Introduction

Increasingly, citizens perceive a democratic deficit: a gap between the democratic ideal of power to the people, and the democratic practice of representative democracy (Norris, Reference Norris2011). Populism is thought to thrive where the experienced gap between democratic ideal and democratic practice becomes too wide (Canovan, Reference Canovan1999). Indeed, research has shown that citizens with high populist attitudes are particularly aware of and sensitive to the democratic deficit (Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert, Reference Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert2020). Could their sensitivity to the democratic deficit mean that they are likewise particularly sensitive to efforts to close the gap between the democratic ideal and democratic practice?

One such effort could be the implementation of democratic innovations, which have been put forward as a way of bringing democratic principle and practice closer together, particularly those innovations that focus on increasing citizens’ say in political decision-making (e.g., Smith, Reference Smith2009; Geissel and Newton, Reference Geissel and Newton2012; Elstub and Escobar, Reference Elstub and Escobar2019). A participatory budget (PB) is one such democratic innovation that gives a high amount of decision-making power to participating citizens.

Several theorists claim that PBs have a positive effect on participants’ political attitudes (Elstub and Escobar, Reference Elstub and Escobar2019; Wampler et al., Reference Wampler and Wampler2021). PBs have, under the right circumstances, indeed been found to increase respect, as well as the perceived responsiveness of the political elite (Coleman and Sampaio, Reference Coleman and Sampaio2017; Swaner, Reference Swaner2017; Volodin, Reference Volodin2019). However, no research has analyzed the effect of participation in a PB on populist attitudes.

This paper thus seeks to answer the following two questions: To what extent does participation in a PB have an effect on populist attitudes? Are citizens with high populist attitudes affected differently than citizens with low populist attitudes? There are strong theoretical reasons to expect that citizens with high populist attitudes are particularly likely to be affected by participation in a PB, since PBs respond to the populist demand for more popular control by giving citizens direct decision-making power and a chance to interact with political elites.

We assessed these expectations with the use of panel data from four PBs in the Netherlands. We first compared the average level of populist attitudes after the PB with the baseline level. We then conducted a difference-in-differences analysis to detect different effects for citizens with high populist attitudes as compared to citizens with low populist attitudes.

We find that participation in a PB does not lead to an overall significant change in populist attitudes among participants. However, we do find a different effect for participants with high populist attitudes as compared to participants with low populist attitudes. Participants who hold higher populist attitudes experience a significant decrease in populist attitudes, while for participants with low populist attitudes we observe no significant change. The difference in change between these groups, moreover, proves to be significant.

This paper contributes to existing literature in several ways. First, it focuses on the effect of participation in a PB rather than support for a PB, thus moving away from the hypothetical relationship between populism and citizen participation to the actual effects of participation. Second, it examines the effects of a heretofore under-researched type of participatory process, of which the effect on participants has been tested empirically to a very limited extent (Theuwis et al., Reference Theuwis2021).

In the following section, we describe populist attitudes and the particularities of citizens with high populist attitudes. We subsequently summarize what is known about the transformative potential of PB. We then explain why we expect participation in a PB to have a diminishing effect on populist attitudes, especially in citizens with high populist attitudes. In the method section, we outline our research design, before presenting and reflecting upon the results of our study.

Theory and literature

Populist attitudes

This section describes populist attitudes and the features of citizens with high populist attitudes. We first briefly define the term populism, we then explain how populism manifests itself in individuals in the form of populist attitudes, and, finally, we describe the characteristics shared by citizens with high populist attitudes.

This paper defines populism using the ‘ideational approach’, which conceives of populism as a set of ideas (e.g., Mudde, Reference Mudde2004; Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart, Reference Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart2016), rather than conceiving of it as, among others, a discourse (e.g., De Cleen and Stavrakakis, Reference De Cleen and Stavrakakis2017), a strategy (e.g., Weyland, Reference Weyland and Kaltwasser2017) or a political logic (Laclau, Reference Laclau2005). The ideational approach ‘considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite,” and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people’ (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004: 543). In addition, populism is considered to be a ‘thin’ ideology, because it merely provides a way of making sense of the public sphere rather than a full-fledged vision of that public sphere (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2017: 7).

The ideational approach manifests as a political ideology among parties and as an attitudinal syndrome at the citizen level. A review of theoretical works on populist ideology among parties shows that in essence, populist ideology consists of three sub-dimensions: people-centrism or a celebration of the people (e.g., Canovan, Reference Canovan1999; Taggart, Reference Taggart2000; Stanley, Reference Stanley2008); anti-elitism or an opposition to the corrupt elite who ignore the general will (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004; Müller, Reference Müller2014); and Manichaeism or the perception of moral antagonism between the good people and the corrupt elite (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004; Stanley, Reference Stanley2008).

People-centrism, anti-elitism and Manichaeism in isolation are not unique to populist ideology. Therefore, party scholars have come to agree that in order to qualify as adhering to populist ideology, all three subdimensions should be present (Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2019). In addition, and importantly, the three populist subdimensions are considered strongly interrelated (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2017).Footnote 1

Relatively recently, populism scholars have begun studying populism at the individual level.Footnote 2 Populist individuals are thought to have higher levels of ‘populist attitudes’ (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins2012; Akkerman and Mudde, Reference Akkerman and Mudde2014; Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva2018; Schulz et al., Reference Schulz2018; Wuttke et al., Reference Wuttke2020). A conceptualization of populist attitudes ultimately depends on a scholar’s ontological approach (considering populism as a set of ideas, a strategy or a discourse).

Castanho Silva and colleagues (Reference Castanho Silva2020) have reviewed different types of operationalizations of populist attitudes and show that they either reflect the unidimensionality of populism and interrelatedness of subdimensions that is inherent to the ideational approach (e.g., Akkerman and Mudde, Reference Akkerman and Mudde2014); or consider populism to consist of separate and independent subdimensions, which more closely adheres to the discursive approach (e.g., Schulz et al., Reference Schulz2018). Since we follow the ideational approach to populism, we will operationalize populism through the populist attitudes scale developed by Akkerman and colleagues (2014). This scale is particularly suited to our conception of populist ideology since it explicitly takes into account the interrelatedness of populism’s subdimensions.

To have higher levels of populist attitudes thus means that one sees politics and society through a populist ‘lens’, in terms of a Manichean struggle between the good people and the corrupt, unresponsive elite, that is unable or unwilling to heed the general will of the people (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2017). Importantly though, holding populist attitudes does not automatically translate to populist voting behavior (Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert, Reference Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert2020). Conversely, the characteristics that describe the average populist voter do not automatically apply to the average person holding higher populist attitudes. Thus, while it has been found that the average populist voter is likely to be lower-educated, lower-income, young, White, and male (e.g., Kriesi, Reference Kriesi and Grande2008), these characteristics do not necessarily describe citizens with high populist attitudes. What we do know about citizens with higher populist attitudes is that they are more likely to be ‘losers of globalization’, even though this sociodemographic profile only applies to Western Europe and is not found among South-American citizens (Spruyt et al., Reference Spruyt2016; Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel, Reference Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel2018; Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert, Reference Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert2020).

Moreover, all citizens with populist attitudes share an extraordinary democratic profile. Citizens with high populist attitudes are thought to see themselves as ‘true democrats’ (Canovan, Reference Canovan1999: 2; Mény and Surel, Reference Mény, Surel, Mény and Surel2002). Empirically, they exhibit this by showing a special sensitivity to the gap between the democratic ideal (power to the people) and the democratic practice (electoral democracy). Citizens with high populist attitudes, in particular, have a strong belief in the democratic ideal and are greatly disappointed with how that ideal works in practice. In other words, they are ‘dissatisfied democrats’ (Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert, Reference Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert2020: 7). This at least means they share a rejection of representative or ‘trusteeship’ democracy (Heinisch and Wegscheider, Reference Heinisch and Wegscheider2020; Zaslove and Meijers, Reference Zaslove and Meijers2021). Whether this also translates into support for more direct forms of democracy, that puts the power back in the hands of the people, is less clear. Heinisch and Wegscheider (Reference Heinisch and Wegscheider2020) found no evidence of this. However, other research does suggest that citizens with high populist attitudes support forms of citizen participation, both referendums (Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs2018; Mohrenberg et al., Reference Mohrenberg2019; Zaslove et al., Reference Zaslove2020) and deliberative mini-publics (Zaslove et al., Reference Zaslove2020).

The relationship between populism and democracy is further highlighted by the fact that populist attitudes become salient (i.e., they translate into actual populist voting behavior) when political elites are perceived to be (extremely) corrupt or unresponsive (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins2020). We thus argue that populism in individuals must first and foremost be seen in connection to a perceived democratic deficit.

Participatory budgeting

Democratic innovations are ‘[p]rocesses or institutions that are new to a policy issue, policy role, or level of governance, and developed to reimagine and deepen the role of citizens in governance processes by increasing opportunities for participation, deliberation and influence’ (Elstub and Escobar, Reference Elstub and Escobar2019: 14). In doing so, democratic innovations aim to enhance the democratic goods that are potentially lacking in representative democracy (Smith, Reference Smith2009).

Generally, democratic innovations are designed with deliberative and direct democratic theory in mind. Deliberative theory posits that ‘the public deliberation of free and equal citizens is the core of legitimate political decision-making and self-government’ (Bohman, Reference Bohman1998: 401). Deliberative democratic innovations such as mini-publics exist of a group of randomly selected citizens that deliberate about a policy advice. Deliberative democratic innovations thereby enhance the democratic good of considered judgment (Smith, Reference Smith2009). Direct democratic theory is based on the idea of ‘popular sovereignty as a way of addressing the demands of citizens and the dependence of public policies on their preferences’ (Altman, Reference Altman2010: 1). Direct democratic innovations, such as referendums, entail that all citizens get to directly decide on policy-making though voting. As such, direct democratic innovations increase the democratic good of popular control (Smith, Reference Smith2009).

Participatory budgeting is a type of democratic innovation that takes elements from both deliberative as well as direct democratic theory. From deliberative theory it takes the element of deliberation about a policy. From direct democratic theory, it takes the element of voting. As such, PBs allow citizens to participate in the distribution of public finance through a process of deliberation and voting (Wampler, Reference Wampler2000; Sintomer et al., Reference Sintomer2008; Elstub and Escobar, Reference Elstub and Escobar2019).Footnote 3

Participatory budgets (PBs) originated in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in 1989 as a component of a progressive leftist initiative aimed at promoting greater social equity and strengthening community influence (Zamboni, Reference Zamboni2007; Baiocchi and Ganuza, Reference Baiocchi and Ganuza2014). As they gained popularity globally in the 2000s, they underwent a transformation, evolving into a mechanism for fostering innovative governance rather than primarily serving the purpose of advancing social justice (Baiocchi and Ganuza, Reference Baiocchi and Ganuza2014).

It has been claimed that PBs contribute to better governance, increase government accountability and thereby reduce corruption. They are also said to engage the disengaged voter (Zamboni, Reference Zamboni2007). However, PBs have also been criticized on many fronts. Participating citizens are often unrepresentative, and they do not necessarily lead to the most efficient policy decisions. The budget devoted to the PB by governments is often only a small part of the total budget. Therefore, some scholars have claimed that PBs are used by local governments as a ploy to keep citizens busy while the government can divvy up the rest of the budget (Godwin, Reference Godwin2018).

Yet, the emphasis on popular control continues to be an important element of PBs (Smith, Reference Smith2009: 39–55; Baiocchi and Ganuza, Reference Baiocchi and Ganuza2014: 32). All the four cases in our study apply a model of PB that can be described in Sintomer and colleagues’ (Reference Sintomer2008) terms as ‘Porto Alegre adapted for Europe’. Central to this model is that citizens have de-facto decision-making power about the allocation of part of the local budget. The discussions are an important aspect of the process and take place in groups. This model of PB has been adopted in many other cities in Europe which enhances the external validity of this study. In particular, the cases in our study apply a form of PB that has first been employed in the Belgian city of Antwerp since 2014, which we will describe in more detail in the method section (Renson, Reference Renson2020).

Hence, the level of popular control and policy impact of the PBs in this study is higher as compared to deliberative instruments (Smith, Reference Smith2009; Michels, Reference Michels2011; Elstub and Escobar, Reference Elstub and Escobar2019), while the degree of contact and exchange with authorities is greater as compared to direct instruments. These aspects of popular control and contact with authorities are, as we argue in the subsequent paragraph, substantial for the impact of participation on citizens’ populist attitudes. That is why we consider PBs to be a most-likely case to have an effect on populist attitudes.

Theorizing the effect of participation in a PB on populist attitudes

Could participation in PBs have an effect on populist attitudes? Several scholars have claimed that such participation has a positive effect on the relationship between citizens and authorities, and that participants’ perceptions of political actors become more positive after participation (Sintomer et al., Reference Sintomer2008; Wampler et al., Reference Wampler and Wampler2021). Empirical research regarding PB’s effect on political attitudes, however, is limited. Although a growing body of research has shown a strong positive relationship between populist attitudes and support for direct or deliberative democracy (e.g., Zaslove et al., Reference Zaslove2020), no theorizing nor empirical research regarding the extent to which participation in a PB affects these attitudes has been done. That is why we theorize in the second part of this section to what extent participation in a PB affects populist attitudes.

Several scholars have claimed that PB events potentially transform how citizens interact with the political system, and, in doing so, deepen democracy (e.g., Wampler, Reference Wampler2010). PBs contribute to better communication between citizens, civil servants, and local politicians (Sintomer et al., Reference Sintomer2008) and, as a result, they counter political disaffection in Western democracies (Elstub and Escobar, Reference Elstub and Escobar2019: 78). Additionally, PBs function as ‘schools of democracy’ (Pateman, Reference Pateman1970). Citizens have a direct experience in policy-making processes and therefore change their attitudes toward local governments (Wampler et al., Reference Wampler and Wampler2021).

Empirically, participatory experiments have found some positive effects on participants’ political attitudes, such as their social trust and satisfaction with democracy (Grönlund et al., Reference Grönlund2010; Setälä et al., Reference Setälä2010; Strandberg and Grönlund, Reference Strandberg and Grönlund2012). Additionally, studies into deliberative mini-publics, during which citizens often have direct contact with authorities and exchange views with fellow citizens, showed some positive effects on external political efficacy, that is, the belief that the government is responsive to one’s demands (Curato and Niemeyer, Reference Curato and Niemeyer2013; Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2019; Munno and Nabatchi, Reference Munno and Nabatchi2020), and political trust (Tomkins et al., Reference Tomkins2010; Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2019; Weymouth et al., Reference Weymouth2020).

With regards to actual PBs, the bulk of empirical research uses qualitative data, while quantitative measurements are scarce. Based on interviews, Coleman and Sampaio (Reference Coleman and Sampaio2017) found that online participation leads to increased feelings of external efficacy, but only if the outcome of the PB was implemented. Researchers at a New York PB interviewed participants and found that participation leads to a greater level of respect for local council members. However, unresponsive communication from the part of the organizing authorities leads to a decrease in trust of those unelected local authorities (Swaner, Reference Swaner2017). Volodin (Reference Volodin2019) statistically assessed the effect of participation in a field PB on political trust. He found that, on average, levels of trust in local political actors, such as the mayor and the city council, increased among participants. Hence, PB processes that have a direct impact on policy-making, which is often the case in the Dutch context (Michels et al., Reference Michels2018), can thus serve as a cue to participants that local authorities are willing to listen to them and subsequently enhance their satisfaction with those authorities.

Having described general explanations for the effects that participating in a PB can have on political attitudes, this next paragraph outlines to what extent we can expect participation in a PB to have an effect on populist attitudes in particular.

Studies suggest a fairly strong correlation between populist attitudes, on the one hand, and political trust and perceptions of elite responsiveness, on the other (Geurkink et al., Reference Geurkink2020). Since PBs have been shown to increase political trust and external efficacy, we expect that participation in a PB will have a diminishing effect on populist attitudes:

HYPOTHESIS 1: Participation in a PB decreases populist attitudes.

In what follows we explain why we expect this effect to be particularly strong for citizens with high populist attitudes. As explained above, higher populist attitudes are expressions of populist ideology in citizens, that is, these citizens see the public sphere through a populist ‘lens’. Therefore we expect that the experience of a PB of citizens with higher populist attitudes is primarily colored by their populist ideology. We furthermore expect that the above described effect of participating in a PB on populist attitudes on citizens with higher populist attitudes is even stronger, because the particular features of PB are so well suited to address the democratic grievances inherent in populist ideology.

Firstly, one of the most important features of the ‘Porto Alegre adapted for Europe’ type of PB is the fact that participating citizens are given a large amount of decision-making power: they get to determine a (small) part of public spending. The experience of being given decision-making power and seeing that their decision is implemented could not only increase external political efficacy (Coleman and Sampaio, Reference Coleman and Sampaio2017), but also decrease the belief that the elite is unresponsive to the demands of the people. On the other hand, if citizens are disappointed with the amount of decision-making power they get or the authorities do not actually implement (adequately) the citizens’ policies, this might backfire and populist sentiments could attenuate (Spada and Ryan, Reference Spada and Ryan2017). When PBs act as emasculated decision-making venues (Wampler, Reference Wampler2010), the democratic good of popular control could be further limited and populist sentiments could rise.Footnote 4

Additionally, the act of making decisions and learning about the work of public authorities could increase understanding for and empathy with elites (Swaner, Reference Swaner2017; Wampler et al., Reference Wampler and Wampler2021). An enhanced understanding of the complexity of policy-making might counter the expectation of policy-making as simply the execution of the popular will. When citizens with high populist attitudes experience that the popular will is not completely homogenous and that citizens hold different justifiable policy opinions, they might abandon the idea that the elite is not responsive to a unitary popular will.

What is more, research into the effects of participatory processes has consistently shown that the perception of being treated respectfully by governmental actors has beneficial effects on citizens’ attitudes toward the authorities (Hartz-Karp et al., Reference Hartz-Karp2010; Swaner, Reference Swaner2017). Citizens with high populist attitudes’ belief in the ‘elite’ as evil and corrupt makes them especially sensitive to elite behavior. We expect that they are likely to take notice if the elite treats citizens with respect, and that this experience will improve their perceptions of the elite. However, when the elite’s behavior is disrespectful, citizens with high populist attitudes would notice as well. When, for instance, they do not communicate responsively with citizens or are not transparent about their involvement in the PB, this could enhance the already existing mistrust (Swaner, Reference Swaner2017).

Finally, during a PB, citizens usually develop plans for public spending through discussion or deliberation among each other, making it a highly people-centrist form of participatory decision-making (Zaslove et al., Reference Zaslove2020). We expect that participation in a PB will support citizens with high populist attitudes in their belief that the people are wise and capable of generating solutions to difficult problems, and subsequently in their idea that the people, rather than the elite, should be the main source of legitimate decision-making power.

Moreover, populist ideology conceives of the elite (and the people) as a homogeneous group. Populists can dislike local politicians, national ones or even economic, cultural and media elites and, as Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2017) put it succinctly, ‘[a]ll of these are portrayed as one homogenous corrupt group that works against “the general will” of the people.’ (p. 12). Hence, we expect that citizens with high populist attitudes classify any politician they encounter as part of that homogenous ‘elite’ group. There are therefore theoretical reasons to expect that a positive or negative experience with a local politician (and that politicians’ responsiveness to the people’s will) ‘spills over’ to the general assessment of ‘the elite’ (and their responsiveness).

Thus, we expect that the populist attitudes of citizens with higher populist attitudes will be especially affected by participation in a PB. We therefore formulate the following hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 2: Participation in a PB more strongly decreases the populist attitudes of participants with higher populist attitudes as compared to participants with lower populist attitudes.

Methods

The hypotheses will be tested with the use of panel data from four PB events. Before and after each event, populist attitudes were measured. In the first part of this section, the case selection is described. In the second part, the measurement of populist attitudes is explained in detail. In the final part, the methods of analysis are elaborated.

Case selection

To assess the effect of participation in a PB on populist attitudes, this paper uses panel data from four PBs in the Netherlands which took place in Duiven, Maastricht, and Amsterdam-East (Old-East and IJburg).

The Netherlands was selected as it constitutes a typical European case (Gerring, Reference Gerring2008). Dutch citizens consistently hold populist attitudes comparable to other Western industrial democracies (Akkerman et al., 2014; Zaslove et al., Reference Zaslove2020). Additionally, the Netherlands have populist parties at both the left and the right, which means that the populist thin-centered ideology is present in the public sphere across the political spectrum (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman2017).

Duiven, Maastricht, and Amsterdam-East were selected as they provide a different context to test the hypothesized effect. The variable on which we based our selection was the degree of urbanization. Duiven is a small town with an address densityFootnote 5 of 1,160 (StatLine - Regionale kerncijfers Nederland, 2022). Maastricht is a medium-sized city with an address density of 2,520. Amsterdam-East is part of a large city and has an address density of 4,155. The higher the address density, the higher the degree of urbanization. The degree of urbanization matters because it could affect the proximity of local authorities to citizens. This could, in turn, affect citizens’ previous experiences with these authorities and therefore have an impact on the effect of participation in a PB. By choosing cases that differ in their degree of urbanization, the effect of participation can be tested across these differing contexts.

All four cases apply the Antwerp model of PB. Apart from the typical characteristics of PB like the combination of discussion and voting regarding public spending, similar to most other PBs, the Antwerp model is characterized by the self-selection of participants and the direct authority of decisions. All inhabitants are invited to take part in the decision-making process through various channels.Footnote 6 This self-selection process often results in the ‘usual suspects’ turning up.Footnote 7 In three rounds, citizens decide how to divide the local budget between projects. The first round focuses on discussion: participants pick five themes which they personally consider important. In the second round, the budget is divided between the chosen themes through discussions in combination with a final vote. Subsequently, citizens are free to propose projects related to the themes and they can check the viability of their projects with civil servants. In the final round, citizens in the area can vote (online) for their favorite projects. The selected projects are announced at a ‘festival’ (Sobol, Reference Sobol2021).Footnote 8

At least two researchers were present to observe the process of each PB event. The proceedings were described and extra attention was devoted to possible deviations from the Antwerp model of PB and incidents that could affect our findings. For instance, the PB of Duiven entailed cutting the budget by €10,000 and allocating €20,000 on projects.Footnote 9 The last round of the PB in Amsterdam IJburg was moved online due to the COVID − 19 pandemic soaring during the PB. The pandemic also affected the length of some PBs: the PB of Amsterdam IJburg and the PB of Maastricht lasted for several months, whereas the other PBs only lasted several weeks. As a robustness check we assessed how these between-case differences affected our findings in ‘Testing the robustness of the estimated effect’. This check yielded no case-specific effects.

Measuring populist attitudes

We measured populist attitudes before and after participation in a PB through surveys that contained the populist attitudes scale of Akkerman and colleagues (2014). The surveys were filled out by participants just before the first round and right after the second round of the PB.Footnote 10 The third round was not included in the treatment as for some cases this round did not take place in person, while for others it did. This decision was made in order to keep the cases comparable and the treatment consistent. The scale developed by Akkerman and colleagues (2014) was opted for as a measurement of populist attitudes as it has a high level of internal coherence and external validity (Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva2020). The populist attitudes scale consists of six items that together tap into some of the core dimensions of populism discussed earlier: Manichaeism, anti-elitism, and popular sovereignty. The higher a person scores on this attitude scale, the more this person perceives politics and society through a populist ‘lens’.

The items included in the populist attitudes scale are the following:

-

1) The politicians in the Dutch parliament need to follow the will of the people.

-

2) The political differences between the elite and the people are larger than the differences among the people.

-

3) The people, and not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions.

-

4) I would rather be represented by a citizen than by a specialized politician.

-

5) Elected officials talk too much and take too little action.

-

6) What people call ‘compromise’ in politics is really just selling out on one’s principles.

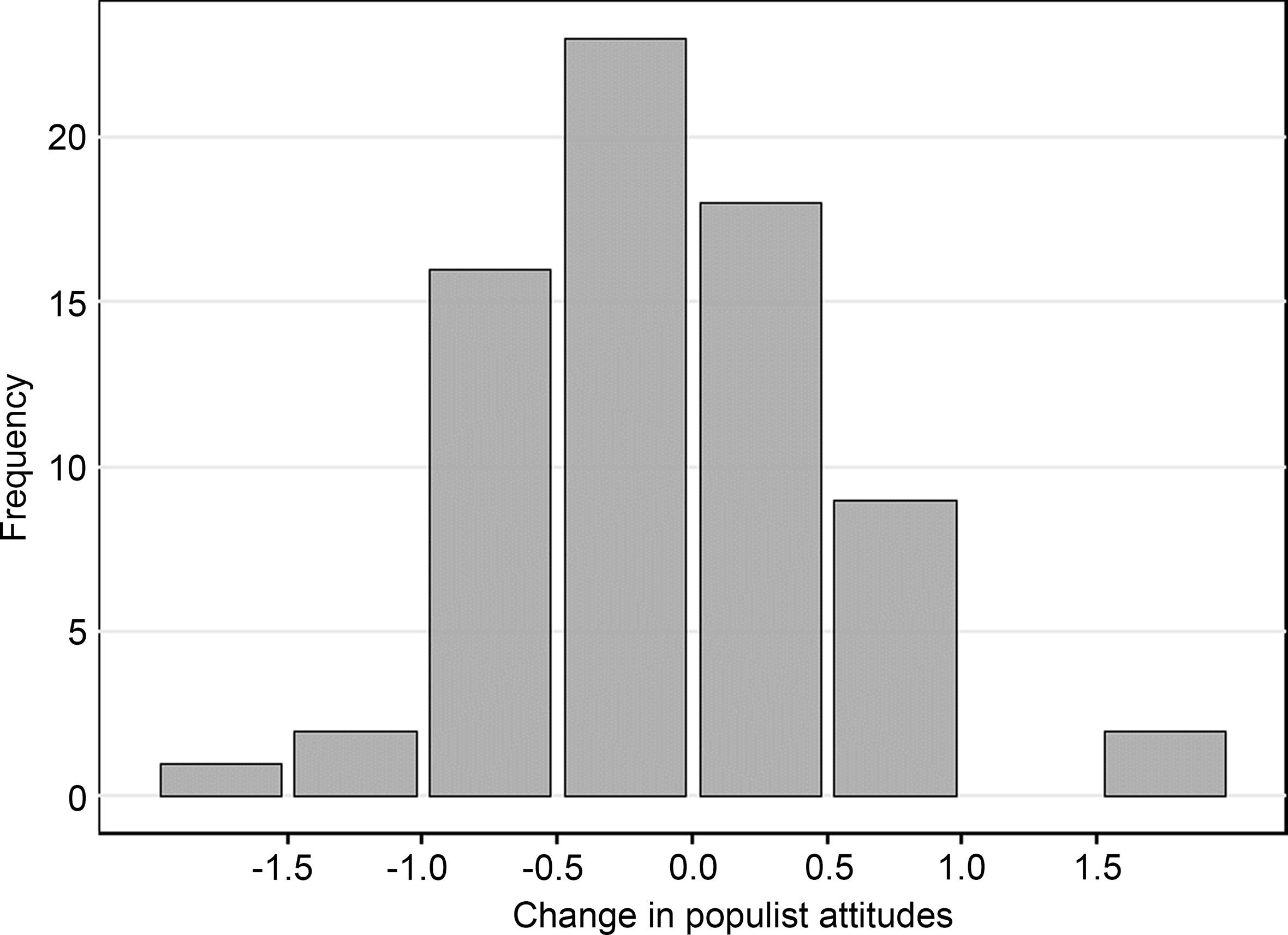

For each statement, respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement on a scale of 1 (fully disagree) to 5 (fully agree). The average value across the six items is what we will refer to as a respondent’s populist attitudes, which can range from 1 to 5. A respondent’s populist attitudes were measured twice: right before and immediately after participation in the PB. The difference between these two measurement is our main analysis’ dependent variable and measures a respondent’s change in populist attitudes, which can range from −4 to 4. In Fig. 1 a distribution of this variable is shown.

Figure 1. Histogram of the variable ‘change in populist attitudes’.

In order to differentiate between citizens with high and low populist attitudes, we chose to uphold a cutoff point of 3.5, meaning that citizens with high populist attitudes have an average level of populist attitudes of 3.5 or higher, whereas citizens with low populist attitudes have an average level of populist attitudes below 3.5. This cutoff point was adopted as it lies above the middle and covers approximately the upper quartile of our sample. Nevertheless, as a robustness check, we verified whether our findings hold for different cutoff points (see ‘Effect of participation on citizens with high populist attitudes’).

Methods of analysis

In order to test the first hypothesis, we assessed the change in populist attitudes before and after participating in the PB. We did so via a paired samples t-test which allows us to examine within-unit change over time. To test the second hypothesis, we looked at whether there is a different effect from participation for citizens with high populist attitudes as compared to citizens with low populist attitudes. A suitable method to assess between-groups effects over time is a difference-in-differences analysis (Angrist and Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2008). We checked its robustness with a regression analysis that controls for demographics and the case fixed effect. Additionally, we conducted further robustness checks to account for outliers, ceiling effects, and regression to the mean, which are common issues that can bias the estimated effect (cf. online Appendix E).

Results

Descriptive statistics

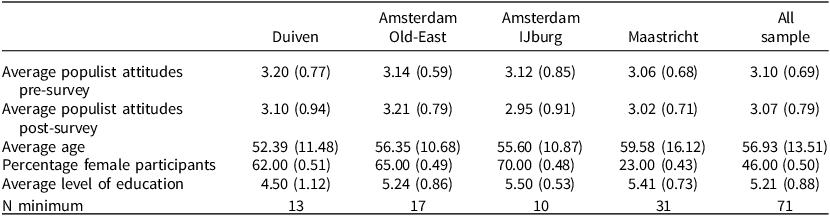

From the descriptive statistics in Table 1 we observe that overall, populist attitudes on average slightly decrease after participation. This can equally be observed for all but one of the four individual cases. In the rest of this section we assess whether this decrease is significant and whether the demographics and individual cases affect the overall effect. It is important to note that our sample is older, more educated, and more politically interested than the general Dutch population (see also online Appendix C). However, the population that we research consists of citizens who would participate in a ‘Porto Alegre adapted to Europe’ model of PB, not of the entire Dutch population.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for participants who filled out both the pre-survey and post-survey

Note. Standard deviations are displayed in parentheses. Average level of education: 1=primary education; 2=lower secondary education; 3=higher secondary education; 4=vocational training; 5=university college education; 6=university education. Descriptive statistics for all participants who filled out at least one survey can be found in online Appendix C.

Effect of participation on populist attitudes

The results of our first hypothesis test are presented in Table 2.Footnote 11 They show that participants’ populist attitudes decreased by 0.03 on average. This decrease is however not significant at any standard level of significance. Therefore, we fail to confirm our first hypothesis as we found no evidence that participation in a PB leads to a decrease in citizens’ populist attitudes.

Table 2. T-Test of change in populist attitudes for all participants

Note. Standard errors are displayed in parentheses. Paired t-test with one-tailed significance levels.

*P < 0.1, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01.

Effect of participation on citizens with high populist attitudes

In order to test the second hypothesis, we compared the average change in populist attitudes between citizens with high and low populist attitudes.Footnote 12

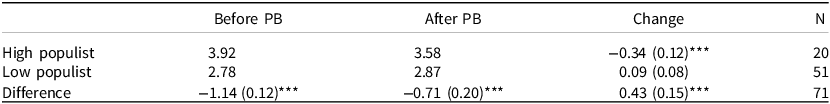

Figure 2 visually shows that the populist attitudes of these two groups were affected differently by their participation in a PB: the populist attitudes of citizens with high populist attitudes decreased, whereas the populist attitudes of citizens with low populist attitudes increased. In Table 3 we assess the significance of these between-group differences. Most importantly, it shows that, even though the sample of citizens with higher populist attitudes is small, participation in a PB significantly decreased their populist attitudes. The increase in populist attitudes among citizens with lower populist attitudes is not significant. The difference-in-differences estimator, moreover, shows that the difference in effect of participation in a PB on populist attitudes among citizens with higher and lower populist attitudes is significant. The populist attitudes of citizens with high populist attitudes decreased by 0.34 points, which is significantly different from the increase of 0.09 points experienced by citizens with low populist attitudes. Thus, we find evidence to partially support our second hypothesis: the populist attitudes of participants with higher populist attitudes decreased more than the populist attitudes of participants with lower populist attitudes. However, before accepting hypothesis 2, we conducted several robustness checks.

Figure 2. Plot change in populist attitudes for citizens with high and citizens with low populist attitudes.

Table 3. Difference-in-Differences analysis: difference in change in populist attitudes between citizens with high and citizens with low populist attitudes

Note. Standard errors are displayed in parentheses. High populist (average populist attitudes pre >= 3.5); low populist (average populist attitudes pre < 3.5). Bootstrapped paired samples one-tailed t-tests were conducted to assess changes over time. Bootstrapped unpaired samples one-tailed t-tests were conducted to assess differences between the groups. The difference between these statistics is the bootstrapped difference-in-differences estimator.

*P < 0.1, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01.

Testing the robustness of the estimated effect

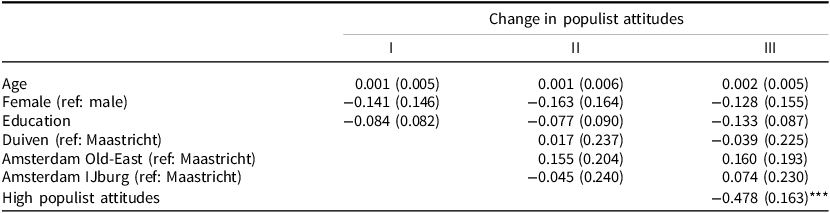

Individual-level and contextual factors, rather than the treatment and initial populist attitudes, could also account for the effect we observed. To test whether that is the case, we conducted a regression analysis that includes several demographic variables as well as case dummy variables.Footnote 13

Model II, as displayed in Table 4, shows that none of these variables can explain the main effect of participation on all participants. Even though there were some differences in the context and design of the cases, these differences do not affect the change in populist attitudes among participants. Moreover, Model III in the same table shows that holding high populist attitudes significantly predicts the decrease in populist attitudes, even after controlling for demographic and case variables. We checked whether, as theorized, satisfaction with the PB event moderated the effect, which was not the case (see online Appendix E.5).

Table 4. Regression models of change in populist attitudes including demographic and case variables

Note. Regression coefficients are unstandardized and shown with standard errors in parentheses. Models are linear regressions where the dependent variable is the change in populist attitudes (−4; 4) from before to after the PB. Education (1=primary education; 2=lower secondary education; 3=higher secondary education; 4=vocational training; 5=university college education; 6=university education); High populist attitudes (1=average populist attitudes pre >= 3.5; 0=average populist attitudes pre < 3.5). Maastricht was chosen as a reference category because it is a medium-sized city, whereas the other cases are either a small town or a large city.

*P < 0.1, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01.

As mentioned earlier, we could have opted for other cutoff points than 3.5 to split our sample into citizens with high and low populist attitudes. Therefore we re-ran our analysis with other cutoff points, of which the results can be found in online Appendix E.1. The direction of change for both groups remains the same, even though the difference in a change becomes insignificant. This is likely due to the small sample size of the group of citizens with high populist attitudes, which means that our study is limited in exploring the effect of different cutoff points.

Another factor which could bias our estimates is regression to the mean. As we split our sample into two groups for testing the second hypothesis, the effect we find might be generated by the fact that observations at the margin of the cutoff point could be misclassified due to the realization of their errors. In order to check whether our analysis is affected by regression to the mean, we repeated the analysis of Table 4 but replaced the dummy variable of high populist attitudes with a continuous variable. The results can be found in Table 13 in online Appendix E.2. We see that the variable of interest, that is, the populist attitudes before the PB, still significantly explains a decrease in populist attitudes, while control variables still fail to account for that effect. We thus find no evidence for the influence of regression to the mean on our estimates.

We further conducted an outlier analysis via a Grubb’s test of the highest and lowest value of our dependent variable ‘populist attitudes change’ (see online Appendix E.3). The test showed that there are no outliers in our dataset.

A last factor that could bias our findings are ceiling effects. Ceiling effects mean that the scale on which we measure populist attitudes artificially limits the change that participants can experience because change is only possible from −4 to 4. However, our robustness check (see online Appendix E.4) showed that ceiling effects did not significantly influence our findings.

Conclusion

We did not find evidence to support the claim that participation in a PB has a significant effect on the populist attitudes of all citizens. Nevertheless, when looking at the effect of participation for citizens with high populist attitudes only, we see that they significantly decrease their attitudes after participation. Moreover, even after controlling for case effects, citizens with high populist attitudes are significantly differently affected by participation as compared to citizens with low populist attitudes.

These findings constitute evidence that PBs are successful at bringing the democratic ideals of citizens with high populist attitudes into practice. For citizens with low populist attitudes, PBs do not seem to have any substantial effect. Having contact with local authorities and being able to directly decide on public spending thus seems to affect those citizens that are most disillusioned with democracy. The transformative experience of participating in a PB for these citizens is like stepping through the looking glass.

Our study had several limitations. First, due to the relatively small sample size, we might not have had enough statistical power to detect an effect of participation on all participants. With regard to the different effect of citizens with high and low populist attitudes, however, the small sample size did not seem to affect our findings as small samples generally lead to type II errors (false negatives). Despite this small N, we did find a significant difference between citizens with high and low populist attitudes. Nevertheless, it would be useful to assess whether this finding also replicates in different settings with larger samples.

Furthermore, research in a different country-setting would strengthen our findings. We designed our research in a way that the size of the polity was different, while attempting to keep other factors, such as the PB process and the country, constant. The fact that all cases took place in the Netherlands limits their generalizability to countries that, for instance, do not have a multi-party system with several populist parties.

Additionally, the four cases in this paper apply the ‘Porto Alegre adapted to Europe’ model of PB which entails that the outcome was binding. In other countries, different PB models that are merely consultative are more prominent. In Germany and France, for instance, PB processes entail ‘selective listening’ by the government (Sintomer et al., Reference Sintomer2008). In such cases we would expect no or even a negative effect on populist attitudes since the popular will is not executed. Therefore, our findings can only be generalized to countries that also apply the ‘Porto Alegre adapted to Europe’ model of PB and future research should assess the effect for other models of PB.

Furthermore, even though we do not aim to generalize beyond participants to ‘Porto Alegre adapted to Europe’ PBs, our sample is more politically interested, more highly educated and older than the Dutch population. On the one hand, this could entail that our sample is less likely to change their political attitudes, since their attitudes are more accessible and therefore more resistant to change (Bartle, Reference Bartle2000; Howe and Krosnick, Reference Howe and Krosnick2017). On the other hand, this could mean that our sample is more likely to change their attitudes, since more ‘politically aware’ citizens are better able to process input related to their attitudes (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). Future research could assess to what extent participants to democratic innovations are more or less likely to change their populist attitudes as compared to the general population.

We also only assessed short-term effects of participation, that is, we measured the effect immediately after the PB. It is possible that these effects are only momentary and that they might be reversed, maintained or even exacerbated depending on the policy uptake and possible further contact with the authorities (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2019). Therefore, subsequent studies should look at long-term effects in different policy uptake contexts.

In addition, this study conceived of populist attitudes as an attitudinal syndrome related to a unidimensional concept. However, we acknowledge that there are other approaches to populist attitudes that see the subdimensions of populism as more independent and subsequently allow for the study of populist subdimensions in isolation (i.e., Schulz et al., Reference Schulz2018). While this approach does not suit the conceptualization of populism taken in this paper, a study of the effects of participation in a PB on populist citizens from a different perspective on populism might consider to what extent participation in a PB affects individual subdimensions.

Relatedly, we operationalized populist attitudes as general political attitudes, thus not tailored specifically to the local level. We argue that, while attitudes in general are evaluations about objects that can strongly differentiate according to the level (i.e., trust in local politicians as opposed to national level politicians), populist attitudes are particular in their conception of their objects – the people and the elite – as homogeneous groups. Populist actors classify all members of elites into one homogenous corrupt group that works against ‘the general will’ of the people (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2017). Empirically, however, it might be that populist attitudes items that are tailored to the local level yield bigger effect sizes and lower p-values than found in this paper (cf. Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2019). To what extent this also holds true in actual empirical research is an important question for future research.

Lastly, we focused on the effect of participation in a PB on populist attitudes. Interestingly, small variations in context and design do not seem to affect our findings. Therefore, imperative to interpret and understand our findings is to study the causal mechanism that explains this effect. In order to understand why citizens with high populist attitudes are affected differently than citizens with low populist attitudes, research that focuses on experiences and perceptions during the PB that could account for such a differing effect would be highly beneficial. Such research could inform future designs of democratic innovations that bring the democratic ideals of those that are most disillusioned with democracy into practice.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773923000413.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Hans Asenbaum and Friedel Marquardt for their suggestions and Alex Lehr for his methodological insights. We would furthermore like to thank Kristof Jacobs for his feedback throughout the writing process. We would also like to thank the discussants and participants to the panel ‘The impact of democratic innovations on citizens’ democratic attitudes and process preferences’ of the ECPR General Conference 2022 and the panel ‘Democratic innovations and citizen participation’ of the NIG Conference 2022 for their feedback.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

An earlier version of this paper has appeared as a working paper in the Centre for Deliberative Democracy & Global Governance working paper series.