Ghana was the first Sub-Saharan country to gain independence, some 60 years ago; virtually all Sub-Saharan countries subsequently followed. Yet, in many countries, colonial authoritarianism was replaced by military regimes, autocratic rulers, and one-party rule. It was not until the 1990s that “the Third Wave” of democratization (Huntington 1991) swept across Africa.

The consolidation of democracy in Sub-Saharan Africa has been uneven. During the past 20 years, the “freedom status”Footnote 1 of 29 countries remained largely unchanged, with 10 countries classified as “not free,” 12 countries as “partially free,” and seven countries as “free” (Freedom House 2018).

Like democratization, legislative development in Africa has been uneven. Barkan (Reference Barkan and Barkan2009) pointed out that whereas African legislatures remain weak relative to the executive, most are more powerful and autonomous now than at any time since independence—and a small number have become institutions of countervailing power vis-à-vis the executive.

It is not surprising, then, that countries considered as “Liberal Democracies” or “Aspiring Democracies” by Freedom House (2018) also have the strongest legislatures according to Fish and Kroenig (Reference Fish and Kroenig2009). Furthermore, Pelizzo and Baris (Reference Pelizzo and Baris2015) found that political stability, lower corruption, stronger enforcement of the rule of law, and policy continuity were associated with better oversight and more accountable governments.

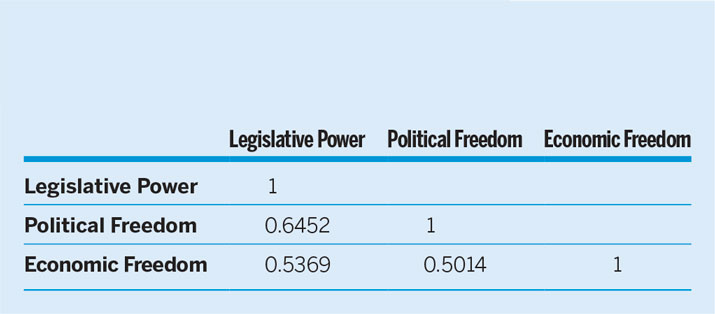

But is there association among stronger democracy, stronger legislatures, and better economic policies? We examine the various relationships among legislative power, democracy, and economic liberalization. Looking first at Fish and Kroenig’s (2009) index of legislative power and the most recent data on political freedom (Freedom House 2018), we found a strong correlation of 0.6452, supporting Fish’s (2006) contention that stronger legislatures equal stronger democracy. There also is a moderate correlation between stronger democracies and more liberal economic policies and greater economic freedom (0.5014), as well as between legislative oversight and economic freedom (0.5369) (table 1).

In general, this statement holds: there is a strong association among democracies, legislatures, and economic freedom.

Table 1 Cross Correlations for 2018

There are significant outliers. Both Lindberg and Zhou (Reference Lindberg, Zhou and Barkan2009) and Stapenhurst and Pelizzo (Reference Stapenhurst and Pelizzo2012) highlighted Ghana’s democratization as one of the political success stories in Africa. At the same time, however, its legislative power is weak and possibly becoming weaker (Draman Reference Draman2018). Conversely, Rwanda has a low score regarding political freedom but a relatively high score in terms of legislative power—reflecting perhaps President Kagame’s tight control of power but encouragement of policy debate within parliament.

In short, as Africa has moved beyond colonial authoritarianism, some countries have seen further political liberalization whereas others remain stuck in single-party states or under another form of authoritarianism. In general, this statement holds: there is a strong association among democracies, legislatures, and economic freedom. However, given significant outliers, more research at both the regional and the country levels is required to better understand these relationships.