Introduction

Primary healthcare is considered as one of the most effective ways to promote the highest possible health standards for all by emphasising universal health coverage. The WHO defines primary healthcare as ‘a whole-of-society approach to health that aims equitably to maximize the level and distribution of health and well-being […] along the continuum from health promotion and disease prevention to treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care…’ (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2019).

Collaboration of primary care and essential public health functions is considered to be one of the building blocks of the primary health care approach together with people’s and communities’ empowerment and multisector action (WHO, 2018). Primary care services are clinical care services delivered on an individual basis that are accessible for everyone, dealing with the largest share of health complaints by a comprehensive approach in a continuous manner, and coordinated between levels of care (Starfield et al., Reference Starfield, Shi and Macinko2005). Public health for its part is often defined as ‘the art and science of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts of society’ (Winslow, Reference Winslow1920). Public health intervention is carried out at the population level. Notwithstanding the important differences between the two fields of practice, a collaboration between public health actors and primary care providers is often impeded by organisational or communication issues between professionals, such as problems in sharing data or developing a common vision for the community (Lebrun et al., Reference Lebrun, Shi, Chowdhury, Sripipatana, Zhu, Sharma, Hayashi, Daly, Tomoyasu, Nair and Ngo-Metzger2012; Pratt et al., Reference Pratt, Gyllstrom, Gearin, Lange, Hahn, Baldwin, VanRaemdonck, Nease and Zahner2018).

In recent years, some countries (Committee on Integrating Primary Care and Public Health; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Institute of Medicine, 2012; Booth et al., Reference Booth, Hill, Moore, Dalla, Moore and Messenger2016; Gosling et al., Reference Gosling, Davies and Hussey2016; Lionis et al., Reference Lionis, Petelos, Papadakis, Tsiligianni, Anastasaki, Angelaki, Bertsias, Mechili, Papadakaki, Sifaki-Pistolla and Symvoulakis2018) moved forward and created new local networks to integrate primary care and public health. However, accounts of these experiences are still sparse, evidence on health impacts is limited and there is a lack of literature on how to foster the development of these collaborations (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Barkley, De Maeseneer, van Weel, Kluge, de Wit and Greenhalgh2018). In countries with a strong primary care system, such as the Netherlands and England, linkages and articulation between primary care and public health are limited (Hone et al., Reference Hone, Macinko and Millett2018), and hamper the efficacy of primary healthcare.

The French primary care system is a ‘medium level strength’ system with a long history of professional non-hierarchic primary care model (Kringos et al., Reference Kringos, Boerma, Bourgueil, Cartier, Dedeu, Hasvold, Hutchinson, Lember, Oleszczyk and Pavlic2013). Since 2005, different reforms have been implemented to support the development of teamwork, skill mix and case management in primary care (Bourgueil et al., Reference Bourgueil, Clément, Couralet, Mousquès and Pierre2009, Reference Bourgueil, Fur, Mousquès and Yilmaz2008). Contiguously, public health policies have been decentralised with, in 2009, the creation of Regional Health Agencies (LOI n° 2009-879 du 21 juillet 2009 portant réforme de l’hôpital et relative aux patients, à la santé et aux territoires, 2009). Amongst other mandates, Regional Health Agencies are responsible for the implementation and adaptation of national health strategies through regional health programs. To this end, one of the instruments that are promoted is the local health contract. These contracts fostering local public health actions are co-signed by the Regional Health Agencies and local governments such as municipalities, syndicate of towns, or other subregional entities with contributions from other local partners such as local branches of state agencies. In local health contracts are defined priorities and a set of actions to be carried out for the next one–five years by aligning national health priorities with regional and local ones. It covers actions in health promotion, disease prevention and access to health services, with an overarching aim to reduce social and territorial health inequalities (LOI n° 2009-879 du 21 juillet 2009 portant réforme de l’hôpital et relative aux patients, à la santé et aux territoires, 2009).

Local health contracts intend to push local stakeholders from different sectors to join in their actions through local partnerships and engagement of the community in order to improve environmental and social contexts, to increase access to care, foster disease prevention and health-promoting actions (Haschar-Noé and Salaméro, Reference Haschar-Noé and Salaméro2016). These public health actions involve a diverse set of stakeholders (local elected officials, social services, health-related networks such as diabetes network, patient associations, hospitals, health professionals and also community-based associations and more).

Although no permanent funding is specifically devoted to local health contracts, Regional Health Agencies often fund the conduct of the diagnosis on which is based the identification of priorities and may share the cost of the coordination (full-time or part-time position) with the local authority. In addition, the signature of a contract comes with some benefits for the local partners. For instance, it creates an opportunity for local elected officials to claim legitimacy to intervene on health and display to their electorate their leadership on health and health-related (Salaméro and Haschar-Noé, Reference Salaméro and Haschar-Noé2017). For the above-mentioned local stakeholders relying on public subsidies to maintain their staff and activity, being involved in a local health contract may increase the likelihood of funding attribution through grant applications to the Regional Health Agencies (Haschar-Noé et al., Reference Haschar-Noé, Salamero and Honta2015; Honta et al., Reference Honta, Haschar-Noé and Salaméro2018). For other partners such as gyms, it is a way to promote their business plan such as by agreeing on providing special services to individuals oriented by primary care providers or by organising community activities to promote healthy lifestyles. Some authors suggest that the more concrete, aligned with regional priorities, and supported by local actors’ local plans are, the more likely they will attract funding from Regional Health Agencies (Haschar-Noé et al., Reference Haschar-Noé, Salamero and Honta2015; Salaméro and Haschar-Noé, Reference Salaméro and Haschar-Noé2017).

Local health contracts’ context may offer health care providers in primary care settings an opportunity to lead or get involved in public health actions. These actions could consist of an effective orientation to health promotion services for a better use of resources by individuals or for the involvement of primary care professionals in the community’s activities such as attending the sports festivals and discussing the physical activity. Therefore, theoretically, local health contracts may act as an instrument that potentially enhances primary healthcare and improves the health and well-being of individuals and the population. Today, as 10 years have passed since the introduction of the law defining the mission of primary care providers, creating Regional Health Agencies and introducing local health contracts, over 400 contracts were signed by local-level partners across the mainland and overseas French territories (Breton and Team CLoterreS, Reference Breton2020).

One important feature of local health contracts is their flexibility in terms of the nature of the problems addressed and stakeholders involved. This is likely to generate variability in directions when comes the time to prioritise issues, to define respective roles and responsibilities and to articulate local health contracts with other instruments of governance on a given territory (Jabot and Laurent, Reference Jabot and Laurent2018).

At the crossroads of primary care and public health, the primary health care approach seeks to extend the scope of primary care services to meet public health goals at the meso level in order to improve community health (Levesque et al., Reference Levesque, Breton, Senn, Levesque, Bergeron and Roy2013). The meso level shows how professionals, civil society organisations and communities can interact to strengthen the ‘primary care’ that delivers care at the micro level (De Maeseneer et al., Reference De Maeseneer, Aertgeerts, Remmen and Devroey2014). We postulate that local health contracts can be potentially designed as instruments to foster primary healthcare at the meso level. This could facilitate linkages between health professionals and public health ones together around the community’s needs.

Overall, the expected structuration of integrated professional community-based care sets a context increasing the likeliness of collaboration between primary care and public health at the local level (Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé, 2019a), but the extent to which local health contracts may stand as instruments for this convergence remains under-documented (Breton and Team CLoterreS, Reference Breton2020).

In this context, our objective was to investigate the involvement of primary care professionals in local health contracts, more specifically, we examined (1) whether and how frequently primary care actors were involved in local health contracts; (2) how primary care professionals were involved; and (3) in what type of public health actions primary care actors collaborated with local partners.

Methods

This exploratory study was conducted as an offspring of the CLoterreS research project. For this project, with the guidance of international guidelines, the CLoterreS team has developed a database of local health contracts. For each contract, the database includes information, for example, on the main health issues to be addressed on the territory, on the affiliations of the signatories of the contract, on the themes addressed in each action plan, be these related to the social determinants of health, health promotion activities, disease prevention activities and health care services.

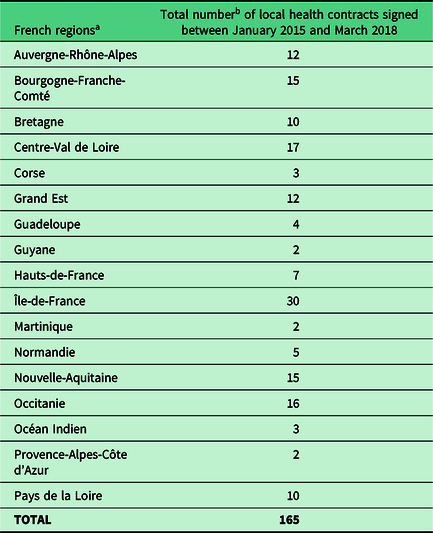

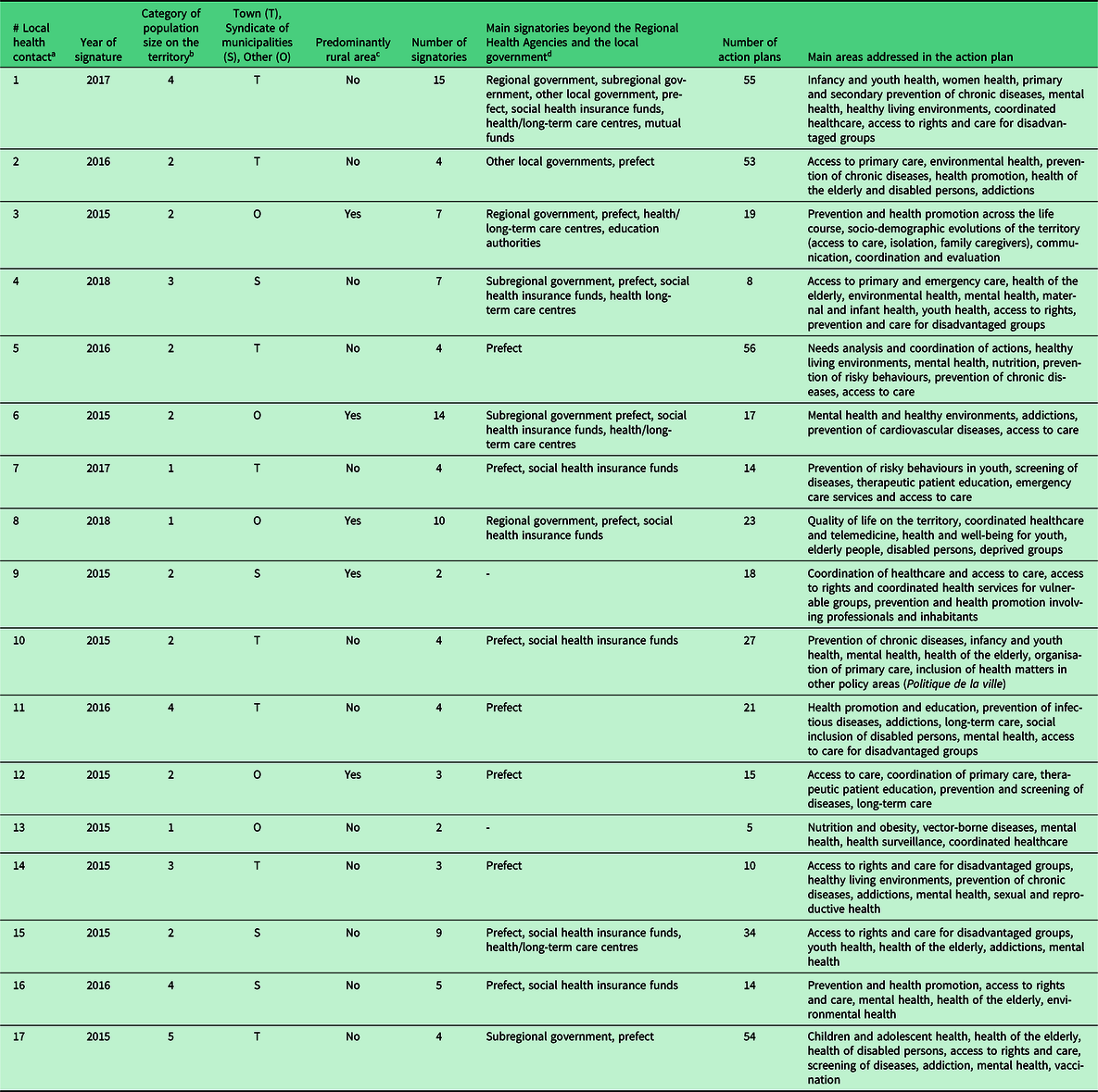

An observational documentary analysis on the signed contracts was conducted between January 2018 and June 2018. This study is based on a stratified sample of 17 local health contracts (one per French region) randomly selected from the population of 165 contracts signed between January 2015 and March 2018 inventoried through the CLoterreS research project (Table 1). Although the first local health contract dates back from 2011, the CLoterreS team selected this period to reflect current practices and better inform decisions. To be eligible, the full contract (terms and action plan) had to be available in the CLoterreS database in November 2018. Considering the variety of regional policies and territories across the country, this strategy proved instrumental in providing a diversity of cases (Table 2) rather than a representative sample of all local health contracts.

Table 1. National census of local health contracts (source: CLoterreS project)

a Names corresponding to the 17 Regional Health Agencies in 2018.

Table 2. General characteristics of the sample of 17 local health contracts included in the study (source: CLoterreS project)

a Random numbering, independent from the numbers associated with the 17 French regions as shown in Table 1.

b Categories (number of inhabitants): (1) < 10 000; (2) 10 000–50 000; (3) 50 000–100 000; (4) 100 000–500 000; (5) > 500 000.

c Territory covered by the local health contract corresponding predominantly (or not) to a rural area (Pays, PETR, parc naturel).

d Prefect: (sub-) regional state representative and its services.

Material analysed

A local health contract takes the form of a document whose structure usually reflects the template suggested by the Ministry of Health (Agence Régionale de Santé, 2018). It covers sections such as context, identification and engagement of partners and a list of action plans. An action plan includes a thematic title, a statement of the general objective, a statement of its specific objectives, a description of the actions, partners who contributed to design the action plan, the actors involved to implement the actions, budget, timeline and evaluation objectives. In practice, due to the local context, the methodological resources and actors’ configuration, there are variations between and within local health contracts. For instance, while a contract may feature 5 action plans, another one may have 50. The period that covers the contract also varies and so the number and characteristic of partners for each action plan.

Dataset and analysis

A dataset in Excel format was created, and the coding was carried out at the action plan level for each of the 17 contracts. From the 17 contracts, we retrieved 440 action plans. Insufficient information on 12 of them brought the number of plans down to 428.

In order to analyse whether and how frequently primary care professionals were involved in the local health contracts, we first created a nominal variable to identify the presence of primary care professional’s involvement. Two researchers (CK and YB) coded the actions as follows and reached a consensus when disagreeing: the action (1) includes the involvement of a primary care professional or organisation; (0) does not include any primary care professional or organisation; (99) includes a health care professional but primary care professional is not mentioned specifically. Primary care actions were defined by the involvement of professionals or health care organisations, which were identified through a set of keywords (see Appendix 1). As an example of keywords, a multiprofessional primary care practice (maison de santé pluriprofessionnelle; MSP) is a grouping of different primary care professionals (general practitioner, nurse, physiotherapist, midwife and others) usually practicing in the same venue but not necessarily. For the qualitative analysis of the data, the actions that involve primary care were retrieved and thematic analysis was performed against the involvement of primary care professionals:

-

In order to identify the nature of the involvement of primary care professionals in the local health contracts, we carried out a thematic analysis of each action plan. We followed an inductive approach by allowing iterative revisions during the coding. These responsibilities could range from being a leader or partner in developing the action plan or being the actual target of the action. In order to perform this coding, we reviewed the whole action plans rather than relying only on how such responsibilities were described in a specific box of the plan.

-

In order to analyse the nature of public health actions involving primary care professionals in the local health contracts, we used two sources as a starting point (WHO The 10 Essential PublicHealth Operations, 2019). These sources are the WHO Essential Public Health operations and the French law on public health actions for primary care professionals (Code de la santé publique - Article L6323-3). Following these, we adopted a deductive-inductive approach by allowing ourselves to modify our classification in light of the material analysed. At the end of this process, we created our final nominal variables as (1) coordination of care, (2) health protection including environmental occupational, food safety and others, (3) health promotion including actions to address the social determinants of health and health inequity, (4) disease prevention including early detection of illness, (5) patient education programs, (6) access to care. When needed, double coding was applied.

Following the thematic analysis, a descriptive analysis was done at the action plan level (n = 428) and at the contract level (n = 17) by using Microsoft Excel version 16.02 and SPSS 15.0 software.

Results

The mean number of action plans per local health contract was 25±17.58 (min-max = 5–55, median = 19). Amongst the 428 action plans analysed, 20.1% (n = 86) included at least one component involving primary care providers, 28.5% (n = 122) involving some kind of health care providers, that is, primary care professionals not specifically mentioned. In Figure 1, we show the presence of primary care professionals in each local health contract.

-

i. The nature of primary care professionals’ involvement

Figure 1. Presence of primary care involvement in the local health contracts.

Amongst all actions that involve specifically primary care professionals or organisations (n = 86), 5 actions (6%) were discarded for lack of information on the nature of professional involvement, leaving 81 action plans for the analyses.

-

a. Primary care professionals are rarely the action leader (9%, n = 7)

In very few cases, primary care professionals stood as leaders of the action. When they did, they were either mentioned as being the main person/organisation in charge of the action or, co-heading the development of the action plan and its implementation. Here are two examples:

‘Objective of the action: Improve access to health care administrative rights for vulnerable population

Actions planned:

-

- Provide financial and fundamental support to multiprofessional primary care projects to support their actions in the priority districts for urban policy

-

- Support teams of practicing health professionals in the development and implementation of their health project

Leaders of the action: Regional Health Agencies, city and an association of health professionals’ (FA. 6.51.)

‘Objective of the action: Sustain primary care services by creating health centres

Actions planned:

-

- Guarantee access to primary healthcare for the population of [name of territory] through the presence of three multiprofessional primary care practices

-

- Establish multiprofessional primary care teams which will be the foundation of each health centres

-

- Formalize a health project for each health centre, by self-employed health professionals, validated by the Regional Health Agencies

Leader of the action: Community, Association of Multiprofessional primary care practice (…)’ (FA.9.11.)

-

a. Primary care professionals are sometimes action partner (25%, n = 20)

As illustrated in the following extracts of two local health contracts, when the primary care professionals were the partner of the action, they were not stated as leaders of the action, but they had an active role in its development and implementation. In this category, we also identified actions that include primary care organisations as a partner but not necessarily professionals of the region themselves.

‘Objective of the action: To allow the inhabitants of the territory to have rapid access to an ophthalmological examination within the validated framework of the follow-up of diabetics

Actions planned:

-

- Tele-ophthalmology

Leader of the action: Ophthalmologists

Partners: Regional Health Agencies, local branch of social security, association of self-employed health professionals, general practitioners, nurses, health professional associations.’ (FA.3.4.)

In certain actions, even though primary care professionals were mentioned as a partner of the action, the text did not state their responsibilities.

‘Objective of the action: To improve vaccine coverage

Actions planned:

-

- UC-IRSA (regional social security organisation for prevention and health promotion) proposes to ensure that children are vaccinated during school registration in town hall and design a similar targeting system for active and inactive people who are unemployed, and who do not necessarily consult general practitioner.

-

- The UC-IRSA can travel to the site to organise sessions of vaccination drives as needed.

Leader of the action: UC-IRSA

Partners: Regional Health Agencies, local branch of social security, self-employed doctors, nurses, pharmacists, multiprofessional health practices, associations…’ (FA.4.6.)

-

a. Primary care professionals are mostly the target of the action (66%, n = 54)

For the majority of actions, primary care professionals were the target of the action. That means they did not have any responsibility in leading the action or developing it. They were little more than a channel to reach the target population.

‘Objective of the action: Fighting sedentary lifestyles as part of primary and secondary prevention, through the implementation of physical activities/ sports adapted to the target groups

Action planned:

-

- Creation of a network including family doctors, physical activity coach for people with a chronic disease, coordinator within the local government supporting the project, sports educator of a local sports association. Each protagonist will be associated to the network through a formal agreement. A training component specific to the “Prescription of Sport” project for sports educators is included in the scheme.

Leader of the action: City of (…).

Partners: not mentioned’ (FA.15.4.10.)

‘Objective: To improve familiarity and promote respite care for family carers and elderly people

Action planned:

-

- Prioritize the establishment of medical services (health centres or others) in town centres in order to facilitate the accessibility of these services to elderly people whose mobility is reduced

Leader of the action: Regional Health Agencies and Departmental Council, co-management with the support of the project team (Gerontology association, Health Cooperation Group).’ (FA.13.3.)

-

i. Type of actions that involve primary care professionals

Amongst the actions involving primary care providers (n = 86), 76.7% (n = 66) aimed to promote access to healthcare. The breakdown of actions whether they include an access-to-care action for each local health contract is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Number of action plans that include (or not) access-to-care actions, amongst all actions which involve primary care professionals.

Amongst access-to-care actions (n = 66), 28.8% (n = 19) were about access to preventive services, 27.3% (n = 18) about coordination to increase access to other care services, particularly to specialised care, 22.7% (n = 15) about access to primary care services in general, 15.2% (n = 10) about access to health promotive services excluding health education and 6.0% (n = 4) were about access to patient education. For example:

‘Objective of the action: Maintain access to primary care services and continuity of care

Actions planned:

-

- Organisation of meetings with general practitioners in order to address the difficulties they face and create a dynamic for a joint project

Type of action: Access to care (primary care services) (FA.1.2.1.)’

‘Objective of the action: Promote telemedicine projects by facilitating and improving patient pathways with a better coordination between health professionals and allowing habitants to access to health care services

Actions planned:

-

- Setting up of a mobile unit for telemedicine services via videoconference in general practice clinics

Type of action: Access to care (specialised care services), coordination of care (FA.3.3.)’

The other actions involving primary care professionals without any access-to-care component (23.3%; n = 20) were limited to disease prevention, health promotion, coordination of care and health education. We did not find any health protection-related action involving primary care professionals or organisations such as one addressing environmental health.

‘Objective of the action: Train care providers and improve communication between providers of home-care services

Actions planned:

-

- Train care providers about good use of existing resources in order to improve comprehensiveness and utility of shared information between general practitioners and other home care providers

Type of action: Coordination of care (FA.4.10.)’

‘Objective of the action: Improve the quality of life of children, adolescents and young adults in the territory

Actions planned:

-

- Carry out a half day of exchange with professionals from the neighbourhood around the factors (biological, social, cultural, etc.) that determine a child’s weight gain. Will also be discussed:

-

○ their knowledge and their perceptions in terms of food hygiene

-

○ the needs they identify in this regard in the territory

-

Type of action: Health promotion (FA.6.6.)’

Discussion

Our study shows that primary care professionals or organizations have been involved in at least one out of five action plans in the local health contracts studied. Only a few actions were developed under the leadership of a primary care professional or organisation. The majority of actions included primary care professionals or their settings as a means to reach the target population. The majority of actions involving primary care focused on the dimension related to the accessibility of care services, sometimes including public health actions. Besides this, coordination, disease prevention and health promotion actions (without access to care) also included primary care providers, but only marginally.

Many action plans sought to involve primary care professionals. This may be difficult to do in practice, as primary care providers are mostly independent and private providers in France. As the French Government recently set a goal of developing nationally a 1000 communities of health care professionals (Communauté professionnelle territoriale de santé) by 2020, a figure that would represent a twofold increase in multiprofessional primary care practices (Safon, Reference Safon2018), and comes with the development of coordinative functions and roles, local health contracts could contribute in strengthening integration for the development of these initiatives by allowing increased access to care and prevention (Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé, 2019b).

The majority of action plans position primary care professionals as a target with very few descriptions of mechanisms to involve them. In some actions, we found the professional associations as partners of the actions. Yet, we do not have information on the nature of the relationship with the practice and involvement of regional health professionals in the project. Several scholars discuss the importance of developing common objectives and a shared vision for a successful collaboration between public health and primary care (Valaitis and Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement, Reference Valaitis2013; Pratt et al., Reference Pratt, Gyllstrom, Gearin, Lange, Hahn, Baldwin, VanRaemdonck, Nease and Zahner2018, Reference Pratt, Gyllstrom, Gearin, Hahn, VanRaemdonck, Peterson and Baldwin2017). In a Canadian study accounting for micro-, meso- and macro-level actors of collaboration, it was discussed that such collaboration sharing common objectives should occur at all levels, from top management to practicing professionals (Akhtar-Danesh et al., Reference Akhtar-Danesh, Valaitis, O’Mara, Austin and Munroe2013). This brings to attention the importance of normative function of collaboration such as developing joint missions and the need for developing initial and continuous education regarding collaboration amongst both public health and primary care professionals besides the development of functional enablers.

As regards the type of actions primary care providers are involved in, our analysis points to few linkages between primary care and public health actions in local health contracts. Beyond access to care, the involvement of primary care professionals in public health action plans is rather limited. We found that most action plans involving primary care were oriented towards improving access to care. Additionally, we found actions on the coordination function of primary care, which also increases access to specialist care. Today, a primary health care approach is accepted as a key for universal health access (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2019). Indeed, accessibility is one of the biggest contributions of primary care to population health improvement (Starfield et al., Reference Starfield, Shi and Macinko2005). This highlights the key role local level governance play in making universal health coverage effective even when it is written in the law of the land (Bourgueil, Reference Bourgueil2018). Accessibility remains a topical issue in France and elsewhere. This is an issue fuelled by a shortage of medical doctors and also the inadequacy of health care organisation to the changing health needs at the local level (DREES, 2012; WHO, 2016).

We found no action on the social determinants of health or health protection that involve primary care professionals or organisations. Although it is not explicitly one of the missions of the primary care professionals in France, we believe this could also either be explained by our small sample size or the lack of details about the nature of health care professionals mentioned. Indeed, the significant role of primary care in prevention is supported in the literature (Green et al., Reference Green, Brancati and Albright2012). We see more and more active involvement of primary care professionals in the health promotion and health protection areas such as environmental health issues (WONCA Working Party on the environment et al., 2019).

The number of instances of participation of primary care professionals or organisations was not linked to the type of actions but more to the local health contract itself. We noticed that there are clusters of actions that involve primary care professionals more frequently in some territories than others. This probably reflects the existing relations between local public health partners and primary care providers in certain local areas. This could be interpreted as a contribution of local health contracts as a means for further integrative instruments.

Finally, one should note that the local health contracts analysed stand as projects whose implementation is planned over a few years. This raises the question of their operationalisation and sustainability in the long term. Additionally, the issue of resource limitation should be acknowledged. As there is no specific budget attached to local health contracts’ implementation, funding decisions by Regional Health Agencies (and evolving national and regional priorities) are likely to impact decisions on which action plans get the priority at the local level. Thus, the leadership of the Regional Health Agencies, which are under national control, should be accounted for.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study investigating the involvement of primary care professionals in local health contracts. Thus, it is also the first attempt to identify the typology of actions that involve primary care in the local health contracts in the context of France.

Yet, the study has a number of limitations. First of all, we had a small sample size of local health contracts due to time constraints. However, based on a clustered random sampling method, our sample is diverse, that is, each local health contract was retrieved from a different French region thus providing an overview of the national landscape.

Another limitation was the identification of primary care actions in order to create the study dataset. As the contracts were from different French regions, the glossary of terms was not stabilised. In order to standardise, we defined keywords a priori to classify the primary care actions (Appendix 1). We also only coded actions when they clearly referred to primary care professionals, organisations or associations. But, by adopting this approach, we probably limited the number of actions considered in the analysis. We likely underestimated the frequency of primary care involvement, which may be between 20 and 48% of actions if we assume that the health care professionals that are not specifically mentioned as primary care professionals could include primary care.

Lastly, the material of the study was made of documents describing actions planned, not actual actions implemented. Additionally, the degree of precision of each action plan varied significantly. As a salient example, in one contract, an action plan was detailed in five pages whereas, in another one, several action plans with different themes were combined in one page. With no information on the actual implementation of the plans, there is a possibility that some may never see the light of the day. Still, our study provides valuable indications on the involvement of primary care professionals and organisations in public health actions at the local level, which is an important first step towards primary healthcare.

Conclusion

French local health contracts involve primary care providers in at least one-fifth of action plans, mostly based on their accessibility to care and coordination functions, not only at the individual level but also within population-centred action plans.

There is obviously room to further develop community-oriented actions of primary care at the local level. This could be taken into account in order to reinforce local health contracts as a promising primary health care strategy in the context of actual policy with the current development of integrated professional community-based care.

One way to improve the collaboration between primary care and public health could be strengthening the role of primary care as a partner of the public health actions. This includes the development of a joint vision and of missions, goals and objectives amongst different actors at the local level. Much has to be done to operationalise closer collaboration such as improving training and continuous education for health professionals and creating specific positions for public health professionals in the management of projects. Hence, more empirical work is needed to identify cases of successful collaboration at the local level and their contributing factors. Due to the strong policy will to implement rapid changes, interventional research and action research may be an appropriate strategy.

Financial support

The authors Candan Kendir and Yann Bourgueil received funding by Mission RESPIRE. Mission RESPIRE was funded by French School of Public Health, French National Health Insurance Fund for Employees and French Institute for Research and Information in Health Economics (EHESP-CNAMTS-IRDES – EA MOS 7348 EHESP). CLoterreS was funded through the 2016 general grant cycle of the French Public Health Institute (IRePS: BRETON-AAP16-PREV-16). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Appendix 1. Keywords for primary care providers or organisations

-

« Soins primaires » Primary care;

-

« Soins de premier recours » Primary care;

-

« Soins de première ligne » Primary care;

-

« Soins de proximité » Community-based care;

-

« Médecin généraliste » General practitioner;

-

« Médecin traitant » Family doctor/ Family physician;

-

« Infirmières » Nurse;

-

« Sage-femme » Midwife;

-

« Pharmacien » Pharmacist;

-

« Laboratoire » Laboratorian;

-

« Dentiste » Dentist;

-

« Maison de santé pluriprofessionelle » Multiprofessional health practices;

-

« Maison de santé » Multiprofessional health centres;

-

« Pôle de santé » Health centres;

-

« Maison de santé pluriprofessionelle universitaire » Universitary Multiprofessional health practices;

-

« SAMU » Emergency health care services.

Appendix 2. Definition of public health actions