INTRODUCTION

Whereas the vast majority of Maya ceramics are quotidian, unslipped, and plain, made to fulfill a wide range of practical functions, there is one category of ceramics that stands apart from the rest. This particular category is serving vessels, especially those manufactured for the royal court. These serving vessels are distinguished from other ceramics by their surface treatments alone, which are usually highly smoothed and burnished, as well as decorated with a wide array of dazzling colors, detailed patterns, and elaborate iconographic scenes and glyphic texts (e.g., Reents-Budet Reference Reents-Budet1994).

By focusing on these highly decorated ceramics, we are able at times to appraise their motifs, iconography, and glyphs, which together enable us to determine where these ceramics were originally produced and for whom they were intended. Based on present evidence, these ceramics were circulated in a relatively restricted manner, making them an effective proxy to explore the relations and interactions between distinct courts in the Classic period. Royal courts of the ancient Maya were nodes of exchange, where prestigious goods were appraised and traded, but especially polychrome ceramics to tie and strengthen political, social, and other types of relations (Bishop Reference Bishop and van Zelst2003; Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart, Taube and Kerr1992; Reents-Budet Reference Reents-Budet1994; Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine2016). What we explore here are illustrative examples of such relations, which the secondary Maya site of Nakum maintained with different neighboring centers and regions of the northern Peten. As we will show, the ceramic assemblage of Nakum contains vessels whose style, glyphic texts, or chemical composition reveal nonlocal origins and affiliations. As we will try to demonstrate, however, such ceramics may not indicate foreign presence of people but rather the existence of complex interactions between different Maya elites. Many “foreign” ceramics found at Nakum seem to have been bequeathed, inherited, or traded by upper echelons of Maya society to foster alliances of different character. Such valuable objects in most cases were placed to elite burials or caches or used in ritual activities during which they were broken and subsequently scattered in the architectural core of the most distinguished buildings—funerary pyramids and other ceremonial structures.

Our major focus in this paper are the polychromatic and highly decorated ceramics found at Nakum over the course of the last decade of research by the Nakum Archaeological Project of the Jagiellonian University. Iconography backed in many cases by petrographic and physicochemical analyses of Late Classic-period Nakum ceramics indicate that this site had very close cultural and possibly also political connections with various neighboring centers, but especially with two principal powers of this region: Naranjo and Tikal.

Our reconstructions are based on both stylistic and archaeometric (petrography and instrumental neutron activation [INAA]) analyses of selected ceramic fragments. Whereas petrographic studies serve to study mineralogical components of ceramic paste and its major temper, INAA enables us to reconstruct chemical composition of ceramic clay that have a direct bearing on the origins of the specimens in question. The latter method has shown a great potential in reconstruction of cultural and political contacts as well long-distance trade of goods between different regions of Mesoamerica (Bishop Reference Bishop and van Zelst2003; Blackman and Bishop Reference Blackman and Bishop2007; Foias and Bishop Reference Foias, Bishop, Varela and Foias2005; Reents-Budet et al. Reference Reents-Budet, Bell, Traxler, Bishop, Bell, Canuto and Sharer2004). The crucial problem, however, remains the comparative data for the analyzed samples. The Nakum samples presented here were compared against the more than 45,000 sherds in a database of Maya pottery thus far analyzed by neutron activation at Smithsonian Institution of Washington as part of the Maya Ceramics Project. The major aim of this project, coordinated by Bishop and Reents-Budet, is to sample and document the chemical composition of pre-Columbian Maya ceramics from many different lowland sites as well as from private and public collections. During the INAA, a final one-to-one search was carried out in which each of the Nakum samples was compared against the substantial sherd database of Maya pottery at Smithsonian Institution of Washington. Using a commonly employed Euclidean distance calculation based on the elemental concentrations with low analytical error, few samples were found that “matched” other pottery at Nakum (previously sampled by Fialko) or at other neighboring Maya sites. This enabled us to seek compositional similarities with various neighboring sites and regions, as well as with other local Nakum ceramics that had been sampled as part of earlier INAA studies.

Although the collection of ceramics presented in this paper is modest and encompasses six samples from vessels or ceramic fragments that were subject to archaeometrical analyses, we selected for these analyses ceramics that clearly stand out of the whole ceramic assemblage of Nakum due to their stylistic attributes and hieroglyphic texts. Based on both INAA and stylistic data, it seems very plausible that the political fortunes of Nakum were initially closely tied to Naranjo, whereas, during the latter part of the Late Classic, after the victory of Tikal over Calakmul in 695, Nakum seems to shift to a more Tikal-centric focus. This is followed, towards the end of the Classic era, with the short-lived independence of Nakum in the face of the collapse of major powers of this region.

NAKUM: SITE SETTING AND CHRONOLOGY

Nakum is a secondary Maya center located in northeastern Guatemala, in the area of the Yaxha-Nakum-Naranjo National Park. The park encompasses 371 km2 and three major cities of Naranjo, Nakum, and Yaxha, with many other smaller centers also situated in this area (Figure 1). Recently, Nakum has been the subject of archaeological investigations carried out by a team of Polish and Guatemalan scholars between 2006 and 2017. This, as well as previous research conducted by the Instituto de Antropología e Historia, reveals that Nakum was first settled during the Middle Preclassic period (1000/900–300 b.c.), but experienced its apogee in the Classic era, especially during the Late and Terminal Classic (a.d. 550/600–900/950). One of the most interesting developments in the history of this site is its anomalous growth towards the end of the Classic period—the ninth and the beginning of the tenth centuries—a time that is otherwise characterized by a profound crisis and collapse of most lowland Maya centers. Nonetheless, during this time, Nakum witnessed major architectural programs and its lords commissioned the largest number of carved monuments documented to date at the site (Helmke et al. Reference Helmke, Martin, Źrałka, Zych, Koszkul, Rusek, Velásquez, Arroyo, Méndez and Ajú2018; Źrałka and Hermes Reference Źrałka and Hermes2012).

Figure 1. Map of northern Peten and surrounding areas with location of Yaxha-Nakum-Naranjo National Park, and most dominant sites of the region. Map by Bojkowska.

Nakum consists of two major parts denominated the North and South Sectors that are connected by an elevated causeway (Périgny Causeway), which is 250 m long and 25 m wide. These two major sectors are formed by monumental architectural constructions featuring pyramidal temples, palaces, and buildings serving many other functions, most of them arranged around plazas. The largest and most impressive part of the site is the Southern Sector, where we see concentration of the tallest buildings; most pyramids are located here. Additionally the enormous Acropolis, consisting of a large platform topped by more than 60 structures (most of them residential and administrative constructions) arranged around courtyards, is also located here. It has been argued (Źrałka and Hermes Reference Źrałka and Hermes2012:168–169) that the seat of a royal dynasty during the Terminal Classic period (a.d. 800–900/950) was located in the hearth of the Acropolis (in the area of complex denominated Central Acropolis).

Since the subject of borders is one of the major themes of this Special Section, it must be stressed that Nakum was located in a very dynamic geopolitical zone. It is situated equidistantly between Tikal and Naranjo (approximately 22 kilometers from Tikal and 16 kilometers from Naranjo), two central polities that became staunch antagonists during the Classic period (Martin and Grube Reference Grube and Wurster2000). Naranjo, as a key vassal of the Snake or Kanul dynasty, became a natural enemy of Tikal under the long reign of the Naranjo king that is referred to in the epigraphic literature as Aj Wosal (regnal years: a.d. 546–ca. 615). Nakum was located in a region that could be described as a buffer zone, where the political interests of these two powerful kingdoms conflicted and clashed. As for now, no major fortifications marking the frontiers of these kingdoms have been documented in this area. We should remember, however, that although physical borders are known in the Maya area in such centers and regions as Tikal, Becan, the Pasión Region, and the Usumacinta (Demarest et al. Reference Demarest, O'Mansky, Wolley, Van Tuerenhout, Inomata, Palka and Escobedo1997; Puleston and Callender Reference Puleston and Callender1967; Scherer and Golden Reference Scherer and Golden2009; Webster et al. Reference Webster, Murtha, Straight, Silverstein, Martinez, Terry and Burnett2007; see also Canuto et al. [Reference Canuto, Estrada-Belli, Garrison, Houston, Acuña, Kováč, Marken, Nondédéo, Auld-Thomas, Castanet, Chatelain, Chiriboga, Drápela, Lieskovský, Tokovinine, Velasquez, Fernández-Díaz and Shrestha2018] for defensive systems revealed by the PACUNAM LiDAR Initiative in northern Guatemala), in general Mesoamerica is characterized by the existence of what we may call “open borders.” These are unmarked borders with open borderlines that usually align to natural features such as rivers, mountains, lakes or forests (Helmke et al. Reference Helmke, Ebert, Awe and Hoggarth2019a; Trigger Reference Trigger2003). In this context, we should mention that the vast bajo La Justa could have served precisely as such a natural border, disabling ingress of warring parties as well as other groups.

The bajo La Justa is a seasonal swamp located between Nakum and Yaxha, covering the area of 150 km2. The existence of architecture was confirmed within elevated parts of the bajo during previous research carried out by Culbert (Culbert et al. Reference Culbert, Fialko, McKee, Grazioso, Kunen, Paez, Laporte and Escobedo1997), Fialko (Reference Fialko2005), and other scholars (Kunen et al. Reference Kunen, Culbert, Fialko, McKee and Grazioso2000). Contrarily, there were no traces of settlements documented in the low-lying areas, as they were exposed to repeated flooding in the rainy season. During these periods, bajos become marshy thickets that are greatly difficult to cross (Kunen et al. Reference Kunen, Culbert, Fialko, McKee and Grazioso2000:17, 21). Likewise, various scholars (Carr and Hazard Reference Carr and Hazard1961:9; Haviland Reference Haviland and Ashmore1981:89; Puleston and Callender Reference Puleston and Callender1967:41–47) have suggested that the bajos located close to Tikal formed natural boundary of this center. In addition, artificial earthworks were constructed to the north, south and west of Tikal between the bajos, presumably to demarcate the city from each side (Garrison et al. Reference Garrison, Houston and Firpi2019; Haviland Reference Haviland and Ashmore1981:89; Webster et al. Reference Webster, Murtha, Straight, Silverstein, Martinez, Terry and Burnett2007). Bajo La Justa, could also be considered as a natural boundary between Naranjo and Tikal, and perhaps is the reason Nakum was located in that area as a border city.

EARLY CLASSIC AND TEOTIHUACAN TIES

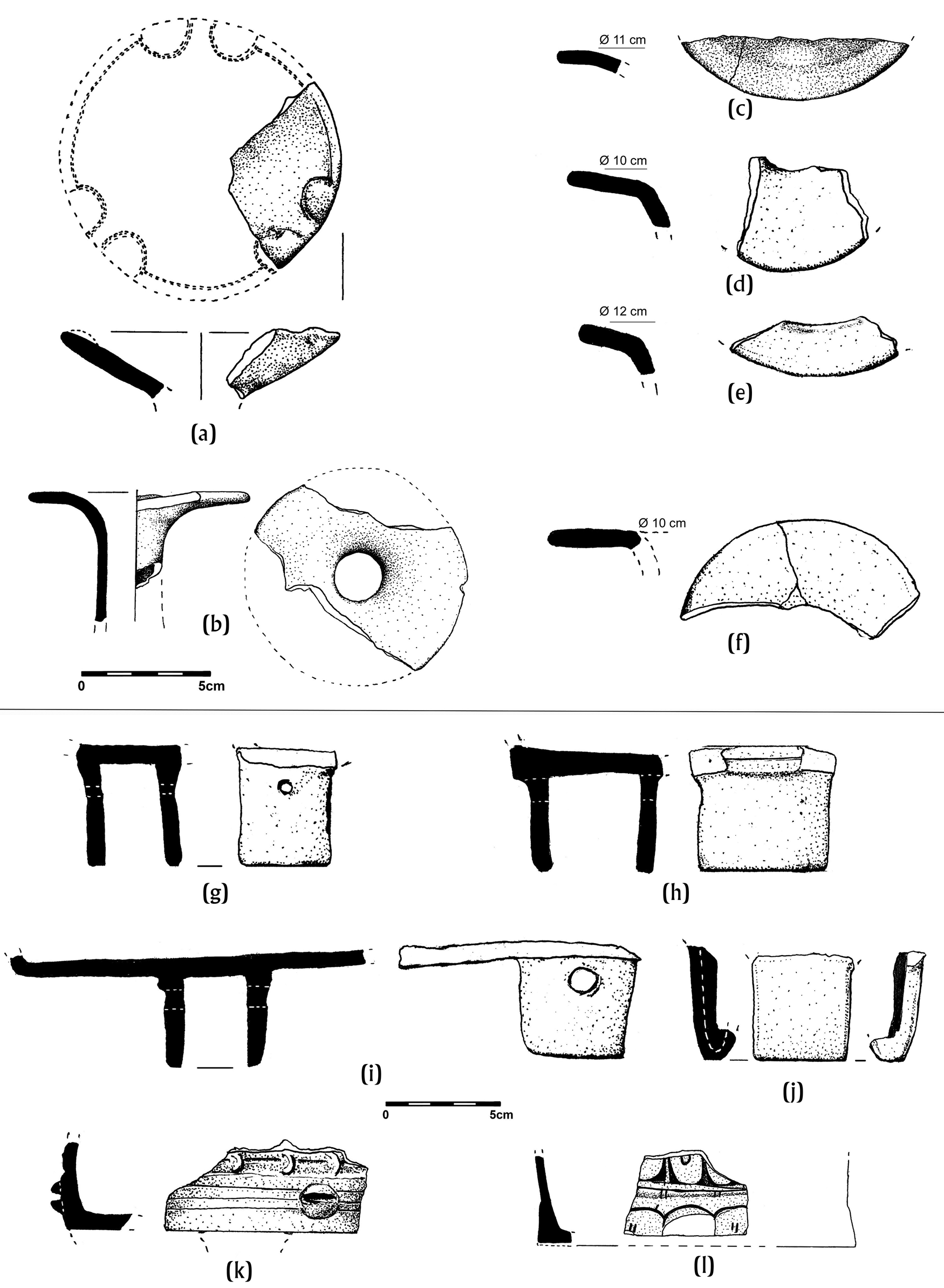

Before we move to the major topic of our paper, that of Late and Terminal Classic ceramics and their exchange, it is worth mentioning the subject of cultural and political affiliations of Nakum during the first part of the Classic period. The famous entrada event that took place in a.d. 378 and was followed by a series of incursions and conquests in the Guatemalan Peten (Stuart Reference Stuart, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000) undoubtedly had a serious impact on Nakum and neighboring Yaxha. Although we do not have direct epigraphic evidence to support this claim, one carved monument at Yaxha (Stela 11) depicts a personage in Teotihuacan attire—most likely Sihyaj K'ahk’ himself or one of his lieutenants (Grube Reference Grube and Wurster2000:255). This incursion, however, seems to be a very brief one, as we find almost no archaeological evidence of Teotihuacan contacts at Yaxha in terms of ceramics and architecture. That said, Yaxha has very sparse Early Classic architectural activity. Nakum, however, has an interesting complex consisting of four connected talud-tablero platforms enclosing a large plaza (Patio 1; Koszkul et al. Reference Koszkul, Hermes and Calderón2006). In terms of its architectural layout, the complex finds its closest counterparts in Teotihuacan itself. Recent excavations of one of these platforms (Structure G Sub-3 enclosing Patio 1 from the south) produced in its core numerous artefacts of Teotihuacan affiliation, including fragments of floreros, tripod cylinder vases with slab feet, and green obsidian (projectile points, blades, and other artefacts; Figure 2). These artefacts belong to the so-called Nayes ceramic complex, which is the local equivalent of Tzakol Horizon, and specifically of its latter facets (Tzakol 2–3; Hermes Reference Hermes2019). Besides, recent analysis of the oxygen isotopes of a sub-adult tooth recovered from the fill of the talud-tablero platform G Sub-3 shows nonlocal δ18O value, which are in the range of central Mexico. Since the enamel of the tooth forms in utero, the nonlocal value of the sample reflects migration of this individual's mother to the Peten, most probably from central Mexico though other areas such as Guatemalan Highlands, southwestern Mexico, or the Pacific Coast cannot be excluded on the basis of very similar low δ18O values (Rand et al. Reference Rand, Matute, Grimes, Freiwald and Źrałka2020). Several radiocarbon samples from the core of the latter construction produced dates that indicate the whole complex most probably postdates the entrada events. In our opinion, a Teotihuacan-related order might have been established in this region via Tikal. In the Triangle Park area, this would have included at least Yaxha and Nakum, the two centers that might have been under the political influence of Tikal both before, as well as after the entrada.

Figure 2. Examples of ceramic artefacts of Teotihuacan affiliation found at Nakum: (a–f) fragments of floreros and (g–l) tripod cylinder vases with slab feet. Drawings by Piotr Kołodziejczyk.

MIDDLE CLASSIC AND CONNECTIONS WITH NARANJO

Available archaeological data indicate that during the initial part of the Late Classic period, Nakum's political fortunes were tied to Naranjo, a powerful center located just 16 km southeast of Nakum. Such ties were most probably established during the reign of one of Naranjo's most famous and powerful lords, Aj Wosal (Martin and Grube Reference Grube and Wurster2000:71–72). Several vessel fragments found at Nakum show clear stylistic links to the ceramics produced under the patronage of this Naranjo king.

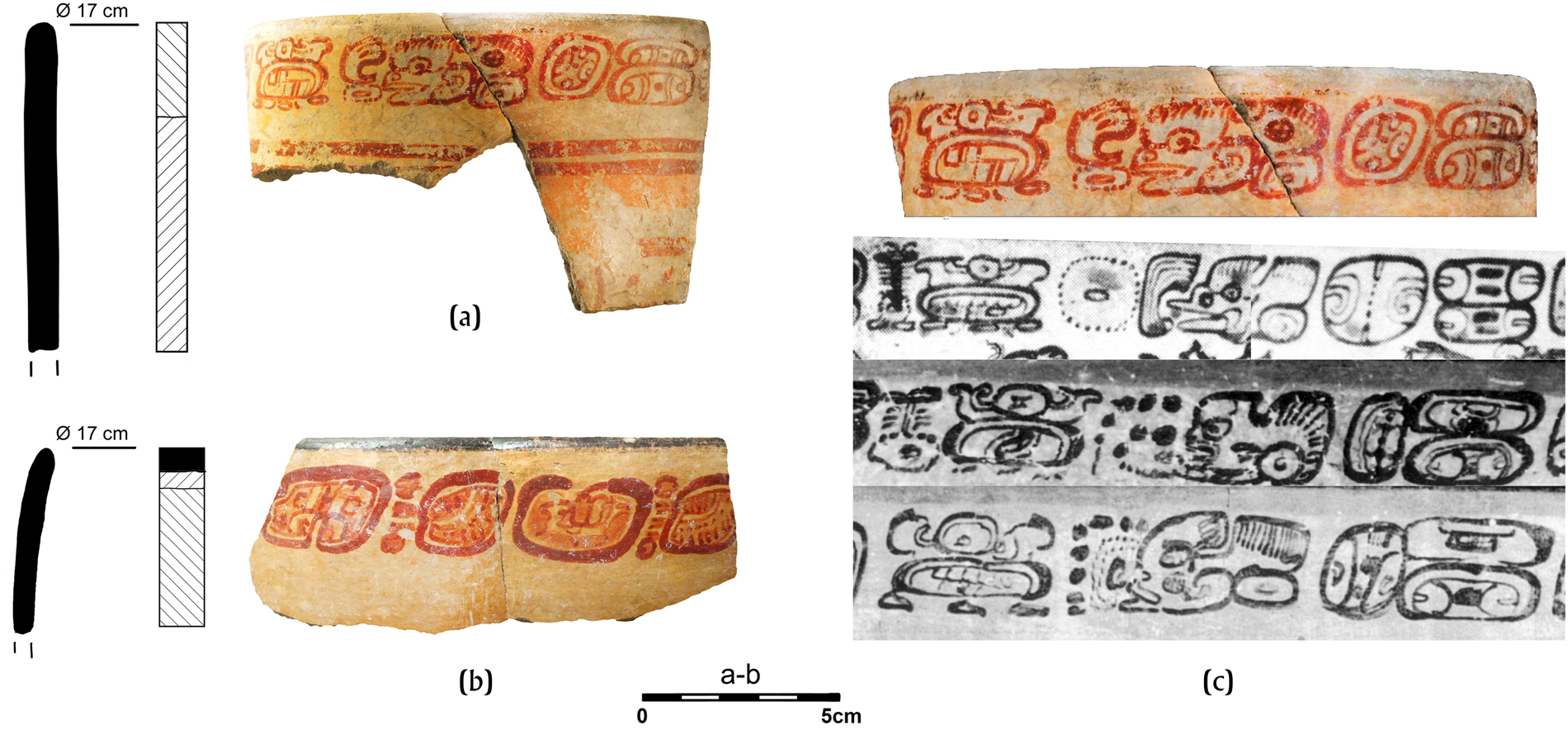

The first is the rim of a cylindrical vessel found in the core of Structure 14 that borders Patio 1 on the southeast (Figure 3a, Table 1). This structure played a prominent role in the religious and social life of Nakum, serving as one of the major temples, which for at least some part of its existence served as a provisional burial place where esteemed individuals might have been located before the final burial took place (Źrałka and Koszkul Reference Źrałka and Koszkul2015). Many beautiful vessels, including the examples described in this paper, were deposited in its core in what must have been ceremonial activity related to the rebuilding and expansion of this construction. The preserved fragment's exterior is decorated with red-painted glyphs along the rim. The text refers to the content of the vase, and the ownership. The contents, as preserved, is written yutal ka[kaw], or “[for] fruity kakaw,” followed by CHAK-ch'o-ko, for chak ch'ok, or “great youth.”

Figure 3. (a and b) Two vessel fragments found within the core of Structure 14 and exhibiting paleographic affiliations to the ceramic workshops patronized by Aj Wosal, the great king of Naranjo. (a) Palmar Orange Polychrome. (b) Saxche Orange Polychrome. Photographs by Robert Słaboński. (c) Examples of very similar ceramic vessels (Kerr Nos. K1558, K2704, and K5042) produced for Aj Wosal. Details of photographs by Justin Kerr.

Table 1. List of ceramic fragments mentioned in the text that were subject of instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA) and petrographic analyses.

Although the name of the owner is not preserved, there are a series of paleographic features that suggest links between this specimen and those of Naranjo. In fact, the glyphs of these vessels can be compared to the analogous contents and titular sections of the vessels produced for Naranjo's Aj Wosal. Close comparisons can be drawn with at least three of the vessels of Aj Wosal including K1558, K2704, and K5042 (Figure 3c; Kerr Reference Kerr2019). In each of these cases, the same type of dedicatory inscription is visible. These glyphs are distinctive enough to imply that, while these vessels might not have been produced by the same scribe, they certainly belonged to the same scribal milieu. That being said, recent INAA of this specimen shows that it has the strongest links with local Nakum ceramics. This may indicate that it was manufactured at Nakum or at a local workshop either patronized by the Naranjo court or its artisans, or alternatively is a local production emulating a Naranjo style. The form of the vessel is more vase-like and thereby suggests that it dates either to the end, or shortly after, the reign of Aj Wosal, a typological attribute that may speak in favor of local emulation.

A second fragment equally suggests links to Aj Wosal's ceramic workshop based on its paleography. The fragment in question comes from a Saxche Orange Polychrome type bowl and it features a fragment of text of the PSS (Primary Standard Sequence) series (Figure 3b). The glyphs are very similar to the glyphic texts from the vessels such as K4958, K2704, K4562, or K5042, all of which belong to Aj Wosal's ceramic workshops and mention his name. The latter fragment has been also found in the core of the aforementioned Structure 14.

One more example that betrays links with Naranjo under the reign of Aj Wosal is another ceramic bowl of the Saxche Orange Polychrome type (vessel PANFC 025; Figures 4a–4d), which is very similar to the fragment just described. In this case, however, it is the iconography that is more revealing. The long and slender linear elements together may form the stylized beak of a hummingbird. The main diagnostic element of a hummingbird in Maya iconography is the flower that adorns its elongated beak, or bill, as though the flower and bird are interdependent in generating meaning in Maya thought and representational conventions. In this context, we should mention a vessel, which is now in the collections of the Museo del Vidrio in the Hotel Santo Domingo in La Antigua, Guatemala (Luin et al. Reference Luin, Beliaev, Galeev, Vepretskiy, Arroyo, Méndez and Ajú2018:879, Figure 3). The iconography on this bowl is dominated by a kneeling male figure who braces a large ceremonial bar (Figure 4e). The text along the rim confirms that this was once owned by none other than Aj Wosal. The connection to Naranjo, as expressed on this vase, is more profound, since one of the major tutelary deities of the dynasty was a hummingbird deity, or better said, the hummingbird aspect of a feline entity in anthropomorphic form (Helmke et al. Reference Helmke, Hammond, Guderjan, Greaves and Hanratty2019b:20–21, 23, 25). Recent excavations at Naranjo, conducted by Vilma Fialko, have revealed a palace building named Aurora, located within the so-called Central Acropolis complex that is embellished by hummingbirds and depictions of this hummingbird deity in relation to a sacred florid mountain. The latter structure was part of a royal palace complex of Aj Wosal, and its decoration further confirms the centrality of this supernatural being in local myths and historical narratives (Tokovinine and Fialko Reference Tokovinine, Fialko, Arroyo, Méndez and Ajú2019).

Figure 4. (a–d) Ceramic bowl decorated with pseudoglyphs and stylized representation of a hummingbird beak. Vessel PANFC 025 of Saxche Orange Polychrome type. Photograph by Robert Słaboński, drawings by Katarzyna Radnicka. Other representations of hummingbird deity: (e) the vessel from the collection of Museo del Vidrio in the Hotel Santo Domingo in Antigua Guatemala (drawing courtesy of Filipp Galeev) and (f) from a bowl excavated at Paxte (after Hermes Reference Hermes and Wurster2000:Figure 141:3).

Another vessel fragment found on island of Paxte on lake Yaxha, just 11 km to the south of Nakum, represents a very similar anthropomorphic figure; a long projection emanates from his nose, which likewise appears to perforate a florid element (Figure 4f; Hermes Reference Hermes and Wurster2000:Figure 141:3).

Together, these vessels are essentially identical to the vase that Estrada-Belli (Reference Estrada-Belli and Estrada-Belli2018) recently uncovered in one of the burials located in Holmul Structure D. The latter vessel depicts an individual in a hummingbird mask, and its text equally identifies its owner as Aj Wosal, indicating it was bestowed to a local Holmul king as a special gift (Estrada-Belli Reference Estrada-Belli and Estrada-Belli2018:10–11).

Although highly stylized, the schematic beak of the hummingbird, penetrating the characteristic flower on the Nakum vessel, together may serve to cue the tutelary deity of Naranjo, which along with the other stylistic features of the bowl, once again point to a period, or at least an episode, of close contact with Naranjo, during the late sixth and early seventh century.

All the above-described vessels reveal close connections between Nakum and Naranjo at this relatively early date, with Naranjo presumably in dominant position and Nakum in subservience. This provides the impression of a strong and regionally dominant Naranjo during the reign of Aj Wosal, and all the evidence present certainly points to this as the prevailing picture. This situation is similar to what we observe in many other contemporaneous Maya sites of the eastern Peten (e.g., Holmul) and western Belize which were under a strong influence and political control of Naranjo (Estrada-Belli Reference Estrada-Belli and Estrada-Belli2018; Estrada-Belli and Tokovinine Reference Estrada-Belli and Tokovinine2016; Helmke and Awe Reference Helmke and Awe2008:79–84).

LATE CLASSIC RELATIONS WITH TIKAL

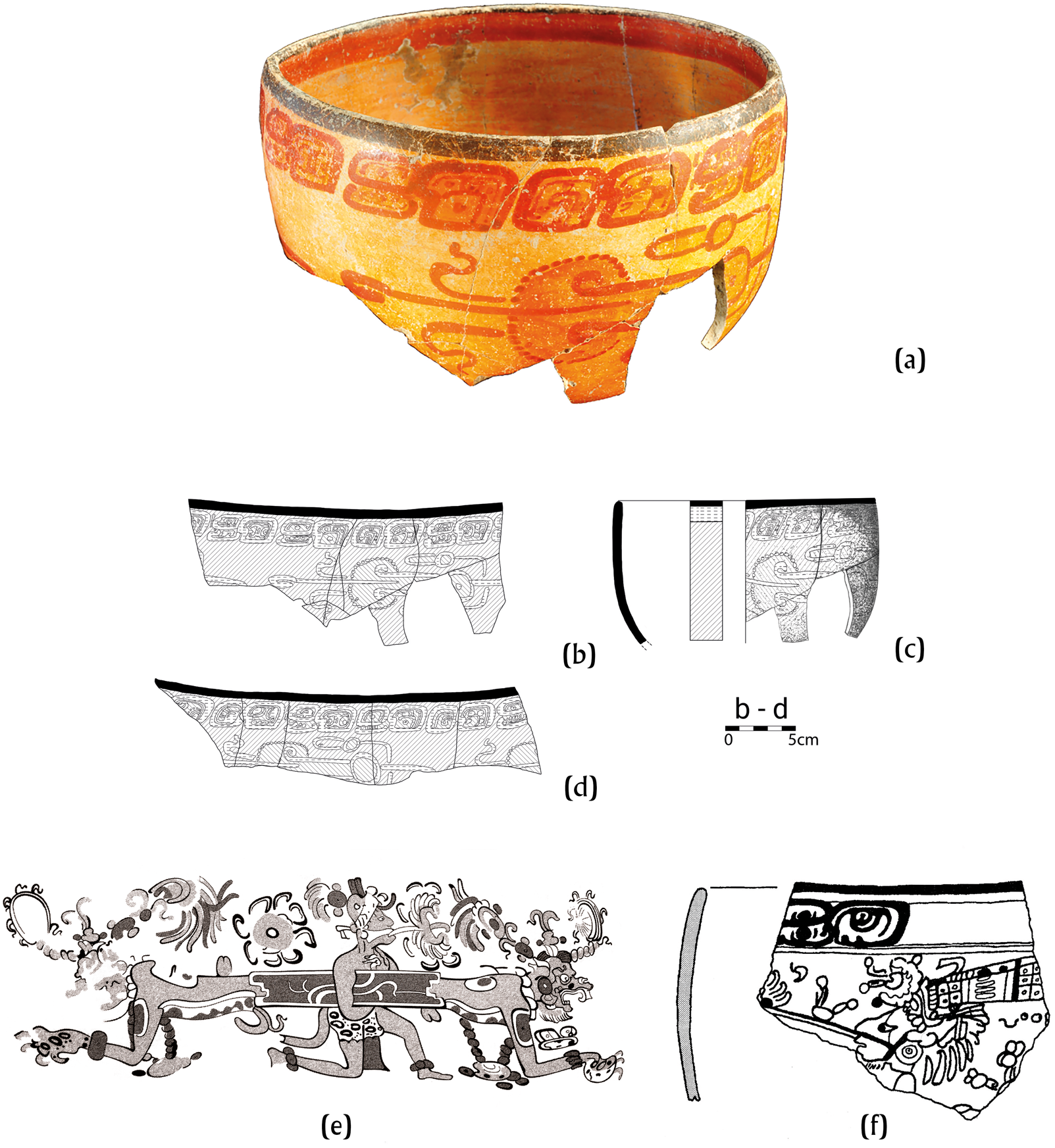

One of the hallmarks of the eastern central lowlands are the finely painted ceramic vessels bearing the so-called Holmul Dancer scenes, named after the type specimen encountered at that site in 1911. The imagery on these vessels is typically painted in dark red outlines, with diluted orange wash applied sparingly to define figurative elements in the foreground. These stand out on the neat cream backgrounds that define the ceramics of this type. Primary emphasis of the Holmul Dancer scenes is placed on the Maize god, represented dancing in majesty, bearing intricate regalia, and often assisted by a dwarf. These scenes are interpreted as representing a pivotal moment in the mythic narrative of the Maize god: his resurrection from the Underworld (Helmke Reference Helmke and Helmke2019; Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart, Taube and Kerr1992; Reents-Budet Reference Reents-Budet and Fields1991).

The themes of the Holmul Dancer vessels were of great significance to the sites of the eastern central lowlands, with Naranjo, Holmul, Xultun, and Río Azul distinguishing themselves as key production centers of this type of ceramic (Helmke Reference Helmke and Helmke2019:125–139; Reents-Budet Reference Reents-Budet1994:179–185, 294–305). The rim texts of these vessels include the standard dedicatory formula and prominently name their original owners. For Naranjo, these were owned gby the seventh century king K'ahk’ Tiliiw Chan Chaahk (regnal years: a.d. 693–728+) who was a patron of the production of many such vessels (Martin and Grube Reference Grube and Wurster2000:74–77).

The discovery at Nakum of a rim sherd of the vessel of such style (Figure 5a) is not particularly surprising per se, given the proximity to Naranjo, one of the major production centers of ceramics of this group. What is remarkable, however, is that the name of the owner of that vase is preserved, and that it names a king of Tikal. The reference is made through the well-known royal emblem glyph of the kings of Tikal, written K'UH-MUT-AJAW for k'uh[ul] mut[u'l] ajaw, or “godly Mutu'l king,” a title built on the toponym of the ancient metropolis.

Figure 5. Ceramics of the Holmul Dancer style or of similar stylistic affiliation documented at Nakum. (a) Ceramic rim with text mentioning Tikal Emblem Glyph (Naranjal Red-on-Cream). (b) Nakum vessel PANC 009 (Zacatal Cream Polychrome?). (c) Vessel PANFC 035 found in Nakum Burial 11 (Naranjal Red-on-Cream). Photographs by Robert Słaboński and Źrałka, drawings by Bojkowska.

Since Tikal is not known as a production center of Holmul Dancer ceramics, we are inclined to conclude that this vessel was most probably produced at an established workshop, given the quality of the line work and ceramic generally, and crafted as a bespoke vase, made specifically to be given to a lord of Tikal as a sign of thanks and gratitude. It is quite possible that the fragment in question comes from a vase made specifically for a king of Tikal in one of the royal workshops of Naranjo. This observation may be further supported by results of the INAA analysis, which show some connections with Naranjo region (or at least the greater Holmul region) in terms of the chemical composition of the paste but no links to Tikal or the greater Peten Lakes region. Petrographic analysis of this vessel shows that a volcanic ash-tempered ceramic paste was used (Figure 6a), which is common among the polychrome vessels that were produced during this time period.

Figure 6. Photomicrographs of the thin sections of three polychrome ceramic fragments from Nakum featuring different temper. (a) Sample 2 from vessel shown in Figure 5a. Ceramic paste was made of very angular volcanic ash with biotite, plagioclase, and quartz in the matrix and the ceramic body was covered with a thick layer of slip made of calcareous clay, followed by paint. (b) Sample 4 from vessel PANFC 031, shown in Figure 10a. Ceramic paste has volcanic ash temper with only a few other inclusions in the fabric presented. The paint was applied directly to the surface of the vessel, without any slip layer underneath. (c) Sample 5 from vessel PANFC 032, shown in Figure 8. Paste was made of a fabric that contains only calcite and the ceramic body of the vessel was covered with a thick layer of slip made of calcareous clay, followed by paint.

The question is how did this vase make its way to Nakum? According to one hypothesis, it might have been secondarily gifted by the Tikal king to one of the Nakum lords to cement ties between Tikal and its lesser neighbor to the east. These critical questions cannot be resolved at present based on the data available, yet this single sherd highlights a highly dynamic period of intrasite interactions and allegiances, which has not yet been fully appreciated.

As an analogy to our Nakum find, we can mention the so-called Cormorant Vase described by Reents-Budet (Reference Reents-Budet1994:300–301) in her famous book on painted Maya ceramics. Although the exact provenience of the Cormorant Vase is unknown, its chemical profile and style indicate that it was produced in Naranjo under the patronage of K'ahk’ Tiliiw Chan Chaahk. The PSS text of this vessel, however, ends with the name of the Ucanal king, “Itzamnaaj” Bahlam, as its owner. It seems then that the vessel might have been commissioned by the Naranjo king to be made for the ruler of Ucanal, possibly to cement political alliances between these two cities (Helmke et al. Reference Helmke, Polyukhovych, Reents-Budet and Bishop2017:19–21; Reents-Budet Reference Reents-Budet1994:300–305). The famous discovery of a Holmul Dancer vase (called Jauncy Vase) of K'ahk’ Tiliiw Chan Chaahk, deposited in a tomb of Buenavista del Cayo lord might also be recalled here (Taschek and Ball Reference Taschek, Ball and Kerr1992). The paste composition combined with paleographic features of the Jauncy Vase and the Cormorant Vase indicate that they both might have been manufactured at the same workshop attached to Naranjo court during the reign of K'ahk’ Tiliiw Chan Chaahk (Helmke et al. Reference Helmke, Polyukhovych, Reents-Budet and Bishop2017:11). The latter examples show how this famous Naranjo king was known from giving/gifting vessels, both ceramics that name him as owner, as well as those produced in his workshops but naming other lords with whom K'ahk’ Tiliiw Chan Chaahk wanted to keep special political and cultural relations. The Nakum fragment described above fits this model although available data (INAA backed by epigraphic and stylistic analysis as well as archaeological context of the find) indicate secondary gifting from Naranjo to Tikal and then to Nakum.

Another interesting vessel from Nakum that shows links with the Holmul-style pottery is a cylindrical vase, 13.8 cm high, of the Naranjal Red-on-Cream type (PANFC 035; Figure 5c). It was recently found in a grave (Burial 11), placed within a notable residential group situated on the periphery of the site (Structure 229 of Patio 52) but very close to the epicenter, and most probably inhabited by a leading noble family. It is very similar to the Holmul-style pottery, especially to the vessels of Cabrito Cream Polychrome from Buenavista del Cayo or Baking Pot, which were two prominent production centers of this ceramic style. The Nakum example, similar to its Belize counterparts, is characterized by lesser quality painting and lack of legible PSS texts. It should be also stressed that fragments of a similar ceramic type have also been discovered in several other locations of epicentral Nakum. In addition, one completely preserved vessel (PANC 009) is very similar in its form and design to Holmul-style pottery, which features a star motif painted in red outlines and an orange interior on a cream background (Figure 5b).

SOME FURTHER COROLLARIES: TO THE WEST AND EAST

That Nakum maintained close relations with Tikal is made evident by other ceramic finds made at Nakum. For instance, the well-known Tikal Dancer plates, typical for the Tikal region, are in essence just local adaptations, equally representing the Maize god dancing out of the Underworld at his resurrection (Boot Reference Boot2003; Reents-Budet Reference Reents-Budet1994:197–198). One such Tikal Dancer plate (vessel PANC 002; Figure 7) was found in a particularly well-furnished royal tomb (Burial 1), excavated within Structure 15 in the Acropolis of Nakum, and dated to around a.d. 700 (Hermes Reference Hermes2019:432). The individual buried in that tomb was evidently a distinguished figure at Nakum, given the value of the materials found, including a rich array of jade jewels, three vessels, spindle whorls, and other artefacts. Among the many items of personal adornment was a large, carved, and inscribed early jadeite pectoral, clearly an heirloom, dating to the Protoclassic or beginning of the Classic period (Źrałka et al. Reference Źrałka, Koszkul, Martin and Hermes2011).

Figure 7. Drawings and photographs of vessel PANC 002 found in Nakum Burial 1 and belonging to the Tikal Dancer style (Saxche Orange Polychrome type). Drawings by Katarzyna Radnicka and photographs by Źrałka.

Related to the above is another Saxche Orange Polychrome (PANFC 032) plate, of which only two fragments have survived (Figure 8). The plate was found broken into pieces in the core of Structure 14. Based on the size of these fragments, the plate was likely 41 cm in diameter. The INAA results designate the plate for the greater Tikal region, both the site and its periphery. The preserved elements of the iconography indicate that it once represented an individual in a dancing position. Consequently, based on the INAA results and its iconography, this vessel was most likely another example of a Tikal Dancer plate produced in the greater Tikal region. What merits special attention here are the glyphs decorating the rim of the plate. Apart from two regnal names, we find a fragmentarily preserved glyph that consists of a comb sign preceding a main sign representing a male profile, which may serve as part of a title. At present, the precise identity of this glyph is unclear, but the regnal names can be partially made out as K'ahk’ Pitay and Mo’ Yopat, undoubtedly naming the original owner of the plate. Based on present evidence we cannot tie in this name to any other known regnal name, at either Nakum or abroad, but we are inclined to see this as foreign reference and thereby an import to the site.

Figure 8. Nakum vessel PANFC 032 revealing stylistic and chemical similarities to the Tikal Dancer plates (Saxche Orange Polychrome type). Photograph by Robert Słaboński.

It is during the late seventh century that we see a profusion of another group of Zacatal Cream-polychrome ceramics, decorated with the “Dress Shirt” design, so named because of its apparent similarity to a freshly-laundered dress shirt. Yet, a more in-depth analysis of this motif reveals that it is in fact the distinctive feathers of the quasi-supernatural muwaan bird. The rich ceramic assemblage found in the tomb of the renowned Tikal king, Jasaw Chan K'awiil I, beneath the archetypal Temple I, includes several Zacatel vessels, decorated in precisely this fashion (Culbert Reference Culbert1993:Figures 91–96), and may point to Jasaw Chan K'awiil as the originator of this motif and ceramic type, which also became very popular during the reign of his successors. Ceramics of this type were found in an impressive assemblage within a chultun excavated by Tozzer (Reference Tozzer1913:188–190) at the beginning of twentieth century and at several other locations at Nakum (Figure 9). One of the vessels was fashioned in a series of stacked tiers, as seen in Figure 9b. The presence of such ceramics at Nakum, thereby, further highlights close relations with Tikal during the reign of this late seventh century king.

Figure 9. Vessels decorated with the “Dress Shirt” design found at Nakum, Zacatal Cream Polychrome type (after Tozzer Reference Tozzer1913:Figures 85–86).

RELATIONS TO THE CENTRAL PETEN

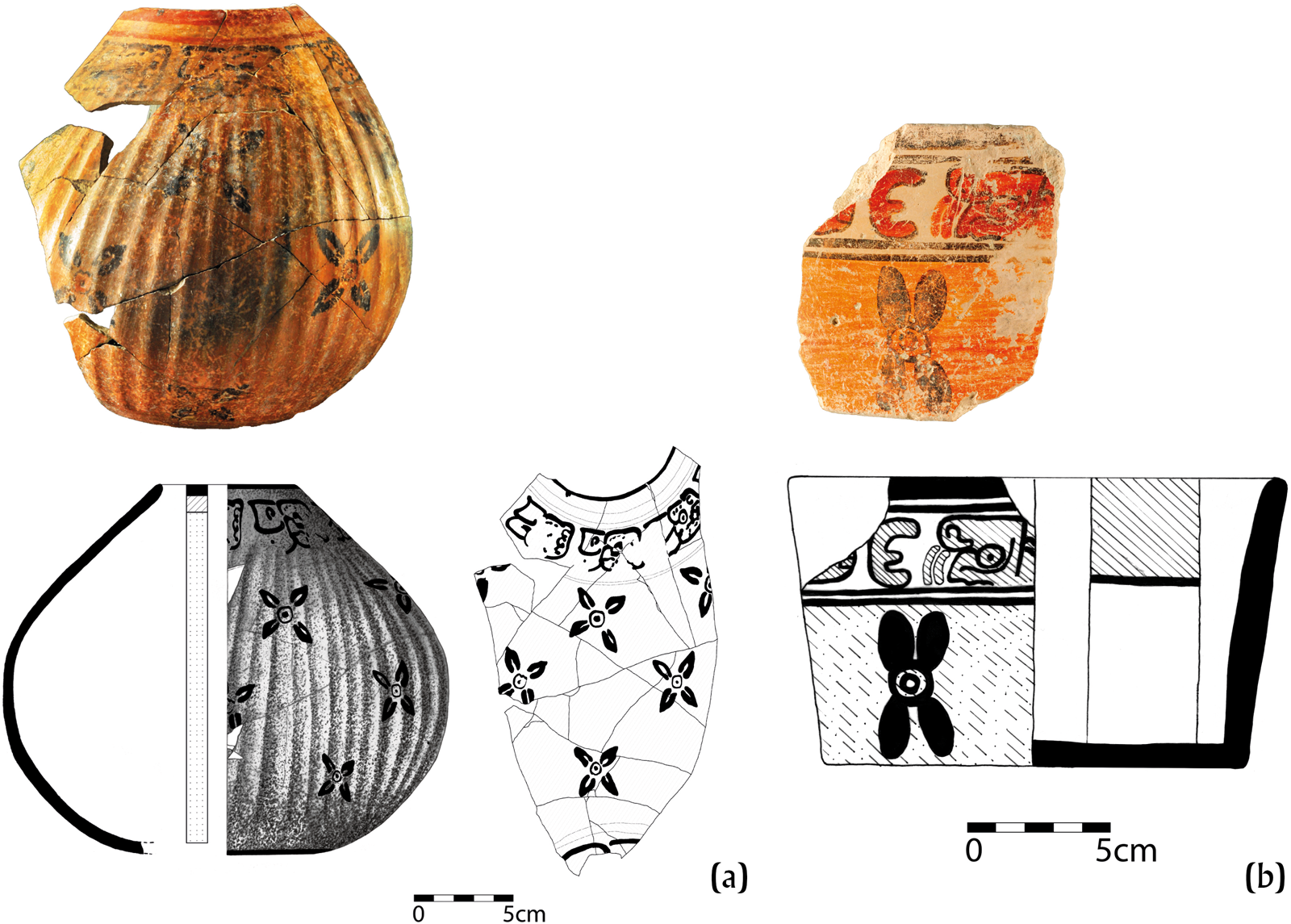

Other ceramics found at Nakum also reveal the relations with neighboring sites and with the central Peten as a whole during Tepeu 2 horizon or eighth century a.d. This connection is made obvious by the Palmar Orange Polychrome vessels that are adorned by black-painted, stylized, four-petalled flowers. Although the decorative mode may be consistent, the vessels forms vary widely, and include bowls, cylindrical vases, vases with vertical fluting, and pyriform vases, with or without fluting. Ceramics decorated by this motif have been identified at a number of sites in the area, including Uaxactun, Topoxte, Naranjo (K4379), Tikal, and Xultun (K4388), to name just a few.

The two most salient specimens found at Nakum both bear pseudoglyphic texts. One was part of a small bowl with straight and lightly everted sides, with an orange background for the figurative register below, and a cream ground for the upper glyphic register (Figure 10b; vessel PANFC 033). This specimen may be local, or may have been produced at nearby Yaxha, as indicated by the INAA analysis. The other is an orange-slipped globular jar with a constricted orifice and extensive fluting on the exterior (Figure 10a; vessel PANFC 031). It was found broken into several pieces on the floor of a pyramidal temple (Structure X), and most probably associated with veneration rituals dedicated to the deceased king buried in a tomb constructed below this temple room. This specimen, as indicated by INAA, may have been produced at Naranjo, further testifying to ties between the two sites. Again, petrographic analysis of this sample shows that a volcanic ash-tempered ceramic paste was used (Figure 6b), similar to the one that was used to make the vessel of Holmul Dancer style shown in Figure 5a. The decorations on each of these two specimens are applied in black paint, with red serving to highlight features as well as provide delineations.

Figure 10. Two Nakum vessels decorated with pseudoglyphs and stylized motif of four-petalled flowers. (a) Vessel PANFC 031 (Granja Central Compuesto). (b) Vessel PANFC 033 (Palmar Orange Polychrome type). Photographs by Robert Słaboński and drawings by Bojkowska.

THE TERMINAL CLASSIC PERIOD AND MOLDED-CARVED CERAMICS AT NAKUM

The Terminal Classic period (ca. a.d. 800–900/950) opens up a new chapter in the history of Nakum. The collapse of Classic Maya civilization in the lowlands brings up marked sociopolitical changes, which must have affected political alliances and geopolitical structure, including the existing borders and spheres of influence in the southern Maya lowlands. Large powers, such as Tikal and Naranjo, suffered from demise and power fragmentation. Some smaller polities, however, experienced short-term independence and cultural growth. Nakum elites realized prominent architectural programs and dedicated carved monuments at this juncture. Most of the six stelae documented at Nakum were commissioned during the ninth century a.d. (Helmke et al. Reference Helmke, Martin, Źrałka, Zych, Koszkul, Rusek, Velásquez, Arroyo, Méndez and Ajú2018; Źrałka et al. Reference Źrałka, Helmke, Martin, Koszkul and Velásquez2018). For the first time, we also have evidence of the use at the site of an emblem glyph and other prestigious titles (elk'in kalomte’ or “kalomte’ of the east”). The latter title may indicate that Nakum elites had some areas located in eastern Peten and western Belize under their political and cultural control, or that they aspired to have such control. These political aspirations toward the end of the Classic period are also seen in the iconography of one of the central Nakum buildings—Structure G, which possibly served as an audiencia—a place of receiving guests by local monarchs. Its façade was embellished with stucco representations of two captives accompanied with glyphs. These sculptures indicate that Nakum lords, for the first time, gained this distinguished privilege to depict captives in public art. One of them is accompanied by a title that can be read as 9 tzuk or “9 province,” which may refer to the region of northeastern Peten and neighboring Northern Belize (Helmke et al. Reference Helmke, Awe, Morton and Iannone2015:26–28). All these data indicate the changing geopolitical relations in the southern Maya lowlands, which during the Terminal Classic period experienced the shift of borders and spheres of influence, and the rise of new powers.

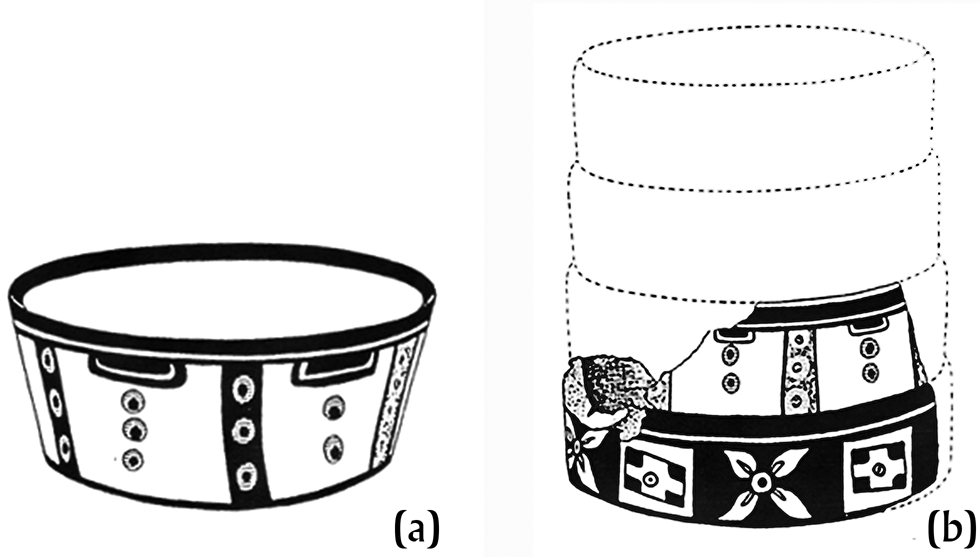

The Terminal Classic period at Nakum, as well as in other Maya centers, is characterized ceramically by the appearance of new wares, the most remarkable of them being Fine Orange ceramics with characteristic molded-carved vessels, which are treated as markers of this period (Aimers Reference Aimers2004; Bishop Reference Bishop and van Zelst2003; Carter Reference Carter2014; Foias and Bishop Reference Foias, Bishop, Varela and Foias2005; Helmke and Reents-Budet Reference Helmke and Reents-Budet2008; Hermes Reference Hermes2019; Sabloff Reference Sabloff and Culbert1973; Smith Reference Smith1958; Ting and Helmke Reference Ting and Helmke2013; Ting et al. Reference Ting, Martinόn-Torres, Graham and Helmke2015). Nakum has in its ceramic assemblage both alleged imported molded-carved ceramics (of the Pabellon Molded-carved type) as well as local imitations represented by the Achote, Azote, Maquina, or Tinaja Groups (Figure 11; Hermes Reference Hermes2019). The iconography of this new category of wares is typically decorated with “confrontation” scenes, similar to many carved monuments of the same epoch (Chase Reference Chase and Fields1983; Graham Reference Graham and Culbert1973; Rice and Rice Reference Rice, Rice, Demarest, Rice and Rice2004:133; Sabloff Reference Sabloff and Culbert1973).

Figure 11. (a) Vessel PANFC 014 (Sahcaba Molded-carved). (b–f) Other examples of molded-carved ceramic fragments found at Nakum. Photographs by Robert Słaboński and drawings by Piotr Kołodziejczyk and Bojkowska.

Apart from small fragments of molded-carved ceramics, the NAP (Nakum Archaeological Project) has also discovered a large fragment of a Sahcaba Molded-carved bowl, found at the southern base of Structure 14 in an ashy matrix midden of Terminal Classic date (PANFC 014; Figure 11a). Associated with this vessel was one radiocarbon sample that returned a date of 2-sigma cal. a.d. 715–940 (1195 ± 30 BP; GdA-2458/PANMC 130; material dated: carbon). The vessel represents a sitting personage, who holds a spear-thrower in his hand and is accompanied by another character—an elderly person bearing a long staff is shown close to the principal figure. The man is facing towards three glyphic columns on the other side, of which we can discern fragments of another sitting individual.

As for the glyphic columns that evenly divide the iconographic registers, these are pseudoglyphic for the most part. In large measure, this is a product of the time and of the social segment producing and consuming these vessels, which were nonroyal elites vying for power in the wake of the weakened or failing institution of royalty. Despite the pseudoglyphic nature of the glyphs, some can be discerned as to their origin, including a circular pet sign at the top, a scrolled ja sign lying laterally on its side, and a bow sign, possibly hi. What is most significant are the three squared cartouches stacked atop one another in the first column. These are evidently emulations of the squared day signs that begin to appear in the written record of the Maya area during the Terminal Classic period. Salient examples can be found at Seibal (Stelae 3 and 13), Jimbal (Stela 1), and Ucanal (Stela 4). In several of these cases, these squared cartouches are drawn from central Mexican signs or are meant to represent the corresponding day signs of the ritual calendar known as the Tonalpohualli (which is analogous to the Tzolk'in calendar among the Maya). In several cases, these squared cartouches do not appear to record dates, but rather name foreign individuals according to their birthdate, an onomastic practice that was well-established in central Mexico and virtually unknown in the Maya area before a.d. 724 (Colas Reference Colas, Helmke and Sachse2014). As such, these square cartouches would appear to name a group of foreigners, possibly also represented in the imagery of the bowl. This follows the practice seen at other lowland Maya sites, such as Seibal and Chichen Itza, where foreigners are named in associated captions in their own writing system.

There are many other molded-carved fragments found at Nakum dating back to the Terminal Classic period. One of them is identical to a ceramic specimen found at Uaxactun, as noted by Martin (Simon Martin, personal communication 2019). These fragments are so comparable that one may suggest that they were made from the same mold. This need not imply a connection to Uaxactun, however, but rather possible participation in the same greater network wherein such molded-carved ceramics were produced, exchanged, and consumed. Similar examples of Terminal Classic ceramics made from the same molds are attested for El Zotz, Tikal, Uaxactun, and Yaxha (Carter Reference Carter2014:290–291; Helmke and Reents-Budet Reference Helmke and Reents-Budet2008).

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

We have only a few Classic-period ceramics with glyphic texts that are mostly associated with the Late Classic ceramic complexes dated to ca. a.d. 600–800. The ceramics presented here, however, show that this is a period of intensive interaction between Nakum and its peers, when nonlocal ceramics also appeared at the site. Rather than equating ceramics with people, as has often been done in archaeology as an unconscious heuristic device in interpretative analogy, we do not see these vessels as implying foreign, or even external, presence at Nakum. Instead, we see these particular vessels as singular moments in time, as significant objects that were gifted, traded, bequeathed, and inherited by a very small segment of society to foster bonds of friendship, amity, marriage, and alliances between distinct royal households. Whether the original owners were even present at Nakum is unknown, but these ceramics serve as highly illustrative and tangible proxies of human interactions, conveying not only their proprietorship, but also the heavily charged symbolism that these ceramics display. Rather than serving as a means of reconstructing borders per se, we see a much more fluid system of allegiances wherein discrete settlements emerged as polities during periods of political autonomy. That being said, the ceramics presented above are tangible testimony to the political interactions and patterns of allegiances that Nakum negotiated during the course of the Classic period.

Based on the present collection, we may make some preliminary attempts to reconstruct the changing fortunes of the history of Nakum. The style of the vessels presented in this paper and the texts that accompany them indicate the existence of complex cultural and perhaps even political bonds between Nakum and other powerful neighbors. Thus, this collection complements our otherwise superficial knowledge about the history of Nakum during the Classic period, which is mainly based on the reading of a few carved monuments. Although our interpretations should be considered as preliminary, it is clear that in the first part of the Late Classic period, Nakum was more oriented politically and culturally toward Naranjo (possibly as its vassal). Nevertheless, during the Tepeu 2 phase (ca. a.d. 700–800), Nakum seems to have fostered stronger ties with Tikal. This possible change in political orientation might have been partly due to the victory of Tikal over Calakmul in a.d. 695, followed by the triumph over its allies, including Naranjo (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008:44–45, 49, 78–79). Other evidence of cultural and architectural ties that might have existed during the Tepeu 2 phase between Nakum and Tikal might be also seen in the largest Nakum pyramidal-temples, the relatively slim and soaring Temple U at Nakum (and also the much later Temple C) which is very similar to the famous Tikal temples, especially to Temples I and III.

During the Terminal Classic period, the situation changed dramatically in the region. The demise of the regional powers such as Tikal and Naranjo created a political and cultural vacuum that was partially filled by Nakum and its high political aspirations. Nakum initiated an energetic program of commemorating carved monuments with depictions of local lords using prestigious titles, exchanging ceramics with other important Terminal Classic centers, and realizing large architectural programs (Helmke et al. Reference Helmke, Martin, Źrałka, Zych, Koszkul, Rusek, Velásquez, Arroyo, Méndez and Ajú2018; Źrałka and Hermes Reference Źrałka and Hermes2012). It seems that the site might have at least partly controlled some territories that once were under the influence of Tikal and Naranjo. This success was short lived, however, for Nakum as a settlement seems to have been almost completely abandoned by the end of the tenth century.

RESUMEN

Investigaciones recientes llevadas a cabo en el sitio maya Nakum, ubicado en el noreste de Guatemala, han llevado a descubrir una gran colección de artefactos de cerámica. Este importante conjunto, aparte de la cerámica monocromática, incluye fragmentos de vasijas policromas que están decoradas con elaboradas escenas iconográficas y textos jeroglíficos pintados. La mayoría de ellos datan del período clásico tardío (ca. 600–800 d.C.), que representa el florecimiento de la civilización maya precolombina. También hay un grupo de cerámicas interesantes que datan del período clásico terminal (ca. 800–900 d.C.) que en la mayoría de los casos se hicieron con moldes y exhiben contenido glífico o pseudoglífico. El estilo de la cerámica presentada en esta contribución, en complementación por análisis mineralógicos y fisicoquímicos de las muestras de cerámica, indican que Nakum fue parte de una red amplia y compleja de interacciones políticas y económicas entre varios sitios y entidades políticas de las tierras bajas del sur, durante el período clásico. Durante la primera parte del período clásico tardío, parece que Nakum tuvo una estrecha relación con Naranjo, probablemente sirviendo como vasallo al menos desde el reinado de su rey de renombre “Aj Wosal.” Varios fragmentos de vasijas encontrados en Nakum parecen haber sido producidos en talleres de cerámica patrocinados por este rey de Naranjo. Después de la victoria de Tikal sobre Naranjo en la primera parte del siglo VIII, Nakum muestra conexiones culturales y políticas más estrechas con Tikal. Sin embargo, hacia el final de la era clásica, cuando observamos el profundo colapso de la civilización maya de las tierras bajas, las élites de Nakum obtienen independencia política de sus antiguos señores. En consecuencia, observamos muchos programas arquitectónicos importantes en Nakum, y la comisión de varios monumentos tallados, que aparecen con prestigiosos títulos y símbolos de poder.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The preparation of this article was possible thanks to research funded by the National Science Centre (NCN), Poland under the agreement no. UMO-2014/14/E/HS3/00534. We would like to thank Christina Halperin and Carolyn Freiwald for their kind invitation to participate in this Special Section of Ancient Mesoamerica. Thanks are also due to the three anonymous reviewers whose comments significantly benefitted our paper.