Introduction

The Carboniferous sedimentary rocks of Mexico, which are globally recognized for their wide exposure and fossil content, crop out in different localities throughout the country. Four specific regions stand out: Chicomuselo, Chiapas (Torres-Martínez et al., Reference Torres-Martínez, Sour-Tovar and Barragán2016); central Sonora (Navas-Parejo, Reference Navas-Parejo2018); La Peregrina, Tamaulipas (Sour-Tovar et al., Reference Sour-Tovar, Álvarez and Martínez-Chacón2005); and Santiago Ixtaltepec, Oaxaca (Sour-Tovar, Reference Sour-Tovar1994). Each of these regions is characterized by wide geographical extension, successional layers, and high diversity in marine invertebrates (the last does not apply to the Santa Rosa Formation from Chiapas). Brachiopods are the most abundant and diverse phylum, but sponges, rugose corals, bivalves, gastropods, ammonoids, ostracodes, trilobites, bryozoans, and crinoids are also present. Other important taxonomic groups, such as benthic foraminifera and conodonts, are present as well (Navas-Parejo, Reference Navas-Parejo2018).

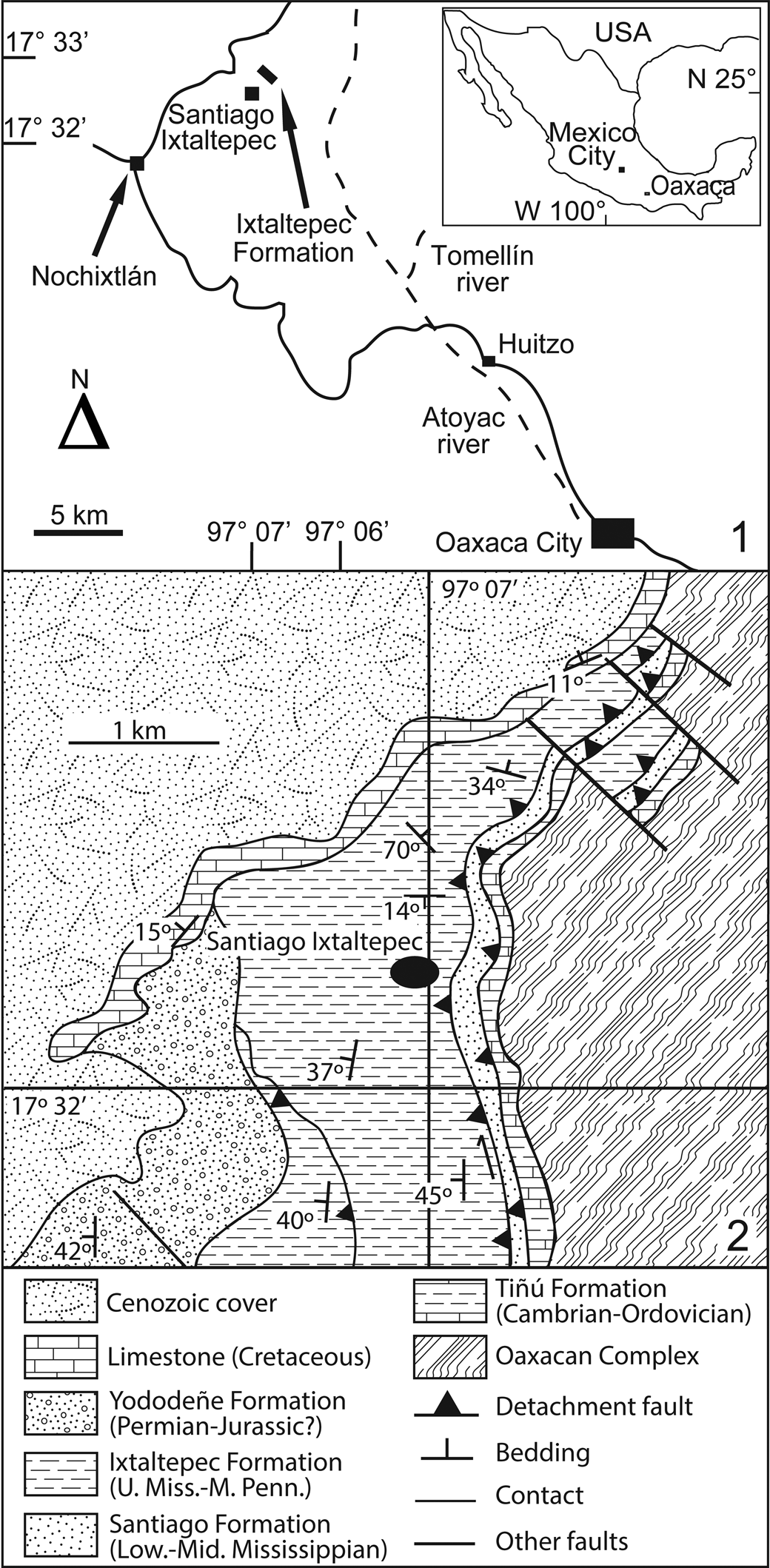

From these regions, it is in Santiago Ixtaltepec, Nochixtlán Municipality, Oaxaca, where one of the most complete Carboniferous successions of Mexico is exposed. Two formations are exposed there: the Santiago Formation from the Lower–Middle Mississippian, and the Ixtaltepec Formation from the Upper Mississippian–Middle Pennsylvanian (Fig. 1.1). Given that both units are predominantly made up of clastic rocks, their ages have been established by employing the different fossils found, such as bivalves (Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat, Reference Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat1998), ammonoids (Castillo-Espinoza, Reference Castillo-Espinoza2013), brachiopods (Pantoja-Alor, Reference Pantoja-Alor1970; Sour-Tovar and Martínez-Chacón, Reference Sour-Tovar and Martínez-Chacón2004; Torres-Martínez et al., Reference Torres-Martínez, Sour-Tovar and Pérez-Huerta2008, 2018; Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2012, 2016a, b, 2018), and crinoids (Villanueva-Olea et al., Reference Villanueva-Olea, Castillo-Espinoza, Sour-Tovar, Quiroz-Barroso and Buitrón-Sánchez2011; Villanueva-Olea and Sour-Tovar, Reference Villanueva-Olea and Sour-Tovar2014). For instance, the Ixtaltepec Formation was dated as Pennsylvanian (Pantoja-Alor, Reference Pantoja-Alor1970), after that as Bashkirian–Moscovian (=Morrowan–Desmoinesian) (Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat, Reference Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat1998; Sour-Tovar and Martínez-Chacón, Reference Sour-Tovar and Martínez-Chacón2004), and later as Serpukhovian (=Chesterian) and Bashkirian–Moscovian (Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2012, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2016a, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovarb). Likewise, these faunas have allowed correlation of the Oaxacan units with those recorded in other geographical regions, not only of North America but also globally as key components in the stratigraphical and paleogeographical works of the region.

Figure 1. Map of northwestern Oaxaca state, Mexico. (1) Geographic map of the Nochixtlán region showing the location of the Ixtaltepec Formation type section. (2) Simplified geological map of the Santiago Ixtaltepec area showing all lithostratigraphic units from the Paleozoic marine succession of Oaxaca.

Even though the Ixtaltepec Formation has been studied previously, there are still several poorly known taxa whose finds have allowed new and refined stratigraphical, paleoenvironmental, and paleogeographical interpretations. Therefore, this work aims to describe the rhynchonellid and spire-bearing brachiopods from the Ixtaltepec Formation, contributing to the discussion on the stratigraphical and paleogeographical significance of the Oaxacan brachiopod fauna from the Serpukhovian, Bashkirian, and Moscovian.

Geological setting

The Santiago Ixtaltepec region is in the Oaxaquian Geological Province (Fig. 1.2), and the stratigraphy of Paleozoic outcrops in this area is shown in Figure 2. The basement comprises metamorphic and metasedimentary rocks from the Oaxacan Complex, represented by Proterozoic gneiss and slate (Fries et al., Reference Fries, Schmitter, Damon and Livingstone1962; Solari et al., Reference Solari, Keppie, Ortega-Gutiérrez, Cameron, López and Hames2003). Overlying the Precambrian basement is the Tiñú Formation (Robison and Pantoja-Alor, Reference Robison and Pantoja-Alor1968), which is divided into two members: the inferior calcareous with upper Cambrian invertebrates; and the superior, mainly composed of Lower Ordovician shale with graptolites. The hiatus that divides both units is considered the Cambrian-Ordovician boundary (Sour-Tovar and Buitrón, Reference Sour-Tovar and Buitrón1987).

Figure 2. Stratigraphy of Paleozoic outcrops from Santiago Ixtaltepec area. The continuous thick black lines on each species indicate the fossiliferous units of the Ixtaltepec Formation where rhynchonellid and spire-bearing brachiopods were found. Thin black lines are guidelines connecting species names with occurrences. The thin dashed line between the two stratigraphic occurrences of Anthracospirifer occiduus indicates the absence of that species in API-3 and API-4, even though it is present in API-1 through API-3, API-5, and API-6.

Above the Tiñú Formation, two Carboniferous formations crop out (Pantoja-Alor, Reference Pantoja-Alor1970). The former is the Santiago Formation (Lower–Middle Mississippian) with a unit that currently is considered to be informal that is 164 m thick, followed by the Ixtaltepec Formation, which is ~560 m thick (Upper Mississippian–Middle Pennsylvanian). The base of the Carboniferous sequence (Santiago Formation) is composed of shallow marine facies of Tournaisian–Visean age (=Osagean) (Quiroz-Barroso et al., Reference Quiroz-Barroso, Pojeta, Sour-Tovar and Morales-Soto2000, Navarro-Santillán et al., Reference Navarro-Santillán, Sour-Tovar and Centeno-García2002), followed by Visean strata (=Meramecian) deposited in offshore environments (Sour-Tovar and Quiroz-Barroso Reference Sour-Tovar and Quiroz-Barroso1991; Castillo-Espinosa et al., Reference Castillo-Espinoza, Escalante-Ruiz, Quiroz-Barroso, Sour-Tovar and Navarro-Santillán2010). The stratigraphical transition to the Ixtaltepec Formation from the Serpukhovian–Moscovian (=Chesterian–Desmoinesian) is still unclear. Nonetheless, the occurrence of carbonate terrigenous facies representing shallow environments and reef patches in the lower strata of the Ixtaltepec Formation imply a hiatus at the base of the unit. The rest of the Ixtaltepec Formation is made up of alternating external marine and shallow-water environments that were subjected to tide changes (Torres-Martínez, Reference Torres-Martínez2014; Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2016a, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovarb; Hernández-Ocaña and Quiroz-Barroso, Reference Hernández-Ocaña and Quiroz-Barroso2018). Consequently, is possible to observe numerous changes in paleoenvironments (reef, peri-reef, lagoon, and offshore environments) throughout the stratigraphic unit. In some strata, it is possible that sea level reached the continental shore, as suggested by plant remains and supratidal ichnofossils (Hernández-Ocaña and Quiroz-Barroso, Reference Hernández-Ocaña and Quiroz-Barroso2018).

The Paleozoic succession ends with the Yododeñe Formation, which rests above the Ixtaltepec Formation and is composed of Permian–Triassic? conglomerate (Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2012). In addition, calcareous rocks from the Lower Cretaceous are exposed in the region (Sánchez-Beristain et al., Reference Sánchez-Beristain, García-Barrera and Moreno-Bedmar2019).

Ixtaltepec Formation fauna

The Ixtaltepec Formation is the unit with the most marine invertebrate diversity in the upper Paleozoic deposits of the Santiago Ixtaltepec area. Different groups have been described previously, including rugose corals (Peña-Salinas, Reference Peña-Salinas2014), bivalves (Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat, Reference Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat1997, Reference Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat1998), trilobites of the species Griffithides ixtaltepecensis Morón-Ríos and Perrilliat, Reference Morón-Ríos and Perrilliat1988, bryozoans (González-Mora and Sour-Tovar, Reference González-Mora and Sour-Tovar2014), ophiuroids (Quiroz-Barroso and Sour-Tovar, Reference Quiroz-Barroso and Sour-Tovar1995), and crinoids (calyxes and dissociated columnar ossicles) (Villanueva-Olea et al., Reference Villanueva-Olea, Castillo-Espinoza, Sour-Tovar, Quiroz-Barroso and Buitrón-Sánchez2011; Villanueva-Olea and Sour-Tovar, Reference Villanueva-Olea and Sour-Tovar2014).

Nonetheless, as noted above, brachiopods are the most common and abundant invertebrates. The fauna is represented by two subphyla (Linguliformea and Rhynchonelliformea), seven orders, 40 genera, and 64 species, the Order Productida being the most diverse group. The Order Lingulida is characterized by Orbiculoidea caneyana (Girty, Reference Girty1909), Orbiculoidea sp. Orbiculoidea missouriensis (Shumard and Swallow, Reference Shumard and Swallow1858), and Orbiculoidea capuliformis (McChesney, Reference McChesney1860) (Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2016b). The Order Productida is represented by the species Neochonetes (Neochonetes) granulifer (Owen, Reference Owen1852), Neochonetes (Neochonetes) mixteco Sour-Tovar and Martínez-Chacón, Reference Sour-Tovar and Martínez-Chacón2004 (Superfamily Chonetoidea); Semicostella sp., Antiquatonia sp. 1, Antiquatonia sp. 2, ?Keokukia sp., Productus concinnus Sowerby, Reference Sowerby1821, Weberproductus donajiae Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2016a, Desmoinesia aff. D. muricatina (Dunbar and Condra, Reference Dunbar and Condra1932), Inflatia inflata (McChesney, Reference McChesney1860), Inflatia coodzavuii Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2016a, Dictyoclostus transversum Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2016a, Reticulatia cf. R. huecoensis (King, Reference King1931), Buxtonia inexpletucosta Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2016a, Buxtonia websteri Beus and Lane, Reference Beus and Lane1969, Flexaria magna Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2016a, and an indeterminate Buxtoniini (Superfamily Productida); Echinoconchus zapoteco Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2012, Echinaria knighti (Dunbar and Condra, Reference Dunbar and Condra1932), Karavankina cf. K. fasciata (Kutorga, Reference Kutorga1844), Echinoconchella elegans (M'Coy, Reference M'Coy1844), Stegacanthia bowsheri Muir-Wood and Cooper, Reference Muir-Wood and Cooper1960 (Superfamily Echinoconchoidea); Linoproductus cf. L. prattenianus (Norwood and Pratten, Reference Norwood and Pratten1855), Linoproductus platyumbonus Dunbar and Condra, Reference Dunbar and Condra1932, Linoproductus sp., Marginovatia minor (Snider, Reference Snider1915), Marginovatia aureocollis Gordon and Henry, Reference Gordon and Henry1990, Marginovatia cf. M. pumila (Sutherland and Harlow, Reference Sutherland and Harlow1973), Cancrinella nunduva Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2012, Ovatia muralis Gordon, Reference Gordon1975, Nuanducosia sulcata Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2012, Undaria manxensis? Muir-Wood and Cooper, Reference Muir-Wood and Cooper1960, Martinezchaconia luisae Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2018 (Superfamily Linoproductoidea); and ?Sinuatella sp. from the Superfamily Aulostegoidea (Sour-Tovar and Martínez-Chacón, Reference Sour-Tovar and Martínez-Chacón2004; Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2012, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2016a, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2018; Torres-Martínez et al., Reference Torres-Martínez, Sour-Tovar, González-Mora and Barragán2018). In the Order Orthotetida are the species Orthotetes mixteca Sour-Tovar and Quiroz-Barroso, Reference Sour-Tovar and Quiroz-Barroso1989, Derbyia sp., and ?Schuchertella sp. (Sour-Tovar and Quiroz-Barroso, Reference Sour-Tovar and Quiroz-Barroso1989; Torres-Martínez et al., Reference Torres-Martínez, Sour-Tovar, González-Mora and Barragán2018), while in the Order Spiriferida are Neospirifer dunbari King, Reference King1933, Neospirifer pantojai Torres-Martínez, Sour-Tovar, and Pérez-Huerta, Reference Torres-Martínez, Sour-Tovar and Pérez-Huerta2008, Neospirifer amplia Torres-Martínez, Sour-Tovar, and Pérez-Huerta, Reference Torres-Martínez, Sour-Tovar and Pérez-Huerta2008, Septospirifer mazateca Torres-Martínez, Sour-Tovar, and Pérez-Huerta, Reference Torres-Martínez, Sour-Tovar and Pérez-Huerta2008, and ?Septospirifer sp. (Torres-Martínez et al., Reference Torres-Martínez, Sour-Tovar and Pérez-Huerta2008).

The species described in this work are included in the orders Rhynchonellida (Leiorhynchoidea perrilliatae n. sp., Leiorhynchoidea sp., Allorhynchus scientiana n. sp.), Athyridida (Composita ovata Mather, Reference Mather1915; Hustedia rotunda Lane, Reference Lane1962), Spririferida (Crurithyris expansa [Dunbar and Condra, Reference Dunbar and Condra1932]; an indeterminate Martiniid; Anthracospirifer occiduus [Sadlick, Reference Sadlick1960]; Anthracospirifer oaxacaensis n. sp., Anthracospirifer cf. A. “opimus” [Hall, Reference Hall, Hall and Whitney1858a]; Anthracospirifer newberryi Sutherland and Harlow, Reference Sutherland and Harlow1973; Anthracospirifer sp., Alispirifer tamaulipensis Sour-Tovar, Álvarez, and Martínez-Chacón, Reference Sour-Tovar, Álvarez and Martínez-Chacón2005; Alispirifer transversus [Maxwell, Reference Maxwell1964]), and Spiriferinida (Spiriferellina campestris [White, Reference White1874]).

It is worth noting that the genera Weberproductus, Nuanducosia, and Martinezchaconia, as well as the species N. (N.) mixteco, W. donajiae, I. coodzavuii, D. transversum, B. inexpletucosta, F. magna, E. zapoteco, C. nunduva, N. sulcata, M. luisae, O. mixteca, L. perrilliatae n. sp., A. scientiana n. sp., A. oaxacaensis n. sp., N. pantojai, N. amplia, and S. mazateca were first described from specimens collected in the Ixtaltepec Formation (Sour-Tovar and Quiroz-Barroso, Reference Sour-Tovar and Quiroz-Barroso1989; Sour-Tovar and Martínez-Chacón, Reference Sour-Tovar and Martínez-Chacón2004; Torres-Martínez et al., Reference Torres-Martínez, Sour-Tovar and Pérez-Huerta2008; Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2012, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2016a, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2018).

Materials and methods

The material consists of 85 type specimens belonging to 15 species. Brachiopods are preserved as internal and external molds of both valves, and some samples are permineralized. In many cases, the internal regions of ventral valves are preserved as composite molds where it is possible to see some of the external morphology. All taxa were recollected in different fossiliferous intervals of the Ixtaltepec Formation, particularly from the API-1 to API-3 and API-5 to API-8. The most-representative samples were photographed and illustrated. Supraspecific morphological features were studied employing the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, specifically those chapters of the orders Rhynchonellida (Savage et al., Reference Savage, Manceñido, Owen, Carlson, Grant, Dagys, Dong-Li and Kaesler2002), Athyridida (Alvarez and Rong, Reference Alvarez, Rong and Kaesler2002), Spiriferida (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Johnson, Gourvennec, Hou and Kaesler2006), and Spiriferinida (Carter and Johnson, Reference Carter, Johnson and Kaesler2006). Likewise, we took into consideration the information recorded online in Fossilworks (http://fossilworks.org) and the Paleobiology Database (https://paleobiodb.org).

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

Types, figures, and other specimens examined in this study are deposited at Museo de Paleontología (MP) of the Facultad de Ciencias (FC), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Mexico City, Mexico. Type and figured specimens are designated in the descriptions by the prefix FCMP (Facultad de Ciencias Museo de Paleontología).

Systematic paleontology

Order Rhynchonellida Kuhn, Reference Kuhn1949

Superfamily Pugnacoidea Rzhonsnitskaia, Reference Rzhonsnitskaia and Thalmann1956

Family Petasmariidae Savage, Reference Savage, Cooper and Jin1996

Genus Leiorhynchoidea Cloud, Reference Cloud, King, Dunbar, Cloud and Miller1944

Type species

Leiorhynchoidea schucherti Cloud, Reference Cloud, King, Dunbar, Cloud and Miller1944, by original designation; Wordian (Coahuila, Mexico).

Leiorhynchoidea perrilliatae new species

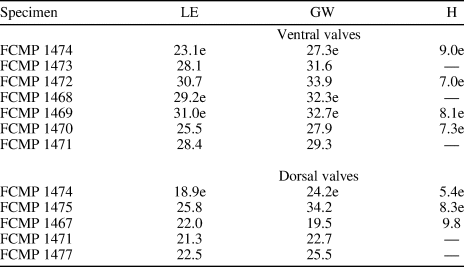

Figure 3.1–3.10

Holotype

One composed mold of dorsal valve (FCMP 1467).

Figure 3. (1–10) Leiorhynchoidea perrilliatae n. sp. (1, 2) Holotype, internal mold of dorsal valve and close-up of the posterior region, FCMP 1467; (3, 4) holotype, rubber cast and close-up of the posterior region, FCMP 1467; (5) paratype, internal mold of ventral valve, FCMP 1472; (6–8) paratypes, internal molds of dorsal valves, FCMP 1475, 1476, 1474, respectively; (9, 10) paratype, internal mold of ventral valve and close-up of the posterior region, FCMP 1478. (11, 12) Leiorhynchoidea sp., internal and external mold of dorsal valve, FCMP 1479. (13–23) Allorhynchus scientiana n. sp. (13) Holotype, internal mold in posterior view of articulated specimen, FCMP 1480; (14, 15) paratype, internal mold and rubber cast in lateral view of articulated specimen, FCMP 1481; (16) holotype, close-up of the posterior region of ventral valve, FCMP 1480; (17) rubber cast of holotype FCMP 1480; (18, 19) paratype, internal and external molds of dorsal valve, showing part of the opposite valve, FCMP 1485; (20) paratype, close-up of the posterior region, FCMP 1485; (21) paratype, external mold of dorsal valve, showing the posterior region of the ventral valve; also an articulated specimen in posterior view is observed, FCMP 1488; (22) paratype, external mold of dorsal valve with posterior region of the ventral valve, FCMP 1489; (23) external mold of dorsal valve, FCMP 1490. (24–29) Composita ovata Mather, Reference Mather1915. (24) Internal mold of ventral valve, FCMP 1492; (25–29) internal molds of dorsal valves, FCMP 1496, 1494, 1497, 1495, 1493, respectively. (30–35) Hustedia rotunda Lane, Reference Lane1962. (30, 31) Internal mold and rubber cast of ventral valve, FCMP 1498; (32) internal mold of dorsal valve, FCMP 1502; (33) rubber cast of ventral valve FCMP 1499; (34) internal mold of ventral valve, FCMP 1500; (35) rubber cast of dorsal valve FCMP 1501. Scale bars = 1 cm, except (2, 16, 20) = 0.5 cm.

Paratypes

Eight internal molds of ventral valves (FCMP 1468–1474, 1478), and five composed molds of dorsal valves, with external and internal traits (FCMP 1471, 1474–1477). In addition to this material, >70 specimens represent both valves in the collection.

Diagnosis

Medium to large shell, subcircular, with the greatest width at total mid-length; commissure broadly uniplicate; ventral valve slightly rounded in lateral profile, beak protrudes 4–5 mm beyond the hinge, with ~85° apical angle; shallow sulcus, originated posterior to total mid-length, with five costae, beginning ~7 mm anterior to beak; concentric lamellae more obvious on the anterior region; dorsal fold originated at mid-length, with 4–5 costae; dorsal median septum moderately long, extended slightly posterior to the mid-length; septalium short; crural bases thin, short, close to each other; dental sockets long and deep.

Occurrence

Interval API-7, Ixtaltepec Formation, Arroyo las Pulgas. Moscovian (Middle Pennsylvanian).

Description

Medium to large shell, subcircular, with the greatest width at total mid-length; posterior margins gently convex; commissure broadly uniplicate. Ventral valve slightly rounded in lateral profile, with the greatest convexity in the umbonal region; short and acute beak protrudes 4–5 mm beyond the hinge, with ~85° apical angle; delthyrium open apically; flanks laterally flattened; broad and shallow sulcus, originated posterior to total mid-length; ornamentation consists of five costae on sulcus, beginning ~7 mm anterior to beak; tongue low, serrate; concentric lamellae more obvious on the anterior region. Interior with ventral muscle field in a triangular shape, anteriorly elongate. Dorsal valve slightly convex with the greatest convexity in the umbonal region; umbonal region swollen and smooth; lateral flanks of the valve are gently convex; fold convex and elevated, originated at mid-length; ornamented by 4–5 costae and conspicuous lamellae on the entire valve. Interior with median septum moderately long, extended about posterior to the mid-length of the valve, becoming narrow towards the anterior region; septalium short; dorsal muscle field narrow; crural bases thin, short, close to each other; dental sockets long and deep. Measurements shown in Table 1.

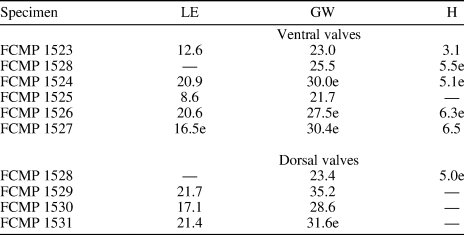

Table 1. Measurements of Leiorhynchoidea perrilliatae n. sp. LE, length; GW, greatest width; H, height; units, millimeters; e, estimated, sample incomplete.

Etymology

Named in honor of María del Carmen Perrilliat, a distinguished Mexican paleontologist dedicated to invertebrate paleontology.

Remarks

Leiorhynchoidea carbonífera (Girty, Reference Girty1911) from the Arco Hills Formation of the Visean–Serpukhovian of Idaho, USA (Butts, Reference Butts2007) is different from the species described in its smaller size, weaker costae on flanks, and in its umbonal apical angle of ~90°. Leiorhynchoidea rockymontana (Marcou, Reference Marcou1858) from the Tiawah Limestone of the Moscovian of Missouri, USA (Hoare, Reference Hoare1961) differs from L. perrilliatae n. sp. in its smaller subtriangular external shape, and the presence of 2–3 costae on the sulcus, as well as 3–4 costae on the fold. Leiorhynchoidea cloudi (Cooper in Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Dunbar, Duncan, Miller and Knight1953) from the upper levels of the Monos Formation (Capitanian) of Sonora, Mexico (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Dunbar, Duncan, Miller and Knight1953; Lara-Peña et al., Reference Lara-Peña, Navas-Parejo and Torres-Martínez2021) is characterized by its two broad costae on the sulcus and three on the fold, 4–5 weak costae on flanks, and crural bases enveloped by thickening of the hinge plate. Leiorhynchoidea schucherti from the Las Delicias Formation of the Wordian–Capitanian of Coahuila, Mexico (Cloud, Reference Cloud, King, Dunbar, Cloud and Miller1944) is different from the new species by its subtriangular shape, ventral sulcus originating slightly anterior to the mid-length, the occurrence of 2–6 rounded costae on the sulcus, 3–7 costae on the fold, and the septum extended beyond total mid-length. The Santiago Ixtaltepec specimens also were compared with Leiorhynchoidea carbonífera from the Heath Formation of the Mississippian of Montana, USA, described by Easton (Reference Easton1962), whose assignation was questioned by Butts (Reference Butts2007). This taxon is distinguished from the Oaxacan species by its more numerous costae on sulcus and fold, apical angle of the umbo 130–140°, and the presence of a septum that reaches two-thirds of the total length.

Leiorhynchoidea sp.

Figure 3.11, 3.12

Occurrence

Interval API-3, Ixtaltepec Formation, Arroyo las Pulgas; Serpukhovian (Upper Mississippian).

Description

Medium-size valve, subtriangular in outline, greatest width at mid-length, measuring 25 mm in width; fold low, originated to the mid-length; ornamentation consists of three broad and rounded costae; numerous and narrow concentric lamellae cover the entire valve.

Materials

Internal and external mold of dorsal valve (FCMP 1479).

Remarks

The material is different from Leiorhynchoidea perrilliatae n. sp. of the level API-7 by the subtriangular outline, arrangement of lamellae, and the fewer number of rounded costae on the dorsal fold. Our specimen is dissimilar to other taxa previously described; however, the lack of material and poor preservation prevents us from a specific assignment.

Superfamily Wellerelloidea Licharew, Reference Licharew, Kiparisova, Markowskii and Radchencko1956

Family Allorhynchidae Cooper and Grant, Reference Cooper and Grant1976

Genus Allorhynchus Weller, Reference Weller1910

Type species

Rhynchonella heteropsis Winchell, Reference Winchell1865, by subsequent designation of Weller (Reference Weller1910); Tournaisian (Michigan, USA).

Allorhynchus scientiana new species

Figure 3.13–3.23

Holotype

An internal mold of articulated specimen (FCMP 1480).

Diagnosis

Subpentagonal outline, with the greatest width anterior to mid-length, anterior commissure uniplicate, and denticulate; ventral valve convex, mainly at the anterior region; beak curved dorsally with 43–56° angle; delthyrium open, triangular, deltidial plates narrow; sulcus initiating about one-third anterior to beak, forming a low tongue at the anterior region; flanks slightly convex; ornamented by simple and subangular costae, with four costae on the sulcus and eight costae on each flank of the valve; with two postero-cardinal costae not very noticeable; interior with ventral muscle field anteriorly elongate; dorsal valve with fold broad, ornamented by five costae, with eight costae on each flank of the valve; interior with posterior adductors elongate and narrow.

Occurrence

Interval API-2, Ixtaltepec Formation, Arroyo las Pulgas; Serpukhovian (Upper Mississippian).

Description

Small, biconvex, and subpentagonal shell, with greatest width anterior to mid-length, anterior commissure uniplicate, and denticulate. Ventral valve convex, mainly at the anterior region; beak straight, short, slightly curved dorsally with 43–56° angle; delthyrium open, triangular, deltidial plates narrow; shallow sulcus, originating about one-third anterior to beak, narrow in the beginning, becoming slightly broad towards the anterior margin where it forms a low tongue; flanks faintly convex; ornamentation consists of complete, simple, and subangular costae; four costae ornament the sulcus, eight costae are on each flank of the valve; the two adjacent costae to postero-cardinal margins are very thin and not very noticeable; interior with ventral muscle field anteriorly elongate. Dorsal valve strongly convex at the anterior region; fold broad, corresponding to ventral sulcus; fold ornamented by five costae, with eight costae on each flank of the valve; the two last postero-cardinal costae are thinner than the rest. Interior with posterior adductors elongate and narrow; dorsal median septum absent. Measurements shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Measurements of Allorhynchus scientiana n. sp. LE, length; GW, greatest width; H, height; units, millimeters; e, estimated, sample incomplete.

Etymology

Named for the Faculty of Sciences, UNAM, trainer institution of numerous Mexican paleontologists.

Paratypes

An internal mold of articulated specimen in lateral view (FCMP 1481), three internal molds of ventral valve (FCMP 1482–1484), and six internal molds of dorsal valve, showing the posterior region of the ventral valve (FCMP 1482, 1485–1489), and an external mold of dorsal valve (FCMP 1490). In addition to this material, >90 specimens represent both valves in the collection.

Remarks

Allorhynchus heteropsis (Winchell, Reference Winchell1865) from the Tournaisian of Burlington, Iowa (Weller, Reference Weller1914) differs from A. scientiana n. sp. by its smaller size, different angle of the beak, sulcus originating to the middle of the total length, and fewer costae on each flank of both valves. Allorhynchus macra (Hall, Reference Hall1858b) from the Visean of Salem Limestone, Indiana (Weller, Reference Weller1914) is different from the new species by its smaller size, less angular beak, angular costae, and concentric striae. Allorhynchus acutiplicatum Weller, Reference Weller1914, from the Serpukhovian of the Carterville Formation of Missouri (Weller, Reference Weller1914) is dissimilar from A. scientiana n. sp. by its smaller size, less angular beak, sulcus initiating on the corpus, and a greater number of not very noticeable postero-cardinal costae. Allorhynchus maior Martínez-Chacón in Martínez-Chacón and Delvolvé, Reference Martínez-Chacón and Delvolvé1986, from the Serpukhovian of the French Central Pyrenees (Martínez-Chacón and Delvolvé, Reference Martínez-Chacón and Delvolvé1986) is characterized by its greater size, external outline more transverse, sulcus originating at mid-length, and fewer costae on each flank. Allorhynchus intermedius Martínez-Chacón in Martínez-Chacón and Delvolvé, Reference Martínez-Chacón and Delvolvé1986, from the Serpukhovian–Bashkirian of the French Central Pyrenees (Martínez-Chacón and Delvolvé, Reference Martínez-Chacón and Delvolvé1986) is different from the Mexican species by its subtriangular and transverse outline, flanks flattened, and fewer costae on the sulcus and flanks. This is the first report of the genus in Mexico.

Order Athyridida Boucot, Johnson, and Staton, Reference Boucot, Johnson and Staton1964

Suborder Athyrididina Boucot, Johnson, and Staton, Reference Boucot, Johnson and Staton1964

Superfamily Athyridoidea Davidson, Reference Davidson1881

Family Athyrididae Davidson, Reference Davidson1881

Subfamily Spirigerellinae Grunt, Reference Grunt, Ruzhencev and Sarycheva1965

Genus Composita Brown, Reference Brown1849

Type species

Spirifer ambiguus Sowerby, Reference Sowerby1822, by subsequent designation of Brown (Reference Brown1849); Visean (Derbyshire, England).

Composita ovata Mather, Reference Mather1915

Figure 3.24–3.29

- Reference Mather1915

Composita ovata Mather, p. 202, pl. 14, figs. 6–6c.

- Reference Dunbar and Condra1932

Composita ovata; Dunbar and Condra, p. 370, pl. 43, figs. 14–19.

- Reference Hoare1961

Composita ovata; Hoare, p. 90, pl. 12, figs. 3, 4.

- Reference Sutherland and Harlow1973

Composita “ovata”; Sutherland and Harlow, p. 64, pl. 14, figs. 18–21.

- Reference Gordon1975

Composita ovata; Gordon, p. 63, pl. 10, figs. 1–15, 26–32.

Holotype

Articulated shell from the Morrow Group of Arkansas and Oklahoma, United States (Mather, Reference Mather1915, pl. 14, fig. 6).

Occurrence

Interval API-7, Ixtaltepec Formation, Arroyo las Pulgas; Moscovian (Middle Pennsylvanian).

Description

Biconvex shell, outline subovate to subcircular, with the greatest width at mid-length; shells up to 25.6 mm in length and 24.5 mm in width; ventral valve with greatest convexity in the posterior region, shallow sulcus initiating near umbonal region; shell ornamented by sublamellar growth lines and fine radial striae; interior with narrow diductor scars; dorsal valve with a low fold that, along with the sulcus, forms a deflection in the commissure, and a dorsal interior with a moderately long myophragm; adductor scars extended and narrow; triangular inner hinge plate.

Materials

Two internal molds of ventral valves (FCMP 1491, 1492), and five internal molds of dorsal valves (FCMP 1493–1497).

Remarks

This species has been widely reported in the Pennsylvanian of the United States, with records in Nebraska, Kansas (Dunbar and Condra, Reference Dunbar and Condra1932), New Mexico (Gehrig, Reference Gehrig1958), Missouri (Hoare, Reference Hoare1961), Montana (Easton, Reference Easton1962), Nevada (Lane, Reference Lane1963), Ohio (Sturgeon and Hoare, Reference Sturgeon and Hoare1968), Wyoming (Gordon, Reference Gordon1975), and Colorado (Henry, Reference Henry1998). In addition to this material, >50 specimens represent both valves in the collection.

Suborder Retziidina Boucot, Johnson, and Staton, Reference Boucot, Johnson and Staton1964

Superfamily Retzioidea Waagen, Reference Waagen1883

Family Neoretziidae Dagys, Reference Dagys1972

Subfamily Hustediinae Grunt, Reference Grunt1986

Genus Hustedia Hall and Clarke, Reference Hall and Clarke1893

Type species

Terebratula mormoni Marcou, Reference Marcou1858, by subsequent designation of Beede (Reference Beede1900); upper Carboniferous (Nebraska, USA).

Hustedia rotunda Lane, Reference Lane1962

Figure 3.30–3.35

- Reference Lane1962

Hustedia rotunda Lane, p. 905, pl. 128, figs. 1, 2.

Holotype

Articulated shell, showing interior spire, from Cottonwood Creek, Nevada, United States (Lane, Reference Lane1962, pl. 128, fig. 1).

Occurrence

Interval API-7, Ixtaltepec Formation, Arroyo las Pulgas; Moscovian (Middle Pennsylvanian).

Description

Small, biconvex, and subovate shells, with commissure rectimarginate; shells up to 12.8 mm in length and 10.8 mm in width; ventral valve with greatest convexity in the posterior region, weak sulcus; both valves ornamented with 22–25 simple and rounded costae, with depressions of the same width as the costae, central costae slightly greater; dorsal valve subcircular, and dorsal fold absent.

Materials

Three internal molds of ventral valves (FCMP 1498–1500) and two internal molds of dorsal valves (FCMP 1501, 1502).

Remarks

The features of the specimens coincide with those referred to Hustedia rotunda from the Moscovian of the Ely Group, Nevada, United States (Lane, Reference Lane1962). Hustedia mormoni (Marcou, Reference Marcou1858) from the La Joya Formation of the Carboniferous of Sierra Agua Verde, Sonora, Mexico (Jiménez-López et al., Reference Jiménez-López, Sour-Tovar, Buitrón-Sánchez and Palafox-Reyes2018) is dissimilar to H. rotunda in its subpentagonal shape in outline, smaller size, 10–13 simple broader costae, and narrower intercostae depressions. In addition to this material, >40 specimens represent both valves in the collection.

Order Spiriferida Waagen, Reference Waagen1883

Suborder Spiriferidina Waagen, Reference Waagen1883

Superfamily Ambocoelioidea George, Reference George1931

Family Ambocoeliidae George, Reference George1931

Subfamily Ambocoeliinae George, Reference George1931

Genus Crurithyris George, Reference George1931

Type species

Spirifer urei Fleming, Reference Fleming1828, by subsequent designation of Beede (Reference Beede1900); Visean (Lanarkshire, Scotland).

Crurithyris expansa (Dunbar and Condra, Reference Dunbar and Condra1932)

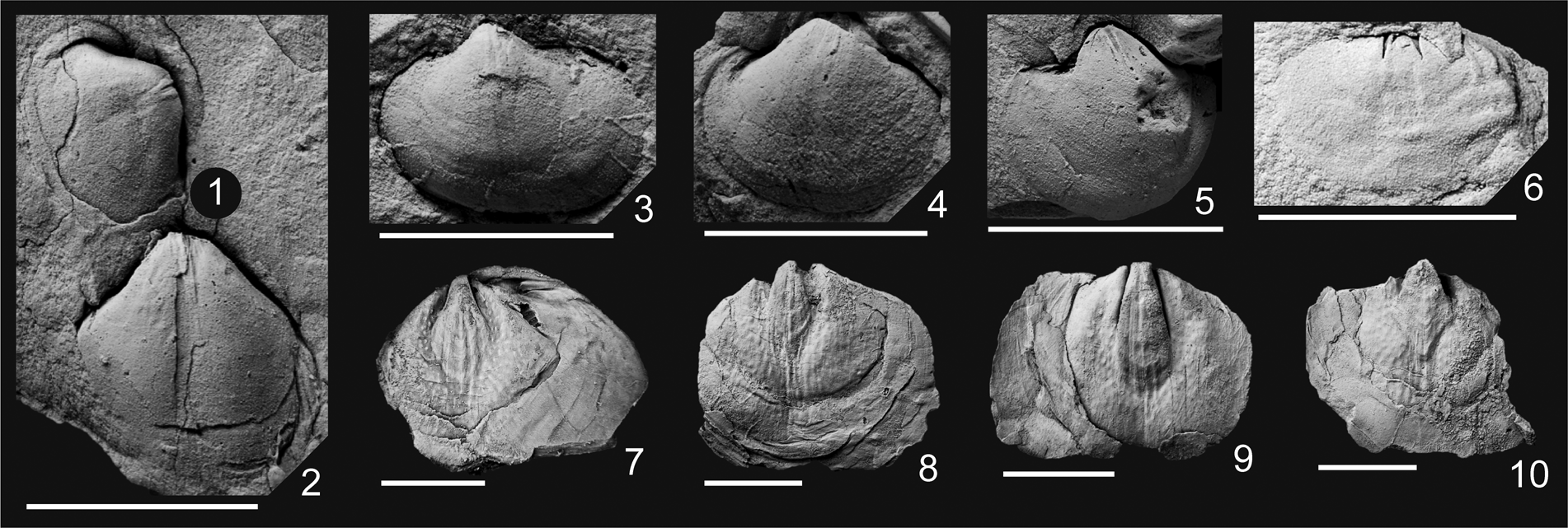

Figure 4.1–4.6

- Reference Dunbar and Condra1932

Ambocoelia expansa Dunbar and Condra, p. 348, pl. 42, figs. 15–17.

- Reference Mudge and Yochelson1962

Crurithyris expansa; Mudge and Yochelson, p. 77, pl. 13, figs. 2, 3.

- Reference Olszewski and Patzkowsky2001

Crurithyris expansa; Olszewski and Patzkowsky, p. 665.

Figure 4. (1–6) Crurithyris expansa (Dunbar and Condra, Reference Dunbar and Condra1932). (1–5) Internal molds of ventral valves, FCMP 1503, 1504, 1505, 1506, 1507, respectively; (6) internal mold of dorsal valve, FCMP 1508. (7–10) Martiniid gen. and sp. indeterminate. (7, 8) Internal molds of articulated specimens in ventral view, FCMP 1509, 1510, respectively; (9) internal mold of ventral valve FCMP 1511; (10) internal mold of dorsal valve, FCMP 1512. Scale bars = 1 cm.

Holotype

Articulated shell from Hughes Creek Shale, Nebraska (Dunbar and Condra, Reference Dunbar and Condra1932, pl. 42, figs. 15, 16).

Occurrence

Interval API-7, Ixtaltepec Formation, Arroyo las Pulgas; Moscovian (Middle Pennsylvanian).

Description

Large-sized shell for the genus, ventribiconvex shape, and subovate outline; with greatest width at mid-length, shells up to 11.2 mm in length and 12.4 mm in width; ventral valve gibbous in the umbonal region, beak strongly curved; narrow and shallow sulcus; cardinal extremities rounded; dorsal valve with a weak sulcus; ornamentation of both valves is composed of fine growth lines.

Materials

Five internal molds of ventral valves (FCMP 1503–1507) and an internal mold of a dorsal valve (FCMP 1508).

Remarks

The morphological traits allowed us to relate the Oaxacan specimens with Crurithyris expansa from the Moscovian of Nebraska (Dunbar and Condra, Reference Dunbar and Condra1932, p. 348, 349). This species is clearly distinguished from others of the genus by its greater size, transverse shape, smaller umbo, and beak strongly curved (Dunbar and Condra, Reference Dunbar and Condra1932). The Ixtaltepec Formation specimens display a slightly greater size than those described in the Pennsylvanian of Nebraska. In addition to this material, >20 specimens represent both valves in the collection.

Superfamily Martinioidea Waagen, Reference Waagen1883

Family Martiniidae Waagen, Reference Waagen1883

Martiniid gen. and sp. Indeterminate

Figure 4.7–4.10

Occurrence

Interval API-2, Ixtaltepec Formation, Arroyo las Pulgas; Serpukhovian (Upper Mississippian).

Description

Medium-sized shell, subpentagonal in outline; large shells up to 26.9 mm in length and 29.4 mm in width; inconspicuous cardinal extremities; commissure uniplicate; ventral valve convex; broad and shallow sulcus, originating at the umbo; short interarea, apsacline; dorsal valve with slightly high fold; ornamentation of both valves composed of indistinct growth lines and concentric plications.

Materials

Two internal molds of articulated specimens (FCMP 1509, 1510), an internal mold of a ventral valve (FCMP 1511), and an internal mold of a dorsal valve (FCMP 1512).

Remarks

The morphological features allowed us to relate these specimens with taxa belonging to the Family Martiniidae (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Johnson, Gourvennec, Hou and Kaesler2006, p. H1748–H1757); however, the preservation did not allow us to make a reliable generic assignment.

Superfamily Spiriferoidea King, Reference King1846

Family Spiriferidae King, Reference King1846

Subfamily Sergospiriferinae Carter in Carter et al., Reference Carter, Johnson, Gourvennec and Hou1994

Genus Anthracospirifer Lane, Reference Lane1963

Type species

Anthracospirifer birdspringensis Lane, Reference Lane1963, by original designation; Bashkirian (Nevada, USA).

Anthracospirifer occiduus (Sadlick, Reference Sadlick1960)

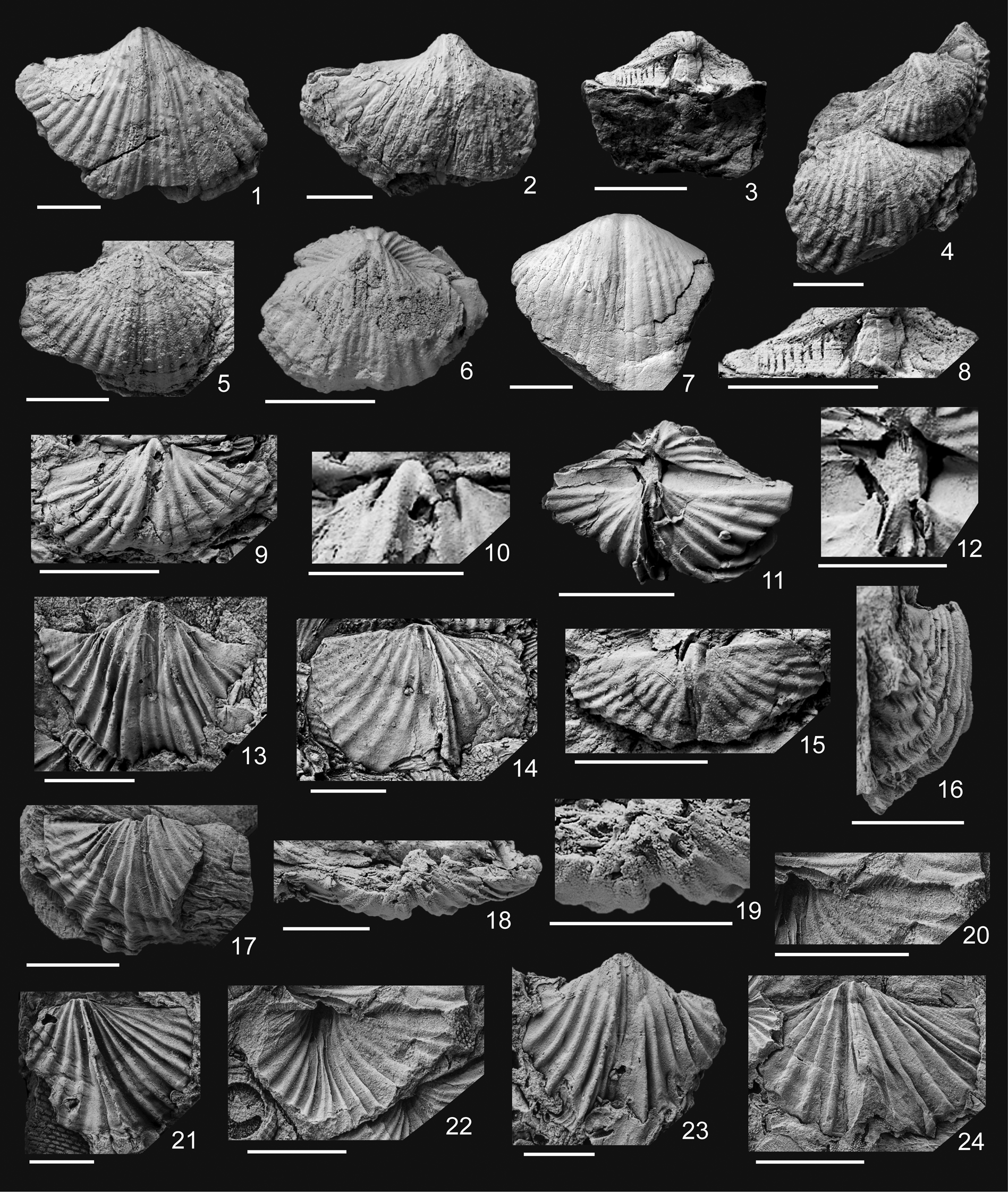

Figure 5.1–5.8

- Reference Girty1927

Spirifer opimus var. occidentalis Girty, pl. 27, figs. 28–31.

- Reference Sadlick1960

Spirifer occiduus Sadlick, p. 1210.

- Reference Hoare1961

Spirifer occiduus; Hoare, p. 73, pl. 9, figs. 8–10.

- Reference Lane1962

Spirifer occiduus; Lane, p. 888, pl. 128, figs. 3–7.

- Reference Lane1963

Anthracospirifer occiduus; Lane, p. 387.

- Reference Lane1964

Anthracospirifer occiduus; Lane, p. 783.

- Reference Sturgeon and Hoare1968

Anthracospirifer occiduus; Sturgeon and Hoare, p. 62, pl. 20, figs. 1–7.

- Reference Sutherland and Harlow1973

Anthracospirifer “occiduus”; Sutherland and Harlow, p. 85, pl. 16, fig. 20.

- Reference Gordon1975

Anthracospirifer occiduus; Gordon, p. 67, pl. 11, figs. 24–32.

- Reference Carter and Poletaev1998

Anthracospirifer occiduus; Carter and Poletaev, p. 160, figs. 24.9–24.13.

- Reference Butts2007

Anthracospirifer cf. occiduus; Butts, p. 58, figs. 5.34–5.36.

- Reference Jiménez-López, Sour-Tovar, Buitrón-Sánchez and Palafox-Reyes2018

Anthracospirifer occiduus; Jiménez-López et al., p. 641, figs. 3g, h.

Figure 5. (1–8) Anthracospirifer occiduus (Sadlick, Reference Sadlick1960). (1, 2) Ventral valves, FCMP 1514, 1515, respectively; (3) ventral valve in dorsal view, FCMP 1516; (4) two ventral valves in the same sample, FCMP 1517, 1518; (5) ventral valve, FCMP 1519; (6) articulated sample in ventral view, FCMP 1513; (7) ventral valve, FCMP 1520; (8) close-up of the posterior region of ventral valve, FCMP 1516. (9–24) Anthracospirifer oaxacaensis n. sp. (9, 10) Paratype, internal mold of ventral valve and close-up of the posterior region, FCMP 1523; (11, 12) holotype, internal mold of articulated specimen in posterior view and close-up of the central region, FCMP 1522; (13) paratype, internal mold of ventral valve, FCMP 1525; (14) paratype internal mold of dorsal valve, FCMP 1529; (15) paratype, internal mold of ventral valve, FCMP 1524; (16, 17) paratype, internal mold of ventral valve in lateral and ventral views, FCMP 1527; (18, 19) paratype, internal mold of ventral valve in posterior view with close-up, FCMP 1526; (20) paratype, close-up of the interarea of the external mold of ventral valve, showing the parallel striae, FCMP 1527; (21) paratype, internal mold of dorsal valve, FCMP 1531; (22) paratype, external mold of ventral valve, FCMP 1527; (23) paratype, internal mold of ventral valve, FCMP 1526; (24) paratype, internal mold of dorsal valve, FCMP 1530. Scale bars = 1 cm, except (10, 12) = 0.5 cm.

Holotype

Crushed shell that retains both valves. Sample from the Wells Formation, Crow Creek quadrangle, Idaho, United States (Girty, Reference Girty1927, pl. 27, figs. 28, 29).

Occurrence

Intervals API-1, API-2, API-5, and API-6, Ixtaltepec Formation, Arroyo las Pulgas. Serpukhovian–Bashkirian (Upper Mississippian–Lower Pennsylvanian).

Description

Small- or medium-sized biconvex shell, subrectangular in outline, moderately transverse, with the greatest width at the hinge-line; large shells up to 28.3 mm in length and 43.2 mm in width; cardinal extremities with 85–90° angle; commissure uniplicate; ventral valve with beak short, dorsally curved; delthyrium subtriangular; interarea slightly concave, apsacline, ~4 mm in the largest specimen, with parallel striae; shallow sulcus, initiating at the beak, with linguliform shape at the commissure; sulcus ornamented by one simple central costa, followed by two costae on each side originating from the delimitating costae of the sulcus, which in turn are bifurcated once to the outside; 11 simple and rounded costae on each lateral flank, with fine concentric lirae on the entire shell; dorsal valve with fold originating in the umbonal region, displaying four costae derived from two costae bifurcated once, as well as 10 costae on each lateral flank, those nearest to the fold are bifurcated but the rest are simple.

Materials

An articulated shell (FCMP 1513), seven ventral valves (FCMP 1514–1520), and a dorsal valve (FCMP 1521).

Remarks

Although the species had already been recorded in the initial works of the Ixtaltepec Formation, this is the first formal study where the taxon is described and corroborated. In addition to this material, >40 specimens represent both valves in the collection.

Anthracospirifer oaxacaensis new species

Figure 5.9–5.24

Holotype

An internal mold of an articulated specimen (FCMP 1522).

Paratypes

Six internal molds of ventral valves (FCMP 1523–1528), and four internal molds of dorsal valves (FCMP 1528–1531). In addition to this material, >15 specimens represent both valves in the collection.

Diagnosis

Medium-sized and subpentagonal shell, more transverse in juvenile specimens, with the greatest width at the hinge-line; cardinal extremities with ~70–75° angle; ventral interarea slightly denticulate at margin, faintly concave, apsacline, with parallel and slightly diagonal striae; sulcus moderately deep, with a costellation resembling A. occiduus; 7–8 subrounded costae on each lateral flank, the two costae nearest the sulcus are bifurcated once; fine concentric and successive lirae cover the entire shell, and some juvenile specimens display anterior concentric lamellae; sulcus linguliform initiating at the beak, curved dorsally; delthyrium subtriangular; well-developed ventral adminicula; dorsal interarea narrow; fold with two bifurcate costae; lateral flanks with seven costae, the two costae nearest the fold are derived from a bifurcation.

Occurrence

Intervals API-7 and API-8, Ixtaltepec Formation, Arroyo las Pulgas; Moscovian (Middle Pennsylvanian).

Description

Medium-sized and subpentagonal shell, more transverse in juvenile specimens, with greatest width at the hinge-line; cardinal extremities with ~70–75° angle; commissure uniplicate; ventral valve convex, more gibbous in the posterior region; interarea slightly denticulate at margin, faintly concave, apsacline, 4 mm in height in the largest specimen, with parallel and slightly diagonal striae; sulcus moderately deep, with a costellation resembling A. occiduus; each lateral flank displays 7–8 subrounded costae, the four costae nearest the sulcus originate from two bifurcated costae, the others are simple; interspaces are slightly narrower than the costae; fine concentric and successive lirae cover the entire shell, although some juvenile specimens display anterior concentric lamellae; sulcus linguliform initiating at the beak, which is short and curved dorsally; delthyrium subtriangular; dental adminicula well developed but moderate; slightly divergent dental flanges; diductor scars narrow. Dorsal valve convex; interarea narrow; fold beginning in the umbonal region, with four costae originating from two bifurcate costae; lateral flanks with seven costae, the two costae nearest the fold are derived from a bifurcation, the rest are simple. Measurements shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Measurements of Anthracospirifer oaxacaensis n. sp. LE, length; GW, greatest width; H, height; units, millimeters; e, estimated, sample incomplete.

Etymology

Referring to Oaxaca state, Mexico.

Remarks

Anthracospirifer opimus from the Moscovian of the Cherokee Shale of Nebraska (Dunbar and Condra, Reference Dunbar and Condra1932) is different from the new species by its subtriangular outline, strongly convex shell, rounded cardinal extremities, shallow sulcus, and arrangement of costellation. Anthracospirifer rockymontanus from the Moscovian of the Tiawah Formation, Seville Limestone, and Burgner Formation of Missouri (Hoare, Reference Hoare1961) is dissimilar to A. oaxacaensis n. sp. in its smaller size, greatest width near the hinge-line, arched beak, rounded cardinal extremities, and more numerous costae on the fold. Anthracospirifer birdspringensis from the Bashkirian of the Bird Spring Formation of Nevada (Lane, Reference Lane1963) is different from A. oaxacaensis n. sp. by its more transverse outline, a greater number and distinct arrangement of costae, and shallower sulcus. The specimens of A. oaxacaensis n. sp. resemble Anthracospirifer occiduus from Santiago Ixtaltepec, Oaxaca; however, the new species differs in its subpentagonal shape, more acute cardinal extremities, deeper sulcus, striae from the interarea slightly diagonal, and different costellation arrangement on the lateral flanks.

Anthracospirifer cf. A. “opimus” (Hall, Reference Hall, Hall and Whitney1858a)

Figure 6.1, 6.2

- Reference Hall, Hall and Whitney1858a

Spirifer opimus Hall, p. 711, pl. 28, fig. 1a, b.

- Reference Girty1903

Spirifer opimus; Girty, p. 46.

- Reference Dunbar and Condra1932

Spirifer opimus; Dunbar and Condra, p. 320, pl. 41, figs. 10–11c.

- Reference Hoare1961

Spirifer opimus; Hoare, p. 70, pl. 9, figs. 1–3.

- Reference Lane1963

Anthracospirifer opimus; Lane, p. 387.

- Reference Lane1964

Anthracospirifer opimus; Lane, p. 781.

- Reference Spencer1967

Spirifer opimus; Spencer, p. 16, figs. 1, 9, 11.

- Reference Sturgeon and Hoare1968

Anthracospirifer opimus; Sturgeon and Hoare, p. 62, pl. 19, figs. 30–32.

- Reference Sutherland and Harlow1973

Anthracospirifer “opimus”; Sutherland and Harlow, p. 85, pl. 16, figs. 17–19.

Figure 6. (1, 2) Anthracospirifer cf. A. “opimus” (Hall, Reference Hall, Hall and Whitney1858a), ventral valve in ventral and lateral views, FCMP 1532. (3–6) Anthracospirifer newberryi Sutherland and Harlow, Reference Sutherland and Harlow1973; (3) internal mold of ventral valve, FCMP 1533; (4) internal mold of dorsal valve, FCMP 1534; (5) close-up of the posterior region of ventral valve; FCMP 1533; (6) internal mold of dorsal valve, FCMP 1535. (7) Anthracospirifer sp., internal mold of ventral valve, FCMP 1536. (8–17) Alispirifer tamaulipensis Sour-Tovar, Álvarez, and Martínez-Chacón, Reference Sour-Tovar, Álvarez and Martínez-Chacón2005. (7) Internal mold of ventral valve, FCMP 1538; (9) external mold of ventral valve, FCMP 1542; (10) internal mold of ventral valve, FCMP 1540; (11) internal mold of dorsal valve, FCMP 1543; (12) internal molds of ventral valve, FCMP 1539; (13, 14) articulated internal mold in posterior view with close-up of central region, FCMP 1537; (15, 16) external molds of ventral valves, FCMP 1538, 1539; (17) internal mold of ventral valve, FCMP 1541. (18–23) Alispirifer transversus (Maxwell, Reference Maxwell1964). (18, 19) Ventral valve in ventral and posterior views, FCMP 1545; (20, 21) internal and external molds of articulated specimen in posterior views, FCMP 1544; (22) close-up of the posterior region of specimen FCMP 1544; (23) ventral valve, FCMP 1546. (24–26) Spiriferellina campestris (White, Reference White1874). (24, 25) Internal molds of ventral valves, FCMP 1549, 1548, respectively; (26) internal mold of dorsal valve, FCMP 1551. Scale bars = 1 cm, except (5, 14, 22) = 0.5 cm.

Holotype

Articulated specimen from the Coal measures of Ohio, United States (Hall, Reference Hall, Hall and Whitney1858a, pl. 28, fig. 1).

Occurrence

Interval API-5, Ixtaltepec Formation, Arroyo las Pulgas; Bashkirian (Lower Pennsylvanian).

Description

Medium-sized and strongly convex valve, subtriangular in outline, with the greatest width anterior to hinge-line; measuring ~20.5 mm in length and 26.6 in width; beak and umbo strongly arched, cardinal extremities rounded; interarea apsacline; shallow sulcus originating at the beak, with a simple central costa followed on each side by one costa derived from the bifurcation of the costae that delimit the sulcus, as well as nine simple, rounded, and broad costae on each lateral flank, with very narrow interspaces.

Materials

A fragmented ventral valve (FCMP 1532).

Remarks

The morphological traits allow correlating the sample with A. opimus from the Moscovian of the Cherokee Shale of Nebraska (Dunbar and Condra, Reference Dunbar and Condra1932, p. 320–322, pl. 41, figs. 10–11c), the Putnam Hill Formation of Ohio (Sturgeon and Hoare, Reference Sturgeon and Hoare1968, p. 62, pl. 19, figs. 9, 30–32), and the La Pasada Formation of New Mexico (Sutherland and Harlow, Reference Sutherland and Harlow1973, p. 85, 86, pl. 16, figs. 17–19). Despite these features, it was not possible to make a complete specific assignment due to the preservation of the specimen. The species is considered in a typological sense because the study locality and stratigraphic horizon of Hall (Reference Hall, Hall and Whitney1858a) are unknown (Sutherland and Harlow, Reference Sutherland and Harlow1973).

Anthracospirifer newberryi Sutherland and Harlow, Reference Sutherland and Harlow1973

Figure 6.3–6.6

- Reference Sutherland and Harlow1973

Anthracospirifer newberryi Sutherland and Harlow, p. 78, pl. 16, figs. 1–4.

- Reference Gordon and McKee1982

Anthracospirifer newberryi; Gordon, p. 118, pl. F3, figs. 20, 21.

Holotype

An articulated specimen from the Morrow Series, New Mexico, United States (Sutherland and Harlow, Reference Sutherland and Harlow1973, pl. 16, fig. 1).

Occurrence

Interval API-6, Ixtaltepec Formation, Arroyo las Pulgas; upper Bashkirian (Lower Pennsylvanian).

Description

Small- or medium-sized, biconvex and very transverse shells, with cardinal extremities alate; commissure uniplicate; ventral valve convex, 11.9 mm in length and 26.4 mm in width; interarea low and orthocline, with striae; sulcus shallow and obscure, originating 2 mm from beak and becoming inconspicuous anteriorly, ornamented by a central simple costa followed on each margin of the sulcus by one bifurcated costa; 13 low costae ornament each lateral flank, broader anteriorly; the intercostal grooves are subangular; fine, and transverse lirae on the entire shell; interior with dental adminicula short and diductor scars narrow; dorsal valve more convex than the opposite valve; fold low, well delimited by a pair bifurcated costae to the center; 10 similar costae on the opposite valve on each lateral flank; microornamentation capillate, with slightly lamellose growth lines.

Materials

An internal mold of a ventral valve (FCMP 1533) and two internal molds of dorsal valves (FCMP 1534, 1535).

Remarks

Anthracospirifer newberryi is distinguishable from the other Oaxacan species of the genus by the shape of sulcus and fold, the orthocline ventral interarea, and arrangement and number of costae.

Anthracospirifer sp.

Figure 6.7

Occurrence

Interval API-7, Ixtaltepec Formation, Arroyo las Pulgas; Moscovian (Middle Pennsylvanian).

Description

Small, convex, and subpentagonal valve, ~19.5 mm in length and 19 mm in width; interarea apsacline; beak minute and strongly curved, cardinal extremities rounded; shallow sulcus initiating at the beak; sulcus with a simple central costa, followed on each side by one costa derived from the bifurcation of the delimiting costae of the sulcus, which are broader, with six simple and rounded costae on each lateral flank, becoming slender towards the anterior region; intercostal grooves strongly narrow.

Materials

Internal mold of a ventral valve (FCMP 1536)

Remarks

Although the Oaxacan specimen resembles Anthracospirifer rockymontanus from the Moscovian of the Putnam Hill Limestone, Ohio (Sturgeon and Hoare, Reference Sturgeon and Hoare1968, p. 61, pl. 19, fig. 26), and Anthracospirifer welleri welleri (Branson and Greger, Reference Branson and Greger1918) from the Serpukhovian–Bashkirian of the Amsden Formation, Wyoming (Gordon, Reference Gordon1975, p. 72, pl. 12, figs. 6, 12), our specimen can be distinguished by its smaller beak and different number, arrangement, and shape of the costae. The preservation, deformation, and lack of other specimens did not allow a specific assignment.

Superfamily Paeckelmanelloidea Ivanova, Reference Ivanova1972

Family Strophopleuridae Carter, Reference Carter1974

Subfamily Pterospiriferinae Waterhouse, Reference Waterhouse1975

Genus Alispirifer Campbell, Reference Campbell1961

Type species

Alispirifer laminosus Campbell, Reference Campbell1961, by original designation; Visean (New South Wales, Australia).

Alispirifer tamaulipensis Sour-Tovar, Álvarez, and Martínez-Chacón, Reference Sour-Tovar, Álvarez and Martínez-Chacón2005

Figure 6.8–6.17

Reference Sour-Tovar, Álvarez and Martínez-Chacón2005 Alispirifer tamaulipensis Sour-Tovar, Álvarez, and Martínez-Chacón, p. 475, fig. 5.

Holotype

Internal and external molds of a ventral valve from the Middle Member of the Vicente Guerrero Formation, Cañón de la Peregrina, Tamaulipas, Mexico (Sour-Tovar et al., Reference Sour-Tovar, Álvarez and Martínez-Chacón2005, fig. 5).

Occurrence

Interval API-3, Ixtaltepec Formation, Arroyo las Pulgas; Serpukhovian (Upper Mississippian).

Description

Small- to medium-sized biconvex shell, transverse, with a length-width proportion of 1:2; cardinal extremities alate; commissure uniplicate; large shells up to 20.3 mm in length and 41.4 mm in width; ventral valve with narrow, smooth, and shallow well-delimited sulcus, initiating at the beak; low and rounded plications, 8–9 occupying each lateral flank; microornamentation of radial lirae, very close to each other, and a few concentric lamellae; interarea apsacline and denticulate, moderately high, 3 mm on average; delthyrium narrow, with apical callus; interior with rhomboidal muscle scars; dorsal valve with fold gently high; ornamentation similar to the opposite valve; interior with small cardinal process, well-developed socket plates, and shallow sockets.

Materials

An articulated internal mold (FCMP 1537), two internal and external molds of ventral valves (FCMP 1538, 1539), two internal molds of ventral valves (FCMP 1540, 1541), an external mold of a ventral valve (FCMP 1542), and an internal mold of a dorsal valve (FCMP 1543).

Remarks

The specimens display those typical traits of the species described by Sour-Tovar et al. (Reference Sour-Tovar, Álvarez and Martínez-Chacón2005) from the Tournaisian–Visean of the Vicente Guerrero Formation, Tamaulipas, Mexico. Alispirifer tamaulipensis described herein occurs at the interval API-3 from the Serpukhovian of the Ixtaltepec Formation, extending the stratigraphic range of the species to the Upper Mississippian. In addition to this material, >9 specimens represent both valves in the collection.

Alispirifer transversus (Maxwell, Reference Maxwell1964)

Figure 6.18–6.23

- Reference Maxwell1964

Alispirifer laminosus var. transversus Maxwell, p. 28, pl. 5, figs. 33–38.

- Reference Roberts, Hunt and Thompson1976

Alispirifer transversus; Roberts et al., p. 206.

- Reference Cisterna1997

Alispirifer transversus; Cisterna, p. 156, pl. 1, figs. 1–5, 7, 9.

- Reference Angiolini, Racheboeuf, Villarroel and Concha2003

Alispirifer cf. transversus; Angiolini et al., p. 156, figs. 2g, k, o.

- Reference Pastor-Chacón, Reyes-Abril, Cáceres-Guevara, Sarmiento and Cramer2013

Alispirifer cf. transversus; Pastor-Chacón et al., p. 20, pl. II, fig. k.

Holotype

Internal mold of a ventral valve from the Branch Creek Formation, Baywulla Station, Monto District, Queensland, Australia (Maxwell, Reference Maxwell1964, pl. 5, fig. 33).

Occurrence

Interval API-5, Ixtaltepec Formation, Arroyo las Pulgas; Bashkirian (Lower Pennsylvanian).

Description

Small and biconvex shell, extremely transverse with with a length-width proportion of ~1:3; cardinal extremities alate and acute; commissure uniplicate; shells up to 11.8 mm in length and 44.8 mm in width; ventral valve with interarea moderately high, ~2 mm, denticulate, and apsacline; delthyrium with ~ 55° angle, and an apical callus; small and gently curved beak; shallow, smooth, and well-delimited sulcus, originating at the beak; shell ornamented by rounded plications, with slightly angular interspaces, displaying 8–9 plications on each lateral flank, slightly indistinct on the cardinal extremities; small growth-lamellae abundant; interior with short and divergent dental adminicula; muscle field rhomboidal; dorsal valve with fold gently high; and ornamentation similar to the opposite valve.

Materials

An internal and external mold of an articulated specimen (FCMP 1544), two ventral valves (FCMP 1545, 1546), and an external mold of dorsal valve (FCMP 1547).

Remarks

Alispirifer transversus occurs in the Lanipustula Zone, which corresponds to the upper Serpukhovian–Moscovian (Upper Mississippian–Middle Pennsylvanian) (Taboada and Shi, Reference Taboada and Shi2011; Cisterna and Sterren, Reference Cisterna and Sterren2016). The species had only been reported in Australia (Maxwell, Reference Maxwell1964; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Hunt and Thompson1976), Argentina (Cisterna, Reference Cisterna1997; Cisterna and Sterren, Reference Cisterna and Sterren2016; Angiolini et al., Reference Angiolini, Cisterna, Mottequin, Shen, Muttoni, Lucas, Schneider, Wang and Nikolaeva2021), and Colombia (Angiolini et al., Reference Angiolini, Racheboeuf, Villarroel and Concha2003; Pastor-Chacón et al., Reference Pastor-Chacón, Reyes-Abril, Cáceres-Guevara, Sarmiento and Cramer2013).

Order Spiriferinida Ivanova, Reference Ivanova1972

Suborder Spiriferinidina Ivanova, Reference Ivanova1972

Superfamily Pennospiriferinoidea Dagys, Reference Dagys1972

Family Spiriferellinidae Ivanova, Reference Ivanova1972

Genus Spiriferellina Frederiks, Reference Frederiks1924

Type species

Terebratulites cristatus von Schlotheim, Reference von Schlotheim1816, by subsequent designation of Frederiks (Reference Frederiks1924); upper Permian (Thuringia, Germany).

Spiriferellina campestris (White, Reference White1874)

Figure 6.24–6.26

- Reference White1874

Spiriferina spinosa var. campestris White, p. 21.

- Reference White and Wheeler1877

Spiriferina octoplicata White, p. 139, pl. 10, fig. 8a (not 8b, c).

- Reference Mather1915

Spiriferina campestris; Mather, p. 193, pl. 13, figs. 9, 10.

- Reference Morgan1924

Spiriferina campestris; Morgan, pl. 45, fig. 7, 7a.

- Reference Sutherland and Harlow1973

Spiriferellina campestris; Sutherland and Harlow, p. 87, pl. 18, figs. 1–4.

Holotype

An articulated specimen from a locality near Santa Fe, New Mexico, United States (White, Reference White and Wheeler1877, pl. 10, fig. 8a).

Occurrence

Intervals API-5, API-6, and API-7, Ixtaltepec Formation, Arroyo las Pulgas. Bashkirian–Moscovian (Lower–Middle Pennsylvanian).

Description

Medium-sized, biconvex, transverse, and strongly punctate shell; cardinal extremities slightly extended; shells up to 14.9 mm in length and 28.4 mm in width; commissure uniplicate; ventral valve with interarea high, apsacline; sulcus angular, well delimited by a pair of rounded plications, gently broad; 5–6 thinner plications on lateral flanks; microornamentation of imbricate, thin, and closely spaced lamellae; interior with median septum moderately high, measuring one-third of the total length; dental adminicula short; dorsal valve with fold gently high, composed of a median plication distinctly higher at the anterior margin than the lateral ones; six plications on lateral flanks, and interarea orthocline.

Materials

Two internal molds of ventral valves (FCMP 1548, 1549), an external mold of a ventral valve (FCMP 1550), and an internal mold of a dorsal valve (FCMP 1551).

Remarks

The specimens display the traits mentioned by Sutherland and Harlow (Reference Sutherland and Harlow1973, p. 87) for the species, based on the lectotype of S. campestris described by White (Reference White and Wheeler1877). This species was also recorded by Beus and Lane (Reference Beus and Lane1969) from the Moscovian of the Ely Limestone of Nevada; however, their identification was based on Girty's (Reference Girty1903) material, which is a different taxon than Spiriferina campestris (Sutherland and Harlow, Reference Sutherland and Harlow1973). The samples of “S. campestris” from Nevada (Beus and Lane, Reference Beus and Lane1969, p. 997, 998, pl. 119, figs. 4, 8.) differ from our material in their more transverse shape and bigger size, as well as the arrangement and greater number of plications on both valves. In addition to this material, >20 specimens represent both valves in the collection.

Discussion

Stratigraphy and age

The Ixtaltepec Formation is divided into eight informal intervals (API-1 to API-8), each characterized by its fossil association (Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat, Reference Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat1997, Reference Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat1998). This stratigraphical distribution of the biota has allowed identification of the approximate depositional ages of the informal intervals, with brachiopods being the more useful proxy. This is the case for the rhynchonellid and spire-bearing brachiopods herein described, which are present in the distinct levels of the formation. Thus, we observed in the interval API-1 the presence of Anthracospirifer occiduus; in API-2 Allorhynchus scientiana n. sp., A. occiduus, and the indeterminate martiniid; and in API-3 Leiorhynchoidea sp. and Alispirifer tamaulipensis. Next, in API-5, we found A. occiduus, Anthracospirifer cf. A. “opimus”, Alispirifer transversus, and Spiriferellina campestris. In API-6, we found A. occiduus, Anthracospirifer newberryi, and S. campestris. In API-7, we found Leiorhynchoidea perrilliatae n. sp., Composita ovata, Huestedia rotunda, Crurithyris expansa, Anthracospirifer oaxacaensis n. sp., Anthracospirifer sp., and S. campestris, whereas in level API-8 we found only A. oaxacaensis n. sp.

Of these taxa, A. occiduus represents one of the most relevant, particularly given its currently recognized stratigraphic range. When Pantoja-Alor (Reference Pantoja-Alor1970) described the Ixtaltepec Formation, he assigned an age of Middle–Upper Pennsylvanian employing the occurrence of this species throughout the unit. At that time, A. occiduus was known as a Moscovian index fossil (e.g., Dunbar and Condra, Reference Dunbar and Condra1932; Hoare, Reference Hoare1961; B.O. Lane, Reference Lane1962; N.G. Lane, Reference Lane1963, Reference Lane1964; Sturgeon and Hoare, Reference Sturgeon and Hoare1968), making the age unquestionable. Later, given the relative age inferred by this brachiopod, along with the presence of some Pennsylvanian bivalves (Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat, Reference Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat1997, Reference Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat1998), the Ixtaltepec Formation rocks were assigned to Bashkirian–Moscovian (Lower–Middle Pennsylvanian), maintaining these stratigraphical stages for many years, until the brachiopods were carefully studied. Although A. occiduus has been widely recorded in the United States, in Mexico it has only been reported twice: (1) in the Bashkirian (Lower Pennsylvanian) of the La Joya Formation of Sonora (Jiménez-López et al., Reference Jiménez-López, Sour-Tovar, Buitrón-Sánchez and Palafox-Reyes2018), a Mississippian–Pennsylvanian unit (Navas-Parejo et al., Reference Navas-Parejo, Palafox, Villanueva, Buitrón-Sánchez and Valencia-Moreno2017); and (2) in most fossiliferous levels of the Ixtaltepec Formation, with lower and upper Carboniferous strata. Although most records of A. occiduus belong to the Bashkirian–Moscovian, its potential occurrence in Serpukhovian (Upper Mississippian) rocks of North America (e.g., Anthracospirifer cf. A. occiduus in Butts, Reference Butts2007) has raised controversy about whether this taxon is really a Lower–Middle Pennsylvanian index fossil.

Thus, the presence of brachiopods such as Orbiculoidea caneyana (Serpukhovian), Semicostella sp. (Serpukhovian), Productus concinnus (Visean–Bashkirian), Keokukia sp. (Visean), Inflatia inflata (Serpukhovian), Echinoconchella elegans (Serpukhovian–Bashkirian), Stegacanthia bowsheri (Serpukhovian), Marginovatia minor (Serpukhovian), Ovatia muralis (Serpukhovian), Undaria manxensis? (Serpukhovian), Sinuatella sp. (Visean–Serpukhovian), and Alispirifer tamaulipensis (Tournaisian–Serpukhovian) in the intervals API-1 to API-3 has allowed assignment of lower strata of the formation to the Serpukhovian (=Chesterian) (Upper Mississippian), despite A. occiduus occurring in levels API-1 and API-2. As for interval API-4, there are only ichnofossils and a few remains of plants; hence its age is still uncertain, although it is considered as the Mississippian-Pennsylvanian transition (Hernández-Ocaña and Quiroz-Barroso, Reference Hernández-Ocaña and Quiroz-Barroso2018). Interval API-5 can be correlated with the Bashkirian (=Morrowan) by the presence of Orbiculoidea capuliformis (Bashkirian–Moscovian), Anthracospirifer cf. A. “opimus” (Bashkirian–Moscovian), Neospirifer dunbari (Bashkirian–Gzhelian), and especially Echinoconchella elegans (Serpukhovian–Bashkirian) and Spiriferellina campestris (Bashkirian), as well as Alispirifer transversus, which is a typical species from the Lanipustula Zone of the late Serpukhovian–Moscovian (Upper Mississippian–Middle ennsylvanian) (Taboada and Shi, Reference Taboada and Shi2011; Cisterna and Sterren, Reference Cisterna and Sterren2016). The next interval (API-6) was related to the upper Bashkirian (=upper Morrowan–lower Atokan) because of the occurrence of Spiriferellina campestris (Bashkirian), but especially by the record of Anthracospirifer newberryi, which is an index fossil from the upper Bashkirian of the United States (Sutherland and Harlow, Reference Sutherland and Harlow1973; Gordon, Reference Gordon and McKee1982). Finally, the intervals API-7 and API-8 have been dated as Moscovian (=upper Atokan–Desmoinesian) mainly by the presence of Orbiculoidea missouriensis (Pennsylvanian–middle Permian), Reticulatia huecoensis (Pennsylvanian–lower Permian), Buxtonia websteri (Moscovian), Echinaria knighti (Moscovian), Linoproductus prattenianus (Moscovian–Gzhelian), Hustedia rotunda (Moscovian), and Crurithyris expansa (Moscovian–Gzhelian).

Paleogeographical significance

As the supercontinent Rodinia fragmented during the Proterozoic, the microcontinent Oaxaquia (currently, part of Oaxaca, Hidalgo, and Tamaulipas territories) separated from the Grenvillean belt, migrating and joining Gondwana during the Cambrian–Ordovician (Ortega-Gutiérrez et al., Reference Ortega-Gutiérrez, Ruíz and Centeno-García1995). During the Devonian, Oaxaquia detached from Gondwana and moved until it collided with Euramerica, completing the union of both continental masses at the beginning of the Carboniferous (Ortega-Gutiérrez et al., Reference Ortega-Gutiérrez, Ruíz and Centeno-García1995; Centeno-García, Reference Centeno-García2005). During the Mississippian, Euramerica began to move towards Gondwana, and the Rheic Ocean was reduced to a narrow sea between the western edge of Gondwana and the southwestern edge of Euramerican. Additionally, the Paleotethys remained surrounded to the west by Euramerica and Gondwana, while to the east it continued to be restricted by the smaller islands of China (McNamara, Reference McNamara and Burnie2009). During the Late Mississippian (Serpukhovian), the Rheic Ocean was still open as a narrow passage between continental masses, allowing interchange of marine currents from the east to the west side. At the end of the Serpukhovian and during the Bashkirian, Euramerica and Gondwana were completely merged, interrupting flow of the Rheic Ocean, which caused an alteration of ocean currents and the dispersal pattern of marine fauna (Groves and Yue, Reference Groves and Yue2009; Qiao and Shen, Reference Qiao and Shen2013). During the Early Pennsylvanian (late Bashkirian–Moscovian), as a result of the Rheic Ocean closure, the circum-equatorial current from east to west was redirected to the north and south of the supercontinent that was forming, along the west coast of the Paleotethys. This event forced displacement of warm equatorial waters towards high and cold latitudes (Smith and Read, Reference Smith and Read2000; Qiao and Shen, Reference Qiao and Shen2013).

In this paleogeographic context, deposition of the Carboniferous units found at Santiago Ixtaltepec occurred south of Oaxaquia, which was located in southwestern Euramerica at paleolatitudes close to Ecuador. During the Carboniferous, the Nochixtlán area was subjected to different geological processes, mainly resulting from the merger of Euramerica and Gondwana on their way towards the formation of Pangea. This process triggered numerous environmental variations observed throughout the Carboniferous succession, with environments related to reef, tidal plain (within the intertidal zone), shallow subtidal, peri-reef, and offshore observed within the continental platform (Torres-Martínez, Reference Torres-Martínez2014; Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2016b; Hernández-Ocaña and Quiroz-Barroso, Reference Hernández-Ocaña and Quiroz-Barroso2018). Such environmental modifications affected the distribution of the marine invertebrate associations from the region, especially influencing those composed of brachiopods.

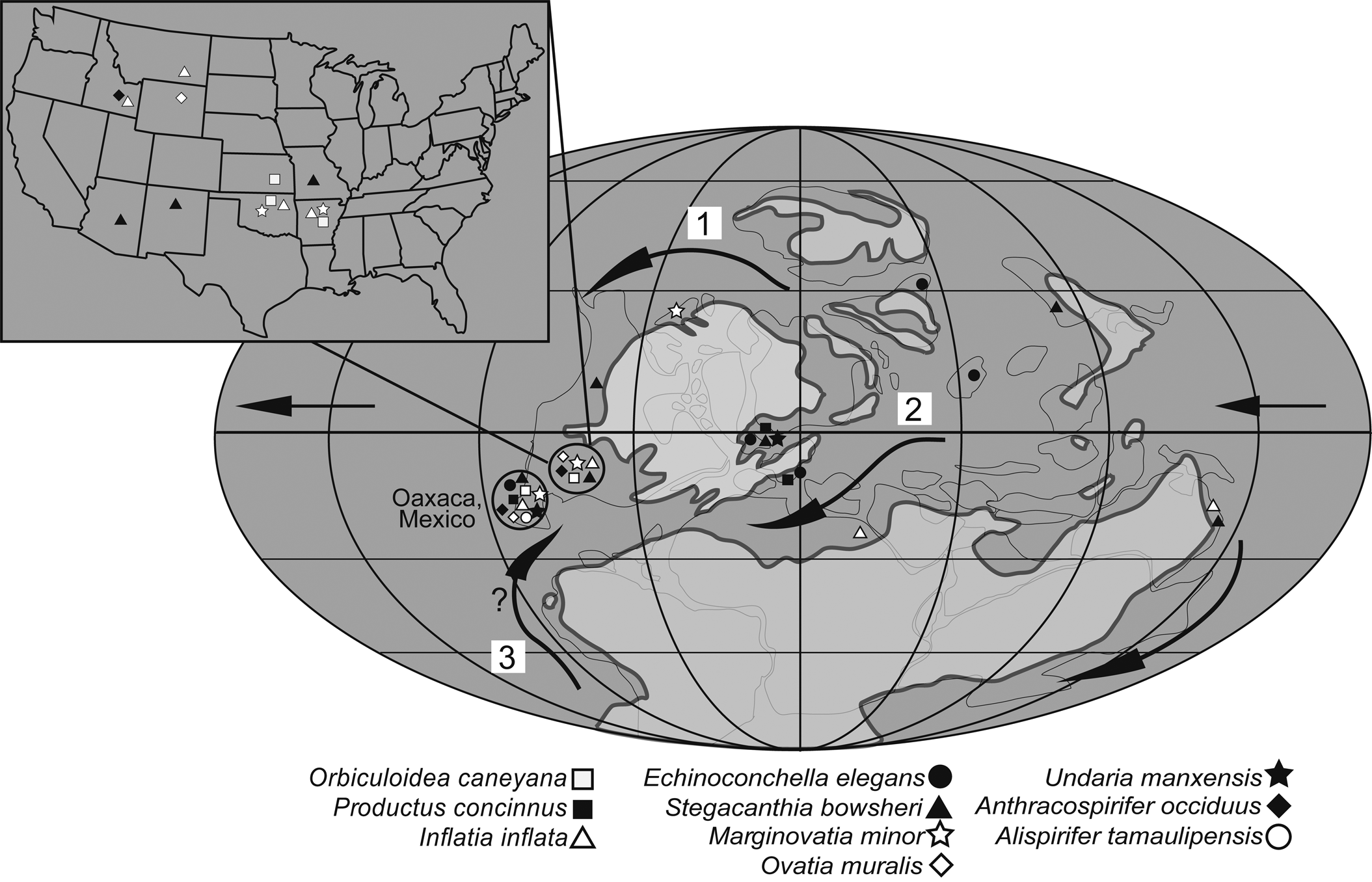

Because of this, variations of taxonomic associations through the Carboniferous succession provide significant information about the paleogeographic events that occurred at the end of the Mississippian and during the Early Pennsylvanian. Thus, we see that numerous taxa located in the intervals API-1 to API-3 displayed a cosmopolitan distribution at both the specific and generic level (Table 4), with stratigraphical distributions mainly confined to the Serpukhovian (Late Mississippian). This dispersal can be correlated with the presence of the circum-equatorial current that flowed continuously through the Panthalassa Ocean, Paleotethys, and the Rheic Ocean, allowing colonization of several brachiopod species in very disjointed geographical areas. According to Waterhouse (Reference Waterhouse1973), a determinant factor for this distribution is that brachiopods are very sensitive to extreme temperature variations and inhabit areas geographically separated with similar latitudinal ranges (Qiao and Shen, Reference Qiao and Shen2013). This proposal coincides with the pattern of distribution of the Mississippian Oaxacan brachiopods, which mostly display a migration pathway within tropical paleolatitudes, even if the regions were very distant from each other (e.g., Productus concinnus, Marginovatia minor, Inflatia inflata, Echinoconchella elegans, Undaria manxensis?, and Stegacanthia bowsheri) (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Reference map of the Serpukhovian, showing the geographical distribution of the Late Mississippian brachiopods from the Ixtaltepec Formation. Numbers indicate oceanic corridors: 1) Franklinian; 2) Rheic ocean; 3) Austropanthalassic-Rheic. The map includes a close-up of the current territory of the United States, displaying the location of brachiopods related to the Oaxacan unit.

Table 4. Previous records of species reported from Serpukhovian (Upper Mississippian) units of the Ixtaltepec Formation.

Inflatia inflata and S. bowsheri have been recorded in Mexico and Australia, which were extremely separated areas during the Serpukhovian. To explain the occurrence of the same taxon in both regions, Taboada (Reference Taboada2010) noted that the location of the Austropanthalassic-Rheic corridor could have favored the dispersion of many species along the south Polar circle. However, there are no reports of similar species to Serpukhovian Oaxacan taxa in the south Polar circle, suggesting that Mexican brachiopods did not use such a connection during the Late Mississippian. If this is true, the migration pathway of I. inflata and S. bowsheri could have been related to the equatorial current of the Tropical circles instead of the austral corridor.

The interval API-4 contains only ichnofossils and fossil plants associated with interference ripples and flaser-like stratification. This suggests a shallow stage during the Mississippian-Pennsylvanian transition (Hernández-Ocaña and Quiroz-Barroso, Reference Hernández-Ocaña and Quiroz-Barroso2018), possibly coinciding with closure interval of the Rheic Ocean.

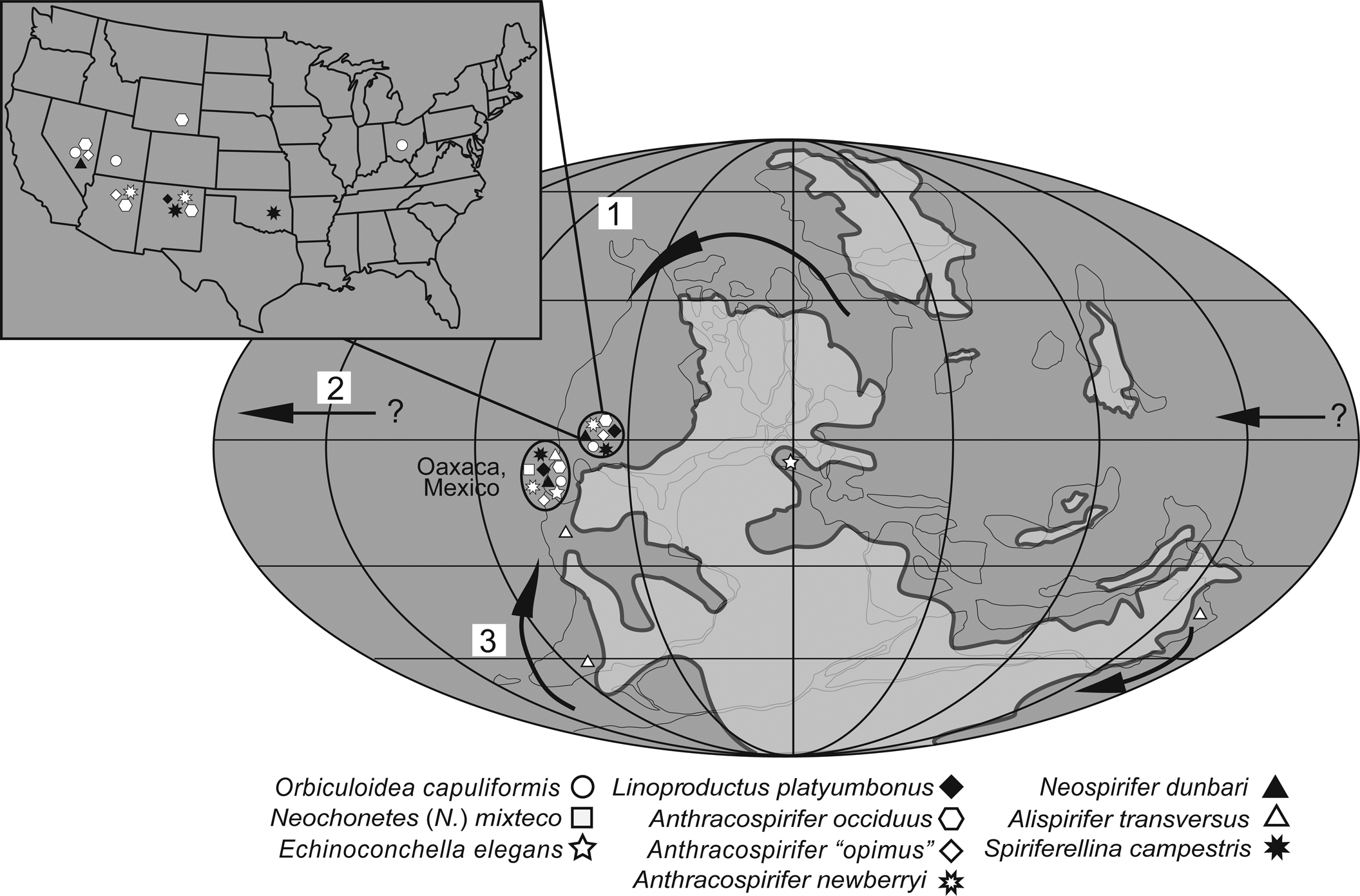

In the case of the brachiopod fauna from the Bashkirian (Lower Pennsylvanian) of the Ixtaltepec Formation (intervals API-5 and API-6), we observed a significant taxonomic provincialism in the west side of the continent (Table 5). Although the fauna shows low diversity, it is evident that the cosmopolitan nature of most species diminishes (Fig. 8). Nonetheless, the presence of Alispirifer transversus in Oaxaca, the distribution of which (Australia, Colombia, Argentina, and Mexico) certainly coincides with the Austropanthalassic-Rheic corridor, favors the exchange of cool- to cold-water tolerant brachiopods between southwestern and eastern Gondwana at the beginning of the Pennsylvanian. The presence of A. transversus in Santiago Ixtaltepec corroborates that this species not only reached localities within tropical latitudes of southwestern Gondwana (e.g., Colombia), but also equatorial zones (e.g., Oaxaca, Mexico). Regarding Echinoconchella elegans, it is not possible to corroborate if the taxon could have migrated between Mexico and Spain during the Bashkirian due to the lack of a fossil record. Because the species shows a similar stratigraphic range (Serpukhovian–Bashkirian) in both countries (Winkler Prins, Reference Winkler Prins and Renema2007; Martínez-Chacón and Winkler Prins, Reference Martínez-Chacón and Winkler Prins2009; Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2012), it can be suggested that E. elegans only endured in both paleoequatorial regions until the Early Pennsylvanian.

Figure 8. Reference map of the Bashkirian with the geographical distribution of the Early Pennsylvanian species from the Ixtaltepec Formation. Numbers indicate oceanic corridors: 1) Franklinian; 2) Equatorial; 3) Austropanthalassic-Rheic. The map includes a close-up of the current territory of the United States, displaying the location of brachiopods related to the Oaxacan unit.

Table 5. Previous reports of the Bashkirian (Lower Pennsylvanian) species of the Ixtaltepec Formation.

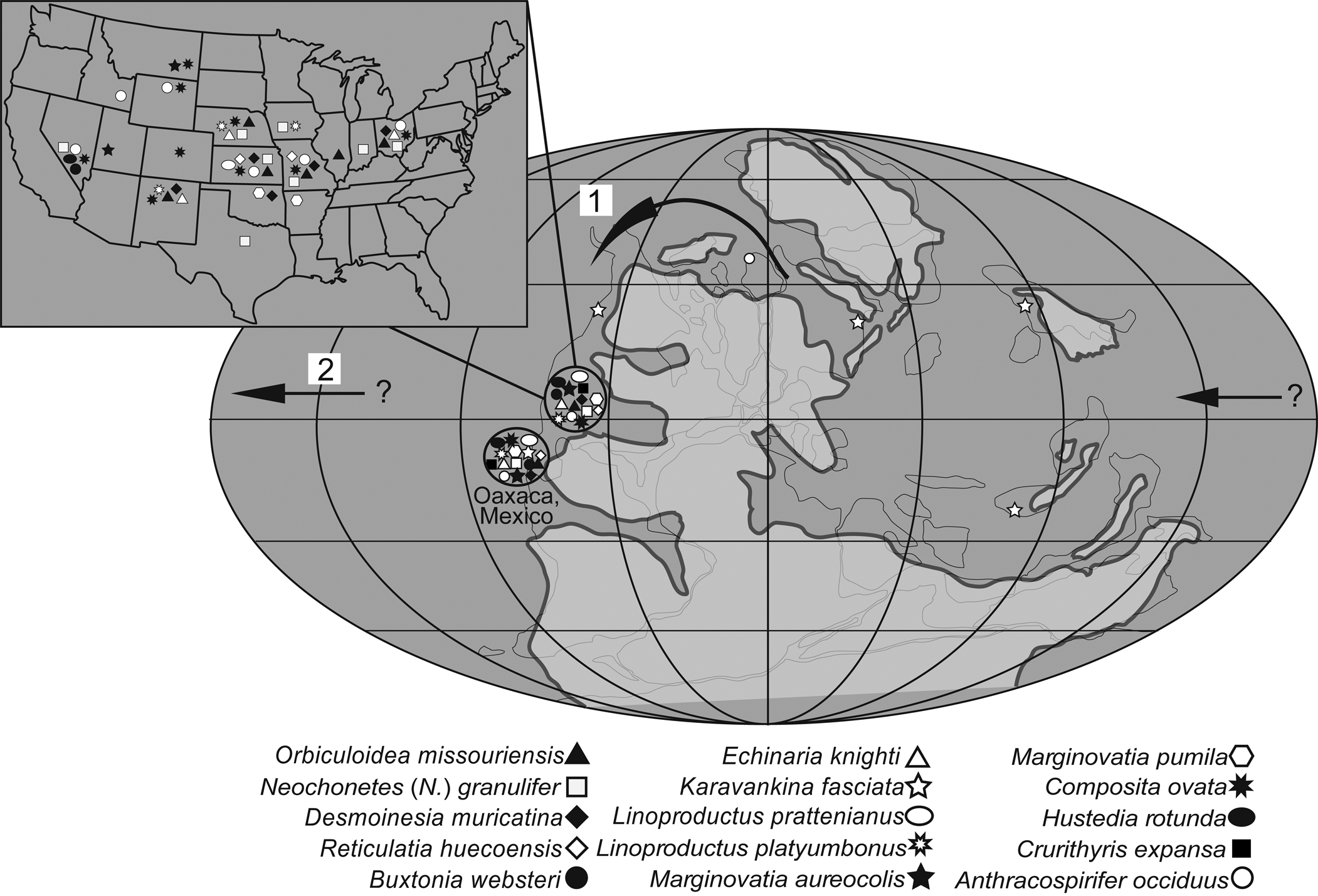

For the Ixtaltepec Formation Moscovian rocks, we found a greater number of exclusively North American taxa whose species were previously recorded in Missouri, Illinois, Nebraska, Wyoming, Arkansas, Montana, Kansas, Ohio, New Mexico, Utah, Oklahoma, Colorado, Texas, Idaho, Nevada, and Iowa in the United States (Table 6). This suggests that stronger taxonomic provincialism (Mexico-USA) occurred in the Middle Pennsylvanian, indicating a possible direct marine connection between the shallow waters of Oaxaca and the Mid-Continent epicontinental sea of the United States (Missouri, Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico) (Sour-Tovar, Reference Sour-Tovar1994; Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat, Reference Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat1997; Torres-Martínez et al., Reference Torres-Martínez, Sour-Tovar and Pérez-Huerta2008, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2018; Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2012, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovar2016a, Reference Torres-Martínez and Sour-Tovarb). There also may have been a link with the Great Basin (Nevada, Utah), the Illinois Basin (Illinois, Indiana), the Appalachian Basin (Ohio), and the Alliance Basin (Wyoming, Idaho, Montana) seas (see Algeo and Heckel, Reference Algeo and Heckel2008, p. 207, fig. 2). This coincides with the results of Porras-López (Reference Porras-López2017), highlighting that the main affinity between taxa from Mexico and the United States occurred until the Pennsylvanian and not the Mississippian, as had been noted previously (Fig. 9).