very perception of property rights. The regulations also allowed for establishing associations or companies to manage all or part of the municipal demesne, subject to the authorisation of the municipality and State authorities. The upper institutions played the role of guarantor to ensure fair consideration for the municipalities, the relevant aspect being that the municipality was also allowed a minimum of leeway in this procedure (ASC, Usi Civici, Sicignano degli Alburni. Art. 5; AS SA, Atti Demaniali, 550:27–28).

The analysis of rules allows for the measurement of the collective actions of municipalities (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2005; Folke, Reference Folke2006; Mosimane et al., Reference Mosimane, Breen and Nkhata2012; De Moor, Reference De Moor2015). A 1913 document of the municipality of Acerno, approved by a unanimous vote of the city council, revealed the presence of a dialogue between municipalities and institutions. The authorities of Acerno, citing the necessity of adapting regulatory models to the specific needs of communities, proposed a framework that would ensure the maintenance of social stability and the preservation of long-standing traditions and customs. In areas experiencing economic distress, they advocated for the community’s continued stewardship of collective resources, emphasising that this responsibility could not be transferred to external entities (AS SA, Atti Demaniali, 6:66). Further evidence of this institutional synergy can be found in a letter from the municipality of Ravello, in which it was stated to the prefecture that the problem of occupations needed to be resolved to proceed with the management of the common land, in response to a request from the prefecture to make changes to the regulations. Furthermore, a request was made to the prefecture to be able to deliberate a specific use for individual state property bodies so that the municipality’s budget could be supplemented (AS SA, Atti Demaniali, 550:27-28). In a letter in 1912, the Ministry granted the municipality’s requests and mandated that a demesne agent be appointed to solve the usurpation problem.

There were challenges, however, the municipality of Aquara had produced a regulation that needed an accurate form of organisation for a vital use such as grazing, as noted in a letter (1912) from the Forestry Inspectorate to the Ministry. Consequently, the Ministry (1915) resolved to supersede the role of the municipality by directing the Forestry Inspectorate to produce a document in accordance with higher directives, as the municipality was unwilling to modify it, as evidenced by a resolution of the town council in 1911 (AS SA, Atti Demaniali, 36:41). This was significant, and it allows us to measure the diachronic variation in the relations between institutions. During the Bourbon era, Aquara had adopted urban and rural police regulations, which the Intendenza of Principato Citeriore had approved. These regulations contained explicit references to grazing and had not been subject to modification (AS SA, Intendenza di Principato Citeriore. 57, Regolamenti di Polizia e Annona, 621:7). These are very important examples that allow us to reread the ability to manage collective resources in the Campanian Apennines by showing, on the one hand, a significant management capacity on the part of some communities (De Moor, Reference De Moor2008; Mosimane, et al., Reference Mosimane, Breen and Nkhata2012; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Ferrara, Wilson, Ripullone, Nolè, Harmer and Salvati2015; Cheshire et al., Reference Cheshire, Esparcia and Shucksmith2015; De Moor et al., Reference De Moor and Laborda-Pemán2016) and, on the other hand, the difficulty of dialogue with higher institutions on the part of others.

Section II presents an analysis of the management structures associated with the primary rights use dispersed throughout the territory, as illustrated in Table 2. All regulations clearly define equitable policies of dry wood distribution that provide priority access to the raw material by the poorest citizens in the event of scarcity, essential for the mountain economy. Regarding this particular usage, Acerno demonstrated remarkable resilience by initiating negotiations with the Forestry Inspectorate of Salerno in 1914. These negotiations sought to include two new areas, Fragato and Occhio Caldo, close to the built-up area, within the established wood-cutting and grazing regulations. It was done with the aim of ensuring the minimum conditions for survival during the winter months. It should be noted that, as the municipality’s administrators observed, citizens had been exercising rights of use over these areas for centuries (AS SA, Atti Demaniali , 6:66). Acerno’s claim was favourably evaluated by the Inspectorate, which gave a favourable opinion to the prefecture to execute the procedure. The regulations demonstrate a clear intention on the part of the State to foster the growth of an industry related to commons, in this case, related to timber, to stimulate the economic development of these areas. Not all localities were receptive to this opportunity, however. The municipality of Petina, for instance, was not inclined to favour this practice and attempted to exclude this specific rule by colliding with the ministry. Nevertheless, the ministry intervened decisively (1909) to have it included: ‘Poiché i beni demaniali devono servire al più largo esercizio degli usi civici di cui siano suscettibili, e quindi non soltanto di quelli essenziali ed utili, ma ben anche degli usi industriali, ed è nel pubblico interesse. Di promuovere il sorgere di nuove industrie, anziché ostacolarle (Since demesne must serve the widest exercise of the rights of use to which it may be assigned, and thus not only essential and useful uses, but well as industrial uses, this is in the public interest. Promoting the emergence of new industries and not impeding it)’ (AS SA, Atti demaniali , 493:58).

The relationship between commons and the charcoal industry (again, essential for the mountain economy) was also significant. The regulations stipulated that until these cooperatives were established, the production of charcoal could be entrusted to charcoal burners in the municipality (who had to be residents), and only if these workers were absent could this specific industry be delegated to charcoal burners from other municipalities (ACS, Usi Civici, Sicignano degli Alburni). There was provision for the establishment of cooperative societies among coal workers in order to cut production costs and thus sell coal at reduced prices. The price was set lower than the market price and the price charged in neighbouring municipalities.

The most relevant and at the same time problematic aspect of commons management was grazing, which had already been addressed by Bourbon regulations where precise locations (Giffoni Valle Piana) were established for the grazing of specific animal types, such as goats (AS SA, Intendenza di Principato Citeriore. 57, Regolamenti di Polizia e Annona, 623:8). It was important because grazing fees (fida) were significant to municipalities’ finances. Furthermore, the regulation of this particular right of use showed similarities with other European realities (Table 2), particularly with regard to the forms of adoption of rules at the local scale (Winchester, Reference Winchester2022:210). This is significant for international comparisons. The different fida fees set by the municipalities allow us to identify key aspects of collective resource management. Reductions of half of the fida fee were provided for those who owned no more than ten animals; in the municipality of Acerno, the total number of animals to benefit from the reduction was reduced by half (AS SA, Atti Demaniali, 6:66).

The case of Corleto Monforte (1919) demonstrates the difficulties associated with grazing management. Some landowners attempted to protest the reduction of fida rights by organising a petition, which was signed by 134 people, or approximately 10 per cent of the population. A review of the correspondence between the municipality, prefecture, and carabinieri (police) revealed that the actions taken by the municipal administration were not extractive, but rather were necessary to implement improvements in the designated grazing areas. Archival documents demonstrated that the landowners had attempted to influence the decisions of the central authorities by including the signatures of individuals who were unable to read or write, as well as minors.

The regulations concluded with references to existing laws for penalties for violations. These were more detailed from the first decade of the twentieth century onward and revealed that there was a subsidiarity to punish any violations of the three primary rights of use. A substantial integration between national and local regulations emerged, bringing to light forms of institutional symmetry in line with what had already been achieved during the Bourbon period. The presence of precise references to the penalty system renders the rules for the management of commons complete.

Analysis of the results

This study has uncovered the existence of communal policies whose objective is to define their own rules of governance. These policies diverged from pre-established models intended to develop effective management practices, thereby promoting forms of territorial welfare. A comparable tendency, albeit in its initial stages of development, was also identified in the Bourbon regulations that constituted the foundation for the implementation of commons management practices in the southern Apennines. The sample studied demonstrated how municipalities knew how to implement forms of commons administration that did not create conflict between the different territorial stakeholders as evidenced by the literature (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Brockington, Dyson and Vira2003). It confirmed how collective actions had played an essential role in ensuring the proper use of common resources; all while seeking forms of agreement with higher-level authorities in most cases.

This is especially relevant, taking into account that this reorganisation process took place within an acrimonious climate of conflict between different actors in the area. The transition from written regulations to practical implementation for the regulation of economic activities by institutions has also been explored, particularly for those activities that had a significant impact on the local economy.

The case of Acerno is of particular significance as the archival record enables an assessment of the actual capacity of municipal authorities to manage commons. However, with the exception of the case of Aquara, the municipalities studied here demonstrate a notable capacity for relational governance and a willingness to engage in dialogue with higher institutions. The deliberations of the municipal councils, spanning several years, confirm the communities’ commitment to safeguarding commons. In addition, it was noted that the State was intent on developing good management practices to encourage the introduction of primary sector industries related to the commons, a trend already found in urban police regulations promulgated prior to National Unification. It is relevant that only the municipality of Petina needed to grasp the importance of this opportunity for the mountain economy. The structure and precision of regulations for the establishment of collective resource management societies demonstrate a predisposition to promote a key element of the literature: the emergence of multifunctional communities (Cheshire et al., Reference Cheshire, Esparcia and Shucksmith2015) that can facilitate sustainable development processes (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Ferrara, Wilson, Ripullone, Nolè, Harmer and Salvati2015). From the description of the different rights of use, the attention of the common dimension to the poorest citizens emerges with the introduction of the management rules of unique articles to facilitate their access to resources (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990). For example, timber management regulations were introduced to calm the risk of uncontrolled logging and hydrogeological disruption phenomena due to the depletion of collective resources (Hardin, Reference Hardin1968). What emerged from the regulation of planting rights is also significant. Failure to pay the due tax would have favoured the individual, in conflict with the preservation policies of village economies that were based on the principle of equity and sharing of common values, including intangible ones, which firmly bound heterogeneous groups of citizens.

The archival documentation showed that the main obstacle to the regulations’ final approval concerned pasture fees, a fact confirmed by the attention already paid to them in the Bourbon regulations, because grazing fees were part of the relationship between the community and the landowners, the latter in many cases also having governmental functions within the municipal administrations. Power groups could thus have asymmetrically directed the management of the resource. However, the study shows that the communities (Corleto Monforte) did not passively submit to pressure from the landowners. Correspondence with higher authorities, however, shows a capacity to adapt to the findings and a willingness to correct critical points, confirming an excellent adaptation to Ostrom’s principles (Reference Ostrom1990). The fact that each landowner was equipped with specific documentation to control the number of grazing livestock also suggests the presence of supervisory personnel (field guards) to control the proper use of resources. This norm demonstrates that the case of Southern Italy is analogous to other experiences in Northern Europe, where similar forms of regulation have been identified (Winchester, Reference Winchester2022).

The analysis of organisational grazing practices reveals a similarity with those in Scotland (Winchester, Reference Winchester2022) with respect to the focus on regulating grazing access rules to ensure their preservation (access fees, rational use, and periods of use). It is notable that these enhancements transpired during a period marked by exogenous shocks, demonstrating a capacity for responsiveness and adaptation among local communities. This trend has already emerged from the examination of other European contexts (Soens & De Keyzer, Reference Soens and De Keyzer2022).

Of course, regulations, by their very nature, set rules that are not necessarily then observed by communities, particularly when two essential controls are absent: firstly, strong institutions capable of enforcing the rules through the certainty of penalties; and secondly, acceptance by the community that decides not to implement the discount but the investment for future generations. Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale (ISPRA) data on ecological value were analysed to verify whether the rules contained in post-unification regulations have really protected the forest heritage. The areas studied are among those with the highest levels of this specific indicator: by ecological value, ISPRA means an indicator consisting of several variables that take into account institutional, biodiversity, and landscape aspects. Further confirmation comes from CUCCAM data showing substantial conservation of collective resources to date. Therefore, management practices would have influenced the maintenance of the state-owned heritage in the three municipalities studied.

The results that emerged from this study clearly show: firstly, a multilevel institutional synergy that helped to protect the commons and to promote economic growth actions through rational exploitation of these resources; secondly, in the Southern Apennines, the management of commons was maintained and that therefore the generalised idea of extractive institutions does not apply to these communities; thirdly, embryonic forms of homogeneous regulation of use rights had already been experimented in the pre-unification era; fourthly, the reorganisation process succeeded in materialising even in the presence of numerous territorial conflicts that could have undermined the survival of communal property; fifthly, there are elements to define the goodness of adaptation to the management model proposed by Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990) as early as the Bourbon regulations that set the importance of organising state property through specific regulations (AS SA, Intendenza di Principato Citeriore. 57, Regolamenti di Polizia e Annona, 622:29); and lastly, a greater emphasis on organisational norms than on sanctions would have been more conducive to the preservation of the commons, as evidenced by the findings in the Dutch case. (De Moor & Tukker, Reference De Moor and Tukker2015).

Conclusions

This study of management regulations has facilitated the acquisition of new and significant information pertaining to the management of commons in Southern Italy during the post-unification period, which can be applied comparatively to other parts of Europe (Laborda-Penám & De Moor, Reference Laborda-Pemán and De Moor2016; De Moor et al., Reference De Moor and Laborda-Pemán2016). The responsiveness to exogenous shocks that altered the structure of these assets has been defined as well as the resulting structural changes imposed by higher authorities. The analysis of regulations enabled the investigation of the management capacity of commons by municipalities (Bulgarelli Lukacs, Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks2015) in a temporal dimension. Moreover, the management models of southern commons were found to be broadly consistent with the model proposed by Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990). The results showed how a gradual process of defining the management of commons occurred in Southern Italy. The Bourbon rural police regulations present a clear and precise structure that makes it possible to detect a precise organisational will on the part of the institutions. Post-unitary regulations must be understood as the next step in this process; this is confirmed by the separation of the subject of commons from other topics (town and annona) and by greater accuracy regarding management. The presence of local institutions able to develop efficient forms of collective resource management by fostering forms of subsidiarity of land governance with state and provincial authorities while bringing to light the absence of risks of ‘tragedy’ (Hardin, Reference Hardin1968) is clear. This study demonstrates the attempt by institutions to develop forms of multilevel protection of the commons, through regulatory projects aimed at a constructive dialogue between the centre and the periphery, at a time of allotment of land and intense debate about the role of state property. This research also revealed an intriguing aspect that merits further investigation in the future: the presence of analogous supranational ideas for resource regulation (Winchester, Reference Winchester, Van Bavel and Thoen2008). This was evidenced by a comparative analysis of the Salerno and Scottish cases studied by Winchester (Reference Winchester2022), which revealed a common responsiveness of rural communities to defining rules for efficient resource management.

Analysis showed that the relations between different levels of territorial power were not asymmetrical but rather that small communities managed to be, at least in part, defenders of their interests by showing forms of institutional efficiency, according to institutionalist principles (North, Reference North1990; Robinson & Acemoglu, Reference Robinson and Acemoglu2012). Even if the case of Acerno was the one with greater resilience on the part of the community to make it of great interest, it would not be correct, however, to speak of a unicum because the other two municipalities also show good levels of functioning of the management system, which made it possible to detect that there were elements of widespread institutional efficiency in the Apennines during the post-unification period. The rediscovery of archival records for the analysis of commons (Bulgarelli Lukacs, Reference Bulgarelli Lucacks2015; De Moor et al., Reference De Moor and Laborda-Pemán2016; Vázquez, Reference Vázquez2020) proved particularly relevant and allowed the identification of new elements that helped to define an analytical picture of the commons management system in the sample of municipalities in the province of Salerno. In conclusion, southern municipalities’ ability to successfully organise commons with management practices characterised by the rational use of resources emerged in a climate of pressure to divide state property and in the presence of solid territorial conflicts. Such a stressful situation did not lead to the decline of the commons but to the development of good practices for protecting resources essential for the mountain economy.