Introduction

Two patients suffering from the same mental disorder may show differences in symptom expression, behavior, and pathophysiology. Case-control research paradigms ignore these sources of heterogeneity; they assume that each diagnostic group is a distinct entity. A key goal in many such studies is to identify biological markers that are reliable indicators of disease state. However, markers identified through this approach generally explain only a small part of the variance linked to mental disorders (Schmaal et al., Reference Schmaal, Veltman, van Erp, Sämann, Frodl, Jahanshad, Loehrer, Tiemeier, Hofman, Niessen, Vernooij, Ikram, Wittfeld, Grabe, Block, Hegenscheid, Völzke, Hoehn, Czisch, Lagopoulos, Hatton, Hickie, Goya-Maldonado, Krämer, Gruber, Couvy-Duchesne, Rentería, Strike, Mills, de Zubicaray, McMahon, Medland, Martin, Gillespie, Wright, Hall, MacQueen, Frey, Carballedo, van Velzen, van Tol, van der Wee, Veer, Walter, Schnell, Schramm, Normann, Schoepf, Konrad, Zurowski, Nickson, McIntosh, Papmeyer, Whalley, Sussmann, Godlewska, Cowen, Fischer, Rose, Penninx, Thompson and Hibar2016; Hibar et al., Reference Hibar, Westlye, Doan, Jahanshad, Cheung, Ching, Versace, Bilderbeck, Uhlmann, Mwangi, Krämer, Overs, Hartberg, Abe, Dima, Grotegerd, Sprooten, Ben, Jimenez, Howells, Delvecchio, Temmingh, Starke, Almeida, Goikolea, Houenou, Beard, Rauer, Abramovic, Bonnin, Ponteduro, Keil, Rive, Yao, Yalin, Najt, Rosa, Redlich, Trost, Hagenaars, Fears, Alonso-Lana, van Erp, Nickson, Chaim-Avancini, Meier, Elvsashagen, Haukvik, Lee, Schene, Lloyd, Young, Nugent, Dale, Pfennig, McIntosh, Lafer, Baune, Ekman, Zarate, Bearden, Henry, Simhandl, McDonald, Bourne, Stein, Wolf, Cannon, Glahn, Veltman, Pomarol-Clotet, Vieta, Canales-Rodriguez, Nery, Duran, Busatto, Roberts, Pearlson, Goodwin, Kugel, Whalley, Ruhe, Soares, Fullerton, Rybakowski, Savitz, Chaim, Fatjó-Vilas, Soeiro-de-Souza, Boks, Zanetti, Otaduy, Schaufelberger, Alda, Ingvar, Phillips, Kempton, Bauer, Landén, Lawrence, van Haren, Horn, Freimer, Gruber, Schofield, Mitchell, Kahn, Lenroot, Machado-Vieira, Ophoff, Sarró, Frangou, Satterthwaite, Hajek, Dannlowski, Malt, Arolt, Gattaz, Drevets, Caseras, Agartz, Thompson and Andreassen2017; Hoogman et al., Reference Hoogman, Bralten, Hibar, Mennes, Zwiers, Schweren, van Hulzen, Medland, Shumskaya, Jahanshad, de Zeeuw, Szekely, Sudre, Wolfers, Onnink, Dammers, Mostert, Vives-Gilabert, Kohls, Oberwelland, Seitz, Schulte-Rüther, Ambrosino, Doyle, Høvik, Dramsdahl, Tamm, van Erp, Dale, Schork, Conzelmann, Zierhut, Baur, McCarthy, Yoncheva, Cubillo, Chantiluke, Mehta, Paloyelis, Hohmann, Baumeister, Bramati, Mattos, Tovar-Moll, Douglas, Banaschewski, Brandeis, Kuntsi, Asherson, Rubia, Kelly, Di Martino, Milham, Castellanos, Frodl, Zentis, Lesch, Reif, Pauli, Jernigan, Haavik, Plessen, Lundervold, Hugdahl, Seidman, Biederman, Rommelse, Heslenfeld, Hartman, Hoekstra, Oosterlaan, von Polier, Konrad, Vilarroya, Ramos-Quiroga, Soliva, Durston, Buitelaar, Faraone, Shaw, Thompson and Franke2017). Therefore, the case-control paradigm has been challenged in recent years. For example, large international initiatives aim to bridge the gap between a psychiatric diagnosis and its underlying biology through the integration of information across multiple dimensions (Insel, Reference Insel2009; Insel et al., Reference Insel, Cuthbert, Garvey, Heinssen, Pine, Quinn, Sanislow and Wang2010; Schumann et al., Reference Schumann, Binder, Holte, de Kloet, Oedegaard, Robbins, Walker-Tilley, Bitter, Brown, Buitelaar, Ciccocioppo, Cools, Escera, Fleischhacker, Flor, Frith, Heinz, Johnsen, Kirschbaum, Klingberg, Lesch, Lewis, Maier, Mann, Martinot, Meyer-Lindenberg, Müller, Müller, Nutt, Persico, Perugi, Pessiglione, Preuss, Roiser, Rossini, Rybakowski, Sandi, Stephan, Undurraga, Vieta, van der Wee, Wykes, Haro and Wittchen2014), yielding subgroups of patients stratified based on behavior (Fair et al., Reference Fair, Nigg, Iyer, Bathula, Mills, Dosenbach, Schlaggar, Mennes, Gutman, Bangaru, Buitelaar, Dickstein, Di Martino, Kennedy, Kelly, Luna, Schweitzer, Velanova, Wang, Mostofsky, Castellanos and Milham2013; Mostert et al., Reference Mostert, Hoogman, Onnink, van Rooij, von Rhein, van Hulzen, Dammers, Kan, Buitelaar, Norris and Franke2015) or biological functioning (Marquand et al., Reference Marquand, Wolfers, Mennes, Buitelaar and Beckmann2016b). While such stratification approaches may produce more homogeneous diagnostic groups, these approaches still do not fully inform on how patients differ from one another in terms of the underlying biology. Therefore, inter-individual differences become a novel research focus (Foulkes and Blakemore, Reference Foulkes and Blakemore2018; Seghier and Price, Reference Seghier and Price2018).

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a prevalent and impairing neurodevelopmental disorder, which persists into adulthood in a substantial part of the patients (Simon et al., Reference Simon, Czobor, Balint, Meszaros and Bitter2009). Reliable group differences between healthy individuals and those with ADHD have been established for various biological readouts (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Valera and Seidman2005; Seidman et al., Reference Seidman, Valera and Makris2005; Valera et al., Reference Valera, Faraone, Murray and Seidman2007; Cortese and Castellanos, Reference Cortese and Castellanos2012; van Ewijk et al., Reference van Ewijk, Heslenfeld, Zwiers, Buitelaar and Oosterlaan2012; van Rooij et al., Reference van Rooij, Hartman, Mennes, Oosterlaan, Franke, Rommelse, Heslenfeld, Faraone, Buitelaar and Hoekstra2015; Wolfers et al., Reference Wolfers, van Rooij, Oosterlaan, Heslenfeld, Hartman, Hoekstra, Beckmann, Franke, Buitelaar and Marquand2016). These include neuroimaging-based brain readouts, where differences in gray matter volume, white matter volume, as well as functional brain readouts (Frodl and Skokauskas, Reference Frodl and Skokauskas2012; Onnink et al., Reference Onnink, Zwiers, Hoogman, Mostert, Kan, Buitelaar and Franke2014; Faraone et al., Reference Faraone, Asherson, Banaschewski, Biederman, Buitelaar, Ramos-Quiroga, Rohde, Sonuga-Barke, Tannock and Franke2015; Greven et al., Reference Greven, Bralten, Mennes, O'Dwyer, Van Hulzen, Rommelse, Schweren, Hoekstra, Hartman, Heslenfeld, Oosterlaan, Faraone, Franke, Zwiers, Arias-Vasquez and Buitelaar2015; Wolfers et al., Reference Wolfers, Onnink, Zwiers, Arias-Vasquez, Hoogman, Mostert, Kan, Slaats-Willemse, Buitelaar and Franke2015b, Reference Wolfers, Llera, Onnink, Dammers, Hoogman, Zwiers, Buitelaar, Franke, Marquand and Beckmann2017; Francx et al., Reference Francx, Llera, Mennes, Zwiers, Faraone, Oosterlaan, Heslenfeld, Hoekstra, Hartman, Franke, Buitelaar and Beckmann2016; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Carlisi, Lukito, Hart, Mataix-Cols, Radua and Rubia2016) have been reported. However, these differences are mostly of small to medium effect size and have not readily translated into individualized predictions (Wolfers et al., Reference Wolfers, Buitelaar, Beckmann, Franke and Marquand2015a). In line with this observation, evidence accumulated in the last decades points towards ADHD being characterized by a high degree of heterogeneity (Faraone et al., Reference Faraone, Asherson, Banaschewski, Biederman, Buitelaar, Ramos-Quiroga, Rohde, Sonuga-Barke, Tannock and Franke2015): More specifically, individuals with ADHD can differ from each other in their symptom profiles (clinical heterogeneity), their exposure to environmental stressors (environmental heterogeneity), and the underlying biology of their disorder (biological heterogeneity). This complexity, and the rather exclusive research focus on a categorical diagnosis, has hindered progress towards a better understanding of ADHD (Burmeister et al., Reference Burmeister, McInnis and Zöllner2008; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Daly and O'Donovan2012). Moreover, the developmental character of ADHD has been shown in numerous studies, and differences in brain development and aging have been observed across the lifespan (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Eckstrand, Sharp, Blumenthal, Lerch, Greenstein, Clasen, Evans, Giedd and Rapoport2007; Greven et al., Reference Greven, Bralten, Mennes, O'Dwyer, Van Hulzen, Rommelse, Schweren, Hoekstra, Hartman, Heslenfeld, Oosterlaan, Faraone, Franke, Zwiers, Arias-Vasquez and Buitelaar2015; Hoogman et al., Reference Hoogman, Bralten, Hibar, Mennes, Zwiers, Schweren, van Hulzen, Medland, Shumskaya, Jahanshad, de Zeeuw, Szekely, Sudre, Wolfers, Onnink, Dammers, Mostert, Vives-Gilabert, Kohls, Oberwelland, Seitz, Schulte-Rüther, Ambrosino, Doyle, Høvik, Dramsdahl, Tamm, van Erp, Dale, Schork, Conzelmann, Zierhut, Baur, McCarthy, Yoncheva, Cubillo, Chantiluke, Mehta, Paloyelis, Hohmann, Baumeister, Bramati, Mattos, Tovar-Moll, Douglas, Banaschewski, Brandeis, Kuntsi, Asherson, Rubia, Kelly, Di Martino, Milham, Castellanos, Frodl, Zentis, Lesch, Reif, Pauli, Jernigan, Haavik, Plessen, Lundervold, Hugdahl, Seidman, Biederman, Rommelse, Heslenfeld, Hartman, Hoekstra, Oosterlaan, von Polier, Konrad, Vilarroya, Ramos-Quiroga, Soliva, Durston, Buitelaar, Faraone, Shaw, Thompson and Franke2017). Therefore, the importance of modeling ADHD across the lifespan has become increasingly apparent (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Shaw, Lerch, Lerch, Greenstein, Greenstein, Sharp, Sharp, Clasen, Clasen, Evans, Evans, Giedd, Giedd, Castellanos, Castellanos, Rapoport and Rapoport2006; Hoogman et al., Reference Hoogman, Bralten, Hibar, Mennes, Zwiers, Schweren, van Hulzen, Medland, Shumskaya, Jahanshad, de Zeeuw, Szekely, Sudre, Wolfers, Onnink, Dammers, Mostert, Vives-Gilabert, Kohls, Oberwelland, Seitz, Schulte-Rüther, Ambrosino, Doyle, Høvik, Dramsdahl, Tamm, van Erp, Dale, Schork, Conzelmann, Zierhut, Baur, McCarthy, Yoncheva, Cubillo, Chantiluke, Mehta, Paloyelis, Hohmann, Baumeister, Bramati, Mattos, Tovar-Moll, Douglas, Banaschewski, Brandeis, Kuntsi, Asherson, Rubia, Kelly, Di Martino, Milham, Castellanos, Frodl, Zentis, Lesch, Reif, Pauli, Jernigan, Haavik, Plessen, Lundervold, Hugdahl, Seidman, Biederman, Rommelse, Heslenfeld, Hartman, Hoekstra, Oosterlaan, von Polier, Konrad, Vilarroya, Ramos-Quiroga, Soliva, Durston, Buitelaar, Faraone, Shaw, Thompson and Franke2017). For example, individually different growth trajectories of different brain regions may be an important aspect of this complex phenotype (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Shaw, Lerch, Lerch, Greenstein, Greenstein, Sharp, Sharp, Clasen, Clasen, Evans, Evans, Giedd, Giedd, Castellanos, Castellanos, Rapoport and Rapoport2006, Reference Shaw, Eckstrand, Sharp, Blumenthal, Lerch, Greenstein, Clasen, Evans, Giedd and Rapoport2007).

In this study, we aimed to quantify and map the brain structural heterogeneity in adults with persistent ADHD, at the level of the individual patient. We employed a normative modeling approach for this purpose, which provides a perspective that is fundamentally different from the classic case-control approach. A normative model can be understood as a statistical model that maps demographic, behavioral, or any other variable to -for example- a quantitative brain read-out (Marquand et al., Reference Marquand, Rezek, Buitelaar and Beckmann2016a), whilst providing estimates of centiles of variation within the population. Then, the individual can be placed within the normative range, allowing for the characterization of differences between individual patients in relation to the healthy range. In this way, we (i) chart the heterogeneity in abnormalities of brain structure at the level of the individual with ADHD, and (ii) investigate the degree of spatial overlap in terms of deviations from the normative model to provide concrete estimates for disorder heterogeneity. Based on previous case-control comparisons (e.g. Onnink et al., Reference Onnink, Zwiers, Hoogman, Mostert, Kan, Buitelaar and Franke2014; Faraone et al., Reference Faraone, Asherson, Banaschewski, Biederman, Buitelaar, Ramos-Quiroga, Rohde, Sonuga-Barke, Tannock and Franke2015; Greven et al., Reference Greven, Bralten, Mennes, O'Dwyer, Van Hulzen, Rommelse, Schweren, Hoekstra, Hartman, Heslenfeld, Oosterlaan, Faraone, Franke, Zwiers, Arias-Vasquez and Buitelaar2015; Wolfers et al., Reference Wolfers, Onnink, Zwiers, Arias-Vasquez, Hoogman, Mostert, Kan, Slaats-Willemse, Buitelaar and Franke2015b, Reference Wolfers, Llera, Onnink, Dammers, Hoogman, Zwiers, Buitelaar, Franke, Marquand and Beckmann2017; Francx et al., Reference Francx, Llera, Mennes, Zwiers, Faraone, Oosterlaan, Heslenfeld, Hoekstra, Hartman, Franke, Buitelaar and Beckmann2016), which introduced the notion of the ‘average ADHD patient’, we expected participants with ADHD to show on average larger negative deviations from the normative brain ageing model than healthy individuals. More importantly, we anticipated that the individual local deviance from the normative model would differ substantially between individuals, suggesting that previous group-level distinctions provide an incomplete picture of the neurobiological abnormalities in ADHD and disguise extreme inter-individual differences between individuals with ADHD.

Methods

Participants

We selected adult participants with persistent ADHD and healthy individuals from the Dutch cohort of the International Multicenter persistent ADHD CollaboraTion (IMpACT; Hoogman et al., Reference Hoogman, Aarts, Zwiers, Slaats-Willemse, Naber, Onnink, Cools, Kan, Buitelaar and Franke2011; Mostert et al., Reference Mostert, Hoogman, Onnink, van Rooij, von Rhein, van Hulzen, Dammers, Kan, Buitelaar, Norris and Franke2015), based on data availability for structural MRI images. Participants with persistent ADHD were recruited from the Department of Psychiatry of the Radboud University Medical Center and through advertisements. In this recruitment process, the participants with persistent ADHD were matched for gender, age, and estimated intelligence to a healthy individual population. All participants underwent psychiatric assessments, neuropsychological testing, and neuroimaging. The diagnostic interview for persistent ADHD (DIVA; Sandra Kooij et al., Reference Sandra Kooij, Marije Boonstra, Swinkels, Bekker, De Noord and Buitelaar2008) was conducted to confirm the diagnosis of ADHD in adulthood. This interview focuses on the 18 DSM-IV symptoms of ADHD and uses realistic examples to thoroughly investigate whether a symptom is currently present or was already present in childhood (Sandra Kooij et al., Reference Sandra Kooij, Marije Boonstra, Swinkels, Bekker, De Noord and Buitelaar2008). In all participants in the ADHD cohort, a childhood history of ADHD symptoms was established, and persistent ADHD was diagnosed. The ADHD Rating Scale-IV was filled in by each participant to report current symptoms of attention and hyperactivity/impulsivity (Pappas, Reference Pappas2006). To assess comorbidities, the structured clinical interviews (SCID-I and SCID-II) for DSM-IV were administered (van Groenestijn et al., Reference van Groenestijn, Akkerhuis, Kupka, Schneider and Nolen1999; Weertman et al., Reference Weertman, Arntz, Dreessen, van Velzen and Vertommen2003; Lobbestael et al., Reference Lobbestael, Leurgans and Arntz2011). The inclusion criteria for participants with ADHD were: (i) DSM-IV-TR criteria for ADHD met in childhood as well as in adulthood, (ii) no psychosis, (iii) no substance use disorder, (iv) full-scale intelligence estimate >70 (prorated from Block Design and Vocabulary of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2012), (v) no neurological disorders, (vi) no obvious sensorimotor disabilities, (vii) no medication use other than psychostimulants or atomoxetine. Additional inclusion criteria for healthy individuals were: (viii) no current neurological or mental disorder according to DIVA, SCID-I, or SCID-II, (ix) no first-degree relatives with ADHD or other major mental disorders. All participants were Dutch and of European Caucasian ancestry. This study was approved by the regional ethics committee (Centrale Commissie Mensgebonden Onderzoek: CMO Regio Arnhem – Nijmegen; Protocol number III.04.0403). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

MRI acquisition

Whole brain imaging was performed using a 1.5 T scanner (Magnetom Avanto, Siemens Medical Systems) with a standard 8-channel head coil. A high-resolution T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid-acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) anatomic scan was obtained from each participant, in which the inversion time (TI) was chosen to provide optimal gray matter–white matter T1 contrast [repetition time (TR) 2730 ms, echo time (TE) 2.95 ms, TI 1000 ms, flip angle 7°, field of view (FOV) 256 × 256 × 176 mm3, voxel size 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm3]. The T1 images served as a basis for the extraction of gray and white matter volumes.

Estimation of gray and white matter volume

Prior to gray matter volume estimation, all participants’ T1 images were rigidly aligned using statistical parametric mapping version 12 (SPM-12). Subsequently, images were segmented, normalized, and bias field–corrected using ‘new segment’ from SPM12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm; Ashburner and Friston, Reference Ashburner and Friston2000, Reference Ashburner and Friston2005) yielding images containing gray and white matter segments. We then used DARTEL (Ashburner, Reference Ashburner2007) to create a study-specific gray matter template to which all segmented images were normalized. Subsequently, all gray matter volumes were smoothed with an 8-mm full width half maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel, and the normative model was estimated.

Normative modeling

The normative modeling method employed here is described in the supplemental methods (Marquand et al., Reference Marquand, Rezek, Buitelaar and Beckmann2016a). Briefly, normative models were estimated using Gaussian process regression (Rasmussen and Williams, Reference Rasmussen and Williams2006), a Bayesian non-parametric interpolation method that yields coherent measures of predictive confidence in addition to point estimates. This is important, as we used this uncertainty measure to quantify both the centiles of variation within the cohort and the deviation of each patient from the group mean at each specific brain locus. In this way, we were able to statistically quantify deviations from the normative model with regional specificity, by computing a Z-score for each voxel, reflecting the difference between the predicted volume and the true volume normalized by the uncertainty of the prediction (Marquand et al., Reference Marquand, Rezek, Buitelaar and Beckmann2016a). Thus, we quantified extreme positive and negative deviations (reflecting increased or decreased volume, respectively) from the normative model using a reasonable threshold for the resulting z-statistic. In the present study, we estimated normative brain changes across the adult lifespan represented in our study (Fig. 1) using Gaussian process regression to predict regional gray and white matter volumes across the brain from age and sex. The normative range for this model in healthy individuals was estimated using 10-fold cross-validation, then we applied the model trained on all healthy individuals to participants with ADHD.

Fig. 1. In (a), the estimation of the normative model in healthy individuals is depicted using age and gender as covariates. In (b), the characterization of the normative model is shown. We see that the normative model changes with age and that, from age 20 to 70 years, gray matter is predominantly decreasing; this is true for both females and males and more strongly observed in frontal brain regions. Blue colors indicate a decrease, red colors an increase. In (c), we depict the application of the normative model to persistent ADHD. In (d), we present the steps that were taken to characterize the deviations from the normative model.

First, we assessed group-level deviations from the normative model. For this, individual gray and white matter deviation maps were fed into PALM (Permutation Analysis of Linear Model; Winkler et al., Reference Winkler, Webster, Vidaurre, Nichols and Smith2015), which allowed for permutation-based inference. We estimated mean group-level deviations from the normative model in healthy individuals and in patients with ADHD. PALM creates a map of z-values for each of these groups. We thresholded these group maps using Z = ± 2.6, to assist comparisons with the individual maps of deviation described below. Further, we report the contrasts for participants with persistent ADHD and healthy individuals corrected for false discovery rate (FDR) at the 5% inference level using threshold-free cluster enhancement.

Next, the individual maps of deviation were thresholded at |Z| > 2.6. These maps reflect the deviation from the normative model at the individual level. Note that the use of a fixed statistical threshold across participants allows for a simplified comparison between participants in terms of numbers of extreme deviation from the normative model, even when the overall distribution of deviations of a participant is shifted. We also repeated the analyses correcting for multiple comparisons at the individual participant level using the Benjamini and Hochberg procedure (Benjamini and Hochberg, Reference Benjamini and Hochberg1995). This did not change our conclusions. Extreme positive deviations were defined as all voxels with a value higher than Z > 2.6, while extreme negative deviations are defined as a value below the Z < −2.6. All extreme deviations were combined into scores representing the percentage of extreme positive and extreme negative deviations for each participant. We tested for associations between diagnosis and those scores using a non-parametric χ2 test in a general linear model. We corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni-Holm method (Holm, Reference Holm1979). We created individualized maps of extreme deviations and calculated the voxel-wise overlap between individuals from the same groups. In a final analysis, we tested for associations between the percentage of extremely deviating voxels and age, symptom scores, and comorbidity. We corrected for the number of correlations (8) and modality using the Bonferroni-Holm method (Holm, Reference Holm1979). All analyses were performed in python3.6 (www.python.org).

Results

Participants

Table 1 shows the demographics of the study population. We included 153 adults with ADHD and 146 healthy adults. About the same proportion of individuals in both groups were male (43.8% first and 41.2% second group, respectively). The average age of participants was 35 years in both groups with an age distribution that was very similar (online Supplementary Fig. S1). Individuals with persistent ADHD showed higher scores than healthy individuals for hyperactivity-impulsivity (5.45 v. 0.63; t test: p < 0.01) as well as inattention (7.27 v. 0.55; t test: p < 0.01).

Table 1. Demographics and clinical characteristics

a ADHD diagnosis was based on a structured Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults (DIVA; Sandra Kooij et al., Reference Sandra Kooij, Marije Boonstra, Swinkels, Bekker, De Noord and Buitelaar2008).

b Estimated intelligence was based on the block-design and vocabulary subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-III; Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2012).

c DIVA hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms in adults.

d DIVA inattention symptoms in adults.

e Number of comorbid disorders such as major depressive disorder based on a SCID (Structured Clinical Interview) interview (van Groenestijn et al., Reference van Groenestijn, Akkerhuis, Kupka, Schneider and Nolen1999; Weertman et al., Reference Weertman, Arntz, Dreessen, van Velzen and Vertommen2003; Lobbestael et al., Reference Lobbestael, Leurgans and Arntz2011)

Normative model

Figure 1a, c and d show a high-level visual summary of the analysis procedure. Figure 1b depicts a spatial representation of the voxel-wise normative model. This model was characterized by global gray matter decreases from age 20 to 70 years, with the largest decreases primarily in frontal and cerebellar regions, which is in line with the typical decline of gray matter volume over age (Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Dahnke, Lutz, Yotter and Gaser2012; Farokhian et al., Reference Farokhian, Yang, Beheshti, Matsuda and Wu2017). This was true for females and males, which we modeled separately due to the presence of sex effects in ADHD (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Walters, Demontis, Mattheisen, Lee, Robinson, Brikell, Ghirardi, Larsson, Lichtenstein, Eriksson, Werge, Mortensen, Pedersen, Mors, Nordentoft, Hougaard, Bybjerg-Grauholm, Wray, Franke, Faraone, O'Donovan, Thapar, Børglum and Neale2018). In contrast, the normative model for the white matter was characterized by both decreases and increases across adulthood. More specifically, parietal and temporal brain regions showed an increase with age, areas in frontal and in particular thalamic regions showed decreased, in both sexes. This is in line with earlier reports on healthy aging (Farokhian et al., Reference Farokhian, Yang, Beheshti, Matsuda and Wu2017). In online Supplementary Fig. S2, we depict the mean deviation of the normative model across all ages separately for females and males.

Characterization of mean deviations from the normative model

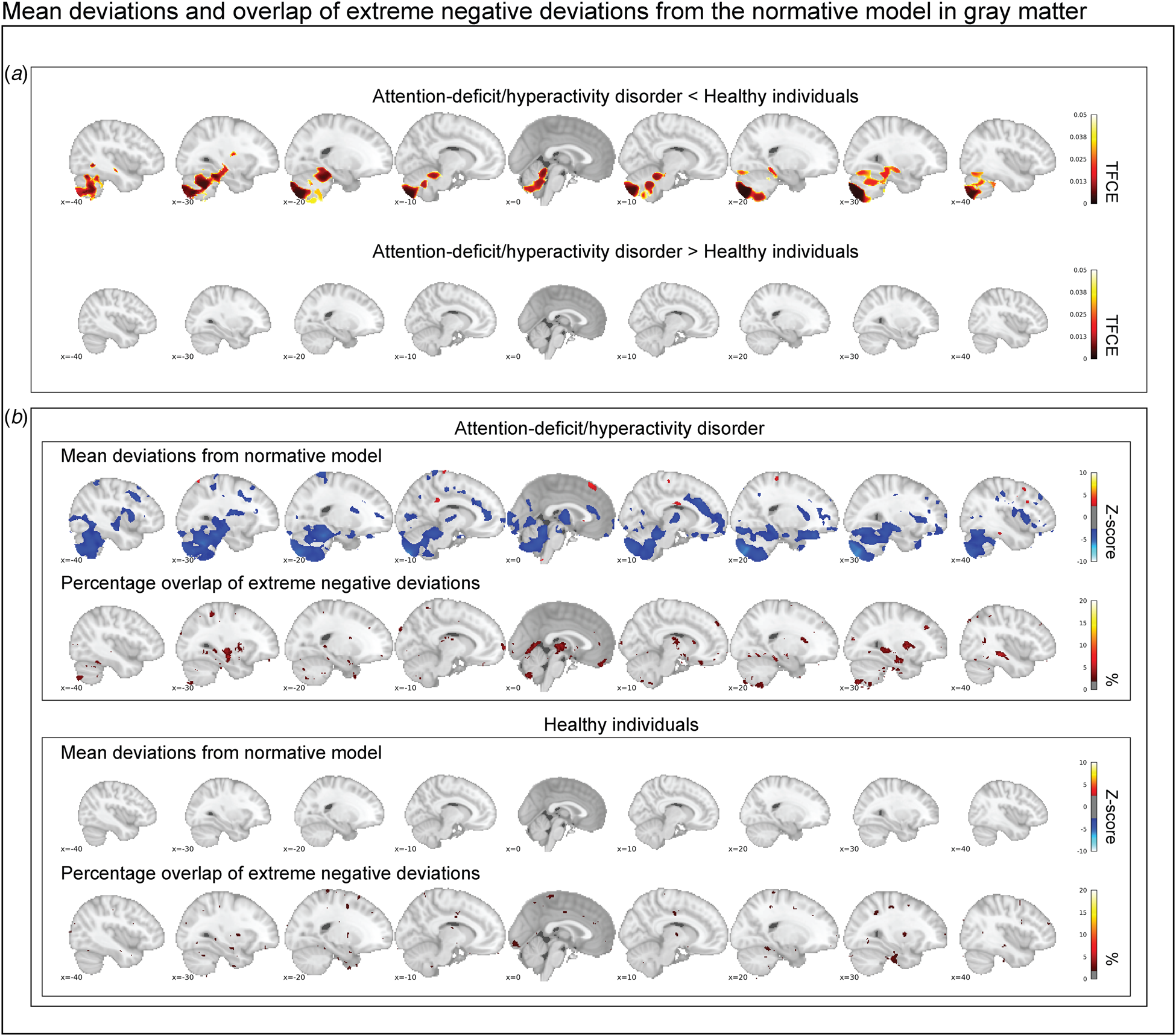

Figure 2a shows the mean deviations from the normative model in the gray matter for healthy individuals and those with ADHD. Individuals with ADHD and healthy individuals differed significantly after correction for multiple comparisons in their mean deviations from the normative model in the cerebellum, temporal brain regions, and the hippocampus. Participants with ADHD on average showed larger mean negative deviations in those regions. Looking at Z-score maps thresholded at ±2.6, this pattern was confirmed, and additional regions showing negative mean deviations were observed in the anterior cingulate, insula, and frontal cortex (Fig. 2b). No differences in mean deviations between patients and controls were observed in white matter (online supplementary Fig. S3a), although some positive and negative mean deviations exceeded the z-score threshold of ±2.6 in patients: for instance, temporal brain regions showed positive deviations, while frontal and parietal regions showed negative deviations (online Supplementary Fig. S3b).

Fig. 2. In (a), the contrast between persistent ADHD and healthy individuals is depicted corrected at a false discovery rate of 5%. Cerebellar regions, temporal regions, and the hippocampus deviate significantly in gray matter. In (b), the group-level mean deviations of participants with persistent ADHD and healthy individuals are depicted (|Z| < 2.6) and compared with the overlap maps of extreme negative deviations (Z < −2.6). In summary, while we reproduce prominent group-level differences between healthy individuals and participants with persistent ADHD, we observe that extreme negative deviations are hardly present in more than 2% of the individuals with persistent ADHD in those brain regions.

Association of extreme deviations from the normative model with persistent ADHD

An analysis of the total percentage of extreme negative deviations in gray matter across the groups showed that participants with persistent ADHD differed significantly from healthy individuals (Wald χ2(1) = 23.64, p corr. < 0.001). This effect was driven by a larger percentage of negative deviations in participants with persistent ADHD (0.48%; 95% confidence interval 0.30–0.66%) than in healthy individuals (0.28%; 95% confidence interval 0.24–0.34%). In white matter, significant differences in the percentage of extreme negative deviations were observed between groups as well (Wald χ2(1) = 18.02, p corr. < 0.001); again, a significantly higher proportion of negative deviations was seen in participants with persistent ADHD (0.41%; 95% confidence interval 0.24–0.57%) than in healthy individuals (0.24%; 95% confidence interval 0.17–0.31%). No differences between groups were observed in positive deviations on measures in gray and white matter (online Supplementary Table S1). As only the percentage of extreme negative deviations were significant between individuals with persistent ADHD and healthy participants we focus our characterizations of those deviations on extreme negative deviations in gray matter, we report the other extreme deviations in different modalities in the supplement but report the main outcomes in the section below as well.

Characterization of extreme negative deviations from the normative model

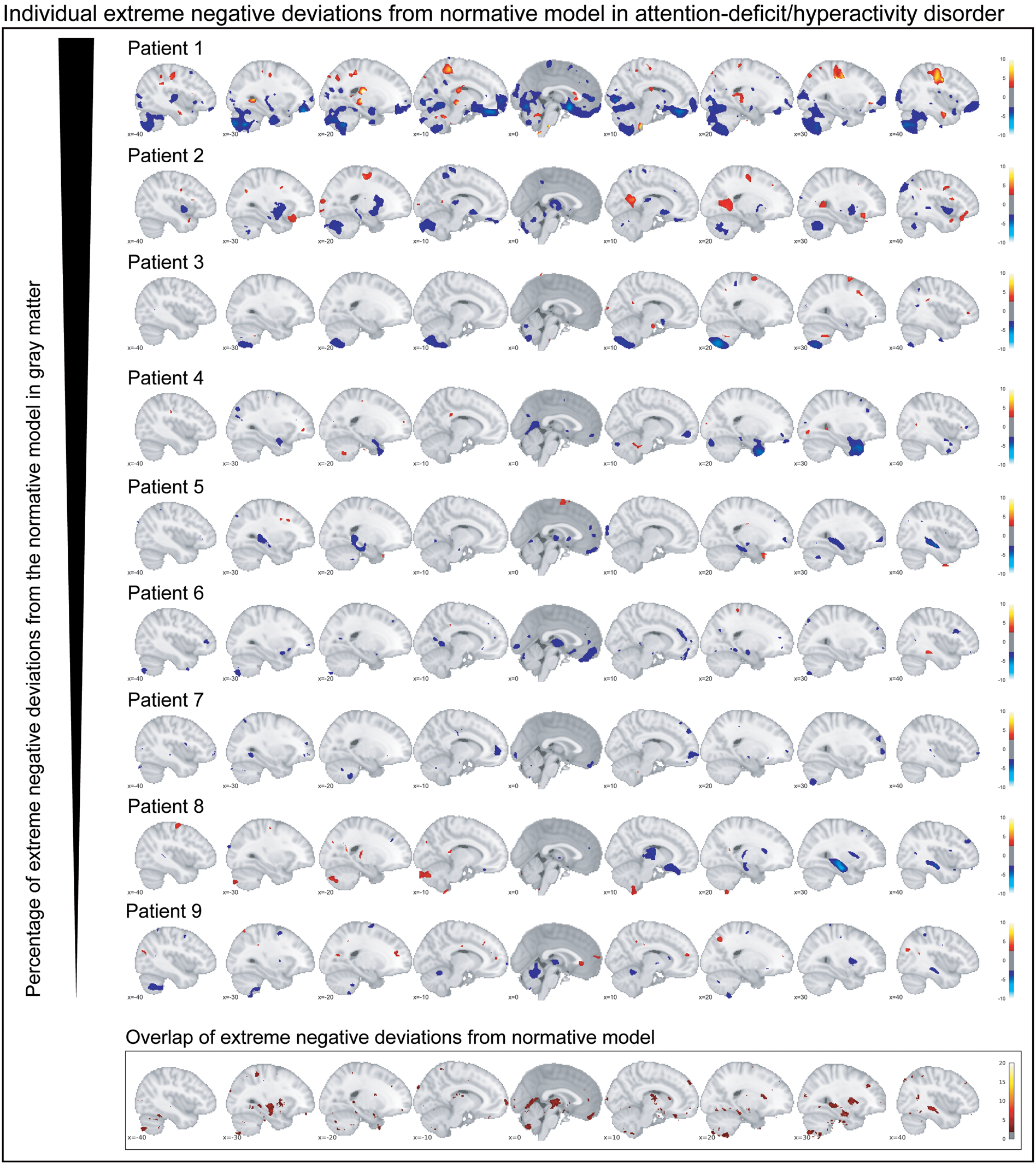

Participants with ADHD showed overlap in local gray matter negative deviations in more than 2% of patients primarily in the cerebellum, hippocampus, and basal ganglia; less overlap in negative deviations was observed in healthy individuals (Fig. 2b). In white matter, we also observed greater overlap in participants with ADHD than in healthy individuals, again involving regions around the hippocampus and the basal ganglia (online supplementary Fig. S3b). A scattered pattern of positive deviations was seen in the (online supplementary Fig. S4) overlap maps for participants with ADHD as well as for healthy individuals in both gray and white matter. The overlap maps of the extreme negative deviations partly resembled the pattern observed in the mean deviation analyses of cases and controls (Fig. 2b), also when detecting extreme deviation based on the FDR (online Supplementary Fig. S5). Further, nine out of the ten most negatively deviating patients showed extreme values in the cerebellum (Fig. 3), although in non-overlapping areas. Generally, deviations in both positive and negative directions were unique for each participant with ADHD in gray and white matter, when looking at the patterns of individual deviations, with limited overlap (online Supplementary Fig. S6). The extreme negative deviations were associated with age in participants with ADHD (β-weight = 0.198, p = 0.014), but not symptom scores, stimulant medication, or comorbidity, before correction for multiple comparisons (online Supplementary Table S1); for the extreme positive deviations, we did not find any associations that were even nominally significant.

Fig. 3. The individual extreme negative deviations from the normative model in gray matter are depicted for participants with persistent ADHD. Below the corresponding overlap map in gray matter is depicted. In summary, individual extreme deviations show a very unique pattern across participants with persistent ADHD.

Discussion

We mapped the biological heterogeneity of persistent ADHD in reference to normative brain aging across the adult lifespan, based on voxel-based morphometry derived brain measures. In participants with ADHD, we observed robust mean deviations in gray matter from the normative model in the cerebellum, temporal regions, and the hippocampus. However, at the individual level, we found that few brain loci showed extreme negative deviations in more than 2% of the participants with ADHD, providing a measure for the (substantial) inter-individual variation between adults with persistent ADHD.

Case-control comparisons show small to medium effect sizes of (gray matter) alterations in adult ADHD patients (Frodl and Skokauskas, Reference Frodl and Skokauskas2012; Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Dahnke, Lutz, Yotter and Gaser2012; Hoogman et al., Reference Hoogman, Bralten, Hibar, Mennes, Zwiers, Schweren, van Hulzen, Medland, Shumskaya, Jahanshad, de Zeeuw, Szekely, Sudre, Wolfers, Onnink, Dammers, Mostert, Vives-Gilabert, Kohls, Oberwelland, Seitz, Schulte-Rüther, Ambrosino, Doyle, Høvik, Dramsdahl, Tamm, van Erp, Dale, Schork, Conzelmann, Zierhut, Baur, McCarthy, Yoncheva, Cubillo, Chantiluke, Mehta, Paloyelis, Hohmann, Baumeister, Bramati, Mattos, Tovar-Moll, Douglas, Banaschewski, Brandeis, Kuntsi, Asherson, Rubia, Kelly, Di Martino, Milham, Castellanos, Frodl, Zentis, Lesch, Reif, Pauli, Jernigan, Haavik, Plessen, Lundervold, Hugdahl, Seidman, Biederman, Rommelse, Heslenfeld, Hartman, Hoekstra, Oosterlaan, von Polier, Konrad, Vilarroya, Ramos-Quiroga, Soliva, Durston, Buitelaar, Faraone, Shaw, Thompson and Franke2017). Here, we show that some of these differences between participants with ADHD and healthy individuals in normative gray matter deviations are consistent with these earlier case-control findings. Note that our approach differs as we modeled the healthy range prior to computing group-level differences on the basis of deviations from normative aging. That said, mean normative differences in hippocampus and temporal region overlap with regions that have earlier been identified in children with ADHD (Hoogman et al., Reference Hoogman, Bralten, Hibar, Mennes, Zwiers, Schweren, van Hulzen, Medland, Shumskaya, Jahanshad, de Zeeuw, Szekely, Sudre, Wolfers, Onnink, Dammers, Mostert, Vives-Gilabert, Kohls, Oberwelland, Seitz, Schulte-Rüther, Ambrosino, Doyle, Høvik, Dramsdahl, Tamm, van Erp, Dale, Schork, Conzelmann, Zierhut, Baur, McCarthy, Yoncheva, Cubillo, Chantiluke, Mehta, Paloyelis, Hohmann, Baumeister, Bramati, Mattos, Tovar-Moll, Douglas, Banaschewski, Brandeis, Kuntsi, Asherson, Rubia, Kelly, Di Martino, Milham, Castellanos, Frodl, Zentis, Lesch, Reif, Pauli, Jernigan, Haavik, Plessen, Lundervold, Hugdahl, Seidman, Biederman, Rommelse, Heslenfeld, Hartman, Hoekstra, Oosterlaan, von Polier, Konrad, Vilarroya, Ramos-Quiroga, Soliva, Durston, Buitelaar, Faraone, Shaw, Thompson and Franke2017). In addition, we observed mean normative deviations in the cerebellum; a decreased gray matter was seen in individuals with ADHD across the adult lifespan. The cerebellum is of increasing interest in ADHD (Berquin et al., Reference Berquin, Giedd, Jacobsen, Hamburger, Krain, Rapoport and Castellanos1998): for example, in case-control studies, those with ADHD have shown a decreased size of the cerebellum (Carmona et al., Reference Carmona, Vilarroya, Bielsa, Trèmols, Soliva, Rovira, Tomàs, Raheb, Gispert, Batlle and Bulbena2005; Ivanov et al., Reference Ivanov, Murrough, Bansal, Hao and Peterson2014), which may be linked to timing problems that are present across many individuals with this disorder (Aase and Sagvolden, Reference Aase and Sagvolden2005). We do not observe a robust difference in the prefrontal cortex or basal ganglia, regions that have often been implicated in (childhood) ADHD (Faraone and Biederman, Reference Faraone and Biederman1998; Frodl and Skokauskas, Reference Frodl and Skokauskas2012). However, when reducing thresholding in the group-level maps (|Z| > 2.6), these regions do present reductions in gray matter volume also in the current study (Fig. 2).

Whilst the group-level results based on normative deviations described above are largely in line with existing ADHD literature and point to the cerebellum as an important structure in persistent ADHD, we additionally observe a large biological heterogeneity at the level of the brain. Specifically, we found that only a few individual brain loci showed extreme negative deviations in more than 2% of the participants with ADHD, providing quantitative evidence of the biological heterogeneity of persistent ADHD (Faraone et al., Reference Faraone, Asherson, Banaschewski, Biederman, Buitelaar, Ramos-Quiroga, Rohde, Sonuga-Barke, Tannock and Franke2015) and showing that inter-individual differences at the level of brain structure are a hallmark for this phenotype. This is consistent with conceptual developments such as the Research Domain Criteria (Insel et al., Reference Insel, Cuthbert, Garvey, Heinssen, Pine, Quinn, Sanislow and Wang2010), which emphasize the importance of moving beyond simple group comparisons in psychiatry towards multilevel, high-dimensional descriptions of individual patients. Our finding that patients with persistent ADHD differ substantially on an individual level speaks against the concept of the ‘average ADHD patient’ and suggests that it does not sufficiently reflect the degree of inter-individual variation that characterizes this disorder. This may explain why case-control studies, which dominate research on ADHD and mental disorders in general, have shown small group differences between patients and healthy individuals (Franke et al., Reference Franke, Neale and Faraone2009; Hamshere et al., Reference Hamshere, Langley, Martin, Agha, Stergiakouli, Anney, Buitelaar, Faraone, Lesch, Neale, Franke, Sonuga-Barke, Asherson, Merwood, Kuntsi, Medland, Ripke, Steinhausen, Freitag, Reif, Renner, Romanos, Romanos, Warnke, Meyer, Palmason, Vasquez, Lambregts-Rommelse, Roeyers, Biederman, Doyle, Hakonarson, Rothenberger, Banaschewski, Oades, McGough, Kent, Williams, Owen, Holmans, O'Donovan and Thapar2013; Onnink et al., Reference Onnink, Zwiers, Hoogman, Mostert, Kan, Buitelaar and Franke2014; Faraone et al., Reference Faraone, Asherson, Banaschewski, Biederman, Buitelaar, Ramos-Quiroga, Rohde, Sonuga-Barke, Tannock and Franke2015; Greven et al., Reference Greven, Bralten, Mennes, O'Dwyer, Van Hulzen, Rommelse, Schweren, Hoekstra, Hartman, Heslenfeld, Oosterlaan, Faraone, Franke, Zwiers, Arias-Vasquez and Buitelaar2015; Wolfers et al., Reference Wolfers, Onnink, Zwiers, Arias-Vasquez, Hoogman, Mostert, Kan, Slaats-Willemse, Buitelaar and Franke2015b, Reference Wolfers, Llera, Onnink, Dammers, Hoogman, Zwiers, Buitelaar, Franke, Marquand and Beckmann2017; Francx et al., Reference Francx, Llera, Mennes, Zwiers, Faraone, Oosterlaan, Heslenfeld, Hoekstra, Hartman, Franke, Buitelaar and Beckmann2016). We expect a high degree of inter-individual differences for other biological readouts (e.g. functional measures) but quantifying the degree and mapping the nature of such heterogeneity is an important topic of future research.

Voxel-based morphometry studies are fundamentally reductionist, comparing group differences on the voxel by voxel level, making strong assumptions on (i) a single locus contributing to a disorder and (ii) group homogeneity. This approach has been extended by pattern classification studies, which consider multiple voxels at once and show that using structural MRI the predictions of ADHD range from about 60% to up to about 90% accuracy indicating a high variability between studies (Bansal et al., Reference Bansal, Staib, Laine, Hao, Xu, Liu, Weissman, Peterson and Zhan2012; Igual et al., Reference Igual, Soliva, Escalera, Gimeno, Vilarroya and Radeva2012; The ADHD 200 consortium, 2012; Lim et al., Reference Lim, Marquand, Cubillo, Smith, Chantiluke, Simmons, Mehta and Rubia2013; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Lin, Zhang and Wang2013; Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Mwangi, Matthews, Coghill, Konrad and Steele2014; Wolfers et al., Reference Wolfers, Buitelaar, Beckmann, Franke and Marquand2015a). A prime example, the ADHD-200 competition, in which ADHD was predicted on the basis of different brain read-outs, showed predictions that did not exceed 60% accuracy (The ADHD 200 consortium, 2012). These outcomes were replicated in follow-up research, summarized in different reviews and studies using all kinds of brain imaging readouts (Sabuncu and Konukoglu, Reference Sabuncu and Konukoglu2014; Wolfers et al., Reference Wolfers, Buitelaar, Beckmann, Franke and Marquand2015a, Reference Wolfers, van Rooij, Oosterlaan, Heslenfeld, Hartman, Hoekstra, Beckmann, Franke, Buitelaar and Marquand2016, Reference Wolfers, Llera, Onnink, Dammers, Hoogman, Zwiers, Buitelaar, Franke, Marquand and Beckmann2017). Here, we used mass-univariate predictions, similar to voxel-based morphometry. However, unlike this approach we did not assume homogenous groups of individuals with ADHD and healthy participants. While this assumption is fundamental in voxel-based morphometry, it is also essential for pattern classification approaches. The present results question this assumption.

The present results allow for a novel interpretation of earlier large-scale pattern recognition studies in ADHD, which often showed relatively low accuracy in discriminating ADHD cases from controls (Wolfers et al., Reference Wolfers, Buitelaar, Beckmann, Franke and Marquand2015a). In larger studies, the predictive accuracy for ADHD is reduced relative to smaller studies, which is counterintuitive to the premises of general machine learning, where an increase in sample size usually improves learning from data (Hastie et al., Reference Hastie, Tibshirani and Friedman2009). This conundrum can be understood in the context of the present results, as larger, more representative samples capture more of the biological as well as procedural heterogeneity (e.g. due to different scanners sites) of this disorder. Therefore, a larger sample will provide a better estimate of the variation between individuals. This increases the difficulty to find a common decision function across participants with ADHD in pattern classification analyses. Note, however, that larger studies also deal, to a greater extent with for instance acquisition inhomogeneities across different scanners, which might affect predictions negatively, while smaller studies may be more carefully controllable, or just by chance select a more homogenous subgroup.

We are confident that the present results and the main conclusions are replicable in follow-up studies. However, a few limitations require a discussion. First, we had to use 10-fold cross-validation in healthy individuals and out of sample predictions in individuals with persistent ADHD, as our healthy sample was too small to split it into two. This potentially introduces a small bias. Second, we did not find associations of symptom scores with the percentage of deviation from the normative model. However, the measures we used to assess symptoms rely on self-report, which is generally noisier than measures from diagnostic interviews. Finally, our sample did not allow to inspect the effect of comorbidities and other potentially confounding factors on the obtained results as the comorbidities were inconsistent across individuals. In future studies, we envision that normative models are built on the basis of large population samples. These population-based normative models can subsequently be applied to cohorts that sample ADHD using the same inclusion criteria for healthy individuals as for those with a disorder. In this way normative modeling is complementary to classical case-control comparisons as it allows for the investigation of individual differences. Here, we show that an approach relying on case-control differences is not sufficient to understand ADHD and its biological heterogeneity.

In conclusion, while our group level effects are largely in line with existing literature on ADHD, our approach also shows that the disorder is a much more biologically heterogeneous on the individual level than previously anticipated. We thus need to move towards descriptions of biology for the individual patient to improve our understanding of ADHD. The present results provide the first quantitative estimate of the degree of biological heterogeneity, in terms of spatial overlap of an individual's extreme gray and white matter deviations, linked to ADHD. In this way, we provide valuable information to improve the nosology and characterization of the different facets of persistent ADHD.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719000084.

Author ORCIDs

Thomas Wolfers, 0000-0002-7693-0621

Christian F. Beckmann, 0000-0002-3373-3193

Martine Hoogman, 0000-0002-1261-7628

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants that took part in this study. This study makes use of the data of the Dutch node of the IMpACT cohort, which was supported by a grant from the Brain & Cognition Excellence Program and a Vici grant (to Barbara Franke) from NWO (grant numbers 433-09-229 and 016-130-669), by the Netherlands Brain Foundation [grant number, 15F07(2)27], and BBMRI-NL (grant CP2010-33). Andre Marquand gratefully acknowledges support from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) via a Vernieuwingsimpuls VIDI fellowship (grant number 016.156.415). Christian F Beckmann received funding from a personal VIDI NWO grant (864-12-003) as well as the Wellcome Trust UK Strategic Award (098369/Z/12/Z). The research leading to these results also received funding from the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreements no. 602450 (IMAGEMEND), no. 602805 (Aggressotype), and no. 278948 (TACTICS). In addition, the project received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreements no. 643051 (Marie Sklodowska-Curie program; MiND) and no. 667302 (CoCA).

Conflict of interest

Barbara Franke has received educational speaking fees from Shire and Medice. Jan K. Buitelaar has been a consultant to/member of advisory board of and/or speaker for Janssen Cilag BV, Eli Lilly, Medice, Roche, and Servier. He is not an employee of any of these companies. He is not a stock shareholder of any of these companies. He has no other financial or material support, including expert testimony, patents, or royalties. Christian F Beckmann is director and shareholder of SBGneuro Ltd. The other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 and further that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guides on the care and use of laboratory animals.