INTRODUCTION

In 1920, Father Jos van de Kolk of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus (Missionnaires du Sacré Coeur, MSC) published the article “Six Happy Children from South New Guinea” in the missionary journal Almanak van O. L. Vrouw van het Heilig Hart.Footnote 1 Van de Kolk provided brief biographical descriptions of these six “happy” Papuan children enrolled at the Catholic missionary boarding school in Langgur on the Kei Islands, about 1,000 kilometres from the southern coast of Dutch New Guinea where the children were born.Footnote 2 At the end of the article he appealed to readers:

If only all children and youth of South New Guinea could be raised and educated as these six are! That would make it possible to preserve the poor people of the Kaja-Kajas for the future. But how can the Mission provide such an upbringing for all children? […] the difficulty is that the Mission does not have the necessary means and resources at its disposal; no religious sisters are present in South New Guinea yet, nor is there a school (education system) or a teacher.Footnote 3

In his appeal, Van de Kolk urged readers to donate money to the mission, explaining that their donations would go towards education for all Papuan children.

In 1920, when the article was published, the colonial and missionary presence was confined to the coastal area of South Dutch New Guinea, where “order” had been imposed through military assistance. During these years, Dutch priests opened two boarding schools for approximately fifteen Marind boys in the colonial settlements of Okaba and Merauke (see the sketch map of South Dutch New Guinea in Figure 1). In addition, they reassigned a few eligible Catholic boys and girls (most of them of mixed Chinese or Timorese/Marind descent) to the older Catholic boarding school in Langgur on the Kei Island.Footnote 4 The missionaries hoped to convert all of South Dutch New Guinea. In their opinion, moral and physical disciplining of all Papuan children was essential to this effort. They had, however, lacked the means to this end until shortly after the publication of the article by Jos van de Kolk. Circumstances changed in 1921, when the administration enacted legislation on administrative and cultural matters in South Dutch New Guinea, resettling Papuans in newly established villages and introducing compulsory schooling. Moreover, Dutch missionaries received substantial donations from benefactors in the Netherlands and were subsidized by the Dutch East Indies government to educate Papuan children from 1921 onwards. This support enabled Dutch Catholic missionaries to open over 200 village schools along the south coast and in the hinterlands of South Dutch New Guinea. Hundreds of Keiese and Tanimbarese Catholic teacher families (recruited and trained by Dutch Catholic missionaries in Langgur) worked at these village schools.

Figure 1. Sketch map of South Dutch New Guinea.

While the colonial state invested heavily in primary education for indigenous children, the Catholic missionaries assumed control of colonial education at the administration's behest in South Dutch New Guinea. The introduction of Western education by missionaries had a significant impact on the lives of children, families, and communities in South Dutch New Guinea by instigating radical cultural transformations of Papuan societies. I argue that this radical cultural transformation started with the colonial and missionary presence, rather than, as theologian At Ipenburg maintains, under the Indonesian government in the early 1960s.Footnote 5 The Catholic mission intervened in the lives of Papuan children, as part of a process of bringing about colonial “civilized” subjects and regulating their conduct, in which colonial education was pivotal. In this contribution, I will discuss the history of colonial education in South Dutch New Guinea up to 1942, when the Pacific War commenced. By focusing on educational practice, I demonstrate the entanglements between the Dutch East Indies administration, the Catholic mission and indigenous teachers in their need to ensure “civilized” subjects, disciplined labourers, and to modernize new generations by schooling children. Hence, the history of colonial education in South Dutch New Guinea offers a fruitful vantage point for exploring both the intertwinement of religion and governmentality in the Dutch colony and the multidimensionality of the colonial “civilizing mission” to which colonial education was paramount.

Throughout the colonial world, missionaries were pivotal in Western education. Sometimes, missionaries were the initial and exclusive agents providing colonial education to indigenous children. This has been noted in academic literature, where various scholars mention the importance of missionary education and its role in “civilizing” the Anglophone colonial world.Footnote 6 Through education, as Catherine Hall has argued, missionaries attempted to acculturate children to particular types of knowledge and conduct, so that they would “become people with particular kinds of selves, disciplined to be subject to others”.Footnote 7 Recently, as the introduction to this Special Theme highlights, scholars have tried to more precisely disentangle the complex dynamics between missions, state actors, and indigenous actors regarding education in the former empires during the colonial period. The historiography of colonial education in the Dutch East Indies, however, has centred on the state's development of colonial educational systems and policies.Footnote 8 Colonial education in the Dutch East Indies included public and private (confessional and non-confessional) schools that provided Western-style or popular education and were recognized (albeit with varying degrees of funding) by the state.Footnote 9 Such studies address mainly the region of Java, where the state vigorously expanded the colonial educational system and geared its education to children of the Javanese elite or mixed-race European children. The involvement of Christian missions with colonial education is often regarded as marginal in this historiography. Traditionally, the missions were thought to have derived from different motivations (convert indigenous people and establish the Church) and were not believed to invest heavily in “civilizing subjects”. Furthermore, this Java-centred focus led scholars to overlook the schooling of indigenous peoples in the Outer Provinces. Yet, precisely in these regions, colonial education was left entirely to private initiatives, such as the Protestant and Catholic missions. These institutions were embedded within colonial structures, whereby Dutch missionaries were important pillars of colonial rule.

Utilizing missionary records such as station diaries, letters, and articles that appeared in newspapers and MSC periodicals all kept at the archive of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus (Missionnaires du Sacré Coeur, MSC), this article addresses two phases regarding the education of Papuan children in South Dutch New Guinea from 1905 to 1942.Footnote 10 Focusing on colonial education practices, rather than on the systems and policies governing them, I interpret these missionary narratives by examining writers’ descriptions of and reflections upon their work. On this note, this article emphasizes that education catering to Papuan children in both phases went far beyond imparting new skills and knowledge. Indeed, the missionaries focused most strongly on regulating the conduct of their pupils. The mission was, as Ann Stoler would put it, deeply invested in the “tender microcosms” of indigenous children and youth, disciplining their bodies, minds, and beliefs according to Western Catholic standards to consolidate colonial power.Footnote 11 This article emphasizes that the missionaries’ transformational programme for educational and social reform among Papua's new generations was supported by the work of hundreds of non-European teachers, recruited from the Kei and Tanimbar Islands in southeast Maluku. Twenty-two translated and transcribed autobiographical accounts of these teachers are in the MSC archive, which I invoke to argue that they were important proponents of the “civilizing mission”, a fact rarely appreciated in the historiography of colonial education.Footnote 12

THE COLONIAL AND MISSIONARY PRESENCE IN SOUTH DUTCH NEW GUINEA

In the course of the nineteenth century, the Dutch state pursued a systematic campaign of appeasement, incorporating new islands and regions in their archipelagic empire. As one of the last regions, South Dutch New Guinea was placed under colonial rule with the establishment of a government post at Merauke in 1902, which was a colonial settlement rather than a Papuan village. Establishing this permanent colonial presence in South Dutch New Guinea was largely aimed at curtailing an imminent diplomatic crisis with the British administration over the headhunting activities of Dutch subjects (the Marind-anim). The tribe's violent incursions into the Morehead River area of British New Guinea had instigated an exodus of local peoples, leaving the area depopulated. The Marind-anim, known to the British as Tugeri, were notorious headhunters, who carried out frequent raids across their tribal borders. Obviously, the Marind were unaware that they were subjects of the Dutch colony, and that their raids eastward had targeted British subjects across a recently established international border.Footnote 13 While the Dutch administration issued an edict prohibiting headhunting, supported and occasionally enforced by military patrols on the British border, the colonial administrator (Assistent-Resident)Footnote 14 of South Dutch New Guinea, J. A. Kroesen, officially invited the Dutch Catholic missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus to “civilize” the Dutch subjects, with the objective of curtailing headhunting and other customs deemed problematic by the regime. Explicitly inviting a missionary presence into a colonized region was not common practice in the Dutch East Indies and marked the start of closer ties between the colonial government and the Catholic mission in South Dutch New Guinea.

These events were concurrent with the onset of a new colonial policy, the so-called Ethical Policy (Ethische Politiek). Changes in colonial policy around the turn of the century heralded what David Scott termed a modern form of colonial governmentality. Accordingly, colonial rule structures were characterized by “civilizing” colonial politics, which entailed collective regulation and improvements to the welfare of indigenous populations. Elsbeth Locher Scholten has convincingly argued that while the Ethical Policy has been largely framed in terms of modernization and humanitarian concern for Dutch colonial subjects, it coincided with violent territorial expansion and overall intensification of colonial interventions.Footnote 15 This is confirmed by the events in South Dutch New Guinea around the turn of the century.

Since the introduction of the Ethical Policy, the missions were heavily supported by the administration to implement the colonial education programme in the outer islands. Still, the Catholic and Protestant missions in Dutch New Guinea were geographically distinct. Protestant missionaries were active in the northern provinces of Dutch New Guinea and had settled the first permanent mission station on the Island of Mansinam (a small island off the coast of Manokwari) in 1855, long before any permanent government presence. Dutch Catholic missionaries, on the other hand, worked in the southern parts of Dutch New Guinea. This geographical division of mission fields resulted from the demarcation line drawn under Article 123 of Regeeringsreglement (of 1853 and later editions: roughly the constitution of the Dutch East Indies) by Governor A.W.F. Idenburg in 1912. While this line was abolished in 1927, when Catholic and Protestant missions opened schools and churches in competing territory, this division between the Protestant North and the Catholic South persisted long after decolonization.Footnote 16

Catholic missionaries who worked in South Dutch New Guinea were supported by the administration from the outset. Kroesen obtained a land allocation for a new mission station in Merauke and supplied building materials at no cost, as well convicts (kettingjongens) to assist with initial construction. The main mission station at Merauke was built 300 metres behind a series of army barracks in October 1905. The assistant-resident's support prompted Father Henricus Nollen to note his gratitude in the station diary.Footnote 17 In 1910, sixty kilometres (fifteen hours) north of Merauke in Okaba, a second main mission station was established. Three years earlier, the Okaba region had been “pacified” through military force, and a police post manned by twelve officers (Ambonese pradjoerits) opened there. Like the station in Merauke, this station in Okaba was built at the request and with the support of the assistant-resident. Between 1915 and 1922, the Okaba mission station was closed due to a lack of funding.

As both mission stations ultimately aimed to be self-sufficient, missionaries cultivated vegetables, raised livestock, and baked their own bread.Footnote 18 To secure additional funding, the Dutch MSC missionaries established a coconut plantation in Okaba in 1912. By the end of the 1920s, they expanded their plantation, buying several other plantations from the Kelapa-maatschappij, including the profitable enterprise Kolam-Kolam (near Sangasee). The plantation served a dual purpose: supplying the mission with much-needed income and providing an outlet for contact and potential conversions. Missionaries hoped the Marind workers they employed could be introduced to Christianity and persuaded to adopt the “Western” ethics of work and discipline.Footnote 19 With the coconut plantation, the missionaries operated within the economic context already present, as coconut plantations and (copra) trade were the Pacific model for colonial development.Footnote 20

The missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus were a Catholic congregation of brothers and priests.Footnote 21 Mission stations in South Dutch New Guinea usually consisted of two ordained priests and one religious lay brother living and working in a celibate community. Priests addressed the broad spectrum of spiritual needs among their flock, in addition to administration, financial management, and general operations of the mission station. Furthermore, they regularly left its confines to travel to Marind villages to conduct ethnographic and linguistic studies.Footnote 22 Meanwhile, missionary brothers worked around the mission station, farm, and plantation. As their own writings confirm, they were jack(s) of all trades and masters of none. Like other colonial settlers, the missionaries initially employed assistants from the Kei Islands to assist with manual labour.Footnote 23 This manner of outsourcing labour was necessary, because missionaries and other foreigners seldom succeeded in persuading Marind men to work for them voluntarily. This unwillingness is most likely because Marind boys and men were targeted for paid coolie jobs. Moreover, gendered divisions of labour in Marind culture qualified carrying loads as women's work.Footnote 24

Marind headhunting activity across the international border had declined from the outset of colonial and missionary activity in South Dutch New Guinea. As anthropologist Thomas Ernst suggested in 1979, however, internal factors were also significant in the declining incidences of border raids.Footnote 25 Indeed, the practice continued towards the hinterlands unsupervised by the administration; under assistant-residents R.L.A. Hellwig (1906–1910) and E. Kalff (1910–1912) refrained from intervening as long as Marind practices did not adversely affect settlers or colonial interests. In this regard, Father Jos van de Kolk spoke of a lack of humanitarian concern on the part of the colonial authorities, writing in the Okaba station diary that: “[No trouble] is the motto of the accommodating Administration […] as long as trade thrives. The colonial civilising imperative is not yet felt”.Footnote 26 In 1913, however, the newly appointed assistant-resident L.M.F. Plate sought to “appease” all villages along the coast. Intensifying colonial influence in the region demanded an extensive military campaign, whereby Marind were imprisoned and killed and their villages and boats burned. After this violent intervention, Plate intensified colonial control and appointed Marind village heads, imposed taxes (in the form of coconuts), and made Marind subject to corvée labour (heerendiensten).Footnote 27

The intensification of military and colonial control under the Ethical Policy resembles events in other parts of the outer islands, such as the Poso region in central Sulawesi.Footnote 28 Missionaries encouraged and praised the punitive subjugation of Marind peoples, rationalising violence as an inevitable (if regrettable) outcome of colonisation. As Remco Raben recently observed, a high tolerance of colonial violence in the Dutch East Indies underscored the missionaries’ evangelising mission.Footnote 29

MISSIONARY BOARDING SCHOOLS IN MERAUKE AND OKABA

The objective of converting Marind hearts and minds to Catholicism was at the heart of the South Dutch New Guinean mission.Footnote 30 Nonetheless, in the pioneer phase only a dozen or so baptisms were performed, most being children and adults in articulo mortis. In April 1912, Father Johannes van der Kooy wrote to his superior in the Netherlands: “I can say little about our evangelising work. If we whisk a soul into heaven every now and then, we can congratulate ourselves: no steady Christian congregation exists yet. We have six boys boarding in our house, but they may leave at any time”.Footnote 31 Indeed, as the diary shows, these boarders lived intermittently with the missionaries at the mission station.Footnote 32 Missionaries contrasted the obstacles they faced with their hopes for the new generation. For priests and brothers in South Dutch New Guinea, the mission's success was measured by the number of boarders they hosted, rather than by the number of baptisms they performed. Ten years later, however, the boys who took up residence with the missionaries would be their first Marind converts. These boarding school pupils received intensive extended education, so comprehensive as to be considered an “upbringing”, under the guidance of missionaries; only after completing this trajectory were they considered to be “civilized” enough to be eligible for baptism. The event occasioned South Dutch New Guinea's first ever baptismal festivity in 1922, marking the start of an indigenous Christian congregation in the region.Footnote 33

When the MSC missionaries established their Merauke post in 1905, priests set out to study Marind language and culture, soon encountering many aspects of Marind life that clashed with their Catholic beliefs and Western values. Headhunting, blood feuds, infanticide, physical abuse of women, vivisepulture, and sexual practices, notably the extramarital fertility ritual otiv bombari, caused consternation among missionaries.Footnote 34 They became convinced of the need for pre-conversion “civilization”: this more comprehensive process of cultural re-education should precede conversion and sustain the Catholic lifestyle thereafter. As Father Henricus Geurtjens wrote: “[T]hey should start by making these people decent, before they can think of making them Christians”.Footnote 35 Subsequently, the MSC missionaries became committed to the civilizing mission, which entailed a project to educate Marind children to transform the broader social milieu. From the perspective of the missionaries, Marind children were not yet totally “corrupted” and were consequently primed for conversion and “civilizing”. Education became essential to children's “civilization”, i.e. their acculturation to Catholic and Western types of knowledge and conduct.

Four years after their arrival, missionaries began implementing these ideas of educating children, establishing their first boarding school for young Marind boys in Merauke, followed by another in Okaba in 1913. In Okaba and Merauke, the school building and student dormitories were located in the mission station. Petrus Vertenten wrote about the school in Okaba to the MSC students in the Netherlands:

Our little school building, which had served as a storage site for all kinds of junk, boxes and copra for three years, was their first dormitory. Together, we built a house designed to accommodate twelve boys. They got old mosquito screens, blankets, clothing and tobacco.Footnote 36

Initially, only three to five boys were enrolled at the mission boarding schools. All boarders arrived voluntarily, a premise that the missionaries thought ideal.Footnote 37 Missionaries nevertheless encountered parents and relatives intent on persuading the boys to return to their native villages. For example, there was a child named Walwaw in Okaba, and Van de Kolk wrote: “As usual, the family came to reclaim the ‘defector.’ Walwaw's parents arrived in Okaba, weeping profusely”.Footnote 38 The same was the case with Bonek in Merauke, as Brother Gerardus Jeanson wrote: “[F]amily showed up regularly to encourage him to return to his village”.Footnote 39 Elders were suspicious of the educational intentions of missionaries and had little respect for schooling and upbringing outside the existing structures of family and society. They feared that adopting new ways of life would alienate their children from Marind customs and become a source of social discord.Footnote 40 Indeed, these were the intentions of the missionaries, who saw education of the children under their influence as a means of obliterating the barbaric traditions stemming from the Marind cult (religion).

As the educational programme set up by the missionaries did not conform to any official colonial models, the schools were not accredited by the administration, which did, however, support the mission financially by pledging five guilders per month, per student, from the local administration in Okaba and Merauke towards educating the children and maintaining their school.Footnote 41 Brothers and priests were involved in educating these boys. Priests taught catechism, basic literacy, and numeracy and lectured on geography, biology, Malay language and physics in the mornings. The lessons did not take place daily, however, as priests were constantly occupied by other tasks, such as their ethnographic activities and language studies outside the mission school. Outside the classroom, the boys assisted brothers in the gardens or the farm or on the coconut plantation. Brother Joosten, who was in charge of the farm and garden in Merauke (Figure 2), wrote about the boys: “When they were not in class, they had to work with me in the garden. Normally that was from eight till half past ten in the morning, sometimes till 11”.Footnote 42 This practical work was aimed at inculcating a Western work ethic and discipline, which missionaries thought would improve their moral character.Footnote 43 There were also pragmatic reasons for putting the pupils to work. Gardening and farming provided the missionaries and the boarders with grain, vegetables, and meat (essential commodities for feeding missionaries and boarders, especially in times of scarcity during World War I).Footnote 44

Figure 2. Brother Joosten MSC and some boarding pupils working in the garden at the Merauke mission station. Published in the missionary journal Annalen in 1910.

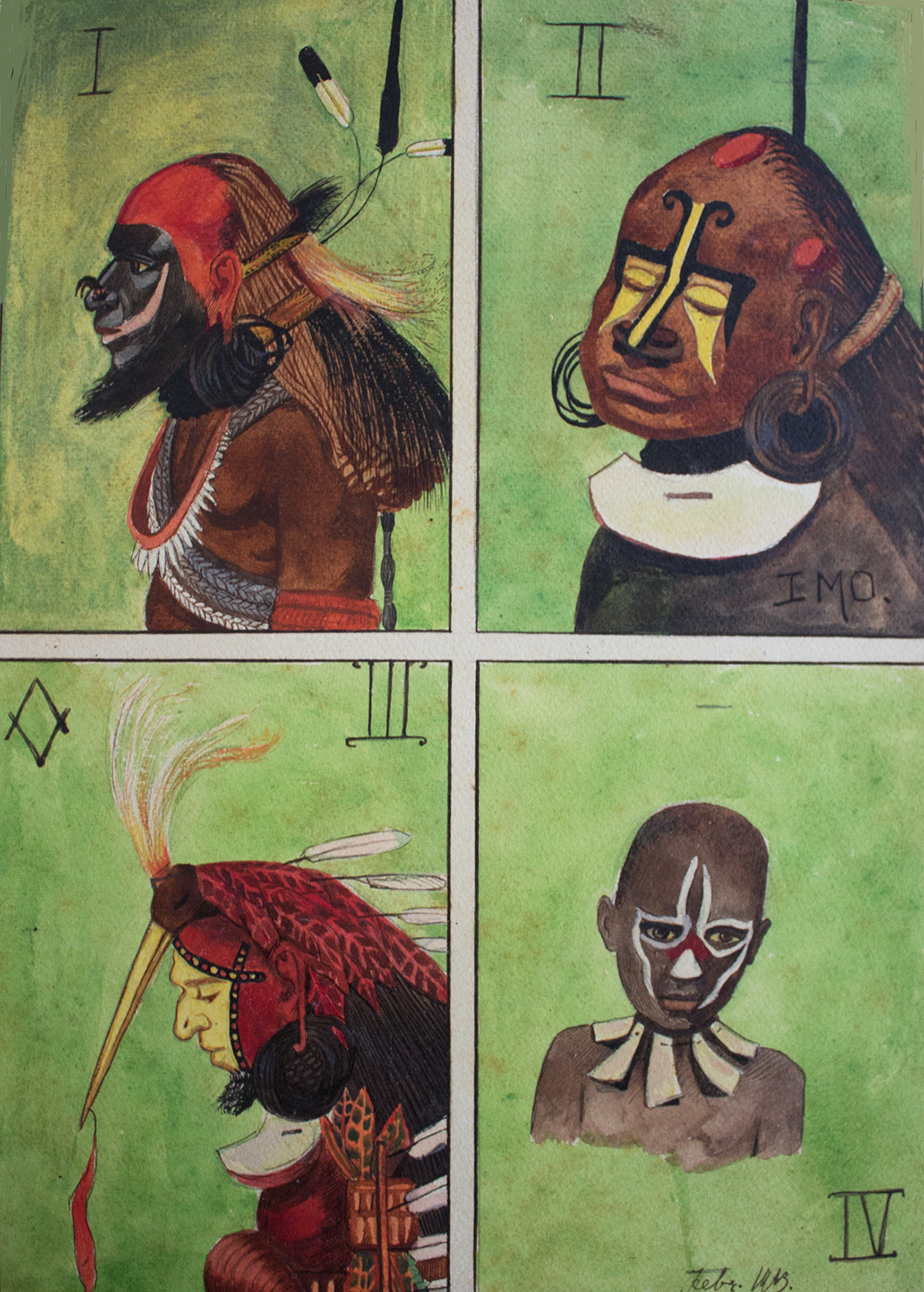

The boarding schools in Okaba and Merauke were based on a missionary policy of civilization through instruction. While not unique across the empire, this model was novel in South Dutch New Guinea and was aimed at providing the boys under missionary tutelage with a Catholic education. As such, the boarding schools were a means of destabilizing indigenous systems of knowledge and social organization, replacing them with an order of civilized, Christianized subjects who were eligible to convert to Catholicism. To break with indigenous practices, missionaries compelled their young boarders to eschew Marind dress (plaited hair, bodily paintings, and certain ornaments, Figure 3), donning plain fabric clothes in their place. Once pupils were admitted, they were required to adhere to a strict discipline and schedule, involving both schooling and practical work. While the missionaries tried to induce their pupils to adopt this new discipline and schedule (attending school, working in gardens, attending prayers and church, and eating new foods such as rice), the missionaries were unable to obliterate the Marind origins of their pupils. Consequently, they accommodated their desire for contact with kin and community, permitting them to visit relatives, attend certain feasts and celebrations and wear Marind ornaments underneath fabric clothes.Footnote 45

Figure 3. Marind dress. Paintings by missionary priest Petrus Vertenten, MSC.

Following the idea that a new, “civilized” generation had to be shaped and created by followers of Christ, the missionaries began acknowledging and facilitating “marriages” by young men in their care. While missionaries described these relationships as marriages, they were not registered, nor were Christian wedding ceremonies performed, because the grooms had not yet officially converted to Catholicism.Footnote 46 The first marriage of this kind was between Kenda and Jomar. Missionaries encouraged Jomar (the bride) to discard Marind dress and start wearing a sarong and kebaya, within a day. Brother Hamers had built the newlyweds a family dwelling on the mission station in Merauke. This domestic arrangement was uncommon for Marind.Footnote 47 Traditionally, men and boys occupied separate dwellings or “men's houses”, while women and children (including infant boys) lived in “women's houses”. When other Marind couples followed Jomar and Kenda's matrimonial example, missionaries considered establishing new villages with nuclear family housing.Footnote 48 As a small-scale pilot, two such villages were set up in Merauke and Okaba, offering Marind couples associated with the missionaries a chance to try living as a nuclear family. After 1921, these new villages became the preliminary design for a vast resettlement programme in South Dutch New Guinea.

“SOUTH NEW GUINEA IS DYING OUT”: THE RESCUE PLAN OF FATHER VERTENTEN

In 1919, Father Petrus Vertenten MSC wrote several alarming press reports on the possible extinction of the Marind-anim caused by the “corrupting” elements of their own culture, which appeared in newspapers in Java and the Netherlands.Footnote 49 While the trope of indigenous “extinction” was a dramatic rhetorical device often deployed by missionary writers, it was perceived by Father Petrus as a very real threat. First, the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918–19 reduced the Marind-anim adult population by twenty per cent. Second, Marind fertility had plummeted dramatically. In 1911, and again in 1915, missionaries already noted dwindling numbers of infants.Footnote 50 Missionaries argued that the low birth rate was due to infertility caused by granuloma venereum, also known as donovanosis. The affliction spread rapidly through Marind communities, especially through the Marind sexual customs and collective fertility rites (otiv bombari).Footnote 51 In 1953, researchers from the South Pacific Commission's aptly named “depopulation team” reported on the causes of depopulation among the Marind-anim in the 1910s and 20s, concluding that the coastal Marind-anim population had declined gradually from 10,000 to 5,000 in two decades. Maternal sterility was the primary cause. The frequent practice of otiv bombari, which intensified after the turn of the century in response to the social upheavals of colonization, were the cause, according to the depopulation team. Beyond transmitting infection, the physical rigours of group sex caused chronic vaginal irritation in women and chronic inflammation of the cervix uteri, both major contributors to infertility.Footnote 52

In response to the depopulation of South Dutch New Guinea, missionaries drew up a so-called rescue plan and lobbied the administration, promoting resettlement of “healthy” Marind in newly established villages as an expedient response to the crisis. The setting of these new villages, commonly referred to as model villages, was believed to free youngsters from traditional cultural obligations and sexual customs, such as the otiv bombari, thereby preventing the spread of the venereal granuloma. These model villages were also considered the basis for a healthier family life, crucial to new regimes of sexual discipline. This “healthier family life” was a nuclear family, centred on the married couple and their children living, sleeping, and eating together in a single dwelling. The ideal of monogamous, long-term cohabitation would, the missionaries believed, be the spiritual and moral salvation of the Marind-anim. Separate sleeping arrangements for husbands and wives under traditional domestic arrangements licenced the seclusion of boys and young men in the gotad (day dwellings), suspected hotbeds of homosexual activity by both the missionaries and the assistant-resident Plate alike.Footnote 53

In 1921, the proposed rescue plan, addressing indecent, immoral, and unhealthy customs among the Marind-anim, was accompanied by a complex set of coercive measures aimed at disciplining bodies. Medical treatment for cases of donovanosis was brought under stricter administrative control, and rites and feasts were widely prohibited to curtail otiv bombari. Furthermore, the model village policy radically and irrevocably altered traditional living arrangements of Marind (men's and women's houses), as well as their social lifestyles. Missionaries thus became pivotal in charting the domestic transformations, patterns of living, sleeping and being, which Margaret Jolly and Martha Macintyre also observed in the settler-colonial Pacific.Footnote 54

While the rescue plan of the missions initially advocated gradual resettlement of coastal Marind-anim in model kampongs, a policy programme was soon implemented, theoretically subjecting all Papuans from the newly opened areas to resettlement in nuclear-family houses, in the neatly ordered confines of model villages. This programme resembled the drastic changes introduced in Minahassan society, centred in North Sulawesi between 1830 and 1850. During this earlier period of colonial rule, the government closed traditional villages where inhabitants lived in long-houses, replacing them with smaller dwellings. This forced resettlement often compelled Minahassan families to adopt the nuclear model, seen by the administration as an essential precondition for organized cultivation of coffee and cacao for export.Footnote 55 The resettlement programme further eroded the autonomy of Papuans by reducing more expansive networks of kin into governable social units. Missionaries and colonial administrators alike regarded model villages as essential devices to this process.Footnote 56 Indeed, the model villages provided the administration with essential labour and taxes, in addition to affirming its colonial imperatives. Model villages were thus effective, multi-layered mechanisms for colonization, providing missionaries with more localized, interpersonal regimes of governance to realize their civilizing mission.

THE CENTRE OF CIVILIZATION: THE VILLAGE SCHOOL

During the first two decades of the colonial and missionary presence in South Dutch New Guinea, no formal educational system existed. Nor was education compulsory. With the introduction of the model villages in 1921, a formal colonial educational system was introduced via a policy based on Father Vertenten's rescue plan, termed “the five-year plan”. This marked the beginning of the expansion phase. Each model village was formed around a village school run by the mission. Children were required to attend this school, which would prepare them for Papua's emerging “modern” society. Subsequently, the mission expanded its sphere of influence substantially, resulting in perceived success in civilization and evangelization, measured in conversions and church attendance. As missionary Henricus Geurtjes wrote in 1925:

Nuclear-family housing was established for everyone along the coast up to Wamal […] Compulsory attendance brought all children into our schools, and that is how we placed all youngsters up to eighteen years of age under our influence on a regular basis […] We can say that […] the missionaries currently have all young people under their influence, and that the “younger generation” is quite receptive to good behaviour, which makes our missionary work here hopeful.Footnote 57

The first village schools opened in December 1921 in Merauke and Okaba, soon followed by Wendoe and Koembe. In 1924, the mission reported twelve village schools along the coast. Within ten years, the Catholic mission had established forty schools in model villages along the south coast of South Dutch New Guinea and a few in the hinterlands of South Dutch New Guinea. From the 1930s, the mission began opening schools in the hinterlands and western coastal areas.

With the onset of this rescue plan policy, the administration in Batavia arranged a special subsidy for the establishment of schools in model villages in South Dutch New Guinea. For a decade, the mission (teachers and pupils alike) had generous financial support from the administration, including construction of new school buildings. In 1931, this arrangement ended and all schools run by the mission were covered by the general subsidy regulation (the Algemeen Subsidie Reglement). Schools in the model villages thus had to meet the formal level and curriculum requirements for primary schools (dorpsscholen/dessascholen).Footnote 58 Meeting these requirements soon proved impossible.

The particular problems presented by formal colonial education in these parts of the Dutch empire prompted the introduction of a new and specific type of primary education for indigenous peoples in the Dutch East Indies, known as beschavingsscholen (civilization schools). These schools were more modest than regular village schools: the curriculum prioritized musical instruction (singing and playing the flute made out of bamboo), sports and games, and included unpaid manual labour, such as cleaning the courtyard and tending the school gardens. In these civilization schools, knowledge instruction (schoolse kennis) was limited to addition and subtraction up to one hundred, learning to read and write the Latin alphabet on slate and paper and Malay language instruction.Footnote 59

These beschavingsscholen and the accompanying subsidy regulations came into being in 1938, following a memo by assistant-resident Jan van Baal and a report by regional school inspector A.G.H. Wiggers.Footnote 60 In these new regulations, the administration acknowledged the contribution of the mission to the civilizing project. Individual beschavingsscholen could be upgraded to regular village schools, if the educational level of the pupils was high enough. In practice, the educational system for Papuans consisted of the schools in the villages, comprising civilization schools and village schools. The two types of primary schools, as well as the policy of tasking the missions with educating Papuans, were continued during the post-war colonial period.

In addition to establishing and managing village and civilization schools, MSC missionaries expanded the boarding school for boys in Merauke. In 1928, the FDNSC sisters (Filia Dominae Nostrae a Sacro Corde) opened a boarding school for girls in Merauke. This school accepted a few eligible Papuans and offered a choice between a vocational curriculum and the more enhanced Holland Inlandse School (HIS) curriculum (Figure 4).Footnote 61

Figure 4. Schoolchildren trained in carpentry in Merauke.

The Catholic mission established the colonial education system in South Dutch New Guinea as a project carried out in conjunction with the colonial government. The administration granted material and financial support for the schools, but also introduced the policy of village formation (model villages), giving the mission the space to open schools. The schools, however, were run by the MSC missionaries, specifically by a priest delegated as school administrator (schoolbeheerder). Nevertheless, these schools could not operate without teachers. As the very few missionaries were already assigned other tasks, non-European teachers from elsewhere in the Dutch colony (especially the Kei and Tanimbar islands) were employed at these schools.

EDUCATORS OF PAPUAN YOUTH: NON-EUROPEAN TEACHER FAMILIES

Missionaries were convinced (according to contemporary pedagogical theory) that children's minds and behaviour developed via observation and imitation. Papuan children therefore needed “good”, Catholic, “civilised” teachers as role models. The dozen or so missionaries stationed at the several mission posts scattered around South Dutch New Guinea were the obvious candidates, but they numbered too few to man all the schools in the newly established and rapidly expanding model villages. So, missionaries came up with the plan to deploy Catholic teacher families educated at the mission's boarding schools in Langgur to the Kei Islands, which had supplied non-European teacher families for the village schools in Kei and Tanimbar since the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote 62 The missionaries intended for Keiese and Tanimbarese teacher families to serve as models of a “modern” Catholic family, instilling a “modern” Catholic way of life in the “more inferior” Papuans and, consequently, the Catholic faith. With the deployment of these non-European teacher families, as argued above, a dual colonial system was cultivated in Dutch New Guinea, in which the Keiese and Tanimbarese teachers functioned as intermediaries.Footnote 63

Movement of these teacher families between different parts of the Dutch empire demonstrates the investment in human resources underpinning the educational project, as well as missionary prejudice towards and racial ranking of Papuans and other indigenous peoples in the Dutch colony. Papuans in general were not perceived by the missionaries as suitable candidates to become teachers or role models, in part because of their inferior racial status. Nor was an educational trajectory in place in South Dutch New Guinea enabling Papuans to become teachers. In 1939, anthropologist and Governor Jan van Baal wrote that he considered it impossible that, in the coming twenty-five years, Papuans would be trained as teachers. He was mistaken. Not because he made a poor assessment, but because he simply could not predict the impact of the Pacific War,Footnote 64 during which large parts of Asia and the Dutch East Indies were occupied by Japan. While South Dutch New Guinea remained unoccupied, ties with the rest of the colony were severed and the supply of new teacher families from the Kei and Tanimbar islands was interrupted. Consequently, missionaries were compelled to train Papuans (from the Muju area) as teachers.Footnote 65 After the war ended, missionaries launched a teacher training programme in Merauke. One of the first Papuans to be trained as a teacher was Paulus Keji, who started to work as a guru in 1951.Footnote 66

The first two Keiese teacher families arrived in November 1921. They were employed at the schools in the model villages of Merauke and Okaba (Figure 5). Soon, many more non-European teacher families (mostly Keiese and Tanimbarese) were deployed by the mission to work in the rapidly expanding village schools. The teacher, who was salaried (Guru or Bapak), his wife (Njora or Ibu) and eventually their children would inhabit a house next to the school in the model village. In some instances, these villages with houses and a school had already been built. In other cases, especially when “new areas” were opened, the guru and the njora had to arrange the establishment of the model village, including instructing Papuans to build family houses and the school. Njora Werenditi, who together with her husband was employed in the Upper Digul/ Mappi area, remembers that upon their arrival in 1937:

[T]here were no decent houses. So, the guru [my husband] arranged kampong housing. There were houses, but they were not neat. So we built a new village. Everyone had to build a new house of his own and live separately.Footnote 67

Figure 5. Two schools boys and teacher, Merauke, ca. 1935.

Eduardus Ulukjanan, who worked on Komolom, and Amandus Letsoin, who worked on Kimaam, in the 1930s not only had to build the school, but also had to attract students:

Initially, the schoolchildren did not want to attend school. “What should I do about that?” I asked the kepala kampong. He said, “Bapak must not hit them, but do you have fish hooks and table salt?” I said, “Yes, I do.” “Well, give them to me, and I will give them to their parents.” Well then I gave those fish hooks and salt to the kepala kampong, and he gathered the people and told them the children needed to go to school. […] They came the next day.Footnote 68

The other interviews with gurus, their wives, or their children in the archive also show that fish hooks, tobacco, and knives were used as goods to convince children to attend school.Footnote 69 Jan van Baal indicates that when a school was eventually established, school absenteeism was rarely a problem.Footnote 70

At school, non-European teachers taught the Papuan children basic educational and practical skills. The children were taught the basics of Malay language, reading, writing, and arithmetic. Guru Amandus Letsoin recalled:

Two times two, we did that using a blade of grass or just our fingers. So, two times two, they had to count that over; one, two, three, four. That was not very hard […] Reading, however, was very challenging. If you told them to read a book or [read] from the blackboard, then they were really struggling.Footnote 71

Njora Werenditi recalled that, during the first few years of the expansion phase, teaching and communicating was done in the Marind vernacular.Footnote 72 How fascinating this is: the missionaries who inspired the transition from oral to written language with their language studies during the pioneer phase.Footnote 73

When the mission expanded beyond Marind territory, where the missionaries encountered a mosaic of many different ethno-linguistic groups, Malay was introduced as the language of instruction at schools. While this opened up the possibility of circulating teachers between schools, it presented a problem for non-European teacher families. They now had to teach the children a new language. To add a more practical dimension to this Malay language instruction, gurus wrote instructions on the blackboard, after which they took the children to the forest to start learning the words of the things they encountered.Footnote 74 Jan van Baal indicated that because instruction was in Malay, progress was very slow. On his experience at a school in Upper Bian, Van Baal wrote: “the first class could add and subtract up to six, the second class up to thirteen, and the third up to twenty”.Footnote 75

While non-European teachers were expected to provide basic instruction in reading, writing, and counting, school above all had to train young Papuan children in good behaviour and Christian values, qualities they were unlikely to encounter in their homes or learn from their parents. As such, school was seen as the centre of civilization and the teacher families, thereby, as “civilizers”. Markus Fofid remembers that gurus and njoras were “real educators, real fathers [and mothers, MD] for the Papuan children”.Footnote 76 To this end, music, sports, and manual labour were part of the school curriculum. While horticulture was not a mandatory school subject before the beschavingsscholen opened in 1938, working in the garden always figured in the curriculum offered by teacher families.Footnote 77 Marcus Fofid, the son of a couple who came to work in South Dutch New Guinea in the 1930s, recalled:

The school garden had many different functions. The first was to provide for the needs of the school and the children. Especially when the children were under the care of the teacher families, and their parents did not bring any food, we had to gather the food from the school garden for the pupils and the guru and his family. The garden was planted by the children and was thus [used] for more than food.Footnote 78

Like the mission station garden during the pioneer phase, the school garden also served to instil work discipline (Figure 6). As Ibu Tuyu stated: “that garden was there just for teaching children to work”.Footnote 79 In 1934, all teachers received an instruction booklet from the missionaries comprising directions for tending the school garden. Njora Werenditi remembered that her husband taught “school in the garden: he chose a day from the lists the priest had given him and scheduled school in the garden: loosen the soil, cleaning, etc”.Footnote 80 In the school garden, missionaries cultivated various kinds of foods and vegetables that were new to Papuan children. As such, ubi, rice, potatoes, corn, kasbi, and keladi became part of a new diet. The teachers were allocated at least half the harvest.Footnote 81 Some of the teachers’ families also planted ceiba trees for kapok fibres. These were used to spin and weave thread for the girls and the njoras (the teachers’ wives) to make clothes.Footnote 82 While labour and schooling coexisted in the everyday lives of Papuan children, the role of labouring for the family (in the family gardens) in the children's lives has yet to be investigated.

Figure 6. School garden in Wendoe.

While the gurus performed their duties inside the classroom, where they taught both boys and girls, njoras were supposed to teach Papuan girls outside school hours, instructing them in cleaning, cooking, and washing. Paulus Kaiji, once a Papuan schoolboy, remembers that: “the njora prepared food for boys and girls, and she was always there for us. […] mama taught the girls to cook, fry sago, cook rice and other stuff”.Footnote 83Njora Werenditi, who came from Tanimbar to South Dutch New Guinea, also taught Papuan girls handicrafts and needlework, as did the other teachers’ wives. “I taught them to make strainers for sieving and winnowing or bags to store their barrang [stuff] and clothes, yes I also taught them to spin and weave kain [sarong cloth], Tanimbar kains”, Njora Werenditi explained.Footnote 84

Catholic religious instruction, holidays, and ritual items were key in transmitting knowledge and cultivating new practices. Each school day began with making the sign of the cross. The Ten Commandments and various prayers had to be memorized and, every week, the children were told to learn a new story from the Bible. Reciting, memorizing, and reading these religious stories increased the children's Malay vocabulary while at the same time teaching them punctuation and morals and enriched their spirits. The guru and njoras were also expected to prepare the children for Catholic holidays, such as Christmas, Easter, and annual baptism celebrations (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Easter celebration in the model village of Bofagage, middle Fly region.

This included dancing and musical (singing and playing the flute) instruction, with the intention of replacing the “uncivilized” sounds and dances of Papuans with more sophisticated expressions. Guru Fanghoi describes his experience teaching the children to play the flute, which the teachers made themselves from bamboo:

They greatly enjoyed producing sounds; in the beginning the adults were not too happy: they considered it foolish and were reminded of the buzzing of the swinging batons of the secret cult […]. At first, the elderly sometimes destroyed the flutes, […] and I had to make new ones the next day. Gradually, they stopped taking offence and fearing that the children were getting into trouble.Footnote 85

The flute orchestras, in which the schoolchildren took part, were a common sight since the arrival of teacher families. The flute orchestra was the pride of the village.Footnote 86

In accordance with their “civilizing” mandate, non-European teachers were expected to encourage wearing Indies/Western-style clothing and new standards of hygiene. This was one of the first tasks of gurus, once they started working. Njora Tuyu, who came with her parents to Koembe, in the Merauke region in 1923, recalls:

On a certain Sunday he [my father the guru] gathered all the children in our house and instructed them to wash. When they returned, he gave them all clothes, and mama [my mother], had to teach them how to wear the sarong. The little ones received some shorts with a piece of string, back then we did not have elastic. In any case, they were not allowed to run around naked anymore.Footnote 87

Children who attended school and church were given trousers and sarongs, and the older men and women were encouraged by the guru families to wear clothes made of fabric. Ibu Somar, who was employed in a village at the Kumbe River with her husband in 1930, remembers:

The [Marind] people were still attached to their adornments [ornaments made of pork, plaited hair, body paintings]. Slowly they followed our example. We taught them to pray and gave [them] religious instruction, telling them “if you want to pray, you have to get discard your garnish and dress properly. That's what we do too! […] Step by step, they started to abandon their traditional dress. I cut their hair and threw it away as far as I could, after which I gave them a dress. A beautiful kain for the schoolchildren, […] and for the men a pair of trousers and a shirt.Footnote 88

These fabric clothes, distributed by the guru families, were obtained via a variety of methods. Some clothes were given by the priests, who got them from fundraisers. In other cases, gurus sold produce from the (school) gardens and bought the clothes in Merauke or Tanah Merah, while other teacher families made clothes together with the pupils by hand.

MISSIONARIES’ EDUCATIONAL PROJECT AND THE CIVILIZING MISSION

In this article, I have explored the history of colonial education in South Dutch New Guinea, stressing the diversity of actors in the colonial educational landscape, as well as the local educational practices involving indigenous children. This approach complements existing scholarship on colonial education, which focuses mainly on governmental policies on colonial education. In addition, I have added to the historiography by showing that through education, non-European (i.e. indigenous) and non-state actors were also an integral part of the colonial state's civilizing project.

In South Dutch New Guinea, Dutch missionaries had a privileged position as the sole providers of Western education. This contrasts with other early twentieth-century European colonies and parts of the Dutch East Indies, where the colonial authorities provided Western education for indigenous children. While schools were a means to convert Papuan children, they were also pivotal in a programme geared towards “civilizing” and modernizing new generations of Papuans. During both phases, the emphasis of the education was less on acquiring religious and other knowledge than on character building and broader acquisition of the symbolic and material trappings of “civilization”. As such, civilizing went hand in hand with education just as Catholicism and modernity were two sides of the same coin.Footnote 89 Hence, through these educational initiatives, both missionaries and indigenous teachers became closely involved in the colonial civilizing mission. At school, children were acculturated to particular ways of being. Their conduct was regulated by subjecting their bodies to new educational practices, domestic arrangements, styles of dress, Western hygiene, and a strong work ethic. The aim of reforming the Papuan domestic sphere and society even gave rise to a specific type of colonial education: the beschavingsscholen. These educational practices reveal, on the one hand, the underlying objective of the “civilizing” school: empowering, “civilizing”, and converting Papuan children.Footnote 90 On the other hand, it shows that educational actors in South Dutch New Guinea used unpaid child labour to instil discipline, as well as to obtain the requisite supplies and income.

The scope of the educational project and the “civilizing mission” in South Dutch New Guinea relied heavily on those non-European teachers. Teacher families from Kei and Tanimbar settled permanently in the model villages and accepted employment in the mission schools. They were convinced that Papuans were in need of development and that Papuan children needed disciplining. These teacher families instructed the Papuan children and interacted with their parents daily (more often than the priest who visited the villages sporadically), were messengers and executors of the mission-imposed reforms relating to its civilizing project and were pivotal in the emerging indigenous Catholic community. The involvement of these non-European teachers, drawn from elsewhere in the colony, highlights the ambiguities of colonial education projects and broader “civilizing missions”.