Introduction

Worry, the cardinal symptom of generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), is a response to perceived threat (Borkovec et al., Reference Borkovec, Alcaine, Behar, Heimberg, Turk and Mennin2004; Davey, Reference Davey, Davey and Tallis1994). When people worry, they are, by definition, paying attention to the perceived danger and its implications for the safety of themselves and/or others. A more detailed definition of the process of worry has been covered by Gústavsson et al. (Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021). The issue addressed here is what do people with GAD worry about, and more importantly, how can they be helped to worry less? The answer to the first question is just about anything personally important. However, this does not help us distinguish the worry in GAD from any other type of worry because people with GAD worry about the same subjectively important matters as people not diagnosed with GAD (Breitholtz et al., Reference Breitholtz, Westling and Öst1998; Breitholtz et al., Reference Breitholtz, Johansson and Öst1999; Craske et al., Reference Craske, Rapee, Jackel and Barlow1989; Dugas et al., Reference Dugas, Freeston, Ladouceur, Rhéaume, Provencher and Boisvert1998a). Although the focus of threat is not different, the impact is much worse. To understand GAD, we need to understand why those affected by it are more anxious than others, and why this is more persistent. People with GAD spend more time worrying than less anxious people and experience the worries to be more difficult to control. The persistence and adverse impact of worry therefore has something to do with the way in which people with GAD worry. Usually, worry is self-limiting so the worry bout will cease when the person feels that they have found a subjectively acceptable solution to thwart the problem or threat. However, when no acceptable solution is found, the worry will tend to persist (Davey et al., Reference Davey, Eldridge, Drost and MacDonald2007). When it comes to GAD, we must be able to explain why a person with GAD gets stuck in worrying about their kid’s birthday party, their sleep efficiency, the health of their loved ones, or their relationship with friends.

The ideas elaborated in this paper were developed within the scientist-practitioner framework (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis2002). As such, they were developed within clinical practice and grounded in evidence-based clinical interventions. Importantly, these ideas are the results of working with patients that had not benefited from previous treatment(s), collaboratively figuring out the patients’ experience of their problem and what needed to happen in therapy for them to achieve recovery. In this invited paper we have attempted to challenge current orthodoxy in theoretical explanations of GAD. In general, we believe that one of the problems of the GAD literature is that recent theoretical explanations, and treatments derived from them, have moved unnecessarily too far from the generic cognitive model of anxiety disorders put forward by Beck et al. (Reference Beck, Emery and Greenberg1985) which has inspired successful treatments for all other anxiety disorders (e.g. Clark, Reference Clark, Hawton, Salkovskis, Kirk and Clark1989). Our proposal is that we go back to the basic tenets of the cognitive theory of emotional disorders to sort out the theoretical heterogeneity that has been growing in the GAD literature ever since its inclusion in the DSM-III.

Theoretical models of GAD

Some previous models of and approaches to GAD have been translated into clinical practice. What follows is a brief discussion of four models which have greatly influenced treatment and research, and/or been found to have some value in treating GAD. This will be followed by an extensive discussion about the original cognitive model of GAD put forward by Beck et al. (Reference Beck, Emery and Greenberg1985) and the revised cognitive model of GAD (Gústavsson et al., Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021).

The avoidance model of worry

The avoidance model of worry (AMW; Borkovec et al., Reference Borkovec, Alcaine, Behar, Heimberg, Turk and Mennin2004) is based on the two-stage theory of fear (Mowrer, Reference Mowrer1947) and conceptualises worry as a cognitive avoidance strategy that is negatively reinforced via the inhibition of stressful imagery, somatic symptoms, and emotions. Furthermore, positive beliefs about worry, i.e. worry is an effective problem-solving strategy, are reinforced due to the non-occurrence of negative events, which is attributed to worrying. The clinical implications for the AMW are based on strategies that enhance habituation and more effective conditioned stimulus exposure, such as graded stimulus control (worry time and worry-free zone), applied relaxation, and exposure to feared events (Behar et al., Reference Behar, DiMarco, Hekler, Mohlman and Staples2009; Borkovec et al., Reference Borkovec, Alcaine, Behar, Heimberg, Turk and Mennin2004). The research group behind the AMW (Borkovec et al., Reference Borkovec, Alcaine, Behar, Heimberg, Turk and Mennin2004) has suggested possible etiological factors in the development of GAD, such as insecure attachment with caregivers (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1982) and their role in the maintenance of current problems, for example via maladaptive interpersonal behaviours (Borkovec et al., Reference Borkovec, Alcaine, Behar, Heimberg, Turk and Mennin2004). Recently, the AMW has been developed further by incorporating findings from information-processing research into the conceptualisation of pathological worry (Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Beale, Grey and Liness2019). Traditionally, the AMW has not been offered as stand-alone therapy but has incorporated elements from other models of GAD, such as traditional cognitive therapy techniques including cognitive restructuring (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Emery and Greenberg1985), interpersonal therapy (Borkovec et al., Reference Borkovec, Newman and Castonguay2003) and applied relaxation (AR; Öst, Reference Öst1987).

The meta-cognitive model

The meta-cognitive model (MCM) (Wells, Reference Wells1999; Wells, Reference Wells2008) draws on the self-regulatory executive function model (S-REF; Wells and Matthews, Reference Wells and Matthews1996) and proposes a pattern called the cognitive-attentional syndrome (CAS) causing psychological disorders (Wells, Reference Wells2008). The S-REF serves to achieve or maintain specific goals that are determined by metacognition (Wells and Matthews, Reference Wells and Matthews1996; Wells, Reference Wells2008). The CAS is thought to maintain exaggerated threat beliefs through focusing attention on internal events (such as worry or intrusive imagery) perceived as threatening, as opposed to information that could correct meta-cognitive beliefs, and unhelpful coping behaviours (Wells, Reference Wells2008). The MCM proposes that in GAD negative meta-cognitive beliefs about worry are the key maintenance factors. It highlights the role of both positive (linked to type 1 worry) and negative beliefs of worry (linked to type 2 worry). Positive beliefs about worry (‘Worry helps me cope’) increase motivation to use worry as a problem-solving strategy (Borkovec et al., Reference Borkovec, Alcaine, Behar, Heimberg, Turk and Mennin2004), but negative beliefs about worry (‘Worry can make me lose control’) gives rise to meta-worry (worry about worry) where the ongoing presence of worry and associated emotional symptoms are (mis)interpreted as potentially harmful (Wells, Reference Wells1999). Meta-worry then leads to counterproductive thought control strategies and behaviours (e.g. reassurance seeking and avoidance), active threat monitoring and rumination (Wells, Reference Wells2008). These counterproductive strategies serve to maintain the negative meta-cognitive beliefs by focusing attention to the presence of worry and unpleasant bodily states, which in turn increase the intrusive nature of the worry and perceived danger preventing access to information that could disconfirm the meta-cognitive beliefs.

The intolerance of uncertainty model

According to the intolerance of uncertainty model (IUM), intolerance of uncertainty makes patients with GAD appraise felt uncertainty as potentially dangerous (Dugas et al., Reference Dugas, Freeston, Ladouceur, Rhéaume, Provencher and Boisvert1998a; Dugas and Robichaud, Reference Dugas and Robichaud2007). Felt uncertainty in turn triggers positive beliefs about worry, negative problem orientation and cognitive avoidance. In its original form the IUS model indicated that beliefs about uncertainty, worry and problem orientation should be targeted in treatment using self-monitoring techniques, cognitive restructuring, and exposure. However, an updated version of the IUS model explicitly targets beliefs about uncertainty via behavioural experiments, without targeting positive beliefs about worry or other factors in the original IUM (Dugas et al., Reference Dugas, Sexton, Hebert, Bouchard, Gouin and Shafran2022; Hebert and Dugas, Reference Hebert and Dugas2019). Although the IUM informs an effective treatment for GAD (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Koole, Huibers, Berking and Andersson2014) some theoretical issues remain. In its original form specificity of intolerance of uncertainty was claimed (e.g., Ladouceur et al., Reference Ladouceur, Dugas, Freeston, Rhéaume, Blais, Boisvert, Gagnon and Thibodeau1999). However, later research has indicated that beliefs about uncertainty are not specific to GAD (Carleton et al., Reference Carleton, Mulvogue, Thibodeau, McCabe, Antony and Asmundson2012; Holaway et al., Reference Holaway, Heimberg and Coles2006; Romero-Sanchiz et al., Reference Romero-Sanchiz, Nogueira-Arjona, Godoy-ávila, Gavino-Lázaro and Freeston2015). Furthermore, Gústavsson et al. (Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021) argued that while uncertainty is an important concept to conceptualise GAD, we can expect beliefs about uncertainty to interact with other important core beliefs (Beck, Reference Beck1976). A shared limitation of the models discussed so far is that none of them can successfully ‘explain when worry is an adaptive coping strategy and when it is problematic’ (Gústavsson et al., Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021).

Applied relaxation

AR (Öst, Reference Öst1987) is a pragmatic treatment approach built on the premise that those with GAD are hyper-aroused. Therapy aims to teach the patient a coping technique based on the broad principles of behavioural therapy. AR is not a specific treatment model for any disorder but has been applied to the treatment of several anxiety disorders (for review, see Öst and Breitholtz, Reference Öst and Breitholtz2000). AR is efficacious for treating GAD both as a stand-alone treatment and when delivered in a multi-modal treatment package including exposure techniques or cognitive restructuring (Borkovec and Costello, Reference Borkovec and Costello1993). The rationale for AR is that the patient needs to learn to recognise early signals of anxiety and develop new ways to cope with symptoms of anxiety (Öst, Reference Öst1987). The patient is gradually taught progressive relaxation techniques, first in therapy settings and later applied to real life using exposure strategies where the patient is exposed briefly to anxiety provoking situations, and he applies the relaxation skills he has learned. Importantly, Öst (Reference Öst1987) states that the goal of the exposure is not habituation of the anxiety response, but to create opportunities for the patient to learn that he can cope with anxiety.

The cognitive model of GAD

In the seminal work Anxiety Disorders and Phobias: A Cognitive Perspective, Beck et al. (Reference Beck, Emery and Greenberg1985) provided the first attempt to conceptualise the experience of people diagnosed with GAD from a cognitive perspective. He proposed that fear of failure and its consequences characterised the theme of threat in GAD and that a patient’s belief systems incorporated unhelpful belief systems about themselves (I’m a failure), other people (Others can’t be trusted), and the world (The world is unfair), i.e. the cognitive triad. David M. Clark (Reference Clark1986) extended the model to cover threats more generally. He also further elaborated this cognitive understanding of GAD when he outlined the main issues in GAD as beliefs and assumptions about ‘acceptance, competence, responsibility, control, and the symptoms of anxiety themselves’ (Clark, Reference Clark, Hawton, Salkovskis, Kirk and Clark1989). In this cognitive account the focus was on the maintenance of exaggerated threat perception, where the idiosyncratic meaning of the threat was the most important aspect of the formulation. Even though early evidence indicated that this conceptualisation of GAD informed a highly effective treatment for GAD (Arntz, Reference Arntz2003; Butler et al., Reference Butler, Fennell, Robson and Gelder1991), other theories of GAD have gained more research evidence and theoretical attention; for example, the AMW (Borkovec et al., Reference Borkovec, Alcaine, Behar, Heimberg, Turk and Mennin2004), the MCM (Wells, Reference Wells1999) and the IUS (Dugas et al., Reference Dugas, Gagnon, Ladouceur and Freeston1998b). However, these models have not been shown to produce more efficacious treatments for GAD, the IUM (g = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.24–1.48) and the MCM (g = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.26–1.31), than the original cognitive therapy for GAD (g = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.35–1.65) (for review, see Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Koole, Huibers, Berking and Andersson2014).

Here it is proposed that it was not necessary to abandon the original work done by Beck but rather to update it based on D.M. Clark’s 1989 article and subsequent work in that framework. Furthermore, we propose that the Beckian cognitive understanding of GAD should be used as a core model to improve our treatments for GAD, with relevant incorporations from other theoretical models of GAD and other anxiety disorders. For example, the mood-as-input hypothesis (e.g. Davey and Meeten, Reference Davey and Meeten2016; Startup and Davey, Reference Startup and Davey2001) provides an insightful way to understand the preservation of worry but has never translated into clinical practice. We believe that the mood-as-input hypotheses can be readily incorporated in the cognitive conceptualisation of GAD. The mood-as-input hypothesis claims that a synergistic interaction between ‘as many as can’ stop-rules (I must think this through) and negative emotional states maintain the preservation of worry (e.g. Davey and Meeten, Reference Davey and Meeten2016; Startup and Davey, Reference Startup and Davey2001). When the worrier starts the worry bout in a state of anxiety with the need to do everything they possibly can to arrive at the perfect solution, the ongoing state of anxiety will be taken as indicative of that the right solution has not been found. But why would a person with GAD use the ‘as many as can’ stop rule when worrying and not a non-GAD person? If we look at worry stop rules from the viewpoint of the original Beckian cognitive understanding of GAD, worriers use ‘as many as can’ rules to try and prevent serious failure, which would threaten to confirm underlying core beliefs.

The clinical implications of the core cognitive theory of anxiety in relation to GAD were not developed further and no systematic attempts have been made to refine its components. For example, Clark (Reference Clark, Hawton, Salkovskis, Kirk and Clark1989) described the importance of beliefs and assumptions about responsibility in the cognitive model of GAD published in Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Psychiatric Problems: A Practical Guide. This inclusion of inflated responsibility in the formulation of GAD was not explored further even though in recent years its potential importance has been ‘re-discovered’ (e.g. Gústavsson et al., Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021; Sugiura and Fisak, Reference Sugiura and Fisak2019; Startup and Davey, Reference Startup and Davey2003). This can be seen as part of a bigger problem when it comes to GAD. That is, since about 1995, the research focus in GAD has been on ‘worry processes’ but not on the idiosyncratic experiences of patients with GAD, where the cognitive understanding of emotional disorders is used to make sense of these experiences. This has led researchers to neglect the role of known key psychological maintenance factors of anxiety in GAD, namely, threat beliefs and safety-seeking behaviours. However, the inclusion of threat beliefs and safety-seeking behaviours in the conceptualisation of other anxiety disorders, such as social phobia and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), has driven greater understanding and further informed treatment developments in these disorders.

A revised cognitive model of GAD

Gústavsson et al. (Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021) offered a revised and updated cognitive account of GAD and worry building on the original Beckian cognitive model of GAD as core model. The following discussion further elaborates both the theoretical and clinical implications put forward by Gústavsson et al. (Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021). In that analysis it was argued that when worry is a response to a perceived threat based on over-estimation of awfulness and likelihood, the goal of the worrier will be to achieve complete certainty that the threat has been dealt with. Furthermore, it was proposed that people diagnosed with GAD have the tendency to experience problems as a threat due to over-estimation of their responsibility over the outcome and unrealistically high standards. We also expect to see in GAD specific beliefs about responsibility concerning exaggerated responsibility to eliminate dangers (‘It is my responsibility to keep everyone happy and safe’) and unrealistic standards of safety (‘If I am not certain that I am safe I am in danger’) (Mark Freeston, personal communication, 28 April 2022). Here it is important to note that the concerns, which are perceived as threats to the person with GAD, are: (1) to some extent realistic, (2) controllable to a certain degree, and (3) potentially soluble. However, they are experienced as (1) likely to go wrong (over-estimation of likelihood), (2) potentially harmful (over-estimation of awfulness), (3) difficult to solve (under-estimation of coping factors) and (4) unlikely to be mitigated by external or situational factors (under-estimation of rescue factors). The tendency to perceive problems or tasks as a serious threat is amplified by an inflated sense of responsibility for the outcome of personally important matters (work, finances, health of family, relationships, etc.) and perfectionistic standards (‘only 100% cuts it – no excuses’). Therefore, when feeling threatened, the person with GAD applies unhelpful ‘mood as input’ rules with the goal of doing everything in their power (‘as many as can’) to prevent the perceived threat from happening. Stopping short of certainty in terms of outcomes for which they perceive themselves as responsible (regardless of actual outcome), will confirm core beliefs (‘I was reckless’; ‘I’m a failure’; ‘I’m worthless’). Thus, the experience of heightened threat can lead to the resolve to be more careful ‘next time’. When no harm has occurred, this can be perceived as a near miss, suggesting that risk should be more carefully managed next time. In this way, the worrier gets stuck in counter-productive attempts to be completely sure that the (mis)interpreted threat has been fully dealt with, rather than arriving at a realistic appraisal of the extent of the actual problem and pursuing but failing to achieve the desired sense of complete safety. For example, a problem with a realistic solution such as an excessive credit card bill in January, is not dealt with by looking what solutions the bank offers and choosing one, but with trying to make sure that the family won’t starve this month due to your recklessness by (1) hypervigilance to how money is spent, (2) excessively checking the bank statement every day and (3) excessively asking your spouse whether your calculations are ‘correct’, with the goal to make sure that this situation never happens again.

Threat beliefs in GAD

As discussed previously we can map negative beliefs in GAD onto the cognitive triad. For GAD, as in other anxiety disorders, it is important to conceptualise all factors that affect threat appraisal: perceived awfulness × perceived likelihood/perceived ability to cope + rescue factors. Note also that these appraisals are dynamic, and may vary with anxiety itself. Salkovskis (Reference Salkovskis and Salkovskis1996) made the important point we can expect that these factors, and their synergistic interaction, may be different between the anxiety disorders. For example, in OCD, the threat can be perceived to be unlikely, but the perceived awfulness is so serious that the person finds it impossible to accept the tiniest uncertainty. In GAD, we often see that the problems are to some extent realistic, controllable to a certain degree and solvable. So, in GAD we would expect to see exaggerated awfulness, exaggerated likelihood, and under-estimation of coping abilities and rescue factors. Importantly, even though the perceived likelihood is exaggerated, the true likelihood is not necessarily that small. Meaning, what is feared could objectively happen if nothing is done, and probably something should be done. However, the over-estimation of the awfulness leads to over-estimation of likelihood. Furthermore, we suspect that it impairs perception of abilities to cope and the importance of rescue factors, which results in the use of unhelpful safety-seeking behaviours. This implies that as well as working to mitigate over-estimation of awfulness, therapy also needs to focus on enhancing the person’s belief in their ability to cope with or solve the problem which causes them concern.

Negative beliefs about self, others and the world

As mentioned earlier in this paper, negative beliefs in GAD can be expected to centre on ‘acceptance, competence, responsibility, control, and the symptoms of anxiety themselves’ (Clark, Reference Clark, Hawton, Salkovskis, Kirk and Clark1989). Examples of beliefs about self, others and the world, based on Beck et al. (Reference Beck, Emery and Greenberg1985), Clark (Reference Clark, Hawton, Salkovskis, Kirk and Clark1989) and our combined clinical experience, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Themes of negative core beliefs in GAD

Inflated responsibility for safety

Gústavsson et al. (Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021) sought to conceptualise the role of inflated responsibility in GAD. There it was proposed ‘that the theme of threat beliefs in GAD can be conceptualised as a tendency to understand the outcome of external everyday situations such as making the cake for your child’s birthday party, taking exams, or the well-being of your family and friends, in a way that you bear responsibility for the outcome and that you are accountable to others for the outcome’. A key feature of beliefs about responsibility in OCD is how they lead to appraisal of ego-dystonic (i.e. inconsistent to one’s belief system) thoughts, images, or impulse as indication for responsibility for harm (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1985). However, in GAD it is expected that beliefs about responsibility affect how ego-syntonic thoughts (i.e. consistent with one’s belief system) are appraised as an indication of responsibility for ensuring safety. Therefore, the thought is appraised as morally acceptable (and perhaps the non-occurrence of this thought would be appraised as immoral). Beliefs about responsibility for safety in GAD therefore drive the need to constantly be aware of what might go wrong and how to prevent it. We belief that (1) this definition of responsibility for safety, and (2) the conceptualisation of worry as a safety-seeking strategy (Gústavsson et al., Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021) can explain the relationship between pathological worry and positive-beliefs about worry (i.e. Dugas et al., Reference Dugas, Gagnon, Ladouceur and Freeston1998b). Failure to discharge the perceived responsibility entirely can result in confirming of negative core beliefs about self: ‘I’m a failure; I’ll never be able to cope’. Examples of core beliefs about responsibility are ‘It is my responsibility to make sure that everyone is happy and safe’ or ‘If something happens it would be my responsibility’. When under threat, there is an increased tendency to over-estimate responsibility for the outcome of external events which will lead to under-estimation of coping resources and over-estimation of the awfulness of a personally important situation. In GAD these tendencies will be exaggerated, and the person also believes (1) that they are a failure (self), (2) that they have not ensured that the world is safe, and (3) that other people are judgemental of such failures. As the threat appraisal in GAD is based on over-estimation of responsibility for ensuring safety, and importance of meeting exaggerated criteria of responsibility, the consequent safety-seeking behaviour will be aimed at further efforts to meet the exaggerated criteria. However, these unrealistic criteria cannot be achieved, resulting in a perceived failure in meeting the desired (but excessive) requirement for a sense of safety; despite actual safety in terms of outcome, the person perceives themselves as having failed in this respect. The exaggerated threat appraisal, unrealistic demands of responsibility and performance and the continued use of safety-seeking behaviours will therefor maintain and increase the gap between desired safety and felt sense of safety, maintaining the problematic core beliefs and tendency to experience anxiety (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Negative core beliefs, including beliefs about responsibility for safety, and key psychological maintenance factors based on the revised cognitive model of GAD.

Perceived uncontrollability of worries

Any theoretical model of GAD must be able to explain how the worry becomes uncontrollable and the associated distress. The meta-cognitive model incorporates negative meta-beliefs about worry such as ‘Worry can make me go mad’, in its formulation of excessive worry (Wells, Reference Wells1999). However, we propose that negative beliefs about ability to cope and their interaction with unrealistic standards for safety can further explain this phenomenon as well as negative meta-beliefs about worry. It is possible that negative beliefs about ability to cope are related to e.g. experiences of feeling unable to control difficult situations or negative feedback about abilities to cope with difficulties. For example, a newly graduated primary-school teacher is thinking about his new role which he is taking up next month. The first anxious thought is ‘What if I am not good at this and everyone notices?’. If this turned out to be true, he knows that this would confirm the core belief ‘I’m a total failure’. As a response he starts to go over in his mind everything he learned in his studies, checks the curriculum for every subject he will teach and revises repeatedly and looks for information online on how to manage when stressed. When the anxiety increases as he engages in more safety-seeking behaviours, which triggers more distress: ‘Why is it always like this? I can’t cope with anything! Eventually I will lose my mind and end up alone’. In response to these anxious thoughts, he tries to supress the worries and distract himself by mindlessly watching the television and going through social media at the same time, but that only seems to make the worries more intrusive and perceived as more uncontrollable, increasing the distress, and conforming the core belief ‘I am weak and not able to cope with anything’. In this case it will be important to help the newly graduated teacher to experience that his coping abilities are better than he believes by dropping safety-seeking behaviours and using other more helpful coping behaviours to deal with the anxiety as a behavioural experiment. This understanding of felt uncontrollability of worries also offers a cognitive explanation of why AR (Öst, Reference Öst1987) is successful in treating GAD. As discussed above, AR teaches patients to go into anxiety provoking situations (therefore dropping safety-seeking behaviours such as hypervigilance or thought suppression) and applying progressive relaxation on the premise that they can control their anxiety, offering an opportunity to test their exaggerated threat beliefs.

Safety-seeking behaviours in GAD

GAD is the only anxiety disorder conceptualised in the DSM that does not have an avoidance behaviour criterion (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This can probably be explained by considering how GAD was originally conceptualised as a residual disorder and therefore no attempt made to specify in what way it was similar or different to the other anxiety disorders. Furthermore, at the time GAD was included in the DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association, 1980), avoidance was thought only to be significant in phobic disorders, such as social phobia or specific phobia, but not GAD. Barlow et al. (Reference Barlow, Cohen, Waddell, Vermilyea, Klosko, Blanchard and Di Nardo1984) stated that ‘exposure is of little or no use to those with generalised anxiety disorder … since they avoid nothing to begin with’. However, as early as 1987, studies indicated that patients diagnosed with GAD did engage in avoidance behaviour (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Gelder, Hibbert, Cullington and Klimes1987). It may be that this view of avoidance being irrelevant to the maintenance of GAD impeded our efforts to understand further the role of safety-seeking behaviours in GAD.

Patients diagnosed with GAD have been reported to engage in similar safety-seeking behaviours to patients with other anxiety disorders. Both research and clinical experience indicates that patients diagnosed with GAD report procrastination, excessive reassurance seeking, excessive checking, excessive preparation, excessive information seeking avoidance and thought control strategies (Beesdo-Baum et al., Reference Beesdo-Baum, Jenjahn, Höfler, Lueken, Becker and Hoyer2012; Woody and Rachman, Reference Woody and Rachman1994). Safety-seeking behaviours have the intended function of preventing or minimising the threat perceived (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1991). Therefore, in GAD, where the theme of threat is about failure to fulfil perceived responsibility and being negatively evaluated by others, safety-seeking will be focused on trying to make sure that responsibility has been fulfilled and blame has been avoided. This meaningful link between the perceived threat and safety-seeking responses is a key part of the idiosyncratic case formulation for every patient and lays the groundwork for testing out what needs to happen in treatment for the patient to attain his goals.

Selective attention in GAD

It is well established that people who are anxious consistently deploy attention towards threat stimuli (MacLeod and Mathews, Reference MacLeod and Mathews1988). Specifically, patients diagnosed with GAD have been shown to exhibit attentional bias toward threatening stimuli (Goodwin et al., Reference Goodwin, Yiend and Hirsch2017). Furthermore, a recent paper reported results indicating that compared with non-clinical controls, participants with GAD exhibited a bias to avoid mild threat images (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Quigley, Carriere, Kalles, Smilek and Purdon2022). Information-processing biases may operate quite differently when a stimulus is symbolic as opposed to real threat (Thorpe and Salkovskis, Reference Thorpe and Salkovskis1998); this research indicated that, where an actual threat is present, people divide attention between threat and safety. These results imply that clinical interventions do not need to specifically address attentional biases in GAD but rather attentional control, i.e. what is being attended to (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Quigley, Carriere, Kalles, Smilek and Purdon2022). Research has indicated that attentional bias measured in GAD is non-specific, that is, it is across several domains, which should be expected given the range of worry topics experienced by GAD patients (Goodwin et al., Reference Goodwin, Yiend and Hirsch2017). Although it has been suggested that attentional bias toward specific, idiosyncratic threats is not present in GAD, research on the topic is non-existent. That is understandable, both because research on specific threat beliefs in GAD is limited (Gústavsson et al., Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021) and a measure of GAD-specific threat beliefs (such as the Agoraphobic Cognitions Questionnaire for panic disorder; Chambless et al., Reference Chambless, Caputo, Bright and Gallagher1984) has never been developed.

As has been proposed by Gústavsson et al. (Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021), and in this current paper, the cognitive model of GAD assumes that sets of idiosyncratic core beliefs are involved in GAD even though the worry topics are varied. Therefore, when formulating the role of selective attention with a GAD patient, it needs to be understood in relation to the specific threat beliefs to which they are sensitive (and therefore likely to attend to) and elevated evidence requirements for safety. It is expected that attention will not only be directed towards the perceived threat but also towards information regarding perceived ‘safety’. The model assumes that the GAD patient will pay attention to the feared situation or object and simultaneously to various internal information, such as emotion, physical sensations and ‘felt sense of safety’ to determine whether the threat has been fully and completely dealt with. However, because the desired level of safety is highly unrealistic or even impossible (‘I need to be 100% sure that I have done enough’) and unhelpful information is used to determine safety (attention to emotions and sensations), the desired goal is never reached. As a result of the perception of threat, the person with GAD may also operate elevated evidence requirements (e.g. Davey and Meeten, Reference Davey and Meeten2016). These unhelpful strategies are, however, reinforced by the fact that the feared harm does not occur, reinforcing the perceived value of the search for the highest possible level of perceived safety (Davey and Meeten, Reference Davey and Meeten2016; Gústavsson et al., Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021; Startup and Davey, Reference Startup and Davey2001).

Clinical implications of the revised cognitive model of GAD

The revised cognitive model of GAD incorporates all therapeutic techniques derived from the cognitive model of GAD, such as increasing awareness of thoughts, emotions and behaviours and challenging automatic thoughts (e.g. Beck et al., Reference Beck, Emery and Greenberg1985; Clark, Reference Clark, Hawton, Salkovskis, Kirk and Clark1989; Clark and Beck, Reference Clark and Beck2011). A key addition to the formulation here is the incorporation of the tendency to over-estimate responsibility for outcomes and accompanying safety-seeking behaviours. The role of inflated responsibility in threat perception and safety-seeking links all the different worry topics. So instead of challenging every single worry using thought records or behavioural experiments, the idiosyncratic meaning-making structure (including the perceived threat, core beliefs and assumptions) is conceptualised (theory A), and the patient and therapist will collaborate, using the cognitive model of anxiety disorders, to develop an alternative, less-threatening understanding of the problem (theory B) (Gústavsson et al., Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021; Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis and Salkovskis1996). The formulation has at its heart the idiosyncratic meaning which can be applied to every worry topic important to the patient. This deals with a problem that therapists often face when working with GAD, namely that the focus of worry often changes and dealing with topics one by one is of limited use (Wells and Butler, Reference Wells, Butler, Clark and Fairburn1997). Treatment which utilises an idiosyncratic formulation that targets the key psychological maintenance factors of the problem can make the aim of interventions more focused and meaningful. Another key advantage of developing theory A (‘I’m a failure’) and the alternative theory B (‘I’m someone who wants to be completely certain that I’m not a failure, and tries too hard as a result’) is that this conceptualisation offers an opportunity to normalise and account for the patient’s experience and a realistic hope for learning new ways to deal with the anxiety, which can foster the patient’s motivation for change. Here it might be ‘my past experiences have made me particularly sensitive to the idea of failure’. The aim of treatment is therefore to use a combination of therapeutic techniques, starting with formulation and shared understanding based on detailed discussion of the person’s experience, then helping them to interrogate that alternative, less threatening account by using strategies such as behavioural experiments, attentional training, and challenging appraisals to test theory A and B. The revised cognitive model puts more emphasis on behavioural experiments then the original model. Behavioural experiments should: (1) test the effects of safety-seeking behaviours on anxiety and worry, (2) aim to test threat beliefs by dropping safety-seeking behaviours, (3) test the effects of shifting attention ‘from worries to what is front of you’ to gather information on to what degree worries are uncontrollable, and (4) challenge negative core beliefs and assumptions, with focus on beliefs about responsibility. In essence, behavioural experiments give the person access to new experience in a way which integrates with the formulation. The key therapeutic modules based on the revised cognitive model of GAD are proposed to be as follows:

-

(1) Psychoeducation about worry and anxiety/socialisation to CBT;

-

(2) Formulation based on a shared understanding of the problem (theory A/B);

-

(3) Increasing awareness about anxiety and worry;

-

(4) Attention training to increase externally focused attention and engagement;

-

(5) Testing the felt uncontrollability of worries;

-

(6) Testing threat beliefs and core beliefs with behavioural experiments;

-

(7) Collecting information to affirm the shared understanding.

Case formulation

A 29-year-old male presenting with GAD sought treatment because he felt his anxiety was getting worse. He has received CBT for GAD previously but did not benefit from it and has now been on anti-depressants, anti-histamines and benzodiazepines for a couple of years and reports that the anti-depressants most often take the edge of the physical symptoms. He lives with his life partner at their own apartment and has recently graduated as a primary-school teacher and is supposed to start work as a teacher after the summer holidays. His main topics of worry were work, relationship, finance, family and friendships. The formulation of a recent worry bout is presented here (see Fig. 2). When developing a formulation of a recent worry episode it is important to start with a specific memory. That is, we want to ask the patient to think about a recent, typical, worry episode and try to identify the moment it started (‘What was the first sign of trouble?’). That gives reliable information about the worry trigger and the immediate threat perception which starts the episode.

Figure 2. Example of a GAD formulation focusing on key maintenance factors.

At this point in the formulation process we do not have information about the patient’s core beliefs; the focus is on maintenance factors. However, this initial formulation is already giving us information about what underpins his worries. In Fig. 2 we can see that the first ‘What if…?’ question that popped in his head was ‘What if I am not good at this and they (students and other teachers) will notice it?’. Here it is important to remember that what we are interested to understand is why this ‘What if…?’ question is so important for the patient. We want to understand what this would mean to him if true and what would be the consequences (perceived awfulness). In this instance the possibility of performing inadequately (by his own standards) and others noticing it in a critical way would mean that he is a ‘a total failure’.

One of the main complaints of this patient is that he feels unable to control the anxiety and worry and that causes him great distress. When drafting the formulation, it became clear that the fact that he was ‘once again’ anxious triggered a secondary appraisal: ‘Why is it always like this? Why can’t I manage my anxiety? I will lose my mind in the end; people will reject me and I’ll be alone forever’. His attempt to deal with the anxiety in this anxious state was to suppress the worries, avoid his spouse and try to control his breathing.

As therapy progressed and more examples of worry episodes were formulated, a theme began to emerge. Irrespective of the worry topic, the patient was often concerned with being a burden on others and people would see him as a failure. The formulation of the problem indicated that the most important core beliefs behind every worry topic (work, relationship, finance, family and friendships) were: ‘I am weak and can’t cope with difficulties; it is my responsibility to keep everyone happy and safe’. An extended formulation including beliefs about responsibility is presented in Fig. 3.

Figure 3. Example of a GAD formulation with focus on maintenance factors and negative core beliefs.

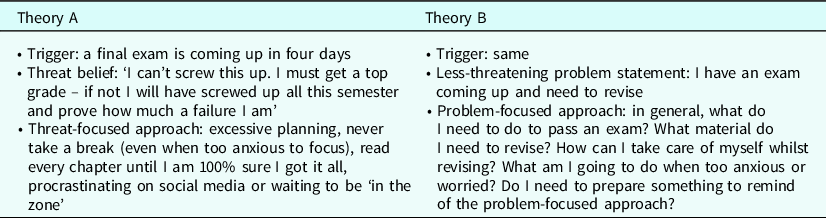

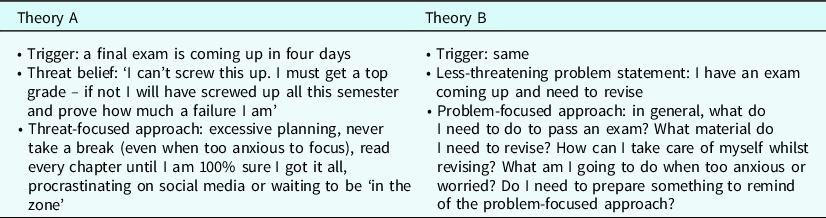

Using the formulation, we can begin to develop theory A and B. Theory A is the understanding of the problem that the patient brings with him when starting therapy (‘I am a failure; I need to worry to be able to cope’) but theory B is an alternative, less-threatening understanding of the problem (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis and Salkovskis1996). When developing a shared understanding of the problem, it can be helpful to discuss what past experiences lead to the formation of these unhelpful beliefs. Understanding of what experiences were important to form these beliefs can be used to discuss the accuracy of theory A and B. No-one is born with the belief ‘I’m a failure’. So, understanding where this idea comes from and understanding that ‘you have learned to think about you in this way’ can be a powerful way of beginning to explore alternative understanding (theory B) of the problem (see Table 2).

Table 2. Theory A and theory B in GAD based on a co-developed formulation

When the idiosyncratic formulation is being co-developed in sessions the patient should be encouraged to try to formulate recent worry episodes between sessions to increase awareness of what is happening when feeling anxious and worried. Furthermore, keeping a Worry History Outcome (e.g. Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Beale, Grey and Liness2019) can help increase awareness and it can also be a good start to gather information about the nature of the problem (theory A versus theory B).

As patients with GAD pay too much attention to possible and actual threats, it is important to demonstrate the role of attention in the maintenance of the problem. However, this can be difficult to achieve because the worries are perceived as uncontrollable, and the patient might be sceptical about his ability to control his attention. We propose that attention training could be incorporated in the treatment in GAD in a similar way it is included in the Clark and Wells (Reference Clark, Wells, Liebowitz, Hope, Schneier and Heimberg1995) cognitive therapy for social anxiety disorder. That is, attention training is utilised to help patients practise shifting their attention from their worries or perceived threat (internal) to something neutral in the environment (external). The goal of the attention is both to create a sense of control over attention as well as to assist with later behavioural experiments, where external attention will be used to gather information about what is happening instead of attention to perceived threat or internal information of safety. It is important that the attention training is introduced in an empathic manner. The patient should be reassured that this is a skill that needs to be practised consistently, and it will be difficult in the beginning.

This current model conceptualises the felt uncontrollability as a result of core beliefs about lack of coping abilities and distress from feeling overwhelmed by anxiety and worry for a prolonged time. Here it is important to test the effects of the existing coping mechanism, such as distraction or suppression of intrusive thoughts. This effect can be tested for example with the ‘white bear experiment’ (Wegner et al., Reference Wegner, Schneider, Carter and White1987) establishing that trying to suppress intrusive thoughts will make them more intrusive and distressing. As well as testing the negative effects of suppression strategies, the patient and the therapist need to figure out an alternative way to cope with the worries and the associated distress. Here is an opportunity to involve the principles of the attention training alongside doing a meaningful activity. A behavioural experiment could therefore look like this:

-

Situation: Next time I am alone at home and notice that a worry pops up;

-

Prediction: I will get frustrated and not able to calm myself down which will lead me to lose my temper with my spouse;

-

Experiment: (a) Do not try to suppress my worries; (b) actively try to shift my attention from the worries to what I am doing (remember to be compassionate to myself if this is difficult); (c) do a 20-minute exercise (or some other valued activity).

Subsequent behavioural experiments should focus on the effect of safety-seeking behaviours and testing threat beliefs and underlying core beliefs and assumptions. However, as discussed previously, sometimes the patient is worried about something that needs to be dealt with, but his threat perception is out of proportion. In that case it is important to help the patient figure out: (1) what needs to be done; (2) what is required of him in the situation; (3) how can he know that he has done his part. This basically means trying to conceptualise less-threatening understanding of the worry topic: shifting from threat perception to problem statement. This can be understood as theory A versus theory B but for a specific worry topic (see Table 3 for an example).

Table 3. Threat-focused (theory A) versus solution-focused (theory B) approach to a worry trigger

This revised CT conceptualisation of GAD implicates beliefs about responsibility as a key maintenance factor. As well as challenging core beliefs about self, others and the world, therapy should address unhelpful beliefs concerning responsibility for safety and the outcome of external situations with the aim of helping the patient to develop a more balanced, flexible beliefs and assumptions. These beliefs can be tested with de-catastrophising experiments, testing whether the use of safety-seeking behaviours, such as reassurance seeking, are helpful for dealing with the anxiety, and discussion and experiments around the patient’s objective versus perceived responsibility. Here it is important to note that we can expect that the patient really does bear some responsibility concerning the worry topic, such as maintaining good relationship with spouse, but the problem is that he over-estimates his responsibility for the outcome. Sometimes, people feel responsible for things which they cannot control, which can be helpful to identify. The responsibility pie chart can be helpful to map out to what extent responsibility is shared and figure out what could be a helpful and appropriate response to a personally important situation. Here we want to list all the parties that have something do with the outcome of a certain worry topic. The patient’s role in the outcome is added last to the pie chart after other parties have been included. For example, a young woman diagnosed with GAD is worried about the mental health of her friend who has made it known that her depression has recurred, and she is also worried about her boyfriend who has also been dealing with depression and substance abuse:

-

Situation: Friend and boyfriend having a difficult time with their depression being back;

-

Threat belief: ‘How can I be certain that I am fulfilling my responsibilities as a girlfriend and a friend?’; ‘They will think badly of me if I do not help them in every way I can’; ‘If I am not able to make them better, I am failing in being the perfect version of myself’;

-

Safety-seeking strategy: Think about a strategy to fulfil felt responsibility, devise a plan to divide the time between them equally, be attentive to their needs and give perfect advice.

As can be seen, the patient here feels responsible for the mental health of her loved ones (‘If I am not able to make them better, I am failing in being the perfect version of myself’). It is normal to be concerned about our loved ones and wanting to help. Importantly, we can and do assign ourselves some responsibility when it comes to our loved ones. We do have obligations to be there for them in time of need. However, as is evident in the above example, the patient is over-estimating her responsibility. She is putting the pressure on herself to ‘make them better’ and give perfect advice. Here, the responsibility pie chart could focus on the extent of people’s responsibility over their own mental health, the responsibility of loved ones, the mental health system and other factors that can negatively and positively impact mental health. This exercise is meant to help the patient see that she does have some responsibility, but that she tends to over-estimate the extent of her responsibility, resulting in unhelpful safety-seeking behaviours with the (unrealistic) goal of reaching felt sense of safety. When other factors have been accounted for, her role is discussed and what are realistic ways to fulfil the reasonable responsibility she does have towards her loved ones: ‘ask them what support they have and what they want and need from me’. This can help the patient to share responsibility with other people and practise ‘letting go’ and not trying to control the actions of others – i.e. acting as if it is not his/only his responsibility (theory B).

Summary and future directions

In this article we have offered an updated model of GAD based on the cognitive theory of anxiety disorders and presented its clinical implications and application. We argued that the original CT for GAD (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Emery and Greenberg1985; Clark, Reference Clark1986; Gústavsson et al., Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021) should be used as a core model and should be updated in line with new developments in cognitive theories of anxiety disorders. In this updated model, beliefs about responsibility for safety and for the outcome of personally important events and safety-seeking behaviours are given a central role to conceptualise the experience of people with GAD. Importantly, it gives the therapist and the client opportunity to understand what key psychological maintenance factors drive the tendency to worry and what needs to happen to reverse those factors. When working with GAD it is important to develop a case formulation in collaboration with the client, both to increase sense of control and motivation to change and as well as to guide treatment. Alternative, less-threatening explanation of the problem (theory B) is developed as opposed to the initial understanding of the problem that the patient brings to treatment (theory A). Behavioural experiments and attention training techniques are then utilised to test out these two competing theories of the problem with the focus on the disproportionate threat appraisal and other unhelpful beliefs about responsibility, coping abilities and standards of performance. Instead of challenging each worry topic individually, treatment is focused on changing the structure of the meaning making system (unhelpful core beliefs) and helping people to be more flexible in their responses to challenging situations. This updated cognitive account of GAD is firmly based in theory of psychopathology and empirically grounded clinical interventions. Furthermore, we believe that this current model of GAD offers theoretical and clinical parsimony by using the same psychological concepts to conceptualise GAD which are used in cognitive models of other anxiety disorders (e.g. Clark and Wells, Reference Clark, Wells, Liebowitz, Hope, Schneier and Heimberg1995; Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1985), resulting in easily transferable therapeutic skills and competence.

As discussed, it has been established that the original CT for GAD is an effective treatment; research on the proposed novel components is of course the next step. As inflated responsibility is hypothesised to play a pivotal role in the experience of people with GAD, we need to (1) establish that beliefs about responsibility in GAD differ to beliefs in OCD in terms of the focus of responsibility, i.e. external events (GAD) versus internal events (OCD), (2) develop a psychological measurement for responsibility beliefs in GAD to use in research and treatment, and (3) test whether change in responsibility beliefs drives reduction in worry, anxiety and impairment. Furthermore, we need to test how the hypothesised lack of belief in coping abilities in GAD affects the initiation and termination of safety-seeking (perception of safety and evidence requirement for safety). This work is currently under way by our research group.

Key practice points

-

(1) It is possible to formulate the experience of people diagnosed with GAD using known key psychological maintenance factors derived from the cognitive theory of anxiety disorders.

-

(2) Using the theory A versus B procedure grounded in formulation, the GAD patient can be helped to develop an alternative, less threatening (theory B) understanding of the problem as a shared understanding which can increase motivation for treatment engagement as well as help develop a treatment plan.

-

(3) Treatment of GAD should be driven primarily by formulation and incorporate psychoeducation, increased worry awareness, increasing external attention as opposed to internal attention and behavioural experiments to test perceived helpfulness of safety-seeking behaviours and exaggerated threat beliefs and gather evidence for ‘theory B’.

Data availability statement

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgements

Sævar Gústavsson would like to thank all his clients who have shared their experience of GAD with him, his mentors; Jón, Pétur and Paul, and Ó.G.J.

Author contributions

Sævar Gústavsson: Conceptualization (lead), Resources (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Paul Salkovskis: Conceptualization (supporting), Supervision (lead), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (lead); Jón Sigurðsson: Conceptualization (supporting), Supervision (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

Sævar Gústavsson is funded by the doctoral student research fund at Reykjavik University, grant no. 222019. Other contributirs received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

All authors have abided by the ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct set out by the BABCP and the BPS.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.