Yet one race of human beings remain to be spoken of; but the individuals who compose it are not sufficiently numerous to permit them to take their place among the several great divisions of the human family which form the population of Brazil, and therefore I did not rank this among the others which are of more importance. Still the ciganos, for thus they are called, must not be forgotten.

Henry Koster, Travels in Brazil (1896), p. 399In his memoir, Filippe Patroni, one of the early leaders of the Brazilian independence movement in the province of Grão-Pará, recounts how, on one evening in 1829, while travelling with his wife through the Brazilian north-east, his camp was visited by Gypsies (Ciganos): “and there I see a band of people, men and women, some on foot, some on horseback, and one horse was carrying three, and they were all armed. Oh! I am doomed! (I told myself). They are the Gypsies. And indeed they were”.Footnote 1

After describing what turned out to be a peaceful encounter, but during which Patroni, in his words, remained “very terrified”, he manages his readers’ expectations: “But I am content to confess that I have encountered many hordes of Gypsies in all the provinces I visited; and I did not hear anybody complain about them. Quite on the contrary, I observed that they entered all kinds of farms and settlements and maintained commercial relations with all castes of people rural and urban, poor and rich.”Footnote 2

Nevertheless, he goes on to accuse Gypsies of socially harmful conduct and blames the government for a lack of effort to settle them and turn them into useful members of society:

It is regrettable that the government hasn't yet colonized those numerous groups that live wandering the roads, forcing them to establish a fixed residence somewhere and devote themselves to cultivating the land. What benefit do they bring to the State now? None. They wander around in extreme poverty, kill horses prematurely, and terrify peasants constantly, who, noticing in their area a group of armed strangers, can't ever sleep in peace. If the government settled them down, the State would garner in them laborious and useful citizens, keen for facing the task of clearing lands, able to withstand all sort of hardships, diligent in devoting themselves to all sort of arts and sciences. The century has softened their habits, and if the government were to benefit from the vivacity they have for everything, even the necromancy of fortune telling could be turned into the benefit of the Brazilian Nation.Footnote 3

Addressing a broader, cultured public, Patroni calls for the settlement of Gypsies and his arguments reflect stereotypes Brazilian elites held about them. He is particularly irritated by what he sees as Gypsies’ economic uselessness, their attitudes to long-term productive labour, and their mobility. This, as this article documents, resonates with the attitudes of Brazilian authorities, who would sporadically turn their attention to Gypsies. While Gypsies constituted only a tiny fraction of the total population, my argument is that they became visible to the authorities at times when the elites had qualms about the perceived qualities of the masses, o povo, more generally.

Over the centuries, Brazilian elites utilized all sorts of categories and stereotypes when establishing Gypsy difference and distance. Patroni's comments in relation to his vision of the modern state contrast with his personal experiences and, strictly speaking, are not of the same order as those he presents when appealing to his readers’ sense of dread and when manipulating their prejudices about Gypsies as anti-social and criminal. If one relied only on official declarations, policies, and policy recommendations, and ignored the evidence of the quotidian insertion of Gypsies into local society, one would be forced to conclude that, in Brazil, Gypsies were in a state of conflict with the authorities. This illustrates a broader point made by Leo Lucassen in this journal, namely, that in such a case, a one-sided picture of Gypsies as universally criminalized or marginal would emerge.Footnote 4

Patroni's overall message about Gypsies’ alleged social uselessness and wandering habits would surely be recognizable to his European contemporaries (although they may not have considered Gypsies physically threatening). It goes beyond this article to trace how popular and literary tropes about Gypsies circulated throughout the South Atlantic space that first emerged as a result of Portuguese maritime expansion; Patroni's book, from which the episode is taken, was published in Lisbon. What interests me in this article is how the history of policing, disciplining, and racializing Gypsies, which intimately connects the two sides of the Atlantic, goes some way to explaining such similarities. The case of Brazilian Gypsies foregrounds connected developments within locales enmeshed in a metropole–periphery relationship. I will show, for instance, that Gypsy expulsions from Portugal to Brazil, Angola, São Tomé, or Cape Verde were frequently accompanied by instructions to colonial authorities on how to treat them. If nation- and state-building efforts can be seen as having led to Gypsy stigmatization and disciplining in Portugal, in a manner similar to other European countries of the period, the determination of galleys or specific overseas holdings as a place of exile reflected the interests of specific colonies and the ways different locales interrelated within this transatlantic realm. Modern Romani identity has to be seen, at least to some extent, as a co-product of colonialism and not only of the consolidation of the European territorial nation state.

The colonial and post-colonial context underlies similarities and differences in treatment and is central to understanding the position of Gypsies in Brazil. After all, Patroni, a liberal, republican owner of enslaved people, travelled for three years after the formal recognition of Brazil's independence in 1825 but published his memoirs twenty years later – a year after Brazil outlawed the African slave trade – while living in Portugal, where he had moved after failing to be re-elected to Brazilian legislative assembly. The end of Brazil's colonial status did not mean the end of colonial relations. Patroni's call for “colonizing” the Gypsies, who “live wandering the roads”, “forcing them to fix residence somewhere and devote themselves to cultivating the land” and turning them into “laborious and useful citizens, brave for facing the task of clearing lands” are clear expressions of this, although, this time, domestic colonization is justified as nation-building. This project would, in the second half of the nineteenth century, be buttressed by new forms of racial science, which again redefined the place of Gypsies. The Brazilian case is therefore helpful in revealing that the view of Gypsies depended on the character of a specific racial regime and that their racialization must be understood in relation to the racialization of other communities.

In order to substantiate these claims – of interconnected developments within locales enmeshed in a metropole–periphery relationship; of continuities between imperial and nation-building projects; and of the centrality of race – this article focuses on the north-eastern region of Brazil, which Patroni describes in his memoirs, and in particular on Bahia – a captaincy until 1821, a province until 1891, and today a state within the Federative Republic of Brazil. It explores the complexity of interaction between Gypsies and non-Gypsies over the centuries with special attention paid to the official perspective, tracing the varied, changing, and sometimes contradictory ways in which Gypsies in Brazil were seen and treated by authorities and elites. It documents that the continued distinctiveness of Gypsies and their independent way of making a living, especially as itinerant traders, was, at times, politicized and problematized, with central and local authorities taking on different roles. Finally, it demonstrates that Gypsies were an integral part of the Bahian social universe, that they were often protected and sponsored by local elites, and that social opportunities influenced how authorities viewed them. With the exception of the first half of the eighteenth century, between the late sixteenth and late nineteenth centuries, the central authorities were ambivalent about Gypsies in Brazil. They were largely officially ignored at all levels of power. Nevertheless, a longer-term look reveals not a coherent policy as such, but sporadic attempts to discipline them. In some cases, landowners and their hired guns, along with city administrations and their police forces, harassed, chased, and even killed Gypsies. In others, local authorities appealed to the central powers for support against what they perceived as a Gypsy threat. Within the official perspective, Gypsies marked the limits of the proper social order and served, as in Patroni's case, to highlight elite visions of society and to justify state interventions. The figure of the Gypsy thus speaks of contemporary social conflicts, state-building processes, and the attitudes of authorities towards the povo in general.

METHOD AND SOURCES

This article focuses on Bahia, a state in north-eastern Brazil, between the late sixteenth century and the early twentieth century. It is based on four kinds of sources: archival sources, in particular, documents collected at the Arquivo Público do Estado da Bahia (APEB); edited primary sources such as those organized in the annals of the National Library of Brazil; primary sources including, for instance, the above-mentioned Patroni's travel account; and secondary sources.

The historical position of Bahia and, in particular, its capital, Salvador, makes it possible to outline actions taken by authorities at all levels of power in relation to the Gypsies. A commercial centre and a port, Salvador was one of the most important cities in the Portuguese empire; in the mid-eighteenth century, it was the second largest city, after Lisbon. The first bishopric in Portuguese America was established there, and it was the seat of the governors-general and of the high court in Brazil until these moved to Rio de Janeiro in the second half of the eighteenth century. Accounts of Gypsies in Bahia go back to the earliest days of Portuguese settlement. The first mention of Gypsies in Brazil is related to this province and dates from the end of the sixteenth century. Salvador was among the ports that received Gypsies banished to overseas colonies by the Crown; Santo António Além do Carmo, a neighbourhood where some Gypsies were made to settle at the beginning of the eighteenth century, was inhabited by them for at least the following two hundred years.

I complement Bahia-related sources with those related to other states, especially those in north-eastern Brazil. Views of Gypsies and their day-to-day interactions with non-Gypsies were comparable across the region.Footnote 5 In the early eighteenth century, municipal councils of the coastal sugar-producing cities of the north-east, such as Olinda in Pernambuco and Salvador in Bahia, problematized Gypsies in an identical manner. The sertão, the semi-arid backlands, which stretches through the interior region of seven north-eastern states, was itself sparsely populated by a mobile population that disregarded provincial boundaries. Accounts of several foreign travellers and memoirs of Brazilian intellectuals from the nineteenth century are particularly revealing since they contain occasional observations on Gypsies in the sertão and provide glimpses into Gypsies’ way of life and interactions with other Brazilians; I draw on them to sketch a picture of their insertion into Brazilian society.

I translate the term Cigano (sometimes written Sigano) as “Gypsy”. But to what extent can I link the Ciganos of previous centuries as they are categorized in official documents of the period to contemporary Brazilian Romanies, for whom Cigano is a term of present-day political recognition? For a few Calon families in Rio de Janeiro, such continuity is,Footnote 6 or was in the past,Footnote 7 a part of these families’ histories. But one cannot generalize from these cases. It is clear, however, that since I am dealing with imposed identities and representations produced by authorities and elites, there is a danger of reification when extrapolating from them anything about Gypsies and their way of life.Footnote 8 Eighteenth-century royal edicts, for instance, posited only a thin boundary between the category of “Gypsy” and those categorized as leading Gypsy-like lives. A similar limitation arises in the writings of nineteenth-century observers, who often said little of the criteria they used in order to identify Gypsies.Footnote 9 For example, Augusto Zaluar (1826–1882), a Brazilian writer who set out with an explicit intention to “catalogue the civilizing elements” of the Brazilian nation,Footnote 10 was accused by his friend and editor, Affonso Taunay, of mistaking a camp of caboclos Footnote 11 living in huts along the road for Gypsies.Footnote 12 As anthropologist Felte Bezerra observed in 1950, “among us, a Gypsy carries a cultural rather than ethnic meaning, and designates a nomadic lifestyle sustained through exchanges and trade”.Footnote 13

One has to remember, then, that this article discusses officially imposed identities created in order to deal with those categorized as Ciganos. The long-term view adopted here enables recognition of the continuities and changes in such categorizations, of common features with developments elsewhere, and of Bahian and Brazilian specificities.

EMERGENCE OF CIGANOS IN BRAZIL

The first Gypsy commonly linked by scholars to Brazil was João Torres, who was banished to the country in 1574, although there is no record that he ever arrived.Footnote 14 The earliest names of Gypsies residing in Bahia come from the records of the First Visit of the Holy Office (1591–1592). Eight Gypsy women figure in seven denunciations as both denounced (six cases) and denouncers (five cases);Footnote 15 an additional woman confessed to blasphemy within a “period of grace”.Footnote 16 Of the six cases in which the Gypsy women stood accused, four concerned Violante Fernandes, who was denounced for various blasphemies. Other Gypsy women were accused of sorcery, renouncing God, or denying Judgement Day.

Documents of the Portuguese Inquisition reveal some things about the lives of these Gypsy women and of how the Crown dealt with their kind. All the Gypsies mentioned are listed as being born in either Spain or Portugal and all but one of the women was married to a Gypsy.Footnote 17 Some earned their living as peddlers, while one couple served as jailers. Since four of the seven denunciations were levelled by a Gypsy woman against another, one can also speculate about the intensity of relations among Gypsies in Salvador at the time. For example, two of the women, Tareja and Angelina, claim to have witnessed Violante blaspheming while peddling with her, while Brianda accuses another Gypsy woman, Joanna Ribeiro, of taking the placenta of her (Brianda's) newborn when visiting her after the delivery, then salting it and hiding it in a wardrobe, a procedure that apparently killed the baby. There seems to be some sort of campaign against Maria (Violante) Fernandes. Whether this was because she was particularly disliked, an easy target for a community under pressure, or for another reason, remains obscure, for now at least, but the fact is that of the four cases listed in the book of denunciations in which a Gypsy woman accused another, three were against Violante; a further accusation was made against her by an official of the ecclesiastical court who was told about Violante's blasphemy by Tareja (who heard it from Angelina).

We do not know what proportion of the population the Salvador Gypsies constituted at the time. The frequency of their occurrence in the Inquisition records for Bahia is about two per cent.Footnote 18 Nevertheless, the records bring to light some aspects of the colonial politics of difference and racialization of Gypsies. People are classified as Old, New, or Semi-New Christians; controlling the religious practices of the Jewish converts (the New Christians) exiled to the colonies was the prime motivation for the Inquisition's visit. Places of birth are recorded; some of the Gypsy women were born in Spain. Lastly, in about ten per cent of all cases, “race” (raça) is given, with “cigano” being the only such “race” specified for Old Christians born in Portugal.Footnote 19

In Portugal, in the sixteenth century, the category of Ciganos emerges from a variety of sources: foreign traders sometimes accused of fraudulent behaviour; vagrants (vadios) without stable employment; or masterless men who gained a living through negotiation or theft. Although the Royal Charter of 1526 and a law introduced in 1538 called for the expulsion of all Gypsies from the kingdom, and although the latter makes a distinction between Gypsies and those “who wander like Gypsies: since they are not”, but are, rather, “natives of the kingdom”,Footnote 20 subsequent legislation distinguished between native Gypsies, foreign-born Gypsies and those seen as leading Gypsy-like lives.

The term “Gypsy” starts to denote specific habits and a way of life, and as their relationship to the centres of power – the Crown and the Church – became increasingly problematic, Gypsies and those accused of leading Gypsy-like lifestyles began to be exiled overseas.Footnote 21 This is also evident from the Bahian Inquisition records. Violante Fernandes (a daughter of a non-Gypsy Portuguese father and a Gypsy mother) and Apolonia de Bustamãte (born in Spain) had been deported for stealing animals;Footnote 22 another woman, Tareja Rois, is recorded emphasizing that she had come to Brazil of her own volition.Footnote 23 In Bahia, Gypsies do not seem to have been particularly targeted by the Inquisition, and there is nothing that would suggest any association with the magical practices specific to Gypsy women; rather, the cases reflect the popular religiosity in the colony that preoccupied the authorities.Footnote 24 The majority of the accusations concerned blasphemy, were not made by non-Gypsies, and there is no mention of palmistry (buena-dicha), a practice that, along with language and wandering habits, was marked by authorities in Portugal as being undesirable.

POPULATING BRAZIL, WARNING THE CITIZENS

The system of degredos – royal edicts of the sixteenth to eighteenth century by which people were sentenced to work on galleys or banished to colonies – is evidence of the authorities’ views of Gypsies that were emerging at the time. It is also an outcome of their preoccupations with Portugal's underpopulation and the quality of its population. Although the empire needed explorers and inhabitants, not everybody could be allowed to leave freely to the colonies, while those who stayed were expected to be as productive as possible. Hence, “[t]he small demographic base and global requirements translated into a reality that each and every citizen was simply too valuable to waste”.Footnote 25 By using degredados (convict exiles) – prostitutes, orphans, major and minor criminals, New Christians, and Gypsies – it was possible to populate the colonies in a relatively controlled manner and, at the same time, make it clear to those who remained in Portugal what was expected of the Crown's subjects in the early modern state.

Within a century of the first official mention of Gypsies in Portugal, degredos became part of an attempt to expel them from the realm and discipline those categorized as Gypsies or as leading Gypsy-like lives.Footnote 26 Already, the above-mentioned 1538 law banished to African colonies those Portuguese subjects accused of the latter. Degredos would normally expel foreign Gypsies from the kingdom, while Portuguese Gypsies were offered the choice of giving up their lifestyle or to be banished to colonies. Changes within individual colonies (the goal of definitive colonization of north-eastern Brazil, the growth of the sugar economy and mining in Brazil) and of relationships between them (the slave trade from Angola was in place by that time) had also affected the treatment of Gypsies. Thus, over time, destinations for deportations changed, and around 1686, with the opening of the Brazilian hinterland, Ceará and Maranhão replaced Africa as the main port of call.

Most edicts dealt with men and women differently. For example, according to the edict from 1592 (i.e. around the time of the Holy Office's visit to Bahia), Gypsy males were to leave the country or be sent to galleys while women were to give up Gypsy “habits” and language or be exiled to Brazil for life.Footnote 27 The Bahian Inquisition records give a sense of the consequences exile had for individuals and for conjugal relations: one man, living in Salvador, was rumoured to have a wife somewhere else; at least two women had been separated from the Gypsy men they had lived with in Portugal; and Violante claimed to be a widow but reportedly had a husband in the galleys.Footnote 28

Degredos targeted Gypsy life and customs.Footnote 29 However, as was the case with degredos in general, besides the expulsion of undesirables from Portugal, the legislation was also aimed at disciplining the population remaining within the kingdom's borders. This population control tightened after the War of Restoration (1640–1668), when diminishing charitable resources, concerns about public safety and criminality, and economic recession made Gypsies “obvious and non-controversial subjects of social control”.Footnote 30 In the long run, this legislation also helped reify an image of Gypsies as different and associated with socially undesirable practices and characteristics – what Donovan describes as “social deviance”.Footnote 31 In a law of 1708, for example, Gypsies were accused of frequent theft and deceit (engano). Like previous regulations, the law stipulated a punishment of galley service for men and exile to Brazil for women, both for a period of ten years; this applied to “those behaving as Gypsies” and to “those associating with them”, as well as to Gypsies themselves, unless they gave up wearing Gypsy clothes, speaking Gypsy languages, practising palmistry, living together, working together, and trading with beasts of burden.Footnote 32

The number of legislative measures passed in the seventeenth century with the aim of expelling Gypsies from the kingdom testifies to their ineffectiveness, a fact explicitly recognized in a law introduced by the new king, João V, in 1708.Footnote 33 While this might suggest the non-cooperation of local authorities, it is also revealing of a certain exemplarity – the repetition of decrees against Gypsies and against those leading Gypsy-like lives served as a warning to the population and a way to foreground the desirable characteristics of citizens. Be that as it may, in February 1718, King João V ordered that all Gypsies along the Portuguese borders with Spain be imprisoned and deported.Footnote 34 This time, whole families and communities were to be rounded up and no alternatives to exile were offered. As a result of this campaign, on 10 March 1718, the Gazeta de Lisboa reported that fifty men, fifty-one women, and forty-three children were imprisoned in Limoeiro.Footnote 35 Their deportation was heavily publicized and, in combination with the usual spectacle offered by the departure and arrival of ships, served as a demonstration of the king's will.Footnote 36

Mass deportations continued throughout the century, although their scope and frequency has yet to be assessed. The last known shipments from Portugal to Brazil – which comprised some 400 Gypsies – occurred in 1780 and 1786.Footnote 37 The total number of individuals exiled as Gypsies to Brazil is impossible to estimate, as many of the ship registers have since been lost. The Public Archive of Bahia holds two name registers of Gypsies arriving in Salvador, one detailing five Gypsy couples and their children who were brought by ship to Bahia in 1718,Footnote 38 and the other covering eleven Gypsy couples without children on their way to Angola in 1756.Footnote 39 A letter dated 11 April 1718 accompanies the 1718 register. Addressed to the governor of Bahia, it states that shipments of Gypsy families to Salvador would continue, due to their “scandalous behaviour” within the kingdom.Footnote 40 The letter ordered that, in Bahia, they would be prohibited from using their own language and that the governor was to ensure that it was not taught to children; the same letter was sent to the governors of Rio de Janeiro, Pernambuco, Paraiba, Angola, Cape Verde, and São Tomé.Footnote 41

ENFORCING THE REGULARITY THAT THE LAW DICTATES

In July 1719, only a year after the spectacle of the deportation from Lisbon, the governor of Bahia ordered all captains to capture, “without hesitation or any dodging”, three Gypsy men who had deserted Salvador and a Gypsy woman who was the mother-in-law of one of them.Footnote 42 In August of the same year, the governor sent another, similar letter, and in November, he ordered the captains to imprison “discreetly” and “with diligence” all Gypsies, men and women, old and young.Footnote 43 After the silence about Gypsies of more than a hundred years in the archival sources pertaining to Bahia, these orders betray an increasing preoccupation caused by the deportation of Gypsies to different Brazilian cities. After all, these new arrivals required employment (in the above case as soldiers), policing, and a place to live, compounded by the fact that, officially, Gypsies were prohibited from leaving Salvador.

According to a letter from the viceroy of Brazil dated 1755, Gypsies exiled to Salvador had settled in the quarter called Bairro da Palma, which became known as Mouraria (the place of the Moors), but as their population grew, they were allowed to settle in the neighbourhood of Santo António Além do Carmo as well as throughout the Recôncavo, an area around the Bay of All Saints.Footnote 44 The letter was an opinion solicited by the Conselho Ultramarino (Overseas Council) following a written complaint by the municipal council of Salvador dated 5 July 1755; a similar complaint was issued by the council in Cachoeira, the sugar-producing and commercial centre of the Recôncavo.Footnote 45 Both municipal councils pleaded with the king to “free them” of these “damned people”, who traded with horses and encouraged slaves to steal from their masters. The main complaint of the two letters, however, was of the Gypsies’ theft of horses from caravans coming from Minas.Footnote 46

The petitions from local councils to the central authorities have to be seen in the context of both the preoccupation with public safety and the importance of mining for the kingdom. Gold was discovered in Minas in 1695 and although Gypsies were officially prohibited from entering Minas,Footnote 47 they started arriving there as early as the 1720s, often after being expelled by Bahian authorities.Footnote 48 The sertão, through which the caravans had to pass on their way from Minas to the coast, remained a violent place throughout the eighteenth century. Authorities blamed disorder on the “bad quality of the population”.Footnote 49 The discovery of gold also precipitated a tightening of direct Portuguese rule, with bureaucrats and soldiers sent to control mining, inhibit smuggling, and collect taxes on the gold extracted. Regulations dealing with Gypsies, especially those aimed at expelling them from Minas, were therefore a part of the effort to control Brazilian people viewed as “unruly” and “mobile”,Footnote 50 of which Gypsies were a visible segment.Footnote 51 Some contemporaries recognized that the role of Gypsies was exaggerated: in a letter to the governor of Minas in 1737, a captain of dragoons explained that he was not going after certain Gypsy fugitives because it was not worth following “ten or twelve Ciganos” and lose a horse in the effort, since “none of them had committed any crime other than the misfortune of being a Gypsy, accustomed to an irregular life (uma vida irregular)”; that is, one that does not conform to established laws or customs.Footnote 52

Common complaints against Gypsies included their carrying of weapons, stealing slaves and animals, and being salteadores dos caminhos (highwaymen), an accusation that after 1766 could be applied to anybody caught wandering through the sertão.Footnote 53 Prompted by the letters from Salvador and other colonial authorities, on 20 September 1760, King José I passed a charter in which he specified how “such useless and coarse people” should be made to take up “civilized lives”. The king ordered small boys to be handed over to craftsmen and men to become soldiers or find employment in public works. Gypsies were not permitted to wander, carry arms, live together in one neighbourhood, or trade in slaves or beasts of burden. Those who broke this law were to be summarily deported to São Tomé and Príncipe.Footnote 54

In August 1961, the interim governors of Bahia reported that before it was possible to implement the king's law, which would “give them regularity”, Gypsies had abandoned Bahian towns, but they also presented measures they planned to undertake so that the law would be enforced and Gypsies compelled to devote themselves to agriculture or wage labour.Footnote 55 In October 1761, they reported that “Gypsies want to take up ordered lives (vida regulada), because they are being imprisoned all over the country. [They wish to] totally give up their illicit trade and libertine way of life”. The governors admitted, however, that boys were rarely handed over to craftsmen because they married very early.Footnote 56

ITINERANT TRADERS AND SOCIAL ORDER

The sources reviewed so far deal with the criminalization and disciplining of Gypsies as representatives of the unruly povo, of undesirable lifestyles and strange customs, all of which could be eliminated with their assimilation, through employment, settlement, and breaking up the communities. A closer look at Gypsies’ day-to-day interactions, however, reveals a more positive, albeit ambiguous, insertion into the Brazilian social fabric. This, at least, is what seems to emerge from writings of Brazilian memoirists and foreign travellers, who, beginning in the early nineteenth century, made several observations about Gypsies and their lives. Travelling through Pernambuco in the late 1830s, George Gardner noted:

[Gypsies] seldom come near the large towns on the coast, preferring more thinly inhabited, and consequently more lawless districts; they wander from farm to farm, and from village to village, buying, selling, and exchanging horses and various articles of jewellery; like those of Europe they are often accused of stealing horses, fowls, or whatever they can lay their hands upon; the old women tell fortunes, in which they are much encouraged by the young ladies of the places they visit. Although they speak Portuguese like the other inhabitants of the country, among themselves they always make use of their own language, always intermarry, are said to pay no attention to the religious observances of the country, nor to use any form of worship of their own.Footnote 57

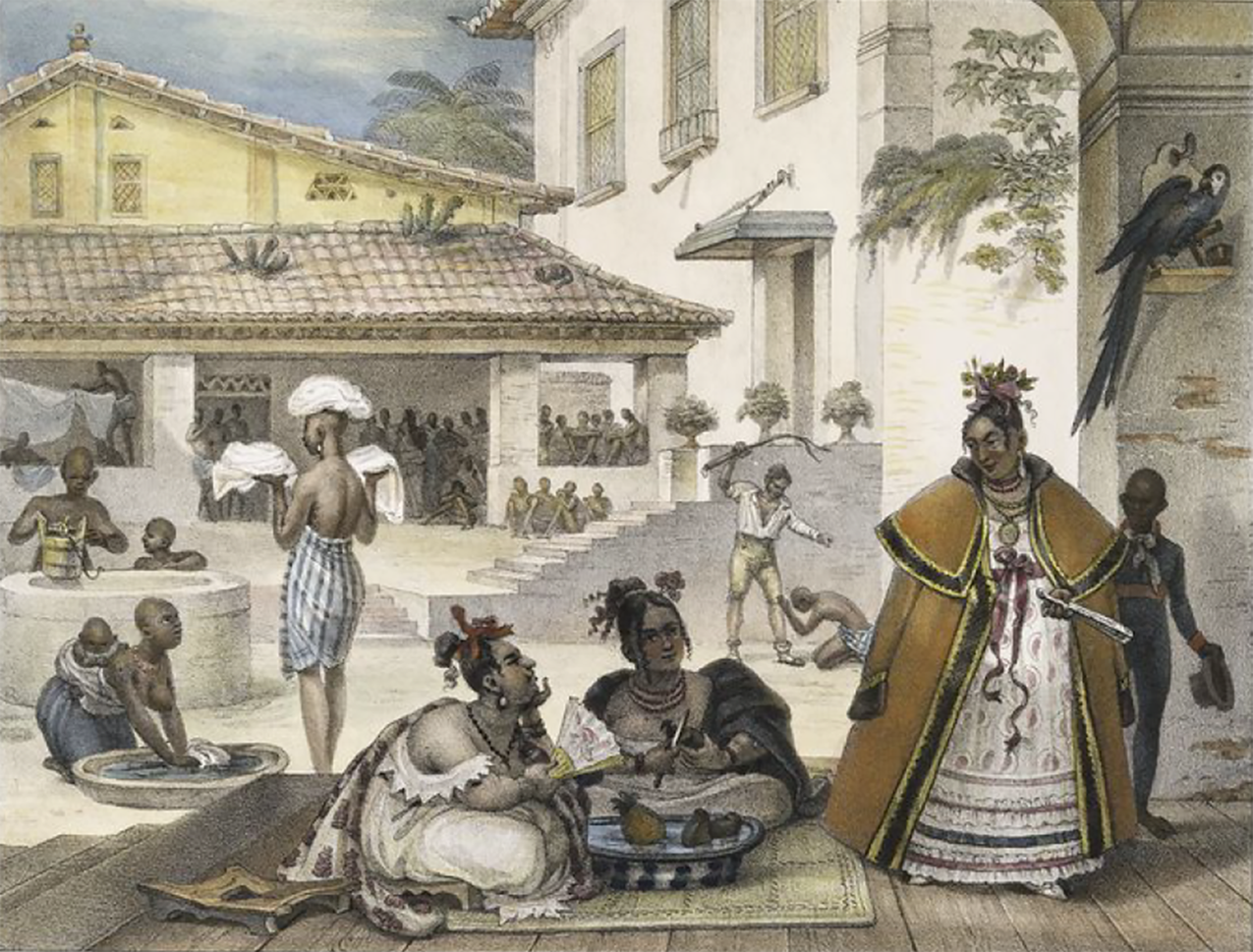

In 1866, Sir Richard Burton, a Victorian traveller, spent a night in a Gypsy tent, while, three decades before him, Jean-Baptiste Debret, a French painter, depicted the interior of the house of a rich Gypsy trader of enslaved Africans and provided an accompanying commentary (see Figure 1).Footnote 58 The two modalities were not separate: in the letter from August 1761 cited above, the Bahian interim governors wrote that the Gypsies lived in “set-apart neighbourhoods” and were “used to leaving their houses often and going bartering and trading throughout the sertão”. Lady Callcot, a British writer of travel books, after visiting Botafogo in Rio de Janeiro in the early 1820s (then a village inhabited only by “fishermen and gipsies [sic]”), wrote that “part of their [Gypsies’] families is generally resident at their settlements but the men rove about the country and are the great horse jockies [sic] of this part of Brazil”.Footnote 59 Travelling through Minas Gerais in the late 1880s, an American civil engineer, James Wells, bought mules from a settled Gypsy who owned a farm that his relatives, mobile animal drovers, were using for temporary encampment.Footnote 60

Figure 1. “Plate 24: Intérieur d'une habitation de Ciganos (Bohémiens)”, in Debret, Voyage pittoresque et historique. An extract of the accompanying commentary (pp. 80–82) reads: “Women are generally well treated by their husbands, and are reluctant to marry into another caste, in order to avoid the contempt or hatred of their relatives. […] Among Gypsies, women, although coquettish, are generally chaste, but less out of virtue than out of fear of revenge and the execution of their caste. […] Bachelors respect married women, and seek out free mulattas and negresses. […] Proud of their wealth, they spend considerable sums on jewellery; but, exposed due to their lowliness to frequent persecutions, they possess only very simple furniture, usually composed of a few trunks and a hammock, indispensable objects that are not obtrusive in the case of emergency relocations.”

Gypsies composed sedentary or peripatetic groupings of different sizes, ranging from a few families to more than 500 individuals.Footnote 61 Occasionally, when they encamped close to towns, they were accused of disturbing public order or of stealing slaves and animals and chased away. In 1726, Gypsies were given twenty-four hours to leave the city of São Paulo, after being deemed “harmful to the population because they walked around organizing games and other disturbances”.Footnote 62 A year later, the bishop of Rio de Janeiro complained of Gypsies in Minas “performing immoral operas and comedies that insult the sacred teachings of the Holy Church”.Footnote 63 The Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre talks of Gypsy circuses with bears (“real and fake”), monkeys, and boys (“sometimes abducted”) doing acrobatics on horses (“generally also stolen”).Footnote 64

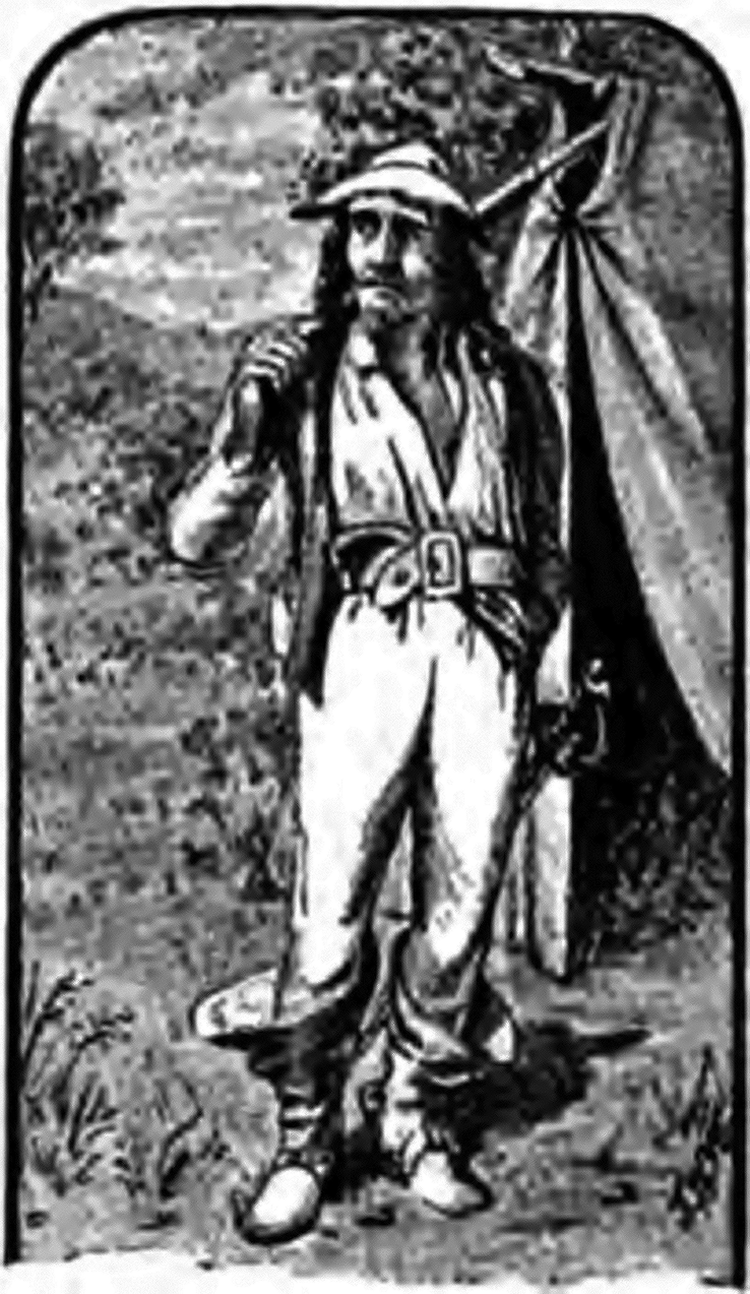

In the nineteenth century, Gypsies were thus known as entertainers, coppersmiths, and palmists, but primarily as itinerant traders (see Figure 2). Dispersed peasant and mining communities and self-subsistent fazendas hampered the development of fixed trading establishments.Footnote 65 According to some commentators, Gypsies were the first “gringos”, a term originally used in the north-east for itinerant traders of non-Portuguese origin.Footnote 66 As early as 1591, the Holy Office described Gypsy women as ambulant vendors working throughout Recôncavo Baiano, and the August 1761 letter by the governors of Bahia states that Gypsies are used to leaving their houses located in peripheral neighbourhoods in order to “barter and trade throughout the backlands”.

Figure 2. “A Brazilian gypsy” in Wells, Exploring and Travelling, p. 378. The text (pp. 379–384) that this picture illustrates states: “Most of them [Ciganos] were really handsome fellows, with dark olive complexions, bright keen black eyes, good features, long glossy black hair hanging in greasy ringlets that reached to their shoulders; some were dressed in tanned deer-skin suits, others in the ordinary coarse cotton costume of the country. All were well armed with long pistols (garouches); others also carried carbines, knives, and sabres. […] [Several] had just arrived from a long journey from São Paulo, where they had been purchasing mules, and were then taking them to Bahia for sale, or any place along the way. […] The tribe consisted of about fifty men and women, and several children.”

Authorities were ambivalent about ambulant traders in general, sometimes praising them as agents of civilization, at other times accusing them of abusing people's poverty and ignorance or blaming them for breaching the peace.Footnote 67 Outside the large cities, Gypsies, as suppliers of goods, animals, and slaves, were often tolerated by the wealthy, whose protection they sought out. Patroni's recollections of his encounter with Gypsies in Ceará in 1829, with which I started this article, is testimony to this: thinking that he was about to be assaulted, Patroni told the Gypsies that he was a judge; immediately, “all of them began to salute me with bows, and pleaded that I provide them with patronage in the town of Icó, where they were going to trade”.Footnote 68 Ten years later, George Gardner encountered Gypsies between Ceará and Pernambuco and noted that they “are generally disliked by common people, but are encouraged by the more wealthy, as was the case on the present occasion for they were encamped beneath some large trees near the house of a major in the National Guards, who is the proprietor of a large cane plantation”.Footnote 69

Itinerant traders and, in particular, Gypsies, although crucial for the functioning of the internal economy, were viewed with suspicion by most people. According to Burton, “the peasantry regard them with disgust and religious dread”.Footnote 70 Other observers reported that people considered Gypsies’ goods to be stolen, overpriced, or of low quality, or suspected them of double-dealing.Footnote 71 This sometimes turned out to be just baseless accusation, as Gardner's experiences demonstrate.Footnote 72 Jean-Baptiste Debret (see Figure 3) gives this advice when buying from Gypsy slave traders in Rio de Janeiro: “they do not lag behind their kinsmen who trade with horses; therefore, whenever one wants to buy a Negro in one of these establishments, one has to take precautions and bring along a surgeon [to examine the slave]”.Footnote 73

Figure 3. “Plate 23: Boutique de la rue du Val-Longo”, in Debret, Voyage pittoresque et historique. The accompanying commentary (pp. 78–79) reads: “I reproduced here a sales scene. We can see, in the arrangement of the shop, the simplicity of the furniture of a Gypsy, a second-hand seller of negroes, [that he is] of mediocre fortune. […] At this point in time, the negroes deposited there belong to two different owners. The colour of the fabrics that cover them distinguishes them; one is yellow, and the other is dark red. […] A Mineiro [a man from Minas Gerais] haggles over one slave with the Gypsy who is sitting in his chair. […] The neglected clothing of the merchant corresponds to the coarseness of his morals; he also suffers, judging by the discoloured complexion and swelling of his stomach, from the [intestinal] obstruction that he brought from the African coast, which is so disease-filled that foreign troops can hardly remain there for more than three years without being in need of being replaced by others who are healthier.”

Freyre's remarks that boys performing in Gypsy circuses had been abducted also shows that, besides typical accusations of animal and slave theft, Brazilians shared more the established Iberian stereotype of Gypsies as baby-snatchers. Like other “translocal attributes” of Gypsies, “in each culture where it surfaces, the stereotype of the Gypsy baby thief responded to particular configurations of power and stages of national development”.Footnote 74 Gypsies traded in slaves and people sought out Gypsy spells when looking for runaway slaves.Footnote 75 At the same time, Gypsies were often accused of kidnapping freemen and selling them into slavery, of buying children stolen by fugitive slaves from their former masters, and of supplying quilombos (maroon communities founded by enslaved Africans and their descendants who escaped from slavery). An official investigation of a quilombo near Recife, Pernambuco, revealed that weapons of the kind used by the army had been supplied by a Gypsy named Genoíno Dantas; he also allegedly resold runaway slaves instead of returning them to their rightful owners.Footnote 76 When a quilombo in Abrantes near Salvador was destroyed in 1827, one of the reasons given against its inhabitants was that the maroons were getting their revenge by stealing the children of their former masters and selling them to Gypsies.Footnote 77

In other words, because Gypsies crossed the boundaries of this predatory economic system and in various ways served as its conduits, they threatened to subvert its racial hierarchies and expose its contradictions.Footnote 78 Thus, in nineteenth-century Brazil, the trope of the Gypsy baby-snatcher reflected not only their ambiguous position, recognizable from other parts of the world, but also concrete popular misgivings, especially around familial and sexual life under slavery. As Robert Walsh, a chaplain to the British Embassy, apparently observed in Brazil in the 1830s, those purchasing enslaved individuals were greatly disturbed by the more white-looking children on sale.Footnote 79

ELITE ENTERTAINERS OR VAGRANTS?

Bill Donovan argues that when Gypsies moved from Portugal to Brazil the perception of Gypsy social deviance changed from that which viewed them as social pariahs to one that saw them instead as a stigmatized minority in the periphery.Footnote 80 He substantiates this argument by describing a shift in the treatment of Gypsies by the respective authorities: while in the late seventeenth century and eighteenth century in Portugal a series of royal edicts banished Gypsies as undesirables to the colonies, in nineteenth-century Brazil their distinctiveness became unimportant and their economic activities socially accepted. The context of slavery and the complexity of Brazilian race relations (and the social tensions both of these created) led to the obviation of ethnic fault lines, with Gypsies beginning to be seen as belonging to a broader category of poor people of European origin. Gypsies’ role in internal commerce placed them alongside many intermediaries without whom the economy would not have functioned.

Donovan's evidence is skewed towards Rio de Janeiro between the establishment of the Royal Court in 1807 and the closing down of Valongo, the main slave market, in 1831. The Gypsies of Rio de Janeiro were known primarily as comissários, who moved slaves on behalf of others, and as small-scale traders and resellers of slaves.Footnote 81 They were associated with Valongo, which consisted then of about fifty establishments, many run by Gypsies, each of which contained about 300 to 400 slaves.Footnote 82 Some Gypsies also served as meirinhos (lower court officials)Footnote 83 and several Gypsy families were wealthy and socialized with the elite. A Gypsy moneylender named José Rabello was reportedly one of the wealthiest men in the city; he also received an honorary military title.Footnote 84 Baron von Eschwege, a German geologist and mine engineer, described Gypsy performances during festivities for the wedding of the Don Pedro Carlos, Infante of Spain and Portugal, and his cousin Maria Teresa, Princess of Beira, in May 1810.Footnote 85 And to celebrate the elevation of Brazil to the status of kingdom in 1815, João VI, accompanied by his entire court and numerous foreign delegates, spent an evening of merrymaking in the Campo dos Ciganos, Rio's Gypsy neighbourhood.Footnote 86

Donovan interprets these as signs that the social and economic conditions in Brazil, in conjunction with the specificities of its racial regime, opened a social place for Gypsies that differed, at least temporarily, from that of social deviants in eighteenth-century Portugal. The picture is not unequivocal, however, since increased visibility, exoticization, and insertion into the slave economy in the early nineteenth century did not benefit all Gypsies, even in Rio de Janeiro. For example, describing the Gypsy community in Rio de Janeiro in the first half of the nineteenth century, Mello Moraes Filho, a Brazilian folklorist, reports of poor Gypsies making their livelihood through beggingFootnote 87 and of successful Gypsy families distancing themselves from those who “infested the roads”, that is those commonly accused of highway crime.Footnote 88

In Rio de Janeiro, Gypsies, along with freedmen, were the main suspects in cases of such crimes and slave theft.Footnote 89 In the 1830s, the authorities were growing increasingly concerned with the increase in thefts and illegal transactions involving enslaved persons, and Gypsies and bounty hunters were “were the first to be suspected when a theft was discovered or made public”.Footnote 90 Gypsies were accused of kidnapping slaves, often through seducing them, sometimes with a help of their own slaves;Footnote 91 of buying stolen slaves from gangs of freedmen; of selling runaway slaves that they received from bounty hunters (mostly freed blacks and mulattoes); of kidnapping freemen and turning them into slaves; and of transporting stolen slaves outside the city.Footnote 92 An anonymous letter sent to the chief of Rio's police force in 1834 claimed that one such Gypsy gang was “protected by persons of high esteem”.Footnote 93

The situation in the north-east was even more different. Henry Koster, an Englishman born in Portugal, who lived in the state of Pernambuco between 1809 and 1815, explains that he had never met any Gypsies because “the late governor of the province was inimical to them, and some attempts having been made to apprehend some of them, their visits were discontinued”.Footnote 94 On an imaginary line of continuity from social outcasts to a stigmatized yet tolerated minority, this suggests something closer to the former, although unlike in seventeenth-century Portugal, persecution and pressure towards assimilation is not orchestrated by the central authorities.

In Bahia, meanwhile, food crises, federalist revolts, and slave rebellions led to concerns over public safety. The case of the quilombo in Abrantes, mentioned earlier, and the related public panic over runaway slaves selling the children of their former masters to Gypsies, is one example of the effect of social conflicts on the perception of Gypsies. Another is provided by the Bahian historian Castelluci Junior, who describes the impact of an 1831 gathering of judges, who, coming from several towns in southern Recôncavo, elaborated a new legal code that was intended to help in catching runaway slaves and criminals and in disciplining vagrants (vadios).Footnote 95 Passports were issued to control people's movements and to prevent both the kidnapping and the fleeing of enslaved individuals. The code also elaborated regulations against Gypsies, including punishments for Gypsies without employment and farmers who let Gypsies camp on their land. In 1833, José de Palma, a Gypsy resident of Santo António Além do Carmo, Salvador, was charged under these regulations while trying to deliver four slaves to a customer in Jaguaripe. Lacking passports for the slaves, he was subsequently imprisoned. Further investigation revealed that he had not paid tax on the slaves and that one of the slaves had been stolen and sold to him by kidnappers.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, besides continued accusations of theft, Gypsies in Brazil were targeted as a part of the fight against vadiagem (vagrancy), which became a crime under the new Royal Criminal Code of 1831. They were seen to belong to a class of non-working free people – malandros (rascals), vadios (vagabonds), moleques (street children living off petty theft), capoeiras (free negro highwaymen hiding in the capoeira forest), and so on – feared for their criminality and rebelliousness.Footnote 96

By highlighting the character of Gypsy integration in the societies in which they lived, the economic structure of these societies, and the social taxonomies into which perceptions of social deviance fit, Donovan makes an important point that the position of the Gypsies has to be interpreted from within its regional and historical context. Even in nineteenth-century Rio de Janeiro, the romantic valorization by the elites, including the royal family, and the social mobility of some individuals and families did not, however, prevent preoccupations with Gypsies by the police and regional authorities, which demonstrates continuities with the past.

BUILDING NATIONAL FUTURES

While there is information about Gypsies from the first decades of the nineteenth century, in the second-third of the nineteenth century, the category of the Cigano appears only infrequently. It reappears towards the end of the century and a concern with Gypsies lasts until the second decade of the twentieth century. During this period, Brazilian elites set their eyes upon civilizing the country, a state-building project which was conceived in racial terms.Footnote 97 Racial theories enabled intellectuals and politicians to implement a conservative programme that justified differential citizenship within a liberal and republican framework.

During this period, authorities submitted the poor to greater rigorous control, in Bahia particularly through the repression of begging and loitering and through the physical reorganization of public spaces.Footnote 98 In this process, the already established concept of vadiagem was further elaborated and expanded in connection with two modernization projects. First, there were the hygienization and public health concerns that arose alongside ideas of modern urban planning.Footnote 99 In Bahia, concerns about sanitation and preventing epidemics was used as a justification of attempts at improving the quality of the povo. Although Gypsies were peripheral to discussions about racial degeneracy that consistently drew on racial theories that established links between race and disease, they were sometimes deemed as the cause behind some specific ills, such as trachoma.Footnote 100

The second, and interlinked, modernization project concerned the disciplining of the labour force and redefinition of work necessitated by the end of slavery. The question for white elites was how to secure labour for their plantations, and a series of vagrancy laws and police harassment became the main method of disciplining the recently freed people, in particular.Footnote 101 Gypsies, commonly viewed as leading itinerant and non-productive lives, became visible once again and their lifestyle problematized. As early as 1858, a municipal regulation in Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais, which regulated begging, specifically prohibited Gypsies from staying in the city for longer than twenty-four hours and the city's inhabitants from trading with Gypsies. Both the police and public hygiene authorities were responsible for the implementation of this regulation.Footnote 102 Although Juiz de Fora was a special case of a modernizing town undergoing rapid industrialization, the strategies employed there were similar to those seen in Bahia.

In the eyes of urban elites concerned with Brazil's backwardness, the Gypsy lifestyle emerged incompatible with progress. The Bahian newspapers that started to appear around this time elucidate these views thanks to their role in contemporary processes of political and cultural transformation. In Bahia, as elsewhere in Brazil, newspapers provided a novel source of information and insight, and through amplifying political, medico-hygienist, and other discourses, they served as vehicles of modernization, promoters of republican conceptions of the state, and tools for reordering social life in accordance with contemporary ideas about race. It is worth noting that Patroni, whom we encountered in this article's introduction, founded the first newspaper in the province of Grão-Pará. In Bahia, at the beginning of the twentieth century, newspapers reported on the movements of Gypsy “hordes”Footnote 103 and on police actions against themFootnote 104 – even encouraging the police to go after GypsiesFootnote 105 and praising them for their successes.Footnote 106 They also reported on the latest developments in science (including eugenics) and fought superstition by detailing Gypsy tricks.Footnote 107

This overview indicates how a combination of concerns about the quality of the povo and its racial degeneracy, and about public safety, labour discipline, and political stability resulted in the heightened visibility and harassment of Gypsies during the period from the passage of the Law of the Free Womb in 1871 to the end of the First Republic in 1930. While it must remain a theme for another paper, it is safe to say that this particular period was moved for the Gypsies of Bahia.Footnote 108

BAHIAN LESSONS

Vast areas of Brazil were subject to only weak central governmental control and local development depended on the personal aptitude of state representatives on the one hand and local power holders on the other. The authorities’ treatment and representation of Gypsies differed across periods and between regions, but the long-term view allows us to distinguish specific tendencies and trace changes and continuities over time. Beyond adding another case study to Romani-related historiography, it also brings to sharp relief certain dynamics that are less visible when looking at European societies. First, it substantiates Lucassen's argument that Gypsies present “a useful critical case to render state actions extremely visible”Footnote 109 as it reveals the complexity of interactions between multiple levels and kinds of authorities. There was not a one-sided entry of the state and its apparatus, informed by modern ideas about society; rather, “[t]he process of criminalisation and legibility preceded this change”,Footnote 110 with “the loop from local to central and back to local”.Footnote 111 This is true of imperial states as well as of nation states and the Bahian case corroborates the necessity to look at the complexity of interactions between various levels of state power. Bahian cities in the eighteenth century demanded that the Crown regulate the lives of the Gypsies exiled to its colonies. Moreover, one cannot understand the situation in one locale without taking into account developments in others. Responding to the 1724 complaint by the city of Olinda, Pernambuco, the king ordered that all Gypsies who did not find a trade or profession to support themselves and start leading orderly lives (vida civil) would be deported to Angola.Footnote 112 The position of Gypsies in Brazil was shaped by their treatment not only in Portugal, but also by the demands and statuses of African colonies and in Spain, where Gypsies crossed the border from Portugal, whether in order to escape persecutions or to improve their situation. The dynamics that can be analysed in terms of modernization and the development of police tactics in one locale are driven by the demands of colonizing efforts in another.

Secondly, and relatedly, the Bahian case invites us to explore Gypsy treatment in the broader context of colonial and post-colonial formations. Recall Patroni's comments at the beginning of this article. These might be read as being made by a post-independence regional politician interested in improving the “Brazilian nation”. In other words, the nineteenth-century projects of policing and hygienization might be interpreted as reflecting nation-building efforts by modernizing elites in the wake of state-building. But this modernization thesis overestimates the post-colonial rupture and the discontinuity between imperial and nation-state projects. It also resonates too much with the view of history of the “victors”.Footnote 113 One way to denaturalize this tendency is to take a long view and to see the efforts of post-independence elites as an example of “internal colonization”. For ethnic minorities including Gypsies, who in Patroni's words were yet to be “colonized”, the end of Brazil's colonial status did not mean the end of colonial relations, although now domestic colonization was carried out under the cover of nation-building and new forms of racial science. In other words, the continued, but transformed, marginalization of Gypsies occurred in a context in which elites attempted to secure their position through evoking and enforcing racial and class inequalities through, among other things, the purported difference of Gypsies.

Between the sixteenth and twentieth century, the powerless in society were marshalled into serving European empires, and Gypsies were not excluded. In Portugal, Ciganos were among those who manned galleys and garrisons, or who broke paths into the hinterland of Bahia, or Maranhão, alongside enslaved Indians and before the labour was provided primarily by enslaved Africans brought into the Americas. And this is my final Bahian point: the official treatment of Gypsies cannot simply be seen as the creation of ethnic difference and its management. Rather, it should be placed within broader processes of racialization. If the main parameters of colonialism were set by the need to control labour and land, the logic behind the recurrent targeting of Gypsies at various levels of power becomes more comprehensible. As we have seen, concerns with Gypsies arose in moments when authorities felt confronted with unwanted social problems, particularly when the perceived mobility and attitude towards work of the povo was deemed problematic by authorities. Moreover, it suggests that stereotypes about Gypsies should be placed in the context of colonial and post-colonial race relations. During different periods and in different regions, they were treated as the Portuguese “Old Christians” of Gypsy “habits” and “kind”, and thus distinguished from Jews, Indians, and Africans. At other times, such as during the peak of the African slave trade, “Gypsy” becomes ossified into a race considered distinct from other races.

More generally, the figure of the Gypsy embodied tensions in Bahia between the white elite and those they considered the povo, including free black and Indian peasants. As small-scale, mostly ambulant traders, Gypsies belonged to the masses of humble origins, but they maintained their distinction from others, and were seen as such. They were economically integrated, but stood somewhat apart from established social relations founded on conquest and enslavement – Moraes Mello went so far as to proclaim that Gypsies were “the weld that united the three pieces of the current Brazilian racial mixture (mestiçagem)”.Footnote 114 Such a position was amenable to transformations through the politicization of difference. The fact that the concrete content of representations changes, sometimes abruptly as in Patroni's narrative, reveals the long-term structuring of colonialism: “it concerns less its ‘real’ object than the position of the enunciator in a relationship of power in relation to the latter”.Footnote 115