On the appointed evening he presented himself at the palace of the Grand Duchess radiant with satisfaction. The sight presented to him by these apartments – thronged with all the aristocracy and beau monde of the land, glistening with the jewellery of the ladies and the decorations of the gentlemen, chequered with the bright colours of uniforms and ball-dresses, and enveloped in an atmosphere of charming yet sobered elegance – was such as he had never before gazed on. … His whole thoughts were how to hold his own among that brilliant throng, and win in his own special sphere the distinction that belonged to him.Footnote 1

Thus, in the winter of 1852/53, Michael Balfe made his first appearance before the high society of St Petersburg at a soirée of Grand Duchess Yelena Pavlovna, the German-born sister-in-law of Tsar Nicholas I. Judging by the words of his biographer Charles Lamb Kenney, this must have been an extraordinary occasion for the Irish composer. Even so, it was an experience he had in common with many of his musical colleagues. With possibly the most magnificent court in nineteenth-century Europe, a select group of aristocrats of extraordinary wealth, and a broader noble public eager to hear the latest European stars, Russia was a ‘gold mine for artists’, as Turgenev put it.Footnote 2 Its two capitals, St Petersburg and Moscow, attracted great numbers of musicians from abroad, and their Russian sojourns, whether long or short, invariably involved encounters with the upper echelons of local society.

This article takes as its subject these interactions of visiting musicians with the Russian court and the aristocracy in St Petersburg and Moscow during the reigns of Tsar Nicholas I (1825–1855) and Alexander II (1855–1881). I approach these contacts principally from the musicians’ perspective, asking how they experienced the world of Russian high society, how they coped with these elites in their various capacities – as hosts, audiences, mediators, patrons and gatekeepers – and how we can understand the significance of these contacts in their professional lives. Aimed at understanding the social relations that permeated musical life, this investigation demonstrates the persistent significance of court and aristocracy in the middle decades of the nineteenth century and shows how reports of musicians’ appearances at court tended to validate the existing social order.

The relevance of nineteenth-century courts and aristocracy for travelling musicians is a topic that has received little attention as such. It is situated at the intersection of two existing areas of research: the relatively recent work on musicians’ travels and the much older study of professional musicians’ relations to court and aristocracy.Footnote 3 The latter has traditionally been approached as a process of emancipation – a transition from ‘princely service to the open market’, as John Rosselli phrased it – which is by and large considered to be complete by the early nineteenth century; hence, the period here under consideration has attracted much less systematic attention.Footnote 4 The topic also falls partly outside the purview of what is commonly studied as patronage, since it involves visitors whose contacts with the local elites were often of a temporary nature and did not always entail active support.Footnote 5 Hence, attention for musicians’ dealings with foreign elites has mostly been left to studies of individual musicians, leaving the patterns exhibited by the continuous flows of travellers largely unexplored.Footnote 6

As ‘the last surviving eighteenth-century (hierarchical, aristocratic) society in Europe’ and a major attractor of musical talent, Russia makes for a particularly interesting case study.Footnote 7 Many aspects of musicians’ visits discussed below – the economy of gifts, honours and recommendations, the status associated with appearing at court and its relevance for success in public performances – were not unique to Russia and may be profitably compared with other musical centres.Footnote 8 The roles of the court and aristocracy in Russian musical life did stand out with particular relief, however, and contemporary reports frequently noted their unusual prominence and splendour. Given the prevalence of the Russian stages in musical careers, these contacts ought to be seen as integral to the European musical landscape, and can tell us much about how musicians of this period related to monarchy and aristocracy in general.

Inevitably, there is a dimension of international politics to this topic. The decades leading up to and following the Crimean War (1853–55), were characterized by strong currents of Russophobia in Western European public opinion, the most famous instance of which was Marquis de Custine's scathing review of Russian society under Nicholas I, which became an international bestseller.Footnote 9 The stereotype of Russia as an essentially ‘Asiatic’ and dangerous power was widespread and would periodically resurface regardless of rapprochements in international relations.Footnote 10 It should be kept in mind that the many musicians who crossed the continent to perform and teach in Russia did so against this background. The sources discussed below, however, suggest that despite the cultural and political differences – real and imagined – on the whole, they developed a positive, reciprocal relationship with the Russian elites, and their reports about Russian high society contrast with the more familiar exoticized image of Russia as a country of steppes and melancholy.Footnote 11

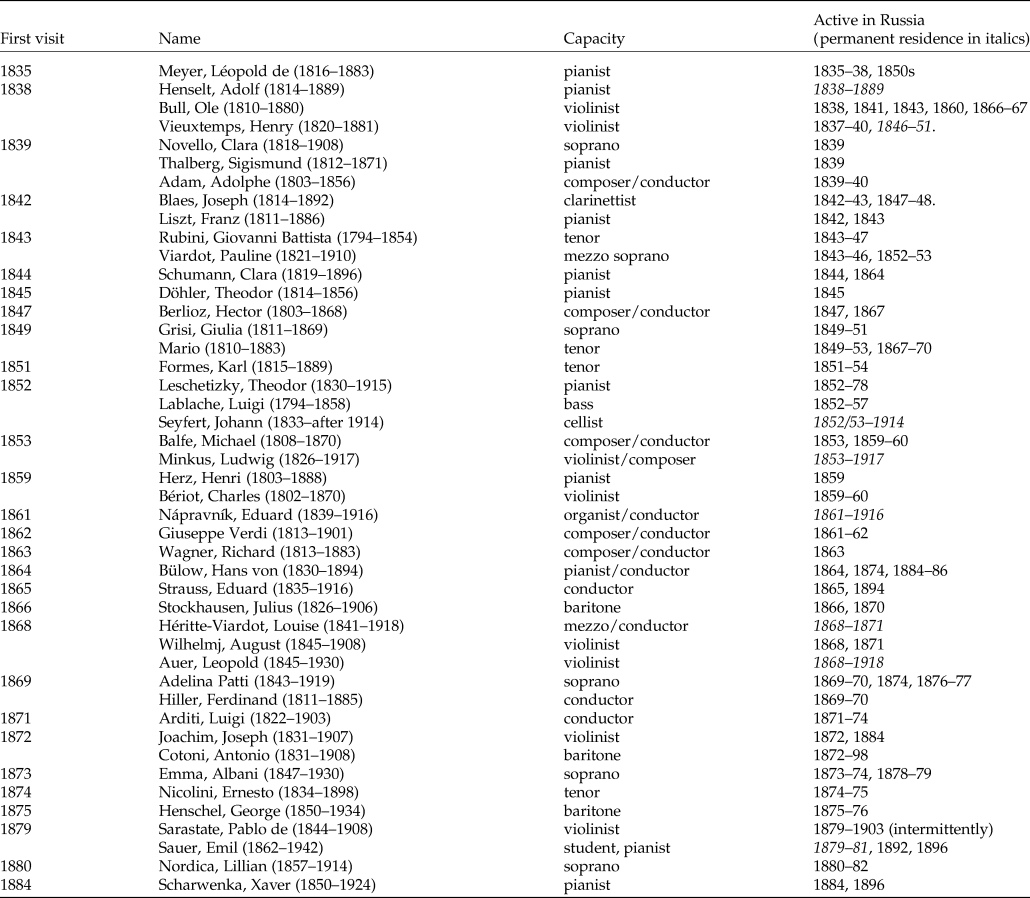

At the core of this project is the voluminous body of contemporary letters, diaries, memoirs, travel reports and biographies, which, like Kenney's biography of Balfe, made note of the sumptuous life at court, the elevated personages musicians encountered, their success or failure, and every now and then, their concerns over making a faux pas in these circles.Footnote 12 The discussion below will be focused mostly on the Imperial court and the ‘small courts’ of the grand dukes and duchesses, along with a number of aristocratic patrons and high officials who feature most prominently in musicians’ reports. By practical necessity, I have also limited myself to conductors and soloists, whose experiences are not only better documented than those of rank-and-file orchestral musicians and teachers, but who also had better access to the social elites and who, due to their prominence, were in a better position to contribute to the image of Russia in public discourse.Footnote 13 The musicians referenced in the article (footnotes included) are listed in Table 1.

Table. 1 Visiting Musicians Referenced in the Article and the Period of their Activity in St Petersburg or Moscow

I begin my analysis by discussing the tensions between the social status of successful musicians and Russia's hierarchical society, with particular reference to the courtly dimension of the Italian Opera; next, I will turn to the role of the aristocracy and court in the organization of public concert life under Nicholas I, and examine the relevant changes and continuities under Alexander II, the period of major reforms and significant institutionalization of musical life. Following this survey, I consider the rewards the Russian court and aristocracy could offer – including the gifts, titles and decorations that usually attract little attention in music historiography – and argue for the persistent significance of imperial and noble recognition, which prompted visiting musicians to view and represent the world of the Romanovs in a notably favourable light.

Independence and Service

The notion of the musician's emancipation from royal and aristocratic patronage is one of the central narratives of traditional music history. Ludwig van Beethoven is probably the paradigmatic example, and during his lifetime we can see successful musicians proclaiming their independence from aristocracy and court – refusing to be treated with condescension, protesting against people chatting, eating or playing cards during private performances, and challenging seating arrangements during dinners. Given the significance that is usually attached to the developments in this period around 1800, it is all too easy to take them in too definitive or absolute terms and underestimate conservative forces in the remainder of the nineteenth century.Footnote 14 If we view the late eighteenth century as a ‘period of transition’, it is rather unclear when this settled into a new status quo.Footnote 15

Conditions in Russia were far from conducive to the growing independence from court and aristocracy that musicians were experiencing elsewhere. The Russian Empire had a highly hierarchical social structure, inherited from the eighteenth century and composed of hereditary estates (sosloviya) and ranks associated with service in the army, bureaucracy or court (chinï). At the very top of the hierarchy, below the tsar and the imperial family, was an aristocracy made up of the wealthiest landowning families, an elite that also supplied most top positions in state functions and the military.Footnote 16 Within the stratified structure of Russian society, musicians had no recognized legal position, at least until Anton Rubinstein managed to secure the status of ‘free artist’ (svobodnïy khudozhnik) for conservatory graduates in 1861; and even then, as Lynn Sargeant has shown, it remained relatively weak and contested.Footnote 17 Before that time, their social standing depended on either birth or state service; and, due to the institution of serfdom, abolished under Alexander II in the same year of 1861, it was relatively common for the Russian aristocracy to maintain private ensembles or orchestras of serf musicians on their estates. As a result, both the idea of the musician as more than an artisan and that of the pre-eminence of the public over the private domain found relatively late acceptance in Russia.Footnote 18

Musical life in Russia's two capitals was also highly centralized and strictly regulated. The Imperial Theatres, which were administered as part of the court, exercised an official monopoly over theatrical performances in St Petersburg and Moscow from the 1840s, and concerts and other musical entertainments were permitted only at their discretion.Footnote 19 There was little room for the open market or entrepreneurship often associated with musicians’ emancipation from aristocratic and court patronage, nor could there be a notable middle-class influence on musical life, as Russia's middle classes remained small and fragmented before the reforms of the 1860s.Footnote 20

In various respects, then, St Petersburg and Moscow differed substantially from an important musical centre such as London, which was known for its unregulated and commercial musical life.Footnote 21 In order to attract the latest stars, however, they had to offer comparable treatment and competitive rewards, and it was through this international market, that changes in the social status of musicians elsewhere made themselves felt in Russia, too.Footnote 22 This had at least two important social consequences: first, there was a remarkable split between the status of local and foreign musicians; and second, Russia's old-fashioned, hierarchical society would be confronted with the new values and self-image of visiting artists – and vice versa – which was a potential source of friction.

In some exceptional instances, musicians’ social pretensions and the values of Russian elites came into open conflict, as in the scandal surrounding Austrian pianist Theodor Döhler. After a successful season in St Petersburg and Moscow in 1845, Döhler was so bold as to make a marriage proposal to a Sheremetev. This match would make the ‘piano half-celebrity’ an in-law of one of the richest and most influential men in Russia, which, as one noble memoirist recalled, ‘aroused a loud and of course disapproving anxiety in the highest aristocratic strata of society’.Footnote 23 Tsar Nicholas himself intervened and forbade the wedding, regardless of the bride's mother's consent. After Döhler was made a baron by his old patron, the Duke of Lucca, however, he was allowed to marry Sheremeteva, on the condition that he would refrain from public performances in Russia, which effectively ended his career as a pianist.Footnote 24

Most musical interactions, of course, did not strain relations to this extent, but a palpable class barrier would often separate musicians from their noble hosts.Footnote 25 Writing about Anton Rubinstein's time in the 1850s as a musician-in-residence at the court of Yelena Pavlovna – a position Rubinstein himself found demeaning, describing his role as that of a ‘musical stoker’Footnote 26 – a lady-in-waiting of Empress Aleksandra Fyodorovna remarked how members of the aristocracy tended to treat artists with an air of ‘patronizing benevolence’. She sympathized with the artists, but also felt highly uncomfortable in their presence: ‘whenever there is but one of them in the room, I no longer feel free’.Footnote 27 For foreign celebrities, who were not subject to the Russian crown, interactions with the elite were less constrained by the Empire's class system, but the social differences would typically require both the visitors and the hosts to adapt.

Of all forms of noble involvement in the arts, private employment by courts and aristocracy was arguably the most at odds with the nascent notion of the musician as an independent artist, and also the most notably in decline. To be sure, the Imperial Court, the grand-ducal small courts and the Russian nobility continued to hire both native and foreign musicians as performers and teachers. Around the middle of the century, Prince Nikolay Borisovich Yusupov still attracted a series of distinguished foreign chapel masters for his private orchestra, which included Ludwig Minkus in the 1850s, Charles Bériot in 1859–60, and Eduard Nápravník in 1861–62. Tellingly, however, none of these musicians were in the prime of their careers: Bériot, the founder of the Franco-Belgian violin school, was blind by the time Yusupov hired him; and both Minkus and Nápravník would move on to make a name for themselves in Russia's public arena, Minkus as a ballet composer and Nápravník as the conductor of the Mariinsky Theatre. Such positions of a private rather than public nature could still provide important stepping stones in a musical career, but they no longer matched the aspirations of the more ambitious artists.Footnote 28

If it could be combined with public activity, however, association with the Russian court continued to hold a definite appeal. In the 1850s and 1860s, Yelena Pavlovna hired talented foreign artists to manage her musical affairs, such as the Austrian-Polish pianist Theodor Leschetizky and Louise Héritte (Pauline Viardot's daughter), who both combined their function with teaching and performance outside court.Footnote 29 The Hungarian violinist Leopold Auer, who was offered a position as soloist at the Grand Duchess's court in 1868 alongside a post as professor at the St Petersburg Conservatory, implied in his memoirs that the former was the more exciting prospect: ‘Anton Rubinstein had begun his career at this court’, he wrote – apparently unaware of Rubinstein's own dissatisfaction – ‘do I need to add that my deliberations were brief?’Footnote 30

In order to understand both the appeal and the inherent tensions of foreign musicians’ relations with Russian court circles, the Italian Opera, established as a prestige project by Nicholas I in 1843 and abolished under Alexander III in 1885, can serve as a special case study. In his study of the profession of Italian opera singers, John Rosselli noted how, ‘as opera shed its function of mirroring court life … singers need no longer pretend to be courtiers’ – a process he situates in the eighteenth century.Footnote 31 In Russia, however, the association between court and opera remained strong. Since the Imperial Theatres (to which the Italian Opera belonged) were administered by the Ministry of the Court, its performers – which included many of the finest singers in the world – were in principle members of the tsar's personal retinue. Its top performers often received additional appointments as Soloists to the Court, which gave them various privileges, including the right to wear an official Russian court uniform (vitsmundir). Giovanni Battista Rubini, one of the first to be so honoured, ‘clearly cherished this right’, as one contemporary recalled, prancing around in his uniform tailcoat at his concerts.Footnote 32 And even though soloists tended to divide their time between St Petersburg and other houses with different seasons, artists of the Imperial Theatres were expected to participate in court ceremony when called upon, such as in 1856, when the season of the Italian Opera started early for six weeks of festive performances in Moscow on the occasion of Alexander II's coronation.Footnote 33

Their status as foreigners gave the performers of the Italian Opera decided advantages over local musicians. This was expressed most explicitly in their payment, which could vastly exceed the legally established pay scales and composition fees for subjects of the Russian crown.Footnote 34 For the happy few, it could also involve an unusual proximity to the Imperial family. Cecilia Godfrey Pearse, the daughter of soprano Giulia Grisi and tenor Giovanni Mario, wrote:

As society in St. Petersburg in those days consisted exclusively of the Czar and his family, the numerous Grand-Dukes and their families, and all the Court officials and their relations, the Opera was more a Court function than it is now, and the performances as well as the concerts given in the Winter Palace, or in the other palaces of the Imperial family, provided more opportunities of intimate and friendly intercourse between the Court and the singers than would have been possible under ordinary conditions.Footnote 35

Godfrey Pearse's own experiences as a girl underscored this: when her mother died in 1869, at the start of a new Russian season in which her father was to appear, she and her sisters were taken into the care of intimates of the court and spent much time as guests in the Winter Palace.Footnote 36

Artists did require the appropriate social skills and cultural capital to navigate this environment, but those who possessed them could be adopted into the inner circles of Russian high society. The bass Luigi Lablache, who performed in St Petersburg in his late career between 1852 and 1857, was a regular at the soirées of the Russian foreign affairs minister Karl Nesselrode, and was praised for his ‘manners of a rare distinction’ and his ‘frank and communicative cheerfulness’, which ‘made him the focus in all the salons he attended’.Footnote 37 He became enough of an intimate for a small diplomatic scandal to occur: while settling the terms at the end of the Crimean War, Nesselrode spilled the news of the accepted peace offer to the singer, who then passed it to a Neapolitan diplomat before it had been communicated through the proper channels.Footnote 38 Still, as Rubinstein recalled, the introduction to court was a stressful affair even for someone like Lablache. During his first visit to a musical gathering of Yelena Pavlovna, the portly singer was caught in a situation where his hostess, and then the Empress, repeatedly implored him to sit, but the sudden entrance of Tsar Nicholas caused him to jump up in shock. Confused either by the breach of etiquette or by the kindness of the tsar's greeting, he was completely flustered:

Lablache, the old man, who had seen it all, who … was distinguished by full independence, was himself a king – this Lablache began to stammer, and could not say two words. Such a face and posture Nicholas Pavlovich had. They were very kind to Lablache at court afterwards.Footnote 39

In spite of the sweeping claims made on behalf of them, obviously, musicians continued to feel dependent on the benevolence of the court. And their integration into court affairs, though often considered an honour, could well run counter to Romantic ideals of artistry and stardom. This was most obviously the case with their participation in court ceremonies, such as the wedding festivities of the Duke of Edinburgh and Grand Duchess Mariya Aleksandrovna in 1874. Luigi Arditi, the conductor of the Italian Opera, composed a cantata for the occasion, which was performed at the Winter Palace by, amongst others, Adelina Patti, Emma Albani and Ernesto Nicolini, and ‘drew forth great enthusiasm from the Imperial and Royal assembly’.Footnote 40 Albani recalled it as ‘a scene the magnificence of which I can never forget, combining as it did the modern perfections of Western civilisation with the remains of the barbarous splendour of oriental life’.Footnote 41 Amidst this splendour, however, the artists of the Italian Opera were used as mere dinner entertainment, singing as the 600 guests were eating and where, as protocol dictated, a fanfare followed by a volley of cannons could interrupt the singers mid-aria to announce a toast. When this happened to superstar Adelina Patti, it brought the diva to tears.Footnote 42

Even visiting musicians of the highest international standing, then, would at times receive clear reminders of their subordinate position. Though the artists of the Italian Opera were bound to contractual agreement as elsewhere in the opera world, there are many incidents and anecdotes about the tsars exercising their personal authority over them or granting them extraordinary privileges. Mario, an unmistakable favourite of the Imperial family and Russian audiences, was supposedly caught smoking illegally on the streets of St Petersburg by Nicholas I himself (and then granted special permission to do so), and commanded to shave off his beard for a performance (which ended with his departure).Footnote 43 When the British soprano Clara Novello – who did not perform at the opera and was therefore not bound to any seasonal agreement – indicated she would leave Russia due to illness and the risk of losing her voice, Aleksandra Fyodorovna replied: ‘Not when the Empress desires you to remain, mon enfant’.Footnote 44 While these exercises of power often remained symbolic gestures – as in the case of Novello, who was soon dispatched with an express coach and a handsome gift from the Empress – they did recall the arbitrary treatment of artists in earlier centuries.Footnote 45 Not all such stories, to be sure, are equally reliable (a question I shall return to below), but they do unmistakably express the discomfort of operating in an autocratic environment.

The position of foreign musicians close to the court, in short, was pervaded by a sense of both privilege and insecurity. The way successful musicians were received in Russian elite circles testified to their improved social status and independence abroad. Still, even for privileged foreign stars, this continued to produce a notable field of tension with the social hierarchies and courtly traditions of Russia's autocratic regime, which both the visitors and their hosts would have to negotiate.

Public and Private Access

It is no exaggeration to state that in the time of Nicholas I, the court and aristocracy were dominant forces behind essentially all aspects of musical life that mattered to musicians from abroad. Their involvement was not restricted to private employment or the engagement at the crown theatres discussed in the previous section, but also extended to the world of concert tours by travelling soloists undertaken as individual enterprise, where we see a different mechanism at work.

Tellingly, apart from the crown theatres, the most prestigious halls in St Petersburg and Moscow were those of the Nobility's Assembly. Though renowned in the chronicles of music history (the St Petersburg venue is the current Great Hall of the Philharmonic), in the mid-nineteenth century, these were not dedicated concert halls but served a variety of purposes, including balls, masquerades and other charity events.Footnote 46 As Hector Berlioz recounted regarding his visit in 1847, the regulations of the Nobility's Assembly in Moscow stipulated that any artist wishing to use their grand hall was required to perform at one of the private gatherings of the aristocracy first, which illustrates the extent to which the world of public performance was subordinated to the interests of the elite.Footnote 47

Practically all successful sojourns by foreign soloists involved socializing with and performing at the homes of the elite, who, as a result, were much more than an anonymous audience. It was widely recognized that such visits were essential for successful public performances.Footnote 48 As the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung reported about St Petersburg in 1831:

the artist has to be here at least a month before the concerts start, so he has time to perform in various private circles first, which is necessary, for this will, should he gain approval, make it better and easier to sell his entrance tickets; generally, one does not count on the box office here at all.Footnote 49

It was common practice for wealthy nobles and officials to buy many more tickets than just for themselves and their families: in one case, Prince Dmitry Golitsïn, governor of Moscow, bought 200 tickets for a single concert.Footnote 50 On occasion they would also voluntarily pay more than the advertised price.Footnote 51

High society could prove reluctant to participate without approval of the court, which made success at court, with the aristocracy, and in public performances highly dependent on each other. Consequently, an audience at the Imperial court was a crucial step in many concert visits. Clara Novello, who visited St Petersburg in 1839, even considered the Empress ‘the main object of our coming’.Footnote 52 But access to court was never a given, as Novello found.Footnote 53 Few could count on the privileged position Franz Liszt enjoyed on his first tour to Russia in 1842, when he received an immediate invitation to court for the day after his arrival, and could boast on his first night that he would not touch a key before he had made his appearance there.Footnote 54 This, in turn, paid off in his public performances: when the Emperor showed him the honour of attending his second concert in the Hall of the Nobility's Assembly, the virtuoso suspected – probably rightly so – that this was the reason for higher attendance compared to his first.Footnote 55

The experiences of Clara Schumann during her first visit of 1844, which have been documented in unusual detail, might serve as a more representative illustration of the complexities that attended this organization of musical life. In the travel diary she shared with her husband Robert, the couple practised a form of ‘social bookkeeping’: extensive listings of important new relations, which allowed them – and us – to keep track of their evolving social network.Footnote 56 These listings included various musical colleagues – predominantly Germans, with the important exception of Clara's friend Pauline Viardot – as well as many members of elite society. Table 2 shows the Schumanns’ meetings with Russian nobles and high officials over the time of their stay. In various cases, they recorded how worthwhile these contacts had been, which also included some disappointments: Prince Sergey Golitsïn, for instance, ‘was of no use to us, on the contrary, he cost me a pair of gloves and Robert 3 silver roubles (for the carriage), but had invited us only to say “good day”’; and about Baron Alexander von Stieglitz, the tsar's banker, she noted: ‘nice dinner – but not very nice businesspeople. This man owns 40,0000 [sic] – and after I brought him 4–5 letters took only 10 tickets for my first concert – that was all!’Footnote 57 Musicians invested much of their time and energy into making their rounds of visits, and obviously did so with certain expectations, but convention still dictated that these expectations remained unstated and that the yield of these visits depended entirely on the generosity of their hosts.

Table. 2 Selection of the Schumanns’ contacts with Russian nobility and high officials, as recorded in their diary during their 1844 stay in Russia. Noted are visits, first meetings and gifts. Any documented letters of recommendation delivered to a contact are marked with ↑ (on the date of their first visit); and any documented letter provided by a contact are marked with ↓ (on the date acquired, or if unknown, at the last possible encounter). Dates are according to the Old Style (local) calendar.

It had taken Schumann several weeks to gain access to court, much to her frustration. ‘If I had played to the Empress immediately at the beginning, I would have had much better concerts’, she complained; ‘in St Petersburg everything must come from court, if the nobility is to participate’.Footnote 58 The study of patronage shows that in many cases, access to the upper echelons of society would work through ‘a kind of graduated scale of prestige for salons’ in which ‘a musician sought to matriculate by introduction from one salon to the next rung up’.Footnote 59 However, for touring musicians who had to make their mark within the short St Petersburg concert season, which in the Nicholaevan period was restricted to the 40 days of Lent when the theatres were closed, there was scarcely any time to move through such steps.Footnote 60 It was essential, therefore, to pave the way from abroad to gain more direct access to the upper echelons of musical life: one needed prior relations, sometimes bolstered by the dedication of a composition, and always by letters of recommendation.Footnote 61 Clara Schumann had already conceived of going to St Petersburg as early as 1839, and had wasted no time in making plans for acquiring recommendations.Footnote 62 In the spring of 1840 she jumped at the opportunity of playing before Nicholas I's wife, Empress Aleksandra Fyodorovna (1798–1860), first at the Prussian court, which fell through as Aleksandra's father, King Frederick William III, was terminally ill; but later that year she performed successfully at the court of Weimar, where the Empress visited her sister-in-law, Grand Duchess Mariya Pavlovna.Footnote 63 That winter she also met Aleksey L'vov (1798–1870), a key player in Russian musical life, as the director of the Imperial court chapel, the composer of the Imperial hymn and aide-de-camp of Nicholas I. When the Schumanns arrived in St Petersburg, they carried letters from their network of fellow clients, which included Mendelssohn and Liszt, as well as from a network of patrons, which included the Grand Duchess of Weimar's chamberlain, Prince Metternich – to which Clara was automatically entitled as Kammervirtuosin to the Austrian Emperor – and their own queen, Maria Anna of Saxony, who was related to the Romanovs through her nephew the Duke of Leuchtenberg, the husband of Grand Duchess Mariya Nikolayevna.Footnote 64

In the mid-nineteenth century, royal letters of recommendation still carried considerable authority and practical value, even for public figures such as the Schumanns.Footnote 65 Through the marriages of the Romanov family, there were various other courts in Europe that musicians typically turned to before heading to St Petersburg. Berlin was the most common stop before a visit to Russia owing to the family ties of Aleksandra Fyodorovna.Footnote 66 These family relations also made it worthwhile to visit smaller courts like that of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, where the Grand Duke, Paul Frederick (1770–1840), was related to the Romanovs through his mother, and his wife Alexandrine was the younger sister of Prussian King Frederick William IV (1795–1861) and Empress Aleksandra. Thus, it could happen to the Norwegian violinist Ole Bull that, while in Kiel in 1838, he received an invitation to play in Schwerin, thanks to his contacts with the Princess of Orléans, who was half-sister to the Grand Duke; and after he had performed there, Grand Duchess Alexandrine could refer him to both Berlin and her sister in St Petersburg.Footnote 67

Such royal recommendations could in fact provide the very impetus for going to Russia. Michael Balfe only decided to go after he was offered a letter by Aleksandra Fyodorovna's younger brother, the Prussian Prince Charles, and her nephew, the future Emperor William I.Footnote 68 And the Belgian cellist Adrien Servais, who would make a small fortune from his many travels to Russia, seems to have gotten the idea of heading east when playing at the Dutch court in The Hague in March 1837, where the opportunity presented itself of collecting a letter of recommendation from Anna Pavlovna (1795–1865), sister of Nicholas I and wife of the Crown Prince of the Netherlands.Footnote 69 As the dynastic ties shifted over the course of the generations, so did the obvious places to pass through before heading for Russia. In the 1880s, for example, we see travellers picking up letters at the Danish court in Copenhagen, since their Princess Dagmar had married Alexander III.Footnote 70 This network of royal affiliations guided musicians in choosing their itineraries, with obvious consequences for the locations of their public performances as well.

It should be noted that letters to the Imperial court alone, generally, did not suffice. Upon arrival, the local aristocracy – for which one also brought letters – would have to offer additional routes of access into court and musical life. Table 2 above also indicates the documented letters of recommendation delivered to and supplied by local notables, which undoubtedly represent but a fraction of the ones actually handed over, but shows how the Schumanns established a foothold in Russian society, and how their new Petersburg acquaintances later referred them to Moscow. Among their first contacts were two men who played a crucial role in St Petersburg's musical life in the 1840s: Count Mikhail Wielhorski (1788–1856) and his brother Matvey (1794–1866). Well informed, well connected, favoured by Nicholas's court and both skilled amateur musicians, the Wielhorskis acted as gatekeepers, mediators and advisors to visiting artists.Footnote 71 In his younger years Mikhail had been abroad recruiting singers for the Italian opera, and he acted as advisor for invitations made by others.Footnote 72 Berlioz dubbed Wielhorski's home on Mikhaylovsky Square, which could host an orchestra, ‘a little ministry of the fine arts’.Footnote 73 Over the years, many would first prove their worth in his salon, where they would be introduced to other relevant players in musical life, before being invited at court or venturing to give public performances.Footnote 74 Though Wielhorski's contribution to St Petersburg's musical life has often been praised, this system, in which a position as dominant authority in musical life was entrusted to an individual dilettante, also carried obvious downsides, as the violinist and composer Nikolay Afanas'yev pointed out: ‘All artists who wanted to acquire themselves a position in Petersburg, had to appear in the musical salon of the Count: otherwise they would not be recognized and they would not be able to do anything’. Afanas'yev also claimed that Mikhail Wielhorski received ‘an allowance of 15 thousand [roubles] from our sovereign, designated as an incentive for artists’. Without having to go into the question of ‘whether the virtuosos performing at the Count's received anything from the sum designated as an incentive for them’ – which Afanas'yev doubted – it is interesting to note that such a subsidy would lend Wielhorski's salon the official character Berlioz implied in his famous phrase.Footnote 75

The Schumanns, too, were invited to a Wielhorski soirée soon after their arrival, and the brothers visited them regularly throughout their stay, but let them down as regards the access to court. ‘Wielhorski kept saying that I should only keep waiting calmly, things will work out at court, the Empress is just ever unwell; so I could still wait for a long time’, Clara complained. In the end, it was Adolf Henselt, a pianist well connected to the court, who ‘went straight to the source’ and called on the singer Praskov'ya Barteneva, one of Empress Aleksandra's ladies-in-waiting, which, it seems, settled matters rather quickly: within two days, Clara received her invitation to court – through Wielhorski.Footnote 76 Her performance there was a success: she was charmed by the kindness of the Imperial family and celebrated afterwards with Robert. Her final concert at the Mikhaylovsky Theatre the next Friday, before leaving for Moscow, was attended by the court and drew a full hall. The ensuing profit of 1,000 silver roubles finally made their stay in St Petersburg worthwhile.Footnote 77 Though surely a credit to her artistry, this success depended in no small measure on the extensive investment in social connections before and during the stay.Footnote 78

Continuity and Reform

While the association of the Italian Opera with the court largely continued as before, the organization of concert life would undergo various profound changes as it resumed its course after the death of Nicholas I and the end of the Crimean War in 1855. Most importantly, the climate of reform under the new emperor Alexander II allowed for the foundation of the Russian Musical Society (RMS, 1859) and the associated Conservatories of St Petersburg (1862) and Moscow (1866), which initiated a steady professionalization of musical life. The transformations effected by these institutions have been studied in detail by Lynn Sargeant, but the consequences for foreign visitors have so far escaped attention.Footnote 79 Prominent musicians were now more likely to come to Russia on the invitation of institutions. The RMS took a notable role in this, although the focus in its first two decades was more on attracting conservatory staff than on hosting touring musicians in their concert series.Footnote 80

This did not put an immediate end to the older structures of patronage and aristocratic mediation, however. The RMS itself operated under imperial protection, later made official by the predicate ‘Imperial’ awarded in 1869. After sponsoring Anton Rubinstein in its establishment, Grand Duchess Yelena Pavlovna acted as the society's first president, and attracted various guest performers and conductors from abroad in ways that straddled the borders of the private and the institutional.Footnote 81 Clara Schumann (1864), Hector Berlioz (1867/68), August Wilhelmj (1868), Ferdinand Hiller (1869/70) and Joseph Joachim (1872) were all invited to stay at the Grand Duchess's residence, the Mikhaylovsky Palace, where she typically cared for their every need, including thoughtful details such as birthday gifts and delivering them the newspaper of their hometown. Hiller was so flattered that he later published recollections of his time in St Petersburg that were largely devoted to his host.Footnote 82 This hospitality, incidentally, did not imply intimate contact or a relationship on an equal footing. The Grand Duchess showed herself only occasionally to her visitors, and during the dinners after a soirée, the aristocratic guests and the musicians typically dined in separate rooms.Footnote 83

While these visits illustrate the continuing relevance of patronal relations, Yelena Pavlovna's unusual level of activity should not mask various important shifts taking place in concert life. By the time of her death in 1873, the Russian aristocracy and imperial family were no longer as active as gatekeepers and attractors of foreign talent. The practice of entertaining private ensembles, like that of Prince Yusupov, did not survive the abolition of serfdom; nor did anyone take up a position like that held by Wielhorski, who had passed away shortly after the war. In the late 1870s and 1880s we see the emergence of a new kind of patron, exemplified by Nadezhda von Meck, Mitrofan Belyayev and Savva Mamontov, whose fortunes derived from business and industry, and who are also better known for their interest in national art and native artists (though it should be noted that Mamontov's Private Opera company was initially led by a succession of Italian conductors, and Von Meck hired young Debussy as a pianist).

Performances at more intimate gatherings at court or aristocratic homes continued to be a common element of concert tours, as, indeed, aristocratic salons elsewhere retained their significance well into the twentieth century.Footnote 84 Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich, a passionate amateur cellist who succeeded Yelena Pavlovna as president of the RMS, received many musicians from abroad on the Friday matinées in his Marble Palace.Footnote 85 The Imperial court presented fewer opportunities than before, however. After losing her eldest son, the Tsarevich Nicholas, and contracting tuberculosis in the mid-1860s, the new empress, Mariya Aleksandrovna (1824–1880), generally kept her musical soirées to small affairs, with a few singers from the Italian Opera and the Soloists of the Tsar, and no more than 20 people in the audience. Alexander II would retreat in an adjacent room and play whist with his courtiers.Footnote 86

As for visits to the aristocracy, the case of the Spanish violin virtuoso Pablo de Sarasate, who came to Russia on the invitation of the RMS in 1879 and returned in several subsequent years, offers an interesting contrast to the experiences of earlier visitors. Auer considered him a ‘good comrade’, who ‘preferred the society of his musical friends to playing in the homes of the wealthy’, which meant he would only appear at an aristocratic soirée if paid ‘2,000 to 3,000 francs, a fee which at that time seemed exorbitant’.Footnote 87 Auer's testimony suggests that it was still exceptional not to make such private appearances, but also – in contrast to the situation under Nicholas I – that these were no longer essential for success on the public stage, and could be offered against predetermined fees.

Material and Symbolic Rewards

The difference between the experiences of the Schumanns in the 1840s and those of Sarasate in the 1870s is significant, for it suggests how the forces of a market, with the use of money and the relatively transparent transactions it enables, were encroaching upon the previous, more obviously asymmetrical system of favours that characterizes traditional structures of patronage.Footnote 88 There is little doubt that money was the prime mover in musical travels to Russia. Both in the press and among artists we find frequent reports of the sensational sums made by famous artists, and as we have seen above, contacts with the Russian elite were instrumental in acquiring these. But money was never the only attraction Russia had to offer, and in order to understand the significance of the Russian court and aristocracy for visiting musicians it is important to consider alternative forms of reward, which, I would argue, are relevant for the entire period here under consideration.

As Myriam Chimènes has stressed in her extensive study of the Parisian salons of the Third Republic, it would be reductive to view the relations between hosts and musicians exclusively from the perspective of professional interests and financial gain. Chimènes notes that, at the very least, musicians ‘sometimes quite simply appreciated being heard, recognized, and, above all, being pampered’.Footnote 89 There is ample suggestion that this applied to visitors to Russia as well. I would like to suggest, however, that in this case, being heard, recognized and pampered carried a considerable symbolic component that is difficult to disentangle from their professional interests, or from the interests of the Russian elite.

Success in Russia carried a symbolic dimension. In the 1830s, we see regular warnings in the Western press, urging musicians not to think too lightly of a Russian tour, given the high costs and strenuous competition.Footnote 90 Such reports did not necessarily make St Petersburg less attractive as a destination: if the economic capital on offer (to put it in Bourdieuan terms) was limited and only the very best could succeed in bringing it home, the city had all the more to offer in terms of symbolic capital – success would carry more status. It is worth comparing Russia to America in this respect: starting in the 1840s, the United States began to surpass Russia as the place where virtuosos could make their fortune, yet many a high-minded European artist remained reluctant to cross the Atlantic, to sell their talent to what they expected to be uncultured audiences in a commercial enterprise.Footnote 91 Contemporary reports about St Petersburg, by contrast, regularly noted how the halls were filled with ‘the highest nobility’, with dazzling dresses and jewellery that made Paris look pale in comparison, which added to the prestige of a performance.Footnote 92 As the value of recognition abroad depended strongly on the respectability and taste of its audiences, I would argue that the aristocratic audiences of the Russian capitals added considerably not only to the country's material but also its symbolic appeal.

At court, visiting artists were generally rewarded with gifts rather than money. Both the musical press and the musicians themselves dutifully reported how they were honoured with sumptuous gifts such as diamond-encrusted rings, brooches, snuffboxes and cigarette cases. The aristocracy liked to present gifts to their favourites as well: Moscow notables sent instrumental virtuosos like Adrien Servais or Ole Bull back home with arrays of souvenirs, and divas of the Italian Opera would often find jewellery inside bouquets thrown on stage.Footnote 93 These practices reflected the nobility's long-standing distaste of the cash nexus, and also, to some extent, how appearances at salons and homes were perceived as private and personal affairs where ordinary payment might be considered inappropriate.Footnote 94 Given the frequency with which the court handed out its precious gifts, it should be no surprise that this was in fact a rather routine affair, managed by the so-called Cabinet of the Emperor, which attended to the tsar's personal expenses, and made sure artists who had performed before the Emperor or Empress received these a few days after their performance.Footnote 95 As Auer revealed in his memoirs, it was in fact possible to return one's diamond ring to the Cabinet and exchange it for an amount in roubles, yet one wonders how many of the short-term visitors would consider this, provided they knew about it.Footnote 96 Many musicians took obvious delight in these gifts and the recognition they represented, which could not simply be translated into monetary value.Footnote 97

The same holds for the elusive world of court honours and distinctions, which do not feature very prominently in music historiography. The Austrian pianist Leopold de Meyer, who had been accorded the honorary position as Pianist to the Court in both Vienna and St Petersburg, advertised these titles prominently in the promotion of his American tour in the 1840s.Footnote 98 After a few years of service or for exceptional merit, many musicians active in Russia would also receive official decorations, most commonly in the lower ranks of the Order of St Stanislas.Footnote 99 In the history of the Empire, three musicians were awarded the highest class of this order, the Grand Cross with Star, two of whom were of non-Russian extraction: Leopold Auer and the Mariinsky conductor Eduard Nápravník.Footnote 100 Possibly overgeneralizing his own perspective, Auer suggested that musicians generally put great store on such tokens and anxiously anticipated new ones.Footnote 101 Memoirists and biographers, in any case, were often careful to mention them.Footnote 102 These decorations were not just a dead letter: for those who took permanent residence in Russia they furthered one's position on the Table of Ranks, and along with that came the prospect of ennoblement. Auer and Adolf Henselt both made it to the rank of Active Collegiate Assessor, which conferred hereditary nobility on them and gave them the title of ‘Excellency’. Such high distinctions, of course, implied a loyalty to the Russian Empire, and an indication that this was experienced as such may be found in the fact that the English Crown sought to prevent its citizens from receiving foreign decorations, which – even when awarded to musicians – had not lost their association with military orders.Footnote 103

All such reports of gifts and honours point to the continuing value of, and appreciation for, noble recognition, which added to Russia's appeal within the international market. To be sure, for some, the contacts with the Russian elite meant little more than business and calculation: the attitude of Richard Wagner, who sought out Yelena Pavlovna in 1863 hoping for ‘a grand person, who would suddenly offer me riches’, seems to come close to that;Footnote 104 at the other end of the spectrum, we find those who spent years or decades in Russian service, embraced their host country as a new home and, like Auer, became thoroughly absorbed into the world of grand-ducal soirées. For most visitors, the symbolic value of association with royalty and aristocracy remained considerable, and served as means of socially distinguishing themselves and their peers.Footnote 105 And musicians who wished to share in the lustre of the surroundings in which they had found themselves during their stay in St Petersburg or Moscow, who attributed symbolic value to a diamond ring received from the Empress or a Russian Order of St Stanislas, could not but grant these foreign elites a degree of authority.

Stately impressions

In a period when Russophobia was at times rampant, it is notable how favourably the Russian monarchy is represented in the many reports and recollections of Russia that circulated in the musical world. The Empire's social institutions did not escape critical comment by foreign musicians: in 1840, Adolphe Adam described it as a ‘country of servitude and barbarism where, nonetheless, the arts and luxury flourish’; and Louise Héritte-Viardot wrote quite extensively about matters such as police surveillance, famine, and Siberian exile in her memoirs, though these were only published posthumously in 1923.Footnote 106 Occasionally, it was intimated that there was ‘something barbaric’ about the extreme riches of the Russian upper class, but such suggestions are offset by reports about the ‘most delightful families, living in luxury, and ready to render every possible delicate attention to us’.Footnote 107 The majority of musicians not only kept their political opinions to themselves, but seemed to positively cherish the proximity to illustrious rulers and relish in the splendour of Russian high society.

When it comes to the monarchy, it is striking how often these portrayals closely match the image the Romanovs themselves would have wanted to project. To borrow Richard Wortman's term, the brilliance of the Russian court was among the ‘scenarios of power’ that served to symbolize and justify the Romanovs’ autocratic rule.Footnote 108 Many foreign musicians performed in it, and dutifully reported about it abroad.Footnote 109 Published sources, to be sure, tend to offer a more idealized picture than private correspondence, but both tend towards certain patterns. The tropes of ‘the grandiose magnificence of St Petersburg’ or ‘the so dignified and friendly affability of the imperial family’ – images that were actively cultivated under Nicholas I – seem to have been so common that a traveller like Adolphe Adam could simply reference them without much comment.Footnote 110 The recurrent appearance of the tsar in musicians’ reports and memoirs, moreover, reflected the nature of an autocracy: the sovereign, at the very least, had to pretend to be informed about and in charge of everything that occurred in the empire's high society. The picture that emerges is quite consistently that of a generous, attentive, yet supremely powerful, awe-inspiring and omnipresent figure: a magnanimous ruler or enlightened despot. Nicholas I, in particular, is typically described as a charismatic leader, ‘tall, majestic, and of much personal magnetism’.Footnote 111 Anecdotes about breaches of etiquette, as in the story about Lablache sitting at a reception in the Mikhaylovsky Palace, tend to follow a pattern that dramatizes at one stroke the social divide that separated the imperial family from mere performers and the graciousness they demonstrated by putting their guests at ease.Footnote 112 Many other stories focus on either the special favour accorded to the musicians or the way in which they held their own in the face of imperial authority, or combinations of both that would seem tailored to flatter the musician's independence and the tsar's authority simultaneously.Footnote 113 This was most transparently, and almost comically, the case with the bass Karl Formes, who shamelessly characterized the tsar as ‘the greatest autocrat’ and ‘the noblest man of his time’ (‘To know Nicholas was to love him’), and added with characteristic bravado that ‘few could endure his gaze unflinchingly; I was one of those few’.Footnote 114

Consequently, musicians’ visits also functioned as a form of public diplomacy in which autocracy presented its benevolent face.Footnote 115 Richard Stites has suggested that Russian audiences experienced the constant presence of foreign artists as a ‘reassuring force’, ‘a signifier of hopeful mutual accommodation’ in a period of tense international relations.Footnote 116 It appears that, conversely, pleasing and impressing the visiting stars served as ways for the Russian elite to communicate that positive sentiment abroad.

Conclusion

The documented experiences of nineteenth-century musical visitors to Imperial Russia open up a rich world of social relations, of wealth, imperial audiences and elegant soirées, but also of class relations, power and politics. Many aspects of musicians’ encounters with the local elites as recorded in individual biographies, letters and travel reports – the brilliance of the halls and their audiences, the social calls with the aristocracy, meeting the tsar and receiving gifts – are in fact recurring tropes in the musical discourse of the time.

Generally speaking, the dealings with Russia's elites were more than just a necessary evil. Due to the symbolic value of associating with court and aristocracy, visitors were keen to describe their glamourous surroundings, chronicle their interactions with the court, and list the gifts and honours they received. The emancipation of nineteenth-century musicians did not mean they turned their back on their old patrons and social superiors – rather, the association with monarchy and aristocracy served as means to distinguish themselves from ordinary mortals. As a result, travelling musicians circulated an image of Russia in musical discourse – an urban image of luxury, refinement and high society – that depicted Russia not so much as an ‘exotic Other’ but as a polity ‘inscribed within the system of European powers’.Footnote 117

Their representations of the imperial court and family, meanwhile, tended to reproduce the image of imposing authority and benevolence that the Romanov regime sought to project. Since the circuit of musicians who visited St Petersburg and Moscow involved a substantial cross-section of Europe's finest instrumentalists, singers and composers, these Russian relations ought to be regarded as an integral part of European musical life. And as such, they tell us how, in a changing musical world, an autocracy could remain an alluring destination.