1. INTRODUCTION

China has copious quantities of disputation, contention, and strife. But it also has long nurtured special institutions designed to mitigate social conflict. One such institution—people’s mediation committees (renmin tiaojie weiyuanhui, 人民调解委员会)—has been a particular focus of academic curiosity and debate. These committees have a vast presence; they numbered 798,000 as of 2015,Footnote 1 manifested primarily in the ultra-local governance bodies known as Residents’ Committees (RCs, jumin weiyuanhui, 居民委员会) in cities and Villagers’ Committees (VCs, cunmin weiyuanhui, 村民委员会) in the countryside. This article follows up on earlier research that examined mediation of actual civil disputes in both urban and rural settings.Footnote 2 But here we focus on mediation specifically in villages—where it is most prevalent.

The ever-resourceful Chinese state has developed new institutions and practices for coping with conflict, particularly for “maintaining stability” (weiwen, 维稳) in the face of collective protests. A few scholars have delved into these processes, giving insights into the ways in which officials negotiate with protesters using a toolkit of carrots, sticks, and psychological techniques, and decide whether to repress collective resistance or to make concessions.Footnote 3 The emphasis has been on events that most threaten the political order: group protests that directly target or implicate the state itself. Here, by contrast, we focus on more ordinary conflicts that take place between citizens. We are looking at “normal” state-society interactions rather than crisis management.

There are two primary motivations for our study. First, the work of village mediators provides a window into an important aspect of the state-society relationship. Villages, of course, are an essential hub where imperatives and administrative programmes from higher levels of the party-state connect with the rural population through the institutions of the VC and the village party committee. Cadres at this level implement a range of policies and make decisions concerning essential resources such as land and the maintenance of infrastructure such as roads and schools. The mediation of disputes fits into a web of practices through which power-holders exercise and demonstrate their authority. While it may seem peripheral at first glance, in fact it can be quite an important part of a village leader’s duties. For example, in Peter Seybolt’s oral history of a Henan village, the party secretary noted that resolving serious disputes (over issues such as theft and residential property lines) came second only to birth control on his task list.Footnote 4 Indeed, in the localities we surveyed, 89% of village leaders reported spending time mediating disputes among villagers. Dealing with such conflicts ranked fourth on a list of tasks that preoccupied village heads and party secretaries, well ahead of duties such as overseeing collective enterprises, providing for public safety, and sorting out disputes between villagers and the government.Footnote 5

This paper thus helps to clarify the role played by village cadres (as well as other potential sources of dispute resolution, both within and “above” the village) in addressing conflict. The over-time data generated by our repeated survey sheds light on how this role is changing. One could imagine that the role of local cadres in dispensing justice might have strengthened or at least remained steady between 2002 and 2010. During Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao’s leadership—which basically corresponds to the interval between our two surveys—the party recommitted itself to resolving rural problems through new policies aimed at building a “new socialist countryside.”Footnote 6 Also, as we know, the party-state placed great emphasis on maintaining stability; local cadres came under pressure to reduce conflict, resolve problems, and stop petitioning, litigation, and mass incidents.Footnote 7 All this would give village authorities more reason to intervene in disputes and more incentives for ordinary people to take disputes to village cadres. One might call this the “resilient village justice” hypothesis. Alternatively, a “modernization” perspective would predict that this role would have weakened over time. In the wake of the state’s abolition of agricultural taxes, village leaders may have less motivation to attend to residents’ everyday troubles.Footnote 8 As (at least in part) a legacy of the Maoist past, perhaps mediation is fading as time passes. With economic development and improvements to institutions at the township and county levels, villagers might be expected to turn to more formal forms of dispute resolution, such as lawyers, courts, or other state judicial agencies.Footnote 9

Grassroots mediation is also of interest in and of itself, and ongoing debates about this practice constitute a second impetus for this article. Local mediation in China has attracted curiosity and scholarly attention for generations, dating back nearly five decades, if not longer, to Lubman’s “Mao and Mediation.”Footnote 10 Numerous articles are premised on, or at least explore, the prospect that China’s local practices for handling disputes might provide a low-cost and humane alternative to formal institutions such as courts,Footnote 11 and some also assert that these practices have roots in China’s ancient past.Footnote 12 Thus, people’s mediation might serve as a positive example of “alternative dispute resolution.” Yet this benign perspective is not the only way to look at mediation. Researchers like Lee and Zhang, for example, justifiably include it among processes used by city agencies to tamp down, depoliticize, and institutionalize protests by citizens with legitimate grievances.Footnote 13 And, as noted below, others have questioned whether it actually happens and serves any real purpose. Thus, we continue lines of inquiry that extend far back in time and involve sharp differences of perspective.

A renewed emphasis on mediation within China’s political and legal system figures heavily in the recent debate about whether China has taken a “turn away from law”Footnote 14 perhaps toward “authoritarian populist justice.”Footnote 15 This discussion has focused less on people’s mediation and more on judicial mediation (in which courts and judges shepherd litigants toward a negotiated resolution) and grand mediation (in which party or government authorities oversee negotiations over land seizures, labour unrest, or other large-scale conflicts).Footnote 16 Important as these higher-level types of mediation are, the majority of China’s mediation happens outside of the judicial context. According to official figures, the number of cases handled through people’s mediation committees in 2015 was about 3.4 times the number of first-instance civil cases concluded through judicial mediation, and this ratio is virtually the same as it was in 2002 and 2010 (3.5 in both years) when we collected our survey data.Footnote 17 Quotidian but widespread, grassroots mediation also deserves study to determine how effective it is, who uses it, and what kinds of disputes are brought to mediators.

China’s party-state certainly believes that mediation is important. Dispute resolution is one of the explicit tasks given to RCs and VCs since their inception in the 1950s and, to this day, individuals within these committees are designated as leaders or members of subcommittees responsible for mediation. They write regular reports on their labours that feed into official statistics. Thus, in 2015, China’s 3,911,000 people’s mediators were said to have mediated 9,331,000 civil disputes (minjian jiufen, 民间纠纷)—slightly more than double their 2006 output. Over these nine years, the average number of cases per committee jumped from 5.5 to 11.7—an impressive boost in productivity, it would seem.Footnote 18 Local governments as well as national authorities typically claim higher than 90% success rates for mediators, and even assert that their efforts avert tens of thousands of suicides and crimes every year.Footnote 19 These official accounts and figures convey the notion that people’s mediation is not only extraordinarily effective, but also is a tidy process that can be neatly summarized. Academic studies routinely cite these official figures, despite their questionable validity. We believe, as discussed below, that studying mediation through non-state sources is superior for the purpose of understanding how this institution works in practice.

In this paper, we draw on new data to extend and update previous research that addressed a number of issues concerning mediation.Footnote 20 Our earlier work drew on 14 months of ethnographic research in ten Beijing neighbourhoods, together with a survey of Beijing residents and another survey of villagers in six provinces (more on which below). This empirical basis informed several aspects of our perspective on mediation, as follows. The first concerns the nature of mediation itself. Contrary to the cut-and-dried impression conveyed by official figures, mediation is in fact a messy and complex practice. A given instance may not even be thought of as “mediation” by all participants. It is not generally initiated by mediators themselves, contrary to some portrayals.Footnote 21 Rather, it typically results from one party in a conflict asking local authorities to intervene on their side and give them leverage against their adversaries; thus it starts “from below.” It is not only members of a mediation committee that might get involved in a particular dispute, but also other village or neighbourhood cadres who happen to know the parties or have knowledge of the situation. It also need not be a one-time event. Disputes often simmer for months or years, local authorities might intervene repeatedly, and a resolution might be reached at one point, only to unravel later.

More generally, people’s mediation must be put in context in several ways. One way concerns power relationships in the neighbourhood and village. RCs and VCs do not generally have the capacity to coercively impose a settlement on quarrelling parties, yet their official status, their mandate to cope with trouble, and sometimes the position of respect enjoyed by their leaders give them a certain amount of persuasive clout. Playing the role of peacemaker helps them enact their authority in the neighbourhood or village. The personal dimension of mediation—the fact that the mediator him or herself is embedded in the community social structure, together with the parties themselves—means that the social roles and backgrounds of everyone involved are likely to shape the process and outcomes of disputes. As discussed later in this paper, status- and class-related factors often play a role.

Furthermore, citizens embroiled in disputes have multiple places they can go and multiple potential allies to enlist on their side. Neighbourhood or village leaders are one possible source of help, but so are (for instance) relatives, elders, or other persons who have stature in the locality, people with connections to the other party in the dispute, as well as the police and offices of higher levels of government, notably the street office (in cities) or township (in the countryside). “People’s mediation” is just one possibility out of many.

A specific point of scholarly controversy has been the issue of how prevalent community intervention in disputes actually is in Chinese society. James A. Wall, Jr and Michael Blum once portrayed mediation as omnipresent in China, taking place at the drop of a hat, and posited that this resulted from cultural and historical traditions.Footnote 22 Neil Diamant challenged this position and suggested that mediation was instead rare and perhaps even illusory, drawing on archives from the 1950s and 1960s as well as other sources.Footnote 23 In an effort to adjudicate this matter, we found that:

In major cities, or at least in Beijing, mediation is relatively rare, yet it unmistakably remains a resource that ordinary people turn to in certain types of conflicts, particularly those involving neighbours. In the countryside, our data suggest, it is comparatively common for individuals to ask the Villagers’ Committee for help in sorting out altercations. Rural people seek VC intervention on a substantially wider range of problems as compared to their urban counterparts, even as they also address conflict through a resourceful variety of other channels.Footnote 24

The task of understanding mediation’s actual role remains vital today. With an eye to the intrinsic importance of this institution as well as the light that it sheds on local state-society relations, we update our previous analysis with data from a follow-up survey conducted in 2010. We revisit the questions that we previously addressed, particularly focusing on: (1) the incidence of mediation—that is, what fraction of the population experiences it; (2) how different types of disputes vary with regard to how often village-level mediation, as opposed to other sources of help, is sought; (3) how citizens from different socioeconomic status categories, and in different villages, vary in their disputing behaviour; and (4) whether people assess their experiences with village mediation favourably or unfavourably, in comparison with other means of seeking redress. The next section explains our methods and data sources. We then lay out our findings, and close by offering conclusions about continuity and change in mediation over time.

2. METHODS AND SURVEYS

As the previous section made clear, mediation is not a simple thing to study. Approaches that rely on state sources or state agents (e.g. interviews with mediators or statistics based on their reports) have limitations and can be prone to the kinds of biases that afflict any process that states see as something to boast about. Our method sidesteps these problems by avoiding the state and its records altogether. Instead, it relies on information provided by ordinary citizens in response to survey questions concerning disputes that they have encountered. In this way, we build an understanding of people’s mediation from the people’s perspective—from the ground up. In so doing, we compare mediation with the various other ways in which villagers seek recourse when dealing with disputes.

The surveys used to implement this approach were designed and organized by the second author in collaboration with sociologists of Renmin University of China, particularly Guo Xinghua, Lu Yilong, and Feng Shizheng. The 2002 survey resulted in responses from some 2,970 households in six counties: one county in each of five provinces (Henan, Hunan, Jiangsu, Shaanxi, and Shandong) and one provincial-level city (Chongqing). The counties were selected purposively, not randomly, with the goal of obtaining wide variation in socioeconomic contexts. Our findings thus cannot necessarily be taken as representative of all of rural China, but are nonetheless based on a broad range of settings in the Chinese countryside, including both wealthy and poor regions. One township was selected in each county; four or five villages were chosen in each township. Interviewers were trained to choose households randomly within each village, and respondents randomly within households. The 2010 follow-up survey included the same sites except those in Shandong. Only places covered in both surveys are employed in the analysis that follows. Thus, this paper is based on data from 23 villages in five provincial-level areas, including 2,164 respondents in 2002 and 2,659 in 2010.

To be clear, this was not a panel study; the random sample of respondents drawn from each village in 2010 was not the same sample that was drawn in 2002. Still, the design has distinct advantages in drawing respondents from the same villages in both years. Any differences (or lack of differences) between the two surveys should have much more credibility than if a new sample of villages had been selected the second time around—they cannot simply result from accidents of village selection.

At the heart of both surveys lies a battery of questions concerning as many as 20 different types of disputes: conflicts over debts, employment, goods purchased from businesses, and personal injuries, as well as tiffs with neighbours and disagreements within one’s own family. For purposes of this article, we selected only disputes that were likely to have involved the respondent’s fellow villagers as adversaries, as opposed to the village leadership itself. The latter, while important in their own right for understanding contention in the countryside, are not suitable for exploring village authorities’ role as a third-party mediator of conflicts among residents. Thus, we focus on civil (i.e. citizen-vs.-citizen) disputes and exclude those whose topics centrally concerned areas of village authority.Footnote 25 The topics were: land for homes; water use; debt; consumer issues (dealings with businesses); divorceFootnote 26 ; neighbours; labour; disputes within one’s own family; personal injury; property damage or loss; and accusations of personal injury or theft. In the tables, some of these 11 dispute types are combined to form eight categories.Footnote 27

For each type of dispute, respondents were asked whether they or their families had been involved in such a dispute during the previous five years. They were then asked about any “individuals or agencies” (geren huo bumen, 个人或部门), namely third parties, they had gone to for help in those disputes. The questionnaire did not suggest any specific names or categories of third parties to the respondents; these open-ended questions left it up to them to explain, in their own terms, from whom they had sought help.

The survey also contained a separate set of questions specifically about interaction with and perceptions of the Villagers’ Committee. In these closed-ended, yes/no questions, survey-takers were asked whether they (as individuals) had ever sought the VC for various reasons. Among these reasons were two specific kinds of disputes: one involving neighbours and one within the family, such as between spouses or between a mother-in-law and a daughter-in-law.Footnote 28

3. FINDINGS

3.1 Incidence of Mediation

How often mediation takes place is one of the essential questions surrounding it. Is mediation by village authorities a practice that has fallen into disuse—or one that remains common? Indeed, the disagreement between Wall and Blum (on the one hand) and Diamant (on the other) turned on whether mediation took place regularly or was chimerical. As noted previously, mediation is not a single, clear-cut thing. Efforts to measure it, especially measures that span large numbers of localities and people, can only be partial. The two types of questions in our surveys therefore each provides a different perspective.

One way of posing the question of the frequency of mediation is: what percentage of the adult population in rural China has sought mediation? Table 1 presents answers to this, drawing on data first from the closed-ended questions, then from the open-ended questions. In the 2002 survey, 17% of respondents reported having ever taken a neighbour dispute or a within-family dispute to the VC, while only about 10% did so in 2010. In part, this may reflect the declining prevalence of these two particular kinds of dispute. Neighbour disputes and within-family disputes both appeared more frequently in 2002 than in 2010. As well, the batteries of questions that included these measures found that respondents reported seeking out the members of their VC for various purposes (to discuss fees, documents, security, family planning, and so forth) fewer times in 2010 as compared to 2002. Thus, having had less reason in general to interact with community leaders, respondents in the second survey were also less likely to report seeking their assistance with these two specific types of trouble.

Table 1 Incidence of requests for mediation: various types, measures

Note: 2,164 respondents in 2002; 2,659 respondents in 2010.

The open-ended questions about disputing also found a declining incidence of village mediation. Here, the range of possible disputes was much wider, including all 11 forms of citizen-vs.-citizen conflict that appeared on both surveys. The timeframe was limited, however, to disputes that took place “in the past five years.” In 2002, 8% of respondents reported having sought help from village authorities for at least one such dispute; in 2010, only 5% of respondents said the same thing. All told, combining the various questions into a single measure, the 2010 survey found a considerably lower incidence of mediation than its predecessor did. Only 12% of respondents reported any experience with village mediation, as opposed to 22% in the 2002 study.

Why the lower incidence of mediation in 2010 relative to 2002? The major reason is that there were fewer citizen-vs.-citizen disputes. Survey-takers reported a household average of 1.25 citizen-vs.-citizen disputes each in 2002 and only 0.64 in 2010—a 49% decline. It is important to note that this comparison overstates the decline in disputing, because it holds the topics of contention constant, whereas to some extent villagers were arguing over new and different things in 2010.Footnote 29 Still, reported disputes per respondent clearly declined, and this is not a result of panel conditioning.Footnote 30 Why, then, were there fewer disputes? We can offer no certain explanation. Possibly, this results from the gradual resolution of issues that had previously been in flux due to social and economic change, or from the state’s efforts to tamp down rural conflicts of all kinds. Another possible cause is outmigration from villages. The proportion of villagers reported as “working outside the village on a long-term basis” increased by 86% between the two surveys, and the proportion of households with any members working outside the village, whether short-term or long-term, increased by half. Outmigration could mean fewer pressures and conflicts within a given village.Footnote 31

It should be noted that both the 2002 and the 2010 figures likely understate the actual incidence of mediation. The surveys could not cover every possible type of dispute, and our omission of categories of dispute that might involve the VC itself as a party was conservative. Also, neither survey was designed to capture people’s participation in mediation that was initiated by others (i.e. by respondents’ opponents in disputes) or by the village authorities themselves. Thus, these figures should be treated as a rock-bottom, verifiable minimum, bearing in mind that the total incidence is likely quite a bit higher.

Do men and women use mediation differently? We looked carefully for gender differentials in the data. By some measures, men reported having sought village-level help in disputes at slightly higher rates than women, yet in only one case did these differences meet a standard test of statistical significance.Footnote 32 Men and women alike draw upon grassroots mediation, though the possibility that men are at least marginally more likely to avail themselves of such assistance bears continued scrutiny.

3.2 Pathways Pursued in the Course of a Dispute

Here we shift from thinking about “what proportion of the population has experienced VC mediation” to considering “when a dispute happens, how likely is it to be taken to village authorities for mediation?” One of the distinctive strengths of the surveys is that they inquired about a range of possible trajectories that a given dispute could take, and thus allows us to consider village-level mediation in comparison with other possible outcomes. They also collected information about many kinds of disputes, allowing comparison across categories. Table 2 gives an overview of data from the surveys across these two dimensions: dispute trajectory (left to right) and dispute type (top to bottom). The purpose of this table is mainly to help the reader understand the raw data that drive the later regression-based analysis. It also, though, shows us some noteworthy patterns.

Table 2 Type of dispute by channel pursued

Note: The “trajectory” and “breakdown” rows do not all sum exactly to 100% due to rounding.

Concerning the types of disputes (the rows of the table): while fewer disputes overall were reported in 2010 than in 2002, the proportions constituted by the several dispute types were broadly similar across the two years. Thus, quarrels with neighbours were rampant in both studies, while land for home-building, water use, and consumer or labour disputes involving businesses were also cause for considerable amounts of strife. Divorce cropped up relatively infrequently in both surveys as a category of dispute, while squabbles with other members of one’s own family were highly common in the 2002 data, yet somewhat less so in 2010.

As shown clearly by the three columns under “Trajectory,” most disputes in these villages (as elsewhere) do not result in intervention by any third party whatsoever. Rather, in the most common trajectory, the aggrieved party confronts the source of the trouble directly. We call this “direct response” and it happened in nearly half of all disputes in both years. It is also very common simply to “lump it” (chi dian kui, ren le suan le, 吃点亏,忍了算了)—that is, do nothing about the problem and endure whatever harm or expense it caused. But, in a minority of conflicts, at least one third party was sought for help. The overall frequency of these responses changed little in the eight years between the two surveys, though villagers seem to have become somewhat more likely to seek third-party assistance (this happened in 19% of all disputes in 2002, 22% in 2010) and less likely to “lump it.” The difference is modest, but perhaps suggests a growing assertiveness and willingness to mobilize networks and resources.

The five columns on the right in Table 2 unpack the “third party” category, breaking it down into five subcategories of people or institutions who were enlisted for assistance in a dispute. Informal third parties include friends, relatives, and others who were not described as having an official position.Footnote 33 Village cadres included members of the VC or the village party committee. Township officials were the most common third party in the “higher government office” category; occasionally, county-level agencies were sought and, in a handful of instances, city or provincial offices.Footnote 34

As the data show, certain categories of disputes are far more likely than others to be brought specifically to village authorities for mediation. (The dispute types are sorted by reference to the 2002 data, with those for which village assistance was most common listed highest.) Thus, when disputes with neighbours are brought to any third party, it is very likely to be a village cadre—and this was true in both surveys. The same is largely true of disputes over water use and land for building villagers’ homes. Certain other types of disputes are more likely to be taken to more formal and higher-ranking institutions; liability disputes, for instance, often went to the township, to police, or to a court. The table thus illustrates the importance of looking at conflict in a way that differentiates among different types of disputes.

Overall, village authorities remained the most sought-after type of third party in rural disputes by a large margin, as indicated in the totals on the bottom two rows. About 40% (38% in 2002, 45% in 2010) of all conflicts involving third parties came to their door at one point or another.

3.3 Probability of Seeking Mediation

We used regression models in order to further understand the likelihood that various kinds of disputes, in varying contexts, will be taken to village mediation. The outcome variable in these models took one of five values, each corresponding to one general course of action that a party to a dispute could take: lumping it, responding directly to the other party, contacting an informal third party, seeking village authorities, and “spilling over”; spillover is our term for seeking help from formal entities beyond the village (township or higher levels of government, police, courts, and lawyers). Multinomial logistic regression was used to estimate the relative likelihood of disputes following one or another trajectory, for each of the eight dispute types. Table 3 shows this model.

Table 3 Multinomial logistic regression results on channels through which help was sought

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Note: “Lumped it” is omitted as the reference category of the outcome variable, and “Within own family” is omitted from the dispute-type dummy variables.

These raw results are not easy to interpret in plain language, so we used the model to generate predicted probabilities for the several outcomes.Footnote 35 Disputes in the eight categories received probabilities (from 0 to 1) for following each of the five paths. Table 4 displays the probabilities given by the 2002 and 2010 models, respectively, with all covariates set at their means—that is, for households with average ages, education levels, and incomes. The table shows how village-level mediation varies in comparison to other means of resolving a dispute and how its probability changed over time. We see here, again, the importance of differentiating by dispute type. The predicted probability of seeking village mediation ranges from around 1 to 26%, depending on the issue. This is consistent with decades of law and society research from a variety of countries, including China, finding that the nature of the grievance is the single largest predictor of what someone will do about it.Footnote 36

Table 4 Predicted probability of responses to disputes, by category

Note: Rows do not all sum exactly to 1.0 due to rounding.

Disputes over land for homes and disputes with neighbours both had a relatively high probability of village mediation in both years. Indeed, conflicts involving land for homes had as high as a one-in-four chance of leading to mediation in 2010. Divorce was on a par with these categories in 2002 but, by 2010, villagers had become somewhat less likely to take divorce-related issues to village cadres.Footnote 37 Instead, “direct response” dramatically grew in probability. In other words, divorces were more and more handled by the couples themselves; if they sought help, it was more likely to be from a lawyer or a court, and less from an acquaintance or a village cadre. Liability and water-use disputes had a middling probability of going to village mediation in both years (though, in each case, this probability was higher in 2010 than in 2002). Two other dispute types, debt and business, had a low chance of mediation in both years.

All told, what kinds of patterns do we see here over time? Generally speaking, village mediation remained a fairly popular form of recourse in 2010 as it was in 2002—for certain kinds of disputes, specifically those where the authority of community leaders pertains directly to the subject in question and where the stakes are not so high as to necessitate invoking the power of higher-ranking institutions. Only divorce cases became noticeably less likely to be taken to village cadres in 2010 than they were eight years prior, while several dispute categories became more likely to come their way. People dealing with disputes within the family became, over the eight years, much more likely to go to village authorities; the same was true of disputes over land for homes.

Do we see here a trend, as Lubman anticipated, toward more mobilization of formal institutions outside the village? Of all disputes taken to third parties, 38% were taken beyond the village in 2010, up from 33% in 2002. Such “spillover” became more probable over time specifically in cases of liability, water use, and debt. Thus, there was some movement toward more formal channels of resolution for high-stakes disputes, yet this was balanced by areas where formal institutions became less likely, such as land for homes (perhaps townships were trying to wash their hands of these kinds of troubles). Another reason that change over time did not entail less village mediation was a tendency to take to the village some issues that had previously been “lumped,” handled by the disputing parties themselves, or pursued through informal contacts. Informal third parties became less sought-after in four of the eight categories as of 2010 compared with 2002.

3.4 Variation by Household and Village

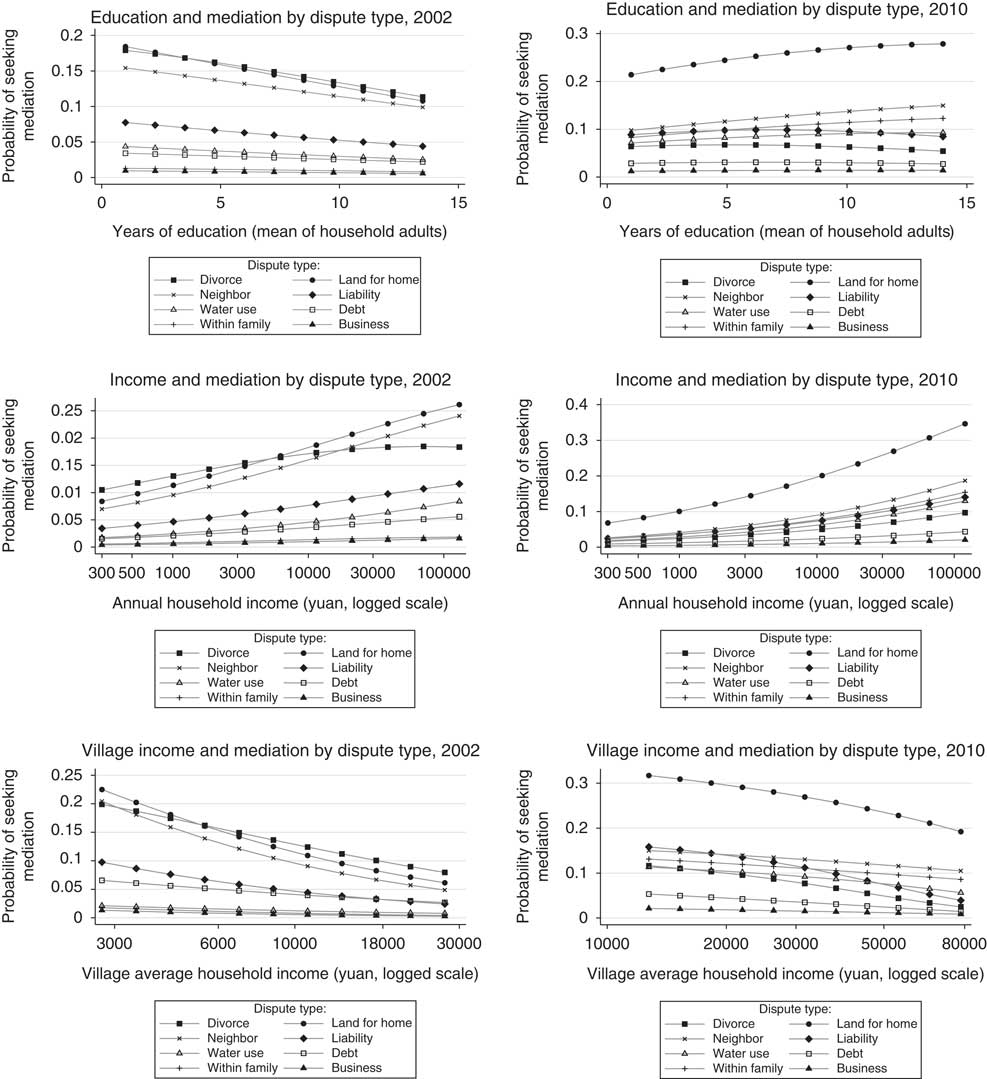

The regression models also show how the chances of seeking village mediation vary for different kinds of households—and in different kinds of villages. The graphs comprising Figure 1 are arranged in two columns, with the three graphs on the left depicting patterns derived from the 2002 data and those on the right from the 2010 data. From top to bottom, they show the predicted probability of mediation (y-axis) for households of varying educational levels (x-axis, top two graphs),Footnote 38 households of varying income levels (x-axis, middle two graphs), and for villages of different average income levels (x-axis, bottom two graphs).

Figure 1 Predicted probability of seeking mediation, by several variables

The 2002 data in the upper-left graph showed a clear pattern: households with lower levels of education were more likely than other families to seek out village mediation. We interpreted this as a possible result of differences in status; perhaps “better schooled families avoid[ed] the perceived indignity of having village leaders sort through their personal disputes.”Footnote 39 Whatever the reason for this relationship, it disappeared in the 2010 data. Households of different educational levels were equally likely to seek village mediation and, for two or three dispute types, families with more education were slightly more likely to seek mediation—the opposite of the 2002 pattern. If this institution was once sought out especially by those with lower educational status, that no longer appears to be the case.

But other relationships found in the 2002 survey did reappear in the new data. In analyzing the earlier survey, we noted that higher-income households had a greater chance of seeking mediation, all other things being equal. A reasonable explanation, we wrote, was that “those who are relatively wealthy or familiar with the local authorities feel more confident that they will receive a sympathetic hearing.”Footnote 40 The exact mechanism could vary; wealthier households may have a higher subjective sense of efficacy, for example, or village leaders themselves might have been more likely in 2010 to be drawn from wealthy families. Regardless, this pattern stayed robust over time.

All the above pertains to how individual households vary in their propensity to seek help from local authorities. Yet there is also variation not just within the village, but between villages. People living in higher-income communities had a smaller chance of pursuing village-level remedies compared to their counterparts in richer areas—a pattern evident in both 2002 and 2010. The likely explanation for this is that wealthier villages have easier access to formal institutions, and to formal institutions of higher quality. Indeed, the same model predicts that people living in richer villages are more likely than others to pursue “spillover” solutions.Footnote 41 The relationships between income and mediation are important keys to the social geography, if you will, of this institution; not all of the people are equally likely to access people’s mediation.

3.5 Disputants’ Assessment of Mediation

How effective is mediation? Qualitative research by the authors indicates that this is no simple thing to determine. As noted previously, state statistics on mediation seem to wildly overstate its effectiveness. Even apparently successful mediation (sometimes embodied in a formal agreement) can fall apart, and those who provide mediation often exaggerate the efficacy of their intervention. There is thus a real need to evaluate mediation from the perspective of the disputing parties themselves.

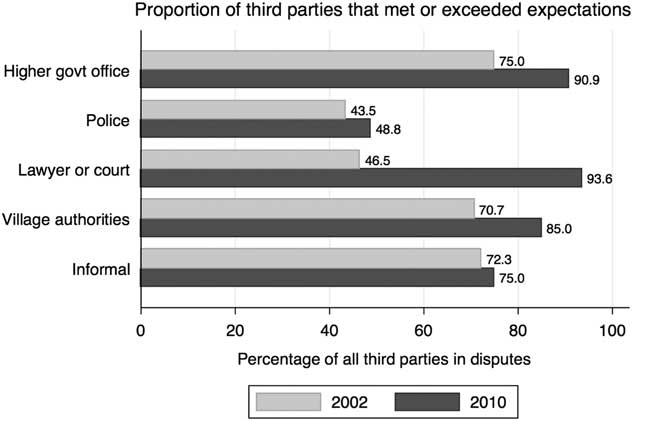

Our surveys contained measures of the disputants’ own assessments of their encounters with the third parties that they sought out. For each dispute in which a respondent (or his or her family member) solicited the assistance of one or more persons or agencies, the respondent was asked how well those entities performed. Performance was evaluated through this question: did the process through which the person or agency resolved the problem live up to your expectations?

Figure 2 shows how respondents evaluated five types of third parties whose help they sought in disputes. The figures show the percentage of disputes for which the process of intervention “met” or “exceeded” the respondent’s expectations. Around 71% of village authorities met or exceeded expectations in the 2002 survey, while 85% did so in the 2010 survey. In both years, higher government offices (again, these are primarily at the township level but occasionally at the county level or higher) tended to receive slightly more favourable scores than did villages. Police, by contrast, disappointed disputants more often than not in 2002 and again in 2010. They easily performed the poorest of all third parties. Meanwhile, lawyers and courts showed the most dramatic change over eight years, jumping more than 45% so as to meet or exceed the expectations of 94% of respondents who came to them.

Figure 2 Evaluation of village mediators vs. other third parties

Thus, village authorities garnered quite favourable ratings from disputants in 2002, but were rated even more highly in 2010. They are thus well regarded as a source of assistance in disputes. But they are not the only such resource that is seen favourably. Government institutions “above” the village also won approval, and more formal institutions like lawyers and courts grew strikingly in appeal, perhaps unsurprisingly given the pressure from above to build social harmony and preserve social stability. Information about petitions and appeals to higher levels has been used in local cadre performance-evaluation systems, incentivizing local officials to successfully resolve local problems.Footnote 42

4. CONCLUSION: CONTINUITY AND CHANGE, 2002–10

This paper has drawn upon the unusual resource of a repeated, fine-grained survey of actual disputes in rural China in order to understand how “people’s mediation” evolved or stayed the same from 2002 to 2010. There was great change in the Chinese countryside in the period falling between the two surveys, including the introduction of policies intended to improve the lives of rural folk, as well as rising incomes and intensifying struggles over village land. How did village mediation evolve in the eight years between the surveys? In what ways should we update our understanding of this institution? And what can we say about its role in the contemporary landscape of power and contestation in the Chinese countryside?

Our findings can be summarized as follows. Less disputing was reported in 2010 compared to 2002, and overall a smaller proportion of respondents to the later survey said that they had sought village mediation. Yet, for those who did find themselves in disputes, village authorities remained an important potential resource. Indeed, given a dispute, it even became more common for rural folk to seek them out for help in the later survey relative to the earlier survey.

In keeping with the “resilient village justice” hypothesis, then, mediation continues to be relevant, and fairly popular. It is far from ubiquitous; it likely has never been the all-encompassing phenomenon that some have imagined it to be. But it remains an important and frequently exercised option for people who are embroiled in disputes of certain kinds. Particularly for rural residents who find themselves in conflicts over land for homes or over the use of water, or in interpersonal disagreements with neighbours or family members, it is natural to approach village power-holders for help.

Clearly, then, the authority of village leaders remains important for people in these situations. In such disputes, the VC or party officials have sufficient standing to at least encourage the parties to come to some agreement. Whether this relies on officials’ actual control over the disposition of resources—such as over land for housing—or their perceived stature, the moral or customary authority that they wield, they are worth soliciting help from in a range of circumstances.

But the new survey also uncovered intriguing signs of evolution in terms of what kinds of civil disputes are taken to what kinds of fora. Villagers were markedly less likely, in 2010, to turn to third parties like relatives and elders who have no formal power to intervene. This would accord with the modernization hypothesis, which also receives a degree of support from the somewhat increased tendency to take certain problems outside the village—to government offices, police, lawyers, or courts. An increased probability of seeking such formal, higher-level institutions was seen in liability, water-use, and debt cases; here, the stakes are presumably high enough that the relatively casual arbitration or smoothing-over that village leaders could offer is just not enough. A greater likelihood of seeking formal sources of help was particularly prevalent in more affluent villages, which seem to have better access to such institutions. Yet, overall, villagers were only marginally more likely to pursue such channels in 2010—whereas only in divorce cases did they become less likely to approach village leaders for help. Our work makes it very clear that people in rural China handle different kinds of disputes in different ways, and that mediation plays a far greater role in certain kinds of close-to-home issues than in other forms of conflict.

People’s mediation can only stay relevant if the people find it useful, and apparently they do. According to the new survey, village authorities continued to be rated favourably with respect to their efforts to mediate disputes; indeed, disputants’ evaluations of them improved substantially from an already fairly high base. But, as of 2010, it was no longer the case that the help of village leaders was assessed more favourably than that of lawyers and courts, because the latter improved so strikingly compared to 2002. Assessments of the assistance provided by government offices in townships and counties also improved markedly. At least in these localities, then, some of the more formal agencies of the state and of justice became more hospitable to villagers in this eight-year span—even as police departments did not. Thus, village mediation remains a well-regarded resource for conflict resolution, yet it is only one among several such resources, some of which also appeared to rise in citizens’ estimation.

The 2002 data showed that village mediation was disproportionately pursued by less-educated citizens. (A similar pattern obtained for neighbourhood mediation in our Beijing survey of 2001.) This seemed to indicate that mediation served a special role as a resource for those who lack a sophisticated understanding of legal options or more formal remedies. No such relationship appeared in 2010, but the previously observed positive correlation between household income and village mediation did persist. If well-off families are most likely to summon the intervention of village authorities, this raises the question of how impartial the intervention might be. Quite possibly, the village head or party secretary could dispense justice in ways that favoured relatively rich and powerful households. It also suggests that people’s mediation is not equally easy for all of the people to draw upon, and that learning more about villagers’ differential access to this institution will be important for understanding how this institution functions in practice. All this highlights a point that we noted earlier: mediation has to be understood in the context of local power relationships.

Governance structures in the Chinese countryside concentrate substantial authority in the village—an ultra-local unit lying beneath what are considered the formal structures of the state. Essential decisions on issues such as the use of land, the management of other collectively controlled assets, and public infrastructure such as roads and schools all are made at the village level. This study illuminates another way in which villages figure in the lives of residents. It remains unquestionably true that village mediation constitutes a ready form of alternative dispute resolution in which conflict is addressed in a more local and personal fashion compared to settings like townships and courtrooms, even if the salience of these more formal institutions is slowly rising. Though mediation is far less ubiquitous or culturally mandated than some have suggested, it certainly continues to deserve study. Research must pay close attention to differences between households, between localities, and even among different types of disputes in order to contribute to a realistic and nuanced understanding of this enduring institution.