Background

Racism is a pervasive problem in Western society, leading to physical and mental unwellness in people from racialized groups (Berger and Sarnyai, Reference Berger and Sarnyai2015; Williams, Reference Williams2020a). The pillars of the current discipline of psychology were established at the turn of the century, a time during which hierarchies of class and race were generally accepted by ruling societies as fact. It is through this lens that tenets of modern psychological thought were developed (Guthrie, Reference Guthrie2004). This past litters the present with concepts, such as biological racism, that are now known to be invalid (Degife et al., Reference Degife, Ijeli, Muhammad, Nobles and Reisman2021; Haeny et al., Reference Haeny, Holmes and Williams2021). To those who are not directly influenced by these biases, the harm that they cause to the entire profession can be difficult to perceive, and even if perceived, solutions may not be readily apparent. This paper will discuss how clinicians can recognize and embrace an anti-racism approach in clinical practice, research, and life in general.

This paper was developed from an invited address for the European ABCT (Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies) Congress in Belfast on the topic of new research on civil courage and allyship (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Faber, Nepton and Ching2022; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Sharif, Strauss, Gran-Ruaz, Bartlett and Skinta2021). As such, this paper addresses the themes reviewed in the address and is directed towards cognitive behavioural therapists and clinical researchers. The authors of this paper are three Black women who are clinicians and researchers, living and working in diverse cultural contexts. The first author is an African American clinical psychologist and research chair at a major Canadian university, where she studies mental health disparities and racialization. The second author lives in Germany and is an experienced neuroscientist and pharmaceutical professional specializing in clinical development and social justice issues. The third author is a French Canadian counselling professional and a second-generation Rwandan immigrant, who has worked extensively in the field of cross-cultural counselling supporting racialized individuals and newcomers to Canada.

Psychologists more than most recognize that racism is a fraught topic, and that just talking about these issues can make people uncomfortable, even therapists (Acosta and Ackerman-Barger, Reference Acosta and Ackerman-Barger2017; DiAngelo, Reference DiAngelo2018; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Proctor and Akondo2021; Sue et al., Reference Sue, Torino, Capodilupo, Rivera and Lin2009; Sue et al., Reference Sue, Rivera, Capodilupo, Lin and Torino2010). There are many stereotypes about different ethnic and racial groups, and in many cultures (America, Canada, Europe) we are socialized not to talk about these issues (Williams, Reference Williams2020c). Many people are afraid of being perceived as racist just by addressing the issue of racism at all. It is, however, necessary to discuss these issues to do the work of becoming culturally aware, anti-racist clinicians. To manage the anxiety evoked by this work, the principles of habituation can be applied here, as well as knowledge of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) principles (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Faber, Nepton and Ching2022). As CBT therapists and researchers, readers can tolerate the discomfort, resting comfortably in the knowledge that as they allow themselves to become more informed on the topic of race, eventually habituation will facilitate the necessary work.

With this in mind, readers should employ mindfulness if they feel triggered and be cognizant about their reactions as they digest this material. If feelings of discomfort arise surrounding challenging concepts, it may be helpful to consider the reasons for these feelings and explore the source of the discomfort. Readers should not be afraid to dig deep and ask important questions: What will it cost to change? What will it cost to stay the same? As we are all impacted by racism, what does it mean to have courage in this context, and how will this enrich the journey to become a better therapist, researcher or human being (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Faber, Nepton and Ching2022)?

Culturally informed care

Cultural competence is the ability to understand, appreciate and interact with individuals who have different cultures or belief systems. For over 50 years, this has been a key aspect of psychological thinking and practice and is an integral part of the field, increasingly recognized as an important competence that can help eliminate racial, ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in health and mental health care (DeAngelis, Reference DeAngelis2015; Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, McRae and Gordon2021).

Psychologists from the USA and Canada are required to have had training in cultural issues (Clay, Reference Clay2010; Edwards, Reference Edwards2000). However, many are now realizing that a lunchtime webinar on racism is not enough to impart the skills necessary to counsel a client on how to heal from the wounds of racial trauma. Resolving to ‘do no harm’, every clinician should take themselves to task before starting to practise therapy cross-culturally. As such, there are a few questions they can pose themselves before working with people across racial and ethnic differences (Williams, Reference Williams2019; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Reed and Aggarwal2020):

-

(1) Have you had at least a one-semester graduate course (or the equivalent) focused on multicultural counselling skills? How have you applied it in your professional work?

-

(2) Have you had skilled clinical supervision focused on issues surrounding race, ethnicity and culture? If so, how did it aid your professional work?

-

(3) Have you prepared a written cultural conceptualization about a client that was subsequently evaluated by a knowledgeable supervisor?

-

(4) Are you willing to address racial differences with clients early in therapy? Give an example of how you approach this and how it has worked.

-

(5) Do you feel competent to ask about, respond to, and support clients regarding their experiences of racism, oppression and intersectionality? Discuss any challenges and successes you had.

-

(6) Can you talk about White privilege and what it means to be White? If you identify as White, identify several areas of privilege you did not realize were a privilege of being White until you learned about White privilege.

-

(7) Can you explain the impact of racial and ethnic identity development on the therapeutic alliance?

-

(8) How many people of colour have you seen consistently for at least ten visits?

-

(9) How would you respond if your client said you were a racist? Given that this question may require more context, assume that the client says this because you are either White or not the same race as they are.

-

(10) Can you identify multiple sources of structural racism in your place of employment? (If you do not have a current place of employment, think about a past place of employment.)

Being able to answer these questions well does not guarantee cultural competence, but it is a promising start. For therapists stumped by these questions, this may be an indication that additional training or supervision is needed to better serve clients from unfamiliar cultural backgrounds.

Cultural competence is a journey, not a destination

Cultural competence is a process, and with all the changes in our society, it can be hard sometimes to know which behaviours are offensive in which contexts. Within our shifting social landscape, we see that attitudes are changing: diversity, which was once something to be ‘tolerated’, has now become a positive value. Racial groups and their definitions are changing, for example who is counted as a member of which racial group is determined by social decisions and governments (e.g. US Census Bureau) and is not a constant. Our laws are changing as well: discrimination used to be legal. There were once laws prohibiting inter-racial marriages and Jim Crow Laws in the US even dictated who could use which bathrooms. (This fight is reoccurring once again in the trans community.) How people groups designate and define themselves is changing; for example, ‘people of colour’ is acceptable usage, but ‘coloured people’ is not. Finally, the nature of how racism manifests is changing. Because it is now shameful to display overt prejudice, racism has become more covert. Learning to navigate these changes must necessarily be a process – more a journey than a destination – and as such cultural humility is an approach needed more than ever before (e.g. Owen et al., Reference Owen, Tao, Drinane, Hook, Davis and Kune2016).

Because it is harder to perceive events that one does not personally experience, it can be difficult to recognize and see acts of racism which are not directly targeted at oneself. This leads to a divided perspective along racial lines about the extent of the problem and the scope of the solutions. White people in several wealthy (American, Canadian, European) societies tend to believe that racialized groups are doing well in life, racism is declining, and they are not personally capable of racist behaviours (Sue et al., Reference Sue, Capodilupo, Torino, Bucceri, Holder and Nadal2007). People in racialized groups, on the other hand, deal with daily acts of racism (from some of those same people who do not believe they are capable of it) and thus have a quite different reality. White people tend to limit their definition of racism to blatant, intentional, overt acts, but few people who commit racist acts admit to intentionally wanting to harm others due to race (Williams, Reference Williams2020b). In modern simple conceptualizations of racism, the focus is often ‘intent’, but conscious intent is not necessary to perpetuate racism. In fact, even ‘good people’ can and do enact racism, even those who are generally against racism or have no self-awareness of any malintent.

The changing face of racism

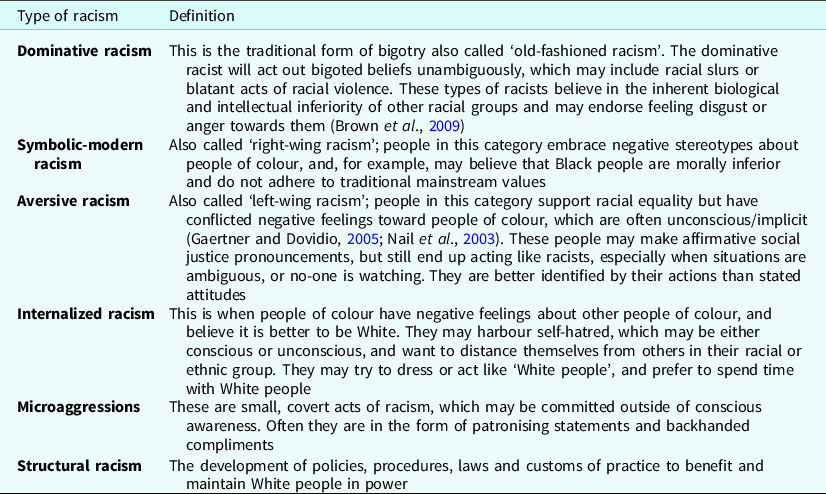

Many types of racism exist, and the form has changed over the decades. Table 1 includes the types of racism discussed here (Faber et al., Reference Faber, Strauss, Gran-Ruaz, La Torre, Bartlett, Faber, Levinson and Williams2022), but for a comprehensive treatment see Haeny and colleagues (Reference Haeny, Holmes and Williams2021).

Table 1. Types of racism

Here are examples from psychology of each of the major types of racism listed in Table 1.

Dominative racism is an overt type of racism that still exists today, even in psychology. As an example, Mankind Quarterly is an infamous peer-reviewed White supremacist social science journal that has served as a cornerstone for the dissemination of scientific racism for decades (Rosen and Lane, Reference Rosen and Lane2010; Schaffer, Reference Schaffer2007). It was first published in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1961, and then, from 1979 to 2014, by the Council for Social and Economic Studies in Washington DC. In January 2015, publication was transferred to the Ulster Institute for Social Research, in London. Although it is widely known, this racist journal is tolerated by the psychological establishment, with its papers currently indexed and available in mainstream academic databases, such as the American Psychological Association’s (APA) PsycInfo.

Modern and symbolic racism involve negative affect and prejudiced attitudes towards people of colour based on stereotypes about culture or morals (e.g. Black people prefer welfare to working, are more likely to be drug addicts, are aggressive, etc.). Modern/symbolic racists would concur and argue that people of colour receive too much special treatment compared with White people and/or other groups (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Akiyama, White, Jayaratne and Anderson2009), and would, for example, tend to oppose initiatives to recruit more faculty or graduate students of colour in a psychology program. Another example of this type of racism would be a clinician refusing evening sessions with a Black client because they believe Black people are more likely to steal or be violent at night (e.g. Kugelmass, Reference Kugelmass2016).

Aversive racism is typically enacted by people who consider themselves egalitarian and even progressive (Gaertner and Dovidio, Reference Gaertner and Dovidio2005). It is human nature to favour in-groups, but aversive racism adds an extra layer of complexity because it is socially stigmatized to overtly show that one is favouring the racial in-group. Therefore, much of racism today is the art of favouring the in-group in a covert way, then hiding both the motivation and the trail that would reveal it; for example, a White therapist who would pathologize a Black client’s reactions to a certain experience but would not pathologize a White client’s exact same reaction in a similar context (i.e. different interpretations and outcomes for patients based on the same behaviour; Londono Tobon et al., Reference Londono Tobon, Flores, Taylor, Johnson, Landeros-Weisenberger, Aboiralor, Avila-Quintero and Bloch2021; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Mccall, Spearman-Mccarthy, Rosenquist and Cortese2021).

Microaggressions are a subtle form of oppression designed to reinforce the traditional power differential between groups, whether or not this was the conscious intention of the offender (Williams, Reference Williams2020b). One example would be a psychology professor who looks at students of colour every time a question about culture comes up expecting them to provide an answer, or asking students of Asian heritage ‘where they are from’, assuming they all are immigrants (Sue et al., Reference Sue, Capodilupo, Torino, Bucceri, Holder and Nadal2007).

Internalized racism would involve a person of colour assimilating to attitudes of White supremacy and colluding to uphold Eurocentric standards (Haeny et al., Reference Haeny, Holmes and Williams2021; Pyke, Reference Pyke2010). One example would be a practicum supervisor of colour refusing to accept Black trainees into their clinical placement because they do not believe they are smart or sensitive enough to do therapy well.

Structural racism takes place at higher levels, as it is woven into organizational policies and procedures, and it also protects individuals who perpetrate racism. One example might include a psychology journal with primarily White editors and White reviewers, that disproportionately rejects papers focused on communities of colour or manuscripts from non-Western countries. Papers from White authors in Western countries with White samples tend to get preferential treatment by virtue of the fact that the editors and reviewers are from those same groups (e.g. Dupree and Krauss, Reference Dupree and Kraus2022; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Bareket-Shavit, Dollins, Goldie and Mortenson2020); or researchers from certain developing countries or lower socioeconomic status communities cannot afford the journal’s publication fees, leading to under-representation.

Racism is a European problem too

Racism has been studied extensively in the United States, but it is a problem in other Westernized countries as well, including Canada, South Africa, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom (UK). Looking at a snapshot of three major European Countries – the UK, Germany and France – gives insight into country-specific similarities in pan-European racist thought patterns.

Racism in the UK

Much has been written in the psychological literature about the US and their centuries-old legacy of racism, but that brand of racism has origins, at least in part, according to some scholars in Britain. Afua Hirsch, a Black British writer, broadcaster and best-selling author, grew up trying to make sense of the way people racialized her, as well as the injustice and unfairness in the world around her. She says that ‘today, black people in Britain are still being dehumanised by the media, disproportionately imprisoned and dying in police custody, and now also dying disproportionately of COVID-19’. She notes that ‘as long as you send all children out into the world to be actively educated into racism, taught a white supremacist version of history, literature and art, then you are setting up a future generation to perpetuate the same violence on which that system of power depends’ (Hirsch, Reference Hirsch2020). So, despite being understudied and hardly discussed, anti-Black racism creates and contributes to ongoing social problems and mental health concerns in the UK (e.g. Ghezae et al., Reference Ghezae, Adebiyi and Mustafa2022; Holttum, Reference Holttum2020).

Racism in Germany

Racism is a fixture throughout Germany, so much so that only in the last year a major street in central Berlin, which had a name that is a racial slur, was just changed to honour Black feminist and queer scholar Audre Lorde (Arndt and Ofuatey-Alazard, Reference Arndt and Ofuatey-Alazard2011; Kopp and Aikins, Reference Kopp and Aikins2020). For many years, activists have been advocating for the street to be renamed. Only recently, both in response to pressure by racialized minorities and to some surprising findings about race, Germany started to develop a National Action Plan on Racism. The introduction to this plan clearly addresses the extent of the issue, highlighting that empirical studies by the EU indicate historical and ongoing anti-minority hostility which must be condemned and addressed: ‘Germany can be found in the mid-range here. Between one-quarter and one-third of those surveyed in Germany, France, the UK and Italy had hostile attitudes …. No open and liberal democracy can accept this result’ (Federal Ministry of the Interior, 2017; p. 9). As the official policy of the German state has been not to collect data by racial category, there is currently little to no clinical data on race-based disparities in Germany; however, this is changing. The results of the 2017 Plan led to a state-sponsored census of the one million diaspora of African descent living in Germany that was completed in 2021 and confirms the persistence of anti-Black racism in Germany. The report suggests relevant research topics to steer against anti-Black hostility and discrimination (Aikins et al., Reference Aikins, Bremberger, Aikins, Gyamerah and Yıldırım-Caliman2021).

Racism in France

France also has a racism problem. In general, the French do not like to talk about racism and prefer to pivot the conversation to social class. A government spokesperson by the name of Sibeth Ndiaye writes, ‘It was when I arrived in France that I became aware of what it meant to be Black. I experienced ordinary racism. Or, more exactly ordinary racists: those who openly challenge you because you are Black and those who believe they have overcome all prejudices, but still feed them without knowing it, almost without thinking about it. But this racism, whether explicit or unspoken, was never validated by French society or institutions’ (Ndiaye, Reference Ndiaye2020). Refusing to talk about racism does not make it go away, and it does not help those who are impacted. In fact, turning a blind eye only makes it worse. Avoidance only impairs our ability to have these important conversations.

Racism in psychology

Psychology’s shameful racist past

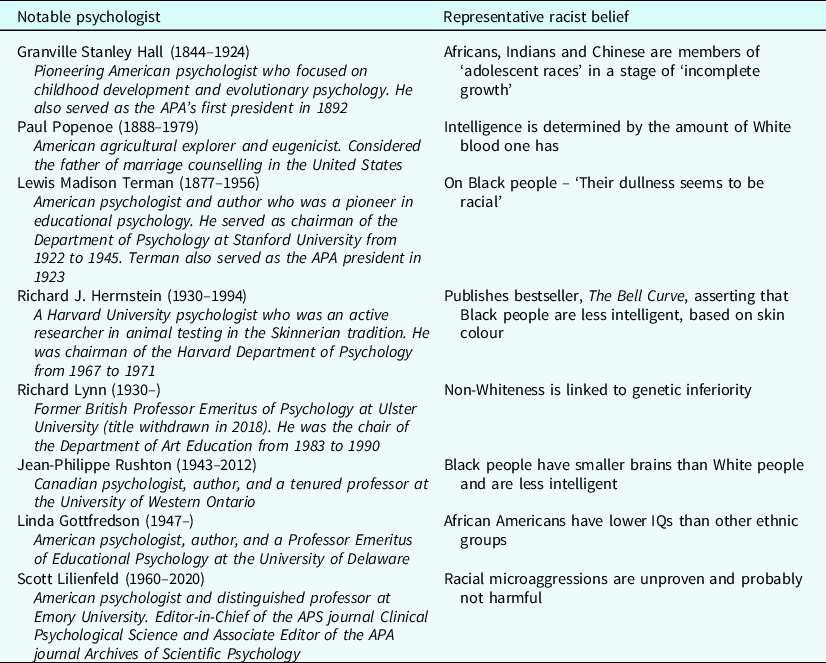

Few people are aware that the origins of the discipline of psychology were largely racist, in that many academic notables were invested in (mis)using science to prove that White people were morally and intellectually superior (Guthrie, Reference Guthrie2004). Many of these individuals were eugenicists as well; they advocated for a social agenda that included suppressing the number of children born to those they deemed less fit. These psychologists served in leadership roles such as journal editors and university faculty who were, and still are, shaping the next generations of bigots, as illustrated in Table 2 (Williams, Reference Williams2020d). As such, these racist ideas are still being taught, racist papers are still being published and cited, and racism continues to influence the discipline.

Table 2. Psychologists advancing racism

At a recent meeting, the APA Council of Representatives (2021) adopted an apology for the organization’s role – and the role of the discipline of psychology – in contributing to systemic racism. The apology acknowledges that the APA ‘failed in its role leading the discipline of psychology, was complicit in contributing to systemic inequities, and hurt many through racism, racial discrimination, and denigration of people of colour, thereby falling short on its mission to benefit society and improve lives’ (American Psychological Association, 2021). Concrete actions to remediate these harms, however, remain to be seen.

Racism in clinical care today

Racism is still happening today in clinical care, with negative outcomes for people of colour (Cénat et al., Reference Cénat, Kogan, Noorishad, Hajizadeh, Dalexis, Ndengeyingoma and Guerrier2021; Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, McRae and Gordon2021; Williams, Reference Williams2021). In a study on access to therapeutic services carried out in New York City as recently as 2016, shocking disparities were unearthed. Kugelmass (Reference Kugelmass2016) conducted a study where 320 NYC psychologists with solo practices were randomly selected from a large health insurance provider’s health maintenance organization (HMO) plan. Each received voicemail messages from a purportedly Black middle-class and purportedly White middle-class caller of the same gender, or they received a voicemail from one purportedly Black working-class and one White working-class caller of the same gender, requesting an appointment. Callers were evenly divided by race, social class and gender. Social class was constructed through the caller’s speech patterns, while caller name and accent were used to indicate race. All callers requested an appointment with a preference for weekday evenings and had the same health insurance.

Among middle-class people who contacted a therapist to schedule an appointment, 28% of White and 17% of Black callers received appointment offers, whereas appointment offer rates for both working-class therapy seekers (both races) were 8%. The study author said, ‘The fact that this study uncovers discrimination in the private mental health care marketplace is consistent with previous audit studies that have revealed discrimination in other marketplaces, such as housing and employment’ (Winerman, Reference Winerman2016). Kugelmass found that 51% of calls from middle-class White and 49% from middle-class Black callers elicited a response, compared with 45% for working-class White and 34% for working-class Black callers. The White middle-class woman was favoured for the desirable weekday evening slot, receiving an agreeable response from 16 of 80 therapists (20%). By contrast, when the Black working-class man made the same request to 80 therapists, just one therapist was willing or able to fulfil the request (1.2%). A second study with these same results came out shortly thereafter, with the telling title, ‘Is Allison more likely than Lakisha to receive a call-back from counselling professionals?’ (Shin et al., Reference Shin, Smith, Welch and Ezeofor2016).

These studies challenge the nature of intent in racism. The psychologists in this study made the intentional decision not to take on certain clients because they preferred clients they believed to be in their own group when they thought their decision was anonymous.

Approaching racism

Whiteness

It is impossible to have a meaningful discussion about racism without defining Whiteness (Haeny et al., Reference Haeny, Holmes and Williams2021). Whiteness here is defined as a socio-political in-group whose membership is defined in part by lightness of skin but also by political, social standing, and historical position. Understanding that, for the most part, people do not choose to be segregated into racial categories, society assigns in-groups and indoctrinates their correlated thought patterns to children at a young age (McGillicuddy et al., Reference McGillicuddy-De Lisi, Daly and Neal2006). White people today often do not always see how their membership in this in-group gives them increased advantageous opportunities and access to power and privilege. This makes it difficult for them to understand the experience of people of colour. However, without deconstructing Whiteness as race, privilege and social construction, we cannot start to think in ways that are explicitly anti-racist (Dlamini, Reference Dlamini2002).

Racism is learnt and we all, regardless of skin colour, learn it. Therefore, simply deciding to treat all people fairly is not anti-racist because the ingrained, pre-existing structures would continue to unjustly discriminate (i.e. racially gerrymandered voting districts). Furthermore, acting fairly towards individuals on a personal level is virtuous, but cannot undo institutional injustices such as redlining, race-norming, legacy college admissions, racially disproportionate drug sentencing, lead poisoned water, or any other historical injustice whose legacy and consequences seeps into the present day. Being anti-racist means actively combatting White supremacy by making conscious efforts and deliberate actions to dismantle historic unjust concepts, thought patterns, precepts, and structures, and provide equal opportunities for all people on both an individual and a systemic level (Haeny et al., Reference Haeny, Holmes and Williams2021).

Racism is learnt

To identify whether racial bias affects children’s reasoning about fairness and, if so, when it appears, researchers evaluated white second graders and fourth graders (de França and Monteiro, Reference de França and Monteiro2013). The researchers told two stories about three characters who produced artwork. One produced more artwork than the other two (more productive), one was poor (needy), while the third was the oldest (age-entitled). The characters’ teacher sold their artwork at a fair, resulting in an unexpected reward. The teacher gave the money to the characters and told them to divide the money among themselves in the fairest way.

With the stories, about one-third of the children saw pictures in which the oldest character was Black, one-third saw pictures with a productive Black character and one-third saw pictures with a needy Black character. In each case, the other two characters were White. The children were asked to allot the money to each of the story characters in the fairest way and explain why their choice was fair. Second graders’ responses were based on equality principles and did not vary with the character’s race. However, the fourth graders’ responses showed that children considered race. For example, they gave a greater share of the money to White needy characters than Black needy characters, while Black productive characters received greater shares than White productive characters. So, it seems clear that 9- to 10-year-old White children take race into account as they decide what is just and fair, and these considerations are based on in-group favouritism and stereotypes. These types of biases continue into adulthood. So, in summary, research shows that racism is learnt. As such, we all, regardless of race, learn about racism early in life. (For more empirical studies on how children learn social rules about bystanderism and discriminatory behaviour, also see McGillicuddy et al., Reference McGillicuddy-De Lisi, Daly and Neal2006; Staub, Reference Staub2019.)

What does it mean to be anti-racist?

Simply deciding to treat all people fairly is not anti-racist – this is just being a passive bystander, subject to learnt biases (Faber et al., Reference Faber, Strauss, Gran-Ruaz, La Torre, Bartlett, Faber, Levinson and Williams2022). There are several reasons for this. First, as all humans have in-group preferences learnt from childhood, which runs alongside the social stigma of not overly showing that one’s own in-group is preferred, without careful self-analysis it can be difficult to see where and how one’s own biases are functioning (McGillicuddy et al., Reference McGillicuddy-De Lisi, Daly and Neal2006; Hansen, Reference Hansen2017). Secondly, just being aware about one’s own in-group biases does not make them magically disappear. Finally, as we are all living in the legacy of an unjust and racially biased system, without deliberate action, these injustices of the past are perpetuated into the present and continue to occur (Sue, Reference Sue2017).

Being anti-racist means actively combatting systemic in-group preferences, and structural injustices, wherever they may appear. This means working to counter racial prejudice, systemic racism, and the oppression of racialized groups. This includes conscious efforts and deliberate actions to provide equal opportunities for all people on both an individual and a systemic level. It is necessary to centre and prioritize the voices of people who are racialized. It requires a life-time philosophy of humility, acknowledging personal privileges, confronting acts as well as systems of racial discrimination, and working to change personal racial biases (Donovan et al., Reference Donovan, Semmens, Keck, Brimhall, Busch, Weindling, Duncan, Stuhlsatz, Bracey, Bloom, Kowalski and Salazar2019; Spanierman and Smith, Reference Spanierman and Smith2017).

Allyship

Allies are people who recognize the unearned privilege they receive from society’s patterns of injustice and the harm it inflicts today, and take responsibility for changing these patterns regardless of any negative consequences for themselves personally (Williams and Sharif, Reference Williams and Sharif2021; M.T. Williams et al., in press). Allies include White people who work to end racism (anti-racism allies), men who work to end sexism, heterosexual people who work to end heterosexism/homophobia, and cis-gender people who work to end cis-centrism/transphobia (Williams and Sharif, Reference Williams and Sharif2021). Today, many White people are proclaiming their racial justice allyship, with hashtags and lawn signs that say, ‘Black Lives Matter’. Unfortunately, observation and research indicate that racial justice allies are actually quite uncommon (Williams and Sharif, Reference Williams and Sharif2021).

We carried out a study to determine the degree to which White individuals would behave in an allied manner when provided the opportunity to do so. White participants participated in a laboratory behavioural task where they engaged in three 5-minute discussions with another White participant (a confederate) about racially charged news stories in the United States while knowingly being watched by a Black research assistant via live recording. Stories represented different forms of racism towards Black people: the removal of a Confederate monument; the killing of an unarmed Black male college student by police after a car accident; and a fraternity party where members had a party dressed as Black stereotypes. Coders were asked to rate how they believed a person of colour would feel interacting with that participant using a 4-point Likert scale: 0 (absence of any supportive comments) to 3 (very explicit, unwavering support for non-racist and equity values and behaviour).

We initially decided that those defined as ‘allies’ would score a 3 on all three scenarios, but no participants met that bar. So, we lowered it to a score of 2 or higher on all three scenarios. Results showed that when using a mean cut-off score of 2 as an indicator of allyship for each laboratory scenario (consistent support throughout the interaction), only 6.4% of participants met these criteria (on average). Furthermore, only 3.2% of the participants were allies in all three scenarios (9.7% were allies in two scenarios, and 16.1% were allies in one scenario). The results were painful but important, in that we saw first-hand that White people consistently showed a lack of allyship towards Black people (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Sharif, Strauss, Gran-Ruaz, Bartlett and Skinta2021); and this study was not conducted in the Deep South, but rather the University of Washington in Seattle – a place that prides itself on inclusivity and progressive practices.

Being a racial justice ally

Racial justice allies display behaviours such as identifying and decentring Whiteness, empowering people of colour, and confronting uncomfortable or shameful race-based topics through ongoing education, and engaging in reciprocal vulnerability and accountability (Printz Pereira and George, Reference Printz Pereira and George2020; Spanierman and Smith, Reference Spanierman and Smith2017).

Although we often talk about the importance of White allies, anyone can be an ally, as racialization is hierarchical based on skin colour and presumed heritage. For example, an East Asian person can be a racial justice ally toward a Black person, if the East Asian person has more privilege in a specific environment. (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Faber, Nepton and Ching2022).

Although many people aspire to be racial justice allies, they find they fall short when the time comes to act as an ally. Several factors lead to this cognitive conundrum. Most people want to avoid thinking about race because it stirs up uncomfortable feelings. Furthermore, they may experience fear and anxiety that if they stand up for racial justice, they will face disapproval by others who do not support racial justice. Or they may worry that they are doing it ‘wrong’. As such, racial justice allyship can be a difficult and painful process.

It can be helpful to highlight some characteristics and actions that can help orient would-be allies towards more their desired allyship behaviours, as opposed to what we sometimes call ‘saviourship’ behaviour. Examples can help as people often confuse being a White ally with being a White Saviour. Saviours want to help because it makes them look good or feel good, but are not really interested in fairness or power sharing. Neither racial justice allyship nor problematic ‘saviour behaviours’ are limited to White people; nonetheless, the ‘White Saviour’ is a common theme in our culture, as seen in popular feel-good movies (e.g. The Help, Dances with Wolves, The Blind Side, Avatar, Hidden Figures, etc.). There are specific characteristics that differentiate a racial justice ally from a racial justice saviour in terms of motivation, expectations, connection and accountability that will be briefly reviewed from Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Sharif, Strauss, Gran-Ruaz, Bartlett and Skinta2021).

Motivation

The racial justice ally is motivated by values surrounding equity, inclusion and diversity, and acts out of genuine concern for the well-being of people of colour in their lives. Conversely, saviours are seeking reputational benefits, personal glorification, or are motivated by White guilt, to feel like a ‘good person’ or to say they have ‘done their part’. An example of an action motivated by saviourship would be attending a social justice event and posting selfies on social media to broadcast one’s ‘allyship’.

Action

A racial justice ally would work to transform White-dominated systems to be equitable, fair and just. They would maintain cultural humility, freely apologize for mis-steps, and step back and create opportunities for people of colour to be centred. Conversely, a saviour would help people of colour navigate a system (rather than confront the system) of White dominance, broadcast allyship behaviours and sentiments without accepting criticism, centre themselves and overstate their own relevance.

Moreover, a racial justice ally understands that White-dominated systems must be transformed to be equitable, fair and just, and is willing to take up the necessary work to start this process. For example, if an ally notices that an Indigenous patient is being treated badly by clinic staff, the ally will not only insist on better treatment, but work to ensure systems are implemented to prevent this from happening in the future – for example, implementing patient satisfaction questionnaires to ensure people of all racial groups are having a good experience. An ally furthermore maintains cultural humility and freely apologizes for any mis-steps, which are expected. An ally does not need to be the centre of attention.

Finally, a racial justice ally works to understand the needs of the group with which they hope to ally themselves and hold themselves accountable to those groups. In contrast, a racial justice saviour will pursue actions to obtain reputational benefits or personal glorification. They are motivated by guilt to feel like a ‘good person’ or to be assured that they have ‘done their part’.

Expectations

An ally will anticipate that anti-racism work is an ongoing effort to dismantle individual and institutional beliefs, practices and polices. They expect that learning about diversity issues will be a continual process of hard work and self-reflection, understanding they will at times receive disapproval and punishment from dominant in-group members. For example, an ally will freely offer support to a colleague of colour who may be struggling with racism without expecting acknowledgement or thanks.

On the other hand, saviours expect acknowledgement, credit and/or glory for their efforts. They label themselves ‘allies’ and expect others to agree. They also expect people of colour to be grateful for their good intentions, even if they accidentally cause harm. For example, they would expect praise and support for offering discounted therapy for clients of colour.

Connection

A racial justice ally builds meaningful relationships with members of the groups with which they aspire to ally themselves. As such, they will have several close friends of colour to which they would reach out to if in need or for mentorship. However, saviours tend to maintain hierarchical or distant relationships with members of the groups with which they wish to ally themselves, and, conspicuously, these people lack close friends of colour (Aberson et al., Reference Aberson, Shoemaker and Tomolillo2004; Cox et al., Reference Cox, Navarro-Rivera and Jones2016).

In a clinical context, an ally would check in with therapy clients of colour when something racist has happened in the media, and show care and support, whereas a saviour might pathologize a racialized client over an emotional reaction to racism in the media, saying ‘be calm and rational’ instead of justifiably distressed (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Sharif, Strauss, Gran-Ruaz, Bartlett and Skinta2021). One example of this lack of connection would be a group of White therapists trying to attract Black clientele by putting the phrase ‘Black Lives Matter’ on their website, despite not having any racial diversity among their clinical staff.

Accountability

In terms of accountability, allies work to understand the needs of the groups with which they hope to ally themselves and hold themselves accountable to those groups, whereas saviours do not hold themselves accountable to the groups with which they claim to ally themselves, but only to their own goals. An example of allyship would be asking people of colour (colleagues, community stakeholders, friends) for constructive criticism on a regular basis regarding one’s own anti-racism efforts.

Addressing subtle racism and microaggressions

In today’s society, rather than overt or explicit expressions of dislike toward out-groups, much racism is communicated through microaggressions. Importantly, these actions allow for an amount of plausible deniability, as explicit and overt racism is socially no longer acceptable and microaggressions are coded language and therefore somewhat hidden. Microaggressions are as such not simply cultural mis-steps or racial faux pas, but a form of oppression designed to reinforce the traditional power differential between groups in a covert way, whether or not this was the conscious intention of the offender (Williams, Reference Williams2020b; Williams, Reference Williams2021). They have been organized into four major categories by Spanierman and colleagues (Reference Spanierman, Clark and Kim2021), based on the actions of the person committing the microaggression:

-

(1) Pathologizing differences;

-

(2) Denigrating and pigeonholing;

-

(3) Excluding or rendering invisible;

-

(4) Perpetuating colour-blind attitudes.

When it comes to microaggressions, there are multiple steps that can be taken to expose and disarm these subtle acts of racism, as described by Sue and colleagues (Reference Sue, Alsaidi, Awad, Glaeser, Calle and Mendez2019). As microaggressions often fly under the radar, the first step is to make the invisible visible by making the meta-communication explicit. This draws attention to the underlying pathological stereotype and also informs the offender that the statements are inappropriate. Secondly, expressing disagreement in some way using non-verbal communication or interrupting and directing can also help to challenge the microaggression. Thirdly, educating the offender is another way to disarm microaggressions because these acts are often rooted in faulty information (Williams, Reference Williams2020c).

Although microaggressions should be challenged, when possible, it is not always safe for racialized people to address a microaggression in the moment, and here is where the racial justice ally can step in to really make a difference (Williams, Reference Williams2020c; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Faber, Nepton and Ching2022). As members of more privileged groups, the words of the racial justice ally carry more weight and they are less likely to experience negative consequences for speaking out (Sue et al., Reference Sue, Alsaidi, Awad, Glaeser, Calle and Mendez2019).

Practical methods for dealing with microaggressions

As most racialized people experience microaggressions regularly, therapists should anticipate that microaggressions will be a topic of therapy occasionally, if not often. There are three main ways microaggressions appear in clinical care:

-

(1) A client of colour wants to discuss microaggressions experienced at work or in daily life;

-

(2) A client makes a microaggressive statement in therapy;

-

(3) The therapist makes a microaggressive statement in therapy.

Each of these will be briefly addressed.

Client wants to discuss microaggressions experienced at work or in daily life

In the same way racial microaggressions happen in everyday life, they are also observed in clinical care. Because of in-group solidarity, and the implication that negative actions of any member of one’s in-group can be imputed to oneself (guilt by association), the typical reaction to hearing about an act of injustice or a microaggression committed by someone in one’s in-group is to try to excuse it or explain it away. This is a normal human reaction. In addition, because the social stigma of being labelled as a racist is so high, when clients of colour report on injustices experienced from White people, a White therapist’s impulse to believe that it may not be true is that much higher. To be effective, the therapist must decouple any feelings of guilt-by-association when listening to a person of colour testifying about racial injustice, even if they feel that the client is including them in the group of oppressors (which, because the client is hurting, they may be doing!). This is not easy work. Key points include:

-

(1) Do not question if it was really a racial microaggression;

-

(2) Respond with empathy, validation and support;

-

(3) After validating, problem-solve around the issue.

Clinicians can reflect on the different ways they assess and respond to the impact of racism in clients to help them move forward. Sometimes, the problems are much more serious than an occasional microaggression, and it can help to use validated measures to assess the problem, and include race, ethnicity and culture in the case formulation (Graham-LoPresti et al., Reference Graham-LoPresti, Williams, Rosen, Williams, Rosen and Kanter2019). It is critical to recognize the psychopathological impact of racism in all its forms, address and treat racial trauma, support a positive and strong ethnic identity, and help clients build skills to respond to racism.

Client makes a microaggressive statement in therapy

Microaggressions of this sort can happen in many ways. Clients may commit a microaggression (1) against a racialized therapist directly attacking the therapist’s identity, (2) against a racialized group in the presence of a therapist from a different racial group, or (3) against a racialized group or person in the presence of a White therapist, expecting in-group loyalty.

Regardless of the identity of the therapist, it is important to teach clients that microaggressions are hurtful acts of racism. If they are committing microaggressions in session with the therapists, they are doing them outside of therapy too, causing hurt towards people of colour and offending White people who care about people of colour.

Therapist makes a microaggressive statement in therapy

Research shows that it is very common for therapists to commit microaggressions towards their marginalized clients (Constantine, Reference Constantine2007; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Tao, Imel, Wampold and Rodolfa2014). If a therapist becomes aware that they have committed a microaggression, a repair should be initiated (this process is explained in detail in Williams, Reference Williams2020c). It is not always immediately evident for many therapists that they may have committed a microaggression. In a clinical setting, it is crucial to invite clients (and others) to carry out a ‘call out’ of the offending therapist. It is the clinician’s responsibility to create a safe space and make room for an open dialogue. For example, people of colour may be reluctant to point out problems for fear of punishing reactions. A good therapist will pre-empt the problem and then recognize power imbalances and finally invite others to comment if this happens.

In the event that a therapist is called out, here are some steps that can be taken to solve the problem (Williams, Reference Williams2020c). The therapist should:

-

(1) Not become defensive;

-

(2) Demonstrate empathy for the client;

-

(3) Ask why the called-out behaviour was racist and listen;

-

(4) Validate the perspective of the individual making the call out;

-

(5) Acknowledge personal biases and blind spots;

-

(6) Clarify any misinterpreted remarks;

-

(7) Make it right.

Building ethnic identity

Supportive statements about your client’s ethnic group are an important way to help build resilience against racism, but are sadly under-utilized. In our own research focused on understanding tendencies of White students to commit microaggressions, in our battery of questions, we included behaviours that were either microaggressive, non-microaggressive/neutral, and supportive (Michaels et al., Reference Michaels, Gallagher, Crawford, Kanter and Williams2018). In examining our data, we were surprised to discover that many of the items considered supportive by our lab, diversity experts, and Black students alike were not regarded similarly by White respondents. Several items that would have made Black students feel supported were very unlikely for White students to do or say (e.g. ‘Say that you object to the song [containing the n-word] because it bothers your [Black] friend’ or asking ‘What’s it like for Black students in the law school?’). We see the same in therapeutic relationships as well. Therapists are often so afraid of making a mistake they say nothing at all (Constantine, Reference Constantine2007).

Often, clients have internalized many negative ideas about themselves and their group that manifests as psychopathology originating from an overwhelmingly toxic social environment. In these cases, detoxifying treatment is needed in the therapeutic process. This may include frequent positive affirming of the client and their ethnic group to provide a counter-perspective to the harmful negativity they experienced. It is important to acknowledge that these affirming comments should be genuine and not based on stereotypes (Williams, Reference Williams2020c). For example, a therapist might say, ‘As a people, African Americans have exhibited an unprecedented amount of grace, in spite of living in a society which has heaped abuses upon them’; or ‘Like a diamond, African Americans have endured the immense pressures of American society and have not only survived but they shine. They should be honoured for their contribution as a people, in making America a better place’.

What can we do about racism?

As psychologists, we look to our field and our science to help answer questions, supported by modern clinical psychological science (Kanter and Rosen, Reference Kanter and Rosen2016; Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Kanter, Villatte, Skinta, Loudon, Williams, Rosen and Kanter2019). Our understanding of racism today is very different than racism of the past. The way we talk about these issues is evolving, and we must learn the new language around racism. The next step is to get better at accepting, rather than avoiding, difficult feelings surrounding race. As we notice these feelings, we should become curious about the stereotypes and biases that arise within us and learn how to deal with them. The final step is to commit to get active and be part of the solution.

An important part of this is to take risks to forge real relationships and connect with diverse others. People from other racial and ethnic groups can be invaluable for learning about others, developing empathy, and improving one’s clinical practice (Okech and Champe, Reference Okech and Champe2008). That being said, these must be reciprocal relationships. It is important to ensure these relationships are equitable, without expectations that the racialized person will serve the other as an educator.

Using personal power for good and reclaiming individual racial identity

People who aspire to make a difference feel discouraged that they are saddled with a racial label that they may not want. For members of dominant groups, the good news is that this power can be used for good and the unwanted racial identity can be re-purposed. Being labelled with a society imposed racial moniker (i.e. White, Asian, Black), which may have nothing to do with the way in which an individual understands their own identity, can elicit feelings of complicity or victimization that can be accompanied by shame, but racial identity is not destiny. To be a White ally is to know, accept and understand that White identity is not necessarily a chosen identity, but nonetheless gives those who possess it, special power in many societies to bring attention, intervention and justice to situations where a racialized person would not be able to act.

For those who are racialized in Western Society, that is also something not chosen and usually indelible, but life-long experience with injustice and suffering bestows eyes to see it and the empathy to make positive changes that a White person may not immediately notice.

Finally, for those who may look like a White person but identify as a racialized or as otherwise minoritized person, this grants them the unique position of being an unseen witness in the camps of the unjust and to hear and see things that a clearly racialized person would not know or hear, and then make a positive change either upfront or behind the scenes (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Faber, Nepton and Ching2022).

Combatting systems of oppression in our discipline

There are invisible systems of dominance all around which children notice, but many adults have forgotten how to see (McGillacuddy et al., Reference McGillicuddy-De Lisi, Daly and Neal2006; Staub, 2019). Anyone can open their mind to relearn to see these systems if they choose to do so (Donovan et al., Reference Donovan, Semmens, Keck, Brimhall, Busch, Weindling, Duncan, Stuhlsatz, Bracey, Bloom, Kowalski and Salazar2019). There is a need to recognize racism as a societal psychopathology and thereby reject systemic in-group privilege. This means actively looking for ways to give people of colour, or other out-groups, an equal voice in forums (including powerful positions in our organizations, such key decision-makers and on the board of directors). Allies must speak out when they observe racism, not expecting any rewards for doing the right thing, and embrace cultural humility.

Transforming our discipline: whose responsibility is it?

In psychology, specifically, we need to transform our discipline by addressing four specific problems:

Problem 1

We are not producing enough psychologists of colour (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Lee, Hogstrom and Williams2017). The supply of psychologists is insufficient to address the unmet need for mental health services. In 2019, the US workforce consisted of 83% White and 17% racial/ethnic minority psychologists (American Psychological Association, 2020), but only 60.1% of the US population is non-Hispanic White. APA projections indicate a large demand for psychologists of colour between 2015 and 2030, given the increase of 30% within the Hispanic population and 11% within the Black American population (American Psychological Association, 2020). According to a 2013 study by the Health & Social Care Information Centre, in the UK, Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) people account for only 9.6% of qualified clinical psychologists in England and Wales, compared with 13% of the population (Office of National Statistics, 2018). Canada does not collect information on the race or ethnicity of psychologists, but in their 2018 response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, the Canadian Psychological Association (CPA) estimated that out of approximately 19,500 psychologists in Canada there are fewer than 12 Indigenous practising or teaching psychologists (Canadian Psychological Association & Psychology Foundation of Canada, 2018), accounting for 0.06% of all psychologists in Canada. This is despite Indigenous peoples accounting for approximately 5% of the population (Statistics Canada, 2017), meaning that they are shockingly about 100 times under-represented in the field of psychology.

Furthermore, about 91.5% of the members of the British Psychological Society are White (Bullen and Hacker Hughes, Reference Bullen and Hacker Hughes2016). Changing this requires accepting percentually more people of colour into doctoral programs and mentoring them through to degrees and tenure track positions. In 2016, a greater percentage of White-identifying applicants were accepted to clinical doctoral programs in comparison with Asian and Black applicants (4% of the 6% Asian British and 2% of the 4% Black British, compared with 91% of the 84% of White groups were admitted). In addition to this bottleneck in acceptance, some of the additional difficulties that may inhibit BAME students from pursuing further education in the field include inadequate visibility of BAME professionals in the field, lack of exposure to cultural issues in psychology, experiences of racism, microaggressions, and biases in both the profession and academic level.

Problem 2

Psychologists of colour experience marginalization and discrimination within their own ranks (e.g. Delapp and Williams, Reference Delapp and Williams2015). About 78% of faculty in accredited doctoral psychology programs are White (Smith, Reference Smith2015) and nearly 70% of individuals being awarded doctoral degrees are White US citizens/permanent residents (Kang, Reference Kang2020). Faculty of colour are over-represented in lower ranks (i.e. assistant professor), but under-represented as full professors, which limits power and influence as leaders in their institutions (U.S. Department of Education, 2020). In Canada, there is a lack of diversity in senior leadership positions in academia, especially of racialized people (Universities Canada, 2019).

Problem 3

Diversity education of graduate students and mental health clinicians is mostly inadequate (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Lee, Hogstrom and Williams2017). Although most clinician training programs provide some material on multicultural counselling, many do not, and most older psychologists never received any training at all. To address these concerns, there is a growing call to expand cultural competence education for psychologists and psychology trainees. However, education alone is not sufficient, as direct clinical experiences and supervision related to working with diverse clients is also needed to facilitate cultural competence. We cannot evaluate cultural competence on clinician impressions alone, as individuals tend to over-estimate their level of cultural competence, due in part to social desirability (Larson and Bradshaw, Reference Larson and Bradshaw2017). Furthermore, cultural safety rather than cultural competency may be more salient, as racialization creates its own aversive power dynamic (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Jones, Tipene-Leach, Walker, Loring, Paine and Reid2019). There is a pressing need to integrate cultural competency and awareness into both training and supervision models (e.g. Williams and La Torre, Reference Williams, La Torre, Storch, Abramowitz and McKay2022).

Recommendations include the implementation of ongoing anti-oppression training for all clinicians/staff/students [provided by BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of colour) individuals who are appropriately compensated], financial stipends or professional days to support didactic and experiential training related to diversity and equity, and regular discussion of diversity issues in supervision and consultation groups (Students for Systemic Transformation and Equity in Psychology, 2020).

Problem 4

We are paralysed by anxiety and avoidance that prevents change. At an individual level, we are afraid to address our own issues (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Williams, Wetterneck, Kanter and Tsai2015). Many therapists are unprepared to address cultural issues due to inadequate cultural education and social taboos surrounding racism, discrimination and White privilege (Neville et al., Reference Neville, Worthington, Spanierman, Ponterotto, Casas, Suzuki and Alexander2001; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Proctor and Akondo2021; Terwilliger et al., Reference Terwilliger, Bach, Bryan, Williams and Di Fabio2013). Civil courage is needed to implement anti-racist solutions, as backlash in inevitable (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Faber, Nepton and Ching2022). Civil courage, unlike other forms of courage, is characterized by a passion for social change. Individuals who exhibit civil courage are aware of the negative consequences and social ramifications of their actions but choose to persist based on a moral imperative.

There is much to be done in the field of psychology to reform the profession to be capable of providing culturally competent therapy to minoritized persons in need of services. We need to diversify our workplaces, social networks, fields and organizations. Psychologists of colour may have different priorities than White psychologists but there is room for everyone at the table. All of our voices are needed.

Conclusion

Being anti-racist in the 21st century can be complicated and confusing as terminology, behaviours and expectations shift with the social forces of the times. Anti-racist clinicians must work towards cultural competence, which is an ongoing process. To be truly anti-racist, one needs to commit to being an ally for racial justice and not a saviour. This includes acknowledging personal biases and apologizing if called out, making supportive statements about your client’s culture, and engaging in ongoing personal work around racial issues. Additionally, as an anti-racist therapist, you should cultivate close meaningful relationships with people from different ethnic and racial groups, all the while educating yourself and engaging in ongoing learning. Ultimately, the anti-racist clinician will achieve a level of competency that will promote safety and prevent harm coming to those they desire to help, and they will be an active force in bringing change to those systems that propagate emotional harm in the form of racism.

We recognize that becoming an anti-racist clinician is no small feat, and many of the concepts and actions described herein were only addressed at surface-level. We hope readers desiring more information will avail themselves of the material in the ‘Further reading’ section for more information and step-by-step instructions on how to accomplish these challenging but worthwhile goals.

Key practice points

-

(1) Anti-racist therapists work towards cultural competence, which is an ongoing process and requires humility.

-

(2) Being a racial justice ally is difficult but important, and includes acknowledging and working on personal biases.

-

(3) Therapists must support their racialized clients’ ethnic and racial identities.

-

(4) Therapists should cultivate close meaningful relationships with people from different ethnic and racial groups to inform their practice with diverse clients.

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

This paper was originally presented as a keynote at the 50th European ABCT conference in Belfast, UK. The authors would like to acknowledge Manzar Zare for her assistance with proofreading.

Author contributions

Monnica Williams: Conceptualization (lead), Funding acquisition (lead), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Resources (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Sonya Faber: Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (equal); Caroline Duniya: Validation (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs Program, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant number 950-232127 (PI M.T. Williams).

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.