Introduction

The Global Compacts on Migration and Refugees (2018) established comprehensive standards for facilitating safe and orderly migration. However, states have implemented the principles selectively. The gap between intentions for multilateral governance and implementation practices is especially visible in the field of transit migration, a regional phenomenon where interventions from state and international institutions are often ineffective. Here the categories of migrants are fluid between refugees and regular and irregular migrants. Governance also takes place informally. It is problematic that we still know little about how formal and informal interactions among actors contribute to transit migration governance. How can we better understand such dynamics beyond the role of institutions? How can we discern and compare such dynamics in different world regions?

This article advances a relational approach to polycentric governance of transit migration, suited for regional analysis. There is much to be gained in the understanding the governance of migratory and refugee transit flows, if we switch from an analytical perspective focused on individual regimes to a polycentric perspective that considers the social interactions between actors in a complex governance landscape. While scholarship on migration regime complexes emphasises the role of intersecting formal institutions, I argue that at the core of such governance are polycentric social relations among governmental, non-governmental, supranational, and non-state actors, as well as sending and destination states, forming regional governance architectures. These architectures include informality and do not necessarily lead to the emergence of rules-based institutions, as governance scholarship often thinks. The resulting mixture is power-laden, based on mechanisms of cooperation, conditionality, containment, contestation, and coercion and others, linking different actors in regionally specific ways. When repeated, such relationships become durable structures shaping actors’ behaviour.

This article seeks to categorise such power-laden relationships in the Balkans and the Middle East, two regions in the European neighbourhood with abundant transit migration. This piece does not feature an explanatory theory about transit migration governance, but a novel lens into polycentric governance architectures formed regionally on the basis of social relations. These are a solid set of formal and informal rules emerging from interactions of multiple actors at different scales. Reproduced relational dynamics create specific conditions that allow actors to respond to transit migration in a particular region in specific ways. Thereby this article advances the need to look at transit migration governance from a polycentric perspective in the first place, and to consider specifically a new relational way of thinking about polycentricity where the analysis focuses on the power-laden social relationships that bind different actors when governing.

The article continues with a review of three scholarly streams: transit migration, international migration regimes, and regional migration governance. I further introduce my relational approach to polycentric governance of transit migration and map out the mechanisms constituting each relational link. I bring comparative evidence from the Balkans and the Middle East. I conclude by discussing the importance of analysing polycentric governance and informality in international migration politics.

Transit migration and transit states

Transit migration is broadly defined as ‘migrants having the intention to move onwards to a third country’.Footnote 1 Transit states are those that host transit migration. Transit migration narrowly concerns persons holding a transit visa but is broader in practice.Footnote 2 A record 1.3 million refugees applied for asylum in the European Union (EU) in 2015, nearly double 1992's high of 700,000.Footnote 3 Some arrive as refugees but do not apply for asylum under the EU Dublin regulations in the first receiving state and continue on to other destinations. Refugees often become part of irregular migration,Footnote 4 smuggled on dangerous journeys and vulnerable to exploitation and death in transit.Footnote 5 Some labour migrants also have visas but overstay their time and become irregular migrants, seeking accommodation elsewhere.

Some become trapped in transit states. Bottlenecks, detention centres, logistical problems, changing asylum systems, tightened border controls, hostile environments, and lack of economic, social, and legal opportunities can prevent refugees from moving on, and turn them into ‘stranded migrants’.Footnote 6 Postcommunist countries of Eastern Europe – with little immigration experience – host refugees and irregular migrants but resist accommodating them, creating incentives for further transit. Opposition to new migration flows has engulfed Italy, Spain, and Greece, seeking for decades to contain irregular migration. Libya, Morocco, and Egypt have served as transit countries with conflict-generated migration from Africa, as has Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan for those fleeing the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. Transit states may try to contain, confine, and disperse irregular migration,Footnote 7 but can also informally let migrants move on to other places.Footnote 8

A rapidly growing scholarship sheds light on transit migration in the European neighbourhood. It is associated with EU's policy of ‘externalisation’, seeking to manage migration before it reaches its borders.Footnote 9 The EU uses economic and political conditionality, linking migration control in transit states with economic development, as in Morocco, Libya, and elsewhere in North Africa,Footnote 10 in addition to prospects for EU integration regarding TurkeyFootnote 11 and the Western Balkans.Footnote 12 Morocco and Libya, exposed to forced migration from sub-Saharan Africa, and others like Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon exposed to flows from the Middle East, manage migration as both sending and transit states.Footnote 13 Besides a controversial 2016 EU-Turkey deal to stop irregular migration towards Europe, similar EU ‘migration compacts’ have also been signed with Jordan, Lebanon, and Niger.

Critical analyses of border regimes highlight the Eurocentric and securitised connotations of the term ‘transit migration’.Footnote 14 It has become a ‘convenient euphemism for subjects that are potentially politically delicate’Footnote 15 and perceived as a threat.Footnote 16 Multiple actors connect for ‘polyvocal’ interventions in managing irregular flows, often based on securitised discourses or everyday practices.Footnote 17 Aside from EU institutions and transit states, this includes non-state actors, such as NGOs, as well as EU citizens who perform ‘border work’, which they do through ‘envisioning, constructing, maintaining and erasing borders’Footnote 18 and creating ‘vernacular’ imaginaries of border securityFootnote 19 in their everyday lives.Footnote 20 In addition, surveillance technologies are deployed at borders and via ‘remote control’, reaching deep into states’ territories through a system of passports, visas, and pre-screening among passenger carriers.Footnote 21 Critical studies further highlight that migrants and refugees are not passive recipients of these policies, but actively voice, contest, and seek to participate in creating more just terms of their governance.Footnote 22

This article addresses two major lacunae in this scholarship. First, although various actors are implicated in transit migration governance, emphasis still lies with state and international organisations. My piece aims to shift analytical attention away from institutional and other actors and toward their social relations, including informal interactions. Second, although governance mechanisms, such as control, containment, and dispersal, are identified,Footnote 23 scholarship discusses their contextual implications separately, with evidence quite often from transit countries like Italy, Spain, Greece, Malta, Morocco, Libya, Turkey, and Lebanon. Analysis does not focus on the power-laden mechanisms underpinning the relationships among relevant actors in a particular region. Demonstrating how such relational governance architectures are built is a major contribution of this article.

Migration regimes and regional migration governance

Scholarship on international migration regimes has sought to account for complexity in migration governance. ‘Regime’ is often defined as the ‘principles, norms and decision-making procedures around which actor expectations converge in a given issue area’.Footnote 24 The emphasis has been on how international legislative and policy frameworks of nation-states intersect in complementary or substitutive ways. Historically based on governing refugees and labour and postcolonial migration,Footnote 25 regimes have introduced migration controls.Footnote 26 The refugee regime has been clearly based on the 1951 Convention and its 1967 Protocol, and the responsibility of The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) to govern it, yet matters are more complex.Footnote 27 As Gil Loescher, Alexander Betts, and James Milner explain, the UNHCR argues that ‘refugees are not migrants’, and by extension transit migrants are not relevant here. However, in crossing borders refugees depend on multiple policies during their transit, including those of the International Organization of Migration (IOM), travel and visa regimes, and regimes related to internally displaced persons (IDPs), human rights, and labour migration.Footnote 28 Such regime complexity has been theorised upon in the IR literature more broadly,Footnote 29 and in migration governance specifically,Footnote 30 by putting emphasis on interactions between institutions, not on social relations. ‘Doubters’ in scholarship on migration regimes emphasise a top-down centralised understanding of institutions, while ‘discoverers’ focus on place-based contextual dynamics generating governance effects bottom-up.Footnote 31

These theories capture well how regimes intersect and overlap in governing migration, while authorities expand or contract their mandates.Footnote 32 However, they are less attentive to informality operating alongside formal institutions, and to the social relationships among those involved. This is where a polycentrism perspective becomes helpful, as it shifts focus away from legal and policy frameworks to interactions among various ‘centres’ that find ways to self-regulate while operating at different scales. This article further emphasises the need to look into the power-laden social relationships that bind such ‘centres’ durably and form governance architectures that enable or constraining behaviours.

Finally, building on IR theories on regional governance,Footnote 33 migration scholars have demonstrated that states and international organisations establish interaction patterns in different world regions. The notion of a region gained traction after the Cold War as a meso-level field of reference,Footnote 34 larger than the national but smaller than the international or global level.Footnote 35 Regions can be considered geospatially, constructed discursively, or mapped onto a specific institutional space. I consider regions as geospatial areas characterised by a specific set of relationships between political and social actors involved in governing migration.

European migration governance has taken centre stage so far in these studies. The focus has been on the right to free movement for EU citizens, attempts to establish common migration and asylum policies, and cooperation to affect migration in other countries and regions.Footnote 36 A multilevel governance perspective is often put forward to account for such a complex yet relatively well-regulated institutional and policy environment.Footnote 37 Knowledge about governing mobility in other regions is less advanced. Governance is found to occur ‘in different fora, with overlapping but incongruent memberships’,Footnote 38 and discussed primarily from an institutional perspective. This includes recent work on the Economic Community of West African States, a Mercosur Residence Agreement in Latin America, the Eurasian Economic Union in the post-Soviet space, and the Arab League and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).Footnote 39

The relatively new scholarship on regional migration governance has several shortcomings. First, most attention is on intergovernmental processes, capturing less the importance of NGOs and other non-state actors, especially those involved informally. Second, studies rarely advance a comparative regional perspective. In contrast, my account demonstrates how regional governance architectures have emerged in both the Balkans and the Middle East.

Polycentric governance from a relational perspective

Studying transit migration governance requires analytical leverage to deal with complex relationships, which polycentric governance theories are well equipped to address. Michael Polanyi first developed the concept of polycentricity; he considered it a social system of decision-making centres with limited yet autonomous authority, operating under an overarching set of rules. The success of governance does not depend on any central authority, but on the self-organisation of various ‘centres’ alongside shared rules.Footnote 40 Polycentricity gained more attention under governance studies with Vincent and Elinor Ostrom's significant work on local management of common resources, and especially E. Ostrom's 2009 Nobel prize in economics.Footnote 41 Her analytical framework is consistent with game theoretical models considering that decentralised agents operate in an ‘action situation’ synonymous to a ‘game’.Footnote 42

Various studies built on these founding ideas of viewing polycentricity as a complex form of management comprising multiple centres of decision-making.Footnote 43 Polycentric governance has been researched in complex economic systems,Footnote 44 development,Footnote 45 natural resources such as forests,Footnote 46 water,Footnote 47 and climate change,Footnote 48 and recently in migration.Footnote 49 In polycentric governance, cooperation, competition, and contestation exist among the multiple agents involved, but their overlapping authorities are no longer seen as a pathological situation. Overlapping authorities are a result of the need to have division of labour to deliver services, cooperate, and exchange at different scales, structuring the governance process.Footnote 50

However, as argued elsewhere, much of the existing analysis primarily considers institutions and actors that participate in polycentric governance, while their social relationships’ capacity to create order has been neglected.Footnote 51 I build on Jan Scholte's approach towards polycentric governance. His early ideas and subsequent work focused on the global realm, viewing polycentrism as generic patterns of multisited regulation with dispersed and trans-scalar character.Footnote 52 This approach is well suited for studying transit migration governance, requiring complex place-based solutions across various centres of formal and informal authority in different regions. My goal is to shed light on how power-laden mechanisms underpin relationships between the various actors.

In order to do so, I further draw upon IR relational theories. They demonstrate that regularly repeated social interactions form relational structures in international politics, which in turn enable and constrain actors’ behaviours. Such structures can be formed through social movements,Footnote 53 international networks,Footnote 54 or path-dependent processes.Footnote 55 The resulting relationships can be hierarchical or anarchical,Footnote 56 fragmented or integrated,Footnote 57 or can emerge from linkages to specific contexts.Footnote 58 Configuring such relationships is at the core of my approach, as several mechanisms underpin what binds together the various actors involved in transit migration governance in a particular region, producing power structures that embody both formal and informal rules.

I further argue that interactions among agents seeking to govern transit migration do not necessarily lead to rule-based institutions or initiatives, as governance scholarship often thinks.Footnote 59 These relational architectures are much less institutionalised, contextually specific, and shaped by different political regimes – democratic, semi-democratic, authoritarian – and stronger or weaker institutional capacities of states within a particular region. These configurations are often the undercurrents that offset official arrangements or become more or less aligned with them. Although there are clear centres of authority, such as transit states and international organisations, in weak and fragile states actors officially mandated to deal with transit migration interact with NGOs and other private actors in more informal ways, which when repeated form governance architectures that are both formal and informal.

Regarding the mechanisms underlying these relations, I draw from Peter Hedström and Richard Swedberg who consider these as ‘analytical constructs that provide hypothetical links between observable events’.Footnote 60 Such mechanisms can be isolated on the basis of their properties linking entities through different activities.Footnote 61 Here such properties are considered the different ways power is exercised by different entities (‘centres’). Therefore, in this article capturing patterns of durably established social relationships rather than tracing causality, I do not treat mechanisms such as cooperation, coercion, conditionality, containment or contestation in causal ways, but as regularities occurring in specific circumstances,Footnote 62 that need to be treated contextually.Footnote 63 Mechanisms are formally or informally applied between actors, and political regimes shape how certain mechanisms are foregrounded. For example, in regions where authoritarian regimes dominate, mechanisms with more coercive elements come to the fore; in regions with democratic regimes, more consensual politics will be at play. How mechanisms operate should be scrutinised by empirical investigation,Footnote 64 as I do shortly.

I consider cooperation a social phenomenon, rather than only embedded in interactions among states and international organisations,Footnote 65 or based on rational choice models of ‘interactions among egotists’.Footnote 66 It is a complex mix of interests, beliefs, and values that drive cooperative behaviour.Footnote 67 From a polycentric governance perspective, this entails collaboration between multiple parties working across boundaries to solve a common problem that no party can solve on their own, while sharing power without vertical hierarchies.Footnote 68

A relationship based on conditionality entails power asymmetry whereby one actor attaches specific conditions to the distribution of benefits to another. Conditionality is usually a formal intervention of international institutions, attaching conditions of compliance to specific policies in exchange for membership or other benefits for recipient countries.Footnote 69 Such power relations are asymmetric and can be underpinned by competing institutional logics of the actors involved.Footnote 70

In a containment relationship one actor seeks to limit the spread of another actor's ideas, practices, or people, in order to protect their own territory. In migration governance, containment policies seek to thwart migrants’ autonomous movements and prevent them from spreading.Footnote 71 In Italy, for example, containment has inspired the so-called ‘hot spots’ approach, further associated with refugees’ ‘confinement’ and ‘dispersal’ in reception centres scattered throughout the country.Footnote 72 Containment can be pursued also through various techniques, which David Fitzgerald sums up as ‘a landscape of domes, buffers, moats, cages, and barbicans’ that prevent the ‘unwanted from finding refuge’, but become difficult to enforce once ‘a movement is channeled by social networks or a developed people-smuggling industry’.Footnote 73

Co-optation entails ‘significant socialization processes leading to conformity with and commitment to a particular set of political norms’Footnote 74 and practices conforming to a pre-set world.Footnote 75 In polycentric governance, subsidies and government programmes can occasionally co-opt ground-based movements.Footnote 76 Tacit toleration is an informal mechanism where one actor chooses to overlook the transgressions or undesirable practices of another, for the sake of undisclosed interest or the inability to contest. Actors can also be in a relationship of contestation, where policies or practices are disputed by either or both. Contestation in polycentric governance is essential because ‘abstract and underoperationalised social ideals cannot be imposed on the participants by an overarching authority’, but need to be ‘given content by the web of social actors’.Footnote 77 An actor can further use the soft power of attraction rather than coercion or payment to achieve certain goals,Footnote 78 or engage in domestic or international alliance politics, either in support of or against another actor.

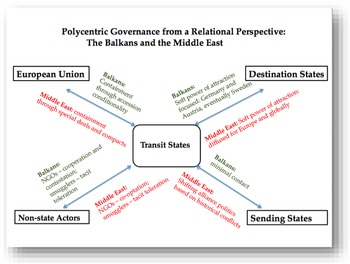

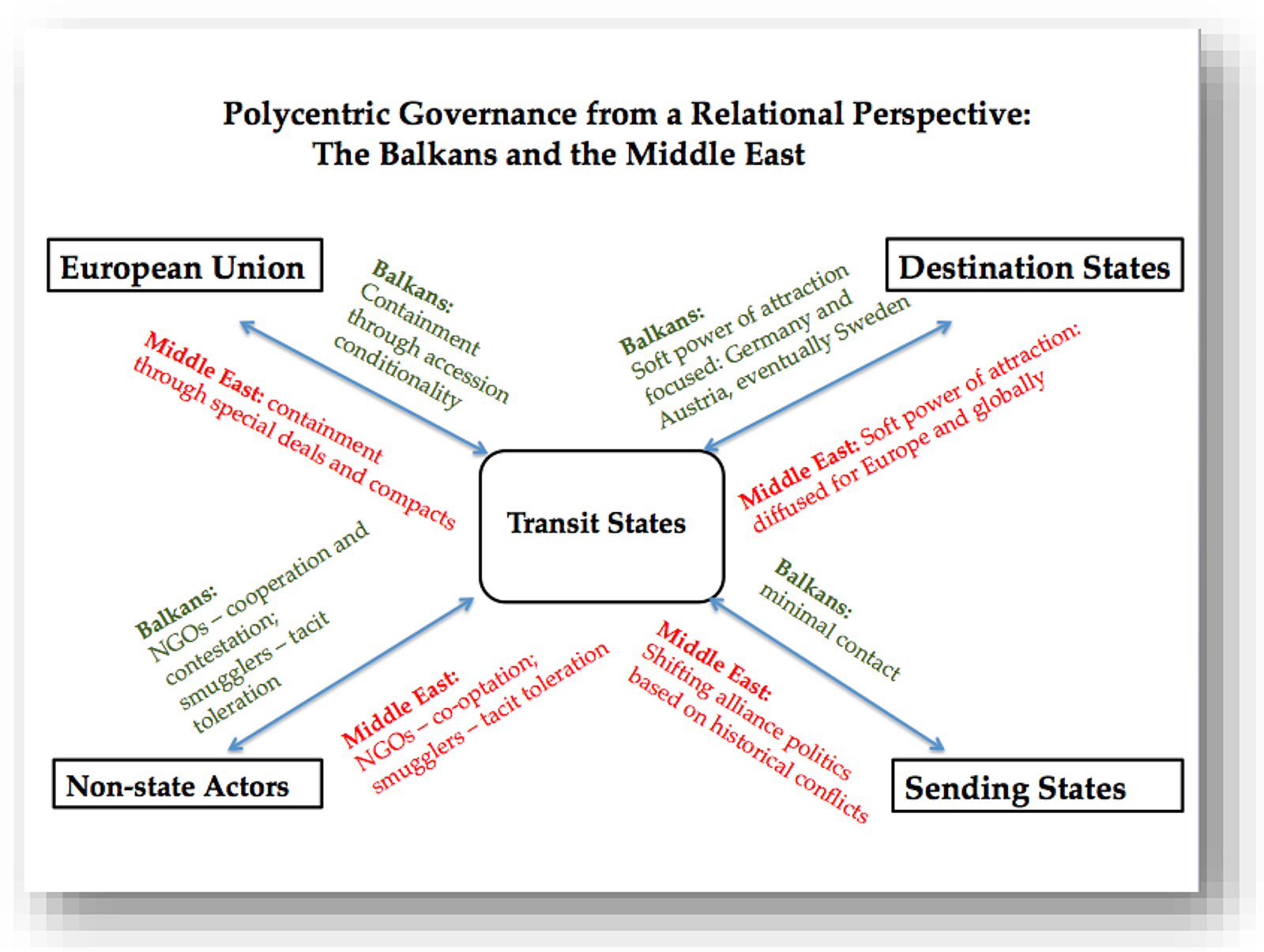

Figure 1 summarises the configurations of these mechanisms that build the relational architectures of transit migration governance in the Balkans and the MENA regions. These are based on a transit state's relationships with: (1) international organisations; (2) NGOs and other private and non-state actors; (3) destination states; and (4) sending states. Countries in both the Balkans and the Middle East are sending states for large waves of emigrating citizens, but also transit states for refugees and irregular migrants from war-torn regions. In the European neighbourhood, where the Balkans and the Middle East are located, the EU is a major supranational organisation to which transit states relate. The UNHCR plays an important role, as does the International Organization for Migration. NGOs, but also businesses, smugglers, and militants, as non-state actors also engage in migration governance. When migrants exercise agency, they can be also part of this relational dynamic. Destination states are those that transit migrants strive to reach. Sending states are their original home states. These power-laden relationships bind these four sets of actors in an architecture of transit migration governance. While my approach does not exclude that ad hoc relationships may form in crisscross ways, a feature of polycentric governance, it focuses on the skeletal frames that create the regional architectures.

Figure 1. Polycentric governance from a relational perspective: The Balkans and the Middle East.

How do such governance architectures remain relatively coherent in a particular region? Formal institutions have established certain legitimacy, although such can be contested. The question is: how does moving away from formal rules invest informal relationships with legitimacy to facilitate transit migration governance? This is especially relevant as informal governance ‘holds an aura of the covert and exclusive’.Footnote 79 Durable interactions could establish informal institutions as ‘socially shared rules, usually unwritten, that are created, communicated, and enforced outside of officially sanctioned channels’.Footnote 80 Informality could gain legitimacy when unwritten agreements exist in the absence of formal rules, when they specify existing formal rules that are ambiguous, when they radically depart from existing formal rules but do not diminish the former's existence,Footnote 81 and when bureaucracies circumvent political limitations on their autonomy.Footnote 82 In weak states where legislation is difficult to enforce institutionally, and decision-making is more contingent on a political regime's ‘rules of the game’, such a repeated mixture of formal and informal relationships develops the fundamentals of mutual expectations and adaptation.

The weakness of statehood in various world regions provides ample opportunities for informality to be legitimised in governing transit migration. In the absence of engagement from state authorities, international organisations, such as NGOs, can take on more responsibility by providing services for those in transit. Even the activities of smugglers and militants can gain local legitimacy, because they challenge dysfunctional rules but do not diminish the existence of formal, governing institutions.

The following empirical section unpacks the configurations of relationships in transit migration governance, represented through a snapshot in time (late 2010s). My framework does not rule out that different power-laden mechanisms could enter the social relationships and reshape actors’ behaviours over time. Especially informal relations can be relatively fluid. However, the durability of social structures that form the regional governance architectures may create obstacles to such new mechanisms entering or taking hold in governing. I draw on evidence from transit states on the Balkan route, particularly North Macedonia, Serbia, Kosovo, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, and Slovenia, part of former Yugoslavia. I further discuss the larger MENA region, focusing primarily on Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan as important transit states prior to and during the current forced migrations from Syria. I chose to compare relationships in these two regions, as they are part of the larger European neighbourhood and tackle similar transit migration flows primarily from Asia and the Middle East. In the Balkans, the countries of former Yugoslavia display post-communist legacies and a mixture of relatively weak and stronger states; in contrast, the Middle East contains competitive authoritarian or authoritarian regimes, where state capacities are even weaker.Footnote 83 I bring ample evidence from secondary sources derived from international and local media.

The Balkans

The Balkan region emerged out of violent ethnic warfare following the 1990s collapse of socialist Yugoslavia, when large refugee flows spread to Europe, the Americas, and Australia. At the time they were primarily Serbs, Croats, Bosnians, and Kosovars. The 2014–16 refugee wave was different. In 2015 alone EU's border agency FRONTEX registered close to 800,000 irregular crossings compared to 43,000 in 2014.Footnote 84 The bulk of refugees and transit migrants came from outside the region, mostly from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Pakistan with the aim of reaching Western Europe. Migration during this period is associated with both mobility and immobility. Especially North Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia, and Slovenia turned into transit states before the 2016 closing of the Balkan route. Yet, a new route opened in 2017–18 encompassing Albania, Kosovo, and especially Bosnia-Herzegovina. Many migrants were left ‘stranded’ in parks, camps, and other public buildings, hoping to reach Europe but unable to move,Footnote 85 despite their determination to keep going. As Gerard Knaus, founding chairman of the European Stability Initiative, argued, if someone has crossed five or six international borders already, they are not likely to give up crossing into the EU.Footnote 86

Several mechanisms underlie the configuration of transit migration governance in the Balkans, which can be briefly characterised as ‘reluctant gatekeeping while buck-passing’. Officially, these are asymmetric mechanisms of conditionality for future EU enlargement, linked to containment measures. The Balkan states’ role is to contain transit migration into Europe, or to facilitate it in official ways. Yet, another layer of informality and self-organisation exists if one looks deeper. Transit migration is often informally tolerated among states with relatively weak institutions that pass the burden on to other states. On another scale, NGOs, holding a certain level of autonomy, take on transit migration by contesting dysfunctional state policies, or the lack of them. On another, clandestine level, smugglers, taking advantage of migrants’ desire to reach other destinations, face both official contestation and informal toleration. In this region's architecture, relationships between transit states and sending states are minimal, while those with EU destination states are strong. Destination states are attractive to migrants because of either their formal policies or the informal knowledge among migrants of opportunities for family reunification and integration over time.

EU accession conditionality with transit migration containment

Two asymmetric power mechanisms underpin the relationship between the EU and Balkan states: EU accession conditionality coupled with the containment of refugee and transit migration flows. In contrast to previous enlargement waves towards Eastern Europe, EU conditionality in the Western Balkans has been defined by the need to strengthen weak postconflict states, through instruments embodied in Stabilization and Association Agreements. Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia signed such agreements, as did Croatia prior to joining the EU in 2013. While conditionality required Balkan states to meet certain thresholds of democratic standards to gain future membership, its long and tedious process effectively put the breaks on such enlargement. Conditionality eventually became an interventionist political process to ensure that reforms were introduced without many stand-offs against the EU.Footnote 87 Especially the 2014–16 migration wave necessitated reforms to asylum and migration systems not introduced previously. The EU promoted its model of border managementFootnote 88 in the Western Balkans and required an update of local asylum systems.

With the EU's endorsement, in 2015, countries on the Balkan route opened a transit corridor for transporting refugees across their territories into Western Europe. Such policies were formalised, although it was unclear how refugees would transit legally under EU law.Footnote 89 Transit was often justified on humanitarian grounds, especially in Serbia and Croatia, where empathy towards current refugees was linked to recent memories of refugees’ displacement during the 1990s wars of Yugoslavia's disintegration.Footnote 90 Formal and informal practices worked hand in hand. Under UNHCR pressure, refugees were asked to express their intent to apply for asylum at border points and receive a ‘de facto transit visa’, called a 72-hour paper.Footnote 91 While many expressed such intent officially, the majority did not file for asylum in these countries according to Dublin regulations, but pressed further towards Western Europe. On their part, although having adjusted to EU requirements, Balkan states justified their transit state status by discouraging refugees from remaining in their territories. As Croatia's former Prime Minister Zoran Milanovic appealed to refugees: ‘You are welcome to Croatia and to pass through Croatia … But continue. Not because we don't like you, but because this is not your final destination.’Footnote 92

Containment is not officially spelled out in EU documents, nor is it official vocabulary of Balkan states. Yet, it underpins this relational link in the governance architecture. In October 2015 EU and Balkan states adopted a plan to coordinate a response to the crisis. It included not only improving information exchange, registering migrants, and developing temporary reception centres, but also deploying FRONTEX as a security arrangement available only to EU member-states at the time.Footnote 93 Leaders of transit states were placed in a new lucrative position to ‘sell their services as proxy migration controllers’.Footnote 94 As Andrew Geddes and Andrew Taylor observe, Balkan states ‘were not unwilling pupils’ to learn EU border practices. The Slovenian Ministry of Interior, for example, welcomed them as measures for the country's EU integration, while simultaneously putting ‘restrictive provisions such as border controls’ in place. Ministries of interior of other Balkan states also benefited from these arrangements.Footnote 95

Considering the discussed containment through conditionality, one usually thinks of a bifurcated relationship between power-holders of an asymmetric nature: the EU as a supranational institution imposing policies on less powerful Balkan states that try to adopt or evade them. However, looking deeper through the lens of polycentric governance, one can discern ways in which Balkan states retained some power to govern transit migration less formally. Prior to the 2014–16 wave, migration-related agreements were signed to readmit persons residing without authorisation in the EU, and to reintegrate returnees.Footnote 96 Yet, Balkan states were ‘neither willing, nor able to process the number of asylum applications that could be potentially lodged by all the persons transiting through the region today’.Footnote 97 Weak institutions make asylum systems easy to abuse when getting transit migrants to their desired destinations.Footnote 98 In addition, Balkan states resorted to ‘push-backs’, not officially sanctioned, when authorities forcibly returned migrants to another stateFootnote 99 or pursued selective registration.Footnote 100 Such practices somewhat contained transit migrants within the region, and passed the buck onto other states for dealing with them. They created tensions between Serbia and Croatia in 2015–16.Footnote 101 Croatia's strict EU border control resulted in a bottleneck in neighbouring Bosnia-Herzegovina towards the West, while Serbia did little to control transit migration flows.Footnote 102 Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic and reinforced border closures, Croatian police have been accused of spray-painting migrants with crosses when pushing back from Bosnia's border with Croatia.Footnote 103

Transit migration and non-state actors

I argue that in the Balkans, where democratisation processes have been in place for almost three decades, and strengthened due to EU conditionality, NGOs have gained some degree of autonomy, although not fully. Such relative autonomy has been especially visible among Muslim-based NGOs, as they have operated in support of minorities in political environments where majorities have been primarily Christian, either Orthodox (North Macedonia, Serbia) or Catholic (Croatia, Slovenia). Bosnia-Herzegovina, Albania, and Kosovo are Muslim-majority states.

Therefore relationships between NGOs and governments in transit states have been often based on the ability of such relatively independent non-state actors to cooperate or contest existing policies. Some have been grassroots organisations engaged in anti-systemic solidarity with migrants, while others have taken part in humanitarian relief operations alongside government and international organisation guidelines. In this region, however, NGOs have had a rather independent voice when cooperating with one another or contesting authorities, thereby creating a layer of informal self-organisation away from officially sanctioned policies.

NGOs were often mentioned in the news in 2015 with their support of refugees passing through the Balkans. Civil society organisations quickly compensated for the initial absence of state-provided accommodation and services, erecting temporary refuges and providing meals, clothes, and legal services.Footnote 104 They concentrated in places alongside the refugee route. There was an understanding that although refugees and other transit migrants may not permanently stay in the Balkans, their human rights should be respected while they are there. In North Macedonia, Muslim and international NGOs were the first to engage, attracting hundreds of volunteers, many of whom contested the violent treatment of refugees by the state.Footnote 105 Some launched local protests and advocated for policy changes, such as the LEGIS NGO that lobbied for the introduction of the above-mentioned 72-hour transit paper.Footnote 106 In Serbia many volunteers joined domestic and international NGOs, while civil society organisations in Croatia vocally supported refugee rights. They also collected food, blankets, and other donations. Activists across the region cooperated with each other, but contested the strict security measures implemented to deal with the refugees.Footnote 107

Muslim organisations in the Balkans retained relative autonomy. Piro Rexhepi observes, the production of European border regimes, mixed with Islamophobia, introduced a distinction between Balkan Muslims as secular populations and the ‘Islamists and Jihadists’ from outside Europe. State-sanctioned Islamic institutions especially in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, and North Macedonia labelled dissident congregations as ‘radicals’. Yet, Muslim community-based organisations and some mosques were more independent from their official denominations. Especially in North Macedonia in 2015, some Muslim NGOs rendered the strongest support for refugees. Humanitarian organisations such as Association Veli & Arif provided assistance and kept their distance from official Islamic institutions.Footnote 108 Once the new transit route emerged in 2017–18 to pass through predominantly Muslim countries such as Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Kosovo, it was derogatively called the ‘mosque route’.Footnote 109

NGOs continued to play an important role also during the ‘stranded’ phase of transit migration. In 2019 NGOs in Croatia, Serbia, and North Macedonia became alarmed that migrants had been exposed to illegal expulsions every day and been mistreated and humiliated.Footnote 110 A lack of capacity to accommodate them has been especially grave in Bosnia-Herzegovina. NGOs warned about a potential humanitarian disaster due to overcrowded camps and refugees sleeping in parks and squats.Footnote 111 Besides pursuing advocacy, NGOs continued to fundraise for food and other donations.

Smuggling networks have been operational at yet another, clandestine, level in the Balkans long before 2014–16, as has been combatting them through various methods. When the transit corridor became official in 2015, migrants did not have to rely on clandestine smugglers to cross borders.Footnote 112 Their movement was officially facilitated towards the EU. Tackling migrant smuggling increased also with EU requirements to strengthen cooperation in human trafficking. Such requirements were embedded in the EU Action Plan against human smuggling and demonstrated by joint actions, such as Operation Kostana (2015),Footnote 113 whereby police forces of seven countries within and outside the EU jointly acted at the Serbia–North Macedonia border together with Europol.Footnote 114

Yet, in relatively weak Balkan states, challenged by minimal economic opportunities and corruption, it is not surprising that transit states have, on occasion, tacitly tolerated such activities. Smuggling is a booming business, worth €2 billion a year.Footnote 115 For example, in the summer of 2015 a central Belgrade district had become a hub for transit migration, but authorities did little to remove the visibly operating human smugglers.Footnote 116 Locals were also involved in supporting both migrants and smugglers, as witnessed on the Serbia–North Macedonia border.Footnote 117

Nina Perkowski and Vicki Squire arrive at similar conclusions about the interplay between formal and informal interactions related to human smuggling. Their interviews with refugees and other migrants who traveled to Germany in 2015 along the Balkan route recount that the latter experienced ‘considerable amount of organization and logistical support … from the very police forces that would later impede others from traveling on’.Footnote 118 The authors question a conventional view that smuggling can be reduced by anti-smuggling measures, as there has been a co-relationship between both. Extraction of profit from people on the move has been pervasive, and a significant factor behind what the authors consider a failure of the European anti-smuggling agenda.Footnote 119

Balkan states in relationship with destination and sending states

Two mechanisms identify the relationship between Balkan states and destination states: initial cooperation through the formalised transit corridor and destination states’ own soft power of attraction. The formalised corridor had two immediate destination states within a close reach of the region: Austria and Germany, both part of the EU, therefore also implicated in overlapping migration-related governance. This corridor extended to Germany after thousands of refugees were stranded at the Budapest railway station in summer 2015, and when Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel announced that she would not close the country's borders.Footnote 120 Most people transiting through Slovenia, also an EU country, did not ask for asylum there, but continued on to Austria. At the peak of the refugee wave in 2015, Austria had the third highest asylum applications in the EU, after Hungary and Sweden.Footnote 121 Austria closed its borders in January 2016, but remained attractive as a destination state, although it served as a transit state to Germany too. As Julija Sardelic demonstrates, Germany was the most desired destination as it decided to examine asylum applications of third-country nationals whose first point of entry was not Germany.Footnote 122

Additional reasons made Austria and especially Germany attractive to refugees from the Middle East. Both countries had experience with hosting refugee-based populations from the wars of former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Geospatially, they were also closer to the Balkan region than Sweden, for example, a country considered by many Middle Eastern refugees an ultimate destination. Germany's attractiveness was due to its open-door policy and ‘we can do it’ rhetoric.Footnote 123 Young skilled workers were needed against the backdrop of an ageing population.Footnote 124 Austria also tried to lure refugees to fill job shortages, despite rising anti-immigrant rhetoric that has gained traction over time.Footnote 125 Family unification was also a pull factor, as Germany has previously hosted hundreds of thousands of Afghani, Iraqi, and Syrians who have become diasporas. Germany was an end destination for many of the 2015 wave, evident in that most Syrian refugees have wanted to stay in Germany.Footnote 126

The least pronounced relationships have been between Balkan states and Middle Eastern and Asian sending states where the migration wave originated.Footnote 127 Historically socialist Yugoslavia was part of the Non-aligned Movement, in which Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq were members along with other Middle Eastern states. After the Cold War only Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina retained observer status in this organisation. Previously, Balkan states had not been a destination for massive voluntary or forced migration from the Middle East. Therefore, although most of them had bilateral relations and embassies in the respective Middle Eastern capitals, their foreign policies rarely concerned migration and citizenship issues. The only more recent exception was Serbia, seeking to toy with influences alternative to that of the EU and to reinvigorate its relationship with Iran. This concerned Iranian refugees who had tagged along with the 2015 refugee wave from Syria. In 2017 Serbia opted for a visa-free regime with Iran, but less than a year later abolished it, citing abuse, as some were seeking to illegally enter the EU once they got to Serbia.Footnote 128 Therefore, most of the Balkan states’ relationships with the sending states were indirectly influenced through their relationship with the EU.

The Middle East

Violent conflict has recurrently displaced populations throughout the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), many of whom have sought to transit to Europe or other global destinations. Especially the 1948 and 1967 Arab–Israeli wars, the 1971–89 Lebanese civil war, the 1978 Iranian Revolution, the 1991 Gulf War, military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq in the 2000s, and the war in Syria since 2012 have caused massive population displacements. As most countries in the region are authoritarian and do not respect refugee rights detailed in the 1951 Refugee Convention, they also do not grant asylum. Historically a source of emigration, MENA states did not have the political will to accommodate immigration; thereby irregularity grew in parallel with immigration.Footnote 129 This is how an international refugee regime's power diminishes formally, opening up for substitutive informal relationships to kick in.

Displaced populations can be bona fide refugees, whether given asylum or not. But they are rarely able to travel directly from their country of origin to their desired destinationFootnote 130 and often enter mixed flows of irregular migration. Asylum seekers may remain in the transit state and seek to cross illegally into another state.Footnote 131 Examples include more than 200,000 transit migrants bound for Europe but unable to reach it due to a lack of visas, and labour migrants employed in the informal sector without permits.Footnote 132 Transit migration through the Middle East consists of mixed flows of people not only from the region, but also those from Asia and Africa. A large-scale 2017 survey among Palestinians and Kurds in Europe demonstrates that many in the now-established diasporas transited on their first journey through Jordan, Lebanon, or Turkey and then through Greece on the Balkan route or through Malta, Spain, or Portugal.Footnote 133 Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan have been transit states for decades beyond the current Syrian warfare and deserve closer attention.

The regional architecture of polycentric governance of transit migration in the MENA region is one where hierarchical and coercive power relationships dominate. These relationships are at the core of the formal and informal ‘rules of the game’, which shape actors’ expectations and the conditions of possibility they face when responding to transit migration. In contrast to the Balkans, where region-wide policies towards meeting EU enlargement norms and legal requirements define how states handle transit migration, EU policies in the MENA region are less unified regionally, but more target an individual country's interests to entice them into gatekeeping. Hard bargaining dominates, whether through political compacts offering financial benefits for hosting refugees or by threatening to break such agreements to extract further benefits, most notably voiced by Turkey. NGOs have less autonomy, whereas smugglers are tolerated and militant groups can control specific territories and play a role in governing transit migration. In contrast to the Balkans, targeted destination states are not only European. Relatively remote geospatially, European destination states play a less pronounced role in this regional architecture than sending states. Sending states are often proximate or neighbours to the MENA transit states, entangled with them in historical conflicts that continue to the present day. Intrastate and international conflicts manifest in geopolitical alliances, which in turn shape transit migration governance.

Transit migration containment through special deals and compacts

Transit migration governance in the MENA region has included states and international organisations. Roberto Pitea observes that the lack of formalised understanding of what constitutes ‘transit migration’ has manifested as legal treatment of irregular migration. This has been the case in Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq, which adapted their existing policy instruments to counter irregularities.Footnote 134 Such practices have been challenged by the UNHCR, which takes care of refugees, returnees, and internally displaced peopleFootnote 135 and advocates for a universal perspective of their rights. The IOM has taken on some roles reserved previously for the UNHCR, namely care of asylum seekers and refugee return.Footnote 136 In 2002 the EU created a Dialogue on Transit Migration with Mediterranean countries for short-term cooperation to combat irregular migration, and long-term development cooperation for better joint migration management.Footnote 137 These policies expanded and deepened over time. The following discussion focuses primarily on responses involving the EU, to extend the comparison with the Balkans.

Containment as a mechanism underlies the relationship between the EU and Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan. Here it largely manifests through special deals and compacts based on a ‘tit-for-tat’ power relationship. Such deals involve large sums of EU financial transfers for humanitarian assistance to Syrian refugees, in exchange for tightening border controls, curtailing illegality, and breaking smuggling networks. Rather than being passive recipients, transit states have engaged in ‘refugee rentierism’,Footnote 138 seeking to obtain bargains from the EU that go beyond funding the refugees.

Such deals were also enabled by transit states not subscribing to the 1951 Refugee Convention.Footnote 139 The transit states may abide by customary international law not to return refugees to places where their lives would be endangered (non-refoulement principle), but they still treat them idiosyncratically, and much more informally compared to transit states in the Balkans, legally bound by the refugee regime. Turkey has given a temporary protection status to Syrian refugees, but not to other refugees. Syrian refugees were initially labelled as ‘guests’, but such favourable treatment vanished when competition for jobs and scarce resources increased.Footnote 140 Lebanon has applied some provisions from the Refugee Convention voluntarily, but is reluctant to recognise refugees especially from neighbouring states, and shifts responsibility for them to third parties, notably the UNHCR.Footnote 141 Jordan has no national legislation governing refugee matters, but has similarly cooperated with UNHCR to register refugees.Footnote 142

Conditionality as a mechanism underpinned initially Turkey's relationship with the EU. For an entire decade until the 2016 special deal, EU policies included increased scrutiny of the country's human and minority rights performance and rule of law, similarly to processes related to the Western Balkans. A visa-free regime for Turkish citizens, originally contemplated as part of such EU's conditionality, did not materialise. Controlling borders and migrants mobility was part of the relationship between EU and Turkey prior to the 2016 deal.Footnote 143 However, the 2016 deal was a step-change. It was deployed as a tool of crisis management, a humanitarian action jointly operated with the EU in the context of the larger conditionality. Turkey's foreign ministry considered the deal successful as it brought additional funds,Footnote 144 although EU accession negotiations were frozen in late 2016 due to Turkey's growing authoritarianism.

In essence, the deal envisaged the containment of illicit migration on a transit journey to Europe. It sought to prevent irregular migration flows from crossing into the EU, and to return to Turkey third-country nationals who manage to cross illegally. The EU promised €6 billion in assistance for the Syrians in Turkey. As Soykan argues, ‘Turkey wanted the money and the EU wanted Turkey to stop migration to Europe, so the government [of Turkey] became the gatekeeper that kept Syrians in Turkey.’Footnote 145 Turkey is currently hosting over 3.5 million registered Syrian refugeesFootnote 146 in government-run camps and self-accommodation in urban areas. In response to the deal, 1,582 third-country nationals, including 279 Syrians, were resettled in Turkey.Footnote 147 The deal also thwarted temporarily individuals’ intentions for further transit either by rendering going to Europe less desirableFootnote 148 or by offering job opportunities that made some abandon their early plans to move.Footnote 149

The deal was initially considered a success, yet border externalisation did not proceed as intended.Footnote 150 Crude power politics set in, fostered by authoritarian practices. When in 2019 arrivals from Turkey grew in Greece, Turkey slowed down procedures to readmit third-country nationals.Footnote 151 It retained its hard-bargaining power by occasionally threatening to open the border to Europe for refugees.Footnote 152 It even delivered on this threat more recently, when in February 2020 Ankara suddenly stopped blocking refugees passing into Europe. As a result hundreds of refugees arrived at the borders of Greece and Bulgaria.Footnote 153

EU's compacts with Lebanon and Jordan did not entail an enlargement conditionality mechanism, but offered the hosting of Syrian refugees in exchange for financial benefits. Thereby the compacts ‘bilateralised’ EU's neighbourhood policy beyond its original intentions to ‘create a level-playing field’ among countries aspiring for membership.Footnote 154 The Lebanon Compact facilitates the refugees’ temporary stay, while the Jordan compact seeks to create more job opportunities. Through the Lebanon Compact, the EU pledged €400 million (2016–20) for education, youth, medicines, solid waste, counterterrorism, job creation, and legal aid for both Lebanese and refugees.Footnote 155 Through the Jordan Compact, the EU pledged €747 million (2016–17) for humanitarian aid, social inclusion, microfinance, justice and political reform, and creation of 200,000 jobs for Syrian refugees and Jordanian citizens in exchange for relaxed conditions to export Jordanian products into the EU.Footnote 156

Although both compacts have a different substance, they both aspire to contain onward migration towards Europe by emphasising the self-reliance of Syrian refugees and creating incentives to prevent transit.Footnote 157 As a EU diplomat put it: ‘The main objective … is to stabilize refugees, so that they don't move on to Europe. This is done through “development projects,” such as investments in infrastructure and community-based projects.’Footnote 158 The two compacts also solidified local tendencies to increase border controls. Until 2014 Lebanon had an open border policy for Syrian refugees, while Jordan limited entry specifically for Palestinians from Syria.Footnote 159 The EU's approach coupled refugee governance with security, border management, and development concerns, seeking to safeguard its own security.Footnote 160 This helped transform ‘the norm of burden-sharing into a practice of migration containment’.Footnote 161

However, such measures were ineffective. Containment of transit migration may have been officially agreed upon, yet fragile statehood creates conditions for informality to thrive. Concerns for exploitation, mismatch between labour skills and demands of local economies, detention, deportation, and human rights abuseFootnote 162 created conditions for further migration, including transit. Also, the porous borders of these fragile states facilitated transit or illicit migration. In Lebanon formal state agencies are not always present in border areas.Footnote 163 Nor are information systems available at all border crossings, especially with data concerning non-Lebanese citizens.Footnote 164 Jordan also has porous borders, facilitating the transfer of people and weapons from neighbouring states, including Syria.Footnote 165 Moreover, a 2019 UNHCR survey of Syrian refugees revealed that 75 per cent of them intended to stay in the host country, while 20 per cent openly considered moving onto a third country with a ‘transit migration’ mindset.Footnote 166 Such a gap between official policies and refugees’ actual intentions opened up further space for informality, discussed shortly.

NGOs and other non-state actors

In polities with authoritarian or competitive authoritarian regimes in the MENA region, NGOs provide a major share of the humanitarian aid and refugee services. While officially retaining some autonomy, many are still co-opted in their relationship with transit state institutions, and often serve as their extended arms. From a polycentric governance perspective, such a relationship tilts decision-making power towards state authorities, while actors adjust to such formal and informal power asymmetry. Such a trend is especially visible in Turkey as a centralised state with growing authoritarianism. Although the number of associations increased with Turkey's democratisation in the 2000s, mutual distrust between state and civil society organisations prevails, especially after the crackdown following the 2016 attempted coup d'etat. Numerous NGOs criticised that ‘the government has its favored organizations and cooperates only with them.’Footnote 167 As Zeynep Sahin-Mencutek argues, the most active NGOs tackling what the state presented as a humanitarian emergency were close to the government: the Turkish Red Crescent, having a semi-state status foundation, and the Foundation for Human Rights and Freedoms and Humanitarian Relief.Footnote 168 INGOs also needed permission from either central or provincial authorities and had to rely on government data to deliver services,Footnote 169 or were subjected to heavy monitoring.Footnote 170 NGOs stepped in to deliver language education, but mostly those aligned with the government were sponsored to work on large projects.Footnote 171 Refugee-based organisations also emerged, but were mostly organised in informal charitable and religious networks. They avoided challenging the state, because of the refugees’ legal precarity and temporary arrangements.Footnote 172 Hence, although there was a period when Turkish civil society gained more independence, after 2016 state and non-state actors had to adjust to the government's regaining decision-making power over refugees and transit migrants.

Jordan and Lebanon have also sought to co-opt NGOs, although more indirectly, since in these countries responsibility for the protection of refugees and their ultimate departure has been heavily transferred onto UN agencies. Formal and informal relationships factor in UNHCR's role in refugee governance, to the extent that some consider it a ‘surrogate state’.Footnote 173 In Jordan, NGOs partnering with the UNHCR have collaborated with ministries and municipalities for service delivery. But they act carefully when lobbying relevant ministries, reluctant to question their policy positions and fearful of being denied access to refugee camps or other areas.Footnote 174 In Lebanon, where the UNHCR has traditionally played a stronger role, co-opting of NGOs has taken place more indirectly: by restricting the UNHCR's right to register refugees after 2015, and by making it difficult for NGOs to rely on UNHCR data and support the delivering of humanitarian services.Footnote 175 Moreover, Western-funded NGOs often compete with sectarian-based networks, especially in Lebanon where another non-state actor, the militant Shia organisation Hezbollah, has ubiquitous presence.Footnote 176

Transit states in the MENA region also have an uneasy relationship with smuggling networks. In 2019 Turkey made headlines by formally breaking up a smugglers’ ring operating in four Turkish provinces; the ring was connected to Ukraine, Greece, and Italy and had helped Iraqis, Afghanis, and Syrians cross into Europe by land and sea.Footnote 177 Iranians have also transited through Turkey due to its visa-free travel. However, undercover research has shown that human smugglers are tacitly tolerated while operating openly in cafes in Istanbul, although occasionally experiencing police raids and court cases. One of them argued: ‘The state turns a blind eye to the flow of migrants. Of course they know … But the migrants are a great source of income for Turkey … Our trade is a great support for the national wealth, because every migrant who enters Turkey leaves behind between 3,000 and 10,000 Euros.’Footnote 178

Similarly, official policies have restricted smuggling in Lebanon and Jordan, yet informally tolerated it as part of corrupted practices. Entering Lebanon has been almost impossible without smugglers’ aid, while restrictions on work permits has facilitated migrants to become part of ‘clientelist structures’ in a ‘vivid black market of fake sponsors, brokers, employers and contracts’.Footnote 179 In Jordan, Syrians commonly pay smugglers to bypass Jordanian security forces when fleeing the camps.Footnote 180 The demand for transit migration, especially among Iraqis, has created business opportunities for local Jordanians who have set up bogus travel agencies or added smuggling to their open businesses to bring foreign domestic workers from Asia.Footnote 181

As in the Balkans, it is counterintuitive and also illegal institutionally to include smugglers within the architecture of transit migration governance. Yet it exists informally in the MENA region as well, not least because it does not threaten the transit states’ political order and informally benefits them.

Relationship with destination and sending states

As discussed earlier, significant migrations originating in the Middle East transit to Europe via the Balkans. Hence, similar destination states with relatively open asylum regimes – such as Germany and Sweden – exercise soft power to attract those in the Middle East. Germany recently became highly attractive to Syrian refugees because of the earlier discussed openness of its borders, opportunities to file for asylum regardless of point of entry, and relatively quick integration of refugees into businesses and other programmes. Sweden has been attractive to Middle Eastern war-ravaged populations because of its openness to refugees, at least until recently, and its welfare system.Footnote 182 Family unification plays an important role as well.

However, since the geospatial distance to EU borders, especially from Lebanon and Jordan, necessitates several transit stops, the appeal of European destination states has been more diffuse than in the Balkans. Transit migrants have considered other global options and negotiated destination states along their journey.Footnote 183 Other destinations in Canada and Australia have gained importance. Well-off Syrian refugees in Turkey, for example, have paid smugglers €9–10,000 to reach Europe, €12–13,000 for the UK, and €15,000 for Canada, while some have transited through Cuba, Brazil, or South Africa.Footnote 184

In the MENA governance architecture, formal and informal relationships between transit and sending states are bilateralised and entangled in historical conflicts, where close geospatial proximity shapes how transit migration is governed. Such relationships often transpire in shifting alliances through power politics among ethnic groups or political factions within fragile states and beyond. Nowhere is such a trend clearer than in Lebanon, where political party alliances for and against Syria divide local actors because of Syria's occupation of Lebanon until 2005. Supportive of Assad's regime in Syria, the militant Shia organisation Hezbollah in Lebanon (on the terrorist list internationally but considered a party locally) has been the least welcoming towards refugees in areas under its control. This is in contrast to other local actors with more oversight over Christian, and especially Sunni-inhabited, areas.Footnote 185

Thus, although scholarship tends to think of Lebanon as a transit state making decisions about migration governance in its territory, confessional groups and non-state actors exercise significant informal yet de facto capacities to selectively govern. This governance is not universal regarding refugees and other transit migrants, but is defined by the actor's regional alliances, amities, and enmities. For example, Lebanon's and Jordan's historical conflicts with Palestinian exiled movements has resulted in specific treatments of Palestinian refugees during the current Syrian warfare. Lebanon refused to allow Syrian refugee camps to be constructed altogether, to avoid repetition of the Palestinian experience of building temporarily camps that turned permanent, and enacted high border restrictions on Palestinian entry.

Turkey's relationship with its neighbours to the east is further shaped by instability and wars. Turkey became a transit state for a large wave of Iranian refugees after the 1979 revolution, and those fleeing Iraq and Kuwait after the 1991 Gulf War.Footnote 186 Turkey's tensions with Syria, Iraq, and Iran have existed over colonial and water politics, Turkey's role in NATO, secessionism, and the political activism of mobilised Kurds seeking territorial self-determination from Iraq, Iran, and Syria, besides Turkey. Turkey has also been involved in the recent war in Syria, in combating the Syrian government, and in international alliance politics seeking to defeat the Islamic State. As discussed earlier, Turkey became one of the main countries to host Syrian refugees and other mixed migration flows from this conflict region. It is beyond the scope of this article to demonstrate the effect of all these conflicts on Turkey's transit migration governance. Yet it is important to emphasise that recurrent conflicts along Turkey's eastern and southern borders make them more porous towards large flows of refugees and illicit migrants, including those from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Myanmar, and Bangladesh.Footnote 187 Thus, although there are official policies to govern migration within Turkey, a constant influx of mixed migration flows from neighbouring conflict regions constitutes a recurrent management challenge.

Conclusions

This article advances a novel way of thinking about regional architectures of transit migration governance: a relational perspective on polycentricity. It advocates for a shift away from thinking in institutionalist terms, underpinning the study of migration regimes and regime complexes, but to consider that such governance takes place both formally and informally through power-laden social relationships among four sets of actors in a particular region. These operate polycentrically and on different scales: international organisations, non-state actors, and destination and sending states.

My approach emphasises the importance of informality in building and sustaining regional governance architectures. These do not offset institutional governance arrangements, but either supplement or do not challenge them. Aside from governments and international organisations, the relevant actors adapt to a region's mixture of formal and informal relationships, shaped by political regimes and capacities of the states in which they are embedded. The article provided ample empirical evidence from both the Balkans and the Middle East.

I also identified that migrants, when exercising agency in their own governance, can enter such social relationships. Migrants can become part of NGOs, be private actors or participate through informal networks. For space limitations, empirical engagement with migrant agency has not been at the core of this article. Future research could delve deeper into this problematic, through migrant-based interviews, and ascertain how much migrants’ behaviours are shaped by existing social relationships and the established governance architectures, and how much they themselves shape and challenge these effectively.

This article brings novelty to the larger literature on polycentric governance. Existing scholarship on polycentric governance focuses little on migration politics, per se, and the larger IR literature still emphasises primarily the emergence of formal rules among various actors. This article demonstrates that rule-based and informal arrangements often coexist in transit migration governance, and appeals to open our analytical tools to capture such mixed phenomena. Also, as argued elsewhere, such a relational perspective could be applicable also to other policy areas where formal institutions are absent, are new, weak, or existing rules are difficult to implement. This could concern a variety of policy areas such as environmental politics, economic standardisation, humanitarianism, other aspects of migration and diaspora politics, as well as Internet governance, among others. Finally, by examining the varieties of power-laden relationships that underpin the regional architectures of transit migration, this article also responds to recent calls within the broader scholarship on polycentric governance,Footnote 188 to think on the role of power in more systematic ways.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Käte Hamburger Kolleg/Centre for Global Cooperation Research for sponsoring research for thisarticle, and research fellows associated with it (2019–20) for their excellent feedback. Special thanks to Sigrid Quack, Jan Aart Scholte, VolkerHeins, Frank Gadinger, Marianne H. Marchand, Zeynep Sahin Mencutek, Katja Freistein, Christine Unrau, and Maryam Z. Deloffre. The articlereceived helpful feedback during sessions at the International Studies Association and the Politics and International Studies Department atWarwick University. The author further thanks anonymous reviewers for their excellent insights to improve this article and Warwick University forthe full open access.